History Blog

|

|

|

|

|

Editor’s Note: The following text is a verbatim transcription of an article featuring stories by Captain William O. Benson (1911-1986). Beginning in 1971, Benson, a retired tugboat captain, reminisced about his 40 years on the Hudson River in a regular column for the Kingston (NY) Freeman’s Sunday Tempo magazine. Captain Benson's articles were compiled and transcribed by HRMM volunteer Carl Mayer. See more of Captain Benson’s articles here. This article was originally published February 6, 1972. When steamboating was in its heyday, anyone living in Rondout, Ponckhockie, Sleightsburgh or Port Ewen never needed a clock or a watch. They could always tell what time it was by the steamboat whistles. First, there was the huge steam whistle on the Rondout Shops of the Ulster and Delaware Railroad that boatmen always said came from the big sidewheel towboat ‘‘Austin.” There would be one long whistle at 8 a.m., 12 noon, 12:30 p.m. and 4:30 p.m., telling the men at both the U. and D. shops and the Cornell Steamboat Company shops to start work, eat their noon meal and to stop for the day. When the U. and D. shops were torn down in the early thirties, this whistle was then installed on the Cornell shops. Three Long Blasts Then, every afternoon at 3:25 p.m. three long blasts of a steam whistle would be heard along Rondout Creek as either the ‘‘Benjamin B. Odell,” “Homer Ramsdell,’’ ‘‘Newburgh” or “Poughkeepsie” of the Central Hudson Line prepared to leave their dock on Ferry Street for the start of the evening trip to New York. During the summer, on Saturday mornings at 10:55 a.m., one would hear the wonderful whistle of the “Benjamin B. Odell” as she prepared to leave Rondout. Then in the evening could be heard the ‘‘Homer Ramsdell” as she came in the creek. She would blow at about 8 p.m. just as she was passing the gas plant at Ponckhockie. Every summer Sunday morning, the “Homer Ramsdell” would leave Rondout at 6:30 a.m. on an excursion to New York. The three long blasts on her whistle at 6:25 a.m. sounded twice as loud in the still morning air. From May until early October one always heard the Day Line boats blowing for the landing at Kingston Point. The one long, one short, one long blast of the down boat’s whistle was always heard just before 1 p.m. Then shortly before 2:30 p.m. would be heard the landing whistle of the north bound steamer. Phil Maines of Rondout, the former mate of the “Mary Powell,” was then the dockmaster at Kingston Point. From the ‘Tremper’ At about 10:30 a.m. on alternate days, one would hear the “Jacob H. Tremper” coming in Rondout Creek on her way to Albany. Then the next day, she would blow for Rhinecliff at 2 p.m. and by 2:45 p.m. she would be coming in the creek and blow again for Rondout. | In the evening about 8 p.m. one would hear three long whistles out in the river. One would be the Saugerties Evening Line steamer “Robert A. Snyder” or “Ida’’ blowing for their landing at Rhinecliff on their sail to New York. Before World War I, the finest sound of all was the mellow whistle of the ‘‘Mary Powell” as she prepared to leave the dock at the foot of Broadway in Rondout at 6 a.m. Then in the evening would be heard her whistle out in the river on her return from New York, just before she entered the creek. Also, all during the day at 10 minute intervals, except when stopped by ice, could be heard one short whistle from the ferry ‘‘Transport.” AuthorCaptain William Odell Benson was a life-long resident of Sleightsburgh, N.Y., where he was born on March 17, 1911, the son of the late Albert and Ida Olson Benson. He served as captain of Callanan Company tugs including Peter Callanan, and Callanan No. 1 and was an early member of the Hudson River Maritime Museum. He retained, and shared, lifelong memories of incidents and anecdotes along the Hudson River. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

0 Comments

In the early 20th century as outboard engines and motorboats were developed the Albany to New York Boat Race was a way to showcase what these engines could do. Running 136 miles from the Albany boat basin to 77nd Street in New York City, the boat race was a grueling, bone-shaking, spray-spitting marathon run. The film below is the full-length version of what has been posted many times online in shorter versions. Sponsored by Mercury Outboard Motors, the film covers the 1949 race Although little of the early history of this race has been recorded, the Hudson River Maritime Museum has a copy of a program from the New York Motor Boat Club's "First Annual Long Distance Motor Boat Race," from New York City to Albany and back again, which was held on July 3, 1909. Starting at the New York Motor Boat Club House at the foot of West 147th Street in New York City with the turnaround at a stake boat off the Albany Yacht Club House in Albany, NY, the race included the return to New York City, a distance of 270 miles. "A supply a fuel" was kept at Newburgh, Athens, and Albany for refueling. The boats had to be propelled by "explosive engine or engines operated by either gasolene [sic], kerosene, or alcohol. Any ingredient to increase the power of the fuel will not be allowed." Paid pilots and navigators were also not allowed - which meant that boat owners largely had to pilot their own vessels. Captains had to keep their own time logs, making notations as they passed prominent points, and these had to be handed in to the race committee within twelve hours of finishing the race. Interestingly, "automobile boats," which were high-speed motor launches made with automobile engines, were excluded from the race. According to the Kingston Daily Freeman, June 30, 1909, the race included "at least" 26 registrants - including six open boats, "one auxiliary sloop" and twenty cabin boats. Although we have yet to find the results of the race, on January 7, 1910, the New York Times reported on the annual meeting of the New York Motor Boat Club, writing, "As a promoter of races the Motor Boat Club has been signally successful and conspicuous, having conducted a larger number of these contests in 1909 than ever before, and exceeding in number those of many other organizations. The New York to Albany race, held in July last, was very successful, and proved so popular that it will doubtless become as fixed on the schedule of motor boat events as the Bermuda, Marblehead, and Block Island races." The race did indeed become an annual event, and by the 1920s "automobile boats" had taken over as the primary high-speed launch. It is not clear when the race ceased to be a round-trip affair and started in Albany instead of New York City, but by the mid-1920s the race was half the distance. This footage from British Pathe dates between 1929 and 1932 (the dates of Herbert Lehman's service as Lieutenant Governor of New York): The end of the footage mentions that this was the 5th annual race. The fact that the first annual race was in 1909 indicates there were several races by different motor boat clubs over the years. Motor boat racing continued to be popular into the 1970s, with advances in hydroplanes, larger engines, etc. To learn more about motor boat races like the Albany to New York Marathon, and others around the world, visit www.hydroplanehistory.com. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Welcome to Sail Freighter Fridays! This article is part of a series linked to our new exhibit: "A New Age Of Sail: The History And Future Of Sail Freight In The Hudson Valley," and tells the stories of sailing cargo ships both modern and historical, on the Hudson River and around the world. Anyone interested in how to support Sail Freight should also check out the Conference in November, and the International Windship Association's Decade of Wind Propulsion. The Ketch Nordlys is claimed to be the oldest engineless wooden sail freighter in service today, having been built in 1873 on the Isle of Wight. Though she started her career as a fishing trawler, she was converted to Sail Freight after being purchased by Fair Transport in 2014. She started coastal trading on European routes in 2015. As a Ketch, Nordlys is well suited to coastal trade. The Fore-&-Aft rig allows for sailing close to the wind, which is important when working in coastal waters. She is a small ship, only 82 feet long and carrying 25 tons of cargo. However, she is also light on crew, requiring only 5 professional crew and taking on up to 4 passengers or trainees. Her cargo is normally high value goods such as wine, whiskey, and similar products. As an engineless vessel, Nordlys is a representative of the most extreme version of Sail Freight. The majority of sail freighters have engines on board for emergency and docking use, as well as for use in crowded harbors. Nordlys, like her fleet-mate Tres Hombres, relies on the wind entirely for power, and this exposes the vessel to all the same threats and risks as sail freighters a century or more ago. While there are modern communications equipment and solar panels on board to power them, these are not a tool for propulsion. They do increase safety when interacting with other vessels, but can't shorten the time at sea if stuck in the doldrums or power the ship off a lee shore in a storm. In exchange for these disadvantages, engineless ships offer the largest carbon emissions gains, and in the case of Nordlys, even more than normal: She replaces trucks and trains instead of other ships due to her coastal trade routes, much like the far more local schooner Apollonia. You can learn more about Nordlys and Fair Transport here. AuthorSteven Woods is the Solaris and Education coordinator at HRMM. He earned his Master's degree in Resilient and Sustainable Communities at Prescott College, and wrote his thesis on the revival of Sail Freight for supplying the New York Metro Area's food needs. Steven has worked in Museums for over 20 years. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's Note: The following text is a verbatim transcription of an article written by George W. Murdock, for the Kingston (NY) Daily Freeman newspaper in the 1930s. Murdock, a veteran marine engineer, wrote a regular column. Articles transcribed by HRMM volunteer Adam Kaplan. No. 86- Shady Side ———-- Little is known of the steamboat “Shady Side” in this section of the Hudson Valley, as the territory she served on the Hudson river was within short distances of New York city. The wooden hull “Shady Side” was built at Bulls Ferry, New Jersey, in 1873 and she was powered by-an engine produced by Fletcher, Harrison and Company of New York. Her dimensions were listed as: Length of hull, 168 feet, one inch; breadth of beam, 27 feet, five inches; depth of hull, nine feet, five inches; gross tonnage, 444, net tonnage 329. Her engine was the vertical beam type with a cylinder diameter of 44 inches and an eight foot stroke. The “Shady Side” was a remarkably swift and handsome steamboat of medium size. She was built for the New York and Fort Lee passenger day line, running in line with the steamboat “Pleasant Valley.” Later she was purchased by the Morrisania Steamboat Company and in 1874 she was running in line with the steamboats “Morrisania” and “Harlem between Morrisania and New York. This line was in competition with the regular Harlem boats, “Sylvan Dell,” “Sylvan Stream,” and “Sylvan Glen,” which were in service until 1879 when the elevated railroad system in New York city began to make inroads into the steamboat passenger business and finally forced the steamboats to cease operation- being sold in 1881 under the foreclosure of mortgage. The “Shady Side” was then used in and around New York harbor until 1902 when she was placed in service on the New York-Stamford, Connecticut route. The “Harlem” and “Morrisania” were also used in New York harbor, chartered to excursion parties, and saw service on short routes from the metropolis. In the spring of 1895 the “Morrisania” was taken to Hoboken to have some repairs made. While there she caught fire and her joiner works were damaged to such an extent that it was decided not to rebuild the vessel. Her hull was then taken to Harlem and converted into a coal barge. The “Harlem,” the other vessel which ran in line with the “Shady Side” for the Morrisania Company, was sold in 1903 to a Boston concern and placed in service in Boston Harbor where she was destroyed by fire about a year later. The “Shady Side” ran on the Stamford route until 1921. Later she was sold to Marcus Garvey of the Black Star Steamship Line, who used her for excursions until the fall of 1922 when she was completely worn out. The “Shady Side” was then taken to Fort Lee on the west side of the Hudson River and beached on the mud flats- a short distance from where she had been launched a half-century before. Here she slowly decayed, the last of the great fleet of fast steamboats which ran between Harlem and New York until the elevated railroad forced the steamboats to cease operation. AuthorGeorge W. Murdock, (b. 1853-d. 1940) was a veteran marine engineer who served on the steamboats "Utica", "Sunnyside", "City of Troy", and "Mary Powell". He also helped dismantle engines in scrapped steamboats in the winter months and later in his career worked as an engineer at the brickyards in Port Ewen. In 1883 he moved to Brooklyn, NY and operated several private yachts. He ended his career working in power houses in the outer boroughs of New York City. His mother Catherine Murdock was the keeper of the Rondout Lighthouse for 50 years. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

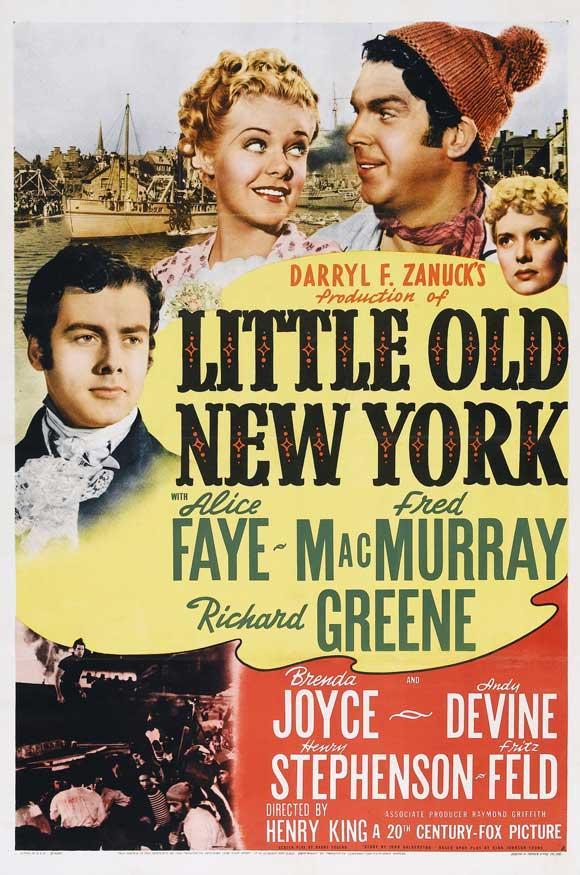

Movie poster for "Little Old New York" (1940), reading "Darryl F. Zanuck's production of Little Old New York with Alice Faye, Fred MacMurray, Richard Greene, and Brenda Joyce, Andy Devine, Henry Stephenson, Fritz Feld. Directed by Henry King, Associate producer Raymond Griffith. A 20th Century-Fox Picture." Last week we learned about the real Robert Fulton and the launching of his North River Steamboat on August 17, 1807. This week we thought we'd have a little fun with the 1940 historical drama, "Little Old New York," a fictionalized account of Robert Fulton's struggle to get his steamboat funded and in the water. The most famous scene is when local sailors, angry at the prospect of lost jobs, set the boat on fire. Like many historical dramas from the 1940s and '50s, this one is light on historical accuracy. In the film, Fulton doesn't meet Livingston until he arrives in New York. In real life, Livingston met Fulton in France in 1801 and was impressed with his work. Livingston had already been interested in steam navigation and had been given a monopoly on steam navigation in New York in 1794. Together, they financed an experimental version of the steamboat in Paris. With no success in convincing either the French or British government to adopt his design for a submarine, Fulton returned to New York in 1807 to work with Livingston on a second steamboat. That would become the Steamboat (no additional moniker was needed for the only one) which traveled the Hudson River against wind and tide in August of 1807. There is also zero evidence that Fulton received any assistance from a pretty tavern keeper in Lower Manhattan, although it makes for good storytelling. Thankfully, the film writers had her fall for sailor "Mr. Brown" instead of Fulton. Robert Fulton married Robert Livingston's niece Harriet Livingston in 1808. They went on to have a son and three daughters. Although "Little Old New York" is far from historically accurate in storyline, the producers of the film did re-create Fulton's steamboat based on historical plans. The film also reflects an early 20th century interest in the "great men" of the American past and Robert Fulton stood large in that pantheon for decades. Ultimately, his legacy of successful steam navigation did change the Hudson Valley, New York, and the world forever. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Welcome to Sail Freighter Fridays! This article is part of a series linked to our new exhibit: "A New Age Of Sail: The History And Future Of Sail Freight In The Hudson Valley," and tells the stories of sailing cargo ships both modern and historical, on the Hudson River and around the world. Anyone interested in how to support Sail Freight should also check out the Conference in November, and the International Windship Association's Decade of Wind Propulsion. The Grain de Sail is a modern small cargo schooner, launched in 2020 and in service since, carrying wines and chocolate from France to NYC and the Caribbean. The ship can carry a total of 35 tonnes of wine with a crew of 4, and takes about three months on her circuit from France to NYC, the Caribbean, and back. The plans are to have her make two circuits per year, one in spring and one in the fall, and has completed three voyages thus far. In 2021, Grain de Sail and Apollonia met up in New York Harbor and transferred cargo between the boats, one of the first such exchanges between inland and transoceanic sailing vessels in US Waters this century. Grain de Sail is unique, in that she is specifically designed for hauling wine. Her hold is climate controlled, the wines are types suited to the rolling motions of the ship, and other considerations have been made to ensure the wine is not damaged by transport. She is a Marconni-Rigged Schooner, using more modern designs of soft sails than the traditional gaff-rigged schooners which are iconic parts of the Downeast Maine seascape. These allow sailing slightly closer to the wind, and they make automated sail handling far easier. Roller-Furling replaces much of the crew labor in reefing or handling jibs and headsails, and sheets can be controlled remotely. While she has an engine onboard for emergency and docking use, she uses it very rarely. You can learn a bit more about Grain de Sail on their website: www.graindesailwines.com AuthorSteven Woods is the Solaris and Education coordinator at HRMM. He earned his Master's degree in Resilient and Sustainable Communities at Prescott College, and wrote his thesis on the revival of Sail Freight for supplying the New York Metro Area's food needs. Steven has worked in Museums for over 20 years. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's note: The following text was originally published in New-York Mercury, February 4, 1765. Thanks to volunteer researcher George A. Thompson for finding, cataloging and transcribing this article. The language, spelling and grammar of the article reflects the time period when it was written. On Friday 25th Jan. last, about 3 o’Clock Mr. Brookman of this town, one Thomas Slack, and a Negro of Mr. Remden’s, went off in a boat in order to shoot some water fowl, which during this hard weather have come in great numbers into the open places in the harbour, and having wounded some, pursued them till they got entangled in the ice, so that they were not able to get to land. Their distress being seen from the shore here, a boat with several hands put off to their assistance, but night coming on lost sight of them, and returned. – Mean while the people in the ice drove with the tide as far as Red-Hook, and fired several guns as signals of distress. The guns were heard on shore, but no assistance could be given them. And as the weather was extreamly cold, it was thought they would all have perished, -- which they themselves also expected. In this extremity they had recourse to every expedient in their power: There happened to be an iron pot and an ax on board – they cut off a piece of the boat roap and pick’d it to oakum, and putting it in the pan of a gun with some powder, catched it on fire, which with some thin pieces cut from the mast, they kindled in the pot, and then cut up their mast, seats, &c. for fewel, and making a tent of their sail, wrapt themselves as well as they could; when they found themselves nearly overcome with the cold, notwithstanding their fire, they exercised themselves with wresting, which proved a very happy expedient, restored their natural warmth, and no doubt greatly contributed to their preservation. In this manner they passed the whole night, in which they suffered much cold, but happily escaped with life, and without being frost bitten: Next morning, by firing guns, they were discovered in the ice by Mr. Seabring on Long Island, who, by laying planks on the ice for near a quarter of a mile, which otherwise was not strong enough to bear a man’s weight, they all got safe on shore, without the least hurt, and returned the same day to York. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

On August 17, 1807, Robert Fulton launched the "Steamboat" in New York City, bound for Albany, NY. Funded by founding father Robert Livingston (whose estate at Clermont became the home port of the steamboat), the "Steamboat" made the voyage north in 32 hours. Learn more about the background behind this first voyage below. Although Fulton was not the inventor of the steamboat, or even the first to launch a successful steamboat, he and Livingston were the first to turn a profit making passenger runs. Therefore it was Fulton's sidewheel design that would go onto dominate designs of Hudson River steamboats and others for decades to come. If you'd like to see a scale replica of Fulton's North River Steamboat, visit the Hudson River Maritime Museum to see our newly-acquired, six-foot-long model in the East Gallery. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Welcome to Sail Freighter Fridays! This article is part of a series linked to our new exhibit: "A New Age Of Sail: The History And Future Of Sail Freight In The Hudson Valley," and tells the stories of sailing cargo ships both modern and historical, on the Hudson River and around the world. Anyone interested in how to support Sail Freight should also check out the Conference in November, and the International Windship Association's Decade of Wind Propulsion. The wooden Brigantine Tres Hombres was launched in the Netherlands in 1943, and served initially as a fishing boat. After her first career, she sat idle until 2007, when she was purchased by three friends intent on reviving sail freight. After a two year restoration, she was relaunched in 2009, and began her sail freight career. One of the early pioneers of transatlantic sail freight, Tres Hombres was one of the vessels which paved the way for others, proving the commercial viability of sail freight for high-value cargoes. Now, Grain de Sail has taken on this model with newly built sail freighters designed for carrying wine and chocolate, as just one example of follow-on movements from the Tres Hombres. Tres Hombres can carry 40 tons of cargo, mostly coffee, chocolate, rum, and other high-value items from the Caribbean to Europe. As an engineless vessel, she is a truly zero-emission vessel, and has made 12 transatlantic circuits since 2009. She is also involved with coastal trade in Europe, rebuilding coastal trade relationships which have fallen away in the last 80-100 years. With a crew of 7 and 8 additional trainees, Tres Hombres serves as a training vessel alongside moving cargo. This will be a big advantage to the Sail Freight movement, as her Brigantine rig combines both Square-Rig and Fore-And-Aft rig sailing, allowing for trainees to become familiar with both types of traditional rig. These trainees will be needed when they complete the program to crew other sail freighters in construction or planning, such as Ceiba, Brigantes, Hawaila, and the EcoClipper Fleet. You can learn more about Tres Hombres and the FairTransport company at https://fairtransport.eu/. The webpage also includes her sailing schedule, and how to sign up to sail as a trainee. AuthorSteven Woods is the Solaris and Education coordinator at HRMM. He earned his Master's degree in Resilient and Sustainable Communities at Prescott College, and wrote his thesis on the revival of Sail Freight for supplying the New York Metro Area's food needs. Steven has worked in Museums for over 20 years. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

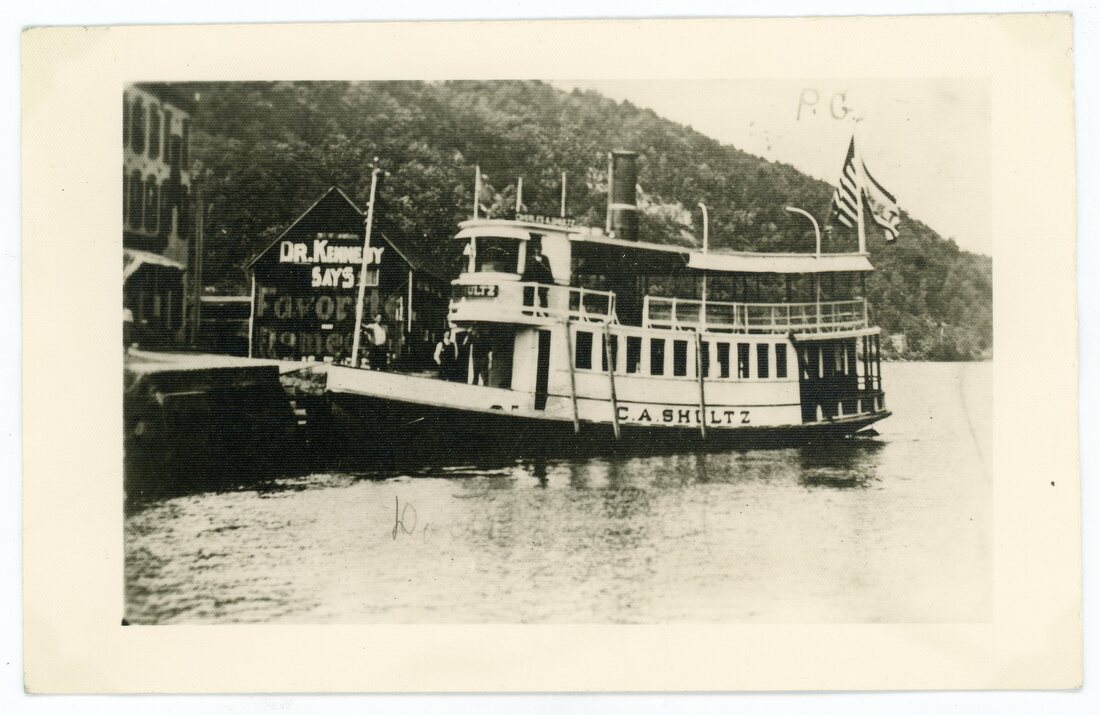

Steamboat "C.A. Shultz" - The small passenger steamer, “C.A. Schultz”, was one of a group of boats operating on the Rondout Creek, 1880s to 1920. She would leave from Rondout and stop at hamlets like Wilbur, Eddyville and South Rondout (Connelly). Tracey I Brooks Collection, Hudson River Maritime Museum. As important to the Hudson’s transportation infrastructure as the express steamers that plied from major towns and cities to New York were the local steamboats- called “yachts” - which connected many riverside villages with these major localities. They were the buses of a bygone era, from the 1870s to about 1920. The network of local routes was the lifeblood of the villages, which were isolated from the centers of commerce like Newburgh, Poughkeepsie, Rondout/Kingston, and Hudson- and too small to merit a landing by the larger steamers. The “yachts” were small propeller steamboats carrying on average about a hundred passengers. Typically they were two-decked craft, 60 to 80 feet in length, propelled by a minuscule engine to which steam was fed by an equally small boiler. The small steamers maintained a fixed schedule during the months when the river was free of ice. During their off-hours, they might be chartered for an excursion by a local organization like a volunteer firemen’s association. Rondout was the base of operations for the vessels that operated to Glasco and Malden (near Saugerties), downriver to Poughkeepsie, and along the Rondout Creek on which one could venture as far as Eddyville by boat. The upriver towns of Caymans, Coxsackie, New Baltimore, and other points were way landings on a web of routes between Hudson and Albany and on to Troy. Similar routes were maintained out of Newburgh and other downriver locations. At Rondout, vessels like Augustus J. Phillips, Charles T. Coutant, Edwin B. Gardner, Glenerie (later Elihu Bunker), Henry A. Hater, John McCausland, Kingston, Morris Block and others maintained these local services, providing for the transportation needs of many residents and businesses along the creek and in the small riverside villages and hamlets. With the construction of paved roads and the popularization of the bus and motor car for transportation in the 1920s, the era of the “yachts” on the river came to a close. One by one the yachts were dismantled or otherwise left the routes over which they had been so much a part of life along the Hudson. No longer would the daily routine on the river be punctuated by the whistles of the “yachts” as they made their frequent landings. Want to recreate a bit of the small passenger "yacht" experience? Take a ride on "Solaris"! https://www.hrmm.org/all-boat-tours.html AuthorThis article was written by William duBarry Thomas and originally published in the 2008 Pilot Log. Thank you to Hudson River Maritime Museum volunteer Adam Kaplan for transcribing the article. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

|

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 [email protected] Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |