History Blog

|

|

|

|

|

In 2004 the Steamship Historical Society of America produced the documentary film, "Steamboats: On the Hudson." Featuring footage from rarely seen private collections and from public archives, including scenes of the famous Robert Fulton, the last Hudson steamboat powered by a walking-beam engine. Historian Roger Mabie of Port Ewen contributes his first-hand knowledge of Hudson River steamboat history, and noted steam expert Conrad Milster offers perspective on the machinery that drove the era. The film also features Hudson River Maritime Museum Curator Emerita, Allynne Lange. In April, 2020, the Steamship Historical Society of America shared this documentary film on their YouTube channel, which allows us to share it with you! For over 150 years steamboats ruled the Hudson River, carrying passengers and freight between Albany and New York, and the many river communities in between. This program looks back at the golden age of steam, when spit and polish, and elegant surroundings marked a style of travel that has now disappeared. The Hudson is where steam navigation began, and it is where the American river steamer reached its ultimate expression, with enormous paddle-wheeled vessels carrying over 5,000 passengers. Featuring still photographs, historic film footage, and interviews, "Steamboats: On the Hudson" documents the evolution of steam vessels on the Hudson, from the early 1800s up to the final trip of the steamer Alexander Hamilton in 1971. We hope you enjoy this engaging and informative documentary film. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

0 Comments

The shipbuilding industry that flourished in Athens and New Baltimore from the mid-19th century until the time of World War I has been overlooked for too long by historians. The small shipyards of these villages turned out many steamboats, steam lighters and barges, but arguably their lasting contribution to the maritime world was in the sizable fleets of tugs that came from local yards, which included Morton & Edmonds, Van Loon & Magee, Peter Magee, William D. Ford and R. Lenahan & Co. in Athens; and, in New Baltimore, J.R. and H.S. Baldwin, William H. Baldwin and that grandly-named-but-short-lived late-comer, the New Baltimore Shipbuilding and Repair Co. The vessels were built for the area’s two principal markets- Albany and New York City. In Albany, the eastern terminus of the Erie Canal, an impressive fleet of small harbor tugs performed two functions: They shepherded the multitude of canal boats that traversed the Erie Canal after they had reached Albany, and many of these tugs towed barges and canal boats on the canal itself. In New York - then, as now, one of the nation’s major ports - these tugs joined the workforce of commerce of that place, docking and undocking seagoing vessels, shifting barges among the multitude of piers, and performing many other tasks. The tugs built at Athens number over eighty, including the well-known side-wheel towboat Silas O. Pierce, launched by Morton & Edmunds in 1863. She eventually came under the ownership of Rondout-based Cornell Steamboat Company, as did a number of other Athens-built vessels, such as the Thomas Chubb of 1888, H.D. Mould of 1896, P. McCabe, Jr. (renamed W.B. McCulloch) of 1899, and Primrose of 1902. New Baltimore’s output of tugboats was around fifty vessels. This fleet was composed of some interesting vessels, such as the side-wheel towboats Jacob Leonard and George A. Hoyt in 1872 and 1873. Both were in the Cornell fleet. George A. Hoyt was the last side-wheel towboat constructed as such- - most vessels of the type having been converted from elderly passenger steamboats. Over the years, Cornell also acquired a number of New Baltimore propeller tugs, such as Jas. A. Morris of 1894, Wm. H. Baldwin of 1901, R.J. Foster of 1903, Robert A. Scott of 1904, and Walter B. Pollack (later renamed W.A. Kirk) of 1905. R.J. Foster and Robert A. Scott had originally towed ice barges for the Foster-Scott Ice Company. The last tug built at Athens was the diesel-propelled Thomas Minnock, built in 1923 by R. Lenahan for Ulster Davis. She lasted until the early 1960s, although many of her last years were in lay up at the Island Dock at Rondout while owned by the Callanan Road Improvement Company. New Baltimore’s last tug was Gowanus, built for the legendary Gowanus Towing Company by the Baldwin yard in 1921. In recognition of the shipbuilding prowess of the shipbuilders of Athens and New Baltimore, we of the Hudson River Maritime Museum tip our collective hats to the accomplishments of these accomplished artisans and mechanics. -by William duBarry Thomas AuthorThis article was originally written by William duBarry Thomas and published in the 2006 Pilot Log. Thank you to Hudson River Maritime Museum volunteer Adam Kaplan for transcribing the article. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

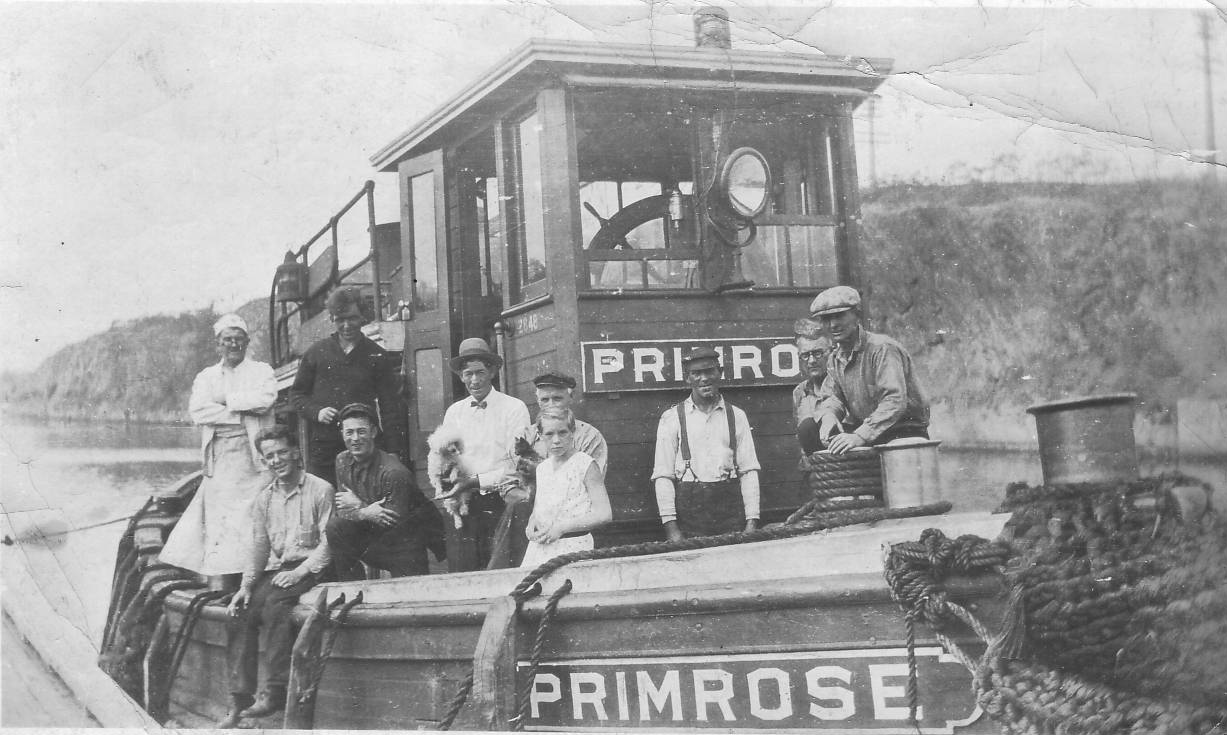

Editor’s Note: The following text is a verbatim transcription of an article featuring stories by Captain William O. Benson (1911-1986). Beginning in 1971, Benson, a retired tugboat captain, reminisced about his 40 years on the Hudson River in a regular column for the Kingston (NY) Freeman’s Sunday Tempo magazine. Captain Benson's articles were compiled and transcribed by HRMM volunteer Carl Mayer. See more of Captain Benson’s articles here. This article was originally published November 7, 1971.  Tugboat "Primrose" with crew on New York State Barge Canal in 1927. Here she is on the Barge Canal with her pilot house lowered to the main deck and smokestack cut down to permit passage under the canal's many low bridges. Look closely to see the poodle and cat eyeing each other warily. Hudson River Maritime Museum collection. Back in the 1920's, the Cornell Steamboat Company owned a tugboat that went by the flowery name of Primrose. For two long months at the time of which I write, the crew had been working and working hard without a day off. Tired of the continuous running, the men were beginning to complain among themselves. Some tugs that seemed to have "pull" with the dispatcher were getting a Sunday lay up, but not the Primrose. So the crew lodged a formal complaint with the office. The dispatcher seemed sympathetic. "Well," he said, "Sunday night I think the work will be caught up and you'll probably lay in to Monday night." Couldn't Be Spared But when Sunday came, he said they couldn't spare the tug and she'd have to work. The orders at that time were coming from Cornell's New York office at the old 53rd Street pier on the Hudson River. The crew didn't argue; just took the orders and picked up a loaded coal barge at the D. L. and W. R. R. coal trestle and took it to Staten Island. Once arrived, the captain had an idea. "Let's go to Newark," he said. "I know the channel and we can take a couple of days off. Let them find the tug themselves." So away they sailed to Newark, N.J. — taking Sunday night off. Business was so busy that weekend at Cornell, the office didn't even notice that the Primrose hadn't called in for orders yet — and here it was Monday afternoon. Police Scoured Harbor When the office finally awoke to the fact it had a missing tugboat, it had everybody at Cornell looking for her. Police boats scoured the harbor, and Cornell's own people looked high and low for the missing Primrose - but nobody could find her. Along about Tuesday afternoon, someone from Newark called the New York custom house. "There's a nice looking tugboat that's been tied up at our dock since Sunday night," he said, "and nobody s on her. She's all painted up, nice and clean, red with yellow panels, black stack, yellow umbrella, and white trim. Her name's Primrose and she's out of Rondout. Everything seems to be in order, but no steam on her and nobody aboard." The custom house put in a call to the Cornell office to ask if their tug Primrose was over at Newark. Cornell admitted she was the subject of a search; surmised as how the crew must have stolen her since the office had given no orders to go to Newark. Cornell's superintendent of operations, Robert Oliver, along with Terry Minor and Mr. Broad from the company's office, eventually arrived in Newark to find the tug all tied up shipshape, fires pulled, kitchen tidied up, but no crew. Home to Kingston Thundered Oliver: "I'll fire the whole clew from top to bottom!" Observed Broad: "How are you going to fire the crew when they ain't even here? That gang quit Sunday night and they're probably up in Kingston right now." And that's where they were, all right. After their night off on Sunday, they figured they might just as well go on home the following morning, since they hadn't been home for two months. They also figured Cornell would give them all another job anyway. They figured right but not completely. Eventually, Cornell hired all of them back again -- but never again was that same crew to be together on the same boat. The men were always kept separated on different tugboats. AuthorCaptain William Odell Benson was a life-long resident of Sleightsburgh, N.Y., where he was born on March 17, 1911, the son of the late Albert and Ida Olson Benson. He served as captain of Callanan Company tugs including Peter Callanan, and Callanan No. 1 and was an early member of the Hudson River Maritime Museum. He retained, and shared, lifelong memories of incidents and anecdotes along the Hudson River. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

|

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 info@hrmm.org Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |