History Blog

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Media Monday post is another teaser trailer for our forthcoming documentary film, "Seven Sentinels: Lighthouses of the Hudson River." The museum is crowdfunding for this film on Indiegogo, so help us make it a reality and get some really cool perks in return. We have made significant progress toward our goal - will you help us reach it before January 13? "Ice Guardians" is a teaser trailer look at some of the amazing footage filmmaker Jeff Mertz got of the Hudson-Athens, Rondout, and Esopus Meadows Lighthouses last winter. As we approach the holiday season, it seemed apt to share the icy beauty with everyone. The drone footage also reveals how isolating life at a lighthouse in winter could be, and how the lighthouses themselves needed to be protected from the heavy floes of ice. If you missed the first trailer, catch up below! We have already received dozens of individual donations, as well as support from Ulster Savings Bank, Rondout Savings Bank, and Ulster County Cultural Services & Promotion Fund administered by Arts Mid-Hudson. But we've still got a ways to go before we reach our goal, and just under a month to do it in.

You can help by liking, commenting on, and sharing our social media posts, YouTube videos, and this blog post. If you'd like to do more to help, you can join our individual fundraiser contest, where you can get credit for donations from family and friends on Facebook and other platforms. Check out our latest campaign update to learn more. You can earn the same perks as higher level backers. And, if you'd like to donate to the film but don't want to do so online, you can always mail us a check! Send it to the Hudson River Maritime Museum, 50 Rondout Landing, Kingston, NY 12401 and write "Seven Sentinels" or "lighthouse film" in the check memo line.

0 Comments

The Spalding Athletic Library and the American Sports Publishing Company were both founded by A.G. Spalding, owner of Spalding's Athletic Goods. Designed to produce affordable books on a wide variety of sports, rule books, and others, Spalding's conveniently included related catalogs and order forms for their goods in each inexpensive booklet. Published in 1917 and written by outdoor sports expert and author James A. Cruikshank, Spalding's Winter Sports is our featured artifact of the day, acquired by the Hudson River Maritime Museum as part of a collection of ice boating materials. And thanks to the transcription skills of volunteer Adam Kaplan, we'll be serializing each chapter of Winter Sports for the next several weeks. If you'd like to see the other sports booklets that Spalding offered (and there were hundreds), you can see some of their works digitized at the Library of Congress. The booklet features short articles on skating, skiing, snowshoeing, ice boating, tobogganing, hockey, and more. Be sure to join our mailing list to get updates and make sure you don't miss a chapter! The introduction starts below.  Interior pages of "Spalding's Winter Sports" by James A. Cruikshank, 1917. Ray Ruge Collection, Hudson River Maritime Museum. At left, the author's biography reads, "James A. Cruikshank, author of the Spalding Athletic Library book on Winter Sports, is a New Yorker by birth and residence. He has traveled widely on this and other continents at all seasons of the year. He is a recognized authority on outdoor sports, having held editorial connection with many leading publications in that field. His lectures on outdoor life have been attended by over one hundred thousand people during the past ten years." Winter sports are now a most important feature of the outdoor life of the northern half of the world. During the past ten years there has been a complete change in the attitude of the sport-loving folk of northern nations toward what was once regarded as the least interesting outdoor season of the year. Now, there are great numbers of experienced outdoor folks, familiar with the sports of the world, who do not hesitate to claim that the outdoor sports of the winter, in cold, snowy latitudes, are incomparably the most fascinating as well as the most beneficial pastimes of the four seasons. The enthusiasm of these new champions of winter is making itself felt all over the world; but especially in the United States, where outdoor sport of every kind is now enjoying the zenith of its popularity, and where there is constant demand for some new form of outdoor pastime, has the charm of the new outings on snow and ice made special appeal. Many of the most thrilling sports of the year are found among the winter pastimes. Ice Yachting knows no second for sensational features; Ski Jumping from a take-off rivals aeroplaning with its danger; Hockey is one of the most spectacular games in the whole realm of sport; and the list might be indefinitely extended. For the seeker after other forms of winter entertainment out of doors, there is to be found almost everything that could be asked from the quaint curling game of the cannie Scot to a snowshoe hunt for wolves in Canadian white silences. And for the lover of nature, in all her varied forms, there are winter beauties which rival those of summer. To stimulate interest in the charm of winter in the north, and to provide helpful information as to how some of the best winter sports may be enjoyed, is the purpose of this little book. Author James A. Cruikshank was a longtime New York resident and was an expert outdoorsman, writing and editing publications for American Angler magazine, Field and Stream, and more, as well as authoring books like Spalding's Winter Sports. He hiked, hunted, fished, boated, snowshoed, skied, ice skated, mountain climbed, camped, and more. He was also an avid photographer and gave public talks illustrated by his own photographs (which are also featured in "Spalding's Winter Sports") and even film reels. You can read a more extensive biography of him below. AuthorJames A. Cruikshank was an expert on outdoors sports during the first half of the 20th century. Born in Scotland but spending most of his life in New York, he was the editor of The American Angler magazine, Field and Stream, and wrote numerous articles for a wide variety of other magazines and newspapers throughout his career, including the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. He also published at least three books: Spalding’s Winter Sports (1913, 1917), Canoeing and Camping (1915), and Figure Skating for Women (1921, 1922). He also contributed a chapter on artificial lures to The Basses: Freshwater and Marine (1905). In addition to his writing, Cruikshank was involved in public speaking, doing talks on outdoor sports sometimes illustrated by motion pictures. An avid photographer, Cruikshank’s photos often featured in his illustrated lectures, his articles, and his books, as he encouraged readers to take their own cameras out-of-doors. He had a home in the Catskills as well as a home and offices in New York City, and in the 1930s he helped found the Hudson River Yachting Association. At one point, he managed the Rockefeller Center ice skating rink, and another in Rye, NY. His wife Alice was also an avid camper and hiker, and they often traveled together. In 1909, Alice went “viral” in newspapers around the country by being the first person to blaze a trail between Mount Field and Mount Wiley in the White Mountains of New Hampshire (James brought up the rear). James and Alice eventually moved to Drexel, PA and were vacationing in Lake Placid in July of 1957 when James died unexpectedly at the age of 88. Stay tuned next week for the next chapter in Spalding's Winter Sports (1917)!

If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today! Editor’s Note: The following text is a verbatim transcription of an article featuring stories by Captain William O. Benson (1911-1986). Beginning in 1971, Benson, a retired tugboat captain, reminisced about his 40 years on the Hudson River in a regular column for the Kingston (NY) Freeman’s Sunday Tempo magazine. Captain Benson's articles were compiled and transcribed by HRMM volunteer Carl Mayer. See more of Captain Benson’s articles here. This article was originally published December 12, 1971. Back in the days before boatmen were unionized, steamboatmen would go to work as soon as the ice broke up in the spring and work continuously until their boat was layed up when the river froze over in December. In those days of long ago, almost all of the steamboats had wooden hulls and as soon as the river would freeze, all navigation would cease. The ice would raise havoc with those wooden hulls. New ice in particular was dangerous. It would be as sharp as a knife and as a steamboat went through the new ice, the ice would take the caulking right out of the seams and cause the hull to leak. When I was a deckhand on the tugboat “S. L. Crosby” of the Cornell Steamboat Company in 1930, I recall Harry Conley, the pilot, telling me about the time in the 1890’s when he was quartermaster on the “City of Troy,” one of the steamboats between New York and Troy. When the first snow of the season would come, the crew would be happy because they knew then that it wouldn’t be long before the ice would be forming and the “City of Troy” would be laying up for the winter. After the men had been working since early spring, with no time off, they would welcome their winter time vacation. He would tell me how with the first real cold snap, they would leave Troy and the crew would listen for the first sounds of fine ice forming. On a still, bitter cold, clear December night you can hear the snap and crackle of the new ice. It is a sound a boatman never forgets. Generally, the new ice would begin to first form in the river around Esopus Meadows Lighthouse. Then, the crew would be all smiles, knowing in a few days orders would come for the last trip of the season and the “City of Troy” and the crew would have a two or three months rest. The would go home, Harry to Schodack with about one hundred dollars saved from his wages and live real good. During the winter, most of them would work at one of the ice houses, harvesting the winter’s crop of ice. I still look forward to the first snow of the season, despite the fact today the tugboats all have steel hulls and many work all winter long. How different the river shores look all covered with the first snowfall. It seems like only yesterday the wild flowers and purple loose leaf were blooming all along the up river shore line. Now everything looks cold and bleak. With snow on the shores and hills, one can see paths going up from the river that you cannot see in the summer when the foliage is thick on the trees. Also houses and stone walls stand out in startling clarity. How a snow storm changes the landscape into a wonderland when the river becomes locked in winter’s cold embrace! The first snow storm also changes other things. A few years ago I remember leaving Coeymans right after the first snow. As we were leaving, my deckhand said, “Bill, this sure makes us think what we did with our summer earnings, doesn’t it?” AuthorCaptain William Odell Benson was a life-long resident of Sleightsburgh, N.Y., where he was born on March 17, 1911, the son of the late Albert and Ida Olson Benson. He served as captain of Callanan Company tugs including Peter Callanan, and Callanan No. 1 and was an early member of the Hudson River Maritime Museum. He retained, and shared, lifelong memories of incidents and anecdotes along the Hudson River. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

On Saturday we featured a historic wooden sign from the Newburgh Ferry Terminal. Today, for Media Monday, we're sharing some stories from the ferry.

This first story, from the Sound & Story Project, tells of what happened when the ferry encountered some ice.

To hear what the ferry might have sounded like traveling through the ice, check out this historic recording from Conrad Milster, who recorded the ferry Dutchess traveling through the ice.

The Newburgh-Beacon ferry ceased operation in 1963 with the opening of the Newburgh-Beacon Bridge, but was revived in 2006 as a commuter ferry for residents traveling to the Beacon train station.

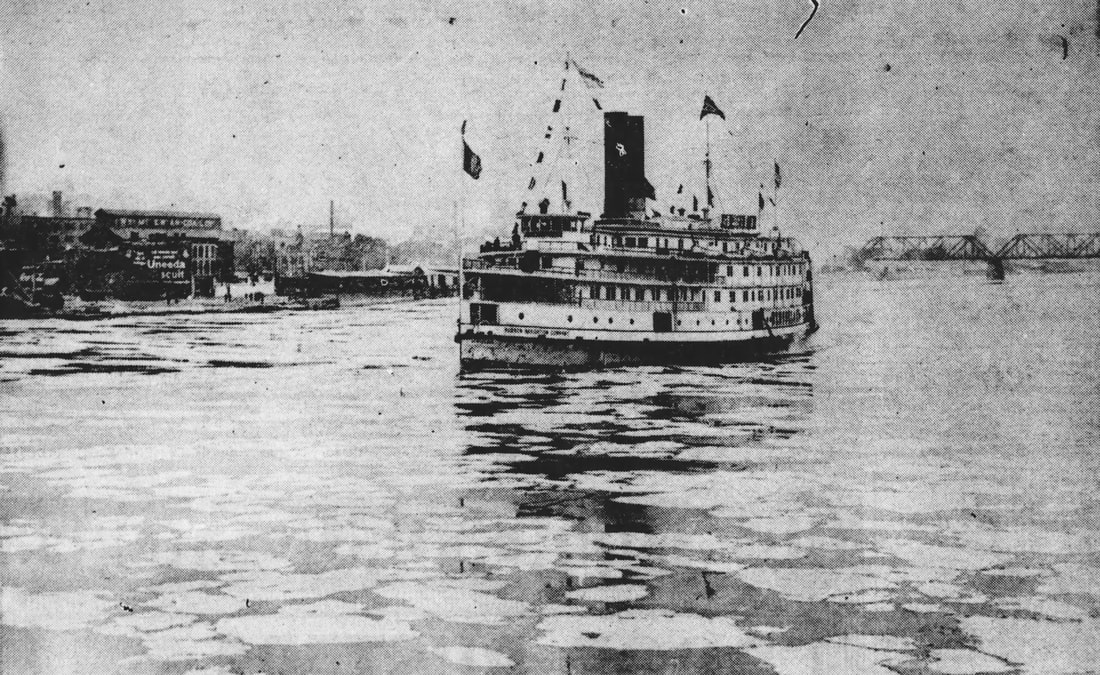

Have you ever traveled on the Newburgh-Beacon ferry, either the original or the new one? Tell us about your experiences in the comments! Editor’s Note: The following text is a verbatim transcription of an article featuring stories by Captain William O. Benson (1911-1986). Beginning in 1971, Benson, a retired tugboat captain, reminisced about his 40 years on the Hudson River in a regular column for the Kingston (NY) Freeman’s Sunday Tempo magazine. Captain Benson's articles were compiled and transcribed by HRMM volunteer Carl Mayer. See more of Captain Benson’s articles here. This article was originally published February 18, 1973.  "THE STEAMBOAT “RENSSELAER” PASSES ALBANY on Jan. 29, 1913, the date of her mid-winter excursion. Although her flags and pennants are flying in mid-summer fashion, the floating ice in the Hudson and the very few people in deck testify to the frigid temperatures." Image originally published with article, February 18, 1973. In days gone by, steamboat excursions were commonplace. Almost without exception, they were offered during the summer and occasionally in the late spring or early autumn. One highly unusual excursion - probably the only one of its type - took place in the dead of winter on Sunday, Jan. 29, 1913. On that winter’s Sunday, the steamboat “Rensselaer” of the Hudson Navigation Company was chartered for an excursion by the Troy Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks, No. 141. From Troy down the river to Hudson and return. The story of that long ago excursion was related to me by the late Francis “Dick” Chapman of New Baltimore, one of the pilots of the “Rensselaer” the day of that wintry sail on the river. Dick said the sky was overcast, and it was a day when the cold “would penetrate right to your bones.” About 10 a.m. it started to snow and the river was full of floating cakes of ice. They were scheduled to leave Troy at 12:30 p.m. On the way down river, they were held up briefly at the first railroad drawbridge by a crossing freight train. When the bridge opened and the “Rensselaer” got in the draw, she lay there until the Maiden Lane Bridge, downstream, opened. She eventually passed the Night Line dock at Albany at 1:45 p.m. Down at Van Wies Point, below Albany, the river was covered with ice from shore to shore and the “Rensselaer” had to make a new channel. As she was going through the ice her paddle wheels would throw the ice up against the steel lining of her wheel batteries. It sounded like crashing thunder. One could hear the noise all through the streamer. Although they were originally scheduled to go down river as far as Hudson, Dick told me the visibility was so poor and the ice so heavy, they decided to go only as far as Castleton. There, they turned around and went back up river to Troy. They steamed slowly on the return so as to give the Elks their full time afloat. Since the visibility left much to be desired, it was somewhat questionable if the excursionists would have been able to see any more of the river if they had gone all the way on to Hudson. A few years later, the Night Line decided to try and operate year round service. The “Rensselaer” and her sister steamer “Trojan” were chosen for the operation. On one of the “Rensselaer’s” trips down river, she was passing a Cornell tow fast in the ice off Germantown. When the “Rensselaer” tried to pull out of the tracker and break into the solid ice to pass the tow, she sheared off right into the tow. The Cornell helper tug “George W. Pratt” - laying alongside the tow - couldn’t get out of the way and the guard of the “Rensselaer,” before they could get her stopped, went over the rail of the “Pratt” and shifted and damaged her deck house. With damages like that to the “Pratt,” and - after every trip - having to make repairs to the paddle wheel buckets and required to put new bushings in the arms of the feathering paddle wheels, the Night Line soon found the project to be too costly. Side wheel steamboats were just impractical for operation in the ice. During that short period when the “Rensselaer” and “Trojan” attempted to operate during the winter, old boatmen told me on a clear, cold night they could hear the “Rensselaer” or “Trojan” at Port Ewen when the steamers were up around Barrytown or on the up trip, as far away as Esopus Island. They would hear their paddle wheel pounding and breaking the ice and crashing the broken ice cakes against the steel paddle wheel housings. The captains and pilots of the night steamers on the river deserved a tremendous amount of credit for their skill in operating those old side wheelers in all kinds of weather. Unlike the captains and pilots of the day steamers that usually operated during the daylight in the best months of the year, the night boats would run from early spring to late fall and encounter lots of fog, snow or whatever came their way. The upper end of the Hudson in particular is very narrow, and the night boat men always had tows, yachts, and floating derricks and dredges to content with. Regardless of the weather, almost always they would bring their big steamboats into Albany on time. Those captains and pilots were, as they say, “right on the button.” The “Rensselaer” and the “Trojan” were cases in point. From the time they entered service in 1909 until the end of their service in the latter 1930’s, they rarely had a mishap. Probably the most serious mishap to the “Rensselaer” occurred on Sept. 27, 1833 when she was in a collision with an ocean freighter off Poughkeepsie. This incident will be the subject of a later article. AuthorCaptain William Odell Benson was a life-long resident of Sleightsburgh, N.Y., where he was born on March 17, 1911, the son of the late Albert and Ida Olson Benson. He served as captain of Callanan Company tugs including Peter Callanan, and Callanan No. 1 and was an early member of the Hudson River Maritime Museum. He retained, and shared, lifelong memories of incidents and anecdotes along the Hudson River. Editor’s Note: The following text is a verbatim transcription of an article featuring stories by Captain William O. Benson (1911-1986). Beginning in 1971, Benson, a retired tugboat captain, reminisced about his 40 years on the Hudson River in a regular column for the Kingston (NY) Freeman’s Sunday Tempo magazine. Captain Benson's articles were compiled and transcribed by HRMM volunteer Carl Mayer. See more of Captain Benson’s articles here. This article was originally published January 23, 1972. For a number of years prior to World War I, the Hudson River Day Line always layed up the “Mary Powell” and the “Albany’’ for the winter at the Sunflower Dock at Sleightsburgh on Rondout Creek. At that time, Mr. Eben E. Olcott was president of the Day Line. During the winter of 1917, both the ‘Powell’’ and the ‘Albany’ were, as usual, layed up at the Sunflower Dock. Across the creek on the Rondout side, both Donovan and Feeney had boat yards. Both shipyards had built canal barges and launched them in the ice. Also, they were loading the new barges with ice to ship to New York when navigation opened again in the spring. And, where they had taken in the ice, there were various channels cut in a multiplicity of different ways. Anybody not knowing this and trying to walk over the ice at night would be necessarily taking his life in his own hands. Snow and Sleet On the night I am writing about, it started to snow and sleet about 6 p.m. And, at that time, Phil Maines of Rondout was the ship keeper on the ‘‘Mary Powell.” About 11 p.m. Phil thought he would take a walk around to see if everything was all right before taking a nap. As he started up the companionway, he thought he heard someone walking on the deck above and trying to open the doors. He knew he had left one door unlocked, so he went up on deck and stood in the dark behind the unlocked door, waiting for whoever it was to come in. After a while the door slid back and a man walked in. Phil, standing in the dark, said, “Stick up your hands! Who’s there?” The reply came back swiftly, “It’s Mr. Olcott, Phil, only me. I thought I’d drop around and see if everything was all right.” He was Lonesome So, together, they went down to the winter kitchen, which was on the main deck for the keeper’s use in winter, and had a cup of coffee. Mr. Olcott said he was staying over night in Kingston, had gotten a little lonesome and so thought he would come over and see Phil for awhile. After he had stayed for about 15 minutes, he said he was tired and thought he’d go back to his hotel and get some rest before morning. Phil took him back across the creek, this time with a lantern. How Mr. Olcott ever got over to the “Powell” without falling through the ice in the many ice channels was not only a streak of good luck for the president of the Hudson River Day Line, but something of a miracle in itself. AuthorCaptain William Odell Benson was a life-long resident of Sleightsburgh, N.Y., where he was born on March 17, 1911, the son of the late Albert and Ida Olson Benson. He served as captain of Callanan Company tugs including Peter Callanan, and Callanan No. 1 and was an early member of the Hudson River Maritime Museum. He retained, and shared, lifelong memories of incidents and anecdotes along the Hudson River.  Two early automobiles pause on the ice of the frozen Hudson River in front of the Tarrytown lighthouse. Fred Koenig and Bob Hopkins in one car and a Mr. Maxwell and Mr. Chadwick in the other were racing to Albany. They had to turn back at Newburgh because the Newburgh-Beacon ferry kept the channel open. Hook Mountain is visible in the background. 1912. Courtesy John Scott Collection, Nyack Library. In the early days of automobiles, speed demons were not content with ice yachts, and tried their luck on the frozen Hudson with autos instead. On January 28, 1912, Robert E. Hopkins drove his automobile from Tarrytown to the Tarrytown Lighthouse (today known as the Sleepy Hollow Lighthouse). This was before General Motors filled in all but 100 feet of water to the lighthouse, so this was quite the distance. According to the New York Times, "The feat had never been attempted before." Robert E. Hopkins was the son of Robert E. Hopkins, Sr., who had supposedly "made millions in oil." Hopkins wasn't alone on the ice that day - plenty of people were out skating, on horseback, and even in automobiles, but most stuck close to shore, where the ice was more reliable. Just a few days later, on February 3, 1912, Fred Koenig in his Mercedes and raced against M.R. Beltzhoover's Mercer in a 25 mile route on the ice off of Tarrytown. Koenig won that race by two laps, but Beltzhoover won the three mile straightaway race from the Tarrytown lighthouse to the Tarrytown Boat Club docks. Other auto races also gave speed exhibitions, and Beltzhoover got his Mercer up to 75 mph. The ice was "in fine condition," so arrangements were made "for a bit automobile meet next week." Despite these recreational activities closer to shore, the main shipping channel was still open - being kept clear by icebreaking tugs. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Rockland Lake, near the Hudson River about 25 miles north of New York City, was the largest natural ice harvesting operation of the Knickerbocker Ice Company, which was the most prominent ice purveyor at the turn of the 20th Century, when these Thomas Edison films were shot. The three ice houses stored close to 100,000 tons of ice, which were loaded onto barges that made their way down the Hudson to New York City. Today, Rockland Lake is a New York State Park, and the home of the Knickerbocker Ice Festival. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's Note: This account is from the February 23, 1879 New York Times. The tone of the article reflects the time period in which it was written. "A Winter Ramble Over The Surface of the Hudson – Fishing Through The Ice – A Trap for Ice-Yachts – Trying Speed With Thought – Looking Down Upon A Winter Scene Walking on the surface of the deep is no miracle in our climate. But the experience is quite rare enough to make a vivid impression, especially on those who tread habitually the dull sidewalks of a city. For the mind is haunted by at least a feeling of the miraculous as you walk over a great lake or river. The elements seem to have forgotten their laws, and the whole face of nature is weird when her gleaming eyes turn glassy. This unusual view of nature drew me to visit the Winter scenes on the Hudson. I purposed on this Winter walk to go from Poughkeepsie to Newburg on the ice, through the region renowned for ice-boating; where they hold tournaments for lady skaters; where they trot horses when they cannot row regattas; and where Winter life on the ice may seen in its perfection. I started by skating, and I rested from this by sailing, and walking part of the time, for I have a friend on the way who is a famous iceboat skipper; and we skipped about the river with the speed of the wind. I can scarcely call the trip a walk; for I traveled neither all by water nor by land, nor yet as the fowls of the air. But, however I went, the excursion was delightful with scenes and experiences characteristic of the Winter life of the Hudson. As I left the dock at Poughkeepsie and skated out over the river, a thrill – almost a shiver – ran through me as I thought of the depths. But a few inches below my feet. Of course, one is not afraid on ice nearly a foot thick, but this unusual relation to deep wide water is unavoidably startling. You say to yourself there is no danger, but you feel to yourself, this is all very queer. The first minutes of my trip were therefore a little chaotic, with the confidence born of other people’s opinions, yet, with my own secret questioning about the ice all the way down my long route. But the exhilaration of the keen Winter morning soon bore away every other feeling. The thermometer marked only 15 degrees; a light west wind blew down over the hills of Ulster County, and the clear air and sunlight made the most distant scenes appear like faultless miniatures. I looked down the river 20 miles, over my whole route. The river near by was a narrow level valley between high banks of bare trees. The hills over-topping the banks were also brown and bare, excepting here and there a patch of snow or a knoll crowned with cedars that added deep shadows to the sober face of nature. The level valley of ice ran straight away to the distance between dark wooded headlands projecting one behind another, and marking in clear perspective the long vista of the river. The valley seemed to end at the foot of the Highlands, which over-topped the whole scene with their majestic heads, now gray with snow under a bare forest. This long level of ice was generally smooth, excepting here and there, a low wandering ridge of projecting edges and cakes at cracks; and the shores were marked by a tide. Groups of men and boys were seen down the valley, even far off, and a few ice-boats were moving about at Milton, four miles below, and at New-Hamburg, 10 miles off. The mirage was very strong this clear morning, so the boats appeared double, as if one ran on the ice and other under it. The new ice was a curious record of nature in a warm and lenient hour. Jack Frost seemed a tell-tale of his freaks. He had pressed her white flowers; he had preserved her little landscapes modeled in the ice of rivulet, gorge, and bluff; he had caught the wind playing with the ripples and locked them fast, and he had painted the clouds and scattered crystals for the stars. I soon reached Blue Point, where some fishermen were taking up their nets, and a few boys were grouped about them. Two men at each end of a narrow trench cut through the ice, and hauled up a line. These lines at last brought up a net 12 feet square, with a pole across the bottom, weighted with a stone at each end. The nets are lowered her about 50 feet, or half way to the bottom, and 10 to 20 of them are put down in a row across the current, over a reef or rocky point. The upper ends of the lines are tied to sticks that lie across the open trench, or stand up in the ice. The nets swing off under the ice, by the pressure of the current, and fill out like open bags. Catfish run into them, and are kept there by the current until slack water enables them to leave; but perch and bass are caught by the gills in the two-and-a-quarter-inch meshes. When the nets had all been lifted and put down again, the men picked up the few perch and young sturgeons, frozen as stiff as sticks, and walked to the shore. There they had a flat-boat decked over for a house. Bunks, stove, and various fishing-tackle filled the little cabin with a chaotic mass. They will launch their boat when the ice leaves, and float up or down then river as inclination may direct. In good seasons this ice-fishing yields often 50 pounds of fish at a lift, the men make about $10 per day with 20 nets. This year the fishing here is very poor, for the great freshet of the Fall carried the bass down to Haverstraw Bay. I left the fishermen of Blue Point, and skated down the opposite shore. The bluffs along the railroad cuts were hung with great icicles, some of them 8 or 10 feet long. Every projecting ledge of some cliffs, from top to bottom, was decked with these splendid crystals, flashing in the sunlight. And at their feet, the twigs and rocks were covered with round forms of quaint shapes. While I stood there the rails began to ring faintly, but clearly as a bell, in the frosty air. The sounds beat in quick pulsations, grew to a rumbling, then to an increasing roar, and in a moment an express train came around the point at a thundering pace. All the stillness and peace of the morning vanished as before the blast of war. It passed in an instant; the roaring fled; the rails rang again with a clear, pure music, softer, and fainter still, and then the Winter silence came once more over the valley of ice. The solemn repose of the great river was then unbroken. For even its mutterings were solemn, when the ice cracked under my feet with a loud report, and the sound darted away in quick, erratic angles to the bluff, and still rumbled on in persistent gloom. The falls at the Pin Factor were a scene of prettier details. The rocks were covered with pillowy masses of whitish ice, and the clear water came down in zig-zag courses, now over these pillows, now under ice caverns built over rocks. The steep descent of the stream was guarded by rustic balustrades of roots and branches, all covered with ice, and the whole was partly veiled by some bare elms, bushes, and dark cedars. A nearer view of the ice showed it to be a bank of crystal flowers, gleaming faintly with prismatic hues in the sunshine. The water ran all over it in little rivulets perfectly free from earthly stain. The dim caves were the most poetic objects; they had neither a ray of sunshine nor a line of shadow within them; yet their sculptured walls were exquisitely shaded with the softest, clearest lights, and the arch in front was hung with crystals of brilliant colors. The whole fall was full of magic, the faint Winter music of the stream, the exquisite delicacy of forms petrified as in death, and the strangeness of objects that transmit light instead of casting shadows. The only witness of the scene is an old mill with a crumbling wheel that once turned round to the music of the brook. Now when the moonlight shines on his tottering form on the falls in the magic of Winter, and on the wide river groaning in his bed, the scene must be still more weird, if not more beautiful. I went on to Milton, and there found my friend and his ice-boat ready for a cruise further down the river. I put on a few suits of clothes, woolen socks, arctics and mittens; then we embarked, and glided away toward New Hamburg. Other boats were skimming over the ice, and we exchanged many social greetings, if that term can be applied to salutations that begin and end at opposite points of the horizon. I dream of flying when I hold the tiller of an ice-boat, and find myself flitting about the earth, and reaching a place almost as soon as my thought of it. We flew about the Hudson for an hour or more, here turning to visit this point or that, there pausing in our flight to enjoy the excitement of another start, or to touch the social scenes and incidents of this Winter life. At a place near Milton we were admiring a large boat coming from the distance at great speed. Suddenly she stopped. As something was evidently the matter, we ran down there, and found her fast in a hollow that had been filled with water and then skimmed with thin ice. These hollows form by the expansion of the ice. The expansion across the river drives the ice up the shore, so that no cracks form up and down the stream. But the still greater expansion of the long stretches of ice up and down the river find no such room as the shores. The ice, therefore, doubles up, or buckles. It thus either throws up a low ridge, or else forms a hollow, on each side of the cracks running across the stream. The ridge does not interfere much with travel until one side of it drops down and makes a step or fault. But the hollow fills with water, sometimes several feet deep; and at last the tide catches one side of the inclined cakes or sides of the hollow, doubles it under, and carries it away. These clear, open cracks, from 10 to 20 feet wide, are slow to freeze, and generally offer the most dangerous places on the ice. They may form at any time, even in cold weather; so that constant attention and good light are required in raveling up or down the river. But, to return to the stranded ice-boat. She had a good breeze, and had come to this hollow too suddenly to avoid it. If the new ice had been a little stronger, or else narrower, it might have held her up till her forward runners had reached the old ice on the further side of the hollow, and the high wind, with her momentum, would have drive her through. This she would have “jumped a crack,” as the phrase goes; instead of this she “broke through,” as another phrase goes, and her passengers and crew were there surrounded by broken thin ice over a hollow of water in a depression of old ice. Now, we were interested chiefly in the passengers, for they were two very pretty girls, who explained with much animation and distinctness that they would like to get out of that situation. They appeared very well in the midst of rich furs and robes, but for once this advantage was ignored. So we had all the pleasure of their unnecessary distress, and finally landed them, still warm and dry, on the old ice. Then the boat was rescued, and amid many thanks on one side and some merry advice on the other, both parties darted away on the wind. We were afterward favored with pretty salutations from them, too literally en passant, yet too long drawn out for any comfort. Afterward, the same hollow entrapped a second boat; but this had only men aboard and we let them scramble out by themselves. A third boat came up to see what was the matter, and also ran into the trap. Then a fourth came up with a gust of wind, and ran her port runner and the rudder in before she could be rounded to. The water flew, the ice rattled; and it came so suddenly that the whole crew jumped off in a fright. But the whole crew was only one man, and the helmsman stuck to his tiller and brought her out to clear sailing again. At Marlboro we found a crowd of skaters and sliders, collected to witness a horse-race on the ice. They all seemed to be animated with red, red noses. For the wind was keen, and they had to keep in constant motion. Some rosy girls and boys, with scarlet mittens and comforters, were skating hand in hand along the retired nooks of the shores. And some of the farmers from the hills were speeding their horses up and down the straight track on the ice. The village looked down on the scene from the head of its picturesque ravine. Northward, the river stretched away between its bold banks to Poughkeepsie, throwing up a cloud of thin smoke on the Western wind. Southward, the valley of ice ran between still bolder heads of dark cedars, along the sweeps of Low Point, past Newburg, and down to the foot of the Highlands. The gray heads of the mountains were nearer and grander now than when I first saw them from up the river. As the afternoon was passing away, we had to turn our backs on the swarms of boys and men at the horse-race, wave a last farewell to our pretty acquaintances on the ice-boat, and stand away southward. We flew along with a stiff breeze past New-Hamburg, the bold hills at Hampton, and on to other picturesque points. Cracks in the ice here and there made us turn in and out, and flit about with the quick motions of a bird. At last I had to give up the tiller, at the Dantz Kammer Point, shed my various suits down to a walking load, and bid the skipper good by as he flew away up the river. But, after all, give me the sober earth for better or for worse. I enjoyed again the firmness of a good hard road, and the steadfast reality of a good walk down to Newburg. The road gradually mounts the high bank of the river among an army of cedars storming the height, and some farm-houses and orchards in their Winter reserve. At the top of the hill, near Balmville, you look back up the river and over the plains of Dutchess County. Southward the view includes the rolling hills about Newburg and Fishkill, the spires of these pretty towns, and the broad bay between them. The valley of ice contracts there to enter the magnificent gorge of the Highlands, and then disappears behind the shoulders of the mountains. These majestic spirits of the Winter scene are now still grander as you near their feet and gaze at their hoary, silent crowns. The suburbs of Newburg were quite cheerful. Carriages, with spirited horses, and with rosy faces above rich robes, dashed along the roads, and here and there a cozy home-scene shone out of window among evergreens. The town, too, was alive with teams and people from the surrounding country. Winter vigor and high spirits pervaded both man and beast. And I was kin enough to each to share in their joy for the keen Winter day. C.H. F." AuthorThank you to Hudson River Maritime Museum volunteer George Thompson, retired New York University reference librarian, for sharing these glimpses into early life in the Hudson Valley. And to the dedicated museum volunteers who transcribe these articles. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

|

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 info@hrmm.org Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |