History Blog

|

|

|

|

|

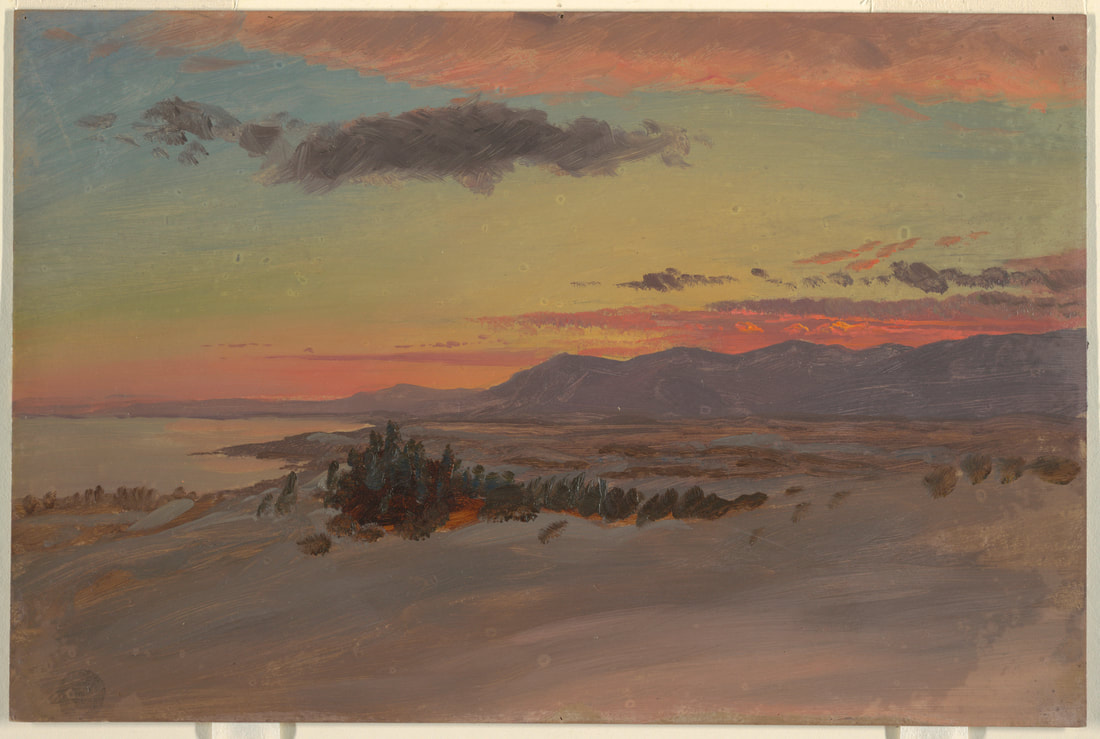

The book American Husbandry. Containing an ACCOUNT of the SOIL, CLIMATE, PRODUCTION, and AGRICULTURE, of the BRITISH COLONIES in NORTH AMERICA and the WEST-INDIES; with Observations on the Advantages and Disadvantages of settling in them, compared with GREAT BRITAIN and IRELAND was published in Britain in 1775, and written, anonymously, "by an American." It is a fascinating little piece - an attempt to convince Britons of the superiority of American soil, beauty, and even the Hudson River, to that of England. Of particular interest to us in the Hudson Valley, of course, is the chapter specifically on New York. The chapter begins with a discussion of climate and the various types of soils suitable (or not) for agriculture, often comparing New York to New England, which perhaps was more familiar to Britons at the time. But of course, the thing that caught our eye the most, was the description of the Hudson River: "The river Hudson which is navigable to Albany, and of such a breadth and depth as to carry large sloops, which its branches on both sides, intersect the whole country, and render it both pleasant and convenient. The banks of this great river have a prodigious variety; in some places there are gently swelling hills, covered with plantations and farms; in others towering mountains spread over with thick forests: here you have nothing but abrupt rocks of vast magnitude, which seem shivered in two to let the river pass the immense clefts; there you see cultivated vales, bounded by hanging forests, and the distant view completed by the Blue Mountains raising their heads above the clouds. In the midst of this variety of scenery, of such grand and expressing character the river Hudson flows, equal in many places to the Thames at London, and in some much broader. The shores of the American rivers are too often a line of swamps and marshes; that of Hudson is not without them, but in general it passes through a fine, high, dry and bold country, which is equally beautiful and wholesome."  Drawing, Hudson Valley in Winter, Looking Southwest from Olana, Frederic Church, 1870-1880. A snow covered plain is shown in the foreground and right middle distance. The Catskill mountains stretch from the right toward the left distance. Part of the Hudson River is shown in the left middle distance. The sky has light clouds with orange above the mountains and along upper edge. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. "They sow their wheat in autumn, with better success than in spring: this custom they pursue even about Albany, in the northern parts of the province, where the winters are very severe. The ice there in the river Hudson is commonly three or four feet thick. When professor Kalm [Peter or Pehr Kalm, who visited in 1747] was here, the inhabitants of Albany crossed it the third of April with six pair of horses. The ice commonly dissolves at that place about the end of March, or the beginning of April. On the 16th of November the yachts are put up, and about the beginning or middle of April they are in motion again." The chapter ends with a discussion of New York's agriculture, which grains were commonly planted where, the role of beer and hard "cyder" in everyday life, and all the possible agricultural goods and raw materials that could be exported. Of American Husbandry, the British Royal Collection Trust writes, "Written anonymously by 'An American', this is a remarkable work on the climate, soil and agriculture of the British colonies in North America immediately prior to the outbreak of the American War of Independence. It covers all the major British possessions, starting in Canada, before moving through the thirteen colonies, the Caribbean and the newly-acquired territories in Ohio and Florida. It looks, not only at the environment of these colonies, but also at which plants have been successfully cultivated, demographics, the value of different commodities to Britain and recommendations on how to improve farming methods. "Beyond the bulk of the text there are numerous references to the unsettled state of affairs in the region and the threat of an American declaration of independence, and the author dedicates the final two chapters of the second volume to the subject. Interestingly, he implies that independence is inevitable, being just a matter of time until the colonies would outgrow the mother-country, be it through population, commerce or grievance, but suggests several methods to postpone it such as: the acquisition of the French-held Louisiana territory beyond the Mississippi river or the establishment of a political union between Britain and America with the representation of American politicians in Parliament." The fact that this book was published on the eve of the American Revolution is remarkable. The First Continental Congress had already sent its first "Petition to the King" to call for the repeal of the "Intolerable Acts" (also known as the "Coercive Acts") in 1774. The Intolerable Acts were a series of punitive reactions to the Boston Tea Party, closing Massachusetts' ports, revoking its charter, extraditing colonial government officials accused of a crime back to Britain (where they faced friendlier juries), and quartering British soldiers in civilian homes. The petition was ignored and the Intolerable Acts were not repealed. In July of 1775, the Second Continental Congress penned and approved what is now known as the "Olive Branch Petition," which was delivered to London in September, 1775. A controversial last ditch effort to avoid war with Great Britain, this petition also failed, leading to the Declaration of Independence in 1776. Against the backdrop of this political, social, and economic turmoil, American Husbandry becomes that much more interesting. A largely glowing report of the settlement prospects of the American colonies, it attempted to persuade immigration and investment, even as the two nations it sought to unite - the British Empire and the soon-to-be-new nation, the United States - were on the brink of war. One wonders - were any Britons influenced by this book, choosing to emigrate during this turbulent time? If so, which side of the conflict did they adopt in their new home? We may never know. If you'd like to read the whole book, or the chapter on New York for yourself, you can find the full text of American Husbandry here. AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson is the Director of Exhibits & Outreach at the Hudson River Maritime Museum, where she has worked since 2012. She has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

0 Comments

Editor’s Note: The following text is a verbatim transcription of an article featuring stories by Captain William O. Benson (1911-1986). Beginning in 1971, Benson, a retired tugboat captain, reminisced about his 40 years on the Hudson River in a regular column for the Kingston (NY) Freeman’s Sunday Tempo magazine. Captain Benson's articles were compiled and transcribed by HRMM volunteer Carl Mayer. See more of Captain Benson’s articles here. This article was originally published April 23, 1972. In the early spring of 1934, I was on the tugboat Lion of the Cornell Steamboat Company. We were going up through Haverstraw Bay with a large up river tow. The tug Edwin Terry was our helper. It was about 9 a.m. and I was off watch and fast asleep in my bunk, when Dan Reilly, the deckhand, came to my room and called me, saying “Hey, Bill, I thought you would want to get up and see your old pal coming down the river. I jumped up as quickly as I could and there just below Stony Point, I could see the old Day Liner Albany paddling her way down river for the last time. She had been sold and was leaving the Hudson forever. The Albany was the first steamboat I had ever worked on, beginning as a deckhand during the seasons of 1928 and 1929. An April Day It was the kind of spring day that made one glad he was alive. There was a light breeze from the south with the bright April sun shimmering on the water. How wide the Albany looked as she approached us with her broad overhanging guards! I could see her paddle wheels turning under the guards, and the buckets dipping slowly in the water as she reduced speed to pass our tow and reduce the size of the waves. As she neared us with her large silver walking beam rhythmically going up and down, up and down, up and down as if reaching out ahead all the time, and her big white paddle wheels turning slowly, she was indeed a sight to behold. But little did the old girl know she was leaving her beloved Hudson River for the last time to sail on another river to the south under another name. When she was almost next to us, I gave the Albany the one long, one short whistle signal – a pilot’s way of saying hello. She answered with one long and two short blasts on her whistle. Joe Eigo of Port Ewen, the captain of the Terry, did the same – and the Albany also answered him. The Last Goodbye I hollered over to Joe Eigo, the Terry being abreast of us on a head line and also pulling on the tow, “Give her the goodbye, will you Joe, because I want to give her the last goodbye.” Joe answered, “Sure, Bill,” and really pulled down hard on the Terry’s steam whistle with three long blasts, which the Albany answered. By this time, the Albany was down abreast of the tow. Then with the Lion’s heavy bass horn, I blew three very long whistles to say farewell. The Albany answered with three equally long blasts on the whistle. I can still see the white steam from her whistle ascending skyward in the bright sunlight of that April morning. I knew this would be the last time I would ever hear that old familiar whistle. I watched her as she went further and further down river, around Rockland Lake, and finally out of sight. At the time, I was sure I would never see her again… and I never did. There is something that reaches far into a man who once worked on a steamboat of the past, particularly when he comes into contact with the first boat on which he worked. From the Shore If, for example, he should decide to take a job ashore – and if one of the early boats he worked should happen to go by, he will always watch her with fond nostalgia until she disappears from view. And many memories and thoughts pass through his mind. That’s the way it was with me that day I saw the Albany go by for the last time. I thought of all the old crew members, all the passengers I had seen on board her – sometimes as many as 3,000, all the landings we had made up and down the river for the last time, leaving behind forever her old winter berth at Sleightsburgh, her recent lay up dock at Athens, and the landings she knew so well for so long. Henry Briggs of Kingston had been the Albany’s last captain. On her last trip down the Hudson, however, Captain Briggs was in Florida, so Captain Alonzo Sickles of the Hendrick Hudson, also of Kingston, took her to New York. Alexander Hickey was pilot, Charles Maines of Kingston was mate and Charles Requa was chief engineer on her final trip. The Albany had originally been built in 1880 and, until the coming of the Hendrick Hudson in 1906, ran regularly on the New York to Albany run. From 1907 until the Washington Irving came out in 1913, the Albany was used almost exclusively on the New York to Poughkeepsie route. Then, she replaced the Mary Powell on the Rondout to New York run and covered this service until it was ended in September 1917. During the 1920’s, except on weekends, the Albany was used almost entirely for charters or as an extra boat. Last Year on Hudson The season of 1930 was to be the last regular season in service for the Albany on the Hudson River. At that time she had been an active member of the Day Line fleet for 51 seasons, a record that was not to be exceeded by any other Day Line. In September, she went into winter lay up as usual at the Sunflower Dock at Sleightsburgh. However, with the deepening of the Great Depression, it was decided not to put her in operation in 1931, and – in May of that year – the tugboat S. L. Crosby of the Cornell Steamboat Company towed her from Sleightsburgh to Athens to a more permanent lay up berth. I was a deckhand on the Crosby when we towed her on her last up river trip. In 1933 the Hudson River Day Line went into receivership – and on March 6, 1934 – the Albany was sold at public auction. She was purchased by B. B. Wills of Baltimore for only $25,000 and he planned to place her in service on the Potomac River running out of Washington, D.C. When I saw her on that April day in 1934, the Albany was on her way to her new life in the south. She was renamed Potomac and continued in operation out of Washington until the end of the season of 1948. She was then dismantled and her hull converted into a barge named Ware River. The old Albany was always a fast steamboat and, even in her last years on the Hudson River, she could still show her speed to much newer steamboats. As the Potomac in her new service in the south, she still took smoke from no other steamboat. AuthorCaptain William Odell Benson was a life-long resident of Sleightsburgh, N.Y., where he was born on March 17, 1911, the son of the late Albert and Ida Olson Benson. He served as captain of Callanan Company tugs including Peter Callanan, and Callanan No. 1 and was an early member of the Hudson River Maritime Museum. He retained, and shared, lifelong memories of incidents and anecdotes along the Hudson River. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

These images show examples of fishing camps along the Hudson River. Sturgeon and shad were both prized for their caviar. Sturgeon is a prehistoric fish that can grow up to 15 feet and weigh up to 800 pounds. In the 18th and 19th centuries, sturgeon meat was so plentiful it was nicknamed "Albany Beef". A 40 year sturgeon fishing moratorium was declared in 1998 in an effort to restore the sturgeon population. Shad, a type of herring, live most of their lives in the Atlantic Ocean, returning in the spring to spawn in the freshwater rivers of their birth. A very bony fish with flavorful meat, filleting shad is an art. Shad weigh between 3 and 8 pounds. Female shad are valued for their eggs to make caviar. Hudson River commercial fishing came to a halt in the 1970s. More on that here. Visit the Hudson River Commercial Fishing Oral Histories at New York Heritage to learn more. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

On April 17, 2012, singer-songwriter Dar Williams released the album "In the Time of Gods." Most of the songs on the album were based on the mythology of ancient Greece, but one song seems to have slipped by - "Storm King," based on the beauty and legend of Storm King Mountain at Cornwall, NY.

"Storm King" Lyrics

The clouds will form a crown, Circling the rocky mountaintop, Telling us the rain is coming soon, As we sail the river up and down The storm king has borne the seasons all, Worn them upon his brow, He guides the watchful boats below, I am the storm king now. He is bemused, sometimes delighted, Sees the trains, the hikers on the hill In our progress and our industry May we grow better still. The storm king has seen us from above, Rising up on the starboard bow He knows the turning of the years I am the storm king now. The storm king has borne the seasons all, Worn them upon his brow, He guides the watchful boats below, I am the storm king now. I am the storm king now. And for those of you who love Dar Williams for the poetry of her songwriting, Hank Beukema has combined Williams' two Hudson River songs - "The Hudson" and "Storm King" into one beautiful, spoken-word video. Which is your favorite? We think both Dar's song and the poetry of the lyrics as read by Hank are equally beautiful! Thanks to HRMM volunteer Mark Heller for sharing his knowledge of Hudson River music history for this series.

If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's Note: The following text is a verbatim transcription of an article written by George W. Murdock, for the Kingston (NY) Daily Freeman newspaper in the 1930s. Murdock, a veteran marine engineer, wrote a regular column. Articles transcribed by HRMM volunteer Adam Kaplan. See more of Murdock's articles in "Steamboat Biographies". See more Sunday News here. No. 61- Benjamin B. Odell The 264 foot steamer, “Benjamin B. Odell”, was built for the Central Hudson Steamboat Company for service on the Hudson River, and made her first trip on April 10, 1911. She was capable of making over 20 knots an hour and was one of the finest boats of her type on the Hudson river. The main deck was set aside for freight, but there was a quarter deck passenger entrance with the purser’s office and auxiliary smoking room at one side. Broad stairs led from the deck to the main saloon above. In the extreme after end of the deckhouse was located the kitchen. The grand saloon of the “Odell” was made up of two decks, fore and aft, with galleries. On the fourth or hurricane deck was an observation room. The “Benjamin B. Odell” had 63 staterooms and 126 berths. These staterooms were all outside rooms with two windows apiece and were furnished in very comfortable manner. The dining room was located on the third deck, extending the full width of the cabin and containing 20 tables seating 100 people. The pilot house of the “Odell” was large and fully equipped, having both hand and steam steering wheels independent of one another. The captain’s room was directly aft of the pilot house with a door connecting, and built like that of an ocean liner. Although originally built for night service between New York and Rondout, the “Odell” was capable of being used on day excursions and her license called for 2,533 passengers when she was carrying freight. Without cargo, her capacity was rated as 3,050 passengers. The “Benjamin B. Odell” was commanded by F.L. Simpson, who was promoted from the “William F. Romer”, where he had been in charge for eight years. On Friday, February 26, 1937, as the “Benjamin B. Odell” laid at the Rosoff dock at Marlborough where it had been tied up for the winter season, a mysterious fire completely destroyed the huge steamer. Today she still lies at the dock, a charred mass of twisted and tangled wreckage, a sad reminder of the once fine steamboat of the Hudson. AuthorGeorge W. Murdock, (b. 1853-d. 1940) was a veteran marine engineer who served on the steamboats "Utica", "Sunnyside", "City of Troy", and "Mary Powell". He also helped dismantle engines in scrapped steamboats in the winter months and later in his career worked as an engineer at the brickyards in Port Ewen. In 1883 he moved to Brooklyn, NY and operated several private yachts. He ended his career working in power houses in the outer boroughs of New York City. His mother Catherine Murdock was the keeper of the Rondout Lighthouse for 50 years. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Welcome to Week 2 of the #HudsonRiverscapes Photo Contest! We asked members of the public to submit their best photos (no people) of the Hudson River, and just look at all the beautiful shots they delivered. We are delighted to share with you these wonderful images of our beloved Hudson River. If you would like to submit your own photos to this contest, you can find out more about the rules - and prizes! - here. This is a contest, but all voting takes place on Facebook. To vote, simply log into your account, click the button below, and like and/or comment on your favorite. At the end of each week, the photo with the most likes and comments wins a Household Membership to the Hudson River Maritime Museum. If you don't get to vote this week, keep liking and commenting anyway - all photos are entered into the Grand Prize at the end of the contest - a free private charter aboard Solaris for 2021! Thank you for everyone who participated in this first week! If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Congratulations to our landslide winner for Week 1 of the Hudson Riverscapes Photo Contest - Mark Heller! Mark's photo, "Northbound Tug and Barge Breaking Through the Morning Mist, Port Ewen" had over 200 likes, and over 80 comments and shares. Congratulations, Mark! Since Mark is already a member of the Hudson River Maritime Museum, he will have the option to give his membership away. You can continue to like, comment, and share all of your favorite photos on Facebook - all photos in the contest are eligible for the grand prize of a free private charter aboard Solaris in 2021. If you would like to submit your own photos to this contest, you can find out more about the rules - and prizes! - here. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor’s note: Twenty years ago, four friends with an abiding love of the Hudson River and its history stepped away from their families and their work to travel up the river in a homemade strip-planked canoe to experience the river on its most intimate terms. The team set off from Liberty State Park in New Jersey and completed the adventure nine days later just below Albany where one of the paddlers lived. They began with no itinerary and no pre-arranged lodging or shore support. There were no cell phones. The journey deepened their appreciation for the river and its many moods, the people who live and work beside the river and the importance of friendship in sustaining our lives. Please join us vicariously on this excellent adventure. We'll be posting every Friday for the next several weeks, so stay tuned! Follow the adventure here. ThursdayMid-Hudson Valley I woke up to heavy dew at 4:30 AM, cleaned up and began packing. The others rose from their fitful rest at 5:00. We were anxious to catch the flood tide. We fixed some oatmeal, broke camp and were paddling north before sunrise. We hailed the canal cruise ship Niagara Princess and rounded Danskammer Point, named by early Dutch travelers who are said to have witnessed council fires and native dancing on the promontory. Moments later, we witnessed the sun rise above the concrete silos and steel conveyors of the stone crusher on the east shore. Shifting tugs were already arranging barges at the plant and the sun’s long rays were described in sharp focus by the omnipresent clouds of dust. The crusher plant here and the power plant at Danskammer Point are two of the most obnoxious blights on the river between the Highlands and Catskill. We reached the Pirate Canoe Club a mile south of Poughkeepsie at 7:45 AM just as the current turned against us. After tying up, we walked to the clubhouse and asked the members at the bar if we could stay until the tide turned. They graciously welcomed us and put on a fresh pot of coffee. They served the coffee with donuts and we watched Good Morning America and the Weather Channel on the TV set over the bar. Hurricane Dennis was still stalled off Cape Hatteras. Our hosts were proud to tell us about the origins of their club. It was established along Poughkeepsie’s central waterfront but was forced to relocate as a result of urban renewal. The new clubhouse was perched on a rock jutting out into the river. The docks were connected to the clubhouse by a series of wooden gangways and stairs and there was an overturned canoe inscribed with the club’s name hanging near the entrance road coming into the club. Although founded as a canoe club, powered craft prevailed along the docks. The club had an old crane for seasonally placing and removing dock sections. Membership was inexpensive by any standard. The drinks here were cheap too. Dan, Steve and Joe decided to walk into town and I stayed behind to organize our gear and to draw and write. A north breeze began to blow and with it, the humidity began to dissipate. An older club member came by in his kayak and visited with me for a while and I asked him about camping on Esopus Island. He thought it would be fine and told me that there was a landing place on the southeast side where we could draw our canoe up onto the island. My partners returned at 11:00 with fresh vegetables for supper and a book for Dan. Joe was elated to have fresh ingredients for tonight’s supper. We had lunch on the hill and caught the beginning of the flood tide at 2:00. Soon, we passed beneath the Wizard of Oz-like Poughkeepsie suspension bridge and the long abandoned railroad bridge keeping close to shore in order to get the most out of the favorable current. We came abreast of the Culinary Institute of America and bantered with two students enjoying the river. They bragged that they could cook better than any of us and offered to prove it by preparing some fish for dinner if we could only catch some. We hadn’t brought any fishing gear and sadly couldn’t take them up on this offer. We continued north through the Lange Rack and past Crum Elbow and the Hyde Park train station. Esopus Island was visible straight ahead. We found the landing place on the southeast side amidst dwarfed cedar trees and climbed out at 4:30. After scouting the island we decided to camp here. We unloaded the canoe and then took her out light to explore the island’s shoreline all the way around. Our circumnavigation complete, we set up our camp and more thoroughly explored the island. We found evidence of the island’s history; flint flakes discarded near the river during the process of making tools and weapons, the remnants of a low stone wall perhaps intended to contain sheep, stone foundations for an early aid to navigation and fragments of the sidewheel steamer Point Comfort which failed to see the island and ran up on it early in 1919. There was also plenty of poison ivy and lots of red ants. The island’s vegetation was severely dried out as a result of a hot dry summer and the thin soil covering the island. Many leaves had fallen and those which hadn’t were brown. It was very reminiscent of an Indian summer in October. We were well north of the leading edge of the salt line and took this opportunity to thoroughly bathe in the river. Once clean, we began dinner. Dan and I sketched the scene in our journals. Dinner was served at sunset and included a massive fresh vegetable salad with radicchio, noodles with spaghetti sauce and fried Spam. We cleaned up at 9:00 and sat around the campfire for a while listening to the din of birds and crickets and sharing our thoughts about the trip. A turkey vulture circled overhead. We reflected upon the subtle unfolding of the river and its surroundings and distant views experienced by travelers in both directions. Joe aptly described our adventure as “a kaleidoscope of marvelous experiences that seemed to glide from one to another.” Some big birds tramped around our camp with heavy feet at night. In the morning, we found what appeared to be a pterodactyl egg on the bluff east of our campsite. It dawned upon us that we had built our camp at the intersection of a busy network of blue heron paths. Don't forget to join us again next Friday for Day 6 of the trip! AuthorMuddy Paddle’s love of the Hudson River goes back to childhood when he brought dead fish home, boarded foreign freighters to learn how they operated and wandered along the river shore in search of the river’s history. He has traveled the river often, aboard tugboats, sailing vessels large and small and canoes. The account of this trip was kept in a small illustrated journal kept dry within a sealed plastic bag. The illustrations accompanying this account were prepared by the author. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Last week, we discussed the impacts of cholera and yellow fever on Rondout in the 1830s and ‘40s, but New York City underwent similar epidemics throughout the early 19th century. At the same time, rising population in New York City, as well as efforts to fill in its brackish wetlands and shorelines, was creating a problem with the water table and pollution. Fresh drinking water was becoming more and more scarce in the growing city and natural water sources were increasingly contaminated by sewage and industrial wastes. Enter a pie-in-the-sky idea for yet another enormous engineering marvel (New York’s canals being the previous pipedreams turned reality) – the Croton Aqueduct. The idea was simple – pipe clean water from the relatively unspoiled Croton River through gravity-fed aqueducts to New York City. Aqueducts were certainly not a new idea – the Romans had invented them, after all – but to construct something on this scale was a rather startling idea. Following the cholera epidemic of 1832, Major David Bates Douglass, an engineering professor at West Point and one of a new school of civil engineers, surveyed the proposed route in 1833. Bates was an excellent surveyor, but had proposed no practical plans for physical structures, and so was fired in 1835. As early as 1835, before construction even began, the project was gaining national attention. An article from the Alexandria Gazette (Richmond, VA) from December 25, 1835 discussed the plan, writing, “In carrying into effect the contemplated plan of supplying the City of New York with water from the Croton River, an aqueduct, we believe, is necessary across one of the rivers. If this is so, the experience gained to that city and the county in submarine architecture, by the works now going on at the Potomac Aqueduct in connexion with the Alexandria Canal, will be invaluable.” December, 1835 gave New York City another reason to want abundant supplies of water – the Great Fire of New York of 1835 wiped out most of New York City and bankrupted all but three of its fire insurance companies. The fire would spur a number of reforms, including an end to wooden buildings (a boon for the Hudson Valley’s brick, cement, and bluestone industries). But many wondered, had the aqueduct already been in place, if more of the city would have been saved. John B. Jervis, who cut his teeth on the construction of the Erie, D&H, and Chenango canals as well as early railroads, became Chief Engineer on the Croton Aqueduct project in 1836, and construction began the following year. The Croton River was dammed and thousands of laborers, many of them Irish, commenced digging tunnels by hand and lining them with brick. On August 22, 1838, the Vermont Telegraph published a good description of the work: “The Aqueduct which is to bring Croton river water into the city of New York, will be 40 miles long. It will have an unvarying ascent from the starting point, eight miles above Sing Sing to Harlem Heights, where it comes out at 114 feet above high water mark. A great army of men are now at work along the line, and at many points the aqueduct is completed. The bottom is an inverted arch of brick; the sides are laid with hewn stone in cement, then plastered on the inside, and then within the plaster a four inch brick wall is carried up to the stone wall, and thence the top is formed with an arch of double brick work. It will stand for ages a monument of the enterprise of the present generation.” On November 11, 1838, a newspaper in Liberty, Mississippi reported on a bricklaying contest – “In a match at brick-laying in a part of the arch of the Croton Aqueduct, between Nicholson, a young man of Connecticut, and Neagle, of Philadelphia, the latter was a head when his strength gave way, having laid 3,700 bricks in 5 ½ hours. Nicholson continued a half hour longer, when he had laid 5,350. The work was capitally done.” On September 12 of that same year, the Alexandria Gazette chimed in again, noting, “There are full four thousand men employed on the line of the Croton Aqueduct, which is to supply the city of New York with pure and wholesome water. About six of the sections will be completed this fall. The commissioners will now proceed to contract for the ‘Low Bridge’ across the Harlem river, according to the original plan. The whole, when finished, will be the most magnificent work in the United States.” The Low Bridge the Gazette referred to was originally planned to go under the Harlem River, but this was quickly abandoned. Instead, what is now known as the High Bridge was constructed in stone – its arched support pillars strongly reminiscent of Roman aqueducts. High Bridge was designed by Chief Engineer John B. Jervis and completed in 1848. It remains the oldest bridge in New York City. Indeed, the High Bridge and the whole aqueduct warranted a lengthy newspaper article – almost the whole page – August 27, 1839 edition of the New York Morning Herald. Cataloging the extant Roman aqueducts around the world, defining the difference between an aqueduct and a viaduct (aqueducts carry water across water – viaducts carry water across roads), and in all comparing the Croton Aqueduct, and especially the High Bridge, quite favorably to all its predecessors. But not all was well in construction. The Morning Herald wrote extensively of the aqueduct again on September 4, 1839 claiming, “owing to the gross mismanagement that has prevailed in the office of the water commissioners, the expense of the work has been twice as much as it ought to have been, and after all it will be very defective in many of its most important points; and independent of the immense trouble and the large sums of money that will perpetually be required to keep the whole of it in repair, we have not the least doubt that, when the work comes to be proved by passing a large body of water through it, at least one-sixth part of it will have to be pulled down and rebuilt.” The article continues on in that vein for quite some time – the principal complaint besides cost being that, unlike the Romans (who also used better quality brick and cement), the Croton Aqueduct would be largely hidden from sight, and the iron pipes would “burst upon the first pressure,” claiming that the commissioners “wanted to oblige some friend who was an iron founder, and to give him a fat contract, by which he could get rid of a quantity of old metal.” Of course, the editor of the Morning Herald seemed to have ulterior motives, as he negatively connected the Croton Aqueduct with President Martin Van Buren’s campaign for reelection in July of that year, and blamed politicking for the delays and purported graft. He also seemed to hold a grudge – the Morning Herald reported endlessly about the aqueduct, but also about purported mismanagement. No other newspaper from the era reported similar claims. However, an article in the Richmond Gazette (Richmond, VA) from July 28, 1842, does hint at the enormous cost of the project, but brings up the 1835 fire and its enormous cost as a justification for the price. At 5 A.M. on June 22, 1842, water began flowing through the Croton Aqueduct. The water commissioners, aboard the small vessel the Croton Maid of Croton Lake, went with it. The 16 foot long, four-person barge was especially built to traverse the tunnels and continued until High Bridge, which was not yet completed. On June 27, the Croton Maid was carried across the river and the commissioners continued back into the aqueduct, arriving at the York Hill Reservoir to a 38 artillery gun salute. The following day, the Board of Water Commissioners submitted a report to Robert H. Morris, the Mayor of New York City. It was printed in the New York Herald on June 25, 1842. “SIR – The Board of Water Commissioners have the honor to Report, that on Wednesday, the twenty second instant, they opened the gates of the Croton Aqueduct at its mouth, on the Croton Lake, at 5 o’clock in the morning, giving it a volume of water of 18 inches in depth. “The Commissioners, with their Chief and Principal Assistant Engineers, accompanied the water down, sometimes in their barge, ‘the Croton Maid of Croton Lake,’ and sometimes on the surface of the Aqueduct above. “We found that the water arrived at the waste gates at Sing Sing, a distance of 8 miles in 5 hours and 48 minutes: here we suffered the water to flow out at the waste gates until 12 o’clock, M., when the gates were closed on a volume of about 2 feet in depth. The water then flowed on and arrived at Mill River waste gates at a quarter past 3 o’clock, a distance of 5 miles. “It was there drawn off through the waste gates for half an hour, and was, at a quarter before 4 o’clock, allowed to flow on. We continued to precede it on land, and to accompany it in our boat, in the aqueduct, to Yonkers, a distance of 10 miles, where it arrived at half past 10 o’clock at night. Here we permitted it to flow at this waste gate until a quarter past 5 o’clock in the morning, when the waste gates were closed, and it flowed on and arrived at the waste gate on the Van Courtlandt farm, a distance of five miles and a half, in three hours and a quarter. Here we permitted it to flow out of the waste gates for two hours when the gates were closed, and it flowed, in two hours and twenty minutes, a distance of about four miles and three quarters, down to the Harlem river, where the Commissioners and their Chief Engineer emerged to the surface of the earth in their subterranean barge at 1 o’clock, June 23d. “The average current or flow of the water has been thus proved to be forty-five minutes to the mile, a velocity greater, we are happy to say, than the calculations gave reason to expect. “It is with great satisfaction we have to report, that the work at the dam, on the line of aqueduct proper, the waste gates and all the appendages of this great work, so far as tried by this performance, have been found to answer most perfectly the objects of their construction. “In conclusion, we congratulate the Common Council of the city, and our fellow citizens, at the apparent success of this magnificent undertaking, designed not for show, nor for luxury, nor for glory; but for health, security against fire, comfort, temperance [note: a reference to the habit of mixing New York water with alcohol to make it safe and palatable to drink] and enjoyment of our whole population – objects worth of a community of virtuous freemen. “With great respect, we remain, your obedient servants, Samuel Stevens, John D. Ward, Z. Ring, B. Birdsall. “P.S. – We expect the water will be admitted into the Northern Division of the Receiving Reservoir on Monday next, at half-past 4 o’clock, P.M. at which time and place we shall be happy to see yourself and the other members of the Common Council.” In fact, the water did not begin to fill the Manhattan reservoirs until July 4, 1842. The official celebration was reserved for October 14, 1842. The New York Herald reported the following day, “The celebration commenced at daylight with the roar of one hundred cannon, and all the fountains in the city immediate began to send forth the limpid stream of the Croton. Soon after this, the joyous bells from a hundred steeples pealed forth their merry notes to usher in the subsequent scenes. At and before this moment, over half a million of souls leaped simultaneously from their slumbers and their beds, and dressed themselves as for a gladsome gala day – a general jubilee.” Workers were given the day off and an enormous parade, with representatives from every official organization in the city followed, ending at City Hall Park, where an enormous fountain was flowing. Again, the New York Herald, “For several days previous, thousands of strangers had been pouring into the city from all parts of the country, to see and join in the procession, until there must have been at least 200,000 strangers in the city, making an aggregate with the resident inhabitants of half a million of souls congregated in our streets.” The opening of the Croton Aqueduct marked a period of transformation for New York City. Already one of the most important port cities in the nation, the abundance of clean water meant that urban and industrial growth could continue apace. The aqueduct was expanded several times, but in 1885 the “New Croton Aqueduct” was constructed. The Old Croton Aqueduct continued to be used until the 1950s, and is today a park – many of its old aqueduct bridges are now pedestrian bridges, as had been suggested during their original construction. The New Croton Aqueduct is still in use, still bringing Croton River water to New York City. The High Bridge across the Harlem River, completed in 1848, was threatened with demolition in the 1920s. The narrow support arches were thought to impede commercial traffic on the Harlem River, and water was no longer flowing across the bridge, instead using a tunnel drilled beneath the Harlem River (also as originally planned). Architects and preservationists fought to save the bridge and in 1927, a compromise was reached – the bridge would remain, but five of the center stone arches were replaced with a single span of steel. In 1968, the Old Croton Aqueduct State Historic Park was established to preserve the original route of the aqueduct through Westchester County. In 1992, the Old Croton Aqueduct was designated a National Historic Landmark. AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson is the Director of Exhibits & Outreach at the Hudson River Maritime Museum, where she has worked since 2012. She has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor’s Note: The following text is a verbatim transcription of an article featuring stories by Captain William O. Benson (1911-1986). Beginning in 1971, Benson, a retired tugboat captain, reminisced about his 40 years on the Hudson River in a regular column for the Kingston (NY) Freeman’s Sunday Tempo magazine. Captain Benson's articles were compiled and transcribed by HRMM volunteer Carl Mayer. For more of Captain Benson’s articles, see the “Captain Benson Articles” category. This article was originally published April 22, 1973. One evening back in the early spring of 1925, the Cornell tugboat ‘‘S. L. Crosby’’ was in Rondout Creek getting ice at the old ice house the Cornell Steamboat Company used to maintain along the creek. The ice house was located just west of where the Freeman Building now stands. At the time, another Cornell tugboat, the “Thomas Dickson" was layed up adjacent to the ice house at the rear of the Cornell office building. While taking on ice, Captain Aaron Relyea of the ‘‘Crosby” went over on the “Dickson.” Looking around in the “Dickson's” pilot house he came upon an old order dated June 1914. It read “Captain John Sheehan, tug 'Thomas Dickson’. You will pick up barge ‘Henelopen’ at the Beaver sand dock, Staatsburgh." The Beaver sand dock used to be where Norrie Point Inn is now located along the east shore of the Hudson River off the north end of Esopus Island. Even then, it hadn't been used in years. Captain Aaron thought he would have some fun. At that time, the ‘‘Crosby’’ was the helper tug on a tow going down river in charge of the tugboat “Osceola.” John Sheehan, captain of the “Thomas Dickson" in 1915, was now the captain of the "Osceola.” Darkness Falling When the ‘‘Crosby’’ came up alongside of the ‘‘Osceola’’ out in the river, darkness was falling. Captain Aaron called out to Sheehan, “John, here's an order for you" — and sent the deckhand over to “Osceola” with it. Captain Sheehan, not looking too closely at the order, got all excited and began to fume and sputter. He shouted back to Aaron, “We can't go in there for that barge; this boat draws too much water. Why, when we used to get them out with the "Dickson," we had to pull them out on a head line." "Well," Aaron replied, “they are the orders. We are to hold the tow for you.” With that, Captain Sheehan put the light on in the pilot house and read the order more carefully. It was then he finally noticed the 1914 date and the name of the tug as "Thomas Dickson" instead of ‘‘Osceola." Captain Sheehan was always a good sport. He thought it was a great joke Captain Relyea had played on him and laughed about it for days afterward. Odd Greeting Captain Sheehan also always used a rather odd form of greeting. Whenever he would be passing another boat close aboard, he would lean out of his pilot house — no matter what boat he was on — and holler over, "What do ya say, say say?’’ One would hear his booming greeting no matter what hour of the day or night. In later years, Captain Sheehan was captain of the freighter “Green Island’’ of the Hudson River Night Line running between Troy and New York. In 1934, when the Depression had tied up a lot of steamboats at their docks, he was captain of a dredging company tug by the name of "Kate Jones." One day off Van Wies Point, on her way to Albany, Captain Sheehan slumped at the wheel in her pilot house. He had suffered a heart attack and died before the tug could reach a dock. I always liked Captain Sheehan a great deal. He was an excellent boatman, one who seemed to truly enjoy his chosen profession. In a sense, it was fitting his time should come at the pilot wheel of a tugboat while underway on his beloved Hudson River. AuthorCaptain William Odell Benson was a life-long resident of Sleightsburgh, N.Y., where he was born on March 17, 1911, the son of the late Albert and Ida Olson Benson. He served as captain of Callanan Company tugs including Peter Callanan, and Callanan No. 1 and was an early member of the Hudson River Maritime Museum. He retained, and shared, lifelong memories of incidents and anecdotes along the Hudson River. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

|

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 [email protected] Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |