|

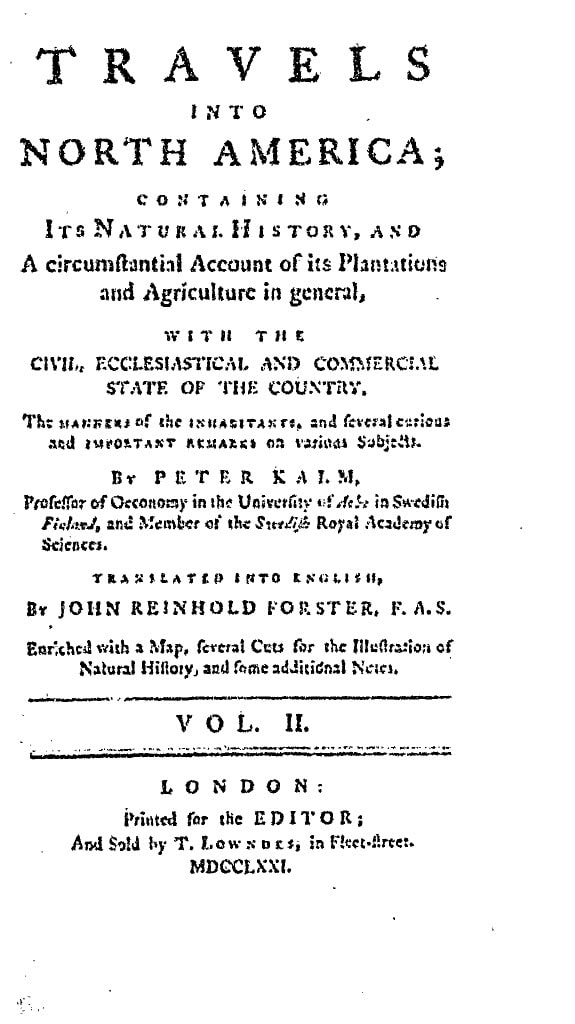

p. 227) June the 10th. [1749] At noon we left New York, and sailed with a gentle wind up the river Hudson, in a yacht bound for Albany. All this afternoon we saw a whole fleet of little boats returning from New York, whither they had brought provisions and other goods for sale, which on account of the extensive commerce of this town and the great number of inhabitants go off very well. The (p. 228) river Hudson runs from North to South here, except for some high pieces of land which sometimes project far into it, and alter its direction. Its breadth at the mouth is reckoned about a mile and a quarter. Some porpoises played and tumbled in the river. The eastern shore, or the New York side, was at first very steep and high; but the western was very sloping and covered with woods. *** About ten or twelve miles from New York, the western shore appears quite different from what it was before; it consists of steep mountains with perpendicular sides towards the river. . . . *** Sometimes a rock projects like the salliant angle of a bastion; the tops of these mountains are covered with oaks and other wood;. a number of stones of all sizes lie along the shore, having rolled down from the mountains. These high and steep mountains continued for some English miles on the western shore; but on the eastern side the land is (p. 229) high, and sometimes diversified with hills and valleys, which were commonly covered with hardwood trees, amongst which there appeared a farm now and then in a glade. The hills were covered with stones in several places. About twelve miles from New York we saw Sturgeons . . . leaping up out of the water, and on the whole passage we met porpoises in the river. As we proceeded we found the eastern banks of the river very much cultivated, and a number of pretty farms surrounded with orchards, and fine corn-fields presented themselves to our view. About twenty-two miles from New York, the high mountains . . . left us, and made as it were a high ridge here from east to west across the country. This altered the face of the land on the western shore of the river; from mountainous it became interspersed with little valleys and round hillocks, which were scarce inhabited at all; but the eastern shore continued to afford us a delightful prospect. After sailing a little while in the night, we cast our anchor and lay here (p. 230) till the morning, especially as the tide was ebbing with great force. June the 11th This morning we continued our voyage up the river, with the tide and a faint breeze. We now passed the Highland mountains, which were to the East of us. They consisted of gray sandstone, were very high and pretty steep, and covered with deciduous trees, and likewise with firs and red cedars. The western shore was rocky, which however did not come up to the height of the mountains on the opposite shore. The tops of these eastern mountains were cut off from our sight by a thick fog which surrounded them. The country was unfit for cultivation, being so full of rocks, and accordingly we saw no farms. The distance from these mountains to New York is computed at thirty-six English miles. A thick fog now rose from the high mountains like the smoke of a charcoal kiln. For the space of some English miles, we had hills and rocks on the western banks of the river; and a change of lesser and greater mountains and vallies covered with young firs, red cedars and oaks, on the eastern side. The hills close to the riverside are commonly low, but their height increased as they are further from the river. Afterwards we saw for some miles (p. 231) together, nothing but high rolling mountains and valleys, both covered with woods; the valleys are in reality nothing but low rocks, and stand perpendicular towards the river in many places. The breadth of the river was sometimes two or three musket shot, but commonly not above one; every now and then we saw several kinds of fish leaping out of the water. The wind vanished away about ten o'clock in the morning, and forced us to get forward with our oars, the tide being almost spent. In one place on the western shore we saw a wooden house painted red, and we were told, that there was a sawmill further up; but besides this we did not see one farm or any cultivated grounds all this forenoon. The water in the river has here no longer a brackish taste; yet I was told that the tide, especially when the wind is south, sometimes carries the salt water further north with it. The colour of the water was likewise altered, for it appeared darker here than before. *** (p. 232) *** I was surprised on seeing its course, and the variety of its shores. It takes its rise a good way above Albany, and descends to New York, in a direct line from North to South, which is a distance of about a hundred and sixty English miles, and perhaps more; for the little bendings which it makes are of no signification. In many places between New York and Albany, are ridges of high mountains running West and East. But it is remarkable that they go on undisturbed till they come to the Hudson, which cuts directly across them, and frequently their sides stand perpendicular towards the river. *** (p. 233) *** Quere, Why does this river go on in a direct line for so considerable a distance? Why do the many passages, through which the river flows across the mountains, ly along the same meridian? Why are there no water-falls at some of these openings, or at least shallow water with a rocky bed? We now perceived excessive high and steep mountains on both sides of the river, which echoed back each sound we uttered. Yet notwithstanding they were so high and steep, they were covered with small trees. *** The country began here to look more cutivated, and less mountainous. (p. 234) The last of the high western mountains was called Butterhill; after which the country between the mountains grows more level. The farms became very numerous, and we had a prospect of many corn-fields, between the hills: before we passed these hills we had the wind in our face, and we could only get forward by tacking, which went very slow, as the river was scarcely a musket-shot in breadth. Afterwards we cast anchor, because we had both wind and tide against us. Whilst we waited for the return of tide and the change of the wind, we went on shore. *** Some time after noon the wind arose from the South-west, so we weighed anchor, and continued our voyage. The place where we lay at anchor, was just the end of those steep and amazingly high mountains: their height is very amazing; they consist of gray rock stone, and close to them, on the shore, lay a vast (p. 235) number of little stones. As soon as we had passed these mountains, the country became clearer of mountains, and higher. The river likewise encreased in breadth, so as to be nearly an English mile broad. After sailing for some time, we found no more mountains along the river; but on the eastern side goes a high chain of mountains to the north-east, whose sides were covered with woods up to one half their height. *** The eastern side of the river was much more cultivated than the western, where we seldom saw a house, the land being covered with woods, though it is in general very level. About fifty-six English miles from New York the country is not very high; yet it is every where covered with woods, except some new farms which were scattered here and there. The high mountains (p. 236) which we left in the afternoon, now appeared above the woods and the country. These mountains, which are called the Highlands, did not project more North than the other, on the opposite side, in the place where we anchored. Their sides (not those towards the river) were seldom perpendicular, but sloping, so that one could climb to the top, though not without difficulty. On several high grounds near the river, the people burnt lime. The master of the yacht told me, that they break a fine blueish grey limestone in the high grounds, along both sides of the river, for the space of some English miles, and burn lime of it. But at some miles distance there is no more limestone and they find also none on the banks till they come to Albany. *** We cast anchor late at night, because the wind ceased and the tide was ebbing. The depth of the river is twelve fathoms here. (p. 237) The fireflies flew over the river in large numbers at night and often settled on the rigging. June the 12th. This morning we proceeded with the tide, but against the wind. The river was here a musket-shot broad. The country in general is low on both sides, consisting of low rocks, and stony fields, which are however covered with woods. It is so rocky, stony, and poor, that nobody can settle on it, or inhabit it, there being no spot of ground fit for a corn-field. The country continued to have the same appearance for the space of a few miles, and we never perceived one settlement. At eleven o'clock this morning we came to a little island, which lies in the middle of the river, and is said to be half-way between New York and Albany. The shores are still low, stony, and rocky, as before. But at a greater distance we saw high mountains, covered with woods, chiefly on the western shore, raising their tops above the rest of the country: and still further off, the Blue Mountains rose up above them. Towards noon it was quite calm, and we went on very slow. Here, the land is well cultivated, especially on the eastern shore, and full of great corn-fields; yet the soil seemed sandy. (p. 238) Several villages lay on the eastern side, and one of them, called Strasburg, was inhabited by a number of Germans. To the West we saw several cultivated places. The Blue Mountains are very plainly to be seen here. They appear through the clouds, and tower above all other mountains. The river is full an English mile broad opposite Strasburg. *** Rhinbeck is a place located a short distance from Strasburgh, further off from the river. It is inhabited by many Germans, who have a church there. *** This little town is not visible from the river-side. At two in the afternoon it began again to blow from the south, which enabled us to proceed. The country on the eastern side is high, and consists of well cultivated soil. We had fine corn-fields, pretty (p. 239) farms, and good orchards, in view. The western shore is likewise somewhat high, but still covered in woods, and we now and then, though seldom, saw one or two little settlements. The river is above an English mile broad in most places, and comes in such a straight line from the North that we could not sometimes follow it with our eye. June the 13th. The wind favoured our voyage during the whole night, so that I had no opportunity of observing the nature of the country. This morning at five o'clock we were but nine English miles from Albany. The country on both sides of the river is low, and covered with woods, excepting a few little scattered settlements. Under the higher shores of the river were wet meadows, covered with sword-grass (Carex), and they formed several little islands. We saw no mountains; and hastened towards Albany. The land on both sides of the river is chiefly low, and more carefully cultivated as we came nearer to Albany. Here we could see everywhere the type of hay-stacks with movable roofs. . . . As to the houses which we saw, some were of wood, others of stone. The river is seldom above a musket-shot broad, and in several parts of it are sandbars which require great skill in governing the (p. 240) yachts. At eight o'clock in the morning we arrived at Albany. All the yachts which ply between Albany and New York, belong to Albany. They go up and down the river Hudson, as long as it is open and free from ice. They bring from Albany boards or planks, and all sorts of timber, flour, pease, and furs, which they get from the Indians, or which are smuggled from the French. They come home almost empty, and only bring a few merchandizes with them, among which the chief is rum. This is absolutely necessary to the inhabitants of Albany; they cheat the Indians in the fur trade with it; for when the Indians are drunk, they are practically blind and will leave it to the Albanians to fix the price of the furs. The yachts are quite large, and have a good cabbin, in which the passengers can be very commodiously lodged. They are commonly built of red Cedar or of white Oak. Frequently, the bottom consists of white oak, and the sides of red cedar, because the latter withstands putrefaction much longer than the former. The red cedar is likewise apt to split, when it hits against any thing, and the river Hudson is in many parts full of sands and rocks, against which the keel of the yacht sometimes hits; therefore (p. 241) they choose white oak for the bottom, as being the softer wood, and not splitting so easily; and the bottom being continually under water, is not so much exposed to putrefaction, and holds out longer. *** (p. 244) June the 15th *** The several sorts of apple-trees grow very well here, and bear as fine fruit as in any other part of North America. Each farm has a large orchard. They have some apples here which are very large, and very palatable; they are sent to New York and other places as a rarity. They make excellent Cyder, in autumn, in the country round Albany. *** (p. 245) They sow maize in great abundance. *** They sow wheat in the neighbourhood of Albany to great advantage. For one bushel they get twelve sometimes; if the soil is good, they get twenty bushels. *** The inhabitants of the country round Albany are Dutch and Germans. The Germans live in several great villages, and sow great (p. 246) quantities of wheat which is brought to Albany, whence they send many yachts laden with flour to New York. The wheat flour from Albany is reckoned the best in all North America, except that from Sopus [Esopus] or King's Town [Kingston], a place between Albany and New York. *** At New York they pay [for] the Albany flour with several shillings more per hundred weight, that that from other places. Rye is likewise sown here, but not so generally as wheat. *** The Dutch and Germans who live hereabouts, sow pease in great abundance; they grow very well, and are annually carried to New York in great quantities. *** (p. 247) Potatoes are generally planted. *** The Humming-bird (Trochilus Colubris) comes to this place sometimes, but is rather a scarce bird. The shingles with which the houses are covered are made of White Pine, which (p. 248) is reckoned as good and as durable and sometimes better than the White Cedar. It is claimed that such a roof will last forty years. The White Pine is found abundant there, in such places where common pines grow in Europe. *** They saw a vast quantity of deal from the white pine on this side of Albany, which are brought down to New York and exported. *** (p. 249) The porpoises seldom go higher up the Hudson than the salt water goes; after that, the sturgeons fill their place. *** The Fireflies which are the same that are so common in Pensylvania during summer, are seen here in abundance every night. They fly up and down in the streets of this town. They come into the houses, if the doors and windows are open. *** (p. 252) June the 20th. The tide in the river Hudson goes about eight or ten English miles above Albany, and consequently runs one hundred and fifty-six English miles from the sea. In spring, when the snow melts, there is hardly any flowing near this town; for the great quantity of water which comes from the mountains during that season, occasions a continual ebbing. This likewise happens after heavy rains. *** The cold is generally reckoned very severe here. The ice in the river Hudson is commonly three or four feet thick. On the 3d of April some of the inhabitants crossed the river with six pair of horses. The ice commonly dissolves about the end of March, or beginning of April. Great pieces of ice come down about that time, which sometimes carry with them the houses that stand close to the shore. The Water is very high at that time in the (p. 253) river, because the ice stops sometimes, and sticks in places where the river is narrow. *** On the 16th of November the yachts are put up, and about the beginning or middle of April they are in motion again. *** *** June the 21st. Next to the town of New York, Albany is the principal town, or at least the most wealthy, in the province of New York. It is situated on the declivity of a hill, close to the western shore of the (p. 256) river Hudson, about one hundred and forty-six English miles from New York. The town extends along the river, which flows here from N. N. E to S. S. W. The high mountains in the west, above the town, bound the prospect on that side. There are two churches in Albany, an English one and a Dutch one. *** . . . all the people understood Dutch, the garrison excepted. *** The town-hall lies to the southward of the Dutch church, close by the river side. It is a fine building of stone, three stories high. It has a small tower or steeple, with a bell, and a gilt ball and vane at the top of it. The houses in this town are very near, and partly built with stones covered with shingles (p. 257) of the White Pine. Some are slated with tiles from Holland, because the clay of this neighbourhood is not reckoned fit for tiles. Most of the houses are built in the old way, with the gable-end towards the street; a few excepted, which were lately built in the manner now used. *** The gutters on the roofs reach almost to the middle of the street. This preserves the walls from being damaged by the rain; but it is extremely disagreeable in rainy weather for the people in the streets, there being hardly any means of avoiding the water from the gutters. The street-doors are generally in the middle of the houses; and on both sides are seats, on which, during fair weather, the people spend almost the whole day, especially on those which are in the shadow of the houses. In the evening these seats are covered with people of both sexes; but this (p. 258) is rather troublesome, as those who pass by are obliged to greet every body, unless they will shock the politeness of the inhabitants. The streets are broad, and some of them are paved; in some parts they are lined with trees; the long streets are almost parallel to the river, and the others intersect them at right angles. The street which goes between the two churches, is five times broader than the others, and serves as a market place. The streets upon the whole are very dirty, because the people leave their cattle in them, during the summer nights. There are two market-places in the town, to which the country people resort twice a week. *** The situation of Albany is very advantageous (p. 259) in regard to trade. The river Hudson, which flows close by it, is from twelve to twenty feet deep. There is not yet any quay made for the better lading of the yachts, because the people feared it would suffer greatly, or be entirely carried away in spring by the ice, which then comes down the river; the vessels which are in use here, may come pretty near the shore in order to be laden, and heavy goods are brought to them an canoes tied together. Albany carries on a considerable commerce with New York, chiefly in furs, boards, wheat, flour, pease, several kinds of timber, &c. There is not a place in all the British colonies, the Hudson's Bay settlements excepted, were such quantities of furs and skins are bought of the Indians, as at Albany. *** ([. 261) The Indians take in return several kinds of cloth, and other goods. . . . The greater part of the merchants at Albany have extensive estates in the country, and a great deal of wood. If their estates have a little brook, they do not fail to erect a saw-mill upon it for sawing boards and planks, with which commodity many yachts go during the whole summer to New York, having scarce any other lading than boards. Many people at Albany make the wampum of the Indians, which is their ornament and their money, by grinding some kinds of shells and muscles; this is a considerable profit to the inhabitants. *** The Inhabitants of Albany and its environs are almost all Dutchmen. They speak Dutch, have Dutch preachers, and divine service is performed in that language: their manners are likewise quite Dutch; their dress is however like that of the English. *** Peter Kalm. Travels into North America. . . , vol. 2, pp. 227-261. John Reinhold Forster, transl. London, 1771. Checked against Peter Kalm's Travels in America. The English Version of 1770. Rev. and ed. by Adolph B. Benson. N. Y.: Dover Publ., 1966, vol. 1, pp. 326-32. [left Albany on June 21, walking along the Hudson, accompanied by men in a canoe] Kalm, Peter (6 Mar. 1716-16 Nov. 1779), botanist, was born in the province of Ângermanland, Sweden, the posthumous son of Gabriel Kalm, a clergyman from Osterbotten, Finland, and Catherina Ross. (His name was actually Pehr Kalm, but his given name was anglicized in the American colonies and England.) He was educated at the Gymnasium at Vasa (or Vaasa) and in 1735 entered the Âbo Academy in Âbo, Sweden (later Turku, Finland). Although he studied theology at the academy, he was encouraged to pursue his interest in the natural sciences by Bishop Johan Brovallius, who influenced Baron Sten Carl Bjelke to support Kalm. Bjelke introduced his protégé to his rich library of natural history on his estate at Lofstad, and for the next seven years Kalm was the superintendent of Bjelke's experimental plantation.

At Bjelke's behest, Kalm went on botanical expeditions to southern Sweden and Finland. Bjelke was also responsible for introducing Kalm to the great taxonomist Carl von Linné, whose published work appeared under the Latin version of his name, Carolus Linnaeus. (Linnaeus's classifications of flora and fauna became the standard means of scientifically identifying and naming genera and species.) In 1740 Kalm entered Uppsala University to study with Linnaeus. Trained as a practical botanist, Kalm specialized in medicinal, dye-yielding, and poisonous plants and their beneficial or harmful effects. He also sought to find new, potentially useful plants and seeds, which he then grew and observed in Linnaeus's botanical garden in Uppsala. He was elected to the Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1745 and was granted the title of docent in natural history and economy (the equivalent of practical husbandry or agriculture) in 1746. In 1747 he was appointed the first professor of natural history and economy at the Âbo Academy, a position that he would retain until his death. Almost immediately, however, Kalm was given leave to undertake a scientific expedition to North America sponsored by the Swedish Academy of Sciences. He was specifically charged with finding a species of mulberry that could survive in Sweden and provide a basis for an independent silk industry. In addition, he was expected to collect other plants and seeds of plants that could perhaps be grown in Sweden. Having spent several months in England en route to North America, Kalm, accompanied by a gardener, Lars Jungström, landed in Philadelphia in September 1748. There he associated himself with Benjamin Franklin and two botanical correspondents of Linnaeus, John Bartram and Cadwallader Colden, both of whom were significant naturalists in their own right. In May 1749 Kalm embarked on a trip to New York, Albany, Lake Champlain, and Canada, seeking plants and seeds. After returning to Philadelphia in October, he again traveled to Canada in 1750. He provided one of the first descriptions of Niagara Falls in a letter to Franklin dated 2 September 1750, which was reprinted in Bartram's Travels in Pensilvania and Canada (1751; repr., 1966). Kalm resided for some time among the Swedish residents in Raccoon (now Swedesboro), New Jersey, and reported on the community's history and customs. In 1750 he married one of the residents, Anna Margaretha Sjöman, the widow of a pastor. Kalm went back to Sweden in 1751, arriving in June. While he resumed his academic responsibilities, he tended to his American plants in his own garden in Âbo and prepared his American diary for publication. En Resa til Norra America (1753-1761), published in English as Travels into North America (1770-1771), is a wide-ranging account of the natural history, social conditions, politics, and history of colonial Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, and southern Canada. It was also translated into Dutch, German, and French. Although Kalm was not the first to publish a descriptive account of travels in eastern North America, he was the first professional scientist to gather data in the field in a systematic manner and the first to publish an extensive, genuinely scientific report of his observations. As he said in his letter to Franklin concerning Niagara Falls, "You must excuse me if you find in my account no extravagant wonders. I cannot make nature otherwise than I find it. I would rather it should be said of me in time to come, that I related things as they were." Until 1778 Kalm also published numerous articles on his American travels in the transactions of the Swedish Academy of Science, seventeen in all. Although he largely failed to bring horticulturally and agriculturally significant plants to Sweden, Kalm did return with about ninety plants new to Europe. One of these, the mountain laurel, Kalmia latifolia, was named for him by Linnaeus. He died in Âbo, Sweden. Ralph L. Langenheim American National Biography

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorThis collection was researched and catalogued by Hudson River Maritime Museum contributing scholars George A. Thompson and Carl Mayer. Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 [email protected] Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed