History Blog

|

|

|

|

|

Editor's note: The following excerpts are from "A Narrative of the Adventures and Escape of Moses Roper, from American Slavery" published 1838. Thank you to Contributing Scholar George A. Thompson for finding, cataloging and transcribing these excerpts. The language, spelling and grammar of the article reflects the time period when it was written. Learn more about Moses Roper here  Moses Roper (c. 1815 – April 15, 1891) was an African American abolitionist, author and orator. He wrote an influential narrative of his enslavement in the United States in his Narrative of the Adventures and Escape of Moses Roper from American Slavery and gave thousands of lectures in Great Britain and Ireland to inform the European public about the brutality of American slavery. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moses_Roper At that time, I had scarcely any money, and lived upon fruit, so I returned to Albany, where I could get no work, as I could not show the recommendations I possessed, which were only from slave states, and I did not wish any one to know I came from them. After a time, I went up the western canal as steward in one of the boats. When I had gone about 350 miles up the canal, I found I was going too much towards the slave states, in consequence of which, I returned to Albany, and went up the northern canal, into one of the New England states-Vermont. The distance I had travelled, including the 350 miles I had to return from the west, and the 100 to Vermont, was 2,300 miles. When I reached Vermont, I found the people very hospitable and kind; they seemed opposed to slavery, so I told them, I was a run-away slave. I hired myself to a firm in Sudbury. After I had been in Sudbury some time, the neighboring farmers told me that I had hired myself for much less money than I ought. I mentioned it to my employers, who were very angry about it; I was advised to leave by some of the people round, who thought the gentlemen I was with would write to my former master, informing him where I was, and obtain the reward fixed upon me. Fearing I should be taken, I immediately left and went into the town of Ludlow, where I met with a kind friend, Mr. _______who sent me to school for several weeks. At this time, I was advertised in the papers and was obliged to leave; I went a little way out of Ludlow to a retired place, and lived two weeks with a Mr. ________ deacon of a church at Ludlow; at this place, I could have obtained education, had it been safe to have remained. [Author's note: It would not be proper to mention any names, as a person in any of the States in America found harboring a slave, would have to pay a very heavy fine. ] From there I went to New Hampshire, where I was not safe, so went to Boston, Massachusetts, with the hope of returning to Ludlow, to which place I was much attached. At Boston, I met with a friend who kept a shop, and took me to assist him for several weeks. Here I did not consider myself safe, as persons from all parts of the country were continually coming to the shop, and I feared some might come who knew me. I now had my head shaved and bought a wig, and engaged myself to a Mr. Perkins of Brookline, three miles from Boston, where I remained about a month. Some of the family discovered that I wore a wig, and said that I was a run-away slave, but the neighbors all round thought I was a white, to prove which, I have a document in my possession to call me to military duty. The law is, that no slave or colored person performs this, but every other person in America of the age of twenty-one is called upon to perform military duty, once or twice in the year, or pay a fine. COPY OF THE DOCUMENT. "Mr. Moses Roper, You being duly enrolled as a soldier in the company, under the command of Captain Benjamin Bradley, are hereby notified and ordered to appear at the Town House in Brookline, on Friday, 28th instant, at 3 o'clock P. M., for the purpose of filling the vacancy in said Company, occasioned by the promotion of Lieut. Nathaniel M. Weeks, and of filling any other vacancy which may then and there occur in said Company, and there wait further orders. By order of the Captain, E. P. WENTWORTH, Clerk." Brookline, Aug. 14th, 1835."* I then returned to the city of Boston, to the shop were I was before. Several weeks after I had returned to my situation two colored men informed me that a gentleman had been inquiring for a person whom, from the description, I knew to be myself, and offered them a considerable sum if they would disclose my place of abode; but they being much opposed to slavery, came and told me, upon which information I secreted myself till I could get off. I went into the Green mountains for several weeks, from thence to the city of New York, and remained in secret several days, till I heard of a ship, the "Napoleon", sailing to England, and on the 11th of November, 1835, I sailed, taking with me letters of recommendation to the Rev. Drs. Morison and Raffles, and the Rev. Alex. Fletcher. The time I first started from slavery was in July, 1834, so that I was nearly sixteen months in making my escape. On the 29th of November, 1835, I reached Liverpool, and my feelings when I first touched the shores of Britain were indescribable, and can only be properly understood by those who have escaped from the cruel bondage of slavery. When I reached Liverpool, I proceeded to Dr. Raffles, and handed my letters of recommendation to him. He received me very kindly, and introduced me to a member of his church, with whom I stayed the night. Here I met with the greatest attention and kindness. The next day, I went on to Manchester, where I met with many kind friends, among others Mr. Adshead, a hosier of that town, to whom I desire, through this medium, to return my most sincere thanks for the many great services which he rendered me, adding both to my spiritual and temporal comfort. I would not, however, forget to remember here, Mr. Leese, Mr. Childs, Mr. Crewdson, and Mr. Clare, the latter of whom gave me a letter to Mr. Scoble, the Secretary of the Anti-Slavery Society. I remained here several days, and then proceeded to London, December 12th, 1835, and immediately called on Mr. Scoble, to whom I delivered my letter; this gentleman procured me a lodging. I then lost no time in delivering my letters to Dr. Morison and the Rev. Alexander Fletcher, who received me with the greatest kindness, and shortly after this Dr. Morison sent my letter from New York, with another from himself, to the Patriot newspaper, in which he kindly implored the sympathy of the public in my behalf. The appeal was read by Mr. Christopherson, a member of Dr. Morison's church, of which gentleman I express but little of my feelings and gratitude, when I say that throughout he has been towards me a parent, and for whose tenderness and sympathy I desire ever to feel that attachment which I do not know how to express. I stayed at his house several weeks, being treated as one of the family. The appeal in the Patriot, referred to getting a suitable academy for me, which the Rev. Dr. Cox recommended at Hackney, where I remained half a year, going through the rudiments of an English education. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

0 Comments

Editor's note: The following excerpts are from "A Narrative of the Adventures and Escape of Moses Roper, from American Slavery" published 1838. Thank you to Contributing Scholar George A. Thompson for finding, cataloging and transcribing these excerpts. The language, spelling and grammar of the article reflects the time period when it was written. Learn more about Moses Roper here  Moses Roper (c. 1815 – April 15, 1891) was an African American abolitionist, author and orator. He wrote an influential narrative of his enslavement in the United States in his Narrative of the Adventures and Escape of Moses Roper from American Slavery and gave thousands of lectures in Great Britain and Ireland to inform the European public about the brutality of American slavery. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moses_Roper Fearing the "Fox" would not sail before I should be seized, I deserted her, and went on board a brig sailing to Providence, that was towed out by a steamboat, and got thirty miles from Savannah. During this time I endeavored to persuade the steward to take me as an assistant, and hoped to have accomplished my purpose; but the captain had observed me attentively, and thought I was a slave, he therefore ordered me, when the steamboat was sent back, to go on board her to Savannah, as the fine for taking a slave from that city to any of the free states is five hundred dollars. I reluctantly went back to Savannah, among slaveholders and slaves. My mind was in a sad state; and I was under strong temptation to throw myself into the river. I had deserted the schooner "Fox", and knew that the captain might put me into prison till the vessel was ready to sail; if this had happened, and my master had come to the jail in search of me, I must have gone back to slavery. But when I reached the docks at Savannah, the first person I met was the captain of the "Fox", looking for another steward in my place. He was a very kind man, belonging to the free states, and inquired if I would go back to his vessel. This usage was very different to what I expected, and I gladly accepted his offer. This captain did not know that I was a slave. In about two days we sailed from Savannah for New York. I am (August, 1834) unable to express the joy I now felt. I never was at sea before, and, after I had been out about an hour, was taken with sea-sickness, which continued five days. I was scarcely able to stand up, and one of the sailors was obliged to take my place. The captain was very kind to me all this time; but even after I recovered, I was not sufficiently well to do my duty properly, and could not give satisfaction to the sailors, who swore at me, and asked me why I shipped, as I was not used to the sea. We had a very quick passage; and in six days, after leaving Savannah, we were in the harbor at Staten Island, where the vessel was quarantined for two days, six miles from New York. The captain went to the city, but left me aboard with the sailors, who had most of them been brought up in the slaveholding states, and were very cruel One of the sailors was particularly angry with me because he had to perform the duties of my place; and while the captain was in the city, the sailors called me to the fore-hatch, where they said they would treat me. I went, and while I was talking, they threw a rope round my neck and nearly choked me. The blood streamed from my nose profusely. They also took up ropes with large knots, and knocked me over the head. They said I was a negro; they despised me; and I expected they would have thrown me into the water. When we arrived at the city these men, who had so ill treated me, ran away that they might escape the punishment which would otherwise have been inflicted on them. When I arrived in the city of New York, I thought I was free; but learned I was not, and could be taken there. I went out into the country several miles, and tried to get employment, but failed, as I had no recommendation. I then returned to New York; but finding the same difficulty there to get work, as in the country, I went back to the vessel, which was to sail eighty miles up the Hudson River, to Poughkeepsie. When I arrived, I obtained employment at an inn, and after I had been there about two days, was seized with the cholera, which was at that place. The complaint was, without doubt, brought on by my having subsisted on fruit only, for several days, while I was in the slave states. The landlord of the inn came to me when I was in bed, suffering violently from cholera, and told me he knew I had that complaint, and as it had never been in his house, I could not stop there any longer. No one would enter my room, except a young lady, who appeared very pious and amiable, and had visited persons with the cholera. She immediately procured me some medicine at her own expense and administered it herself; and, whilst I was groaning with agony, the landlord came up and ordered me out of the house directly. Most of the persons in Poughkeepsie had retired for the night, and I lay under a shed on some cotton bales. The medicine relieved me, having been given so promptly, and next morning I went from the shed and laid on the banks of the river below the city. Towards evening, I felt much better, and went on in a steamboat to the city of Albany, about eighty miles. When I reached there, I went into the country, and tried for three or four days to procure employment, but failed.. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Experiencing maritime travel during the reign of the steam engine in the Hudson River Valley was a vastly different experience for women than it was for men. Especially during the 1800s, it was quite rare to find both men and women traveling in the same spaces, such was the case in most forms of transportation, including steamboats on the Hudson River. The standard for the time was that men and women, when traveling, should be separate from each other. Matthew Wills on JSTOR Daily writes, “The Victorian segregation of men and women into separate spheres was quite rigorous in hotels, trains, and steamboats by the 1840s. Escorted and unattached ladies – ladies being very much a middle and upper class designation – were kept apart from unattached men (whatever their social status) via separate entrances, rooms, cars, and cabins.”[1] Mind you that the vast majority of these women traveling on steamboats on the Hudson River were of moderate to high wealth. To find steamboats or any other form of transportation without separate spaces for men and women was rare. It was very common to see women traveling with a suitable male escort, and rare to see women traveling without one. While women and men could meet each other in saloons and dining rooms, women would not permanently stay in these areas, and had access to their own separate space that only women could access. These separate spaces, at least on a Hudson River steamboat, were called “Ladies Cabins.” These spaces acted as their own separate saloon or parlor for women to relax and socialize with each other on journeys up and down the Hudson River, including everything women would need right down to their own bathroom facilities. Even the Rondout’s hometown steamboat, the Mary Powell, “Queen of the Hudson,'' had a ladies cabin. These ladies cabins would be managed by a female member of the steamboat’s crew. Such was the case with a Miss R. White, who was in charge of the ladies department on the steamboat L. Broadman.[2] Another example that depicts a woman being in charge of a ladies department of a steamboat is the story of the steamer Chief Justice Marshall. This unfortunately unnamed woman became a hero during a trip along the Hudson. The Newburgh Gazette reported on May 7th, 1830 that during a routine trip on the Hudson a boiler aboard the steamer Chief Justice Marshall exploded leading to boiling hot steam spreading across the ship. Immediately reacting, the unnamed woman quickly shut the door leading to the ladies cabin, and thoroughly secured it. This prevented the boiling hot steam from entering the cabin and scorching the women within the cabin alive.[3] While it is quite unfortunate that this woman was left unnamed, she is nevertheless responsible for saving the lives of all the women who were located in the ladies cabin of the steamer Chief Justice Marshall. Another woman that worked aboard a steamboat was Fannie M. Anthony, a stewardess aboard the famous steamer Mary Powell in its “ladies cabin.” As a woman of color, Fannie would clean and maintain the cabin, along with assisting passengers with requests. As a stewardess, her job would be similar to that of a housekeeper of a wealthy family. She would serve aboard the Mary Powell for decades before retiring in 1912. Interestingly, she was celebrated in local newspapers, uncommon at the time due to the fact that she was a woman of color, whose experiences are usually disregarded and forgotten throughout history. For example, an 1894 issue of the Brooklyn Times Union, quoting the Newburgh Sunday Telegram, celebrates Fannie Anthony in an article titled “Compliments for a Jamaica Woman.” It reads, “Mrs. Fannie Anthony, the efficient and obliging stewardess on the steamer Mary Powell, is about concluding her twenty-fifth season in that capacity. Mrs. Anthony enjoys an acquaintance among the ladies along the Hudson River that is both interesting and highly complementary to the amiable disposition and cheery manner of the only female among the crew of the favorite steamboat. Mrs. Anthony travels over 15,000 miles every summer while attending to her duties on the boat. She seldom misses a trip and looks the picture of health and happiness.”[4] You may notice that the article refers to Fannie as a Jamaican woman, they are not saying she is from the island of Jamaica in the Caribbean, she is actually from Jamaica, Queens in New York City. There are many other articles just like this one that reference Mrs. Fannie Anthony and talk about her in a positive way. While she was only a stewardess aboard the Mary Powell, it seems that through her enjoyable personality, the excellence of her service, and longevity in the time she served aboard the Mary Powell, she managed to overcome many of the immovable obstacles that faced most women of color at the time. Like the steamboat Mary Powell herself, Fannie achieved a measure of fame not usually afforded ordinary people, much less a woman of color. These three women all played vital roles in ensuring the successful, enjoyable, and safe travel of steamboats along the Hudson River. These women dedicated themselves to the people they served in their respective “ladies cabins.” In the case of Miss R. White and Mrs. Fannie Anthony, that was to serve their passengers with distinction and dignity. In the case of that unfortunately unnamed woman who worked in the “ladies cabin” of the steamer Chief Justice Marshall, she was a hero who saved the lives of everyone in the ladies cabin from being boiled alive from the steam that escaped the engines of that steamer. [1] Wills, Matthew. Separate Spheres On Narrow Boats: Victorians At Sea. Jstor Daily, November 22, 2021. https://daily.jstor.org/separate-spheres-on-narrow-boats-victorians-at-sea/ [2] Rockland County Messenger. Welcome Steamer L. Boardman. Haverstraw, New York. March 21, 1878. 1878-03-21 [3] The Newburgh Gazette. 1830-05-07 [4]https://omeka2.hrvh.org/exhibits/show/mary-powell/staffing-the-mary-powell/african-americans/fannie-m--anthony AuthorJack Loesch is a senior at SUNY New Paltz majoring in the field of History, with a minor in If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's Note: The following report of the Eastern New York Anti-Slavery Society was found by HRMM research George A. Thompson and transcribed by Sarah Wassberg Johnson. The Eastern New York Anti-Slavery society was based in Albany, NY and founded by Reverend Abel Brown in 1842. Although less well-known than the Western New York Anti-Slavery Society, which counted Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth among its members, the Eastern New York Anti-Slavery Society nevertheless did important work with the Underground Railroad. Resources for further reading on this subject are located at the bottom of this post. EASTERN N.Y. A. S. SOC. & FUGITIVE SLAVES. ANNUAL REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE. [1843] In a previous Report of the Committee engaged in aiding fugitive slaves, they endeavored to show the propriety and duty of progressing in this work of mercy and benevolence. Another year has passed, and in the light of its experience the Committee have found additional proofs of the importance of this object, and for still more active zeal in the prosecution of their labors. They have ever deemed it essential that a systemic plan of operations should be sustained for the permanent security and protection of those down trodden outcasts of humanity. Among the many reasons considered by them for engaging in this work of benevolent enterprise, the following presents themselves: 1st. The aiding away of fugitive slaves is producing a beneficial effect on the slaveholder. There are in this nation from 200,000 to 300,000 men who are laboring under an alienation or infatuation of mind which leads them to persist in robbing their fellow men of their dearest rights. They are truly led captive by the devil, at his will, for they not only engage in deeds at which humanity shudders, and which God abhors, but are so perfectly and madly insane that they glory in saying and believing that they understand and correctly appreciate the true principles of our moral, religious and political institutions, that they only in all this generation worship God in spirit and in truth. They steal, lie, blaspheme, rob, murder, commit whoredom -- yes, crimes of which it is even a shame [illegible line] have been stolen and now hold and rob the colored people in this nation. They hold their so called property as any other thief holds his stolen goods, and it is as much the duty of honest men to seize these human goods and restore them to their rightful owners whenever opportunity presents, as to aid in restoring any other stolen property. When a man thief loses the property he has stolen, it affects him in the same manner as thieves in general. A moment’s reflection will illustrate. Suppose a man steals $1000 in cash, and after a few months enjoyment of it, the rightful owner by some artful device gets possession of it - what would be the effect of the loss of the unlawful inheritance upon the mind of the thief? - Would he not be more apt to reflect upon the wickedness of the crime he had committed? Would he be as apt to steal again? And would not the effect upon the man who has stolen $1000 worth of human beings be similar? Certainly no one would for a moment suppose that it is less a criminal offence to steal men than money. A member of the committee lately received a letter from a friend who resides in the family one of those unfortunate men who has lost his slaves. A slave by the name Robert was missing. There were frequent conversations in the family about Robert. The mistress frequently expressed her fears that the servant was suffering in the swamps, and perhaps dying of starvation. The children cried because Robert was gone, while the father swore he would thrash the rascal if he ever caught him. Weeks, and even months elapsed, but no news from Robert. The master had given him up for lost, not only to his owner but also to himself, for it was not possible that he could take care of himself. At length during a pleasant evening, as the family were quietly enjoying themselves in the parlor, a letter was handed in addressed to the master in quite a neat and respectable hand writing. - He opened and after looking a moment, exclaimed in surprise, it is from Robert. He informed his master that he had safely arrived in Canada and found himself very happy - was quite pleasantly situated; thanked his master and the family for all their kindness; spoke of his mistress with great respect for her kindness; sent his kindest regards to all and especially his dearest love to the children, and closed by earnestly urging hist master to call and “take-tea” with him, should he ever pass that way. The effect of the unexpected letter upon the family was electrifying. The children were enthusiastic in their expressions of joy - Robert alive, Robert well, Robert free; I wish I could see him; I wish he would come back. The mother of the family wept. She had often expressed her fears that Robert was suffering in the forests or swamps, and the letter seemed to relieve her; she only said “poor fellow, I am glad he has got to Canada.” A son of about twenty years said “I should like to lick the scoundrel an hour.” The master was evidently much chagrined but sat in silence and heard the rejoicing of the children and saw the tears of his wife, finally he said, “I did not think the fellow knew so much.” “I did not mistrust he would run away, but I would have done just so too.” The conversations about the runaway were frequent, and although the master was evidently enraged and chagrined at the loss of Robert, yet the effect upon him was quite salvatory. He was afflicted with his situation. Mad alike with slavery and abolition, and in a right state of mind to accept of emancipation or any thing that would free him from the curse of slavery. He did not buy other servants to fill the place of his most faithful Robert, but contented himself to hire what was necessary to make up the deficiency of labor. One man in Baltimore has lost six slaves five of whom were aided by the Albany Committee, and such has been the beneficial effect on the afflicted man that he has since that time hired his servants. Indeed, the loss of servants has become so frequent that very few persons in towns and cities as far north as Washington buy slaves for their own use. $1000 worth of property on feet is not as valuable as formerly, and such investments are not deemed very safe, and the committee are happy to know that slave stocks are depreciating in value daily. The numerous Judicial trials which have been brought to notice by the efforts of the committee have been instrumental in teaching slaveholders that they cannot much longer make New York their hunting ground. Indeed they are sorely afflicted by these lawsuits, for they cost them a large amount of money, and after all have the honor and satisfaction of getting beat in every case. The Corresponding Secretary of the Committee has received numerous letters from southern men, which indicate that they are far from being uninfluenced by our efforts. Many of these letters are too vulgar and blasphemous for publication. Although evidently written by men of intelligence, they exhibit a corruption of heart that is indescribable. In June last a most obscene and wicked letter was received enclosing two handbills of which the following is one: - [end of page] Sadly, the second page was not included in this find. Although some of this text may seem distasteful today, it was part of an effort to convince Whites of the value of abolishing slavery. The passage about the contrite family of enslavers was especially designed to tug at the heartstrings and engage guilty consciences. In addition, the last selection indicated (accurately or not) that anti-slavery efforts were having some affect even among those who profited from enslaving others. The reference to New York as a "hunting ground" is referring to the Fugitive Slave Act, which allowed Southern slaveholders to send "slave catchers" north to recapture people who had escaped slavery. Sadly, many free people were captured and sold into slavery, as was the case with Solomon Northup. Reverend Abel Brown died tragically young, at the age of 34, in 1844, just one year after this report. His widow would go on to write his memoir (linked below). Further Reading:

If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's note: The following articles were originally published in the New-York Evening Post and the New-York Daily Advertiser in June 1817. Thanks to volunteer researcher George A. Thompson for finding, cataloging and transcribing this article. The language of the articles reflect the time period when it was written. For more information see Dr. Jonathan Daniel Wells' presentation for the HRMM lecture series, of his book "The Kidnapping Club: Wall Street, Slavery, and Resistance on the Eve of the Civil War" here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=chjcZEQR9iY KIDNAPPING -- This most odious, and I might even say, worst of crimes, which has hitherto been principally confined to the southern states, has of late found its way among us. On Thursday last, information was lodged with the Manumission Society, that a gang of scoundrels were engaged in seducing, and decoying free men of color, on board a small schooner, called the Creole, then lying up the North River, a little distance above the state-prison, with the intention of transporting them abroad and selling them as slaves for life. Assistance was procured from the police-office, the schooner boarded, and a search took place, when behold, on opening the hatches, 9 poor unfortunate sons of Africa, who were huddled together in her hold, half suffocated, leaped upon deck, and disclosed to their deliverers the scene of villainy which had been practiced upon them. One of the owners of the schooner, James H. Thompson, who belongs to Virginia, attempted to make his escape in the long-boat, but was overtaken, secured, and together with the people of colour were taken to the police-office. Upon examination it appeared that one Moses Nichols, who keeps a brothel in Love-lane, in the vicinity of this city, and one Royal Bowen, were accomplices of Thompson in his odious traffic in human flesh. They have likewise been taken into custody and all three sent to Bridewell. The following are the names of the blacks who were kidnapped: -- Stephen aged 12, Jacob aged 19, Hannah aged 23, Mink aged 18, Mary aged 8, Harvey aged 10, Henry James aged 20, Caty aged 20 and Ann Freedland. Two of the above were brought from Albany, six from Poughkeepsie, and one belonged to this city. Various were the strategems used to deceive these poor ignorant creatures, and keep them in the dark as to the hard fate which awaited them. At one time they were told that they would be employed as gentlemen’s servants; at others they were to be hostlers. They were conveyed to the schooner in a coach last Thursday afternoon, in a violent rainstorm, and soon after put under hatches, and would, in all probability, have been taken to sea that night, had not the authority interposed. One of the colored women was brought to this city in a sloop from Poughkeepsie, by one of the above named fellows, (Nichols,) who pretended to be her master, and during the whole passage was observed to read frequently in the bible, and at other times to weep, and refuse all sustenance offered her. On the captain of the sloop inquiring of her the cause, she told him she was apprehensive that there was a scheme on foot to transport her out of the country. Thompson, the principal actor in this disgraceful traffic [had claimed last winter to have been] knocked down in Warren street and robbed of a large sum of money. We understand from the police officers he is an old offender, and was concerned with a couple of fellows who were indicted last winter for kidnapping. It would, perhaps, be no more than fair to state, that the captain of the schooner, who was supposed to be implicated, has been examined and discharged. It is therefore presumable that he had no knowledge of the nature of the voyage he was about to enter upon. - New-York Daily Advertiser, June 30, 1817 KIDNAPPERS TAKEN. It gives great pleasure to state that a number of villains, engaged in the atrocious crime of kidnapping people of colour, have lately been discovered in this city, through the benevolent exertions of Mr. S. Kelly, of Poughkeepsie, who suspecting the plot, came to this city on Thursday last, and communicated the intelligence to the Manumission Society. Immediate measures were taken to secure them and rescue the unfortunate victims that had fallen into their clutches. The principal of the gang is a man calling himself James H. Thompson, who last fall purchased some slaves of a Captain Storer, who sailed from this port in a vessel called the Alligator, with four blacks on board kidnapped here, touched at Philadelphia and procured two more, and then proceeded to Baltimore, where they were sold. Thompson undertook to convey them to Georgia, but in passing through North Carolina, the blacks procured an opportunity to communicate their situation to some travellers, who interceded on their behalf. On reaching the town of Winton, Thompson was seized, and bound to appear at Court. Having got bail, he came on to this city, for the purpose of procuring testimony concerning his slaves. During the winter, he was knocked down in Warren-street, by Arthur Miles, Captain Storer's mate, and robbed, as he stated, of rising one thousand dollars. After this he went back to Georgia, where he resides, being, according to his own story, a farmer in King's county, and has a family of seven children. Some time ago, he took passage in a vessel at Savannah, & came to this city, accompanied by a fellow who calls his name Crabtree. Here the nefarious combination was formed. Their head quarters was at a notorious gambling house, occupied by Moses Nichols, in Love‑Lane, a road but little travelled, about two and a half miles from the city. Nichols was supplied with funds, and sent out on a Northern tour -- at Albany he procured two, and at Poughkeepsie six blacks, pretending he purchased them for his own use, and had them conveyed to his brothel, where they were kept secure by the rest of the gang. While Nichols was busy to the North, Thompson, Crabtree and others were to work here. In the whole ten blacks had fallen into their hands, This being a tolerable cargo, and delays dangerous, they were preparing to depart with their booty, and would no doubt have left this port on Friday last, had not a discovery taken place. On Thursday, the standing committee of the Manumission Society watched their manouvres. In the night, while the rain fell in torrents, the blacks were conveyed in a carriage by Thompson, from the house of Nichols, and put on board a small schooner called the Creole of New‑York, then lying in the North River, about a half a mile above Fort Gansevoort. On Friday morning, information was given to the Police, who promptly afforded assistance. The vessel was boarded, and eight blacks found on board, secured in the hold and cabin. On enquiry of Thompson, who appeared as the owner of the vessel, he stated that two of the blacks were his own property, the rest were passengers, put on board by Nichols, who were to be landed at Poughkeepsie and Albany, where the vessel was bound for a load of cheese, and from thence to Baltimore. The schooner was seized by the Custom House Officer, and Thompson and his accomplices conveyed to Bridewell. On Saturday Thompson was brought before the Police for examination -- in the course of his evidence he stated he had purchased the schooner for coasting, and that the blacks were bought for his relations in Baltimore. He denied having any connexion with Nichols, and pretended he knew no such man as Crabtree, but being more closely questioned, acknowledged they came passengers together from Savannah. After his affidavit was drawn up, it was handed him to read, and notwithstanding he stated it to be correct, refused to sign it. The following is Mr. Stilwell's affidavit, who was employed to navigate the vessel, but who it appears had no knowledge of the villainy going on. He was accordingly discharged. CITY OF NEW-YORK, ss. William Stilwell of No. 22 Hester-street, being duly sworn, says that eight or ten days since he was employed by James H. Thompson, the man now here, to act as captain of the vessel called “The Creole of New-York” -- That deponent obtained coasting licence, and was to sail yesterday to a place called Darien, [Georgia] about 60 or 70 miles from Savannah, in South Carolina* -- that said Thompson said that he was to take nothing but passengers out, together with a few blacks, their servants, and he was to return to this port with a cargo of wheat. WM. STILLWELL. Sworn the 27th day of June, 1817. J. HEDDEN, Police Justice. When this villainous conspiracy shall have undergone a full examination, we have no doubt other actors will be discovered, and that it will be found to have consisted of a gang of BLOODY THIEVES who have long been engaged in kidnapping this unfortunate race of people. We thank God that through the exertions of the friends of Africans, they have at length been taken, and are about to suffer the just sentence of the law for their atrocious crimes. Names of the blacks and their ages -- Stephen aged 12, Jacob 19, Hannah 23, Mink 18, Harvey 10, Henry James 20, Caty 20, Jane Freedland, and one other. New‑York Daily Advertiser, June 30, 1817. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Crew of the steamboat Mary Powell posing on deck. 1st row: Fannie Anthony stewardess; 4th from left, Pilot Hiram Briggs; 5th, Capt. A.Eltinge Anderson (with paper); 6th Purser Joseph Reynolds, Jr. Standing 3rd from left: Barber(with bow tie). Other crew members unidentified. Donald C. Ringwald Collection, Hudson River Maritime Museum. The Mary Powell was one of the longest-serving and most famous of the Hudson River passenger steamboats. She was in operation from 1861 to 1917, and many of her crew were Black and African American. Although it is not clear whether or not Black or African American passengers were allowed to travel aboard the Mary Powell, many of them did work aboard the boat, mostly restricted to lower-paying jobs such as deckhands, waiters, and boilermen. Some steamboats did have Black stewards, and the Mary Powell had Fannie M. Anthony – the Black stewardess who managed the ladies’ cabin for decades, but it is unclear if any of the stewards listed in the Mary Powell crew records were African American or not. However, there were enough Black employees working aboard the Mary Powell for them to form their own club - The Mary Powell Colored Employees Club. The little evidence we have of the Mary Powell Colored Employees Club comes from newspaper articles, primarily organized around the annual cake walk the club put on each year between at 1909 and 1917. Cake walks were a style of dance popular in the 1890s and 1900s among Black communities, and often co-opted by Whites. Originating in enslaved communities as a mockery of the formal dances, primarily the Grand March, of Southern plantation owners, athletic variations invented by African and African-American dancers lent themselves well to competitions. Cake walks generally had two variations – graceful and athletic versions designed for Black audiences, and wild caricatures designed for White audiences, often in conjunction with minstrel shows. These two historic films illustrate the differences. The first shows Black dancers in formalwear, focused on elegance. The second features those same dancers in exaggerated dress, performing a comedic routine, likely for a White audience. In 1909, the Kingston Daily Freeman announced the first annual cake walk of the “colored employees of the steamer Mary Powell.” About a month later, on September 23, the Freeman reported on the success of the cakewalk. Held at Michel’s Hall (located at 53 Broadway), “The hall was filled with friends of the Powell’s colored employes [sic], besides many others composing the officers and crew of the boat.” This mention of other officers and crew seems to imply that the event may have been integrated. The article also lists the officers of the Mary Powell Colored Employees Club:

Prizes were offered for the best dancers, and first prize went to John Schoonmaker of Kingston, NY and Medina Schoonmaker of Poughkeepsie, NY. “Second honors were taken by Ott Overt and Maude Overt of Poughkeepsie.” The Poughkeepsie Evening Gazette also reported on the cake walk, likely because residents of that city placed in the contest. The cake walk continued in 1910, held on September 15, again at Michel’s Hall. This time the walk featured Professor Butler’s orchestra from New York City, as well as “several professional cake walkers from New York, Newburgh and Poughkeepsie.” No articles appear for the 1911 dance, but in October of 1912 something curious happened – two different dances for Mary Powell employees occurred, just days apart. On October 2, 1912, the Mary Powell Colored Employees Club held their “fourth annual ball and cake walk” at Michel’s Hall, with Professor Butler’s orchestra and “two couples of professional cake walkers.” But on October 3, 1912, the Kingston Daily Freeman announced “The first annual dance of the deck hands of the Mary Powell will be held in Washington Hall on Saturday evening.” On the appointed day, October 5, the Freeman reported: “The Mary Powell deck hands will hold their annual dance in Washington Hall this evening. This dance has always been one of the most popular of the season and it is expected that this year will be no exception.” Were these the same dance? Likely not – one took place on October 2nd in Michel Hall, located at 53 Broadway in Kingston. The other took place on October 5th in Washington Hall, located at 110 Abeel Street in Kingston. Was one a dance for the Black employees and the other a dance for White employees? Did the person writing the October 5th article confuse the deck hands’ dance with the Mary Powell Colored Employees Club dance? Or did the deck hands really have dances before 1912? It seems likely that 1912 was the first year of the deck hands’ dance, corroborated by an advertising poster from 1912 confirming that as the first year. Notably, future Mary Powell captain Arthur Warrington is listed as the President of the Mary Powell Deck Hands. Lawrence Dempskie is listed as Vice-President, John Malia as Treasurer, Frank Sass as Secretary, and George Brown as chair of the Floor Committee. Note also the reduced price for ladies. There is almost no further mention of either club or dance, except for one reference in the New York Age, a Black newspaper based in New York City. On September 20, 1917, the reported, “The annual dance given September 12 by the young men of the steamer Mary Powell was largely attended. Good music contributed to an enjoyable evening. Many from out of town attended.” This is almost certainly referencing the Mary Powell Colored Employees Club event. 1917 was the last season of the Mary Powell – she remained out of service in 1918 and was sold for scrap in 1919. To learn more about Black and African American workers aboard the Mary Powell, check out our previous blog posts on Fannie M. Anthony, the Black Glee Clubs of the Steamboats Mary Powell and Thomas Cornell, and check out our online exhibit about the Mary Powell. For more information about Black history on the Hudson River and in the Hudson Valley, check out our Black History blog category for more to read. AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson is the Director of Exhibits & Outreach at the Hudson River Maritime Museum. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

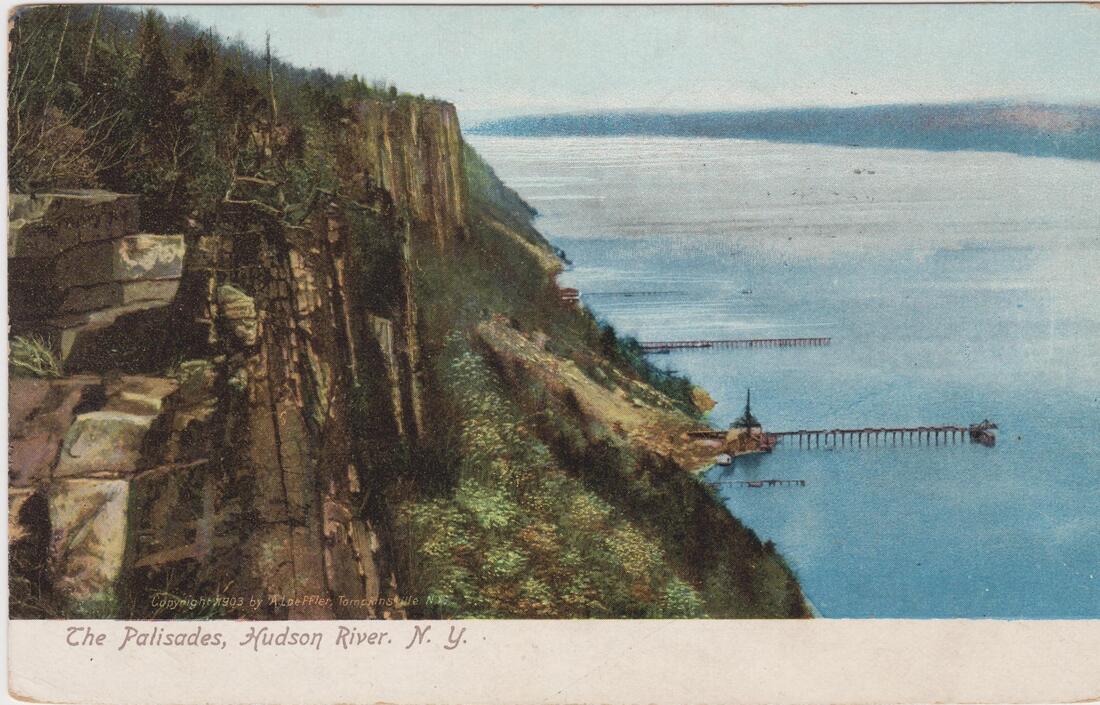

Tonight the museum will welcome Wes and Barbara Gottlock to discuss their book Lost Amusement Parks of the Hudson Valley as part of the Follow the River Lecture Series. So we thought we'd revisit some of the stories of amusement parks and steamboat landings on the Hudson River we've already published here on the History Blog. Follow the links in the introductions below to read more about each park.  Postcard of Kingston Point Park, featuring the island bandstand and rental boats. Hudson River Maritime Museum Collection. Postcard of Kingston Point Park, featuring the island bandstand and rental boats. Hudson River Maritime Museum Collection. Kingston Point Park Kingston's own local amusement park, Kingston Point Park was built by Samuel Coykendall, owner of the Cornell Steamboat Company and Ulster & Delaware Railroad. It featured a merry-go-round with a barrel piano (which is now in the museum) along with walking paths, a Ferris wheel, boat rentals, and other attractions. The main point was to serve as a landing for the Hudson River Day Line, and trains and trolleys would whisk passengers to Kingston and the Catskills. Kingston Point Park also featured prominently in 4th of July celebrations in the past.  Hudson River Day Line steamer "De Witt Clinton" approaching Indian Point Park in foreground, circa 1923. From the Donald C. Ringwald Collection, Hudson River Maritime Museum. Hudson River Day Line steamer "De Witt Clinton" approaching Indian Point Park in foreground, circa 1923. From the Donald C. Ringwald Collection, Hudson River Maritime Museum. Indian Point Park Formerly a farm, Indian Point Park was purchased specifically as a destination park for the Hudson River Day Line to rival that of Bear Mountain. It was later converted into a nuclear power plant.  Postcard of steamboat docks at the Palisades, Hudson River Maritime Museum Collection. Postcard of steamboat docks at the Palisades, Hudson River Maritime Museum Collection. Palisades Interstate Park The creation of the Palisades Interstate Park was due in large part to the work of women. The Palisades had long been a major landmark for any Hudson River mariner. Elevators were used in the late 19th century to get visitors from their steamboats at water level up to the park on top of the cliffs. Escaping Racism Amusement parks and picnic groves on the Hudson River could also be an escape. So in honor of Black History Month, we're re-sharing this wonderful article on how Black New Yorkers used steamboat charters to area parks to escape the prejudice and racism of the 1870s. Lost Amusement Parks of the Hudson Valley There's still time to join us for tonight's lecture! Register now. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's Note: The following text is a verbatim transcription of an article written by George W. Murdock, for the Kingston (NY) Daily Freeman newspaper in the 1930s. Murdock, a veteran marine engineer, wrote a regular column. Articles transcribed by HRMM volunteer Adam Kaplan. It was 2 o’clock in the morning, just 63 years ago today, December 1, 1875, that the magnificent steamboat “Sunnyside” met her fate. This memorable early morning disaster which claimed many lives, still remains a vivid picture in the memory of George W. Murdock, who was a member of the crew of the ill-fated vessel. The wooden hull of the “Sunnyside” was built by C.R. Poillon of Williamsburg, New York, in 1866. The vessel was 247 feet, six inches long, with a 35 foot, four inch breadth of beam. She was rated at 942 gross tons and was powered by an engine with a cylinder diameter of 56 inches with a 12 foot stroke, built by S. Secor & Company of New York. The “Sunnyside” and “Sleepy Hollow” were sister steamboats, built for service on the lower Hudson river, running in passenger service between Sing Sing and New York. Both vessels were fine examples of modern steamboat construction of that period and both were possessed of good speed. They began operating in the spring of 1866, making landings at Yonkers, Irvington, and Tarrytown, with one vessel and covering the identical route but extending to Grassy Point with the other vessel. This double service continued until July of the following year (1867), when the “Sunnyside” was placed in operation running to Newburgh for the balance of the season, and was then laid up. In July, 1870, Joseph Cornell in partnership with Captain Black, bought the “Sunnyside” at auction for $45,000. She was then converted into a night boat and placed on the Coxsackie route, continuing in service on this route for the balance of that season and through the year 1871. She made a landing at Catskill on alternate days with the “Thomas Powell,” which plied the Hudson river only as far as Catskill. During the winter of 1871-1872, Joseph Cornell, George Horton and Thomas Abrams organized the Citizens’ Line, placing the “Sunnyside” and “Thomas Powell” in service in opposition to J.W. Hancox, who was operating the “C. Vanderbilt” and the “Connecticut.” In July, 1872, the Hancox steamboats were withdrawn and the Citizens’ Line was without opposition. The “Sunnyside” was one of the fastest night boats carrying staterooms on the Hudson river during that period, and in July, 1874, she made the run from New York to Troy in eight hours and 55 minutes. The hand of fate seemed to hover over the “Sunnyside” almost from the time she first slid into the waters of the Hudson river. She met with numerous accidents during her career, some of little consequence, while others caused damage to the vessel and claimed lives of some unfortunates. One night, on her down trip from Troy, in the latter part of May, 1874, the “Sunnyside” collided with the abutment of the Congress street bridge at Troy, staving in her starboard boiler which was located on her guards. The escaping steam caused the death of one man. In November of the same year she ran aground on Fish-house bar between Troy and Albany, striking with such force that she stove a hole in her hull and almost sunk. During the month of August 1875, she caught fire from spontaneous combustion in some bales of cotton on her main deck, but the flames were discovered in ample time to avert serious damage. On Tuesday afternoon at 2 o’clock on November 30, 1875, the “Sunnyside” left Troy for her last trip of the season, and what later proved to be the final sailing of her career. The following account is told by George W. Murdock, a member of the crew on this last trip, who was an eye-witness to the fateful voyage and who narrowly escaped the clutching fingers of death which claimed many victims in that early morning catastrophe. We left New York Monday, November 29, and headed up river with a heavy cargo of freight. The thermometer in New York registered from 40 to 45 degrees above zero at the time we left the dock. Coming up the river, the temperature rapidly changed, becoming much colder until at Kingston we began pushing our way through thin ice. We arrived at Troy at 8 o’clock Tuesday morning, November 30, with the thermometer registering zero. Unloading was accomplished as quickly as possible with the temperature hovering at zero throughout the day. On reaching Albany we took the steamboat “Golden Gate” in tow to follow us down the river. We broke through the drift ice from Troy to Kinderhook, there encountering solid ice. The steamboat “Niagara,” with a tow of canal boats and several schooners, lay ice-bound at this place. We left the “Golden Gate” also ice-bound, and backed and filled several times, breaking a course through the ice and relieving the ice-bound fleet; after which we proceeded down the river. At Barrytown it was discovered that our vessel was leaking, and the pumps were started. At Esopus Island we ran through clear water which washed away the fine ice which had formed about the hole which had been made on the port side when we had crashed through the ice at Kinderhook. We were off West Park and endeavored to make shore at Russell’s dock as we were leaking badly by this time. The “Sunnyside” went through thick ice on the west bank of the river, but slid back into deep water. The flood time swung the bow of the vessel up the river until the pilot house was filled with water, and all that remained out of water was about 40 feet of the hurricane deck, aft. This was 2 o’clock in the morning and the weather was bitter cold, the thermometer registering five below zero. Captain Teson, in charge of the “Sunnyside,” ordered the boats to be lowered, sending Mate Burhonce in charge of the first one. It capsized, drowning 11 out of 18 passengers and crew. The mate swam ashore. We then succeeded in getting a line ashore from the steamboat and so established a rope ferry. It was now 5 o’clock in the morning. In this fashion we pulled the life boat through the ice and the passengers and crew of the ill-fated steamboat were landed on snow-covered shore of Ulster county. They climbed the rocks along the shore and made their way to the farm houses in the vicinity where every attention possible was given them, but several died from the results of too long exposure. Among those lost were Sarah Butler and Susan Rex (colored), of New York, chambermaids; John Howard (colored), of New York, officers’ waiter; Samuel Puteage (colored), waiter, of New York; Matthew Johnson (colored), of Albany; George Green (colored), second cook, of Norwich, Connecticut; Mrs. Haywood of Tenafly, N.J., Mrs. Stewart of New York, Mrs. Walker of Troy, an Irish girl called Bridget, resident of Jersey City; and an unknown peddler of silks and jewelry. At the request of my uncle, Abram Parsell, of Port Ewen, who was chief engineer on the “Sunnyside,” I set out afoot for Port Ewen at 6 o’clock on that bleak morning of December 1, to break the news of the disaster to his wife and the people of the town. At that time the thermometer had gone down to six degrees below zero and hiking that distance of about 10 miles was rather a task. Stories of the tragic accident had already arrived at Port Ewen so my news that my uncle was safe was joyously received by his many friends in the town. The crew of the “Sunnyside” were: Captain Frank Teson of Lansingburg; first pilot, Robert Whittaker of Saugerties; second pilot, Watson Dutcher of New York; mate, Jacob Burhonce of Troy; chief engineer, Abram Parsell of Port Ewen; assistant engineer, Jerry Deyo of Port Ewen; purser, John Talmadge of New Baltimore; steward, George Wolcott of New York; freight clerk, Edward Johnson of Troy. The “Sunnyside” was raised and her hull broken up, while her engines were placed in the steamboat “Saratoga.” AuthorGeorge W. Murdock, (b. 1853-d. 1940) was a veteran marine engineer who served on the steamboats "Utica", "Sunnyside", "City of Troy", and "Mary Powell". He also helped dismantle engines in scrapped steamboats in the winter months and later in his career worked as an engineer at the brickyards in Port Ewen. In 1883 he moved to Brooklyn, NY and operated several private yachts. He ended his career working in power houses in the outer boroughs of New York City. His mother Catherine Murdock was the keeper of the Rondout Lighthouse for 50 years. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Saturday was the Conference on Black History in the Hudson Valley, so for today's blog post we thought we'd share this brief overview of Slavery in the Hudson Valley from Vassar College. It's a common misconception that the North did not have slavery. New York was one of the largest slaveholding colonies in the 18th century. The conference presentations were recorded and will be available on YouTube in the coming weeks. Subscribe to our YouTube channel to ensure you don't miss a video. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

This coming Saturday is the Conference on Black History in the Hudson Valley, so we thought this Media Monday that we would share this award-winning documentary film. Completed in 2018, "Where Slavery Died Hard: The Forgotten History of Ulster County and the Shawangunk Mountain Region" is the creation of the Cragsmoor Historical Society and was co-authored by archaeologists Wendy E. Harris and Arnold Pickman. It is a common misconception that slavery did not exist in the North, or if it did, it "wasn't as bad" as in the South. This is false. New Amsterdam had enslaved people since the beginning, as slavery was a cornerstone of much of Dutch colonialism. And in the mid-18th century, more New Yorkers enslaved people than almost any other American colony. New York was one of the last Northern states to abolish slavery (New Jersey had "apprenticeships" until 1865). New York City was staunchly pro-slavery, even during the Civil War, but upstate New York was a hotbed of abolitionist activity, from Western New York to Albany. "Where Slavery Died Hard" chronicles the role of slavery in Ulster County, including the story of Sojourner Truth, who was enslaved in Port Ewen (just across Rondout Creek from the Hudson River Maritime Museum) and elsewhere in Ulster County. If you'd like to learn more about Black History in the Hudson Valley, you can attend the conference (in-person and virtual options available!), check out our past Black history blog posts, or visit the Hudson Valley Black History Collaborative Research Project and its in-process collection of Black history resources and research specific to the Hudson Valley. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

|

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 [email protected] Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |