History Blog

|

|

|

|

|

“The maintenance of a merchant marine is of the utmost importance for national defense and the service of our commerce.” President Calvin Coolidge “In peacetime, the U.S. Merchant Marine includes all of the privately owned and operated vessels flying the American flag – passenger ships, freighters, tankers, tugs, and a wide miscellany of other craft. Merchant Marine vessels ply the high seas, the Great Lakes, and the inland waters, such as the Chesapeake Bay and navigable rivers.” Heroes in Dungarees by John Bunker During the colonial period, businessmen and legislators realized that prosperity was connected to trade. The more shipment of imports and exports through colonial ports the more money there was to be made. Carrying American produced goods to market in American made and managed ships kept the money in American pockets. Formation of the United States Merchant Marine is dated to 1775 when citizens at Machias, Massachusetts (now Maine) seized the British schooner HMS Margaretta in response to receiving word of the Battles of Lexington and Concord. After the Revolutionary War American ships were no longer under the protection of the British empire. The new nation offered incentives for goods to be moved on American ships. Wars on the European continent turned attention away from American activity as U.S. ships opened up new trade routes in the early Federal period. The Empress of China reached China in 1784, the first U.S. registered ship to do so. American shipping and shipbuilding flourished in the early 1800s. The years between the War of 1812 and the Civil War saw the development of canal systems connect the western interior with seaport markets. “Those years saw the merchant marine rise to its zenith in terms of the percentage of American trade carried. Only in the aftermaths of World Wars I and II would its percentage of world tonnage stand as high.” America's Maritime Legacy by Robert A. Kilmarx Sail powered packet ships, carrying passengers, pushed their crews hard. There was money to be made in quick passages across to Europe and back. Clipper ships also relied on speed as they carried high value cargoes of silk, spices and tea across the Pacific and the slave trade across the Atlantic. The hybrid sailing ship/sidewheeler steamer Savannah’s 1819 Atlantic crossing, the first with a steam powered engine, signaled the start of the transition from sail to steam. The May 22 date for National Maritime Day commemorates the day Savannah set sail from Savannah, Georgia to England. The Savannah transported both passengers and cargo. More information about the SS Savannah is here: Restoration of the merchant marine after the disruption of the Civil War was a national political issue in 1872. The Republican party advocated adopting measures to restore American commerce and shipbuilding. Mail packets, carrying mail around the world were active in this period. Financial scandals were associated with mail packet contracts. Training sailors in an academic setting began in the last quarter of the 1800s, predecessors of the present day Maritime Academies. The period between the end of the Civil War in 1865 and the European outbreak of World War I was a dynamic time for shipping. American raw materials and agricultural products were shipped to world markets and products from those markets received and used by American industries. John Bunker writes: “When we entered the war, the Merchant Marine, although still privately owned, came under government control. The men who sailed the ships were civilians, but they also were under government control and subject to disciplinary action by the U.S. Coast Guard and, when overseas, by local U.S. military authorities. Compared with soldiers and sailors, merchant seaman had much more freedom of movement. After completing a voyage, they could usually leave a ship but had to join another vessel within a reasonable period of time or be drafted into the U.S. Armed Forces. There was no uniform required for merchant seamen. Some officers wore uniforms; many did not. During the war, merchant ships were operated by some forty steamship companies, and the War Shipping Administration assigned new ships to them as they were completed. A total of 733 U.S.-flag merchant ships were lost during World War II. More than 6,000 merchant seamen died as the result of enemy action.”p12 U.S. Maritime Service personnel operated the 2,700 Liberty ships during World War II. The U.S. Maritime Service was the only service at the time with African American crew members serving in every capacity aboard ship. Seventeen Liberty Ships were named for African-Americans. Approximately 10%, 24,000, African Americans served in the Merchant Marine during World War II. During World War II the U.S. Merchant Marines moved war personnel and material under conditions shown above. The American Merchant Mariner’s memorial in Battery Park, New York City reads: "This memorial serves as a marker for America’s merchant mariners resting in the unmarked ocean depths." Poignantly the sailor in the water is covered twice a day at high tide. Installed in 1991 by sculptor Marisol Escobar designed based on a photo of the sinking of the SS Muskogee by German U-boat 123 on March 22nd, 1942. The photo was taken by the U-boat captain. The American crew all died at sea. Merchant mariners who served in World War II were denied veterans recognition and benefits including the GI Bill. This despite having suffered a per capita casualty rate greater then those of the U.S. Armed Forces. In 1988 a federal court order granted veteran status to merchant mariners who participated in World War II. On May 31, 1993, the Hudson River Maritime Museum received a brass plaque reading: “The United States Merchant Marine. This plaque is dedicated in memory of those who served in the U.S. Merchant Marine during W.W. II and in particular to those who did not survive “The Battle of the Atlantic”. Their dedication, deeds and sacrifices while transporting war material to the war shared their sacrifices and final victory, we, their surviving shipmates dedicate this memorial with the promise that they shall not be forgotten. Died 6,834. Wounded 11,000. Ship Sunk 833. P.O.W. 604. Died in Prisoner of War Camps 61. American Merchant Marine Veterans – May 31, 1993.” Today, the Maritime Administration (MARAD) is the Department of Transportation agency responsible for the U.S. waterborne transportation system. Founded in 1950 the mission of MARAD is to foster, promote and develop the maritime industry of the United States to meet the nation’s economic and security needs. MARAD maintains the Ready Reserve Fleet, a fleet of cargo ships in reserve to provide surge sea-lift during war and national emergencies. A predecessor of the RRF, the Hudson River Reserve Fleet of World War II ships, popularly referred to as the Ghost Fleet, was in the Jones Point area from 1946 to 1971. More about the Maritime Administration including a Vessel History Database can be found here: https://www.maritime.dot.gov/ United States Merchant Marine TrainingModern day training of merchant marines is held at seven academies, two of which U.S. Merchant Marine Academy and SUNY Maritime College, are in New York State. The U.S. Merchant Marine Academy, Kings Point, NY (USMMA) is one of the five United States service academies. When the academy was dedicated on 30 September 1943, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, noted "the Academy serves the Merchant Marine as West Point serves the Army and Annapolis the Navy." USMMA graduates earn:

USMMA graduates fulfill their service obligations on their own, providing annual proof of employment in a wide variety of MARAD approved occupations. Either as active duty officers in any branch of the military or uniformed services, including the Public Health Service and the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration or entering the civilian work force in the maritime industry. State-supported maritime colleges: There are six state-supported maritime colleges. These graduates earn appropriate licenses from the U.S. Coast Guard and/or U.S. Merchant Marine. They have the opportunity to participate in a commissioning program, but do not receive an immediate commission as an Officer within a service.

More information about the U.S. Merchant Marines can be found here:

If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

0 Comments

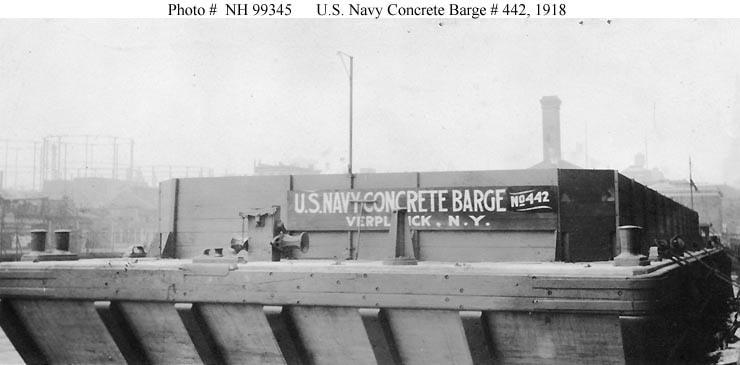

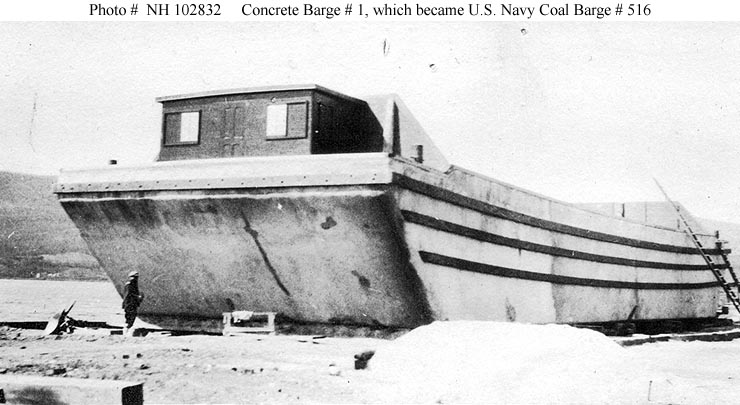

itle: Concrete Barge # 442 Description: (U.S. Navy Barge, 1918) In port, probably at the time she was inspected by the Third Naval District on 4 December 1918. Built by Louis L. Brown at Verplank, New York, this barge was built for the Navy and became Coal Barge # 442, later being renamed YC-442. She was stricken from the Navy Register on 11 September 1923, after having been lost by sinking. U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph. Hiding away in Rondout Creek, New York at 41.91245, -73.98639 is the last known surviving example of a World War I Navy ‘Oil & Coal’ Barge. It is less than a kilometer up the Rondout Creek from the Hudson River Maritime Museum. Based on a lot of ‘Googling’, it seems probable this is the first time that the provenance and history of this particular relic of concrete shipbuilding in the United States during the World War I era has been recognized. [Editor's Note: The concrete barge is featured on the Solaris tours of Rondout Creek.] The hulk is, in fact, the initial prototype of a ‘Navy Department Coal Barge’, concrete barges that were commissioned by the Navy Department : Bureau of Construction and Repair. This was the department of the U.S. Navy that was responsible for supervising the design, construction, conversion, procurement, maintenance, and repair of ships and other craft for the Navy. Launched on 1st June 1918, the ‘Directory of Vessels chartered by Naval Districts’ lists ‘Concrete Barge No.1’, Registration number 2531, as being chartered by the Navy from Louis L. Brown at $360 per month from 11th September 1918. In Spring 1918, the Navy Department had commissioned twelve, 500 Gross Registered Tonnage barges from three separate constructors in Spring 1918 to be used in New York harbour.  Navy Barge #516 which was the first prototype. It is believed that the barge at Rondout Creek is this particular barge based on the subtly different lines of her bow. Possibly photographed when inspected by the Third Naval District on 5 April 1918. She was assigned registry ID # 2531. This barge, chartered by the Navy in September 1918, was returned to her owner on 28 October 1919. While in Navy service she was known as Coal Barge # 516. U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph. AuthorsRichard Lewis and Erlend Bonderud have been researching concrete ships worldwide for many years. They have identified over 1800 concrete ships, spanning the globe, of which many survive. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Long Island’s coastal waters are rich in maritime history. Some stories are well known, others lesser known, and some waiting to tell their tale. In 2020, a friend, knowing I enjoyed local history, showed me an undated black and white photo of two surplus U.S. Navy boats in a cove off of Shore Road, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. The area is presently Eagle Dock Beach. I was intrigued with the boat stenciled 182 on her bow and began my research. Perhaps from watching the movie PT109 and building the model boat as a child, I initially presumed it was a Patrol Torpedo boat, but I learned that very few survived their service. Utilizing the website, Navsource, I forwarded the photograph and they provided me with a link to SC182, a World War I Submarine Chaser. The webpage included: photos from the Naval History and Heritage Command of the first crew, the boat serving in the North Atlantic and returning to the United States. The SC-1 class of 77 ton, 110’ submarine chasers, affectionately known as the Splinter Fleet, had a crew of two officers and 18 sailors. Powered by three, six cylinder 220hp engines, with a speed of 18 knots, they had a range of 1,000 nm. Four 600 gallon fuel tanks would “cover just a third of an Atlantic crossing, the 200+ subchasers … were either towed or accompanied by escorts with fuel and provisions.”[1] Armament included a 3”/23 caliber gun, two .30 caliber Colt machine guns and depth charges. They featured that latest in hydrophone sensors to detect German U boats. With the major shipyards tasked with building the larger vessels, smaller boat builders, already skilled at crafting wooden boats, were called upon to build the chasers. SC182 was constructed by International Shipbuilding Company in Nyack, NY and delivered to the U.S. Navy on May 6, 1918.[2] She arrived at Inverness, Scotland on April 24, 1919 and eventually saw service with the North Sea Minesweeping Detachment.[3] Three years later, SC182 was sold on June 24, 1921 from the Third Naval District Supply Depot, South Brooklyn, NY with an appraised value of $11,400.[4] For prospective buyers, the Sale of Navy Vessels catalogue included plans on how the chasers could be converted to yachts or fishing vessels. From the angle the photo was taken, the bow of another boat is partially obstructed, leaving only her last number “3” visible. The South Brooklyn location sale catalogue lists only one chaser for sale with an ending number of “3”… SC43.[5] Records indicate that both 182 and 43 were sold to Joseph G. Hitner of Philadelphia, P.A. Henry A. Hitner's Sons Company (later Hitner Industrial Dismantling Company) purchased many surplus Navy vessels; converting some to merchant ships while scrapping others.[6] A 1947 aerial photograph from the Suffolk County (NY) GIS website shows the boats in the cove[7] and again in 1953.[8] Interestingly today at low tide, remnants of a relatively large, wooden-planked boat, partially buried in silt, become visible in the tidal wetlands, proximate to the submarine chasers location. Could this be SC182 or her sister boat SC43? Perhaps. While this may never be confirmed, it is certain SC182, and possibly SC43, spent some of their last days here. More information about WW1 submarine chasers can be found in the book, Hunters of the Steel Shark: The Submarine Chasers of WW1 by Todd A. Woofenden. Footnotes: [1] https://unwritten-record.blogs.archives.gov/2016/04/26/spotlight-submarine-chasers/ [2] http://shipbuildinghistory.com/shipyards/emergencysmall/international.htm [3] www.subchaser.org/sc182 [4] www.subchaser.org/sale-of-vessels-14 [5] www.subchaser.org/sc43 [6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_A._Hitner%27s_Sons_Company [7] https://gisapps.suffolkcountyny.gov/gisviewer/ [8] https://www.historicaerials.com/viewer AuthorJames Garside appreciates local history. When a friend showed him an undated photograph of two US Navy boats taken locally, he was intrigued and wanted to identify and learn more about them. This article is the result of his research. It was originally published in the August 2023, Points East magazine. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's Note: This article was originally published in Ships and the Sea magazine, Fall 1957. The language, spelling and grammar of the article reflects the time period when it was written. Learn more about Liberty Ships here. What could be done with the outmoded Liberty ships in the event of an emergency? The Maritime Administration is proving they can be turned into assets. During World War II, pressed by the dire need of the national emergency, U.S. shipyards produced thousands of merchant ships. During this era, even the most lubberly of land-lubbers came to hear of that famous-type ship, the Liberty. Shipyards on all coasts of this nation made headlines with the fantastic speed with which these large oceangoing vessels were constructed. The average time for the completion of a Liberty was an amazing 62 days! By the time the building program had been completed, some 2600 standard Liberty ships had splashed into the water and taken up their vital task of delivering war material overseas. This tremendous fleet had a carrying capacity of almost 30 million tons. But what has happened to this vast fleet of Libertys in the postwar era? Have their bluff-bowed and full-bellied forms, and their 2500-horsepower reciprocating engines which produced speeds of only 11 knots, managed to survive the competition of cargo vessels with speeds up to 20 knots? The best answer to that may be a blunt statistic – some 1400 Liberty ships are tied up in the U.S. Maritime Administration's reserve fleet sites in rivers and bays around our coastline. This figure, taken in conjunction with the fact that several hundred Libertys were lost due to enemy action and other causes, and that several hundred others have been converted to such speck-purpose vessels as colliers, oil tankers, troop transports, hospital ships, ammunition ships and training vessels, leaves us with but one conclusion – the Liberty is too slow and inefficient for modern shipping needs. Some Libertys, of course, are in operation, but these are mostly doing tramping duty under foreign flags or carrying bulk cargoes like grain, ore and coal. However, it is not the economic aspect of the outmoded Liberty which concerns the Defense Department and the Maritime Administration. Those 1400 Liberty ships in the reserve fleet are supposed to represent security in any future national emergency. In the last few years the conviction has been growing among these military experts that the Liberty ship in its present design does not really represent insurance in case of need. Can the Liberty, for example, keep up with the speeds of future convoys? Can the Liberty hope to elude atomic-powered, snorkel-type submarines with speeds under the water of, say, 20 knots? The answer is clearly "No." Even in the limited Korean emergency, very few Liberty ships were taken out of the reserve fleet in spite of the need. The faster (16-knot) Victory and C-type ships were taken out first. Then the Defense Department had to charter privately owned vessels. With these dismal facts confronting it, the Maritime Administration has now embarked upon and completed an experimental Liberty conversion program which proves that those 1400 ships still represent an enormous national asset. The program, using four ships, had as its objective the upgrading of the ships with regard not only to speed but also to over-all efficiency. Increasing the speed of the Liberty may sound, on paper, like an easy matter. Why not increase the horsepower and efficiency of the engines and build new streamlined bows to replace the bluff "ugly-duckling" bows? To be sure, this can be and has been done. The problems confronting the Maritime Administration, however, were not simple in deciding upon the extent of the alterations which should be made. It must be remembered, first, that to upgrade hundreds of Liberty ships quickly in case of emergency would require vast dry-docking facilities, a call for quantities of scarce steel, and a need for new and more efficient engineering equipment. There were other equally pressing problems of design. Could the war-built ships stand the pounding in heavy weather which the higher speeds would cause? The Liberty ships, as a matter of fact, have been quite prone to cracking, even at the lower speeds. It was apparent that the altered ships would have to be heavily strapped. Also, there were the problems of propeller vibration at higher revolutions per minute, greater stresses on the rudder, and the like. Defense authorities had indicated a desire for 18 knots for the upgraded Libertys, but were willing to settle for 15 knots as a minimum. The latter speed was finally selected in view of the numerous problems involved, although technically it is possible to obtain an 18-knot speed with an appropriately lengthened, strengthened, finer and more powerful ship. It was decided that one of the four ships, the Benjamin Chew, would have its speed increased to 15 knots merely by the expedient of installing 6000-horsepower steam turbines with no change in hull form. This was undertaken with some misgiving as to the seakeeping qualities of such a blunt form driven at a 15-knot speed. But the savings in steel and dry-docking capacity in an emergency dictated that the attempt be made. Early experience with the ship has, in fact, confirmed these misgivings to some extent since the ship has had difficulty in maintaining 15 knots in heavy weather. The rate of fuel oil consumption has also been relatively high. However, it has been proved that, if necessary, the Liberty in its original form can be driven at significantly higher speeds with a minimum of alterations. The second of the ships, the Thomas Nelson, has been given geared diesel engines with 6000 horsepower as well as a lengthened and finer bow. As expected, 15-knot speeds have been easily maintained with a very low rate of fuel consumption. It would appear that if time and facilities permit, this type of alteration is to be preferred over that of the Benjamin Chew. The third and fourth ships, in addition to having lengthened and finer bows, are also being used to pioneer a new type of prime mover for ships – the gas turbine. The John Sergeant is the first all-gas-turbine merchant ship in the world, although a few vessels have been fitted with gas-turbine engines combined with other types of power plants. A controllable pitch propeller, another innovation for large U.S. ships, is used in conjunction with the gas turbine. This enables the pitch of the propeller blades to be controlled from the navigating bridge. For those of our readers who are not acquainted with the principles by which a gas turbine operates, a brief description might be helpful. A gas turbine operates by first compressing air, then heating it before sending it to a combustion chamber where fuel is mixed with the air and burned. The resulting gas is expanded through turbine nozzles, thus providing the power to turn the propeller shaft. The gas turbine is claimed to produce high thermal efficiency with reduced size and weight of machinery. Low-cost bunker "C" fuel oil may be burned. The gas turbine will probably be most efficient in the 7500- to 15,000-horse-power range. The William Patterson, the last of the four conversions, went into service in mid-1957. She is equipped with a gas turbine, too, but it is of a somewhat different type from the Sergeant's. The latter has what is known as an "open-cycle" gas turbine, while the Patterson has a "free-piston" type. (in the free-piston machinery, the pistons are not connected to crank-shafts as is customary in other internal combustion engines. Instead, the air-fuel mixture is burned between opposed pistons which then spring apart, compressing air at both ends of a cylinder. The compressed air causes the pistons to bounce back, thus forcing the gas into the turbine.) The marine industry is watching with great interest to find, first, whether the gas turbine will produce a more efficient prime mover than the steam turbine or diesel drive and, second, to find which type of gas turbine is better from an over-all point of view. Another aspect of the Liberty ship conversion program deserves comment. The Maritime Administration is using the program to experiment with different types of cargo-handling equipment, the theory being that increased speed at sea is only part of the picture of more efficient utilization of ships, the time spent in port loading and discharging cargo being of equal importance. So we find that the Thomas Nelson, for example, is equipped with radically new cargo cranes of two different types. The Benjamin Chew has a conventional set of cargo booms but of an improved type. She also has a removable 'tween deck in No. 2 compartment. All in all, these four Liberty ships are vastly improved vessels from their 1400 sisters still resting in the reserve fleet. They are being operated on the North Atlantic run by the same operator, the United States Lines. This will ensure, as nearly as possible, the same weather and port conditions, so that the many differences among the ships can be evaluated to arrive at valid conclusions as to what the ultimate form of the converted Liberty prototype should be. Although the program has primarily been aimed at the objective of upgrading the reserve fleet of Liberty ships in time of national emergency, it is also proving of great value to U.S. ship operator. The new look in Liberty ships appears to be not only new but also very pleasing. AuthorThis article, written by John La Dage, appeared in the Fall 1957 issue of Ships and the Sea magazine. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

“The maintenance of a merchant marine is of the utmost importance for national defense and the service of our commerce.” President Calvin Coolidge “In peacetime, the U.S. Merchant Marine includes all of the privately owned and operated vessels flying the American flag – passenger ships, freighters, tankers, tugs, and a wide miscellany of other craft. Merchant Marine vessels ply the high seas, the Great Lakes, and the inland waters, such as the Chesapeake Bay and navigable rivers.” Heroes in Dungarees by John Bunker During the colonial period, businessmen and legislators realized that prosperity was connected to trade. The more shipment of imports and exports through colonial ports the more money there was to be made. Carrying American produced goods to market in American made and managed ships kept the money in American pockets. Formation of the United States Merchant Marine is dated to 1775 when citizens at Machias, Massachusetts (now Maine) seized the British schooner HMS Margaretta in response to receiving word of the Battles of Lexington and Concord. After the Revolutionary War American ships were no longer under the protection of the British empire. The new nation offered incentives for goods to be moved on American ships. Wars on the European continent turned attention away from American activity as U.S. ships opened up new trade routes in the early Federal period. The Empress of China reached China in 1784, the first U.S. registered ship to do so. American shipping and shipbuilding flourished in the early 1800s. The years between the War of 1812 and the Civil War saw the development of canal systems connect the western interior with seaport markets. “Those years saw the merchant marine rise to its zenith in terms of the percentage of American trade carried. Only in the aftermaths of World Wars I and II would its percentage of world tonnage stand as high.” America's Maritime Legacy by Robert A. Kilmarx Sail powered packet ships, carrying passengers, pushed their crews hard. There was money to be made in quick passages across to Europe and back. Clipper ships also relied on speed as they carried high value cargoes of silk, spices and tea across the Pacific and the slave trade across the Atlantic. The hybrid sailing ship/sidewheeler steamer Savannah’s 1819 Atlantic crossing, the first with a steam powered engine, signaled the start of the transition from sail to steam. The May 22 date for National Maritime Day commemorates the day Savannah set sail from Savannah, Georgia to England. The Savannah transported both passengers and cargo. More information about the SS Savannah is here: Restoration of the merchant marine after the disruption of the Civil War was a national political issue in 1872. The Republican party advocated adopting measures to restore American commerce and shipbuilding. Mail packets, carrying mail around the world were active in this period. Financial scandals were associated with mail packet contracts. Training sailors in an academic setting began in the last quarter of the 1800s, predecessors of the present day Maritime Academies. The period between the end of the Civil War in 1865 and the European outbreak of World War I was a dynamic time for shipping. American raw materials and agricultural products were shipped to world markets and products from those markets received and used by American industries. John Bunker writes: “When we entered the war, the Merchant Marine, although still privately owned, came under government control. The men who sailed the ships were civilians, but they also were under government control and subject to disciplinary action by the U.S. Coast Guard and, when overseas, by local U.S. military authorities. Compared with soldiers and sailors, merchant seaman had much more freedom of movement. After completing a voyage, they could usually leave a ship but had to join another vessel within a reasonable period of time or be drafted into the U.S. Armed Forces. There was no uniform required for merchant seamen. Some officers wore uniforms; many did not. During the war, merchant ships were operated by some forty steamship companies, and the War Shipping Administration assigned new ships to them as they were completed. A total of 733 U.S.-flag merchant ships were lost during World War II. More than 6,000 merchant seamen died as the result of enemy action.”p12 U.S. Maritime Service personnel operated the 2,700 Liberty ships during World War II. The U.S. Maritime Service was the only service at the time with African American crew members serving in every capacity aboard ship. Seventeen Liberty Ships were named for African-Americans. Approximately 10%, 24,000, African Americans served in the Merchant Marine during World War II. During World War II the U.S. Merchant Marines moved war personnel and material under conditions shown above. The American Merchant Mariner’s memorial in Battery Park, New York City reads: "This memorial serves as a marker for America’s merchant mariners resting in the unmarked ocean depths." Poignantly the sailor in the water is covered twice a day at high tide. Installed in 1991 by sculptor Marisol Escobar designed based on a photo of the sinking of the SS Muskogee by German U-boat 123 on March 22nd, 1942. The photo was taken by the U-boat captain. The American crew all died at sea. Merchant mariners who served in World War II were denied veterans recognition and benefits including the GI Bill. This despite having suffered a per capita casualty rate greater then those of the U.S. Armed Forces. In 1988 a federal court order granted veteran status to merchant mariners who participated in World War II. On May 31, 1993, the Hudson River Maritime Museum received a brass plaque reading: “The United States Merchant Marine. This plaque is dedicated in memory of those who served in the U.S. Merchant Marine during W.W. II and in particular to those who did not survive “The Battle of the Atlantic”. Their dedication, deeds and sacrifices while transporting war material to the war shared their sacrifices and final victory, we, their surviving shipmates dedicate this memorial with the promise that they shall not be forgotten. Died 6,834. Wounded 11,000. Ship Sunk 833. P.O.W. 604. Died in Prisoner of War Camps 61. American Merchant Marine Veterans – May 31, 1993.” Today, the Maritime Administration (MARAD) is the Department of Transportation agency responsible for the U.S. waterborne transportation system. Founded in 1950 the mission of MARAD is to foster, promote and develop the maritime industry of the United States to meet the nation’s economic and security needs. MARAD maintains the Ready Reserve Fleet, a fleet of cargo ships in reserve to provide surge sea-lift during war and national emergencies. A predecessor of the RRF, the Hudson River Reserve Fleet of World War II ships, popularly referred to as the Ghost Fleet, was in the Jones Point area from 1946 to 1971. More about the Maritime Administration including a Vessel History Database can be found here: https://www.maritime.dot.gov/ United States Merchant Marine TrainingModern day training of merchant marines is held at seven academies, two of which U.S. Merchant Marine Academy and SUNY Maritime College, are in New York State. The U.S. Merchant Marine Academy, Kings Point, NY (USMMA) is one of the five United States service academies. When the academy was dedicated on 30 September 1943, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, noted "the Academy serves the Merchant Marine as West Point serves the Army and Annapolis the Navy." USMMA graduates earn:

USMMA graduates fulfill their service obligations on their own, providing annual proof of employment in a wide variety of MARAD approved occupations. Either as active duty officers in any branch of the military or uniformed services, including the Public Health Service and the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration or entering the civilian work force in the maritime industry. State-supported maritime colleges: There are six state-supported maritime colleges. These graduates earn appropriate licenses from the U.S. Coast Guard and/or U.S. Merchant Marine. They have the opportunity to participate in a commissioning program, but do not receive an immediate commission as an Officer within a service. More information about the U.S. Merchant Marines can be found here:

If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's note: The following text was originally published in 1793 from the newspapers listed below. Thanks to volunteer researcher George A. Thompson for finding, cataloging and transcribing this article. The language, spelling and grammar of the article reflects the time period when it was written.  HMS "Iris" dismasted by the French Frigate "Citoyenne-Francaise" 13 May 1793. Thomas Luny, date unknown. Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons. While no images of the fight described in these reports are available, this scene depicts a similar combat between similar ships in 1793. Both are single-deck frigates engaging, with the British getting the worst of it. Note the tendency in naval engagements in the age of sail to target the rigging as much as possible to immobilize the target. British Orders to Engage the French Frigate received. "Boston", August 5. The master of a vessel lately arrived at Newport from Jamaica, on his passage spoke with Captain Courtnay, commander of his Britannic Majesty's frigate "Boston", of 32 guns, who informed him, that he had positive orders to cruise near the Sound until he met the French frigate "l'Embuscade" --------- Further accounts state, that the "Boston" had arrived at the Hook, and that the commander had sent up a challenge to Capt. Bompard, of the "l'Embuscade", and informed him that he should be there about three days in waiting for him, and that he wished much to see him. Capt Bompard was preparing to meet him. Diary; or, Loudon's Register, August 8, 1793, p. 3, col. 2 "L'Embuscade Frigate". We the subscribers do certify, are ready to make oath, if required, that have been hailed by, and obliged to go on board his Britannic Majesty's frigate the "Boston", on the 29th of July last, Capt. Courtnay, the commander thereof, requested us to inform Citizen Bompard (meaning the Captain of the French frigate "l'Embuscade") "That he would be glad to see -- and was then waiting for him," or words fully to that import. And we further certify that a mid-ship-man of the "Boston", who came in the boat with us until he was near Governor's-Island, assured us, "that the "Boston" was fitted out for the express purpose of fighting and taking the "Ambuscade"; and that Capt. Courtnay had on that account been permitted to take on board, at Halifax, as large a number of extra seamen, as he thought proper. Peter Deschent, C. Orset, Esq., Andrew Allen. Diary; or, Loudon's Register (New York, N. Y.), August 6, 1793, p. 3, col. 1 [the "Esq." added in pen] Challenge Issued! Capt. Dennis, of the United States revenue cutter "Vigilant", came up on Sunday evening from Sandy Hook: He informs us that at 4 P. M. of the afternoon of said day, 2 leagues E. by S. of the Hook, spoke the British frigate "Boston", of 32 guns, commanded by Capt. Courtnay, having in company with him a small schooner of 8 guns. -- Capt. Courtnay, informed Capt. Dennis he wou'd be very happy to see the French Republic's frigate "L'Embuscade", Citizen [?] Bompard, at any time within five days: -- (If we are to judge from appearances on board the "l'Embuscade", it is more than probably he will be gratified with a sight of her.) The following note was on the Coffee-house book yesterday afternoon: -- "Citizen Bompar's compliments wait Capt. Courtnay -- will meet him agreeable to invitation -- hopes to find him at the Hook to-morrow. -- dated Monday, July 29th. We hear that nine vessels are chartered by different parties for the Hook, in order to see the action between the "L'Embuscade" and the "Boston" frigate. Daily Advertiser (New York, N. Y.), July 30, 1793, p. 2, col. 5 - p. 3, col. 1 Challenge Accepted! Spectators Gather! FOR SANDY HOOK For the purpose of carrying Passengers. The beautiful and fast sailing Schooner "EXPERIMENT", Charles Buckley, Master, Will sail as soon as the French frigate "l'Embuscade" gets under way. For passage apply to the master on board. It is desired of those who wish for a passage to call by 10 o'clock. Said schooner lies at Jone's new Wharf. July 30. D Advertiser, July 30, 1793, p. 3, col. 1 Please insert the following, and oblige many of your customers: We hear that a number of boats are engaged, for the purpose of conveying some of the lovers of Royalty, who reside among us, on board His Most Gracious Majesty's Frigate "Boston", now cruising off Sandy Hook, to congratulate the Right Honorable Mr. Courtnay, on his safe arrival in these latitudes. The Whigs of New-York, will do well to mark those men who are most forward on this business, for it is too true, that we harbour miscreants among us, who will scarce treat a Frenchman with common civility in the street, and yet will go 40 or 50 miles to make obeisance to a titled Briton -- Mark these men, I say. DEMOCRAT. Diary; or, Loudon's Register (New York, N. Y.), July 29, 1793, p. 3, col. 1; When Citizen Bompard or the "l'Embuscade", received the invitation from the British Frigate, "Boston", for a visit at the Hook, he immediately put every thing in train to visit his honourable friend, Capt. Courtnay. Yesterday and the day before, all hands were busied on board the "l'Embuscade"; and being in complete order, she weighed anchor, at 5 o'clock this morning, and fell down with the tide, round the Battery and was obliged to anchor in the North River, the tide being spent, and the wind ahead; lay there till past three o'clock this afternoon -- It is expected she will weigh anchor in the course of the afternoon, and must beat down against the wind, he, and all hands on board, being eager to pay their respectful salutations to Capt. Courtney, who they say is impatiently waiting for Capt. Bompard. It is not thought improbable but that Capt. Courtney, with the "Boston", may visit New York before he leaves the coast; others wish that Capt. Bompard may visit Halifax, at the company of the French people is not well relished by some people here. How that may turn out, we may hear is two or three days. Some think, that as a fleet of French ships are hourly expected here from Baltimore, the visit my be interrupted. Number of gentlemen are gone to the Hook, as witnesses to the important visit of these two Commanders, belonging to the two greatest nations on earth. Diary; or, Loudon's Register (New York, N. Y.), July 30, 1793, p. 3, col. 3; The following LETTER was transmitted by Citizen BOMPARD, to Captain Courtnay, of the British frigate "Boston", on hearing that the latter "would be happy to see him at the Hook." "On board of the French republic's frigate, "L'Embuscade", 29th of July, 1793, the 2d year of the Republic. "SIR, "I have received an invitation by a sloop which you boarded yesterday, to sail out of this harbour and fight your frigate; I should not have hesitated a moment to comply with your wishes (which seems to me only ostensible) had you conveyed your challenge in the mode that honour prescribes. Upon an occasion of this kind, I should have written to the opposite commandant, and have pledged my honour, that I was unattended by any other armed vessell, and that I would not employ any artifice or strategem, unbecoming the character of a brave and candid soldier; as you have conducted yourself in a different manner, you must be sensible that I cannot consistently with my duty, expose the brave man I have the honour to command, on vague and unauthenticated reports. "Therefore, sir, if you are really the brave man, you pretend to be, pursue the above measures, and as soon as I receive your answer, shall do myself the honour of waiting upon you. (Signed.) BOMPARD, Captain-Commander of the "L'Embuscade "N. B. Citizen Bompard, having not received an answer to the above letter, resolved however not to disappoint the martial ardor of Captain Courtnay, and accordingly has sailed this morning out of the harbor to wait upon him." Grand Naval Combat. The following information is given us by one of the hands belonging to the Pilot Boat Hound, of this port: --- On Wednesday night last, about 8 o'clock, the pilot boat fell in with, to the southward of the Hook, the two frigates "L'Embuscade" and "Boston", standing on one course, and took a birth between the two until towards day light, when the boat sheered off out the reach of their guns, and lay to. After day light the "L'Embuscade" fired a gun and hoisted the National flag of France, which was shortly after hoisted by the British frigate. The "L'Embuscade" then bore down upon the "Boston", both ships being then between the Grove and the Woodlands, distant about 5 leagues S. E. of the Hook. The "Boston" endeavoured several times to get to windward of the "L'Embuscade", but not being able to accomplish her point, she was obliged to come to close action precisely at 37 minutes past five o'clock, A. M. The action continued from that time until half past seven -- during the course of which the "L'Embuscade's" colours were shot away, which induced our informant to suppose she had struck, but shortly hoisted them again. In a little time the same accident happened to the "Boston", which was as soon replaced. The "L'Embuscade" attempted to board the "Boston", but failed. About 7 o'clock the fire from the "L'Embuscade" was somewhat slackened, but seemed to be renewed from the "Boston", when a shot from the "L'Embuscade" struck the main-top-mast of the "Boston", and carried it overboard; on which she immediately ceased firing, crouded all the sail she could and ran off -- the "L'Embuscade" fired three guns more at her as a token of Victory, and as soon as she could get underway to follow the "Boston", of which she was delayed in about half an hour, owing to her rigging and sails being very much mutilated) she gave her chace, which out informant assures us she continued till past nine o'clock, when both ships were out of sight. --- They were both steering to the southward. (The above account is corroborated by the information of another person who was on board the pilot boat "Hound", and saw the whole action very distinctly with the naked eye.) Daily Advertiser (New York, N. Y.), August 2, 1793, p. 3, col. 1; Another Account. Thursday morning, August 1st, 1793, on board sloop "Friendship", Capt. Peterson, (a Newport Packet.) AT 6 o'clock, A. M. distant four miles from the Hook. Got under way immediately and sailed towards the vessels; at half past 6 o'clock, discovered them to be engaged a cable's length assunder, at 45 minutes past 6 o'clock saw the windward ship (the "L'Embuscade") had lost the fore-top-sail-tie. Both ships standing W at 50 minutes past 6 o'clock, the leeward ship "Boston" lost her main-top-mast, and the head of her main-mast also apparently carried away. At 55 minutes past 6 o'clock, the firing ceased, both ships appearing to be repairing their damages, when the "Boston" bore off, before the wind (S. W.) At 8 minutes past 7 o'clock the "L'Embuscade" bore down to engage again. 20 minutes past 7, saw the British union flying in the mizen shrouds of the crippled ship -- the national colours flying at the mizen peak of the "L'Embuscade". At 35 minutes past 7 o'clock saw the "Boston", with studding sails alow and aloft, making every effort to get off -- The "L'Embuscade" still repairing, but making what sail she could to follow. At 8 o'clock the "Boston", under full sail still, was about a league a head of the "L'Embuscade", steering S. W. about 9 knots an hour; The latter carrying a foresail, a fore-topsail a foretop-gallant-sail, main-top-sail and mizen-topsail set, the main sail loose. At 20 minutes past 8 o'clock, . . . the ships 1 1-2 league asunder, the "L'Embuscade having set her bower studding sails; at 33 minutes past 9 o'clock, could just discern the "L'Embuscade"; at 50 minutes past 9 o'clock, discerned the "Boston", from the mast head, the "L'Embuscade" still pursuing, and overhawling the "Boston". Diary; or, Loudon's Register (New York, N. Y.), August 2, 1793, p. 3, col. 4 French Fleet. Last Evening, the French Fleet which has been so long expected from the Chesapeake, arrived in this port, consisting of 15 sail. On their approach toward the city, the citizens, to the number of several thousands, collected on the battery, to welcome them to our port. After they had come to anchor off the battery, the Admiral, accompanied by several other officers, came on shore in the barge, and waited on his Excellency the Governor, at the government house; a few moments after which the Admiral's ship fired a salute, which was immediately answered from our battery, with three cheers from the amazing concourse attending. L'Embuscade Frigate. What greatly added to the beauty of this scene was the arrival of the "L'Embuscade", from her cruise -- as she approached, the people assembled were at a loss how to express their joy, having heard of the gallant behavior of Citizen Bompard, the commander, and his crew -- continued shouts and huzzas were vociferated, which were returned from on board, until she had passed into the East River. We have just learnt, that only 7 men were killed, and 10 wounded in the engagement, which was incessant for three glasses, in which time both ships were much burnt in their rigging, and the main top mast of the "Boston" was carried away before the wind, was pursued by the "L'Embuscade", but out sailing her, the "L'Embuscade" abandoned her fell in with, and took a Portuguese brig, richly laden, and has thus safely arrived to the Universal joy of their brethren in this city. A great variety of accounts have been handed the public on the subject of the battle between the "L'Embuscade" and "Boston", all of which agree, that the arrogant Capt. Courtnay, of the "Boston", received a most severe drubbing from the gallant Captain Bompard, of the "L'Embuscade". Diary; or, Loudon's Register (New York, N. Y.), August 3, 1793, p. 3, col. 1, from N-Y Journal We are favored through a Correspondent with the following relation of the late action between the frigates "L'Embuscade" and "Boston" given by an Officer who was on board the former of these ships. "Though the Challenge given by Capt. Courtnay to Capt. Bompard, on the 29th ult. has become a topic of common conversation, I mean not to enter into a discussion of the propriety or impropriety thereof, but only state facts, leaving each candid Republican in this Land to decide as he thinks proper, on the final event. I cannot help observing that on the morning of the day when the challenge was received, the Crew of the "L'Embuscade" had been permitted to make a holiday; notwithstanding which, as soon as they received information of this uncommon and unexpected summons, assembled with a distinguished cheerfulness and zeal, worthy of the cause in which they were engaged; for, though the situation of the frigate would on common occasions have required the work of three days to fit her for sea, she nevertheless, by their extraordinary exertions, weighed anchor in twenty-four hours. Owing to contrary winds, we did not reach Sandy-Hook till the 31st ult. at two o'clock, P. M. when the Captain ordered to steer to the eastward, in anxious expectation of seeing his antagonist at the place of rendezvous, but we did not find him there. Capt. Bompard, stimulated by the natural feelings of a soldier, to gratify Captain Courtnay in his wish, steered on the eastward five leagues farther, in hopes of meeting this new champion of chivalry, and at four in the morning of the 1st of August, having then our larboard tacks on board, seeing at the same time an English brig, at which we fired a gun, and hoisted our national colours, when the brig wore and hauled her wind, on the same tack with the ship, which we were then convinced was a frigate, with French colours flying. On this, Captain Bompard ordered the private signal to be made, which not being answered by the other, left no room to doubt that she was our challenging rival. In our approach to each other, the Boston endeavored to get to windward, but without success, at last we got so close, that Captain Courtnay relinquished his disguise, substituting in its room, the royal colors. This was at three-quarters past five, when Captain Bompard in his jacket, came forward, and sundry times, in a very loud voice, called Captain Courtnay by name, who, instead of a common reply, very politely answered with a broadside. A Thousand Huzzas! A Thousand cries of Vive la Republique Francoise! announced to the Georgists of Halifax, the impression which their royal artillery made on the hearts of Republicans!!! The crew of the "Boston" was silent, and the netting prevented us seeing the face of her noble Commander. The "L'Embuscade" permitted the "Boston" to shoot ahead, and then attempted to put about, but missing stays, continued on the same tack. The "Boston" then wore, when the "L'Embuscade" backed her main and mizen topsail, and as she passed began her fire; it was not quick, but time will probably prove that it was well directed. The fight continued till three quarters past seven, when a shot carrying away the "Boston's" main top-mast, she instantly wore and made tail before the wind. She must have suffered severely, and we were so much crippled in our masts and rigging, our braces, bowlings, &c. being cut to pieces, that it was some time before we could wear, not could we work the ship with the same dispatch the enemy did. The enemy by this means had gained a considerable distance from us, being still before the wind with all the sail she could possibly crowd; but we found that the state of our masts would not admit of a press of sail, we nevertheless continued the chase till 11 o'clock, when seeing that we had no chance of coming up, and discovering at same time a Portuguese brig, within two miles of the "Boston", we made sail after and captured her, as a proof of our victory and the enemy's defeat We then hove to till the necessary repairs were completed, and afterwards made the best of our way for New-York. We had seven men killed in action, and fifteen wounded. Our people say, they was a number of men thrown overboard from the English frigate; their wounded we have great reason to believe are numerous, as our fire, during the whole of the action, was directed with that deliberate coolness, characteristic of Republican valor. The fire of the "Boston" did much more damage to our rigging than to our hull, and . . . in contradiction to the rules of war, generally adhered to by civilized nations, they fired at us a quantity of old iron, nails, broken knives, broken pots, and broken bottles -- a mode of warfare with which their enemy was then, and I hope ever will be unacquainted. It may be proper to mention, that Capt. Bompard endeavored to board the enemy, in which case broken bottles would have proved of little service, but this the British Captain prudently avoided; whether, when all the circumstances of the challenge are taken into view, his nation will promote him for this act of wisdom: I cannot say, it would be difficult to say, whether the cool deliberate courage, or the innocent cheerful gaiety of the citizens of the "L'Embuscade", was most conspicuous during the engagement. Those who had never been in action before, were astonished to behold what little effect a broad side was attended with. I will say nothing of our intrepid Captain, it would be doing him an injury to attempt his praise. Our ship's colours, torn as they were at the close of the action, have been presented to the Tammany Society of this city, as a token of that respect which those virtuous patriots merit, in our opinion, from their Republican Brethren of France. Diary; or, Loudon's Register, August 6, 1793, p. 3, cols. 1-2; PHILADELPHIA, August 2. "L'EMBUSCADE" FRIGATE. Extract of a letter from a gentleman at Long Branch to his friend in this city, dated August 1, 1795. "This morning we were gratified with the view of an action between "L'Embuscade" and an English frigate of about the same size, which is said to have come from Halifax, on purpose to attack her. The action began at about half after five this morning, and lasted till near seven, the firing was tremendous, and both vessels during the action appeared at time to be much in confusion. At length the French ship shot away the main-top-gallant mast of the English man, and that shot appeared to decide the fate of the battle, for she immediately bore off. The "L'Embuscade" had her sails clued up, and appears willing to attack, provided the other does not run away. She has, however, beat the English ship completely. Daily Advertiser, August 6, 1793, p. 2, col. 3 New-York, August 3. About 7 o'clock last evening came up and anchored in the East river, amid the repeated huzzas of the citizens of New-York, the French frigate "L'EMBUSCADE". We have been enabled only to gain a few particulars of the action between her and the "Boston", for this day's paper -- the whole of which we hope to lay before our readers on Monday: It appears that the action commenced about the same time, and ended in nearly the same manner as mentioned in our paper of yesterday -- that the "l'Embuscade" chased the "Boston" about five hours to the Southward, when owing to the shattered condition of her sails and rigging, and espying a Portuguese Brig off, she gave over chasing the "Boston" frigate, and pursued the Brig which she captured and brought to this city. The Frigate "L'Embuscade" had six men killed and twelve men wounded, but they supposed the number of killed and woulded on board the "Boston" must have been much more, as they saw her throw 21 bodies overboard during the chase; her pumps were kept constantly going. It is supposed Capt. Courtnay is among the slain. The "L'Embuscade's" masts are so full of shot holes that she will be obliged to replace the whole with new ones. General Advertiser (Philadelphia, Pa.), August 6, 1793, p. 2, col. An English visitor's account The day of my first arrival in New York was rendered memorable by the severe engagement which took place off Sandy Hook, between the "Boston" and the "Ambuscade". We heard distinctly the broadsides as we passed down Long Island Sound, but knew not on what account they were fired. This battle being premeditated on the part of the French, various were the conjectures respecting the cause, and I therefore took some pains to gain correct information. The "Ambuscade", a large 44 gun frigate, had been some time lying opposite to New York, and it was known that the "Boston" was stationed on the outside of Sandy Hook. Captain Bompard, who commanded the "Ambuscade", had given no intimation of his intended departure, until, on a sudden, preparations were made to go out, and a report was spread that Captain Courtenay, the British commander, had sent him a challenge. The circumstance which gave rise to the report was this: A pilot-boat had carried some provisions to the "Boston", and as the pilot was returning down the side of the ship to his boat, a young midshipman said to him, "give our compliments to Captain Bompard, and tell him we shall be glad of his company on this side the Hook." This lost nothing by the way in being communicated to the French commander, who was even told that it was a direct challenge from Captain Courtenay. It soon spread over New York, and the French faction began to feel ashamed that their ship should be blockaded, and thus challenged to come out, by an enemy so inferior in force. This was a spur to Bompard, who, having taken on board a number of American seamen that had offered themselves as volunteers, he promised to chastise the haughty foe. He accordingly went out, attended by a great number of vessels and boats crowded with Americans to witness the fight. The "Boston" soon descried the enemy, and was observed to alter her tacks and to prepare for battle, which soon began on the part of the French, while her antagonist waited her neared approach. The Gallic-Americans assembled on the occasion had already begun to persuade themselves that the little "Boston" was declining an engagement, when she opened a tremendous and incessant fire. I was informed, so rapid were her broadsides, that she gave three to two received from her enemy during the whole engagement. In the heat of battle the brave Captain Courtenay was killed, and the first lieutenant of the "Boston" badly wounded. The latter, having passed through the surgeon's hands, was brought on deck, and proved an able substitute for his deceased captain during the remainder of the bloody conflict. The mainmast of the "Ambuscade" was shot through, and could barely be supported by the shrouds -- a breeze would have carried it by the board. The "Boston" having lost her fore-top-mast, she put about to replace it, and soon after descrying the French fleet from St. Domingo, she made sail towards Halifax, while the "Ambuscade" declined following, happy, no doubt, in getting back. The Democrats set up the cry of victory, and they publicly rejoiced at what I thought a discomfiture. Next morning I mixed among a group going on board the "Ambuscade", and there, for the only time, saw the horrid issue of battle. The decks were still in parts covered with blood -- large clots lay here and there where the victim had expired. The mast, divested of splinters, I could have crept through; and her sides were perforated with balls. I shrunk from this scene of horror, though amongst the enemies of my native country. The wounded were landed, and sent to the hospital. I counted thirteen on pallets, and double that number less severely wounded. Nothing but commiseration resounded through the streets, while the ladies tore their chemises to bind up the wounds. Advertisements were actually issued for linen for that purpose, and surgeons and nurses repaired to the sick ward. The French officers would not acknowledge the amount of their slain. I calculate the proportion to the wounded must have been at least twenty. I afterwards went on board the "Jupiter", a line of battle ship, and one of the St. Domingo squadron. The sons of equality were a dirty ragged creww, and their ship was very filthy. I witnessed Bompard's triumphal landing the day after the engagement. He was hailed by the gaping infatuated mob with admiration, and received by a number of the higher order of Democrats with exultation. They feasted him, and gave entertainments in honour of his asserted victory. He was a very small elderly man, but dressed like a first-rate beau, and doubtless fancied himself upon this occasion six feet high! At this moment I verily believe the mob would have torn me piecemeal had I been pointed at as a stranger just arrived from England. I ground this supposition on the fact of a British lieutenant of the navy having been insulted the same day at the Tontine coffee-house; but he escaped farther injury by jumping over the iron railing in front of the house. The flags of the sister republics were entwined in the public room. Some gentleman secretly removed the French ensign, on which rewards were offered for a discovery of the offender, but he remained in secret. Charles William Janson. The Stranger in America. London, 1807. pp. 428-31. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

In honor of the attacks on the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001, we are sharing one of our favorite and most poignant documentary films about that day, "Boatlift." "Boatlift" chronicles the marine evacuation of lower Manhattan during the attacks. Narrated by Tom Hanks, this short film highlights the ordinary people who stepped up to help strangers in a time of crisis. If you would like to learn more about the evacuation and the people involved, read Jessica DuLong's book Saved at the Seawall: Stories from the September 11 Boat Lift or catch up on her 2021 lecture for the Hudson River Maritime Museum, "Heroes or Human: September 11th Lessons on the 20th Anniversary," as recorded below. Jessica DuLong shares the dramatic story of how the New York Harbor maritime community delivered stranded commuters, residents, and visitors out of harm’s way on September 11, 2001. Even before the US Coast Guard called for “all available boats,” tugs, ferries, dinner boats, and other vessels had sped to the rescue from points all across New York Harbor. In less than nine hours, captains and crews transported nearly half a million people from Manhattan. This was the largest maritime evacuation in history. DuLong’s talk, and her book Saved at the Seawall, highlight how people come together, in their shared humanity, to help one another through disasters. Actions taken during those crucial hours exemplify the reflexive resourcefulness and resounding goodness that reminds us of the hope and wonder that’s possible on the darkest days. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Happy Fourth of July! For today's Media Monday, we thought we'd share this amazing series of videos with leading historians on the American Revolution in the Hudson River Valley, centered on Dobbs Ferry. Two major turning points of the American Revolutionary War occurred in the Hudson River Valley - the American victory at Saratoga (October, 1777) and the bold decision of Washington and Rochambeau to march from Westchester County, NY, to Virginia (August, 1781). In 2009 the Dobbs Ferry Historical Society received a grant to record a series of interviews with leading historians of the American Revolution as part of the creation of the Washington-Rochambeau National Historic Trail (now known as the Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route). These excerpts are just a few of the ten part video series! Interview with Pulitzer Prize winning historian, David Hackett Fischer: During the American Revolutionary War Washington and Rochambeau, while encamped in Westchester County, NY, made the decision that would win the war. Dr. Fischer speaks about this decision and about Dobbs Ferry, starting point for Washington's 1781 march to victory at Yorktown, Virginia. Congress recognized the great historic significance of the march by establishing the Washington Rochambeau National Historic Trail in 2009. Dr. Fischer explains why Washington chose lower Westchester (Dobbs Ferry, Ardsley, Hartsdale, Edgemont and White Plains) for the side-by-side encampment of the American and French armies and why he deployed the light infantry and light dragoons in Dobbs Ferry. In this interview Thomas Fleming, past president of the Society of American Historians, speaks about the 1781 encampment of the American and French armies in lower Westchester (Dobbs Ferry, Ardsley, Hartsdale, Edgemont and White Plains) and about the the march of the American army from Dobbs Ferry to victory at Yorktown, Virginia. Dr. Mary Sudman Donovan, author of George Washington at 'Head Quarters, Dobbs Ferry', discusses topics relating to the Washington Rochambeau encampment of the allied American and French armies in Dobbs Ferry and neighboring localities (July and August, 1781). You can watch all ten videos on the Dobbs Ferry Historical Society YouTube Channel! To learn more about the Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route, visit the National Parks Service. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

The rapid decline of sail freight in the early 20th century was not entirely due to technological advantages of steam and motor propulsion, or to economics, but another outside force: Submarine Warfare. The First World War raged from 1914 to 1918, and was the first truly mechanized war. The submarine made its debut as a weapon in this conflict, and the German U-Boats became notorious for their damage to allied shipping. Since submarines were new, there were few developed techniques for countering them. By the end of the war the Office Of Naval Intelligence had created a small handbook on the subject: The main recommendations were to use a vessel's superior speed first, to reduce time in the war zone, and to maneuver unpredictably if a speed over 16 knots could not be maintained For windjammers, 16 knots is a very high speed in most conditions, and changing course by 20-40 degrees every 10-20 minutes is difficult or impracticable, depending on the winds available. Their relatively small size made arming them with sufficiently powerful naval guns difficult, and there weren't enough small guns to go around even if they could be mounted around the ship's rigging. According to Lloyd's of London Casualty Lists, some 2,000 windjammers of over 100 tons were sunk during the War, over a third more than in the 5 years before the war., and this does not count ships damaged but not sunk. Dozens of others under this threshold were also sunk or damaged by submarines. As a result, the already slowly declining sail fleets suffered a catastrophic loss of vessels and trained crew. Further, due the importance of speed in avoiding or evading U-Boat attacks, steamers and motor vessels became the primary means of replacing ships lost during the war. The larger, faster vessels were more survivable, and could take up the shipping capacity lost faster than building another large fleet of relatively small wind-powered vessels. Those windjammers which survived the First World War carried on, especially in coastal trade, until the 1930s and some areas continue to do so today. However, losses in the First World War reduced the world's transoceanic windjammer fleet to a very low number, while economics favored the new, very large steamers on all but the longest routes. For more reading about the use of U-Boats off the US Coast in the First World War, try out the Navy's publication on the subject from 1920 for many detailed accounts and information. This Memorial Day, keep the windjammer sailors of a century ago in mind. AuthorSteven Woods is the Solaris and Education coordinator at HRMM. He earned his Master's degree in Resilient and Sustainable Communities at Prescott College, and wrote his thesis on the revival of Sail Freight for supplying the New York Metro Area's food needs. Steven has worked in Museums for over 20 years. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

The Hudson River Maritime Museum recently received a set of black and white photographs documenting the work of the Kingston Shipbuilding Corporation during World War I. Clyde Bloodgood worked at the shipyard located on Island Dock. Shipbuilding has been going on for the last couple of hundred years along Rondout Creek. William duBarry Thomas writes in the 1999 Pilot Log: "During World War I, the Kingston Shipbuilding Corporation constructed ocean-going wooden-hulled cargo steamships (the only vessels of the type ever built along the Creek)" The museum is grateful for the donation of these fine photographs. They are a wonderful addition to the museum's collection and aids in our ability to tell the history of the Hudson River and its tributaries. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

|

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 [email protected] Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |