History Blog

|

|

|

|

|

Tomorrow is the 139th birthday of the iconic Brooklyn Bridge, which was opened to the public on May 24, 1889. At the time, it was the longest suspension bridge in the world, the first permanent crossing between Brooklyn and Manhattan, and today is the oldest bridge to Manhattan still standing. The engineering marvel was the work of John Roebling, his son Washington Roebling, and eventually was completed by Washington's wife Emily Roebling, after Washington grew too ill to continue. For the compelling story of the long, complicated, and dangerous work to complete the bridge, check out this short documentary film below: Did you know? John Roebling's pioneering work in cabled suspension bridges was honed through his work on the Delaware & Hudson Canal! To learn more about the Roebling family and their contributions to American industrial history, visit the Roebling Museum in Roebling, NJ. For more about Roebling's work on the D&H Canal, check out this talk D&H Canal Historian Bill Merchant gave for the Roebling Museum on John Roebling and the Delaware aqueducts. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

0 Comments

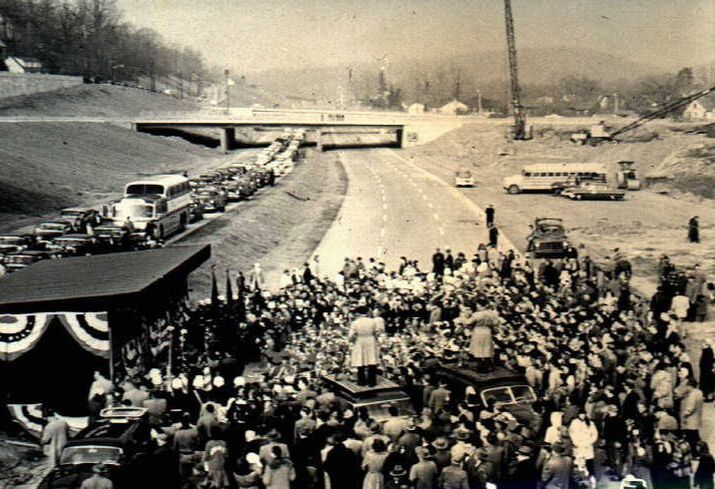

On December 15, 1955, the newly constructed Tappan Zee Bridge opened to the public. Construction began in 1952 and the bridge took 45 months to complete. It connected Nyack, NY in Rockland County on the west side of the Hudson River, and Tarrytown, NY in Westchester County on the east side of the river. It was part of a larger project constructing the Governor Thomas E. Dewey Thruway - one of the oldest interstate highway systems in the country and the longest toll road in the nation. Watch the film below, created in the 1950s and held by the New York State Archives, about the construction and opening of the bridge. The film features lots of historic footage of how construction battled and depended on water. The bridge opening was typical of many mid-20th century construction projects, featuring honored dignitaries giving speeches and throngs of people crowding to see and experience the new bridge first-hand.  December 15, 1955 South Nyack Celebration opening of the Thomas E. Dewey Thruway. Crowds gathered on a cold December 15, 1955 for the official opening of the Tappan Zee Bridge. There are flags, a color guard, and a band. Cameramen stand atop cars, surrounded by hundreds of spectators. Many cars and a bus are in line in the eastbound lane, ready to drive across the bridge. The bridge was named Tappan Zee after the Tappan tribe of Native Americans who once lived in the area - and for the Dutch zee, an open expanse of water. Later in 1994, the bridge would be renamed Governor Malcolm Wilson Tappan Zee Bridge in honor of the former governor. Photo by Dorothy Crawford, 1955. Nyack Public Library Local History Collection. The construction of the bridge dramatically changed the two communities it connected, both physically and demographically. Over 100 homes were removed or relocated via eminent domain in Nyack to make room for the Thruway and bridge, despite stiff opposition to the plan. Once the highway and the bridge were completed, both Nyack and Tarrytown, as well as neighboring communities, boomed with commuters and others seeking less expensive housing still within driving distance of New York City. To learn more about the controversies leading up to the construction of the bridge, a historical timeline, the architecture of the bridge, first-person accounts, and more, check out this online exhibit. The old Tappan Zee bridge was replaced with a new bridge and gradually demolished. Demolition was completed and the new bridge fully opened in 2018. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

On the afternoon of Tuesday, November 29, 1921, over a thousand people gathered at the Kingston, NY Armory for a celebratory dinner. The dinner was part of a whole day of celebrations around the opening of the Rondout Creek Suspension Bridge, which connected the town of Port Ewen and the City of Kingston. One of the oldest suspension bridges in New York State (it predates the Bear Mountain Bridge by 3 years), and according to an article in the Daily Freeman ("Ten Thousand Hear Governor at Rondout Creek Bridgehead," November 30, 1921), the largest suspension bridge built in the county since 1909 (no word on which other bridge was built then). The festivities included an enormous parade, speeches by New York State Governor Nathan L. Miller and other officials, and a ceremonial walk across the bridge, including a ceremonial meeting of the two towns in the middle of the bridge, represented by young women shaking hands. When the official festivities were closed, the general public was allowed to cross the bridge. So many people were crowded on either side that the Freeman reported, "So tightly was the crowd packed into a compact mass that if it had rained, few drops would have sifted through to the pavement. It is estimated there were 10,000 persons in the crowd." As nearly all the people walked across the bridge, the Freeman again commented, "It is hardly likely that the bridge will ever receive a more severe test or a heavier load." The event was followed with a fireworks display. So what's all this got to do with a shoe brush? This curious little souvenir from the Hudson River Maritime Museum archives was donated by John Wagman in 1994. A leather-backed brush meant to clean shoes or clothes, it features an image of the bridge on the back in gold and reads "Souvenir. Kingston, N.Y. Nov. 29, 1921" and below "Rondout Creek Bridge. State Highway Link to Kingston, N.Y. Catskill Mts. Ashokan Reservoir and the West." The brush was a souvenir of all who attended the celebratory dinner at the armory. The same Freeman article had this to say about the brush: "Wang Designed Brush Back. "Many who received the souvenir brush at the bridge banquet at the armory were struck with the fine design of the bridge on the back of the brush. The design was the work of C. Y. Wang, a Chinese student who is with the state highway department, who furnished the art drawing of the bridge for the brass die used to stamp in gold the bridge picture on the backs of the brushes. Mr. Wang deserves great credit for his fine work of art." Why a shoe brush was chosen as the souvenir for the event is unclear, but it may have become immediately useful to many attendees, as the Freeman also reported the prodigious amount of mud at the construction site, writing: "Plenty of Mud. "The rock cut was filled with water from the recent heavy storms and on either side of the cut the mod was deep. It was a clayey mud that made walking slippery, but thousands braved the mud to clamber up the hill and to look down upon the open space where the fireworks were set off. "Those who had not the foresight to wear rubbers were kept busy when they got home in cleaning the mud from their shoes, but what was a little mud to a good view of the really excellent display of fireworks set off by the Pain Company of New York?" Due to the weather, the bridge did not officially open to motorists until the spring. According to a Yonkers Herald article entitled "Rondout Bridge is Dedicated At Last" published December 1, 1921, "It will be a boon to motorists who have suffered long delays in crossing the slow-moving, antiquated chain ferry at Rondout." The Wurts Street Suspension Bridge, as it is often known today, turns 100 years old this year, as does this shoe brush. Happy Birthday to them both! If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

This year is the 100th anniversary of the opening of the Rondout Suspension Bridge (or the Wurts Street Bridge, the Port Ewen Bridge, or the Rondout-Port Ewen Bridge, etc!), which opened to vehicle traffic on November 29, 1921. The bridge was constructed to replace the Rondout-Port Ewen ferry Riverside, which was affectionately (or not so affectionately) known as "Skillypot," from the Dutch "skillput," meaning "tortise." Spanning such a short distance, the ferry was small, and with the advent of automobiles, only able to carry one vehicle across Rondout Creek at a time, causing long delays. Motorists advocated for the construction of a bridge, which was set to begin in 1917. But when the United States joined the First World War that spring, construction was delayed until 1921. Staff at the museum had long known that there was a woman welder on the construction crew, but we knew nothing beyond that. Had she learned to weld at a shipbuilding yard during the First World War? Was she a local resident, or someone from far away? There were more questions than answers, until a few weeks ago when HRMM volunteer researcher and contributing scholar George Thompson ran across a newspaper article that he said went "viral" in 1921. Entitled, "Woman Spider," and featured in the Morning Oregonian from Portland, Oregon, the article indicated that "Catherine Nelson, of Jersey City" was our famous woman welder. Having a name sparked off a flurry of research and the collection of 37 separate newspaper articles, all variations on the same theme. Fourteen articles were all published on the same day, September 3, 1921. But only one had more information than the rest - "Never Dizzy, Says Woman Fly, Though Welding 300 Feet in Air. Mrs. Catherine Nelson Has No Nerves, She Loves Her work and Is Paid $30 a Day," published in the Boston Globe. Which, wonderfully, included a photo of Mrs. Catherine Nelson! Here is the full article from the Boston Globe: KINGSTON, NY, Sept 3 – Three hundred feet above the surface of Rondout Creek, a worker in overalls and cap has been moving about surefootedly for several days on the preliminary structure that is to support a suspension bridge across that stream. Thousands of glances, awed and admiring, have been cast upward at the worker, stepping backward and forward and wielding an instrument that blazed blue and gold flames and welded together the cables from which the bridge will swing. “Some nerve that fellow’s got!” was a favorite remark, to which would come the reply: “You said it!” But there’s more than awe and admiration now directed aloft, for it turns out that “that fellow” is a woman – Mrs. Catherine Nelson of Jersey City, the only woman outdoor welder in the world. Isn’t Afraid of Work She isn’t afraid of her work; she loves it; and – of course this is a big inducement – she gets $30 a day for it. She has never had an accident in her seven years’ experience at the trade. She’s as strong as a man, weighing 180 pounds to her 5 ft 6 in of height, and is a good looking, altogether feminine, Scandinavian blonde. She’s 31. "I was born in Denmark and was married there," Mrs Nelson told the reporter. "But my husband died and left me with two small children, so I had to shift for myself. "For two years I worked as a stewardess on an ocean liner, but I could not have my children with me and my pay wasn’t much, so I cast about for harder and better-paid work, so I could have my own little home. "My husband was a garage keeper in Denmark, and I had worked with him, so I knew something of machinery. I got a job in a machine shop in this country. They had an electrical welding department there and I soon got a place there. I grew to love the work and I’ve been at it for seven years. Does Not Get Dizzy "This is the highest job I’ve been on, but one of my first was on a water tower at Bayonne, 225 feet tall. I’ve been on smokestacks and tanks plenty. No, I don’t get dizzy. I wear overalls and softsoled shoes, and I’m always sure of myself, for I haven’t any nerves. "I like to pride myself on the fact that I’ve never turned down a single welding job because it might be dangerous.' Showing Mrs. Nelson’s standing in her trade, it was she who was sent up from Jersey City when Terry & Tench, the bridge contractors, asked the Weehawken Welding Company for their best operator. "My children and I are happy and comfortable now,' she said; 'and I hope to afford to take them home to Denmark for Christmas. But I will come back and tackle some more welding jobs." The last published article we could find, "Says She Has No Nerves," published in the Chickasha Star, in Chickasha, Oklahoma on September 16, 1921, is almost a verbatim reprint of the Boston Globe article. As a cable welder, Catherine Nelson was responsible for welding together the cable splices that made up the longest length of the cable span. Wire cable is produced in limited sections, and often the cable was spliced together with welding, which is among the strongest of the splices, replacing the earlier versions of wire wrapping, and later screw splicing. Welded splices are stronger and more durable than both. Most welding was typically done in a shop setting, but some, as with Catherine Nelson, were done on site. She may have done additional welding while walking the cables, as most of the newspaper stories focus on her working 300 feet up in the air. Once the initial suspension cables were in place, supporting cables for the deck of the bridge could be constructed, which were designed to provide additional support, rigidity, and to spread the weight load across the entire bridge. This particular bridge is said to be unique for its "stiffening truss," located under the deck of the bridge. The bridge was opened on November 29, 1921 to great fanfare. It remains the oldest suspension bridge in the Hudson Valley, predating the longer Bear Mountain Bridge by several years. As for Catherine Nelson? We've yet to find any additional information about her, but if you have any leads, or are a relative with family stories, please let us know in the comments! AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson is the Director of Exhibits & Outreach at the Hudson River Maritime Museum, where she has worked since 2012. She has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Summer visitors at Kingston Point Park wait for a Hudson River Day Line steamer to come into port and pick them up for their journey home. The train in the background is part of the Ulster & Delaware Railroad, and is back from the Catskills, c. 1905. The U&D Railroad served as the Gateway to the Catskills transporting visitors from the Hudson River waterfront to summer resorts in the cooler Catskill Mountains. Trolley terminal at Kingston Point Park, ca. 1906. Designed by noted architect, Downing Vaux, Kingston Point Park opened in 1897. The park was financed by S.D. Coykendall, son-in-law of founder Thomas Cornell and second president of the Cornell Steamboat Company. By the 1890s the Cornell Company transportation holdings included rail as well as boats. The Ulster & Delaware Railroad extended from Kingston Point Park west into the Catskills. The Kingston City trolley system ran throughout the city and out to Kingston Point. Both rail systems were owned by the Cornell company. The park was built to provide a landing for the Hudson River Day Line and its thousands of passengers who could spend a day there or take the Ulster & Delaware Railroad from the park up to the Catskills. Before the steamboat landing at Kingston Point was built, large steamers docked across the Hudson River at Rhinecliff. Passengers took the Kingston-Rhinecliff ferry, also controlled at the time by the Cornell Steamboat Company, to reach Kingston. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Last week, we discussed the impacts of cholera and yellow fever on Rondout in the 1830s and ‘40s, but New York City underwent similar epidemics throughout the early 19th century. At the same time, rising population in New York City, as well as efforts to fill in its brackish wetlands and shorelines, was creating a problem with the water table and pollution. Fresh drinking water was becoming more and more scarce in the growing city and natural water sources were increasingly contaminated by sewage and industrial wastes. Enter a pie-in-the-sky idea for yet another enormous engineering marvel (New York’s canals being the previous pipedreams turned reality) – the Croton Aqueduct. The idea was simple – pipe clean water from the relatively unspoiled Croton River through gravity-fed aqueducts to New York City. Aqueducts were certainly not a new idea – the Romans had invented them, after all – but to construct something on this scale was a rather startling idea. Following the cholera epidemic of 1832, Major David Bates Douglass, an engineering professor at West Point and one of a new school of civil engineers, surveyed the proposed route in 1833. Bates was an excellent surveyor, but had proposed no practical plans for physical structures, and so was fired in 1835. As early as 1835, before construction even began, the project was gaining national attention. An article from the Alexandria Gazette (Richmond, VA) from December 25, 1835 discussed the plan, writing, “In carrying into effect the contemplated plan of supplying the City of New York with water from the Croton River, an aqueduct, we believe, is necessary across one of the rivers. If this is so, the experience gained to that city and the county in submarine architecture, by the works now going on at the Potomac Aqueduct in connexion with the Alexandria Canal, will be invaluable.” December, 1835 gave New York City another reason to want abundant supplies of water – the Great Fire of New York of 1835 wiped out most of New York City and bankrupted all but three of its fire insurance companies. The fire would spur a number of reforms, including an end to wooden buildings (a boon for the Hudson Valley’s brick, cement, and bluestone industries). But many wondered, had the aqueduct already been in place, if more of the city would have been saved. John B. Jervis, who cut his teeth on the construction of the Erie, D&H, and Chenango canals as well as early railroads, became Chief Engineer on the Croton Aqueduct project in 1836, and construction began the following year. The Croton River was dammed and thousands of laborers, many of them Irish, commenced digging tunnels by hand and lining them with brick. On August 22, 1838, the Vermont Telegraph published a good description of the work: “The Aqueduct which is to bring Croton river water into the city of New York, will be 40 miles long. It will have an unvarying ascent from the starting point, eight miles above Sing Sing to Harlem Heights, where it comes out at 114 feet above high water mark. A great army of men are now at work along the line, and at many points the aqueduct is completed. The bottom is an inverted arch of brick; the sides are laid with hewn stone in cement, then plastered on the inside, and then within the plaster a four inch brick wall is carried up to the stone wall, and thence the top is formed with an arch of double brick work. It will stand for ages a monument of the enterprise of the present generation.” On November 11, 1838, a newspaper in Liberty, Mississippi reported on a bricklaying contest – “In a match at brick-laying in a part of the arch of the Croton Aqueduct, between Nicholson, a young man of Connecticut, and Neagle, of Philadelphia, the latter was a head when his strength gave way, having laid 3,700 bricks in 5 ½ hours. Nicholson continued a half hour longer, when he had laid 5,350. The work was capitally done.” On September 12 of that same year, the Alexandria Gazette chimed in again, noting, “There are full four thousand men employed on the line of the Croton Aqueduct, which is to supply the city of New York with pure and wholesome water. About six of the sections will be completed this fall. The commissioners will now proceed to contract for the ‘Low Bridge’ across the Harlem river, according to the original plan. The whole, when finished, will be the most magnificent work in the United States.” The Low Bridge the Gazette referred to was originally planned to go under the Harlem River, but this was quickly abandoned. Instead, what is now known as the High Bridge was constructed in stone – its arched support pillars strongly reminiscent of Roman aqueducts. High Bridge was designed by Chief Engineer John B. Jervis and completed in 1848. It remains the oldest bridge in New York City. Indeed, the High Bridge and the whole aqueduct warranted a lengthy newspaper article – almost the whole page – August 27, 1839 edition of the New York Morning Herald. Cataloging the extant Roman aqueducts around the world, defining the difference between an aqueduct and a viaduct (aqueducts carry water across water – viaducts carry water across roads), and in all comparing the Croton Aqueduct, and especially the High Bridge, quite favorably to all its predecessors. But not all was well in construction. The Morning Herald wrote extensively of the aqueduct again on September 4, 1839 claiming, “owing to the gross mismanagement that has prevailed in the office of the water commissioners, the expense of the work has been twice as much as it ought to have been, and after all it will be very defective in many of its most important points; and independent of the immense trouble and the large sums of money that will perpetually be required to keep the whole of it in repair, we have not the least doubt that, when the work comes to be proved by passing a large body of water through it, at least one-sixth part of it will have to be pulled down and rebuilt.” The article continues on in that vein for quite some time – the principal complaint besides cost being that, unlike the Romans (who also used better quality brick and cement), the Croton Aqueduct would be largely hidden from sight, and the iron pipes would “burst upon the first pressure,” claiming that the commissioners “wanted to oblige some friend who was an iron founder, and to give him a fat contract, by which he could get rid of a quantity of old metal.” Of course, the editor of the Morning Herald seemed to have ulterior motives, as he negatively connected the Croton Aqueduct with President Martin Van Buren’s campaign for reelection in July of that year, and blamed politicking for the delays and purported graft. He also seemed to hold a grudge – the Morning Herald reported endlessly about the aqueduct, but also about purported mismanagement. No other newspaper from the era reported similar claims. However, an article in the Richmond Gazette (Richmond, VA) from July 28, 1842, does hint at the enormous cost of the project, but brings up the 1835 fire and its enormous cost as a justification for the price. At 5 A.M. on June 22, 1842, water began flowing through the Croton Aqueduct. The water commissioners, aboard the small vessel the Croton Maid of Croton Lake, went with it. The 16 foot long, four-person barge was especially built to traverse the tunnels and continued until High Bridge, which was not yet completed. On June 27, the Croton Maid was carried across the river and the commissioners continued back into the aqueduct, arriving at the York Hill Reservoir to a 38 artillery gun salute. The following day, the Board of Water Commissioners submitted a report to Robert H. Morris, the Mayor of New York City. It was printed in the New York Herald on June 25, 1842. “SIR – The Board of Water Commissioners have the honor to Report, that on Wednesday, the twenty second instant, they opened the gates of the Croton Aqueduct at its mouth, on the Croton Lake, at 5 o’clock in the morning, giving it a volume of water of 18 inches in depth. “The Commissioners, with their Chief and Principal Assistant Engineers, accompanied the water down, sometimes in their barge, ‘the Croton Maid of Croton Lake,’ and sometimes on the surface of the Aqueduct above. “We found that the water arrived at the waste gates at Sing Sing, a distance of 8 miles in 5 hours and 48 minutes: here we suffered the water to flow out at the waste gates until 12 o’clock, M., when the gates were closed on a volume of about 2 feet in depth. The water then flowed on and arrived at Mill River waste gates at a quarter past 3 o’clock, a distance of 5 miles. “It was there drawn off through the waste gates for half an hour, and was, at a quarter before 4 o’clock, allowed to flow on. We continued to precede it on land, and to accompany it in our boat, in the aqueduct, to Yonkers, a distance of 10 miles, where it arrived at half past 10 o’clock at night. Here we permitted it to flow at this waste gate until a quarter past 5 o’clock in the morning, when the waste gates were closed, and it flowed on and arrived at the waste gate on the Van Courtlandt farm, a distance of five miles and a half, in three hours and a quarter. Here we permitted it to flow out of the waste gates for two hours when the gates were closed, and it flowed, in two hours and twenty minutes, a distance of about four miles and three quarters, down to the Harlem river, where the Commissioners and their Chief Engineer emerged to the surface of the earth in their subterranean barge at 1 o’clock, June 23d. “The average current or flow of the water has been thus proved to be forty-five minutes to the mile, a velocity greater, we are happy to say, than the calculations gave reason to expect. “It is with great satisfaction we have to report, that the work at the dam, on the line of aqueduct proper, the waste gates and all the appendages of this great work, so far as tried by this performance, have been found to answer most perfectly the objects of their construction. “In conclusion, we congratulate the Common Council of the city, and our fellow citizens, at the apparent success of this magnificent undertaking, designed not for show, nor for luxury, nor for glory; but for health, security against fire, comfort, temperance [note: a reference to the habit of mixing New York water with alcohol to make it safe and palatable to drink] and enjoyment of our whole population – objects worth of a community of virtuous freemen. “With great respect, we remain, your obedient servants, Samuel Stevens, John D. Ward, Z. Ring, B. Birdsall. “P.S. – We expect the water will be admitted into the Northern Division of the Receiving Reservoir on Monday next, at half-past 4 o’clock, P.M. at which time and place we shall be happy to see yourself and the other members of the Common Council.” In fact, the water did not begin to fill the Manhattan reservoirs until July 4, 1842. The official celebration was reserved for October 14, 1842. The New York Herald reported the following day, “The celebration commenced at daylight with the roar of one hundred cannon, and all the fountains in the city immediate began to send forth the limpid stream of the Croton. Soon after this, the joyous bells from a hundred steeples pealed forth their merry notes to usher in the subsequent scenes. At and before this moment, over half a million of souls leaped simultaneously from their slumbers and their beds, and dressed themselves as for a gladsome gala day – a general jubilee.” Workers were given the day off and an enormous parade, with representatives from every official organization in the city followed, ending at City Hall Park, where an enormous fountain was flowing. Again, the New York Herald, “For several days previous, thousands of strangers had been pouring into the city from all parts of the country, to see and join in the procession, until there must have been at least 200,000 strangers in the city, making an aggregate with the resident inhabitants of half a million of souls congregated in our streets.” The opening of the Croton Aqueduct marked a period of transformation for New York City. Already one of the most important port cities in the nation, the abundance of clean water meant that urban and industrial growth could continue apace. The aqueduct was expanded several times, but in 1885 the “New Croton Aqueduct” was constructed. The Old Croton Aqueduct continued to be used until the 1950s, and is today a park – many of its old aqueduct bridges are now pedestrian bridges, as had been suggested during their original construction. The New Croton Aqueduct is still in use, still bringing Croton River water to New York City. The High Bridge across the Harlem River, completed in 1848, was threatened with demolition in the 1920s. The narrow support arches were thought to impede commercial traffic on the Harlem River, and water was no longer flowing across the bridge, instead using a tunnel drilled beneath the Harlem River (also as originally planned). Architects and preservationists fought to save the bridge and in 1927, a compromise was reached – the bridge would remain, but five of the center stone arches were replaced with a single span of steel. In 1968, the Old Croton Aqueduct State Historic Park was established to preserve the original route of the aqueduct through Westchester County. In 1992, the Old Croton Aqueduct was designated a National Historic Landmark. AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson is the Director of Exhibits & Outreach at the Hudson River Maritime Museum, where she has worked since 2012. She has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

|

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 [email protected] Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |