History Blog

|

|

|

|

|

On Tuesdays the Hudson River Maritime Museum will share interesting images from its collection. We hope you enjoy these brief forays into the past!  The merry-go-round at Kingston Point Park, from a postcard circa 1906. A ferris wheel was the other amusement ride at the park. Mostly people strolled around, ate picnic lunches at tables scattered throughout the park, and listened to the band playing in their bandstand in the lagoon. Hudson River Maritime Museum Collection Kingston Point Park was built as a steamboat landing, amusement park, and gardens in the 1890s. Featuring a trolley station and Ulster & Delaware Railroad Station nearby, Kingston Point Park served as a central hub for tourists and travelers to come to Kingston in the early 20th century. For decades the Hudson River Day Line had docked primarily at Rhinecliff, and visitors to Kingston had to use the ferry to cross the river. But Samuel Coykendall, president of the Thomas Cornell Steamboat Company, saw the potential of Kingston Point. Coykendall was also involved in the Ulster & Delaware Railroad, and many passengers were coming to Kingston to go to the Catksill Mountain Houses, so taking the railroad to their final destination was obvious. Opened in 1896, the landing was soon populated with a hotel, amusement park rides (like the above merry-go-round carousel), boat rentals, bandstand, and more. But by 1928, nothing was left. The short-lived landing has left hundreds of postcards and photographs evoking the romance of the heyday of steamboat tourism in the Hudson River Valley.

If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

0 Comments

In 1976, the year of the Bicentennial, folksinger Pete Seeger and songwriter Ed Reneham released the album Fifty Sail on Newburgh Bay. Designed as a fundraiser for the Hudson River Sloop Restoration, Inc. group, which would later becomes Clearwater, the album featured a number of traditional and original songs about the history of the Hudson River and other New York waterways. Recorded in Woodstock that summer and released in October, 1976, the album features Pete Seeger and Ed Reneham.

This particular song, "Hudson River Steamboat" has a murky history, but appears to be a traditional tune. In the liner notes for Fifty Sail on Newburgh Bay, William Gecke, lyricst for five of the original songs, wrote that "Hudson River Steamboat" was performed "as learned from John and Lucy Allison."

"Hudson River Steamboat" Lyrics

Hudson River steamboat, Steamin’ up and down. New York to Albany Or any river town. Choo-choo to go ahead, Choo-choo to back ‘er. Captain and the first mate, They both chew tobacker. Oh, choo-choo to go ahead, choo-choo to slacker. Packet boat, towboat, and a double-stacker. Choo-choo to Tarrytown, Spuyten Duyvil all around. Choo-choo to go ahead, choo-choo to back’er Shad boat, pickle boat, lyin’ side by side. Fisherfolk and sailormen waitin’ for the tide. Raincloud, stormcloud over yonder hill. Thunder on the Dunderberg the rumble’s in the kill. Oh, choo-choo to go ahead, choo-choo to slacker. Packet boat, towboat, and a double-stacker. Choo-choo to Tarrytown, Spuyten Duyvil all around. Choo-choo to go ahead, choo-choo to back’er. The Sedgwick was racin’, and she lost all hope. Used up her steam on the big calliope. She was hoppin’ right along, she was hoppin’ quick, All the way from Stony Point to Popalopen Creek. Oh, choo-choo to go ahead, choo-choo to slacker. Packet boat, towboat, and a double-stacker. New York to Albany, Rondout and Tivoli. Choo-choo to go ahead, choo-choo to back’er. Oh, choo-choo to go ahead, choo-choo to slacker. Packet boat, towboat, and a double-stacker.

The General Sedgwick was a steamboat built in Jersey City in 1862 and was one of the last to be equipped with a steam calliope. If you have heard the organ-like music on an old-fashioned steam-powered carousel, you have an idea of what a steam calliope sounds like, but you can also listen to one here.

Few calliopes were installed on Hudson River steamboats for one primary reason - sometimes they took all the steam! So the lyric, "The Sedgwick was racin’, and she lost all hope. Used up her steam on the big calliope," is a reference to using too much steam to make music, leaving too little to propel the engines. Calliope music could be heard for miles and although it must have been quite loud aboard, the sound was nonetheless much-beloved by New Yorkers. In the 1880s, the Sedgwick was renamed the "Bay Queen" and by the early 1900s was lying in wreck at Ward's Point, Staten Island. If you'd like to hear a steamboat with a steam calliope in person, you can visit Lake George and take a ride aboard the Minnehaha, or listen to this great video of the Minne playing her calliope in a duet with its echo!

If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's Note: This article from the July 20, 1767 issue of the New York Mercury newspaper gives an indication of what it was like to stock up on supplies when sloops sailed on the Hudson River in the 1760s. See more Sunday News here. The Subscriber, a Boatman, who trades from Westchester to New-York, once or Twice a Week, having for some time past been employ’d by severals, to buy and sell country produce, has it in his power to supply, and bring to New-York, for all such as shall employ him, (on a short notice, for shipping or home use, any sort of country produce, according to the season of the year, as sheep, hogs, all kinds of poultry, butter, cheese, gammons, apples, cyder, flaxseed, & c. he intending to follow the business: All persons who shall favour him with their commands, may depend on being served according to bargain made, with integrity and dispatch: He may be spoke with at Adolph Waldron’s, near the ferry stairs, or at Captain Giles’s, near the North-River, or on a line being left at either places, he will attend them where they shall direct for him to call upon them who please to employ him. Moses Watman. AuthorThank you to HRMM volunteer George Thompson, retired New York University reference librarian, for sharing these glimpses into early life in the Hudson Valley. And to the dedicated HRMM volunteers who transcribe these articles. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

"On the River" was a public television project of WTZA-TV, Hudson Valley Television, Kingston, New York. Running from 1986/87-1993, all episodes of this series are now held in the Marist College Archives as part of their Environmental History collection. This episode is shared with permission by the Hudson River Maritime Museum.

"Logbook 1" introduces the viewer to the Hudson River and the groups that were working to clean it up in 1987, including the Hudson River Sloop Clearwater, Riverkeeper, and more. We'll be sharing many of the river-related "Logbooks" from "On the River" over the next several Saturdays, so stay tuned!

Did you ever watch "On the River" when it originally aired? What was your favorite episode? Share in the comments!

If you'd like to see more videos from the Hudson River Maritime Museum, visit our YouTube Channel. For more "On the River" episodes, check out our YouTube playlist just for this show.

If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor’s note: Twenty years ago, four friends with an abiding love of the Hudson River and its history stepped away from their families and their work to travel up the river in a homemade strip-planked canoe to experience the river on its most intimate terms. The team set off from Liberty State Park in New Jersey and completed the adventure nine days later just below Albany where one of the paddlers lived. They began with no itinerary and no pre-arranged lodging or shore support. There were no cell phones. The journey deepened their appreciation for the river and its many moods, the people who live and work beside the river and the importance of friendship in sustaining our lives. Please join us vicariously on this excellent adventure. We'll be posting every Friday for the next several weeks, so stay tuned! Follow the adventure here. Making the DecisionTime to get back to the river. We gathered on my screened porch on a sultry evening to talk about our previous river adventures and soon we convinced ourselves to paddle the river once again. Instead of a major youth trip with all of the attendant planning, food, gear and boys of all ages and parents, we imagined a simpler, self-contained trip with one boat and no pre-planned overnight campsites. Of all of the available boats, we chose to use a 26-foot strip planked canoe named Bear. Built about 10 years earlier in a church basement, the Bear was large enough to take four or five adults and enough gear and food for a week. It had a simple mast and square sail for use when winds were favorable, that is running or sailing on a broad reach. The canoe had a relatively flat but slightly misshapen bottom, high freeboard, flat gunwales and an amber wood color inside and out. The deformation of the hull resulted from the collapse of the sides as the builders struggled to remove the boat from the dust laden church fellowship hall. Hydraulic jacks were required to once again give form to the canoe. Once thwarts were installed, she held her form for the most part. Remarkably, this canoe was an excellent rough water boat and a good sailor although her bottom would flex in an unsettling way over deep troughs. We decided to approach the journey differently this time. We chose to begin in Jersey City and use flood tides and expected southerly winds to carry us up the river. That way, when tired at the end of the journey, we would be home instead of trying to arrange to get the boat and gear home from some difficult site in metropolitan New York, most likely during a rush hour or some typical urban calamity. One month later on a humid and overcast fall day, we met at the old barn to get the Bear out of storage with help from the barn owner and several others. The canoe was in good shape after resting for three years. However, when we unfurled the canvas sail, two of us got facefuls of raccoon and mouse crap. After brushing it out, holes appeared. There was no time for sewing, so the sail was expertly mended with generous applications of duct tape. We inverted and hoisted the Bear onto the steel rack on Steve’s small rusted-out pick-up truck and fastened red rags to the awkwardly overhanging bow and stern. The weather forecast was unsettling. A cold front followed by northwest winds was expected to sweep through on day one, and three tropical storms are lined up in the Atlantic. We returned to our homes to pack our individual gear in bright yellow dry bags. Sunday (day of departure)We gathered on the river at Steve’s House in Cedar Hill for bagels and coffee before driving to Jersey City in the truck and Dan’s father’s car. We arrived at Liberty State Park in approximately two hours and after driving around the perimeter of the park we found the boat launch. It was sunny and humid. We carried the Bear into the slip and stepped the mast, lashing it securely to the forward thwart. We loaded the boat with dry bags containing personal gear, tents, food and water. By now, curious onlookers had gathered and we took a few moments to tell them we were headed for Albany. They shook their heads in disbelief. New York Harbor and Manhattan At 12:45, we said goodbye to our drivers, Roger and Dave, and began paddling directly toward Bedloe’s Island and the Statue of Liberty. A light west breeze could be felt, so we raised our newly mended sail and threaded a course between the Statue and Ellis Island. Did you know that the Statue of Liberty once served as an official lighthouse? We passed several ferries carrying tourists to the monuments before rounding Ellis Island and turning north into the mouth of the Hudson River. The wind began strengthening and shifting to the northwest setting up choppy waves as we sailed up the river. We were able to cant our sail and sail on a reach as the wind rose to 10-20 mph. Power cruisers began churning up big wakes and each time we had to turn the canoe to meet them head on, losing momentum. One wave soaked Dan in the bow and me in the stern, carrying away my water bottle. The leading edge of the spar carrying our square sail proved hazardous to Joe and Dan in the bow. Steve’s Giants hat blew off and smacked me in the chest. We lost a paddle and had to backtrack. A small keel sloop from a nearby sail training outfit joined us briefly and we were actually able to pull ahead of her. A very handsome French ketch sailed by on her way to the basin at 79th Street. We began to drift leeward toward the Manhattan waterfront and the twin towers of the World Trade Center. Wind and tide turned against us in the vicinity of West 30th Street and after struggling against them and making little progress, we pulled for the marina at Chelsea Piers at 3:30 for a much needed break. Here, we washed the salt spray off our faces, bailed out the bottom of the canoe and replenished our fresh water. At 4:00 PM we tried once again to make some progress. We tried to sail off of the northwest wind but without leeboards it was futile. We took down the sail and doggedly paddled north. We came upon up to a long rusty car float with spuds that was being used as a makeshift pier. The old lightship Frying Pan, recently raised from the bottom of Chesapeake Bay was tied up to it and at its outboard end was a rusty 1931 fireboat named John J. Harvey. There was a group of dirty but determined guys making repairs at the fantail (they later succeeded in making the fireboat operational; a year or so later, these same guys and their fireboat helped to evacuate lower Manhattan and pump water to the burning wreckage of the World Trade Center). We said hello and continued inching our way north. At 5:00 PM, exhausted and discouraged, we pulled out of the open river and into the lee of the aircraft carrier Intrepid, near 42nd Street, just to get out of the wind. It should have been slack tide but the current was still strong and southerly. We figured that we still had five miles to go to reach the George Washington Bridge and six more after that to reach a good campsite. This goal was becoming increasingly unlikely. Not to mention that we needed a rest. During our interlude below the Intrepid, we watched three cruise ships back into the river, turn with the assistance of tugs and head for sea. We drank lots of water and told a few stories, including a few of Steve’s Peace Corps tales. His description of the parasitic guinea worm and the way it eats its way through human flesh to release eggs did not improve morale. At 5:30 PM we covered our dry bags with the dirty canvas sail and decided to paddle for New Jersey in hopes of getting under the lee of the headlands leading to Fort Lee. It was fortuitous timing. Moments after departing on our westward heading, NYPD arrived in force at the Intrepid, apparently in search of a small boat load of refugees or terrorists. With blue lights flashing, they were everywhere; in squad cars on the pier, in patrol boats in the slip and individually climbing down beneath pilings. In fact the only place they failed to look was west toward the open river. We finally realized that the only place they couldn’t look was toward the setting sun and so we were able to escape by staying exactly between the setting sun and the Intrepid as we made our way to somewhere in New Jersey. We pulled into the Port Imperial Marina for a rest since the wind and tide remained adverse. After drinking lots of water and realizing that the flood tide was not going to arrive in time to help, we began paddling north again in search for a place to spend the night. The New Jersey shoreline here was bleak and industrial and our progress was excruciatingly slow. We began losing daylight. Ever the optimist, Steve tells us that “the Lord always provides” and that “He loves canoeists.” He suggested that we consider the 79th Street basin in Manhattan, but I expressed concern about security. As night descended, we discovered an abandoned and undeveloped railroad pier with brush and grass, roughly west of 79th Street. The shoreline was littered with junk and the outer end of the pier was separated from a construction site and high-rise residential towers by a big earthen berm. We landed, investigated the site and agreed with Steve that the Lord had indeed provided for us. Hence we named this place “Providence Pier.” We drew the Bear well above the wrack line and set up camp in a clearing. Joe began dinner. Dan and I climbed up the berm to see what was in the immediate vicinity and noted an auto lube shop and a nearby hospital. It did not seem likely that we would be seen or disturbed. Meanwhile, we enjoyed the spectacular lights of Manhattan. Dinner was served at 9:30 PM and consisted of an appetizer of cheese and tomatoes and a main course of macaroni, spaghetti sauce and hot dog chunks. A full moon came up and the wind rose to 30 mph. We had a magnificent view of the brightly lit Manhattan skyline. Steve chose to sleep under the stars but the rest of us climbed into pup tents. A family of skunks visited, but was content to sniff Steve and turn in for the night. The rising wind was an ominous sign for the next leg of the trip. Don't forget to join us again next Friday for Day 2 of the trip! AuthorMuddy Paddle’s love of the Hudson River goes back to childhood when he brought dead fish home, boarded foreign freighters to learn how they operated and wandered along the river shore in search of the river’s history. He has traveled the river often, aboard tugboats, sailing vessels large and small and canoes. The account of this trip was kept in a small illustrated journal kept dry within a sealed plastic bag. The illustrations accompanying this account were prepared by the author. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

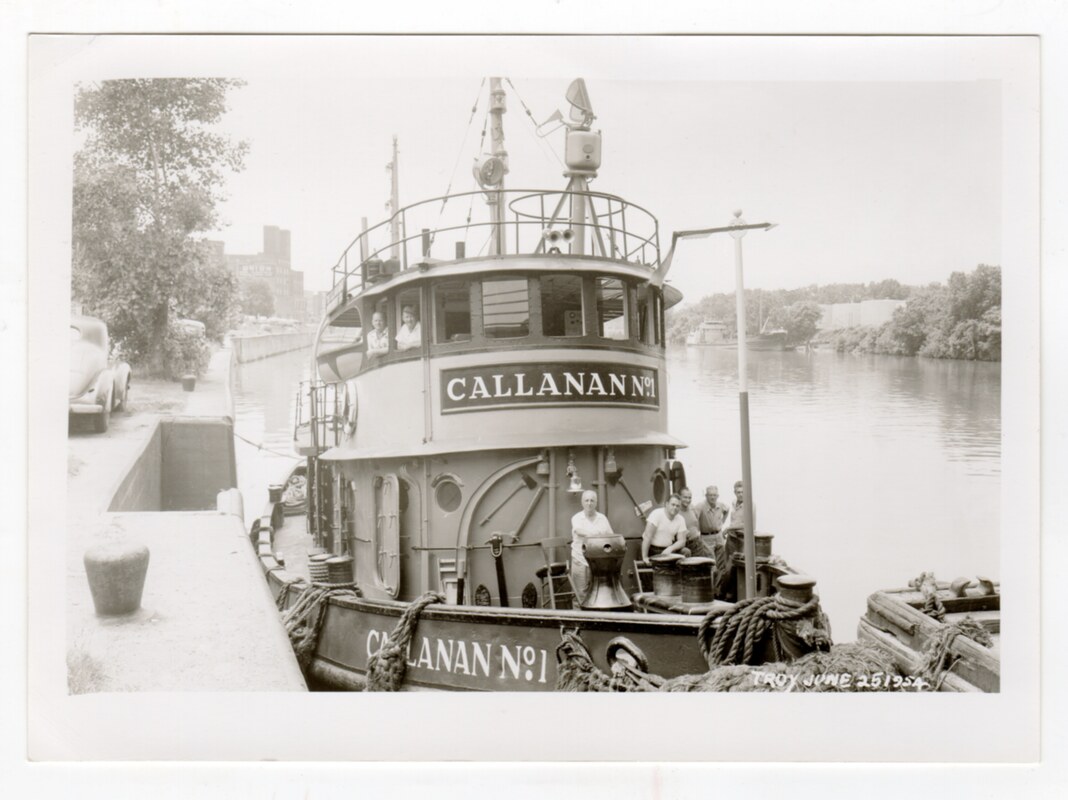

Editor’s Note: The following text is a verbatim transcription of an article featuring stories by Captain William O. Benson (1911-1986). Beginning in 1971, Benson, a retired tugboat captain, reminisced about his 40 years on the Hudson River in a regular column for the Kingston (NY) Freeman’s Sunday Tempo magazine. Captain Benson's articles were compiled and transcribed by HRMM volunteer Carl Mayer. See more of Captain Benson’s articles here. This article was originally published October 31, 1971. A Riverman’s Log’ New Tempo Feature TEMPO begins Sunday publication with several new features. And, proud as we are of all of them, the one that promises to become our own personal favorite is a regular column by Captain William O. Benson. You’ll find the first offering by Capt. Benson taking up a full page spread in this week's issue, complete with nostalgic photos of the tugboat Lion and the steamboat M. Martin, and appearing under the banner headline “Whistles Salute Two Presidents.” Captain William Odell Benson is a life-long resident of Sleightsburgh, where he was born on March 17, 1911, the son of the late Albert and Ida Olson Benson. As captain of the tugboat Peter Callanan, he retains memories of incidents and anecdotes along the Hudson River; has long known the waterway’s steamboats and the men who manned them. The perfect choice then to author about steamboating on the Hudson in years past. 40 Years on River Bill Benson's reminiscences on Hudson River life and lore now join this magazine as a regular feature; will be culled from his 40 years of working, will appear weekly for a long time to come. A river boatman his entire working life, he was closely associated with the Hudson and its steamboats long before he took to the tides himself. His father was ship's carpenter of the famous in-legend Mary Powell; held the same position for the Central Hudson Steamboat Company and the Cornell Steamboat Company. His older brother, Algot J. Benson, before his death in 1923, served as chief mate and pilot of the steamboat Onteora, had been a deckhand and quartermaster on the Mary Powell, and a quartermaster of the Long Island Sound steamers Plymouth, Concord and Naugatuck. TEMPO’s new contributor can lay claim, as well, to having been named after a Hudson River steamboat. His middle name, “Odell,” derives from the steamboat Benjamin B. Odell, the largest steamer of the old Central Hudson Line, which entered service on the river the year Capt. Benson was born. The wealth of anecdotes at your columnist’s recall date back to his school days at the old District No. 13 School, Port Ewen. Education completed, he left school in 1927 to work for the Hudson River Day Line at Kingston Point. The years of 1928 and 1929 saw him serving as a deckhand on the old Day Line steamer Albany. Then came a long period (1930 to 1946) as a deckhand, pilot and captain on the tugboats of the Cornell Steamboat Company. Served on Many Tugs Those Depression to post-World War II years saw him serving on the Cornell tugs S. L. Crosby, Lion, Jumbo, Bear, Pocahontas, Perseverance, George W. Washburn, R. G. Townsend, Edwin Terry, J. G. Rose, Cornell, Cornell No. 20, Cornell No. 21, Cornell No. 41, John D. Schoonmaker, Rob, and William S. Earl. During 1946 he captained the tugboat maintained at Poughkeepsie to assist tows to pass safely through that city’s bridges. Since 1947 he’s been pilot and captain on the Callanan Road Improvement Company's tugboats Callanan No. 1 and Peter Callanan, and other tugs that from time to time have been chartered by the Callanan Company. The steamboat columns we've received in advance read like a riverman’s log of humor and heritage. Suffice it to say that we're looking forward to each new Benson column with as much enthusiasm as any other TEMPO reader. We welcome the captain aboard with a salute of three whistles; look forward to pleasurable hours of reading about the men and the boats of the Hudson's past in the months ahead.  Tug "Callanan No. 1" a Kingston, N.Y. tug at Troy, N.Y., June 25, 1954, 12:30 p.m. Left to right in Pilot House: W.O. Benson (Sleightsburgh, NY); Peter Tucker, (Kingston, NY); Ed Carpenter, cook (Ulster Park, NY); Bud Atkins, deckhand (Port Ewen, NY); Chris Mancuso, deckhand (Greenpoint, NY); Jim Malene, 1st Assistant Engineer (Kingston, NY);Teddy/Theodore Crowl, 2nd Assistant Engineer, (Farmingdale, NY). AuthorCaptain William Odell Benson was a life-long resident of Sleightsburgh, N.Y., where he was born on March 17, 1911, the son of the late Albert and Ida Olson Benson. He served as captain of Callanan Company tugs including Peter Callanan, and Callanan No. 1 and was an early member of the Hudson River Maritime Museum. He retained, and shared, lifelong memories of incidents and anecdotes along the Hudson River. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Although you may never have heard of him, Buster the brindle bulldog was once one of the most famous dogs on the Hudson River. The pet of Capt. and Mrs. A. Eltinge Anderson, Buster accompanied his master at his work aboard the steamboat Mary Powell. Much beloved by both passengers and crew, Buster was so good at a number of tricks, he ended up in the newspaper On August 23, 1903, the New York Times, published a biographical account of Buster and his exploits. The Kingston Daily Freeman, eager to pay tribute to the local hero, published the same account a few days later on August 25th: Of all the mascots which are supposed to bring good luck to the ships and boats which ply in the harbor of New York there is none more accomplished than “Buster,” the mascot of the Mary Powell, the Albany Day Line boat which runs between New York and Kingston on the Hudson. “Buster” is a dog owned by Capt. Anderson and is held in affectionate regard not only by all the members of the crew of the Mary Powell, but by all of the residents of Hudson River towns who are frequent passengers on that steamer. “Buster” is six years of age, having first seen the light of day on March 4, 1897, the date of President McKinley’s first inauguration. His tutors have been Capt. Anderson and the members of the Mary Powell’s crew, and he has progressed so well under their instruction that Capt. Anderson now declares him to be the best swimmer and sailor connected with the boat. “Buster” takes to water like a duck. An invitation from his master to disport himself in the Hudson River fills him with delight. With one leap he is over the railing of the boat and he can frolic around in the water for an hour without getting tired. As it is impossible for him to make a landing once he is in the water owing to the docks and the sea wall around the Albany Day Line’s wharf, he is brought back into the boat by a peculiar and ludicrous manner. Capt. Anderson sends one of the members of the crew out onto a float and the sailor lures “Buster” to the float by throwing him a stick. “Buster” goes after the stick and brings it back to the float in his mouth. The sailor then catches hold of the stick and hauls “Buster” up onto the float, the dog retaining a firm grip on the piece of wood. Once “Buster” is on the float, another sailor throws out a line to the man on the float. This is fastened around “Buster’s” body. The dog is then told to take another dive. When is he again in the water, the sailor on the boat pulls him in just as he would a fish. This Summer, when the Mary Powell was being painted, one of the painters fell from the scaffolding, on which he was standing, into the river. “Buster” was a witness of the accident. Quick as a flash he leaped into the water after the painter and grabbed him by the collar to help him. Fortunately the painter was a good swimmer and did not need the dog’s assistance. As soon as “Buster” realized that his services were unnecessary, he let go his hold on the man and swam after the painter’s hat, which was being carried off by the tide. Securing this, he put back and reached a float some distance from the Mary Powell just as the painter was making a landing. “Buster” is cleverer at catching a line than any member of the crew. He rarely ever misses. If the line is thrown a little short, he makes a leap for it. There is no dog performing before the public who can do more clever and interesting feats than “Buster.” For the delectation of the passengers Capt. Anderson sometimes has the sailors of the boat form a line and make a loop of their arms. “Buster” leaps through these loops one by one without a break. “Buster’s” religious education has not been neglected. He has been taught to pray, and it is a most amusing sight to see him in this act. At a word from his master he leaps into a chair, places his forepaws over the back of the chair and bows his head reverentially. He maintains this attitude until Capt. Anderson says “Amen.” He has many other tricks equally interesting. On Thursday, March 12, 1908, at the ripe old age of 11, Buster passed away. On that date, the Kingston Daily Freeman reported "BUSTER IS DEAD. Mrs. A. E. Anderson's dog, Buster, the best known dog along the Hudson, died this morning of old age."

The following day, on Friday, March 13, 1908, they reprinted the above biography, but with an addendum on the end: Since the above was first published "Buster" had added to his accomplishments. He was the owner of a pass on the local trolley line, and often used the privilege when alone, boarding and leaving the cars the same as any other passenger. Perhaps Buster took a trolley like the one above! The staff and volunteers of the Hudson River Maritime Museum had a delightful time researching Buster and his history. We hope you enjoyed this story as much as we did. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today! Editor's Note: The following text is a verbatim transcription of an article written by George W. Murdock, for the Kingston (NY) Daily Freeman newspaper in the 1930s. Murdock, a veteran marine engineer, wrote a regular column. Articles transcribed by HRMM volunteer Adam Kaplan. For more of Murdock's articles, see the "Steamboat Biographies" category. No. 32- Escort The “Escort” was built at Mystic Bridge, Conn., in 1863, and was 185 feet long, carrying a gross tonnage of 675 and a net tonnage of 500. She was propelled by a vertical beam engine. Built for service in the east, the “Escort” sailed the waters of the Connecticut river and Long Island Sound and was then chartered to the government in the Quartermaster’s Department during the Civil War. At the close of the war she was brought north again and used in eastern waters until 1873. The “Escort” was then purchased by Catskill people and put in service on the Catskill and New York night line. In 1883 the “Escort” was rebuilt and her name was changed to the “Catskill”. She ran in line with the “Kaaterskill” and “Walter Brett”. On September 22, 1897, the “Catskill was rammed and sunk off West 57th street, New York, about seven o’clock in the evening by the steamer “St. Johns”, owned by the Central Railroad of New Jersey. There were 46 passengers aboard the “Catskill” and all escaped except a five-year-old boy, Bertie Timmerman of Leeds, who was drowned. At the time of the accident, the “Catskill” had an unusually heavy cargo of freight aboard for her north-bound trip. The usual signal whistles were blown but there was evidently a misunderstanding and the two vessels came together with a crash that could be heard for some distance along the waterfront. The excursion steamboat struck the “Catskill” on the starboard side about 30 feet aft of the bow and tore a great hole in her side, the whole depth of her guards and freeboard and way below the waterline. Captain Braisted of the “St. Johns”, seeing that the damage to the “Catskill” was serious and that the vessel would sink, blew his whistle for aid and a passing steamer and some tugs rushed to the assistance of the “Catskill” and took off the passengers. The “Catskill” was raised and rebuilt, being lengthened from 185 to 226 feet two inches, and her tonnage was increased from 675 gross tons to 816 gross tons. Her name was then changed to the “City of Hudson”, and when she made her appearance she gave the impression of an entirely new vessel. The “City of Hudson” continued running on the Catskill line until the fall of 1910, when she was laid up at Newburgh, having outlived her usefulness. She was purchased by Charles E. Bishop of Rondout and Abram W. Powell of Port Ewen in October, 1911, and taken to Port Ewen, where she was dismantled, her engine and boiler being junked and her woodwork used for fuel in burning brick on a brickyard. AuthorGeorge W. Murdock, (b. 1853-d. 1940) was a veteran marine engineer who served on the steamboats "Utica", "Sunnyside", "City of Troy", and "Mary Powell". He also helped dismantle engines in scrapped steamboats in the winter months and later in his career worked as an engineer at the brickyards in Port Ewen. In 1883 he moved to Brooklyn, NY and operated several private yachts. He ended his career working in power houses in the outer boroughs of New York City. His mother Catherine Murdock was the keeper of the Rondout Lighthouse for 50 years. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

On September 22, 1897, Mrs. Edith Gifford boarded a yacht on the Hudson River along with other members of the New Jersey State Federation of Women’s Clubs (NJSFWC) and male allies from the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society (ASHPS). The goal of this riverine excursion was to assess the horrible defacement of the Palisades cliffs by quarrymen, who blasted this ancient geological structure for the needs of commerce—specifically, trap rock used to build New York City streets, piers, and the foundations of new skyscrapers. All on board felt that seeing the destruction firsthand, with their own eyes, was the first step in galvanizing support for a campaign to stop the blasting of the cliffs. The campaign that followed was successful: Women from the NJSFWC lobbied Governor Foster Voorhees, while men from the ASHPS found support in their own Governor Theodore Roosevelt. Their efforts led to the creation of the Palisades Interstate Park Commission (PIPC) in 1900 through an act to "preserve the scenery of the Palisades." Under President George Perkins, the Commission purchased or received successive tracks of land to save the Palisades from quarry operators, resulting in iconic recreational areas such as Bear Mountain State Park. When the Palisades Interstate Park opened in 1909, few could imagine that it would become one of the most popular public parks in the entire nation. A landscape marked by resource extraction became a landscape of recreation, environmental education, and nature appreciation. The yacht trip characterized the collaborative nature of this critically important conservation story. What brought these groups and others together was not only a shared interest in the value of scenic beauty and recreation, but also a desire to save the trees growing along the base and top of the cliffs—an issue tied to other environmental initiatives at the time, especially the creation of a public park in the Adirondacks to protect the sources of the Hudson River. Women from the NJSFWC, especially Mrs. Edith Gifford, joined leading forestry experts like Gifford Pinchot and Bernhard Fernow in calling for the protection of the Palisades woodlands and other forested areas across New Jersey. Unlike scientific foresters, however, Mrs. Gifford and other women focused on public pedagogy. Through their efforts, the NJSFWC prepared the way for civic education, nature study, and environmental stewardship in Palisades Interstate Park and beyond. Seeing the Forest from the Rocks In the mid-1890s, as people on both sides of the Hudson began advocating for the preservation of the Palisades cliffs, many scientists and politicians were also beginning to recognize the importance of forests to water supplies. The publication of George Perkins Marsh's bestselling book Man and Nature in 1864 generated public discussion of the potentially disastrous consequences of large-scale deforestation: When trees are destroyed, Marsh warned, the ground loses its ability to hold moisture, and the disturbed ground becomes more susceptible to erosion. Deforestation threatened entire watersheds, impacting commerce, navigation, and public water supplies. His conclusions influenced emerging forestry experts, businessmen, and politicians, ultimately leading to the creation of a Forest Preserve in 1885, Adirondack Park in 1892, and the addition of the “Forever Wild” clause to New York State’s constitution in 1894. Just as in the Adirondacks, scientific foresters in New Jersey raised concerns about the impact of deforestation on the state’s water supplies. As urban and suburban populations across New Jersey swelled, many felt that preserving water supplies and spaces for recreation was more valuable, and more feasible, than reviving timber revenues. In 1894, the NJ State Legislature ordered that a survey of the state’s forests be included in the State Geological Survey. The survey’s purpose was to determine the possibility of creating a network of forest reserves across the state to satisfy needs for water and recreation. It highlighted how the forests of the Palisades were composed of high quality, old-growth trees, vital to the protection of water supplies in the Hackensack Valley below. The survey also noted the Palisades’ value for future students of forestry. “This beautiful forest,” the report stated, “has almost as good a claim to future preservation as the escarpment of the Palisades.” The State Forester of New Jersey at the time was Dr. John Gifford, husband of NJSFWC member Mrs. Edith Gifford. Both had been active members of the American Forestry Association and shared a passion for trees. Dr. Gifford was the founding editor of New Jersey Forester, which ultimately became American Forestry, the journal of the U.S. Forest Service. Mrs. Gifford was active in numerous urban reform and environmental campaigns. After the establishment of the NJSFWC in 1894, she worked to bring the issue of forestry into the discourse surrounding the preservation of the Palisades from quarrying. A newspaper report described her this way: “Mrs. Gifford is a New Jersey woman who makes a special study of forestry for the NJSFWC when not engaged in household duties. She can tell you all about the management of European forests…[and] pathetic tales of wanton destruction of beautiful forests in this country.” In 1896, she was appointed Chair of a new Committee on Forestry and Protection of the Palisades at the NJSFWC. While scientific foresters focused on reports and surveys, Mrs. Gifford devoted herself to educating the public. At a NJSFWC meeting in 1896, which was attended by numerous state legislators and some of the nation's leading foresters, she showcased a traveling forestry library and exhibition, intended to educate the public, and especially children, about the importance of forests and forestry. The exhibition included contrasting images of ‘pristine’ forests and those ravaged by lumber dealers for economic profit; depictions of trees in art and leaf charts by Graceanna Lewis; maps of New Jersey forests and their connection to the state's geology; portraits of notable trees; and examples of erosion caused by deforestation in France and other European countries. The library consisted of a bookcase made of oak, encased in “a traveling dress of white duck.” Other women’s groups, libraries, and schools across the state could apply for the privilege of hosting it for a month. It included major forestry textbooks of the day, including What is Forestry? by Bernhard Fernow; Franklin Hough’s Elements of Forestry; tree planting manuals; and pamphlets on forestry’s importance to watershed protection and timber supplies. Sargent attended the meeting and wrote a rave review in his journal, Garden and Forest. Applauding the role of women in increasing public literacy about trees, forests, and forestry, he linked their efforts directly to policy making. "No comprehensive forest policy," he wrote, "can even be devised without a more cultivated public sentiment." The exhibition and traveling forestry library were not merely didactic tools, Sargent explained; they encouraged a sentimental connection between trees and people. The "cultivation of a sympathetic love of trees," for Sargent, was the basis for citizen involvement in forestry, forest preservation, and nature appreciation. “The arrangement of this exhibit," Sargent remarked, "was so effective that it seemed a pity that it must be transient, and the suggestion that every library and schoolroom should have something of this kind…was felt by all who saw it.” In the wake of this meeting, Mrs. Gifford’s traveling forestry library circulated in women’s clubs across the state. Clubs applied for the privilege of hosting the oak bookcase for a month at their own expense and used it to generate public discussion of forestry issues. Explaining the necessity of such a library as well as other forms of outreach—including reading circles and exhibitions—Gifford stressed the centrality of pedagogy to policy making: “Much education is needed to bring about necessary legislation and progressive methods,” she argued. Going further, Mrs. Gifford took the cause of public education and forestry to the national level. At a General Federation of Women’s Clubs meeting in 1896, of which the New Jersey State Federation was a part, she urged members across the country to take a pledge to forestry by declaring among themselves, “We pledge ourselves to take up the study of forest conditions and resources, and to further the highest interests of our several States in these respects.” Copies of the document were sent out to all 1500 local GFWC clubs as well as the press, augmenting both women’s role in forest protection and public awareness of the problem. The pledge in its entirety was published in her husband's journal, The Forester, shortly afterwards, ensuring widespread media attention. Mrs. Gifford was not the NJSFWC’s lone forestry advocate. Mrs. Katherine Sauzade, for instance, included the value of the Palisades woodlands in her 1897 speech calling for the preservation of the Palisades. Whereas Mrs. Gifford stressed the importance of healthy forests to healthy waterways, Mrs. Sauzade instead emphasized the role of trees in creating the “wild, rugged character” of their beloved Palisades. In this instance, trees functioned as part of the scenic beauty of the area; their value was not as parts of an invisible system, but as part of the visual splendor of the place. For Sauzade, destroying the scenic beauty of the trees as well as the cliffs was an attack on civilization itself. “We cannot escape,” she wrote, “the disgrace, nor the just censure of the civilized world if we permit, by further neglect, the continued defacement of these grand cliffs.” By the time the yacht set sail on the Hudson in September 1897, therefore, forestry was already a dominant interest at the NJSFWC and elsewhere in the state. On deck, watching the blasting of the cliffs of the Palisades at the Carpenter Brother’s quarry, Mrs. Gifford declared that “the forestry interest…exceeds the interest of preserving the bluffs.” Reminding her colleagues of her studies of the Palisades woodlands, she remarked that “in some places, the Palisades look exactly as they did when Hendrick Hudson sailed up the river. That is a very remarkable thing to find a primeval forest near the heart of a great metropolis.” Mrs. Gifford’s statement was supported by Joseph Lamb of the ASHPS, who built one of the first resorts on the Palisades in the 1850s. “The Palisades,” he stated on the yacht, “are perhaps more valuable as woodlands than anything else.” At a national GFWC meeting in 1898, NJSFWC President Cecelia Gaines (later Cecilia Gaines Holland), raised the issue of forestry and the protection of the Palisades once again: “There are utilitarian reasons for the protection of the Palisades,” she told club members. “The valleys at their feet are covered with farms and small towns whose water supplies are drawn from sources in the Palisades. Disturb or remove these sources by blasting and the dwellers below suffer in consequence.” From Nature Study to Nature Appreciation Despite the essential role of the NJSFWC in the creation of the Palisades Interstate Park Commission in 1900, women were excluded from the commission itself on the basis of their gender. This, however, did not stop their involvement in Palisades conservation or in forestry more generally. In 1905, GFWC President Lydia Phillips Williams declared in a speech at the American Forestry Congress that “[The GFWC’s] interest in forestry is perhaps as great as that in any department of its work…[forestry committees] are enthusiastically spreading the propaganda for forest reserves and the necessity of irrigation.” By 1912, however, women were excluded once again, this time from the American Forestry Association—the organization that Mrs. Gifford had once been a part. Environmental historian Carolyn Merchant suggests that this shift was due to the full-fledged institutionalization of scientific forestry, which was not accessible to women, or to their opposition to Hetch Hetchy. With the creation of the PIPC in 1900, interest in protecting the forests of the Palisades for water supplies continued. At the opening ceremony for Palisades Interstate Park in 1909, New York Governor Charles Evans Hughes stated that he hoped that the creation of the park was the first step in “[safeguarding] the Highlands and waters…The entire watershed which lies to the north should be conserved.” George Frederick Kunz, a curator at the American Museum of Natural History, echoed this sentiment in his own address. Pointing to the example of the Adirondacks, he said, “It must be borne in mind that without your forests you would have no lakes…until we have reforested our hills, we will not have proper water for this river.” Reforesting the Palisades through tree planting was part of the growth of the park itself. Students at newly created professional forestry programs at Yale and the New York State College of Forestry in Syracuse contributed to this process—in 1916 alone, students planted 700,000 trees. In the 1930s, the Civilian Conservation Corps managed wooded areas in Palisades Interstate Park, planted trees, and constructed new infrastructure. Forestry students also used the woodlands of the Palisades as a laboratory, studying the area’s vegetation, conducting ecological surveys, and developing forest management plans. Yet, as Palisades Interstate Park grew, the social and recreational aspects of forestry were stressed more than its importance for water or timber supplies. Given their close proximity to New York City, the value of the Palisades’ woodlands to public welfare and urban reform—key tenets of the Progressive Era—could not be ignored. In 1920, the New York State College of Forestry at Syracuse published a bulletin that outlined the value of “recreational forestry” in the Palisades. “The Palisades Interstate Park of New York and New Jersey,” it stated, “on account of its proximity to the American metropolis, is, and should be, dominated by the needs of the people in the vicinity of this great city.” In a section called “Forests versus City Streets,” the author addressed how forestry camps could improve the well-being of New York City’s low-income residents. “Outdoor influences,” he wrote, “…curb and counteract tendencies of other environments which fail to promote the ultimate good of these juvenile elements of society.” He continued, “Impossible it is to estimate the aggregate of all the impressions of associations that stir the dull soul…and influences that prompt to effort and incite nobler living.” Similarly, an ecological survey of Palisades Interstate Park in 1919 included an entire section on “The Relation of Forests and Forestry to Human Welfare.” While the survey began by discussing social forestry initiatives in Palisades Interstate Park, it concluded by addressing the public needs that inspired National Parks: “The moment that recreation…is recognized as a legitimate Forest utility the way is opened for a more intelligent administration of the National Forests. Recreation then takes its proper place along with all other utilities.” Far from city streets, park visitors experienced the wonder of the Palisades woodlands firsthand through excursions and nature study. When they left, they brought back a new appreciation for nature of all kinds. Mrs. Gifford’s pedagogical mission, therefore, was ultimately realized in the park itself. Few could have predicted in the 1890s how much of an impact the introduction of trees to a campaign to save an ancient geological structure would have. Recognition of the importance of an informed public shaped not only the growth of the park itself, but also the future of environmentalism in the United States. AuthorJeanne Haffner, Ph.D., is a landscape historian and associate curator of “Hudson Rising” (March 1 - August 4, 2019) at the New-York Historical Society. She previously taught environmental history and urban planning history and theory at Harvard and Brown Universities, and was a postdoctoral fellow in Urban Landscape Studies at Dumbarton Oaks (Harvard). This article was originally published in the 2019 issue of the Pilot Log. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

In working in the archives today with volunteer G.M. Mastropaolo, we discovered this delightful timetable in the Donald C. Ringwald collection. Outlining travel times and locations for steamboats, steam yachts, ferries, stages/stagecoaches, and railroads in Rondout, Kingston, "and vicinity." Among the many time tables is that of the ferry boat Transport. To learn more about the Transport, check out our past blog post about its history and use. Of particular interest to the collections staff and volunteers at the museum was this time table for the steamboat Mary Powell, the star of our 2020 exhibit, "Mary Powell: Queen of the Hudson," opening April 25, 2020. "Handy Book of the Catskill Mountains" was designed for those traveling to the Kingston area for access to the Catskill Mountains and mountain houses. Measuring just 4 by 2.5 inches, this tiny little handbook would fit perfectly in a pocket or lady's reticule. The Hudson River Maritime Museum is pleased to make this handbook available to the public. If you would like to view the entire book, chock full of both traveler's information and period advertisements, click the button below to download a PDF. If you enjoyed this blog post and would like to support the work of the Hudson River Maritime Museum, please make a donation or become a member today!

March, 2020 is March Membership Madness here at the museum. If you join in the month of March, you can receive 20% off (for 2020) any membership level. Learn more. |

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 [email protected] Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |