History Blog

|

|

|

|

|

Editor's Note: The following is a verbatim transcription of a chapter from Spalding's Winter Sports by James A. Cruikshank, published in 1917 and part of the Ray Ruge Collection at the Hudson River Maritime Museum. Many thanks to volunteer Adam Kaplan for transcribing this booklet. This is our final installment - thank you for reading along! Perhaps in no outing of the year will the confidence and assurance of the beginner bring such unfortunate punishment as in the winter cruises over the snow and in the cold. Neglect of the simple precautions which the expert has learned to regard as absolutely necessary may bring trouble, not merely to the individual, but to the entire party. It is no small trial to find that, because some over-confident amateur has rushed off on the trip with insufficient preparation or equipment, the entire plans of the party must be changed, or perchance the individual will become the ward of the group. A severe frost-bite, a shoe too tight, an ill fitting binding of snowshoe or ski, a broken snow implement- these are generally things which can be avoided with a little anticipation and forethought. It is no joke to attempt to guide or carry home some husky amateur who has paid the penalty of foolhardiness by starting out ill-equipped; nor is it pleasant to be left alone by a sputtering fire in the heart of the snow laden woods while somebody strains to get help. One such experience will cure anybody, and it will also break up a pleasant outing and some of its friendships. The best plan on all winter outings which take the party any considerable distance from headquarters is to select and appoint a captain known to be familiar with the work in hand. His opinion should be final. He should even have the authority to refuse a place in the party to those who are not properly equipped. This is the custom among many of the oldest and strongest winter organizations of the country, whose winter outings increase in popularity and interest every year. It is important to keep tally of the number of persons in the party and to “count noses” occasionally, especially where the going is bad and when teams are taken for the return trip or for distant points. In laying out trails, care should be taken to leave marks indicating any possible deviation in the route, either by arrows drawn in the snow, paper stuck in a split stick and stood up in the trail, snow mounds, or broken branches laid across the trail not to be followed. In snowshoe work the leader should adapt his stride to the shortest member of the party. In hill climbing he should make short steps, and the following members of the party should place their snowshoes accurately in the first track so that the steps do not become ragged and useless. Among the valuable items of the equipment, for either individuals or parties, are maps of the country, a compass, drinking cups, matches, knife, extra length of rawhide for possible repairs, safety pins, length of strong rope wound around some member as a belt. A folding candle lantern will often be very useful. It is not always agreeable to make an extended stop for lunch, and many of the most enthusiastic winter cruisers carry only such lunch as can be conveniently eaten while en route. Shelled nuts, raisins, sweet chocolate, triscuit, malted milk tablets, and crackers, are some of the best quick rations. Snow should not be eaten. If thirsty, a few raisins, lime tablets or even a bit of lemon eaten with a little snow may be used. Frost bite is the special thing to guard against in most amateur winter outings. It occurs with so little warning that the best plan is for each member of the party to watch the faces and ears of others in the party and give warning. The presence of a white spot should immediately be called attention to, and remedies applied. The first aid in this case is brisk rubbing with a woolen mitten, or glove, on which fresh snow is placed. In the case of frozen parts keep in the cold air and apply only cold treatment such as snow and very cold water until color and sensation return, when warm applications may be gradually used. Vaseline or any other greases should be applied after the frozen part has been brought to normal appearance. The continued use of snowshoes when the snow is very deep and heavy may bring on Mal de Raquette, most dreaded of all the winter troubles of the far north. It is caused by unusual and severe strain upon the muscles of the lower leg. The veins become clotted by overheating and the blood is kept in the lower extremities. Sometimes the limbs swell to two or three times the normal size and turn black. The premonitory symptoms of this very serious trouble are numbness of the limbs, lassitude and exhaustion. The remedy is to bare the legs to the skin, jump in the snow and stay there until the pain is unbearable, then rub the legs upward, toward the heart, until the flow of blood sets in. When symptoms are slight, the men of the north content themselves with elevating their feet and legs above the level of their heads as they lie and smoke, in which position the blood flows back into the body. Snow-blindness is frequent among the habitual outdoor folks of the north and should be guarded against by amateurs. There is no glare in all the year so severe as the glare of the sun from ice and snow. In Switzerland, in midsummer, the glacier travelers apply burnt cork to their faces, not merely to avoid sunburn but also to save the eyes. Automobile goggles are an excellent addition to the winter equipment, or smoked glasses, which should be fastened with a cord to the person. In case neither of these things are at hand, and the glare of the sun seems likely to cause trouble to any member of the party, a very simple prevention consists of a bit of flat wood, roughly whittled into the shape of goggles, and in the middle of which a narrow slit is cut. These are the Indians’ snow-goggles. No winter outing is complete without a photographic record of its interesting episodes. From the snowshoe tumble, which is so excruciatingly funny- to the other folks- to the tracks of wild creatures in the snow, there ranges every form of pictorial possibility. The equipment, however, should be light, simple and carried in waterproof and snow proof case. A box Kodak of set focus is always ready, and has many advantages. The postal size folding camera crowds it close in winter value and has scenic uses the cheap instrument lacks. One should remember that at no time of the year is there so much white light as in a mid-winter noon, and that the early day and the late day have deceivingly small amount of white light. AuthorJames A. Cruikshank was an expert on outdoors sports during the first half of the 20th century. Born in Scotland but spending most of his life in New York, he was the editor of The American Angler magazine, Field and Stream, and wrote numerous articles for a wide variety of other magazines and newspapers throughout his career, including the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. He also published at least three books: Spalding’s Winter Sports (1913, 1917), Canoeing and Camping (1915), and Figure Skating for Women (1921, 1922). He also contributed a chapter on artificial lures to The Basses: Freshwater and Marine (1905). In addition to his writing, Cruikshank was involved in public speaking, doing talks on outdoor sports sometimes illustrated by motion pictures. An avid photographer, Cruikshank’s photos often featured in his illustrated lectures, his articles, and his books, as he encouraged readers to take their own cameras out-of-doors. He had a home in the Catskills as well as a home and offices in New York City, and in the 1930s he helped found the Hudson River Yachting Association. At one point, he managed the Rockefeller Center ice skating rink, and another in Rye, NY. His wife Alice was also an avid camper and hiker, and they often traveled together. In 1909, Alice went “viral” in newspapers around the country by being the first person to blaze a trail between Mount Field and Mount Wiley in the White Mountains of New Hampshire (James brought up the rear). James and Alice eventually moved to Drexel, PA and were vacationing in Lake Placid in July of 1957 when James died unexpectedly at the age of 88. James Cruikshank went on to publish another book, Figure Skating for Women, in 1921, and remained a steadfast supporter of women in sports and outdoor photography.

If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

0 Comments

Editor's Note: Editor's Note: The following is a verbatim transcription of a chapter from Spalding's Winter Sports by James A. Cruikshank, published in 1917 and part of the Ray Ruge Collection at the Hudson River Maritime Museum. Many thanks to volunteer Adam Kaplan for transcribing this booklet. There is no reason why the average country club of the northern part of the United States or Canada should close up shop and hibernate during the winter. Some few pioneering clubs have already demonstrated that there is as much interest in sports of the winter as in those of the summer, and they are keeping open house all the year round. Some of the methods which are employed to interest the membership and provide what that membership desires in the way winter pastimes may be of value to other organizations. A toboggan slide will interest a very large proportion of the membership and can generally be managed on such a basis as to pay for itself, or at least for its maintenance. This has been the experience of the famous Ardsley Country Club, Ardsley, N.Y., which even went to the extreme of bringing to its club a recognized tobogganing expert of Canada, who directed the construction of its slide, and manages the rental of the toboggans and the maintenance of the slide. Almost any hilly country is adapted to the erection of a toboggan slide, and with a slight artificial stand with which to create initial impetus, a fine slide can be arranged. In small towns and sparsely settled communities it is often possible to arrange with the authorities for the use of one of the roads for certain hours or certain days, and with the placing of watchers at cross roads some of the magnificent sport which Switzerland enjoys in the way of coasting ought to be possible. The Lake Placid Club in the Adirondacks starts its toboggan slide from the roof of the golf house, which offers a suggestion other clubs may care to follow. Wooden troughs can be erected to carry the slide across brooks or gulleys, then the natural resources of the ground and the snow utilized again. The famous Swiss runs are first banked with snow and then water, which is piped all along the run, is sprayed upon the snow banks. There is tremendous side thrust to a heavily loaded toboggan or bob-sled going at great speed around a curve, and the construction of the slide should be strong and safe. The construction of an ice rink is easy where there is either a small brook nearby or water piped to the vicinity. Tennis courts are often used as the foundation of ice rinks, and serve admirably, but the water must be drawn off at the first approach of spring or the field will remain soft for an uncomfortably long time. The better plan is to have a special field for the ice rink, lay clay foundation and make side walls of 8 or 10 inches in height. When the first cold weather comes spray the field with a fine rose spray flung high in the air so that it freezes immediately upon touching the ground. Do not flood any skating field unless you want shell ice, at least not in the vicinity of New York or any place of similar average temperature. Of course, where there is a running brook, the building of a low dam, often merely 2 or 3 feet in height, will serve to back the water up over lowlands and provide a very satisfactory skating field during steady cold weather. A flood-gate should be put in the dam, however, so as to raise the level at any time, and thus create a new skating surface and get rid of the snow. It is most important that when snow has fallen on a skating field it must not be walked over, since the hardened footprints will remain and form annoying lumps, even after the balance of the snow has melted. It is much better to remove all snow as it falls, however, unless the size of the field is too large. Skating on ice which has been formed by spraying onto clay bottom may begin when 1 inch of ice has been formed. Where ice forms over water, the following thicknesses are necessary for various weights; 2 inches will sustain a man or properly spaced infantry; 4 inches will sustain a horse; 6 inches will sustain crowds in motion; 8 inches will sustain men, carriages, and horses; 15 inches will sustain passenger trains. Ice which is disintegrated by the action of salt water loses nearly 50 per cent. of its sustaining strength. It is now generally calculated that the large free skating coming into popularity in this country, and known as the International style, requires a rink of about 25 by 50 feet for a dozen persons. AuthorJames A. Cruikshank was an expert on outdoors sports during the first half of the 20th century. Born in Scotland but spending most of his life in New York, he was the editor of The American Angler magazine, Field and Stream, and wrote numerous articles for a wide variety of other magazines and newspapers throughout his career, including the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. He also published at least three books: Spalding’s Winter Sports (1913, 1917), Canoeing and Camping (1915), and Figure Skating for Women (1921, 1922). He also contributed a chapter on artificial lures to The Basses: Freshwater and Marine (1905). In addition to his writing, Cruikshank was involved in public speaking, doing talks on outdoor sports sometimes illustrated by motion pictures. An avid photographer, Cruikshank’s photos often featured in his illustrated lectures, his articles, and his books, as he encouraged readers to take their own cameras out-of-doors. He had a home in the Catskills as well as a home and offices in New York City, and in the 1930s he helped found the Hudson River Yachting Association. At one point, he managed the Rockefeller Center ice skating rink, and another in Rye, NY. His wife Alice was also an avid camper and hiker, and they often traveled together. In 1909, Alice went “viral” in newspapers around the country by being the first person to blaze a trail between Mount Field and Mount Wiley in the White Mountains of New Hampshire (James brought up the rear). James and Alice eventually moved to Drexel, PA and were vacationing in Lake Placid in July of 1957 when James died unexpectedly at the age of 88. Tune in next week for the final chapter!

If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today! Editor's Note: The following is a verbatim transcription of a chapter from Spalding's Winter Sports by James A. Cruikshank, published in 1917 and part of the Ray Ruge Collection at the Hudson River Maritime Museum. Many thanks to volunteer Adam Kaplan for transcribing this booklet. Where winter is at all reliable, and snow and ice can be confidently counted upon in advance, no outdoor festival of the whole year will furnish such invariable delight as the winter carnival. There seems to be some unique quality about winter which stimulates to merriment and enthusiasm. It is something more than the scientific fact that one-seventh more oxygen is found in the cold air of winter than in the warm air of summer. The same group of young people will reveal in winter depths of fun and prankish tendencies unsuspected by any actions of the summer time. Staid matrons have been known to try the turkey trot on snowshoes who never tried it anywhere else; and contributing thereby entertainment which neither they nor their friends ever before suspected them capable of. Nobody stands about in wallflower pose when the winter carnival is on. Canada started the world on the winter carnival. And then, because some of the thoughtless folks whom she desired as settlers and immigrants got the mistaken idea that Canada was a land of snow and ice, she suddenly dropped the thing. Now, with a better knowledge of her magnificent climate spread abroad all over the world, she has sensibly gone back to the enjoyment of those delightful and exhilarating winter pastimes which no other people on earth know so well how to arrange and participate in, and she again welcomes the seeker after winter joys. There is inspiration and information for every lover of winter joys in even the briefest visit to the Dominion during the couple of cold months of the year. Perhaps the presence there of so much of the French gayety and vivacity reveals the secret of her wonderful success in the carnivals of winter. But Canada is no longer the exclusive authority upon the enjoyment of winter. Switzerland, Norway, and some parts of the United States are but little behind in fostering the winter carnival. it is an unquestioned truth that nowhere in the world is there larger interest in winter pastimes than in the United States. Country clubs, outdoor organizations of all kinds, even groups of serious folks interested primarily in the betterment of the locality or the town in which they live, and in some few cases town governments themselves, are now aware of the delightful vacations which may be enjoyed by merely taking advantage of the local presence of cold weather and snow. On Long Island, New York State, in recent years there has been an illustration of this spirit to the extent of closing the schools when the big bob-sled races with the neighboring town take place, just as in sunny California the schools are often closed when snow falls in order to let the youngsters revel in its unusual beauty. All a big winter carnival needs, given the right sort of winter, is a moving spirit. Let somebody start the thing and the expression of interest will be immediate, and support will be generous. The very novelty of the affair will attract attention and draw people. And once it has been successfully carried out there will be large demands for its repetition. The famous ice palaces of Montreal, with their accompanying picturesque carnivals, did not die for lack of interest or patronage; they were killed intentionally, because they carried a wrong impression to the balance of the world. In time they will be revived. An ice palace sounds elaborate and difficult, but it need be neither. Blocks of ice or a foundation of a wooden structure upon which streams of water are played may be employed to create a structure big enough for the sport of attack and defense by armies on snowshoes and skiis, carrying torches and burning red fire. Exceedingly interesting effects can be obtained at very slight expense, providing of course that the local weather man can be relied upon to furnish his part in the program. There may be moonlight snowshoe tramps over the hills, snowshoe races where start and finish are in front of a grand-stand, or in the center of a rink, where folks can keep moving, ski races and ski coasting, skating exhibitions, costume skating with prizes for the best costume representative of winter; skating races, couple skating in fancy movements or speed contests, fancy dancing on skates, individual and couple; parade of decorated sleighs, floats, sleds, or toboggans; parades of snowshoers, ski runners, and skaters in costume. Any number of most interesting events can be run off on an ice field, such as hoop races, wheelbarrow races, potato races, snow shovel races, where the men drag the girls one-half the distance and the girls drag the men the other half; night-shirt races, where the girls aid the men to get into a night-shirt, the men skate a short distance and then the girls aid them to get out of the night-shirt; necktie and cigarette races in similar fashion; ski races, where the men or women are drawn by horses; snowshoe obstacle races, getting through a barrel, over a fence, climbing a rope ladder; toboggan races, in which two persons sit on the toboggan and propel it by hands or feet over the ice; and lanterns of all kinds everywhere, electric illumination. If it can be arranged, colored fire, torches, toboggans rigged with tiny batteries and carrying individual insignia and emblems, costumes similarly lighted, topped off by the moonlight. AuthorJames A. Cruikshank was an expert on outdoors sports during the first half of the 20th century. Born in Scotland but spending most of his life in New York, he was the editor of The American Angler magazine, Field and Stream, and wrote numerous articles for a wide variety of other magazines and newspapers throughout his career, including the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. He also published at least three books: Spalding’s Winter Sports (1913, 1917), Canoeing and Camping (1915), and Figure Skating for Women (1921, 1922). He also contributed a chapter on artificial lures to The Basses: Freshwater and Marine (1905). In addition to his writing, Cruikshank was involved in public speaking, doing talks on outdoor sports sometimes illustrated by motion pictures. An avid photographer, Cruikshank’s photos often featured in his illustrated lectures, his articles, and his books, as he encouraged readers to take their own cameras out-of-doors. He had a home in the Catskills as well as a home and offices in New York City, and in the 1930s he helped found the Hudson River Yachting Association. At one point, he managed the Rockefeller Center ice skating rink, and another in Rye, NY. His wife Alice was also an avid camper and hiker, and they often traveled together. In 1909, Alice went “viral” in newspapers around the country by being the first person to blaze a trail between Mount Field and Mount Wiley in the White Mountains of New Hampshire (James brought up the rear). James and Alice eventually moved to Drexel, PA and were vacationing in Lake Placid in July of 1957 when James died unexpectedly at the age of 88. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's Note: The following is a verbatim transcription of a chapter from Spalding's Winter Sports by James A. Cruikshank, published in 1917 and part of the Ray Ruge Collection at the Hudson River Maritime Museum. Many thanks to volunteer Adam Kaplan for transcribing this booklet. Hockey, played on ice, is one of the most fascinating and spectacular games so far devised by the sport loving people of the north. It owes its origin to the Canadians, and was probably a development of Indian games played between Indians and white men. Perhaps no winter sport of the day draws such crowds of spectators or rouses such enthusiasm as a Hockey match between two rival teams from nearby Canadian cities, and the beauty of the game lies largely in the fact that even without technical understanding of the rules, the spectators fully appreciate the spirited play. Hockey may be regarded as the Canadian national game, and it is spreading very rapidly throughout the northern parts of the United States and among many of the winter sport centers of Europe. A hockey field should be 112 feet in length by 58 feet wide. At the ends of this field goal posts, 4 feet in height and 6 feet apart, are erected. Teams consist of seven players each. The necessary implements for the sport are hockey sticks with long handles and flat curved blades, disks of vulcanized rubber called the “puck,” 1 inch thick and 3 inches in diameter. The game is divided into halves of twenty minutes’ duration each, with an intermission. The positions of the seven players are indicated by the names goal-tend, point, cover-point, rover, center, and right and left wings. The rules are very simple. Minor changes in them occur from season to season, and the latest, as published in the Spalding Athletic Library on Ice Hockey, should be consulted. There is penalty for offside play, as in foot ball. Roughness which characterized the early history of the game has been almost entirely eliminated. Speed, endurance, judgement, and skill are now placed above strength, body checking, or interference. The best players of the day are the cleanest players, and are rarely injured or penalized. The game becomes faster and more scientific every season, and team play increases over former individual play. Teams made up of women are organized among skating enthusiasts and there is increasing interest in active participation in this fine sport by the skilled women skaters of the Dominion and of American and Swiss skating centers. The roarin’ Scotch game of Curling seems steadily to hold its own in spite of its age, the competition of many new forms of winter entertainment and the fact that it is far from spectacular. Among experts, it is claimed that the game is actually increasing in popularity throughout the northern climes where winter means good ice and steady cold. There are over twenty-five affiliated clubs in the Grand National Curling Club of the United States, and in Canada there are many hundreds of clubs, some under royal patronage. The Royal Caledonian Curling Club, with King George V as its patron, is the leading organization. A field of ice, which must be very smooth and 42 yards in length by 10 yards in width, forms the curling ground. Concentric rings, 3 in number, being 2 feet, 4 feet and 7 feet from the center or tee, are drawn on the ice 38 yards from each other. A central line is drawn from tee to tee, also cross lines known as “hog scores,” “sweeping scores,” “back score” and “middle score.” The “hog score” is placed one-sixth of the entire length of the playing field. The stones are of granite, highly polished, not over 44 pounds in weight, nor over 36 inches in circumference. There are two teams of four men each in a game and the absolute dictator of the play is the “skip,” or leader, of each team. The “besom,” or broom, plays a most important part in the game, for with it the speed of the stone may be increased or checked, and to a certain measure even the direction may be altered. With every stone played, a “head” is said to be completed, and an agreed number of “heads” constitutes a game. To the young people of this day, whose lives have not brought them into contact with this ancient and quaint Scottish game, with a written history running back nearly a thousand years, Curling may seem to lack the elements of physical activity and athletic movement, but it makes up fully in the charming humors of the game, merry sallies of wit and picturesque turns of speech. Nor is the handling of 40-pound stones the child’s play which the uninitiated may think. The latest rules and records of the game will be found in the Spalding Athletic Library volume devoted to the game of Curling. There are a number of interesting and sprightly games which can be played on an ice field in addition to Hockey and Curling. Every ocean traveler is familiar with the fun of shuffleboard as played on the Atlantic liners, and merely the suggestion of its usefulness as a winter sport is needed to bring it into its rightful place in winter sport programs. There are certain general customs in regard to playing the game which may or may not be followed. The very elasticity of the methods of play renders the game especially suited to those places where some sort of impromptu sport can be arranged in which everybody can take part. Shuffleboard, as played on the ice, would best please everybody taking part in the game if made simple as to rules and equipment. The only necessary equipment consists of a set of wooden disks, about 4 inches in diameter and at least 1 inch thick, and the sticks for shoving the disks, which should be about 5 feet in length and furnished with a Y-shaped or half round end which may be part of the stick or fastened to it securely. The disks are shoved, not struck, from a standing position at each tee, toward the concentric circles marked on the ice at the other tee, or into one of nine squares marked out as a tee. These squares may be numbered with reference to the difficulty of their achievement with the disk. Squares of penalty, or “minus” squares are often placed in front. Two, four or more persons may play the game, partners may be chosen, and so tees should be anywhere from 25 to 50 feet apart, the distance being determined by the condition of the ice. Women become very expert at this thoroughly interesting winter pastime. AuthorJames A. Cruikshank was an expert on outdoors sports during the first half of the 20th century. Born in Scotland but spending most of his life in New York, he was the editor of The American Angler magazine, Field and Stream, and wrote numerous articles for a wide variety of other magazines and newspapers throughout his career, including the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. He also published at least three books: Spalding’s Winter Sports (1913, 1917), Canoeing and Camping (1915), and Figure Skating for Women (1921, 1922). He also contributed a chapter on artificial lures to The Basses: Freshwater and Marine (1905). In addition to his writing, Cruikshank was involved in public speaking, doing talks on outdoor sports sometimes illustrated by motion pictures. An avid photographer, Cruikshank’s photos often featured in his illustrated lectures, his articles, and his books, as he encouraged readers to take their own cameras out-of-doors. He had a home in the Catskills as well as a home and offices in New York City, and in the 1930s he helped found the Hudson River Yachting Association. At one point, he managed the Rockefeller Center ice skating rink, and another in Rye, NY. His wife Alice was also an avid camper and hiker, and they often traveled together. In 1909, Alice went “viral” in newspapers around the country by being the first person to blaze a trail between Mount Field and Mount Wiley in the White Mountains of New Hampshire (James brought up the rear). James and Alice eventually moved to Drexel, PA and were vacationing in Lake Placid in July of 1957 when James died unexpectedly at the age of 88. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's Note: The following is a verbatim transcription of a chapter from Spalding's Winter Sports by James A. Cruikshank, published in 1917 and part of the Ray Ruge Collection at the Hudson River Maritime Museum. Many thanks to volunteer Adam Kaplan for transcribing this booklet. The Canadians, winter lovers that they are, have given the world one of its finest implements for winter sport in the light, dainty, and marvelously swift toboggan. Probably no device of equal weight ever invented by man has attained such speed with such a load of valuable human lives. And when the end of the run is reached the thing can be picked up, tucked under an arm and carried back to the starting point; in fact that is the way in which many of the toboggans are returned to the starting point of some of the greatest runs in the world. “Zit! Walk a mile!” said a traveled Chinaman in describing his first impression of the sport. The strictly Canadian model toboggan is now made in the United States as well as in Canada. There have been practically no changes in the design which the Dominion first chose for the famous slides at Mount Royal, Montreal, Quebec, or Ottawa. Since the Indian fashioned the first toboggan with which to drag his winter’s catch of furs out to the nearest Hudson Bay post, the method of construction has changed but little. The uses of the frail chariot are distinctively different, however; now it serves to convey precious freight of charming, red-cheeked women down precipitous artificial slides on pleasure bent, where once it stood for carry-all and moving van for the taciturn nomads of the great white silences. Basswood or ash strips, from four to ten in number, are used in making a toboggan. The length may be anywhere from 5 to 9 feet and the bottom may be either flat, or there may be runners of wood or steel, usually three in number. Steel shod toboggans are a comparative novelty and fitted only for slides where ice is used; they are barred on many slides, owing to their speed, and they are not adapted to general use on snow. Toboggans can be successfully used on ordinary natural slides found on snow clad hillsides, either on crusted snow or even on loose snow if it is sufficiently packed. But the customary use of the toboggan is now found on artificial slides, or slides in which the natural slope of the land is combined with an artificial starting incline. Many country clubs have erected such slides, the most famous being that erected by the Ardsley Country Club, Ardsley, N.Y. Another very interesting illustration of how natural and artificial conditions may be combined to furnish a successful field for this fine sport, is found in the arrangement which prevails at the Lake Placid Club, Essex County, N.Y. This famous Adirondack club may be said to be a pioneer in winter sports, since it has been serving its members with such entertainment during every winter since 1902. The toboggan slide here starts from the roof of the golf house, an effective and novel way of getting immediate elevation for a good start, and the run is over a quarter of a mile in length with a drop of 114 feet. The slide at Quebec, which starts from the Citadel and runs down to the Dufferin Terrace, in front of the magnificent Chateau Frontenac, is the best illustration of a wholly artificial slide in this country or perhaps in the world. There are many private artificial toboggan slides in the United States, one of the most successful being that on the property of Mr. George D. Barron, Rye, N.Y., which was erected for the pleasure of his two daughters. The framework is of steel; a drop of nearly 70 feet is attained before the level of the field is reached and then the slide runs off in a board trough until it comes to a spreading meadow. The slide at the Ardsley Country Club, Ardsley, N.Y., has been extremely successful and has been liberally copied elsewhere. Here the plan of renting the privilege of using the slide for less than a dollar an hour per person has been the means of paying the entire cost of the experiment besides furnishing great sport for the members and their friends. Wherever possible the Canadian plan of having at least two slides side by side, separated by a snow bank of about a foot in height, will be found to greatly add to the interest. Toboggans can then be started simultaneously and the zest of competition in speed added to the thrill of swift descent. On the Mount Royal slide in Montreal there are five slides along each other, and when five toboggans loaded to their capacity start at once the sport is fast and furious. It is important that no toboggan be started on any slide until the party ahead sic seen to be out in the open field or free from possible collision. The bob-sled or “double runner” consists of fastening together two low sleds by means of a board. The cost of such an outfit ranges from five to five hundred dollars, and the five dollar rig will give almost as much sport as its expensive cousin. Steering is done by means of a wheel, like an automobile, controlling the front sled, or by means of ropes run through pulleys and held in the hand; this latter is the custom on Swiss slides. There are very few natural slides adapted to the bob-sled in this country, although there is great sport every winter in the competitions held between the coasting teams of several towns on Long Island, N.Y., and there is no reason why the sport should not become widely popular where towns are willing to devote certain roads or streets to the sport, as they do abroad. Handsome bob-sleds, cushioned in velvet and steered like a motor car, are drawn by horses and are capacious enough to carry twenty or more persons. The greatest bob-sled sport in the world is found on the famous “Cresta Run” in St. Moritz, Switzerland, or the equally famous “Kloster Run” in the town of Davos, Switzerland. Both of these wonderful coasts are over two miles in length, are on ordinary post roads set aside for the sport at certain seasons, and attract thousands of visitors from all over the world. Usually there is plenty of snow during the winter season at these resorts; when there is, the courses are built up at certain curves with great embankments of snow on which water is sprayed and then the resulting ice makes the course for much of its length a sheet of glass. At all intersecting roads there are danger signals set as the coaster starts from the top, and even the mail sleighs respect the sport. Speed of over ninety miles an hour is made on certain parts of these runs. The “Cresta Run” is regarded as the most difficult and the most interesting; one place in it known as the “Battledore and Shuttlecock” is probably the most superb piece of coasting ever built. At the close of the run there is a wonderful leap through the air which carries sled and rider 50 to 60 feet. The start and finish are timed by threads broken by the sled which thereby starts and stops a timing clock. Single sleds, of the pattern known to Americans as skeleton or clipper sleds, are generally used, having steel runners, open sides and big cushions set well back toward the end of the seat. Bob-sleds are also used on some of these runs and are occasionally steered by women. Pet dogs can be trained successfully to drag small toboggans or sleds just as the famous “huskie” dogs of Alaska do. The use of dogs for dragging snow vehicles is by no means limited to the wild wastes of Alaska, however. There are many dogs so used in the Adirondacks and in Canada. The famous dog team owned by Lord Minto, which was kept in Quebec several winters, was the means of initiating thousands of Americans into the sport of Dog Sledding. And the world famous races of dog teams dragging great loads, which Jack London has immortalized in his dramatic stories of the far north, are recalled by every lover of winter life in the silent places. A small dog sled is useful not merely as a vehicle for dogs to drag; it is the easiest way for man to carry any considerable load. The simplest pattern is a flat toboggan, generally of three strips of very thin basswood, ash or cedar, and in the case of the Indian made type is put together entirely without nails or screws of any kind, rawhide thongs taking their place. A one-man toboggan should not be over 4 feet in length and about 12 to 14 inches wide at the front and 2 inches narrower at the tail. The Indians make such a toboggan, and of this size, which weighs less than 3 pounds. A very simple and very efficient sled for either man or dog to drag is made from a couple of barrel staves on which a flat board is fastened in such fashion as to permanently preserve the full bend of the staves, then a back piece is fastened at right angles to the bottom board and braces run from the front of the bottom board to the top of the back board. A cross piece should be fastened at the front end of the staves and on this a whiffletree can be set; not until a man tries dragging a load with and without a whiffletree does he realize its value. AuthorJames A. Cruikshank was an expert on outdoors sports during the first half of the 20th century. Born in Scotland but spending most of his life in New York, he was the editor of The American Angler magazine, Field and Stream, and wrote numerous articles for a wide variety of other magazines and newspapers throughout his career, including the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. He also published at least three books: Spalding’s Winter Sports (1913, 1917), Canoeing and Camping (1915), and Figure Skating for Women (1921, 1922). He also contributed a chapter on artificial lures to The Basses: Freshwater and Marine (1905). In addition to his writing, Cruikshank was involved in public speaking, doing talks on outdoor sports sometimes illustrated by motion pictures. An avid photographer, Cruikshank’s photos often featured in his illustrated lectures, his articles, and his books, as he encouraged readers to take their own cameras out-of-doors. He had a home in the Catskills as well as a home and offices in New York City, and in the 1930s he helped found the Hudson River Yachting Association. At one point, he managed the Rockefeller Center ice skating rink, and another in Rye, NY. His wife Alice was also an avid camper and hiker, and they often traveled together. In 1909, Alice went “viral” in newspapers around the country by being the first person to blaze a trail between Mount Field and Mount Wiley in the White Mountains of New Hampshire (James brought up the rear). James and Alice eventually moved to Drexel, PA and were vacationing in Lake Placid in July of 1957 when James died unexpectedly at the age of 88. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's Note: Editor's Note: The following is a verbatim transcription of a chapter from Spalding's Winter Sports by James A. Cruikshank, published in 1917 and part of the Ray Ruge Collection at the Hudson River Maritime Museum. Many thanks to volunteer Adam Kaplan for transcribing this booklet. Please also note, this historic book chapter contains damaging stereotypes of Indigenous people. Like most inventions having to do with physical comfort, probably the snowshoe was a lazy man’s gift to the race. We can imagine how he found that by bandaging boughs on his moccasins feet he could get about with less trouble than his fellows; the idea spread, the boughs took form, then webbing was run across bows of wood and the snowshoe came into being. Every locality has its own special snowshoe, ranging from the eleven foot models of the Alaskans to the flat boards with cross pieces of the Italian dwellers of the Apennines. And each special model, far from being just subject for ridicule by the folks of any other locality, proves itself to be peculiarly adapted to the needs of the place in which it is found. Therein lies the lesson of all the new implements of the now popular winter sports; they must be adapted to the special localities in which they are to be used or the fullest measure of sport cannot be had. The Indian of the north prefers black or yellow birch for the bows of his snowshoes. Failing that wood of the right quality he selects ash, out of which the best of the snowshoes sold in large cities are generally fashioned. The webbing is preferably of caribou hide, but as there is very little caribou hide available the webbing is generally made bow cow hide for the important center and lamb skin for the filling of toe and tail piece. Properly treated and regularly painted with a good varnish these materials are entirely satisfactory for the most critical of snowshoe users. As a matter of fact the best snowshoes today are made by white men, not by Indians, just as the white man has come to make better canoes than the Indian ever made. The snowshoes sold at fair price by the leading dealers are thoroughly equal to any service they could be asked to give and will outwear several pairs of the Indian make. The webbing of the center is carried around the bow of the snowshoe, while that of the toe and tail is passed through small holes bored in the bow. Where the webbing is passed through the bows, little knots of worsted are used to break the knife-like cut of the crusted snow- not because they look pretty, as many folks think. The making of a pair of snowshoes takes the best part of several days, even with the aids of civilization, while among the Indian tribes of the far north several months elapse between the time when the first tree was felled for the bows to the day of the finished product, including stretching of the skins, warping of the bows, lacing of the webbing and drying out. The size of the snowshoe as well as its pattern depends largely upon the size and weight of the wearer, and the uses to which the snowshoe is to be put. For racing purposes the Alaskans use a snowshoe of 11 feet in length. The Montagnais beaux use a snowshoe of 36 inches in width. The trappers of the Rocky Mountains use a small “bear paw” snowshoe almost round in shape, and the best general snowshoe for the eastern part of the North American continent is the Algonquin or “club” pattern ranging from 40 to 50 inches in length and from 12 to 14 inches in width. The “bear paw” pattern is excellent for brush and hill country. The size of the mesh is governed by the average quality of the snow; when the snow is fine and dry and feathery a small mesh is desirable, while in damp and moist snow the mesh should be larger. Fastening the snowshoe to the foot is an important matter. Even the Indians and the trappers of the far north wanted to borrow or buy the ingenious American snowshoe sandal which I had attached to my snowshoes during a recent winter wolf hunting trip. These firm practical bindings are far and away superior to the lamp-wicking thongs or leather strings formerly used, especially when the walking is over hilly country, and the sag of the binding causes slipping of the foot on the snowshoe. Moccasins should be worn with snowshoes; dry tanned when the weather is very cold, say about zero, and oil tanned when it is warmer and the snow melts during the day. The binding should not be so tight as to stop the circulation nor should it come above the toe joints. An excellent device popular with the Appalachian Mountain Club of New England, on its winter outings on snowshoe, consists of a leather piece about the size of the foot attached to the under side of the snowshoe and studded with long pointed hob nails for ice creeping. There will often be times when some such device will be of the greatest value, especially in climbing crusted hillsides. The leather can be permanently attached to the snowshoe or merely tied on with rawhide thongs so as to be detachable if one wants to coast down hill on the snowshoes or does not require the additional grip on the snow. Almost anybody can learn to use snowshoes with little trouble. An hour will generally suffice the average athletic young person in which to secure sufficient ease in the use of the new toys to warrant starting off on a trip of a day or more. There are certain muscles which the sport calls into play, such as the upper thigh and the lower calf, that some folks have allowed to become weak and almost useless, but after a few days of Snowshoeing these muscles will learn their right function and cause little trouble. Correcting a wrong impression, it should be stated that the snowshoe does not really keep the walker on the top of the snow. When the snow is fine and the weather cold the snowshoe will sink in from two to five inches below the surface of the snow and the next step requires that it be lifted above the level of the snow and dragged along. This is the work which many beginners find most tedious and exhausting. The best way to save the strength of the beginners in such case is for the experts, whose muscles for the sport are in good trim, to “break trail” most of the time, thus reducing the work of the others who follow. But of course all plucky students of the sport will want in time to do their full share of the pioneering work of the leader. When the sport has been fairly learned, it is amazing how easy it becomes. Greater distances can be traveled on snowshoes in a day than any member of the party could walk on a macadamized road. This is due partly to the increased length of the stride, and partly to the easy cushion on which the foot comes to rest. Fifty and sixty miles is not an unusual day’s run for the expert snowshoer of the north. Thirty will be a good day’s work for the amateur, even after some years of experience. If packs of any kind are carried they should be of the Alpine ruck-sack pattern, consisting of a sort of loose knapsack swung over both shoulders and resting low in the back, so as not to interfere with the balance. A moonlight snowshoe walk over the hills such as is customary in Canada or in the Adirondacks, to a rendezvous where open fires are provided, either indoors or out, and hot meals are served, is a journey never to be forgotten. One of the special delights of such a party is the “Grand Bounce” which consists of tossing some member of the party into the air from the center of a blanket, the edges of which are held by a score of friends. Sometimes the blanket is dispensed with and the member thus “honored” is flung up by catching hold of arms and legs and body. One of the most famous of the pictures of this sport shows the late Frederick Remington being thus flung heavenward by his admiring friends. No sport of all the winter combines such a variety of picturesque costumes or such an international array of suitable material for the sport. For instance, the red and white and parti-colored blanket costumes are strictly Canadian in origin and history; the stockinette caps or toques are French; the socks, which are as indispensable as the snowshoes themselves, are German; the moccasins are Indian and the snowshoes, nine chances to ten, are American! AuthorJames A. Cruikshank was an expert on outdoors sports during the first half of the 20th century. Born in Scotland but spending most of his life in New York, he was the editor of The American Angler magazine, Field and Stream, and wrote numerous articles for a wide variety of other magazines and newspapers throughout his career, including the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. He also published at least three books: Spalding’s Winter Sports (1913, 1917), Canoeing and Camping (1915), and Figure Skating for Women (1921, 1922). He also contributed a chapter on artificial lures to The Basses: Freshwater and Marine (1905). In addition to his writing, Cruikshank was involved in public speaking, doing talks on outdoor sports sometimes illustrated by motion pictures. An avid photographer, Cruikshank’s photos often featured in his illustrated lectures, his articles, and his books, as he encouraged readers to take their own cameras out-of-doors. He had a home in the Catskills as well as a home and offices in New York City, and in the 1930s he helped found the Hudson River Yachting Association. At one point, he managed the Rockefeller Center ice skating rink, and another in Rye, NY. His wife Alice was also an avid camper and hiker, and they often traveled together. In 1909, Alice went “viral” in newspapers around the country by being the first person to blaze a trail between Mount Field and Mount Wiley in the White Mountains of New Hampshire (James brought up the rear). James and Alice eventually moved to Drexel, PA and were vacationing in Lake Placid in July of 1957 when James died unexpectedly at the age of 88. Tune in next week for the next chapter!

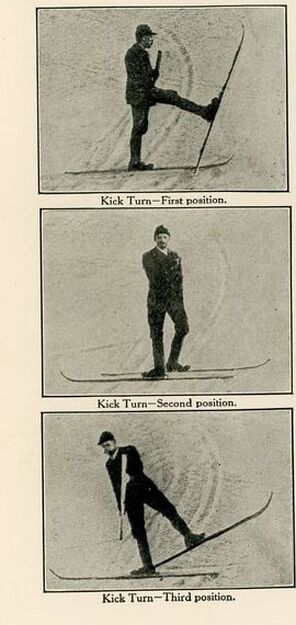

If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today! Editor's Note: The following is a verbatim transcription of a chapter from Spalding's Winter Sports by James A. Cruikshank, published in 1917 and part of the Ray Ruge Collection at the Hudson River Maritime Museum. Many thanks to volunteer Adam Kaplan for transcribing this booklet. That the spelling "skiis" is original to the text. There seems to be no doubt that the ski originated in Norway. But it is now to be found everywhere snow falls, from the extreme limits of Greenland to the summits of the Andes where South American Governments employ expert ski runners to carry mail. First as an implement of communication between nations otherwise snow bound, and now as the chosen toy of winter loving thousands it has finally come into its own. Probably no one plaything has so rapidly forged into a leading place among the sport tools of the northern races as these long and curious “planks,” as the Austrians call them. Ten years ago the ski was an interesting ethnological souvenir found only in museums; today it is hard to supply the demand for them. With that imitative and inventive skill characteristic of the Yankee, some of the best skis are now produced in the United States. They have improvements and changes peculiarly adapting them to the climate and the snow of the North American continent, and are to be preferred to the imported article in every respect. The experts of Europe, who are without doubt far in advance in the practical use of the ski, for either business or sport, have come to regard them as superior to the snowshoe for covering distance and general cruising. The armies of Northern Europe have almost exclusively adopted skiis after competitive trials of them with the Canadian snowshoe. While Norway and Austria have settled this matter by the adoption of the ski for Amy use, Canada still maintains the supremacy of the snowshoe. The battle is still on and the wise lover of winter will contribute his mite to the controversy by testing both, since there are delights to be had with each which the other does not supply. The ski is generally made of ash of the very best quality, or hickory. Some of the skiis of Northern Europe are made of elm, but the imported skiis of that wood have not proven satisfactory. Spruce has also been tried out, in Michigan, but without improvement over ash. Few of the implements for sport require such care in the making and such accuracy of design. While the expert can manage to get along on poor skiis, or crooked ones, it is the height of folly for the amateur who cares about perfecting himself in the sport to learn on anything but well made, correctly shaped and accurately balanced skiis.  "Kick Turn" first, second, and third position. Image from "Spalding's Winter Sports," by James A. Cruikshank, 1917. Ray Ruge Collection, Hudson River Maritime Museum. "Kick Turn" first, second, and third position. Image from "Spalding's Winter Sports," by James A. Cruikshank, 1917. Ray Ruge Collection, Hudson River Maritime Museum. Among the experts of the north the length of the ski is generally determined by stretching the hand over the head and selecting a pair that reach to the wrist. “Long” ski would be to where the fingers bend at the second joint; “short” ski to six inches over the head. For general use, hill climbing, touring, and even for jumping, the average or the short ski is the best. Short, stiff legged people should select a short ski, else the important kick turn cannot be executed, and on this movement depends much of the cruising ability of the ski devotee. Long skiis are best only on level stretches and flat country. There is a slight upturn at the toe of the ski made by steaming and bending the wood to a metal form. The farther north one goes, the higher this bend is generally carried. Four inches is a correct average for general use. The ski should be slightly wider at the front than at the tail. The wearer’s foot is placed about two-fifths of the distance from the tail of the ski, by which arrangement the bulk of the weight of the ski is forward of the foot. The groove is now almost universally used and runs either the full length of the bottom of the ski or to a place slightly forward of the foot. This groove tends to keep the ski straight, to steer it, so to speak, and is most important on hill descents. The foot binding is of the greatest importance. It must be rigid, yet not bind the muscles of the toes or ankle. A heavy boot is essential, or one with a very heavy sole, which is crowded or drawn firmly into the toe fastenings and then the straps fastened so they will not give. On the firmness and rigidity of the foot binding depends almost wholly the ability of the beginner to make rapid progress in the sport. There are two forms of foot bindings, the toe and the sole patterns. The sole pattern is almost unknown in the United States, although it is ranked very high by the experts of the Tyrol and the Norway chutes. The toe binding consists of a firm metal piece which is run through the ski, bent up on either side of the sole and fitted to hold the foot rigidly in place. Straps run from this metal piece over the toes and also back around the heel, being kept from slipping off the shoe by a small leather strap passing over the instep. This is the best of the toe fastenings. The usual accompaniment of the ski expert is one or sometimes two sticks used to press against the snow on the level or to steer or brake in descending hills. When but one stick is used it is generally from 6 to 8 feet in length and of bamboo; when two are used they should not be over 5 feet in length. All sticks should be equipped with leather wrist thongs and have spikes at the bottom and rings of wood firmly attached about 6 inches from the bottom. It is better for the beginner to learn with one long stick and occasionally, as he progresses in confidence, to discard the stick for considerable periods of time, so as to increase his perfection of balance. Contrary to general belief, Skiing does not require great muscular power. It is a matter of skill of balance, a knack such as one learns in swimming. For this reason it is much better to secure a teacher, if that be possible, who will at least start the beginner right and save him from learning many things which he must later unlearn. There are nice points in the sport which no type can convey, but which the eye will instantly perceive as they are executed by the expert. Failing the advantage of a teacher note these points: Do not try coasting or jumping the first thing. Much better to learn how to get up the hill, either by the hard and difficult “herringboning” method, the easier “tacking” or the simplest of all methods, “side stepping.” When you do come down remember that if the snow is damp and sticky you must lean back, while if it is dry and frozen you must lean forward. It has been wisely said that when man starts to go down hill all nature seems greased for the occasion. No man appreciates that as much as does the ski amateur. Every tree is a magnet, every stump and every rock beckons your unmanageable “planks” straight towards destruction. Study the snow, its condition, the effect of the sun on it; sometimes there is fine sport to be had on north slopes when none can be had elsewhere. Learn the sort of snow that makes for speed, for difficult climbing, for easy touring, and adapt your work for the day to the conditions. The expert ski runner knows the changing and changeableness of the snow as few men do. Snow with breaking crust is dangerous, for many reasons, while a solid crust is great sport. Avoid tracks made by others, especially in hill coasting. The fundamental things to learn in Skiing are: Darting, which simply means running downhill with skiis close together and parallel; Steering, which is done by leaning toward the side one wishes to go; Stemming, or Braking, which is done by skiis against the snow, and Slanting, which means taking a hill on an angle, a sort of “tacking downhill.” All of these movements are of almost equal importance, and should be practiced faithfully if the beginner would achieve a place in the sport or get the most fun out of it. Stemming needs but a simple diagram to explain its meaning, and Steering cannot be taught by any book; its balance is a thing which can only be learned by experience and many falls. No amount of book learning will make a ski runner expert at the sport, and the best of all the foreign books on the subject, published in the home of the sport, entirely evades the subject of Ski Jumping; nevertheless it is probable that some advice as to that important department of the sport will be welcomed. But the beginner must look more to practice than to advice. Start first without any take-off. Learn every balance with and without a pole; poles are never used in serious jumping. Gauge the stickiness of the snow and adjust your balance on arriving back on the snow after the jump to the resistance; if sticky snow, lean backward; if slippery, lean forward. Do not practice where the take-off lands you on flat ground; it is dangerous. There should be greater drop after the jump than before it. Hold your arms rigid while in the air. On touching the snow, the right foot, or one foot, should slightly precede the other.. Have the tails of the skiis touch the snow first, so as to act as rudders and get correct position. And expect ninety per cent. of falls to jumps for the first hundred jumps. Clothing for Skiing should be hard close-woven wool. Hairy goods catch the snow and soon become wet. Neck and wrists should be fitted tight and a puttee or binding of cloth about the shoe top, enclosing the long trousers or closing the opening for snow in the shoe tops is important. There is an adaptation of Skiing which is great fun and consists of employing a horse to drag the ski runners about the country, or to the top of a hill where they may coast down. Long strings of ski experts are thus met with in Norway and Switzerland, and the merriest of sport is associated with the novelty. Trips to nearby towns or places of interest can thus be made, where a meal can be had, and the return trip can be done cross country or again by horse power. AuthorJames A. Cruikshank was an expert on outdoors sports during the first half of the 20th century. Born in Scotland but spending most of his life in New York, he was the editor of The American Angler magazine, Field and Stream, and wrote numerous articles for a wide variety of other magazines and newspapers throughout his career, including the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. He also published at least three books: Spalding’s Winter Sports (1913, 1917), Canoeing and Camping (1915), and Figure Skating for Women (1921, 1922). He also contributed a chapter on artificial lures to The Basses: Freshwater and Marine (1905). In addition to his writing, Cruikshank was involved in public speaking, doing talks on outdoor sports sometimes illustrated by motion pictures. An avid photographer, Cruikshank’s photos often featured in his illustrated lectures, his articles, and his books, as he encouraged readers to take their own cameras out-of-doors. He had a home in the Catskills as well as a home and offices in New York City, and in the 1930s he helped found the Hudson River Yachting Association. At one point, he managed the Rockefeller Center ice skating rink, and another in Rye, NY. His wife Alice was also an avid camper and hiker, and they often traveled together. In 1909, Alice went “viral” in newspapers around the country by being the first person to blaze a trail between Mount Field and Mount Wiley in the White Mountains of New Hampshire (James brought up the rear). James and Alice eventually moved to Drexel, PA and were vacationing in Lake Placid in July of 1957 when James died unexpectedly at the age of 88. Skiers, what do you think? Does Cruikshank give good advice? Stay tuned for another chapter next week.

If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today! Editor's Note: The following is a verbatim transcription of a chapter from Spalding's Winter Sports by James A. Cruikshank, published in 1917 and part of the Ray Ruge Collection at the Hudson River Maritime Museum. Many thanks to volunteer Adam Kaplan for transcribing this booklet. The modern skate, briefly described, is of two kinds and several patterns. One is intended for speed skating and the other for figure skating. The best pattern for speed skating consists of a very thin, extremely hard, flat, steel blade, tapered from one-sixteenth of an inch at toe to one thirty-second of an inch at heel, fourteen and one-half and fifteen and one-half inches in length, set in a hollow steel tube, from which hollow steel supports or uprights run to the metal foot-plates, which are in turn riveted to a thin, close fitting shoe having no heel. Some of the fastest speed skaters still use the old fashioned wood top skate screwed to the heel of the shoe when the ice is reached and fastened over the toes with straps; but this pattern is rapidly going out of vogue. The hockey skate, used in that game and now of great popularity among skaters of all ages and classes and sexes, whether they play hockey or not, consists of a flat blade, with either three or four uprights or stanchions running to the metal foot-plate screwed or riveted to the shoe. The length of the blade depends upon the length of the skater’s foot. This skate is generally very slightly curved where the blade rests upon the ice, making quick turns and sharp curves possible. It is an excellent skate with which to learn the art of skating, but after the beginner has learned to feel fairly safe should be changed for the rocker skate or figure skate, if further progress in the sport of Figure Skating is an object. It is unfortunate that so many young people take up the flat-blade skate, either of the hockey or racing pattern, and then persistently stick to that pattern, since no general advancement in the achievement of curves and patterns is ever possible to the user of the flat-blade skate. Undoubtedly the best pattern for the figure skate is that which was taken to Europe by Jackson Haines, the American skater, in 1865, and adopted by almost every European skater of fame from that day to this. With the revival of skating in the United States, and especially the Continental or “fancy” style, has come a demand for a skate best suited to the graceful figures that render this form of the art so attractive. This old, yet new, skate has but two uprights or stanchions from the blade to the foot or heel plates, the blade curves over in front so as almost to touch the shoe; there is considerably greater distance from the skater’s heel to the ice than in former patterns, and larger radius of the curve of the blade where it rests upon the ice. The blade is splayed, or wider in the middle than at the toe and heel, and there are deep knife edge corrugations at the toe for pirouettes and toe movements. This is the skate which is now being used by the best skaters of the world, and the only pattern on which the larger, freer, bird-like movements so characteristic of the best skaters of Europe, are possible. It is an interesting fact that this skate is now the recognized standard of the leading instructors and experts in Figure Skating in all the prominent rinks and in theatrical attractions in which ice spectacles are a feature. Skating, whether the beginner has in mind speed or figure work, is best learned without human aid. An old, strong chair, to the legs of which have been fastened wooden runners, is the best of all devices for starting the young skater on the right balance and contributing to his self reliance and confidence. Very early in the attempts at the sport, the beginner will decide whether he is interested in Speed or Figure Skating, and he is then urged to select the correct outfit rather than adopt habits which it will be difficult later to break. There are scores of skaters now using the flat blade hockey or racing skate who will never achieve satisfactory speed, but who are peculiarly adapted to success in Figure Skating. Speed Skating is interesting for a time, and hockey is a splendid athletic game, but the figure skater has a pastime and an athletic pursuit which will interest him for a lifetime, and in which there are intricacies as fascinating as a geometrical puzzle. There are excellent books on the new forms of Figure Skating now available, the latest of which, Mr. Irving Brokaw’s “Art of Skating” and “Figure Skating for Women,” published in the Spalding Athletic Library, should be in the hands of every lover of the sport. After the beginner has attained some measure of confidence, the skate sail will be found a most interesting diversion and addition to the sport. There are many patterns of skate sails. The simplest, as well as one of the best is the rectangular pattern, fashioned of two uprights at the fore and aft ends of the sail with a cross piece as spreader. The size of this sail will depend on the designer and the sport he seeks. The average size recommended for an expert skater would be 6 to 7 feet in height and 10 to 12 feet in width. The wooden spars at the bends should be of pine or spruce, squared, thicker in the middle than at the ends, and of one piece. The center spreader may be jointed or hinged. The best material for the sail is either unbleached muslin, which is very cheap, or the best sea island cotton, known as “balloon silk.” In the sail can be set an oval or circle of celluloid as a window through which the skate sailor may watch his course. The skate sail described can be made by almost any amateur, will cost less than five dollars, and will return more sport for its cost than almost any other winter sport implement. There are many other patterns of skate sails, the next best being the triangular or pyramid shape with the base of the pyramid parallel with the skater and the long end of the sail stretching out behind. The right dimensions for such a sail for the average person will be about 9 feet for the upright spar and 10 to 12 feet for the boom. The spars can be made of heavy bamboo, and by means of a small pulley over the forward end of the boom the sail can be stretched taut. There is another foreign pattern sail which has a boom stretching across the two end spars and projecting beyond them a foot or so. Such a model requires a larger field of ice than those which have been described. Uninformed advisers recommend the flat blade skate for Skate Sailing. They are wrong, because sharp turns and curves have to be made for successful Skate Sailing. The best skate for the sport is either the regulation figure skate or a hockey skate having a curved blade. The skate sail ought to be used only where there is ample freedom; it is not adapted to small skating ponds or rinks since high speed is frequently developed, even up to thirty miles an hour, and dangerous accidents may occur. Anyone can learn the use of the skate sail with a few hours’ practice. Unlike the ice boat, which it so much resembles, tacking is done exactly the same as with a small boat, with the exception that when the sailor is ready to “come about” he simply throws the sail up over his head, makes his right angle turn into the new course and the sail comes down in correct position. It is also possible to shift the sail forward while under full speed until it is past the center, then slip it from one side of the body to the other, make the turn into the new course, and continue on the new tack. Magnificent competitive sport can be had with the skate sail by organizing “one design classes,” just as in small boat sailing, so that every sailor has similar equipment and there are no odds. Differences in weight of the contestants will be about equalized by the advantage of weight in one position of sailing as against its disadvantages in another. Women pick up the sport readily and find it most interesting. Many a woman has learned from the skate sail, for the first time, that she really can handle a sail so that she is able to get back to the place from which she started by the otherwise incomprehensible route known in yachting as “tacking.” Warm gloves, tight fitting clothing, and some sort of face protection are advisable for this sport. AuthorJames A. Cruikshank was an expert on outdoors sports during the first half of the 20th century. Born in Scotland but spending most of his life in New York, he was the editor of The American Angler magazine, Field and Stream, and wrote numerous articles for a wide variety of other magazines and newspapers throughout his career, including the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. He also published at least three books: Spalding’s Winter Sports (1913, 1917), Canoeing and Camping (1915), and Figure Skating for Women (1921, 1922). He also contributed a chapter on artificial lures to The Basses: Freshwater and Marine (1905). In addition to his writing, Cruikshank was involved in public speaking, doing talks on outdoor sports sometimes illustrated by motion pictures. An avid photographer, Cruikshank’s photos often featured in his illustrated lectures, his articles, and his books, as he encouraged readers to take their own cameras out-of-doors. He had a home in the Catskills as well as a home and offices in New York City, and in the 1930s he helped found the Hudson River Yachting Association. At one point, he managed the Rockefeller Center ice skating rink, and another in Rye, NY. His wife Alice was also an avid camper and hiker, and they often traveled together. In 1909, Alice went “viral” in newspapers around the country by being the first person to blaze a trail between Mount Field and Mount Wiley in the White Mountains of New Hampshire (James brought up the rear). James and Alice eventually moved to Drexel, PA and were vacationing in Lake Placid in July of 1957 when James died unexpectedly at the age of 88. What do you think of James A. Cruikshank's encouraging women to take up ice skating? Did you ice skate as a kid? Do you still?

Stay tuned next week for our next chapter. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today! Editor's Note: The following is a verbatim transcription of a chapter from Spalding's Winter Sports by James A. Cruikshank, published in 1917 and part of the Ray Ruge Collection at the Hudson River Maritime Museum. Many thanks to volunteer Adam Kaplan for transcribing this booklet. Pry yourself away from that steam radiator some snowy day and take a winter walk! Put behind you the mellow charm of the open fire; it will be even more delightful when you return. Hunt up a few old togs, woolen underwear, close woven woolen suit, heavy sweater, mittens, cap with ear tabs, and heavy waterproof shoes and sally forth on the quest for a new sensation. Never mind that overcoat; you will never miss it after that first half mile. And don’t forget to stuff a few crackers in your pocket for that utterly unexpected hunger which will be waiting your arrival somewhere along the road. Now, strike out! Immediately after warming up with the vigorous exercise, you feel perfectly sure that there is some sort of curious exhilaration which the air of summer never furnishes. Your imagination is not fooling you. There is one-seventh more oxygen in cold winter air than in warm summer air. That is the reason the “fire burns brighter.” And by the same token every human faculty is keener and sharper. Incidentally the falling snow carries to earth with it all floating impurities and you breathe the purest air to be found at any time of the year. You have made but a few rods when you discover that snow is the greatest artist of nature. That unsightly shack which so distressed you, has taken on forms of unknown beauty; even that ash heap, eyesore that it was, now furnishes curves of unsullied purity; the snow, like a mantle of charity, has transformed the ugly into the beautiful. Nor is its gift to the world merely pictorial. It is nature’s warm blanket. This cold, frozen thing saves the wheat and the grain from freezing; fills up the chinks between ground and farmhouse, window and frame and makes the home warmer than it was before. Close to your home, no matter where you live, the records on the snow will be found interesting and fascinating. The average city park is full of their strange story. To the open mind of the nature-lover they start all sorts of interesting speculations. Mouse, sparrow, squirrel, rabbit, fox, dog- which are they and what story do they tell? You may even find pathetic tragedies writ clear in the snow, if only you have learned to read the winter book of nature. Here see the wide sweeping record of the wings of an owl as they touched the snow on either side of the tiny tracks of a mouse. Then the prints of the wings become deeper and clearer, and here, where a little tuft of bloody fur is found, and the snow is beaten down all about, the trail suddenly ends. Perhaps the story of the fox that dined upon squirrel or partridge is spread out there full upon the ermine page of nature. Here, indeed, is a new chapter in your reading of nature’s secrets; it is stranger than any fiction and dramatic as a novel. Then sunset across the fields of white, nowhere more exquisitely beautiful. Great bloody stabs of crimson athwart the western sky. The very “souls of the trees,” as Holmes called them, when freed of their summer bodies. Across the tiny brook hurrying to sea under its arching canopy of snow-laden willow and alder. Then the open fire! No blaze so bright, no cheer so real as that which greets a winter rover fresh from a brave little ramble over the fresh snow. Take a winter walk! AuthorJames A. Cruikshank was an expert on outdoors sports during the first half of the 20th century. Born in Scotland but spending most of his life in New York, he was the editor of The American Angler magazine, Field and Stream, and wrote numerous articles for a wide variety of other magazines and newspapers throughout his career, including the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. He also published at least three books: Spalding’s Winter Sports (1913, 1917), Canoeing and Camping (1915), and Figure Skating for Women (1921, 1922). He also contributed a chapter on artificial lures to The Basses: Freshwater and Marine (1905). In addition to his writing, Cruikshank was involved in public speaking, doing talks on outdoor sports sometimes illustrated by motion pictures. An avid photographer, Cruikshank’s photos often featured in his illustrated lectures, his articles, and his books, as he encouraged readers to take their own cameras out-of-doors. He had a home in the Catskills as well as a home and offices in New York City, and in the 1930s he helped found the Hudson River Yachting Association. At one point, he managed the Rockefeller Center ice skating rink, and another in Rye, NY. His wife Alice was also an avid camper and hiker, and they often traveled together. In 1909, Alice went “viral” in newspapers around the country by being the first person to blaze a trail between Mount Field and Mount Wiley in the White Mountains of New Hampshire (James brought up the rear). James and Alice eventually moved to Drexel, PA and were vacationing in Lake Placid in July of 1957 when James died unexpectedly at the age of 88. Stay tuned next week for the next chapter of Spalding's Winter Sports.