History Blog

|

|

|

|

|

March is a good time to celebrate the Irish cultural and historical heritage of the Catskill Mountains. What had been fondly called “Ireland’s 33rd County,” the Irish Alps, or Irish Catskills, was the prime summer destination for thousands of Irish immigrants living in the dense cultural neighborhoods of New York City. Many would take refuge in the lush, rolling green hills of the Catskills away from the heat and dust of NYC summers. Whether by bus, train, or car, hundreds of Irish New Yorkers would make the annual trip to the Catskill Mountains from the 1920s to the early 1970s. The PBS documentary, “The Irish Catskills: Dancing at the Crossroads,” referenced for this blog post, takes viewers on a tour of not only Irish cultural heritage but a sweeping history of the annual migration of Irish-American families to keystone towns of the Irish Catskills, like East Durham, Leeds, and South Cairo. The Catskill Mountains became synonymous with summertime and the leisure of the middle and upper classes by circuitous means. According to Michele Herrmann, writer of “The Borscht Belt Was a Haven for Generations of Jewish Americans,” for Smithsonian Magazine, Jewish aid societies in New York created programs that encouraged Jewish immigrants to earn a living via agriculture as a way of supporting Jewish communities in the States. The Catskill Mountains, however luscious in its greenery, are not conducive to farming given their rocky terrain. New inhabitants of the area quickly learned that they were better off using the land to attract borders for the summer months. The mountains were a major draw for New Yorkers, initially, as doctors at the time often advised tuberculosis patients to get fresh mountain air and (literal) breathing room; the disease was easily contracted in the tightly packed neighborhoods and tenement houses of New York City. Advertising also helped direct attention to the Catskills’ resorts and hotels, such as the guidebook series “Summer Homes” published by New York and Ontario Railway. As Herrmann writes, “...one Jewish farmer named Yana “John” Gerson listed one of the publication’s first advertisements for a Jewish boarding house in the 1890s.” As tens of thousands of Irish immigrants made their way to the United States, they sought a lucrative opportunity to renovate old barns and boarding houses (previously owned by German immigrants up until World War II) into modest hotels for the typical urbanite looking for the fresh mountain air of upstate New York. Many Irish immigrants were also motivated by homesickness, and sought out the familiar surroundings, familiar accents and cultures that made home not feel so far away. The Irish Echo, the oldest Irish-American Newspaper in the United States, established in 1928, and later the Irish Voice were written for Irish audiences, as well as word of mouth, may have advertised these Irish-founded bars, restaurants and hotels bolstered the weary Irish-American city-dweller to explore upstate New York. Hotels like O’Neill’s Cozy Corner in East Durham, NY, later named The O’Neill House, were among the first Irish-owned establishments in the area and sported the latest trends in hotel hospitality. Far more humble than the free wi-fi and complimentary gym access that are the bare minimum of hotel standards today, hotels in the 1920s and 1930s were still writing the “blueprint” that the hospitality industry uses today. A top choice hotel like O’Neill’s Cozy Corner would include such amenities as private toilets, hot and cold running water, electric lights, and East Durham’s first concrete swimming pool. Converted barns acted as dance halls for patrons who would dance along to the musical styles of famous Irish musicians living in New York City who would come up to East Durham and play traditional Irish music. A fun night out in the Irish Catskills would be incomplete if it didn’t have “Stack of Barley/ Little Stack of Wheat,” playing at least a few times that evening. The newfound leisure of the working class came on the heels of harsh working conditions of Irish transit workers in New York City, who worked primarily in subway, bus and railroad industries. At this time in American history, there were no laws that dictated the quality of working conditions or for how long people worked or whether or not they were allowed to take time off, so work hours depended upon the generosity of one’s boss, who was usually not very generous. It was common for a transit worker to have 12 hours-long, grueling shifts, every single day with no vacation time. In fact, transit workers were regularly fired for taking off on a Sunday to go to church. That is, until Michael J. Quill, from County Kerry in Ireland, co-founded the Transit Workers Union of America in 1934. He advocated on behalf of over 34,000 transit workers for higher wages, a 40-hour work week, and paid vacation time. These changes introduced leisure time to the lives of many transit workers and their families. With higher wages and paid vacation time, Irish families could now afford to travel and stay at resorts and hotels for extended periods of time. Predominantly working class families could now experience rest and what it felt like to be waited on for a change. Of the over 40 Irish-owned hotels and resorts in the Catskills at the height of their popularity, only a handful are in business today. As one contributor reflects in “The Irish Catskills” documentary, “Air conditioning, airlines, and assimilation were the three A’s that killed the Catskills.” As the 1960s and 70s came to a close, the majority of Irish immigrants were no longer working class but were upper middle class. They could not afford the luxury of their own backyards and larger homes that made escaping to the mountains redundant. When the Irish Catskills first came into prominence, most immigrants could not afford to go back home to Ireland, which is what made resort life in the Catskills feel so welcoming. Around the time of the Catskills’ decline in popularity, upper middle class Irish-American families could afford to travel to the real Ireland whenever they wanted, so an analogue of Ireland was no longer necessary. Air conditioning went from a luxury to a summertime necessity, so spending one’s free time in a hot wooden cabin in the middle of the woods was no longer as appealing as it once had been. However, there are places in upstate New York that are doing their part to keep the Irish musical and cultural history of the Catskills alive. Shamrock House, an inn/restaurant/bar holds Traditional Irish Sessions every Sunday afternoon, in which musicians can bring their own instruments and play alongside each other, or simply come and be a joyful spectator. Annual events like Irish Arts Week have also taken on the mantle of maintaining Irish traditional music and dance for the next generation of young artists. Each summer, famous musicians teach middle school and high school aged kids the traditions and cultures that have become synonymous with the Catskills Mountains and Irish communities abroad. External Links: To watch the full “Irish Catskills” documentary: WMHT Specials | The Irish Catskills: Dancing at the Crossroads | PBS

AuthorCarissa Scantlebury is a volunteer researcher at the Hudson River Maritime Museum. She graduated from Hunter College with a degree in Classical Archaeology. She loves getting lost in a cozy fantasy novel, watching Doctor Who (David Tennant is her favorite), and learning new languages. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

0 Comments

Our friends at the Mariner's Mirror podcast have featured another Hudson River story! Dr. Marika Plater first wrote about the use of steamboat excursions by Chinese Americans here on the History Blog back in October of last year. Here, she discusses her research with Mariner's Mirror podcast host, historian, and author Dr. Sam Willis.

Listen below or on the Mariner's Mirror podcast website.

If you missed the first HRMM interview on Mariner's Mirror with Director of Exhibits & Outreach Sarah Wassberg Johnson, you can listen here.

On a bright June morning in 1883, a boat flying the red and yellow Chinese flag left a pier in lower Manhattan and steamed up the Hudson River. Onboard were hundreds of Chinese American men who attended missionary Sunday Schools. Though most of these adult pupils worked for low wages in steam laundries that mechanized the washing of clothes, they had saved their pennies to organize a getaway for the white women who taught them how to speak English and read the Bible. Through telescopes and opera glasses, students and their teachers watched from the deck of the steamer as city turned to mountains, wetlands, forests, and meadows.[1] After a journey of almost fifty miles, the party landed at Iona Island to explore hundreds of acres of woodland, grassy lawn, salt marsh, and an abandoned vineyard.[2] “Frantic with excitement,” the Chinese American students “immediately set off quantities of fireworks” that turned “the atmosphere of the island blue,” according to the New York Times. As smoke and sparks shaped like “dragons, serpents, and birds of different species” filled the air, the smell of gunpowder masked the salty sea breeze.[3] After a day spent listening to music, resting in the shade, flying kites, picnicking, and praying, the party embarked for home in the late afternoon.[4] This was one of many steamboat excursions that exposed the city’s working people to the wilder places outside New York in the late nineteenth century. All excursionists shared the desire to see gorgeous scenery, relax and recover from a relentless work schedule, and breathe air that was much fresher than what could be found on the crowded and unsanitary streets of Manhattan. But excursions had extra layers of meaning for Chinese Americans during the era of Chinese Exclusion. The excursion to Iona Island took place in 1883, the year after U.S. legislators passed the first Chinese Exclusion Act in the context of rising anti-Chinese xenophobia. For more than a decade, white workers had been condemning immigrants from China, framing boatloads of hungry newcomers as ruthless competitors whose willingness to labor for low wages would push others out of work. The following horrifically racist cartoon reflects this fear, blaming people of Chinese descent for low pay and job scarcity in the United States.  This racist cartoon suggests that Chinese laborers, depicted through dehumanizing caricature, would monopolize jobs that should go to white workers. George Frederick Keller, “What Shall We Do With Our Boys,” The San Francisco Illustrated Wasp, March 3, 1882, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:What_Shall_We_Do_with_Our_Boys,_by_George_Frederick_Keller,_published_in_The_Wasp_on_March_3,_1882_-_Oakland_Museum_of_California_-_DSC05171.JPG Race drew a perceived line between worthy workers and harmful outsiders. Newcomers from Europe arrived in much higher numbers, but those from China faced extra blame and condemnation. Three hundred German American protesters who gathered in New York’s Tompkins Square in 1870 cheered as a labor leader condemned “the lowest and most degraded of the Chinese barbaric race” for taking jobs away from white immigrants.[5] Nativist fearmongering overshadowed the culpability of greedy employers, who drove down wages knowing that there would always be someone desperate enough to accept less pay. What made laborers replaceable, furthermore, was the mechanization of production that eliminated the need for extensive job training. Immigrants of Chinese descent were scapegoats during a complex transition to industrial capitalism. This prejudice became policy in 1882, when the Chinese Exclusion Act banned Chinese laborers from entering the United States.[6] The excursion to Iona Island that took place the next year pushed back against the Chinese Exclusion Act. The strategic guest list suggests that the getaway was about politics as much as play. Organizer Der Ah Wing invited prominent Chinese Americans to join the Sunday school students and their teachers, like editor of the Chinese American newspaper Wong Chin Foo and Chinese Consul Au Yang Ming. White guests included Postmaster Henry Pearson, who managed the delivery of mail from China, and merchant Vernon Seaman, who spoke Chinese and was an advocate against exclusion.[7] Also onboard was Customs House Collector William Robertson, who enforced the Chinese Exclusion Act as the manager of New York’s port. Robertson shared the deck with a man he had detained: Professor Shin Chin Sun, who arrived without the proper paperwork to prove that he was not a laborer banned from entry to the country.[8] The excursion set the stage for influential men from opposing sides of the nativist law to meet one another and engage in potentially transformative conversations onboard the steamboat and in the leafy grove at Iona Island. The Sunday School excursion furthermore pushed a story of friendship between people of Chinese and European descent into public view, countering the pervasive narrative of conflict and competition. Newspapers reported that “American ladies and Chinese gentlemen were chatting affably together, Chinese boys were playing with American children, and the language of America and China mingled in conversation.”[9] Harper’s Magazine printed the following image of students and their teachers listening to music and flying kites together at Iona Island. While the white women’s faces are drawn more carefully, the Chinese American men are depicted here with much more respect than in the cartoon above. The friendly relationships that the excursion showcased likely shaped this media coverage that was much less dehumanizing towards people of Chinese descent than was usual for the time. The excursion taught some onlookers that people of Chinese descent could assimilate into New York’s general population. The Times framed the excursion as proof of “the civilization of American-resident Chinamen,” drawing on the racist framework that cast non-Westerners as uncivilized, but also breaking from stereotypes of Chinese Americans as permanent outsiders.[10] As other newspapers reported on the prayers and religious songs that excursionists sang together, Christian readers learned that they shared more with some of their Chinese American neighbors than they might have assumed. The excursion to Iona Island made similarities and amity between New Yorkers of Chinese and European descent visible at a tense moment when many whites argued that immigrants from China were too different to become Americans. Excursions became an annual tradition for Sunday schools because these getaways offered not just fun and relaxation away from the city, but also opportunities to shift ideas about Chinese Americans.[11] As journalist Wong Chin Foo covered the Iona Island excursion, he recognized the power of the event. But Wong was not a Christian. In 1888, he joined with fellow members of the Knee Hop Hong mutual aid society to organize what he called a “heathen picnic” for “the anti-Christian element of the Chinese.”[12] This excursion, which landed at Staten Island’s Bay Cliff Grove, also pushed against anti-Chinese nativism—but from another angle. While the Sunday School excursion drew attention to Chinese immigrants who converted to Christianity, members of the Knee Hop Hong were proud “joss worshippers,” according to Wong, who held fast to their beliefs.[13] The Knee Hop Hong excursion rejected cultural assimilationism too. While Sunday school excursionists drank coffee and ate what the Brooklyn Daily Eagle called “American dishes,” those on the Knee Hop Hong excursion toasted with “sparkling Noi Mai Dul” and ate chow chop suey.[14] Some smoked opium, a drug that was becoming increasingly taboo as prejudice towards Chinese people and culture mounted.[15] Excursionists indulged in Chinese American food, drink, and drugs as they celebrated what Wong called “the Birthday of Chinatown,” or the “founding of the New York colony.”[16] By praising the neighborhood where Chinese culture flourished, members of the Knee Hop Hong insisted that people of Chinese descent belonged in New York whether or not they assimilated.[17] The Knee Hop Hong excursion displayed the political and economic influence of Chinese American New Yorkers.[18] Decked out in diamonds, the organization’s president Tom Lee was a prospective alderman who reaped riches from Chinatown’s gambling halls and opium dens.[19] Also aboard were the neighborhood’s prominent merchants and Gon Hor, the grand master of the Chinese Free Masons.[20] Only “a small number of tickets,” Wong explained, were given to whites, “who must come well recommended as to character.”[21] While the Sunday school excursion showcased paternalistic relationships between white missionaries and their Chinese students and included an enemy who enforced the nativist law, the Knee Hop Hong made it clear that the only whites welcome aboard were demonstrated friends and collaborators. Chinese Americans had power of their own making, organizers of the excursion seemed to say, and owed no one deference. Once the party reached its destination in Staten Island, the crowd of at least 400 people listened to what Wong called “patriotic speeches,” given in both English and Chinese, that denounced exclusion.[22] JC Baptize asserted that “Chinese immigration was restricted by the politicians lest the Aldermen lose their jobs and a Chinaman be elected President of the United States.”[23] In his speech, Wong praised “the prosperity of the Chinese merchants, despite the opposition of Americans to them.”[24] The “prejudice of Americans” towards people of Chinese descent harmed the United States, Wong asserted, because “a grand result would be achieved if the moral and political virtues of the Chinese could be added to the enterprise and energy of the Americans.”[25] Insisting that immigrants from China enhanced the nation, speakers countered assumptions that their community was parasitic. Through their words and actions, these excursionists argued that they were worthy Americans because of, rather than despite, their Chinese roots. Yet newspapers stuck to hateful tropes when they covered the Knee Hop Hong excursion. The Sun reported on “unmarried gentlemen” who smoked opium with their white dates before laying down together to “sleep off its effects.”[26] Hinting at the possible outcomes of these taboo activities, the Evening World mockingly quipped that “a number of the merchants had their white wives and cute half-breed children with them.”[27] The next week, the Philadelphia Inquirer called the engagement of grocer Huet Sing to Florence McGusty a “sequel to the great heathen picnic.”[28] Most Chinese American men who dreamed of marriage and family partnered with white women, as biased enforcement of the 1875 Page Act—which banned immigrants who might pursue “lewd and immoral purposes”—targeted Asian women. These interracial unions triggered a stereotype that cast men of Chinese descent as sexual predators. This racist myth was what eventually brought about the end of Sunday school excursions. The News described “pretty Sunday school teachers” watching students who played “in their childlike way” on an excursion in 1886, but assumptions that these Chinese American men were naïve and asexual eroded the next decade.[29] In 1895, the Police Illustrated News reported that a white teacher went “in the shrubbery” at Iona Island with her “favorite Sunday School scholar.” Making it clear what the pair were up to, the paper noted that many “slant-eyed children of white women by Chinese fathers” attended the trip too.[30] Then in 1909, the body of Sunday school teacher Elsie Siegel was found in a trunk in Chinatown. As authorities searched for her murderer, the media cast suspicion far beyond her classroom and acquaintances—towards all Chinese Americans.[31] The annual excursion was canceled, as newspapers from as far away as Minnesota reported that “there were many Lotharios among these Chinamen, sleek satiny yellow men, who boasted of their conquests of young pretty teachers.”[32] The annual excursion became a threat, rather than a boon, to the reputations of Chinese Americans. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, New Yorkers of Chinese descent used steamboat excursions to make a case for their belonging. Sunday school students showcased friendly relationships with their teachers along with their religious and cultural assimilation. Members of the Knee Hop Hong proudly practiced traditions from China as they sailed out of New York Harbor, asserting that they could be Chinese and American at the same time. Both encountered suspicion and harmful stereotypes that only grew in the following decades, as the Chinese Exclusion Act was extended multiple times and expanded to cover most of Asia. Excursions aimed to soften views of immigration from China, but there was no escaping xenophobia and racism during the long era of Chinese exclusion—even during a holiday away from daily urban life. Endnotes: [1] “A Celestial Racket,” Truth, June 12, 1883, 1. [2] Iona Island Application to General Services Administration, May 20, 1965, Bear Mountain Archives at Iona Island, Palisades Interstate Park Commission. [3] “The First Chinese Picnic,” New York Times, June 12, 1883, 1. [4] “The First Chinese Picnic,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 17, 1883, 1. [5] “The Coming Coolie,” New York Times, July 1, 1870, 1. This protest responded to the hiring of 68 Chinese immigrants to work at the Passaic Steam Laundry in Belleville (now Newark), NJ. More people of Chinese descent were settling in East Coast cities, as violence on the West Coast pushed them away. Tyler Anbinder, City of Dreams: The 400-Year Epic History of Immigrant New York (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016), 521. [6] Erika Lee, America for Americans: A History of Xenophobia in the United States (New York: Basic Books, 2019), 73-112. [7] “Mails from China and Australia,” New York Times, May 20, 1883, 10; “The Baptist Pastors,” New York Times, March 14, 1882, 3. [8] “The Chinese Excursion,” Evening Telegram, June 9, 1883, 1. [9] “The First Chinese Picnic,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 17, 1883, 1. [10] “The First Chinese Picnic,” New York Times, June 12, 1883, 1. For views of Chinese immigrants as incapable of assimilation, see Tyler Anbinder, Five Points: The 19th-Century Neighborhood That Invented Tapdance, Stole Elections, and Became the World’s Most Notorious Slum (New York: The Free Press, 2001), 422; John Kuo Wei Tchen, New York before Chinatown: Orientalism and the Shaping of American Culture 1776-1882 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999), 266-278. [11] “Chinamen have a Picnic,” New-York Daily Tribune, June 9, 1885, 5; “Chinamen in New York,” The News, July 23, 1886, 1. [12] “A Celestial Racket,” Truth, June 12, 1883, 1. [13] Joss houses are statues that believers in Taoism, Confucianism, Buddhism, and ancestor worship care for as homes to deities. Older stock New Yorkers were highly suspicious of Chinese religion. Anbinder, Five Points, 417-418. [14] “The First Chinese Picnic,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 17, 1883, 1. [15] “Chinamen on a Picnic,” New-York Daily Tribune, July 24, 1888, 5; Anbinder, Five Points, 407, 410, 413. [16] Wong Chin Foo, “A Heathen Picnic,” The Sun, July 16, 1888, 5. [17] By the time the neighborhood gained the name “Chinatown” in the 1880s, few Chinese American New Yorkers lived there, instead settling throughout the city and Brooklyn near the laundries where most they worked. But they went to Chinatown to shop and socialize. Daniel Czitrom, New York Exposed: The Gilded Age Police Scandal that Launched the Progressive Era (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), 396-401; Anbinder, Five Points, 405. [18] While many New Yorkers of Chinese descent were among the city’s lowest paid workers, some had amassed fortunes. Anbinder, Five Points, 403. [19] “Chinatown’s Mayor Dead,” New York Times, January 11, 1918, 6; Arthur Bonner, Alas! What Brought Thee Hither? The Chinese in New York, 1800-1950 (Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1997), 85; Anbinder, Five Points, 410-413. [20] “The Chinamen’s Picnic,” New York Times, July 23, 1888, 8. [21] Wong Chin Foo, “A Heathen Picnic,” The Sun, July 16, 1888, 5. [22] Wong Chin Foo, “A Heathen Picnic,” The Sun, July 16, 1888, 5. [23] “Chinamen on a Picnic,” New-York Daily Tribune, July 24, 1888, 5. [24] “Knee-Hop-Hongs on a Lark,” Evening World, July 23, 1888, 2. [25] “The Heathen Chinese,” The Sun, July 24, 1888, 2. [26] “The Heathen Chinese,” The Sun, July 24, 1888, 2. [27] “Knee-Hop-Hongs on a Lark,” Evening World, July 23, 1888, 2. [28] “A Heathen Captures a Christian Heart,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, July 26, 1888, 1. [29] “Chinamen in New York,” The News, July 23, 1886, 1. [30] “Ching a Ling’s Picnic,” Illustrated Police News, June 22, 1895, 3. [31] Mary Ting Yi Lui, The Chinatown Trunk Mystery: Murder, Miscegenation, and other Dangerous Encounters in Turn-of-the-Century New York City (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005); Bonner, Alas!, 120. [32] “Boasts of the Pagans,” The Duluth Evening Herald, June 25, 1909, 6. AuthorDr. Marika Plater studies steamboat excursions as a window into environmental inequity in nineteenth-century New York City. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

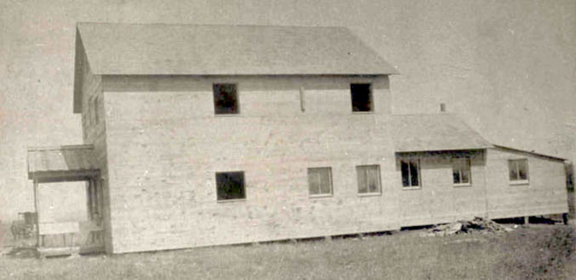

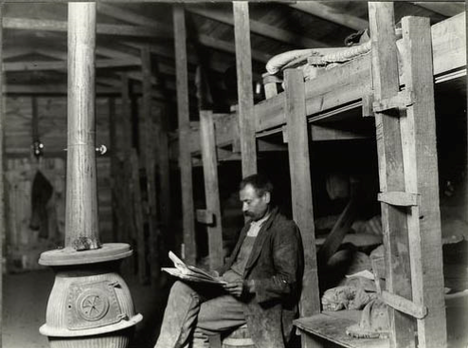

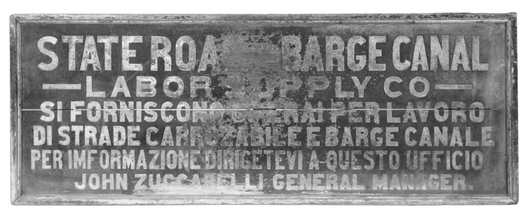

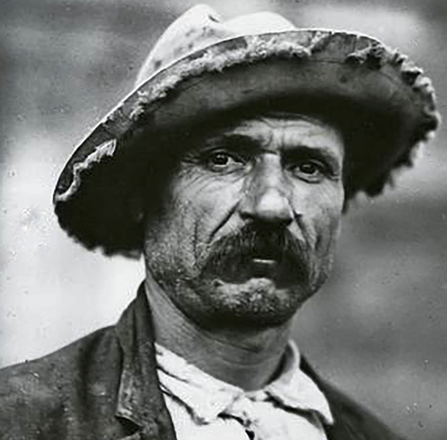

EDITOR’S NOTE: In 2018, the Hudson River Maritime Museum opened the Hudson River and its Canals exhibit to help celebrate the 200th anniversary of the construction of the Erie and Champlain canals between 1817 and 1825. These canal led to far reaching economic and social changes for the areas adjacent to these canals but also for New York City and the Hudson River upon which this system ultimately depended. The Barge Canal system, the backdrop for Paul Schneider’s article, was, completed little more than 100 years ago. Built upon the work of the earlier canals, it was conceived instead on the use of motive power versus animal power. And yet much of the construction still depended upon human labor. Paul Schneider’s article provides important insight into the labor practices and culture surrounding this enormous public works undertaking. On a dreary November day three women and a photographer trudged through rain to examine conditions in a construction labor camp on the state’s barge canal. In one of the unkempt shacks housing workers, they “came upon an Italian who seemed to feel the camp[’s] desolation. He sighed as he said to us: ‘This, America?’” After proudly sharing photographs, pulled from his bunk, of Rome and of his children, “he pointed again to the waste of mud and water [outside]. ‘This, America?’ he said, ‘All for nine dollars a week.’”1 This encounter occurred in 1909. The building of the barge canal system had been underway for four years. An additional nine years would pass before the massive undertaking spanning the state was completed. Now in its 101st year of operation, the New York State Barge Canal System is most easily recognizable by the enormous concrete structures that define it: hulking locks punctuated by gigantic steel gates, immense dams spanning and transforming the Mohawk River, and distinctive powerhouses once generating the electricity to operate each lock and the valves that filled and emptied it. Designated a National Historic Landmark in 2017 as “an embodiment of the Progressive Era emphasis on public works,” the barge canal was further recognized as “a nationally significant work of early twentieth century engineering and construction.”2 In 2015, the American Society of Civil Engineers named the five locks at Waterford, New York as a Historical Civil Engineering Landmark representing “the greatest series of high lift locks in the world … elevating boats through a height of 169 feet."3  As this photograph of a boarding house for workers employed on the Champlain section of the barge canal illustrates, housing conditions varied according to the contractor responsible for a specific phase of work. Although appearing neatly built and a great improvement of over the shacks visited by the investigating committee, it is quite possible that this house was intended for skilled workers rather than unskilled immigrant laborers. Handwritten annotations on the bottom of this image state that the house was taken down after the project was completed. Courtesy of the Mechanicville District Public Library. Largely overlooked in the superlatives emphasizing engineering and construction prowess are the thousands of un-skilled laborers – many of them immigrants – whose back-breaking and often dangerous work made its construction possible. There are no monuments to them. No preserved shacks or reconstructed labor camps to reveal to modern visitors the conditions in which these laborers lived and worked. The four unannounced callers to that unspecified construction camp were making an automobile tour – an arduous undertaking itself in that early era of auto travel – visiting similar camps associated with major governmental construction projects. In addition to the state barge canal system, New York City’s Board of Water Supply was, by damming the Esopus Creek in Ulster County, constructing the immense Ashokan Reservoir, linking it by a 120-mile long aqueduct to deliver an increased supply of water to the city.4 The small group of intrepid travelers included two members of the New York State’s Commission of Immigration, Lillian D. Wald and Frances A. Kellor. They were accompanied by Mary Dreier and photographer Lewis W. Hine. A founder of the Henry Street Settlement House (which celebrated its 125th anniversary in 2018) in New York City, Lillian Wald was forty-two years old. While focusing her dynamic energies in the Lower East Side, she had expanded her advocation for improving the health, education, working and living conditions of the poor and immigrant communities to a state and national level. She invited the then serving Republican governor, Charles Evans Hughes, to Henry Street in 1908 and persuasively made her case regarding the exploitation of immigrants. In response, Governor Hughes appointed both she and Frances A. Kellor to the nine-member commission mandated by the state legislature to "make full inquiry, examination and investigation into the condition, welfare and industrial opportunities of aliens in the State of New York."5 Frances A. Kellor, described as a “hard-driving personality,” was thirty-six, had earned a law degree from Cornell University Law School in 1897, studied the newly emerging fields of sociology and social work at the University of Chicago, where she lived in Jane Addams Hull-House, and then in 1903 moved to New York City and the Henry Street Settlement House, where she concentrated her attention on the “difficulties of immigrants and other minorities in gaining equal treatment and opportunity in U.S. society.”6 Mary Dreier, age thirty-four, was at the time, the president of the New York Women’s Trade Union League. Characterized as “an ally of workers,” she, like Kellor, “believed that reform was best achieved by investigation, analysis, and legislation."7 The fourth member of the group, the photographer Lewis Wickes Hine, was the youngest at thirty-two. Writing of Hine’s work, American photographer, Walter Rosenblum suggests that, “the social turmoil of the Progressive period of American history was the fabric of his vision.” The work camp conditions he saw through his 5 x 7 view camera became part of that vision.8 What the lone Italian laborer sitting in the dismal surroundings of his work camp must have thought when these four suddenly trooped in unannounced is not recorded. Certainly, he must have been surprised by the fact that three of them were women. Wald, in her 1915 book, The House on Henry Street, records the meeting with a bit more detail: In a shack that held three tiers of bunks, occupied alternately by the day and night shifts, with a cook-stove in a little clearing in the middle, we found a homesick man, who chanced not to be on the works, reading a book. When we engaged in conversation with him he pointed contemptuously to the bunks and their dirty coverings, and said, "This America! I show you Rome," and produced from under his bed a photograph of the Coliseum.9  The homesick Italian laborer who Wald, Kellor, Dreier and Hine encountered in a state barge canal work camp in November 1909. Black and white photograph by Lewis Wickes Hine. Courtesy of the New York Public Library, Digital Collections, the Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection. The photograph shown above is of that same “homesick” laborer quoted above. This photograph was one of twenty taken by Hine that graphically illustrated Wald and Kellor’s report on the findings of their investigation published in the January 1910 issue of The Survey. Wald’s criticisms of what she, Kellor, Dreier, and Hine discovered are blunt: [The state] takes great care to prevent the freezing of cement, but permits any kind of houses to be used for its laborers. It is wholly indifferent as to how they are ventilated, lighted, or heated, how many men sleep in them, or whether the sleeping quarters are also used for cooking and eating and the bunks as cupboards. Neither does it care whether the men can keep themselves or their clothes clean.10 Quoting a New York Times article, The Albany Evening Journal of Tuesday, January 4, 1910 noted that the investigators discovered that “the mules were found to be housed in better quarters than the laborers.” Further, the reprinted article stated that, “One entire state camp consists of five buildings. The largest about 50 by 20 feet, contains 52 bunks in a double tier and has a small stove for heating and cooking. The windows are closed tightly and there is one door. This building is set flat upon the side of the canal, upon swampy ground in the midst of mud so deep that on the day of the visit it was necessary to wear rubber boots.”11 Wald and Kellor in their published report articulated their belief that “here in a democracy, in our greatest creative achievements, we can set standards which will make for democracy and not for petty despotism, immorality and physical deterioration. State and city can set standards for life and labor in the construction camps, and see that they are enforced, as easily as they can determine the grade of stone used and the tensile strength of steel.”12 Particularly in the state barge canal camps, however, what they found fell far short of such standards. “With one exception, they found state and city personified, so far as the immigrant workers were concerned, by the padrone whose largest profits are to be drawn from the vice, drunkenness, instability and ignorance of the men …. In state camps they found the padrone in full control, supplying job, bed, board and drink; they found a building with sixty-five cots for a hundred men, another with bunks in the dark cellar; they found state camps wholly dependent upon any spring, well or pump in the neighborhood; they found nuisances committed without restriction, the grounds filthy, and no means for recreation.”13 Who was the “padrone” Wald and Kellor referred to so vehemently? The word had its origins in fourteenth century Italy according to the Oxford English Dictionary. At that time, it referred to the master of a ship. The term came to be associated in the United States with “an exploitative (usually Italian) labor contractor, who employs unskilled Italian immigrants.”14 On the state and city government construction projects that Wald, Kellor, Dreier and Hine were investigating during their auto tour, the padrone acted as the intermediary between the construction contractor and the unskilled laborers that contractor required. This freed the governmental agencies responsible for these massive projects from having to recruit, care for, administer, manage, and supervise the huge temporary workforce needed to turn plans and specifications into physical and monumental reality.  Detail of a Lewis Wickes Hine photograph published with their 1910 investigative report. Its caption read in part: “A Camp Bar. Connecting through a store with the sleeping quarters… The other furnishings consist of tables for card playing and gambling. The ‘commissaire’ (the padrone owner) of this establishment was asked if he needed policemen to keep order. ‘Me the sheriff,’ he said. Courtesy of the New York Public Library, Digital Collection, the Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection. In 1909 the padrone system was already decades old: a proven method of acquiring cheap labor needed to construct dams, railroads, canals, and roads in addition to mining operations of all types throughout the United States.15 It was extremely exploitive of those unskilled workers on whom it depended. John Koren in an 1897 report he wrote for the federal Department of Labor described in detail how it worked. The American contractor, wishing to secure the cheapest possible labor wherewith to carry out some new enterprise, would apply to a resident Italian immigration agent (soon to be dignified by the name ‘banker’) for a stated number of men. The latter, having through subagents in Italy collected as many as required, shipped them across on prepaid tickets, for which he received a stipulated commission. On arrival of these immigrants the agent would make an additional profit by boarding them at exorbitant prices until they could be sent to their destination, the expense being deducted from their prospective wages. The further privilege of supplying them with food and shelter while at work was also commonly granted the agent, and if a banker, he could from time to time add to his profits by charging unreasonable rates for sending the scanty savings of the laborer to Italy. Finally, he had in prospect a commission on the return passage to Italy when the contract expired, for the immigration then as now, was chiefly of a migratory character. Few remained here beyond the time of their contract….16 The lonely Italian laborer encountered by Wald, Kellor, Dreier, and Hine had undoubtedly undergone something very similar to find himself sitting in that work camp shack in November 1909. While Hungarians and immigrants from Slavic countries were also caught up in the clutches of the padrone system, the majority of unskilled laborers came from Italy, specifically from southern Italy. In a report published in 1907 for the federal Bureau of Labor, Frank J. Sheridan included numerous tables of statistical information clearly showing the higher percentage of unskilled laborers immigrating into the United States and especially into New York State were southern Italians. For example, in the span of a year ending in June of 1906, 117,119 immigrants from southern Italy versus just 12,984 from northern Italy came to New York.17 The historic causes that created this late-nineteenth through early-twentieth century geographic wave are far too complex to address in this article. However, Sheridan presents three primary reasons driving “common laborers” to leave their native countries: “(1) primary necessity; (2) to escape compulsory military service and other burdens; (3) to become self-supporting.”18 Another compelling reason was unremitting poverty. Historian Michael La Sorte writes, “by the decade of 1910 Italians in the United States were sending home large sums of money …. for some families back home, this money represented a large portion of their total income.”19 Wald and Kellor echo this in the opening sentence of their 1910 report on the work camps: “Word has gone down the line and across the water that New York state is ‘America’ and that a ‘harvest is on.’ Thousands of alien laborers, writing home or returning to Italy or Austria, have told their countrymen of ‘America’ as they have seen it …”20  Large exterior sign advertising for laborers to work on both state roads and the barge canal. The Auburn Citizen newspaper for Monday, April 25, 1910 ran a notice under the headline, “Work for Italians,” that “John Zuccarelli, the general manager of the Barge Canal Italian Laborers’ Supply Company with headquarters at No. 26 Jefferson Street, has secured the contract from Morris Kantrowits of Albany, N.Y. to furnish 160 men of whom 50 will be set to work at once.” The sign is in the collections of the New York State Museum. Image is provided courtesy of the New York State Museum, Albany, NY. The expectations raised by such words going “down the line,” were often dampened by the reality immigrants found. For not only were the living conditions many were forced to endure terrible, but often their very presence was resented. The construction of the barge canal itself had faced considerable opposition from those who saw it has an enormous expenditure by the state in an outmoded form of transportation. A printed circular advancing opposition arguments was published in May 1903, asserting in part that, “if the policy of the State requires the expenditure of the State’s moneys for the purpose of creating facilities for transporting freight in competition with the existing railroads, why should it not be better for the State to construct a four track railroad from Buffalo to Albany along the present route of the Erie canal?”21 The same circular also pressed home an anti-immigrant labor contention: “if carried through, the enterprise is sure to injure the laboring population now employed to the upmost and to bring … tens of thousands of foreign laborers of the lowest type, who will remain when the work is done a drag on our own civilization and a menace to our native workers.”22 Obviously, the opposition challenges to the barge canal’s construction failed, but criticism remained as the actual work proceeded slowly. The Buffalo Times newspaper for Sunday, August 22, 1909, for example, reported on the findings of a tour of inspection a group of state legislators had just completed. Senator Henry W. Hill of Buffalo was quoted as saying, “we found the work progressing very satisfactorily in most places and the contractors generally entering into the work with enthusiasm.” He also asserted that the “undertaking …. in some respects is more difficult than the building of the Panama Canal, because the New York waterways involve so many more engineering and hydraulic problems.”23 Within such an atmosphere, it seems fair to conclude that both state officials in charge of the work and the contractors hired to implement it were under pressure to pursue construction with as much speed and economy as possible. Tellingly, the 1910 inspection tour by the legislators did not mention the laborers toiling across the state or the conditions under which they lived and worked. Did Lillian Wald or Frances Kellor or Mary Dreier or Lewis Hine – each of whom were well versed in the plight of immigrants coming into New York – tell the lonely Italian laborer they met in that barge canal work camp, that his experience was far from unique? We will never know, unless some written record of their visit eventually is found. His fellow countryman, Napoleone Colajanni, writing in 1909 bitterly observed that “the Americans consider the Italians as unclean, small foreigners who play the accordion, operate fruit stands, sweep the streets, work in the mines or tunnels, on the railroad or as ‘bricklayers.’”24 In fact, far more Italian immigrant laborers were employed on railroad construction in the northern states than on both the city and state construction projects Wald and her party were visiting. The living and working conditions of these workers were similar if not worse in some cases.25 It is from the experiences of those Italians in railroad construction work camps reported by Frank Sheridan that we finally hear the actual voices of some of these men. Sheridan writes that their declarations were given in evidence of the abuses they had undergone while working on railroad construction projects. He also notes that their words “are translations from the statements made in Italian by each of the laborers.”26 Below is just a portion extracted from one such statement. Names and locations were deleted in the original. "During the summer of 1903 I was working on the _________ Railroad in the gang of ______, and was lodged at the shanties conducted by [the padrone] at _________. On account of the unhealthy conditions of the shanties, the rottenness of the groceries sold in the store therein, and the exorbitant prices charged, I couldn’t live there and I quitted work. I had to sleep on a handful of straw [charged 25 cents], pay $1 monthly for rent of the shanty, 25 cents per month for lamp and light, 50 cents monthly for coal, beer 6 cents per bottle, 1 ½-pound loaf of bread 10 cents, macaroni 8 cents per pound, tomatoes 14 cents a can, cheese 36 and 40 cents per pound …. and not only that, but bound to spend at least $10 per month, and with such high prices $10 was not enough to keep a man in shape for work fifteen days. Further, to secure work on the _______Railroad at such conditions, I had to pay to [the padrone] $10 [$5 per time] otherwise he wouldn’t allow me to work.27" Today, we might think such prices remarkably cheap until we are reminded that unskilled Italian laborers were typically charged amounts that “were never less than two to four times the prevailing market prices.”28 So, for example, if a consumer paid $2.35 for a loaf of fresh white bread today in 2019, the immigrant buying that same loaf from the padrone run store in a work camp might be charged anywhere from $4.70 to $9.40. It is small wonder that workers sometimes simply walked away looking for better work and living conditions, sometimes scrimped together enough money to return to Italy, sometimes tenuously managed to establish themselves in the communities near where they worked, and sometimes simply had enough and attacked the padrone or his representatives. Late in April of 1908 this is exactly what happened in Waterford, New York. The Wyoming County Herald ran a story datelined April 29, Troy, which reported that: “a riot occurred among the Italians employed on the barge canal work at Waterford. The padrone who places men at work, it is charged, gets $5 from each man and then if the man does not trade at the supply store conducted by the padrone, that person is discharged, and another is hired. Several hundred Italians descended upon the store and there was a free fight in which clubs and fists were freely used. The Italians prevented all work at the section. Deputy sheriffs were necessary to quell the riot.29" What happened to either the padrone or the rioting laborers is not reported, but it illustrates the sheer frustration and anger that could build-up in the confines of the laborer camps. While not all canal construction workers lived in such camps, they represent what was an indispensable component in the creation of the barge canal system; a massively re-imagined and re-engineered waterway that served the state’s and nation’s urgent needs for the shipment of materials, fuel, and equipment during both World Wars I and II.  Detail of Lewis Wickes Hine famous portrait of an Italian laborer on the NYS Barge Canal. Hine has captured the rough-hewn character, weariness, and dignity of this individual. Courtesy of the New York Public Library, Digital Collection, the Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection. Today’s barge canal is characterized by pleasure boats, kayaks, tour boats, and leisurely piloted rental canal boats carrying visitors eager to experience its beauty and to explore the villages, towns, and cities it connects. Walkers, joggers, and bicyclists ply its banks along paved towpaths, the original need for which was eliminated by the self-powered vessels and towing tugs that replaced horses and mules from the pre-barge canal era. In the reigning tranquility of the canal today, its users hear no echoes of the shouts, groans, cries of pain or anger, laughter, insults, name calling, curt orders, hammers, squeaking wheel barrow wheels, dynamite detonations, shrill whistles and exhaust blasts from steam dredges and locomotives, and the myriad of other sounds that heralded its birth. The physical remains of those flimsy structures composing the work camps where thousands temporarily lived amid those sounds are long gone, but the human lives they barely sheltered are woven into the fabric of the history of the state. 1 Lillan D. Wald and Frances A. Kellor, “The Construction Camps of the People: The Findings of an Automobile Tour of Investigation of Camp Conditions Along the Line of New York State’s New Barge Canal and New York City’s New Aqueduct,” The Survey, January 1, 1910, 460 (hereafter cited as Wald, “Construction Camps”). The Survey was published by the Charity Organization Society of New York City, founded in 1882 and characterized as “one of the most influential philanthropic organizations in New York City.” For this quote see Anne M. Filiaci, “Lowell and the Charity Organization Society of New York,” accessed 30 December 2018, http://www.lillianwald.com/?page_id=216. 2 National Historic Landmark, A National Honor” Erie Canal National Heritage Corridor website, accessed 27 December 2018, https://eriecanalway.org/resources/NHL. 3 “Flight of Five Locks,” ASCE American Society of Civil Engineers, Historic Landmarks, accessed 27 December 2018, https://www.asce.org/project/flight-of-five-locks/. 4 Edward Hagaman Hall, The Catskill Aqueduct and Earlier Water Supplies of the City of New York […] (New York: The Mayor’s Catskill Aqueduct Celebration Committee, 1917), 112. “The length of the aqueduct from Ashokan to this reservoir [Silver Lake Reservoir in Staten Island] is 119 miles, to be exact, but it is called 120 miles in round numbers.” 5 Report of the Commission of Immigration of the State of New York (Albany, NY: J. B. Lyon Company, 1909), 1. For an overview of the history of the Henry Street Settlement House and Lillian D. Wald visit its website at: https://www.henrystreet.org/about/our-history/exhibit-the-house-on-henry-street/ and especially view the short video there “Baptism of Fire – The House on Henry Street.” 6 Allison D. Murdach, “France Kellor and the Americanization Movement,” Social Work 53, no.1 (January 2008): 93. 7 Ann Schofield, "To do & to be": portraits of four women activists, 1893-1986 (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1997), 50, 60. 8 Walter Rosenblum, foreword to America & Lewis Hine: Photographs 1904-1940 (New York: Aperture, 1997), 12, 15. 9 Lillian D. Wald, The House on Henry Street, with a new introduction by Eleanor L. Brilliant, (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 1991). First published 1915 by Henry Holt and Company. 295, (hereafter cited as Wald, House on Henry Street). 10 Wald, House on Henry Street, 296. 11 “Barge Canal Labor,” The Albany Evening Journal (Albany, NY), January 4, 1910. 12 Wald, “Construction Camps,” from the Foreword, unpaginated, following page 448 13 Wald, “Construction Camps,” from the Foreword, unpaginated, following page 448 14 “padrone,” Oxford English Dictionary online, accessed February 9, 2019, http://www.oed.com.dbgateway.nysed.gov/view/Entry/135946?redirectedFrom=padrone#eid. The plural of padrone is padroni. 15 Edwin Fenton asserts that the padrone system dates to the 1840s, while John Koren, writing about it for the Department of Labor in 1897, says its origins “are not easily traced” but seems to have come into prominent use after the Civil War during industrial recovery and growth during “which capital sought labor with almost reckless eagerness.” See Edwin Fenton, Immigrants and Unions, A Case Study: Italians and American Labor, 1870-1920 (New York: Arno Press, 1975), 77, and John Koren, "The Padrone System and Padrone Banks," Bulletin of the Department of Labor 9, March 1897 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1897), 113, hereafter cited as Koren, “The Padrone System.” 16 Koren, “The Padrone System,” 114. 17 Frank J. Sheridan, “Italian, Slavic, and Hungarian Unskilled Immigrant Laborers in the United States,” Bulletin of the Bureau of Labor 72, September 1907 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1907), 409. 18 Sheridan, “Immigrant Laborers,” 406. 19 Michael La Sorte, La Merica: Images of Italian Greenhorn Experience (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1985). 5. 20 Wald, “Construction Camps,” 449. 21 This circular is quoted in Henry Wayland Hill, “An Historical Review of Waterways and Canal Construction in New York State,” Buffalo Historical Society Publications, 12 (Buffalo: Buffalo Historical Society, 1908), 346. 22 Hill, “Historical Review,” 347. 23 “Four Years Yet on Barge Canal, Says H. W. Hill,” The Buffalo Times (Buffalo, NY), August 22, 1909. The Senator Hill quoted in the news article is very likely the same Henry W. Hill who wrote the 1908 article quoted in footnote 21. 24 This quotation is from Napoleone Colajanni, Gli Italiani negli Stati Uniti (Napoli: Rivista Popolare, 1909), 44, translated and cited in La Sorte, La Merica, 61. 25 In a table included with Frank Sheridan’s 1907 report illustrated the numbers and percentages of various immigrant nationalities (dominated by Italians, Slavs, and Hungarians) employed in various occupations in both northern and southern states. In the North fully 75.93 percent of those immigrants engaged in railroad construction and repairs were Italians. Those immigrants in occupations categorized as “canal construction laborers” or “dam and waterworks construction,” were quite small by comparison. Sheridan’s breakdown of occupations may distort his results. For example, “excavating laborers, ditching laborers, and concrete and cement laborers” could all have been employed on either the barge canal or the Ashokan Reservoir projects. Also, his numbers are based on immigrants sent to these occupations by New York Employment Agencies and very likely do not reflect those hired out through the difficult to regulate padrone system. See Sheridan, “Immigrant Laborers,” 420. 26 Sheridan, “Immigrant Laborers,” 445. 27 Sheridan, “Immigrant Laborers,” 447. 28 La Sorte, La Merica, 81. 29 “Riot Among Barge Canal Laborers,” Wyoming County Herald (Arcade, NY), May 01, 1908. AuthorPaul G. Schneider, Jr. is an independent historian and a member of the National Coalition of Independent Scholars. This article was originally published in the 2019 issue of the Pilot Log. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

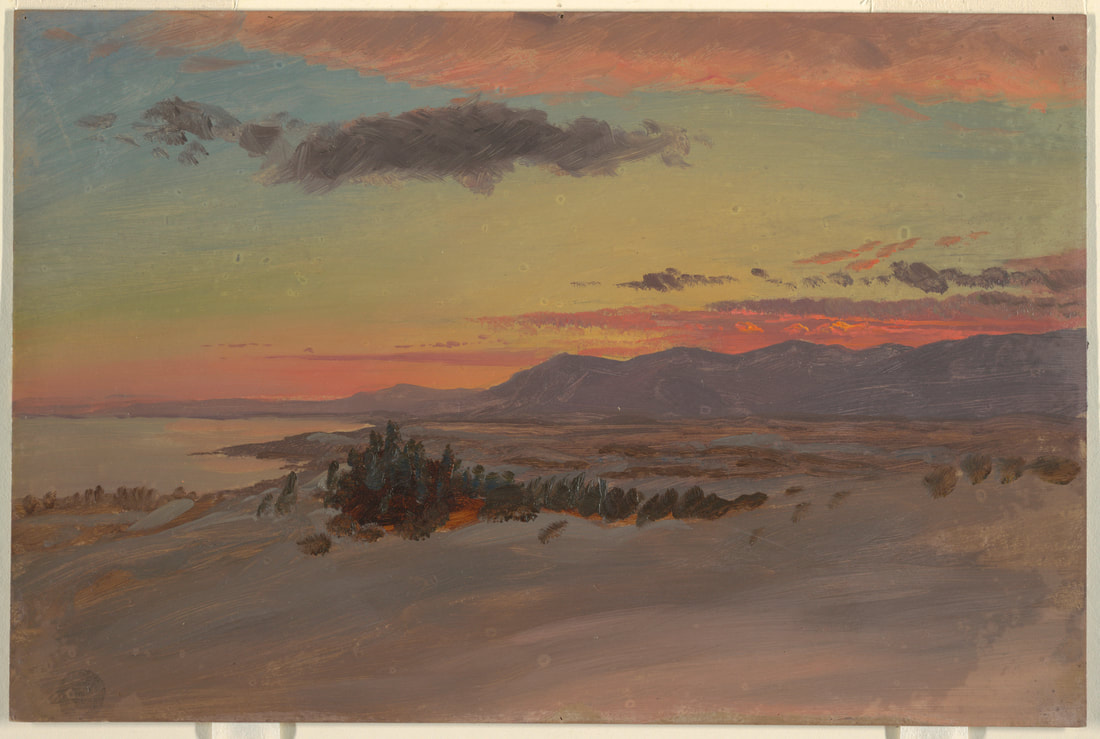

The book American Husbandry. Containing an ACCOUNT of the SOIL, CLIMATE, PRODUCTION, and AGRICULTURE, of the BRITISH COLONIES in NORTH AMERICA and the WEST-INDIES; with Observations on the Advantages and Disadvantages of settling in them, compared with GREAT BRITAIN and IRELAND was published in Britain in 1775, and written, anonymously, "by an American." It is a fascinating little piece - an attempt to convince Britons of the superiority of American soil, beauty, and even the Hudson River, to that of England. Of particular interest to us in the Hudson Valley, of course, is the chapter specifically on New York. The chapter begins with a discussion of climate and the various types of soils suitable (or not) for agriculture, often comparing New York to New England, which perhaps was more familiar to Britons at the time. But of course, the thing that caught our eye the most, was the description of the Hudson River: "The river Hudson which is navigable to Albany, and of such a breadth and depth as to carry large sloops, which its branches on both sides, intersect the whole country, and render it both pleasant and convenient. The banks of this great river have a prodigious variety; in some places there are gently swelling hills, covered with plantations and farms; in others towering mountains spread over with thick forests: here you have nothing but abrupt rocks of vast magnitude, which seem shivered in two to let the river pass the immense clefts; there you see cultivated vales, bounded by hanging forests, and the distant view completed by the Blue Mountains raising their heads above the clouds. In the midst of this variety of scenery, of such grand and expressing character the river Hudson flows, equal in many places to the Thames at London, and in some much broader. The shores of the American rivers are too often a line of swamps and marshes; that of Hudson is not without them, but in general it passes through a fine, high, dry and bold country, which is equally beautiful and wholesome."  Drawing, Hudson Valley in Winter, Looking Southwest from Olana, Frederic Church, 1870-1880. A snow covered plain is shown in the foreground and right middle distance. The Catskill mountains stretch from the right toward the left distance. Part of the Hudson River is shown in the left middle distance. The sky has light clouds with orange above the mountains and along upper edge. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. "They sow their wheat in autumn, with better success than in spring: this custom they pursue even about Albany, in the northern parts of the province, where the winters are very severe. The ice there in the river Hudson is commonly three or four feet thick. When professor Kalm [Peter or Pehr Kalm, who visited in 1747] was here, the inhabitants of Albany crossed it the third of April with six pair of horses. The ice commonly dissolves at that place about the end of March, or the beginning of April. On the 16th of November the yachts are put up, and about the beginning or middle of April they are in motion again." The chapter ends with a discussion of New York's agriculture, which grains were commonly planted where, the role of beer and hard "cyder" in everyday life, and all the possible agricultural goods and raw materials that could be exported. Of American Husbandry, the British Royal Collection Trust writes, "Written anonymously by 'An American', this is a remarkable work on the climate, soil and agriculture of the British colonies in North America immediately prior to the outbreak of the American War of Independence. It covers all the major British possessions, starting in Canada, before moving through the thirteen colonies, the Caribbean and the newly-acquired territories in Ohio and Florida. It looks, not only at the environment of these colonies, but also at which plants have been successfully cultivated, demographics, the value of different commodities to Britain and recommendations on how to improve farming methods. "Beyond the bulk of the text there are numerous references to the unsettled state of affairs in the region and the threat of an American declaration of independence, and the author dedicates the final two chapters of the second volume to the subject. Interestingly, he implies that independence is inevitable, being just a matter of time until the colonies would outgrow the mother-country, be it through population, commerce or grievance, but suggests several methods to postpone it such as: the acquisition of the French-held Louisiana territory beyond the Mississippi river or the establishment of a political union between Britain and America with the representation of American politicians in Parliament." The fact that this book was published on the eve of the American Revolution is remarkable. The First Continental Congress had already sent its first "Petition to the King" to call for the repeal of the "Intolerable Acts" (also known as the "Coercive Acts") in 1774. The Intolerable Acts were a series of punitive reactions to the Boston Tea Party, closing Massachusetts' ports, revoking its charter, extraditing colonial government officials accused of a crime back to Britain (where they faced friendlier juries), and quartering British soldiers in civilian homes. The petition was ignored and the Intolerable Acts were not repealed. In July of 1775, the Second Continental Congress penned and approved what is now known as the "Olive Branch Petition," which was delivered to London in September, 1775. A controversial last ditch effort to avoid war with Great Britain, this petition also failed, leading to the Declaration of Independence in 1776. Against the backdrop of this political, social, and economic turmoil, American Husbandry becomes that much more interesting. A largely glowing report of the settlement prospects of the American colonies, it attempted to persuade immigration and investment, even as the two nations it sought to unite - the British Empire and the soon-to-be-new nation, the United States - were on the brink of war. One wonders - were any Britons influenced by this book, choosing to emigrate during this turbulent time? If so, which side of the conflict did they adopt in their new home? We may never know. If you'd like to read the whole book, or the chapter on New York for yourself, you can find the full text of American Husbandry here. AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson is the Director of Exhibits & Outreach at the Hudson River Maritime Museum, where she has worked since 2012. She has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

|

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 [email protected] Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |