History Blog

|

|

|

|

An Up-To-Date Ice Yacht Using A Sail Boat Rig by Raymond A. Ruge Yachting magazine December 193612/1/2023 Editor's Note: This article by Raymond A. Ruge is reproduced from the December 1936 issue of Yachting magazine. The language, spelling and grammar of the article reflects the time period when it was written. For information about current ice boating on the Hudson River go to White Wings and Black Ice here.

In spite of all the progress toward efficiency and speed made in sailing yachts, the ice boat, the fastest non-motorized vehicle known to man, has remained until very recently the slave of convention and tradition. Improvements in materials, sails, runners, rigging and construction details followed one another in steady progression, but in her fundamental design, the ice boat of 1930 was the ice boat of 1870 — and she still retained the devilish habit of spinning. There was no escaping the tendency to depress the bow and lift the stern whenever a hard puff struck the sails. This inevitable result of the action of the forces driving her is familiar to all small boat sailors. In a sail boat, with her rudder buried deep in the water, it is not particularly annoying. But let an ice boat's rudder be lifted the slightest fraction of an inch and it loses its already precarious grip on the glassy surface, and away she goes, in a cloud of ice slivers and a roar of grinding runners, around and around in a double or even triple spin, completely out of control. At a speed of sixty to seventy miles an hour, which is common enough, and with a competitor driving hard only a few feet astern, the possibility of a nasty crack-up is not hard to imagine.

Once the simplicity of this, and the beautiful self-compensating relation of wind pressure to rudder-on-ice pressure, dawns on you, it seems too good to be true. While it is difficult to assign the exact credit for this brilliant solution of the ice boat's one great fault, it is safe to attribute the development and perfection of the bow-steerer to the famous Meyer Brothers, of Wisconsin. They built and raced the renowned Paula series of ice yachts, all champions but all experimental, each one eliminating certain faults found in her predecessor. Editor’s Note: This article is found in "Time" magazine, Monday, Feb. 08, 1937 As a result, the bow-steerer is now as safe as she is fast, and ice yachting is coming into its own all over the northern part of the country. For the bow-steerer won't spin. Her pilot need not ease her through the puffs — he can hold his sheets and let her go — and the fact that bow-steerers everywhere are consistently defeating older boats of far greater sail area is sufficient proof that she can go. Convinced by the logic of this analysis of spinning, and of the bow-steerer as the solution, during the fall of 1925 I constructed Icicle. She carried the rig of my 18-foot one-design sail boat - about 190 square feet, in a conventional jib and mainsail. A club was added to the foot of the jib, both to keep it flat and to simplify the jib sheet. By using a club, a single sheet working on a traveler makes the jib practically self-tending, a necessary feature where the main sheet and steering wheel require constant attention. The rig of almost any small sloop can be used on an ice boat if provision is made for the heavier wind stresses involved. Wintry blasts are heavier, faster and harder-hitting than summer breezes. Sails which have been discarded because they have stretched and lost their precious draft are just the ones to use on your ice boat for, contrary to sail boat practice, the rule here is ”the flatter, the faster.” Icicle has a fuselage, or body, made of light frames and ribs, covered with unbleached muslin to which was applied airplane "dope™ and aluminum paint. This superstructure serves merely as a shield from the biting wind and is built around the traditional central backbone timber, made of an 18-foot 4" x 6" to which was bolted a 16-foot 4" × 4", over- hanging 6 feet aft. This composite timber rides on edge, with the 4" x6" below and toward the bow. The runner plank crosses under the extreme after end of the 18-foot lower member. The mast is stepped directly on the backbone, passing through a hole in the cloth deck which also admits the main and jib sheets to the cockpit, where they are controlled by jam cleats. The backbone also carries the steering gear and all fastenings for frame guys, so that the cloth super-structure is subjected to no stresses except those caused by wind pressure. This permits a comfortable, protected riding position, automobile steering, and a side-by-side arrangement of the two seats, all of which tend to increase the pleasure and reduce the discomfort of a day's fast sailing.

The runner plank shown embodies the latest improvements in design. First of all, those familiar with past practice will note the unusual length of the plank for the sail area carried. This serves two purposes; it prevents excessive hiking and makes for easy riding, both of which are aids to speed. By using waterproof casein glue, a laminated arched plank, light in weight and springy in action, is easy to make. The second departure from older practice lies in the extra foot of plank projecting beyond the runners. This carries on its underside a smooth, rounded oak sliding block which comes in contact with the ice when the boat hikes very high and allows her to slip sideways and come down right side up rather than capsize. A good runner plank is essentially a broad, flat wooden spring. A stiff plank means a slower boat. The runner plank is fastened to the backbone by two pieces of 2-1/2" x 2-1/2" angle iron, drilled for bolts through the side rails and plank. A block of rubber under the bearing surfaces will absorb some of the shock when passing over rough ice. The most vital parts of any ice boat, where the right thing is the only thing, are the runners. There are many types of runners in use, but the oldest is still one of the most satisfactory and may be sometimes acquired in good condition second, third, and even fourth-hand. This type of runner consists of an oak top piece to which is bolted a cast iron or steel shoe, sharpened to a "V" edge. It is in the subtle but all important rocker of the shoe and the correct angle of the ice faces, or the two sides of the "V," that the fast runner differs from the slow one. For an all-purpose runner, which will carry the boat through soft ice and slush as well as over hard, black ice, the faces of the shoe, called "ice faces." should meet at about 90° and be from ½" to ¾" wide. The rudder is a shorter edition of the main runners but has little rocker. The rudder must be kept sharp for, if it skids, control of the fast-moving craft is, at best, sketchy. After the runners are mounted, oil the inside faces of the chocks, next to the runners. This is one spot that must not be varnished or painted. Graphite is often smeared over these faces to help the runner rock freely. Keep the runner shoes greased to prevent rusting; when leaving the boat for a protracted interval, it is well to remove the runners entirely and keep them at home, along with the sails, where they will be dry and safe from inquisitive skaters. Allowing $40.00 for new runners, and the same amount for a fair suit of sails, the materials for this boat should total about $120. The yachtsman who has a sail boat with a suitable rig and the usual assortment of odd rigging, turnbuckles, blocks, etc., can cut the necessary outlay down to $75. Clear spruce is the lightest and best material for the spars, runner plank and back-bone; fir is second choice. Fir is easier to get and is cheaper but is apt to be heavy. Runner tops, chocks and knees are of quartered white oak. Plywood 3/8" thick is ideal for deck and bottom of back-bone. A few oak slats passing under the plywood floor from rail to rail will stiffen it sufficiently under the cockpit. A boat of this type can be transported easily by trailer, and two men can set her up in an hour, provided that this has been already completely done at home before taking the boat to the ice. It is hoped that the success of the adapted sail boat rig may encourage other yachtsmen to build ice boats to carry the rigs of their sail boats. The most active ice boating centers in the East are all within fifty miles of New York and can be reached by car in a couple of hours. I know I can speak for the ice boating fraternity in assuring all of you a most cordial welcome to this king of winter sports. Editor’s Note: During the fall of 1925, Ray Ruge, at age 17, constructed the Icicle. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

0 Comments

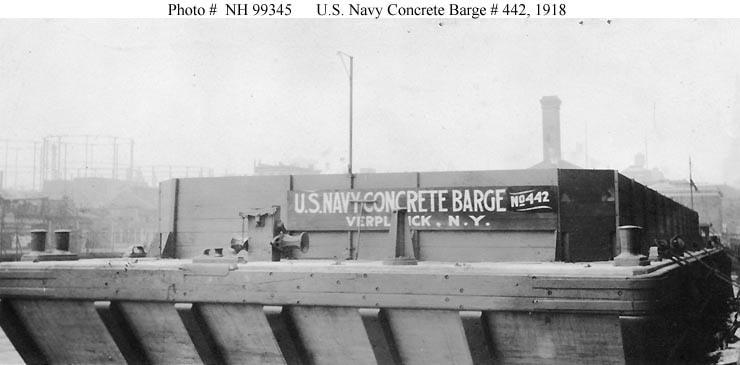

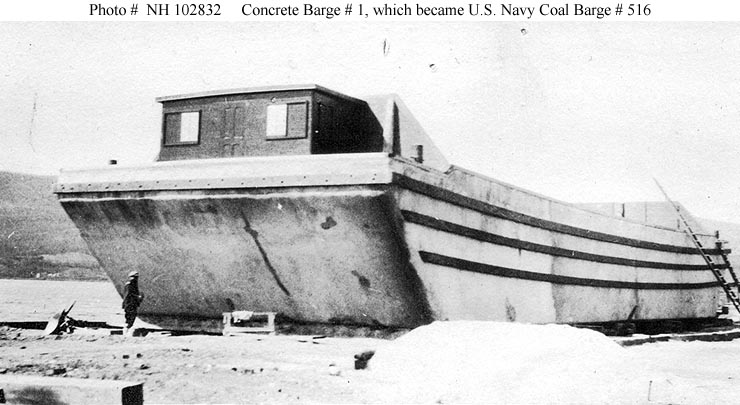

itle: Concrete Barge # 442 Description: (U.S. Navy Barge, 1918) In port, probably at the time she was inspected by the Third Naval District on 4 December 1918. Built by Louis L. Brown at Verplank, New York, this barge was built for the Navy and became Coal Barge # 442, later being renamed YC-442. She was stricken from the Navy Register on 11 September 1923, after having been lost by sinking. U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph. Hiding away in Rondout Creek, New York at 41.91245, -73.98639 is the last known surviving example of a World War I Navy ‘Oil & Coal’ Barge. It is less than a kilometer up the Rondout Creek from the Hudson River Maritime Museum. Based on a lot of ‘Googling’, it seems probable this is the first time that the provenance and history of this particular relic of concrete shipbuilding in the United States during the World War I era has been recognized. [Editor's Note: The concrete barge is featured on the Solaris tours of Rondout Creek.] The hulk is, in fact, the initial prototype of a ‘Navy Department Coal Barge’, concrete barges that were commissioned by the Navy Department : Bureau of Construction and Repair. This was the department of the U.S. Navy that was responsible for supervising the design, construction, conversion, procurement, maintenance, and repair of ships and other craft for the Navy. Launched on 1st June 1918, the ‘Directory of Vessels chartered by Naval Districts’ lists ‘Concrete Barge No.1’, Registration number 2531, as being chartered by the Navy from Louis L. Brown at $360 per month from 11th September 1918. In Spring 1918, the Navy Department had commissioned twelve, 500 Gross Registered Tonnage barges from three separate constructors in Spring 1918 to be used in New York harbour.  Navy Barge #516 which was the first prototype. It is believed that the barge at Rondout Creek is this particular barge based on the subtly different lines of her bow. Possibly photographed when inspected by the Third Naval District on 5 April 1918. She was assigned registry ID # 2531. This barge, chartered by the Navy in September 1918, was returned to her owner on 28 October 1919. While in Navy service she was known as Coal Barge # 516. U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph. AuthorsRichard Lewis and Erlend Bonderud have been researching concrete ships worldwide for many years. They have identified over 1800 concrete ships, spanning the globe, of which many survive. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's note: The following text is from the February 1937 issue of "The Open Road for Boys" magazine. The language, spelling and grammar of the article reflects the time period when it was written. With cramped fingers, Tim Grayson shifted the tiller of the Snow Queen a fraction of an inch. Instantly the iceboat responded, veering across the hard black ice toward Lighthouse Point. Tim allowed himself one backward glance. Raleigh Bryan in the Penguin was close behind, with one leg of the race still to go. As the two ice yachts neared the southern side of the lighthouse, Tim prepared to make an extra tack to avoid a line of soft ice behind a small red marker. For a moment he was tempted not to go about. It was so cold that day that he didn’t see how there could be any soft ice left. The red marker had nothing to do with the race course; it was just a danger warning, Tim knew, and the extra tack would cost several seconds of precious time. But Tim’s conscience won, and in another minute he put his rudder hard alee to make the tack. When he came back on his original course he found the Penguin twenty yards ahead of him. Raleigh Bryan hadn't bothered about the red marker! In spite of the cold, little drops of sweat ran down Tim’s back as he shifted his position in the stern of the boat. He knew that his safety tack had cost him the race; but, as he saw it, there was nothing else to do. It wasn’t the risk to himself that had influenced Tim. He could swim in any water, and from the crowd on shore watching the race, many friends would have rushed instantly to haul him out. It was the Snow Queen that would have suffered had they gone through. Staved-in framework, warped rudder, ruined varnish —all threatened an iceboat that broke through the surface, and the Snow Queen belonged to Greg, Tim’s older brother. With all the skill at his command, Tim fought to regain the distance lost, but the Penguin held most of her lead. Tim realized that his last chance to win had vanished; and with this race went the opportunity to pilot the Snow Queen in the Navesink Yacht Club Regatta. Greg had told him he could sail in the Navesink contest if he took first place in one of the Shrewsbury (NJ) skeeter races. And this was the last race of the season. In another minute Raleigh had cut expertly across the line amid cheers from the crowd. “Nice work, Raleigh!” Tim shouted across the icy basin. Raleigh smiled his slow, confident smile. “You all would have trimmed me if you hadn’t been so scary about gettin’ your feet wet,” he drawled, as he led the way into the boat house, Tim never forgot the next half hour. Slowly came the amazing realization that the majority of the crowd thought him a coward. He found himself floundering in the knowledge of their contempt. “What’s the matter, Tim? Afraid of a cold bath?” Red Harris blurted out. “You'd have won that race if you hadn’t been such a, sissy about that soft-ice marker.” Tim’s mouth was still open when he heard Greg beside him. “There’s no use explaining,” Greg said quietly. “People either understand or they don’t. Everybody doesn’t feel the same way about a boat.” Tim looked up at his brother gratefully. At least Greg knew that he hadn’t been afraid of getting wet. “What I didn’t like,” Greg went on, “was the way you made the tack and then your attempts to shift your weight on the last leg.” In his slow, deliberate voice Greg analyzed every inch of the race until Tim fully understood his mistakes. Next day came a sudden thaw. Tim decided that it would be warm enough to work on the Snow Queen out of doors. Greg had suggested a few adjustments in the rigging, and his brother was anxious to carry them out. The thought of meeting people at the boat house so soon after losing the race was unpleasant, but Tim was glad to have something that forced him to get the ordeal over with. The boat house belonged to the township of Shrewsbury and served as a clubhouse for anyone interested in sailing. Usually a crowd collected early, but today the only person in sight was Red Harris. “Hello,” said Red. “Going out?” Tim shook his head. “Nope. Just got some repairs to make.” “This thaw may weaken the ice a bit, but even so I guess you'd be safe,” Red remarked significantly. “Raleigh’s out sailing.” He was just about to ask Red to help him carry in the Snow Queen when Red pointed to the spot where the Navesink River joined the Shrewsbury. “Look at that bird go!” he said, “Doesn’t care a whoop what he does!” Tim looked and could hardly believe his eyes. Raleigh Bryan’s Penguin was tearing ahead toward the place where the fishing lights had been. “It isn’t safe!” Tim gasped. “They were fishing through the ice up there last night, and it won't be properly frozen over.” “Don’t worry, Grandma,” Red’s voice was sarcastic. “Raleigh can take care of himself. He’ll probably jibe.” Tim watched the Penguin skudding along before the wind and a frown came between his eyes. “Listen, Raleigh hasn’t been up north very long and I’ll bet he’s never seen ice like that before. He probably doesn’t know how dangerous it is.” Red laughed and for a minute Tim hesitated. If he went after Raleigh, and the newcomer realized all the time what he was doing, he would be thought more of a mollycoddle than ever. But if he held back and Raleigh did not recognize the circles of thin ice, what then? As the Penguin kept straight on for the spotted ice, Tim grabbed a boat hook and flung it on board the Snow Queen. “You can laugh all you like,” he shouted back at Red Harris. “I’m going to stand by.” Hardly had his little boat got under way when the bow of the Penguin faltered in one of the thinly covered holes. In another instant came the sound of ripping ice and wood. The Penguin’s mast crumpled; her sail flapped and fell; half of her frame disappeared under water. Tim now could see Raleigh’s terrified face just above the water. He was fighting wildly against the current, handicapped by a tangle of rope and canvas. Working fast, Tim drew as near to the Penguin as he dared and spun her head into the wind. With a rattle of gear and rigging he dropped his sail. The Snow Queen still coasted forward and Tim frantically used one leg and the boat hook to check her speed. When she finally slithered to a standstill he was within thirty feet of Raleigh and the black pool of open water. Hurriedly casting off the painter, Tim threw one end of it to within a few inches of Raleigh’s shoulder. “Grab it!” he shouted, but Raleigh shook his head desperately. “I can’t!” he gasped. “My feet are caught and I’ve done something to my left arm. The current’s too strong. I tell you, I can’t let go.” Tim was already overboard, carrying the boat hook in one hand. “I’m coming,” he called reassuringly. But as he spoke the ice creaked threateningly beneath him. Dropping on his stomach, he began inching his way forward. When he came within a few feet of Raleigh the ice dipped under his weight, letting water ooze out over the surface to drench his chest and legs. Every second he expected the groaning ice would give way and throw him into the driving current. He could hear the rush of the water and could see that it was pushing the Penguin further under the ice. In another minute Raleigh would have to let go of her stern or be dragged under with it. In spite of wet hands, clumsy with cold, he fastened the painter around the end of the boat hook and thrust it toward Raleigh. “Stay just as you are,” he ordered, “I think I can get the rope round you. If I come any nearer, I'll break through.” “R-right,” Raleigh muttered from between blue lips. Maneuvering carefully with the boat hook, Tim finally looped the rope around Raleigh’s body. Once, as he drew it back, it slipped and started sliding snake-like toward the water. Tim reached for it with the hook and retrieved it just in time. “All set,” he shouted to Raleigh and began pulling on the rope; but instead of extricating the other pilot, he felt himself being drawn forward toward the open water. Unable to get a grip on the ice with his feet, Tim knew that continued pulling would only send him into the water. Casting about desperately for a solution of his difficulty, Tim thought of the Snow Queen. “Hold on,” he yelled, scrambling backward, “I’ll have you out pronto!” But he felt little of the confidence his words implied, for he could see that Raleigh was weakening fast and might be drawn under at any minute. Furiously Tim worked himself toward the ice boat. Trembling in his haste, he made the painter fast to a cleat at the stern. He knew he would now need every ounce of the skill Greg had tried to teach him. “Hang on to the rope with your good hand,” he shouted to Raleigh, “and when we begin to move try to kick clear.” Swiftly he shoved the Snow Queen’s bow in the direction he wanted to go and hoisted her sail. Then, hands grasping the boat, he ran alongside, pushing her forward. As he wind filled her sail, he jumped aboard. Would she start with Raleigh’s weight acting as an anchor? Would the drowning boy be able to kick himself free? Was the painter long enough to give them a chance? Tim looked back breathlessly. He moved the rudder lightly. “Go to it, Snow Queen!” he said under his breath. As if the little boat understood, she strained forward and Raleigh came sprawling across the ice like a gigantic fish. Just how he got him on board, Tim was never sure, but somehow he stopped the boat long enough to haul the half-frozen boy beside him. “How did—” Raleigh began, as Tim shoved him close to the center rail in the middle of the boat. “Don’t try to talk,” Tim snapped, his whole attention concentrated on getting the boat to shore, “Just hang to that safety rail with your good arm.” When they reached the basin in front of the boat house Greg was standing on the ice beside Red Harris, a pile of sails in his arms. “We—we—were just coming after you,” Red sputtered but Greg said nothing. Dropping the sailcloth, he reached a helping hand to Raleigh and half carried him toward the house. “Hurry up, Tim,” he ordered, “you've got to get on some dry clothes yourself.” “How about the Queen?” Tim began, but Red hastily interrupted. “l’ll put her up for you, Timmy,” he said. Relieved, Tim raced after Greg into the stuffy warmth of the boat house. In a few minutes Greg had Raleigh dressed in some old dungarees, a torn sweat shirt, and a heavy blanket that he’d found lying about. Around Raleigh’s bruised wrist he had fashioned a temporary bandage. In spite of the heat, Raleigh’s teeth were still chattering; but the color had come back to his lips and his cheeks no longer looked green. As he stuttered and stumbled through his story, Tim realized that it was exactly as he had surmised. Raleigh was practically on top of the newly frozen over fishing holes before he recognized the danger. Once in the water, his feet caught in the ropes and it was impossible for him to do more than keep himself afloat. “I still don’t see how you got across that ice,” he declared, turning to Tim, “It was the bravest thing I ever have seen!” “Tim’s never been accustomed to shy from danger,” Greg said dryly, as Red Harris poked his flaming head around the door to tell them that two men from the Navesink Yacht Club had succeeded in pulling the battered Penguin ashore. In about half an hour, the blood was coursing warmly through Raleigh’s veins and Greg thought it was safe to take him home. When they left him at his door he was still praising Tim’s bravery. “Well,” said Greg, as they drove off, “I guess that squelches any rumor about your losing yesterday’s race because you were afraid of a ducking. But what pleases me most, Timmy boy, is the way you handled the boat just now. You sailed her like a veteran! If you do anything like as well in the Navesink Yacht Club Race you ought to win it hands down!” Editor's Note: As mentioned in the 6/30/2023 blog, “Ice Yachting Winter Sailboats Hit More Than 100 m.p.h. by John A. Carroll, The Detroit Ice Yachting Club has fostered one of the more exclusive organizations in the world - the Hell Divers. To be eligible, a yachtsman merely has to take the plunge and survive to tell the story.” It appears that Raleigh became a Hell Diver by his harrowing experience. To learn more about the fishermen who created the circles on the ice, go to New York Heritage HRMM Commercial Fishermen oral histories here. Author"Circles on the Ice" by L. R. Davis and Illustrated by R. B. Pullen; "The Open Road for Boys" magazine February 1937. From the Ray Ruge Collection, Hudson River Maritime Museum. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's note: The following text is from articles printed in the New York City area newspapers in 1895 and 1920.. Thank you to Contributing Scholar Carl Mayer for finding, cataloging and transcribing this article. The language, spelling and grammar of the article reflects the time period when it was written. SPOONING PARTIES. How These Commendable Aids to Matrimony Should Be Conducted. “Spooning” parties are popular in some quarters. They take their name from a good old English word which was intended to ridicule the alleged fantastic actions of a young man or a young woman who is in love. For some reason, which no one ever could explain, everybody pokes fun at the lover. In fact, that unhappy character is never heroic in real life, no matter what great gobs of heroism are piled about him on the stage, and in all the romantic story books. The girl in love and the boy in love are said to be “spoony.” When a “spooning" party is given, the committee in charge of the event receives a spoon from each person who attends, or else presents each guest with a spoon. These spoons are fancifully dressed in male and female attire, and are mated either by the similarity of costume or by a distinguishing ribbon. The girls and boys whose spoons are mates are expected to take care of each other during the continuance of the social gathering. Of course the distribution of the spoons is made with the greatest possible carefulness, the aim being to so place them as to properly fit the case of the young people to whom they are presented. The parties are usually given by the young people of some neighborhood where the personal preference of each spoony is well known, and they are the source of no end of fun. It is possible also that they serve as aids to matrimony as well, and are therefore commendable, since an avowal is made more easy to a diffident swain after he feels that his passion is not a secret, but that his weakness for a ‘‘spoony'’ maiden is known to his friends and enemies on the committee which dispenses the spoons. It may be mentioned that after the spoons have been distributed among the guests, each couple retires for consultation regarding the reasons which caused the award of mated spoons in their case. This consultation is known by the name of "spooning.’’--St. Louis Republic .via The Yonkers Herald, June 24, 1895 High Cost of Living leads to loss of the Courting Parlor “Don't love in Gotham-- You've got no place to go; You can't hide in the subway Or on the roofs, you know! The cop that's on the corner Has got his eye on you-- Don't love in Gotham-- You'll be ‘pinched’ if you do!" SO sang Tom Masson—or, in words to that effect—some ten years ago, but the tragi-comic warning is just ten times as true this summer. For one of the problems of 1920 in merry old Manhattan is the H. C. of L., which in this connection should be translated the High Cost of Loving! Cupid knows it always has been a dilemma for New Yorkers. In all the side streets, east or west, there isn’t a piazza with rambler roses curtaining it and a hammock swung across one comer, there isn't a circular seat built around a drooping elm or broad spreading maple, there isn't a lovers' lane or a Ben Bolt “nook by a cool running brook.” No got. No can do. But now courting must be conducted between the devil of the profiteering landlord and the deep sea of propriety. For the simple truth is that almost no New Yorker can afford have a parlor for his daughter's beaux, that daughter herself can't find a house with a parlor in it, if she ls boarding. The rent laws passed at Albany do not prevent anybody from ejecting Cupid. And he is quite literally put out on the sidewalk—or into the park. The easiest way for the “new poor” —the thousands with stationary salaries—to pay their rent is simply to let an outsider pay rent for that extra room, once the courting parlor. The tenements long ago learned to use the “roomer" to cope with the landlord. The flats and apartments are profiting by the lesson. As for the boarding-house landladies, who can blame those harassed women for filing every room under their roofs to help pay the butcher and the baker? President Hibben of Princeton was complaining recently about the frankness and lack of reserve between the young men and women of to-day, but even these candid souls have not reached the point where they'll do their courting in the bosom of their families. If the parlor and solitude a deux is not for them, then neither is the family living room! Hence it is that there never were so many spooners in Central Park as there are to-day—I mean to-night. Every bench is a kissing bench. And the rush is such that two loving couples often are forced to seek accommodations on the same bench! Not even the rain drives them off. When it pours too hard they simply seek refuge in the tunnels. The Park cops are being worn out by their job as civic chaperones [sic]; the Park squirrels, from being interested, and then shocked, are now merely bored. And the deep sea of propriety is much vexed. “How can nice girls make love so publicly!” indignantly exclaim the old maids of either sex. "Nothing like that goes with us," declares the Hudson River Day Line, or, to quote exactly its recent announcement, “All spooning is tabooed from the decks of the boats. We request that the conduct of the young people shall be above criticism. The young women can help largely to control the situation.” Maybe they can—if they take Mr. Masson's advice and "don't love in Gotham.” But if a nice young clerk is so ill advised as to fall in love with a nice young stenographer, will you tell me just how they can do their courting? He can't “say it with flowers.” Theatre tickets, candy—nice candy. There articles are in the luxury class, nowadays, even for ardent lovers. She has no parlor in which she can receive him. They can't afford to go to a decent restaurant and buy enough lemonades, after dinner, to give them the privilege of spending the evening there. There remain the park, the seat on top of the bus, the Coney Island boat —public enough, heaven knows, but at least populated by strangers and not by a too observant family. There is also the sapient scheme of the rookie who took his girl to the Pennsylvania Station, rushed to the gate with her when a train was announced, bade her a fond, an osculatory farewell—then sneaked back to the waiting room and encored the performance when the gates were opened for the next departing train and the next and the next! Who knows but the much criticized cheek-to-check dancing is not merely a pathetic attempt to make love in the face of a cold and hostile world? “Romance is dead, but all unseen romance jazzed up at nine-fifteen, to paraphrase Mr. Kipling. But don't let anybody think he has solved the housing problem until he brings back the beau parlor or gives us a just-as-good substitute. From the New York Evening World, July 14, 1920 DAY LINE TABOOS SPOONING - Hudson Boats to Have Community Song Services. Beginning yesterday, “spooning" was tabooed on the boats of the Hudson River Day Line. Thousands of circulars will be distributed today setting forth the new "directions" of Ebon E. Olcott, the President. "We have said many times that some share of the comfort and enjoyment of the Sunday boat rides rests with each and every one on board.” says the circular. "Will you help us make the memory of these trips wholesome and full of enjoyment? We request that the conduct of the young people shall be above criticism. ... ." There will be a "community service" on the boats each Sunday and a religious service at Pavilion No. 2, at Bear Mountain. From The New York Times, June 13, 1920. Find a summary of this topic here. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor’s Note: The following text is a verbatim transcription of an article featuring stories by Captain William O. Benson (1911-1986). Beginning in 1971, Benson, a retired tugboat captain, reminisced about his 40 years on the Hudson River in a regular column for the Kingston (NY) Freeman’s Sunday Tempo magazine. Captain Benson's articles were compiled and transcribed by HRMM volunteer Carl Mayer. This article was originally published December 30, 1973. Fog, that natural phenomenon so prevalent on the river in the fall and spring when the seasons change, has constantly been a problem to boatmen. Obviously, there is always the danger of collision or grounding. Today, the electronic marvel of radar has done much to lessen the danger of the boatmen’s old foe. Prior to World War II, however, there was no radar. Then, the boatmen had nothing to rely upon except their boat’s compass, the echo of their boat’s whistle off the river bank, and their own knowledge of the river with all its tricks of tide, wind and twisting-channels. Few people on shore, unless they at one time had worked on the river, ever realized how extensive and uncanny this knowledge was. Years ago, probably the best men on the river in fog were the captains and pilots of the Cornell Steamboat Company’s big tugboats - the tugs that pulled the big tows of that era, sometimes with as many as 50 or 60 barges and scows in a tow. They had to be good. A steamboat pilot could almost always anchor. But on the big tugs, when the fog would close in with the tide underfoot with a big tow strung out astern and no room to round up and head into the tide, they had no choice but to keep going. One time, back around 1930, there was a company in New York harbor that specialized in the towing of oil barges. Their tugs would push oil barges up the Hudson River and through the New York Barge Canal to cities like Utica, Syracuse and Buffalo. One day one of their tugboats was pushing an oil barge up the river, destined for Buffalo, when off Tarrytown it began to get very foggy. At the time they were overtaking a big Cornell tow in charge of the tug "J. C. Hartt.” As the fog was getting thicker, the captain of the small tug pushing the oil barge went up to the tail end of the Cornell tow and put a line from the oil barge on to the last barge in the ‘‘Hartt’s” tow. He held on until the fog cleared up near Bear Mountain and then let go and went on his way. About two weeks later, when the canal tug and its oil barge got back to New York, the tug captain’s boss came down to the dock and said, “Cap, were you holding on a Cornell tow about two weeks ago?” The tug captain was sort of flustered and sputtered, "Why, why when?” “Well,” replied the boss, “we've got a bill from Cornell here for $65 for towing from Tarrytown to Bear Mountain,” and he then mentioned the times and the date. The oil barge tug’s captain knew his boss had the goods on him, so all he could say was, “Yes, that’s right. I was caught in fog off Tarrytown when they were going by. And you know those Cornell men know the river in fog better than anybody. I knew I'd be safe hanging on and sailing along with them. The boss said, “Well, I guess we'll have to pay it, but don't do it again.” I am sure many other canal tugs did the same thing, some getting away with it and some not. As they used to say along the river, the men on Cornell's steady pullers were the best compasses on the river. Now, those able boatmen, men like Ira Cooper, Al Hamilton, Ben Hoff, Sr., Jim Monahan, John Sheehan, Jim Dee, Albert Van Woert, John Cullen, Dan McDonald, Barney McGooey, Larry Gibbons, Howard Palmatier and a host of others, have long since steered their last tugboat through a fog. And those big, powerful steady pullers, tugboats like the “J. C. Hartt,” “Geo. W. Washburn,” "John H. Cordts,” “Edwin H. Mead,” “Pocahontas,” “Osceola” and “Perseverance” have all towed their final flotilla of scows and barges. Gone forever are the big tugboats with their red and yellow paneled deck houses and towering black smokestacks with their chrome yellow bases. The only thing that remains constant is the River with its changing tides. And the fogs of spring and autumn. AuthorCaptain William Odell Benson was a life-long resident of Sleightsburgh, N.Y., where he was born on March 17, 1911, the son of the late Albert and Ida Olson Benson. He served as captain of Callanan Company tugs including Peter Callanan, and Callanan No. 1 and was an early member of the Hudson River Maritime Museum. He retained, and shared, lifelong memories of incidents and anecdotes along the Hudson River. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's Note: This article, "'Companionship and a Little Fun': Investigating Working Women’s Leisure Aboard a Hudson River Steamboat, July 1919," written by Austin Gallas and published in Lateral 11.2 (2022). https://csalateral.org/issue/11-2/companionship-and-a-little-fun-investigating-working-women-leisure-hudson-river-steamboat-1919-gallas/#:~:text=The%20investigator's%20written%20account%20offers,Hudson%2C%20and%20how%20Progressive%20reformers Article Abstract: This article provides an in-depth consideration of a single report penned on the night of July 27, 1919 by a private detective employed by New York City's Committee of Fourteen (1905-1932), an influential anti-vice and police reform organization. A close reading of the undercover sleuth's account, which details his experiences, subjective judgments, and general observations regarding moral and social conditions while aboard the "Benjamin B. Odell", a palatial Hudson River steamboat enables us to enrich our grasp of the courtship and pleasure-seeking practices popular among working women and men active in New York City's heterosocial and largely segregated amusement landscape during the so-called "Red Summer". Specifically, the report reveals how wage-earning women articulated femininity and sought individual freedoms, companionship, pleasure and romance via Hudson River steamboat excursions. AuthorAustin Gallas recently earned a PhD in Cultural Studies from George Mason University, where he currently teaches in the Department of Communication. His dissertation is titled "Value of Surveillance: Private Policing, Bourgeois Reform, and Sexual Commerce in Turn-of-the-Century New York." Austin's current research interests include undercover surveillance in New York City history, Progressive Era urban police reform, American literary journalism during prohibition, and the sexual and gender politics of the American minimum wage debate of the 1910s. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's Note: The following text is a verbatim transcription of an article written by George W. Murdock, for the Kingston (NY) Daily Freeman newspaper in the 1930s. Murdock, a veteran marine engineer, wrote a regular column. Articles transcribed by HRMM volunteer Adam Kaplan. Daniel Drew The “Daniel Drew” was another of the wooden-hull vessels constructed by Thomas Collyer of New York city, built in 1860, with a hull measuring 224 feet The engine of the “Daniel Drew” was from the steamboat “Titan.” On June 5, 1860, the “Daniel Drew” appeared on the Hudson river and was placed in regular service between New York and Albany. She was an exceptionally fast vessel, making one run in October of the same year, of six hours and 31 minutes traveling up the river and making nine landings. She was a very narrow boat when she first appeared on the river and was at times rather cranky, but this factor was one of the reasons for her ability to attain such high speed. In 1862 she was widened five feet. James Collyer and other boatmen controlled the “Daniel Drew” until September 25, 1863 when she was sold to Alfred Van Santvoord and another group of steamboat men. On October 7 of the same year, Van Santvoord and company also purchased the “Armenia,” and so was laid the foundation of the present Hudson River Dayline. In 1864 the “Chauncey Vibbard” was built to run as a consort to the “Daniel Drew,” and then the “Armenia” was used as a spare boat and for occasional excursions. For many years the “Daniel Drew” and “Chauncey Vibbard” plied the waters of the Hudson river on regular schedule, and then it became necessary to have a new boat. The “Albany” was then placed in service on July 2, 1880, and the “Chauncey Vibbard” was retained to run as the new boat’s consort. The “Daniel Drew” was placed in reserve and the “Armenia” was sold for service on the Potomac river where she was destroyed by fire in 1886. On a Sunday afternoon, August 9, 1886, as the “Daniel Drew” was laying at Kingston Point, she caught fire from the engine house of the Delaware and Hudson Canal Company and was totally destroyed. Thus ended the career of another of the famous steamboats of the Hudson river. AuthorGeorge W. Murdock, (b. 1853-d. 1940) was a veteran marine engineer who served on the steamboats "Utica", "Sunnyside", "City of Troy", and "Mary Powell". He also helped dismantle engines in scrapped steamboats in the winter months and later in his career worked as an engineer at the brickyards in Port Ewen. In 1883 he moved to Brooklyn, NY and operated several private yachts. He ended his career working in power houses in the outer boroughs of New York City. His mother Catherine Murdock was the keeper of the Rondout Lighthouse for 50 years. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's note: The following text is from articles printed in the New York Times in February, 1860. Thank you to Contributing Scholar Carl Mayer for finding, cataloging and transcribing this article. The language, spelling and grammar of the article reflects the time period when it was written. New York Times - 1860-02-15 page 8 Bloody Affray on the Ice at Port Ewen. - TWO MEN KILLED, ONE FATALLY WOUNDED, AND ANOTHER BADLY HURT. Great excitement has existed in and around Port Ewen, Ulster County, during the last two or three days, in consequence of a shocking and bloody affray which occurred on the ice opposite that village on Saturday afternoon last, [Feb. 11, 1860] about 3 o’clock. The facts are as follows: Two brothers, named RILYEA, with a friend, all residing at Esopus, Ulster County, were sailing in an ice-boat on the river on Saturday afternoon. After amusing themselves for sometime, they fastened the boat to the dock at Port Ewen, and went into a tavern to drink. While there, three Irishmen took possession of the boat, loosed it from the dock, and sailed to the middle of the river, where they were observed by one of the brothers, who instantly went to them demanded the boat. The Irishmen refused to surrender it, and angry words ensued. During the altercation, young RILYEA unfastened the tiller and threatened to drive out the occupants of the boat. Upon this, one of the Irishmen drew knife from his pocket and stabbed the unfortunate [22 year old] youth in the heart, inflicting a fatal wound. The remaining brother and his friend witnessed the transaction from the shore and immediately started for the scene of the affray. Before they arrived at the boat, however, they came to the place where the elder RILYEA lay, and seeing that he was dying, rushed towards the boat to take revenge. After a short fight, one of the Irishmen seized the tiller and struck the friend of the brother a severe blow upon the head, which felled him senseless, [cracked his scull and lead to his demise]. HIRAM RILYEA then repaired to the tavern where he procured a pistol, and returning to the boat, shot one of the Irishmen, killing him instantly. He then turned and [despite being badly hurt,] ran for the shore in the direction of Rondout, followed by the remaining Irishmen, where he arrived in advance of them, and instantly gave himself up to the authorities. The brothers RILYEA were 20 and 22 years of age respectively. The one who was killed was buried on Sunday. Both the offenders have been arrested. New York Times, Feb. 17, 1860, Page 5 The Grand Jury of Ulster County, which has been for several days in session at Kingston, adjourned on Wednesday, after having disposed of about thirty cases, in various forms. The most important of them was the affair at Port Ewen, which took place on Saturday last. The case, as laid before the Grand Jury, differs essentially from the reports formerly printed, and is substantially thus: On Saturday morning, two brothers, named HIRAM and JEREMIAH RELYEA [sic], with a friend, JOHN SLATER, while cruising down the river on the ice, with an iceboat, landed at Port Ewen, a small village, inhabited mainly by Irish, employes of the Delaware and Hudson Canal Company. It seems that HIRAM RELYEA and SLATER proceeded some distance back of the village, while JEREMIAH remained to take charge of the boat. While thus engaged he was surrounded by a gang of ruffians of the place, was terribly beaten and obliged to flee for his life. Thus matters stood until about 5 o'clock P. M., when Hiram and Slater returned to take the boat, when they were also attacked by the gang, and being surrounded upon all sides were obliged to fight for their lives. At this juncture RELYEA and SLATER endeavored to take refuge between two canal boats near by, but were still more closely pursued, and RELYEA was felled to the ground by a heavy blow from MARTIN SILK. Instantly springing to his feet, he discharged a pistol at SILK, the ball of which passed through the heart of his assailant, killing him instantly. RELYEA immediately fled toward Rondout, about a mile distant, pursued by a crowd of over a hundred infuriated Irishmen. When he reached the village he was covered with blood, and his clothes nearly torn from him by the crowd. He immediately gave himself up to the authorities. A scene of the greatest excitement prevailed in Rondout, and for a time it was with difficulty that a serious riot between the canal men and the citizens was prevented. Both HIRAM and JEREMIAH RELYEA now lie in a critical condition. Doubts are entertained of the recovery of the latter. Coroner DUBOIS on Saturday proceeded to hold an inquest on the body of SILK, who, with the jury impaneled, after much opposition by the friends of deceased, found a verdict in accordance with the above facts. The Grand Jury on Tuesday refused to find a bill against HIRAM RELYEA, on the charge of killing MARTIN SILK, admitting the ground of self-defence. Indictments were found against PATRICK KINNY, TOBIAS BUTLER, PATRICK MORAN, and some six other rioters, charged with “assault with intent to kill.” Warrants were issued, and those named have been arrested. 1860-02-17 New York Daily Herald Iceboat Affray - The Tragedy on the Ice at Port Ewen. ADDITIONAL PARTICULARS —SPEEDY JUSTICE BY THE GRAND JURY OF ULSTER COUNTY. The Grand Jury of Ulster county, which for several days past has been in session at Kingston, adjourned on Wednesday, after having disposed of some thirty cases, the most important of which however, was the affair which took place at Port Ewen, about three miles south of Kingston, on Saturday last. The case was laid before the Grand Jury on Tuesday, at which time the true facts in the same appeared, and are in substance as follows: On Saturday morning last two brothers, Hiram and Jeremiah Relyea, together with a friend, John Slater, while cruising down the river on the ice in an ice boat, landed at Port Ewen, a small village, populated for the most part by Irishmen employed on the Delaware and Hudson Canal, which has its terminus at that point, and a community bearing no favorable reputation. It seems that Jeremiah Relyea and Slater proceeded some distance back of the village, while Hiram remained to take charge of the boat. While thus engaged he was surrounded by a crowd of ruffians—representatives of the village—and Relyea was severely beaten and driven away. Thus matters stood until about five o'clock in the afternoon, when Jeremiah and Slater returned to take the boat, &., when they were also attacked, and, being surrounded upon all sides, were obliged to fight for their lives. At this juncture, Relyea and Slater endeavored to take refuge between two canal boats near by, but were still closer pursued, and [Hiram] Relyea was felled to the ground by a heavy blow from Martin Silk. Instantly springing to his feet, he discharged a pistol at Silk, which took effect, the ball passing through the heart, killing him instantly. Relyea immediately fled towards Rondout, about a mile distant, pursued by a crowd of over a hundred infuriated Irishmen, which place he, however, reached, covered with blood and his clothes nearly torn from him by the mob. He instantly gave himself up to the authorities. A scene of the greatest excitement prevailed in the village, and for a time it was with difficulty that a serious riot between the Irish canal men and the citizens was prevented. Both Hiram and Jeremiah Relyea now lay in a very critical condition, and doubts are entertained of the recovery of the latter. Coroner Dubois on Saturday proceeded to hold an inquest on the body of Silk, who, with the jury empannelled [sic], after much opposition by the friends of deceased, found a verdict in accordance with the facts as stated. The Grand Jury, at Kingston, on Tuesday acquitted Hiram Relyea on the charge of killing Martin Silk, upon the grounds of self defence. It further found bills of indictment against Pat Kinney, Tobias Butler, Pat Moran and some six others on the charge of ‘‘assault with intent to kill." Warrants were issued for their arrest, and those named are now in jail. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's note: The following text is from the "Register of Pennsylvania", August 14, 1830. Thank you to Contributing Scholar George A. Thompson for finding, cataloging and transcribing this article. The language, spelling and grammar of the article reflects the time period when it was written. A Trip On The Delaware & Hudson Canal To Carbondale. New York, August 2d, 1830. Mr. Croswell -- I perceive by the paper, that a packet boat commences this day, to run regularly for the remainder of the season, on the Delaware and Hudson canal. Among the pleasant and healthy tours that are now sought after, I would strongly recommend a trip on that canal. It leads from Bolton, on the waters of the Hudson and Kingston Landing; to Carbondale on the Lackawanna, which falls into the Susquehanna. I had the satisfaction not long since to visit that country, and I was delighted with the beauty and grandeur of the scenery, and the noble exhibition of skill, enterprize and rising prosperity, which were displayed throughout the course of that excursion. This great canal, though seated in the heart of the state, seems to be almost unknown to the mass of our tourists. Its character, execution and utility, richly merit a better acquaintance. It commences at Eddyville, two miles above Kingston, and we ascend a south-west course along the romantic valley of the Rondout, and through a rich agricultural country in Ulster county, which has been settled and cultivated for above a century. the Shawangunk range of mountains hangs on our left; and as we attain a summit level at Phillips or Lock Port, 35 miles from the commencement of the canal, after having passed through 54 lift-locks, extremely well made of hammered stone laid in hydraulic cement. The elevation here is 535 feet above tide water at Bolton, and the canal on this summit level of 16 miles, is fed principally by the abundant waters of the Neversink, over which river the canal passes in a stone aqueduct of 324 feet in length; and descends through 6 locks to Port Jervis, at the junction of the Neversink and Delaware rivers, and 59 miles from the landing. The canal here changes its course to the north-west, and ascends the left bank of the majestic Delaware, through a mountainous and wild region, to the mouth of the Laxawaxen [sic], at the distance of 22 miles from Port Jervis. In this short course the canal is mostly fed by the large stream of the Mongauss, which it crosses, and in several places and for considerable distances, it is raised from the edge of the bed of the Delaware, upon walls of neat and excellent masonry, and winds along in the most bold and picturesque style, under the lofty and perpendicular sides of the mountains. the Neversink, the Mongauss, the Lackawaxen [sic] and the Delaware were all swollen by the heavy rains when I visited the canal, and they served not only to test the solidity of the work, and the judgment with which it was planted, but to add greatly to the magnificence of the scenery. At the mouth of the Lackawaxen we crossed the Delaware upon the waters of a dam thrown across it, and entered the state of Pennsylvania, and ascended the Lackawaxen, through a mountainous region the farther distance of 25 miles to Honesdale, where the canal terminates. This new, rising and beautiful village, is situated at the junction of the Lackawaxen and Dyberry streams, and is so named out of respect to Philip Hone, Esq. of New York, who has richly merited the honor by his early, constant and most efficient patronage of the great enterprize of the canal. The village is upwards of 1000 feet above tide water at Bolton, and at the distance of 103 miles according to the course of the canal. There are 103 lift and two guard locks in that distance, and the supervision of the locks and canal, by means of agents or overseers in the service of the company, and who have short sections of the canal allotted to each, appeared to me to be vigilant, judicious and economical. The canal and locks, by means of incessant attention, are sure to be kept in a sound state and in the utmost order. The plan and execution of the canal are equally calculated to strike the observer with surprise and admiration. He cannot but be deeply impressed, when he considers the enterprising and gigantic nature of the undertaking, the difficulties which the company had to encounter, and the complete success with which those difficulties have been surmounted. This is the effort of a private company; and when we reflect on the nature of the ground, and the character and style of the work, we can hardly fail to pronounce it a more enterprising achievement than that of the Erie Canal. I hope and trust it may be equally successful. We found the most busy activity on the canal, and it was enlivened throughout its course by canal boats, (of which there were upwards of 150) employed in transporting coal down to the Hudson. At Honesdale a new and curious scene opens. Here the rail-way commences, and it ascends to a summit level of perhaps 850 feet on its way to Carbondale, a distance of 16 miles and upwards. It terminates in the coal beds on the waters of the Lackawanna, at the thriving village of Carbondale. The rail-way, is built of timber, with iron slates fastened to the timber rails with screws, and in ascending the elevations and levels, the coat cars are drawn up and let down by means of stationary steam-engines, and three self-acting or gravitating engines moving without steam. Nothing will more astonish and delight a person not familiar with such things, than a ride on this rail-way in one of the cars. A single horse will draw 16 loaded cars in most places, and in one part of the distance for five miles the descent is sufficient to move the loaded cars by their own weight. A line of ten or a dozen loaded cars, moving with any degree of velocity that may be required, and with their speed perfectly under the command of the guide or pilot, is a very interesting spectacle. I don't pretend to skill or science on the subject to canals, rail-ways and anthracite coal. I speak only of what I saw and of the impressions which were made upon my mind. It appears to me that all persons of taste and patrons of merits, whose feelings are capable of elevation in the presence of grand natural scenery, and whose patriotism can be kindled by the accumulated displays of their country's prosperity, would be glad of an opportunity to see these beauties of nature and triumphs of art to which I have alluded. "A Trip On The Delaware & Hudson Canal To Carbondale." Register of Pennsylvania. August 14, 1830. 111—112. 1830-08-02 -- A Trip on the Delaware & Hudson Canal to Carbondale If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's note: The following text is from the 1819 Letters to his father by Henry Meigs describing his life in then rural Greenwich Village. Thank you to Contributing Scholar George A. Thompson for finding, cataloging and transcribing this article. The language, spelling and grammar of the article reflects the time period when it was written. 1819: N. York, Feby 6th, 1819 Dear father. Since I last wrote you, Julia + I have decided on placing our tent in the Country as we call it for the ensuing summer. Where we can live much more economically and deliciously. *** It is a decent, convenient house immediately on the North River Margin, with the beach where we can bathe, at our door. Green slopes covered with thrifty Apple trees from the road to the River, a garden large enough to exercise Henry + I. We have all this for less than I have been used to pay these 10 years, and the distance from my office is only 13000 feet! I shall bring my dinner in my Pocket in the morning + retreat at night from our noisy, noisy town and when the apple trees are dipped in flowers, I shall be able to relish Homer. [passage in Greek] *** New York, March 14, 1819. My dear brother. ** You know when one owns an apple tree, what pains one must be at to keep the young rascals from stealing all the fruits. All one has of it is to consider that apple tree owning is a troublesome business *** N. York, April 18, 1819.Dear father - Yesterday we had a very interesting display of Electricity between two and three of P. M. [the lightning followed an all-day gale; a sketch-map showing that most of the lightning strikes were on the East River, below Wall-street] My country house is so situated as to receive the full force of blowing weather. So that in the stormy nights Julia + I have been delightfully lulled to sleep by the roar of wind + rain attended with that still more pleasant music [passage in Greek]. I assure you that [illegible] waves three feet hight roll on our sand beach most agreeably. *** The weather has been damp but we are all free from colds. Julia thinks the bank of the river is drier than our City brick vaults. The passing of the river boats of all sorts is a constant amusement + interest. When the wind blows heavy you watch as far as you can see, some bumpkin schooner or sloop whose press of sail threatens him every moment with a keel up + you admire some clean painted vessel with close reefs reaching hand over hand in the wind's eye towards the Metropolis and mark at every half [?] minute the spray fly from stem to stern thus [a sketch] and when she comes about we have all the noise of the sails [illegible] shivering in the blast. Henry Meigs, Letters. N-YHS; Between two and three o'clock on Saturday last, the city was visited by a storm of rain and hail, accompanied with considerable thunder and lightning. The schooner Thames, lying at Coffee house slip, was struck by the lightning, and was on fire for a considerable time, and much damaged; three men on board were hurt by the lightning, and sent to the hospital. *** National Advocate, April 19, 1819, p. 2, col. 3; [a destructive thunderstorm] N-Y E Post, April 19, 1819, p. 2, col. 3, from Mer Adv & Gaz; N-Y D Advertiser, April 19, 1819, p. 2, cols. 1-2 New York, April 25, 1819. Dear father - *** I am at work in my Garden at about sunrise + continue for two hours. Yesterday + the day before I dug up and raked over neatly, each morning about 800 superficial feet: about as much as a common labourer would do in a whole day. It is after such labour that I take pleasure in a good shave, wash, clean shirt, &c. breakfast, 2 mile walk + then sitting at my desk with pen. Henry Meigs, Letters. N-YHS.- a plan of his grounds and house: 200 feet along the river, 260 feet deep to the road; a house apparently with porches front & back; a barn, cow shed & fowl-house; a garden, approximately 100 x 130; apple & other fruit trees; the "quidnunc necessarius" (sp?) at the river's edge] - Henry Meigs, Letters. N-YHS, undated, filed between letters of May 9 and May 12, 1819 [fish in the market sell so cheaply that he tends his garden rather than fish for flounder from "the timber raft now in front of my door"; letter of May 16, 1819] One of the greatest evils of our London is, the vile quality of the water, which is obviously produced by the 1000s of Cloacinious (sp?) structures on the surface. I moved one mile from the Coffee house 8 years ago, principally, to obtain better water, for it may be observed at every street as you remove from the South end of our City, that the water becomes better. *** In the City, our tea kettle became encrusted with stony matter to the thickness of nearly 1/4 Inch in some months. *** I met Burr day before yesterday, and his appearance, so sprightly, induced me to remark to him that he had lost nothing of the appearance of health in the last 10 years. He replied smilingly "I presume, -- I have no doubt that I shall live all the days of my life! that is my philosophy!" *** This has been as usual (Sunday) a great River sloop day. They fill up cargo by Saturday all along the Hudson and improve Sunday to reach our market, -- baaing, cackling + horse blowing it -- along with calves, sheep, fowl, fresh butter et omnia cetera farmalia. I have to day counted 8 to 10 frequently in sight, in 15 minutes. *** Henry Meigs, Letters. Letter of May 23, 1819. N-YHS. ["whole dozens of boys" come to swim in the river near his house] I am sitting in my largest room looking thro the west windows on the opposite shore. Staten Island, the river, the sloops, the boys swimming. Henry Meigs, Letters. Letter of June 6, 1819. Henry Meigs, Letters to his father. New-York Historical Society. 1819-04-18 -- Henry Meigs, Letters to his father. At New-York Historical Society. Henry Meigs, coun. & nota, 16 Nassau, h. 43 Franklin (Longworth's, 1818/19);. Henry Meigs, coun. & nota, 16 Nassau, h. Greenwich (Longworth's, 1819/20)  A more modern view of the former farmland. https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.propertynest.com%2Fblog%2Fcity%2Fgreenwich-village-manhattan-review-neighborhood-moving-guide%2F&psig=AOvVaw3pxW29IOBs6lnJaQsSKSn9&ust=1692726439999000&source=images&cd=vfe&opi=89978449&ved=0CA8QjRxqFwoTCKiYr8an7oADFQAAAAAdAAAAABAd If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

|

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 info@hrmm.org Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |