History Blog

|

|

|

|

|

Welcome to Sail Freighter Fridays! This article is part of a series linked to our new exhibit: "A New Age Of Sail: The History And Future Of Sail Freight In The Hudson Valley," and tells the stories of sailing cargo ships both modern and historical, on the Hudson River and around the world. Anyone interested in how to support Sail Freight should also check out the Conference in November, and the International Windship Association's Decade of Wind Propulsion. The West Country Ketch Hobah was an English vessel built in 1879, and is typical of her class: Ketch rigged, relatively small at around 80 feet and 60 Net Register Tons, and built with a wide flat bottom, she was designed for use in the South of England. She served as late as 1945, moving coal, general cargo, manure, and stone. The ketch's wide, flat bottom allowed for loading and unloading from beaches where no developed port was available, a common practice with small vessels. The photo above shows this process in action, with the Ketch tied up to the stake on the left, the tide was allowed to recede, while the ship settles into the sand and stays stable while discharging cargo. When high tide returns, the lines can be cast and the ship sails away unharmed. While very typical of her class, the Hobah's career is especially long, spanning 66 years. She was engaged on trade routes which were fully developed by the 17th century, and active through the early 20th. Those routes have been mapped by Oliver Dunn and a team of historians, and span the entirety of the British coast. Like many other late sail freighters, she carried mostly bulk cargos around areas with underdeveloped land transportation networks before the introduction of fossil-fueled trucks, and was quite successful. AuthorSteven Woods is the Solaris and Education coordinator at HRMM. He earned his Master's degree in Resilient and Sustainable Communities at Prescott College, and wrote his thesis on the revival of Sail Freight for supplying the New York Metro Area's food needs. Steven has worked in Museums for over 20 years. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

0 Comments

There's been a lot of talk around our new exhibit about the decline and revival of working sail, but most of it has been rather serious or technical. This isn't, at all, in any way. I first became aware of this tune through my Dad, who was in the Navy and sang with several choirs while he was in. It's a classic example of mild sarcasm to deal with the changing of the times and the decline of sail, as well as other technical changes which occurred quite rapidly over the 20th century. The song comically laments changes and the now-pointless nicknames of some jobs, such as Bunting-Tossers (signalers), Stokers (engineers), and the change from hammocks to bunks. This is also a song that has seen some significant revival recently, being recorded in several styles, of which these two are just a sampling. David Coffin is an old hand in the nautical and folk music scene, but Nathan Evans is a relatively new Scottish pop-folk sensation. This broadening of audiences helps spread and preserve these songs as a living and changing tradition, as they have been for thousands of years. So, sit back and enjoy the sounds of a satirical farewell to the first age of sail, and an ode to the harder, harsher, near-unsurvivable, tough old days of the "Real Navy" only remembered by Senior Chief Petty Officers who are nearing retirement. LYRICS (From David Coffin's version): Well my father often told me when I was just a lad A sailor's life is very hard, the food is always bad But now I've joined the navy, I'm aboard a man-o-war And now I've found a sailor ain't a sailor any more Don't haul on the rope, don't climb up the mast If you see a sailing ship it might be your last Just get your civvies ready for another run ashore A sailor ain't a sailor, ain't a sailor anymore Well the killick of our mess he says we had it soft It wasn't like that in his day when we were up aloft We like our bunks and sleeping bags, but what's a hammock for? Swinging from the deckhead, or lying on the floor? Don't haul on the rope, don't climb up the mast If you see a sailing ship it might be your last Just get your civvies ready for another run ashore A sailor ain't a sailor, ain't a sailor anymore They gave us an engine that first went up and down Then with more technology the engine went around We know our steam and diesels but what's a mainyard for? A stoker ain't a stoker with a shovel anymore Don't haul on the rope, don't climb up the mast If you see a sailing ship it might be your last Just get your civvies ready for another run ashore A sailor ain't a sailor, ain't a sailor anymore They gave us an Aldiss Lamp so we could do it right They gave us a radio, we signaled day and night We know our codes and ciphers but what's a sema for? A bunting-tosser doesn't toss the bunting anymore Don't haul on the rope, don't climb up the mast If you see a sailing ship it might be your last Just get your civvies ready for another run ashore A sailor ain't a sailor, ain't a sailor anymore Two cans of beer a day and that's your bleeding lot And now we've got an extra one because they stopped The Tot So we'll put on our civvy-clothes find a pub ashore A sailor's still a sailor just like he was before Don't haul on the rope, don't climb up the mast If you see a sailing ship it might be your last Just get your civvies ready for another run ashore A sailor ain't a sailor, ain't a sailor anymore AuthorSteven Woods is the Solaris and Education coordinator at HRMM. He earned his Master's degree in Resilient and Sustainable Communities at Prescott College, and wrote his thesis on the revival of Sail Freight for supplying the New York Metro Area's food needs. Steven has worked in Museums for over 20 years. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Welcome to Sail Freighter Fridays! This article is part of a series linked to our new exhibit: "A New Age Of Sail: The History And Future Of Sail Freight In The Hudson Valley," and tells the stories of sailing cargo ships both modern and historical, on the Hudson River and around the world. Anyone interested in how to support Sail Freight should also check out the Conference in November, and the International Windship Association's Decade of Wind Propulsion. Today's Windjammer is the Preussen, the only five-masted full rigged cargo ship ever built, and the largest of the early 20th century windjammers. 482 feet long and carrying up to 8,000 tons of Nitrates from Chile to Germany per voyage, she was designed to round Cape Horn and return at great speed, making up to 20.5 knots under up to 73,000 square feet of sails. She was the pinnacle of the sailing vessel, and was in service for 8 years carrying nitrates and general cargo. As part of the very large era of sail freighters, where crew were expensive, the Preussen had no engines for propulsion, but two "Donkey Engines" which powered winches, pumps, and ship's gear, meaning she needed a crew of only 45. Steel had been used throughout her construction, making her a strong and steady ship, able to take the stresses involved in running at high speeds in heavy weather. She circumnavigated the globe, and went around the Horn at least a dozen times. Preussen served until November of 1910, when she was rammed by a Steamer in the English channel. The collision caused significant damage, nearly tearing the bowsprit off the ship and flooding the forward compartments. Luckily, the ship had been constructed with watertight bulkheads, otherwise she may well have sunk. Three tugs attempted to tow her into Dover, but a storm drove her on the rocks and she ran hard aground, flooding with up to 16 feet of water in the holds. She was deemed unsalvageable, cargo was pulled off onto barges, and the Preussen's career ended far earlier than anyone anticipated. An account of the collision from the Preussen's Helmsman is available here. It includes a detailed description of the ship's equipment and accommodations, as well as the account of the collision and grounding. AuthorSteven Woods is the Solaris and Education coordinator at HRMM. He earned his Master's degree in Resilient and Sustainable Communities at Prescott College, and wrote his thesis on the revival of Sail Freight for supplying the New York Metro Area's food needs. Steven has worked in Museums for over 20 years. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's Note: The following text is a verbatim transcription of an article written by George W. Murdock, for the Kingston (NY) Daily Freeman newspaper in the 1930s. Murdock, a veteran marine engineer, wrote a regular column. Articles transcribed by HRMM volunteer Adam Kaplan. Belle Horton Constructed as a replacement for a steamboat that had been destroyed by fire, the “Belle Horton” was in service for 25 years on various routes and finally was also the victim of the flames which brought to a close the careers of many of the Hudson river steamboats. The wooden hull of the “Belle Horton” was built by Van Loan and Magee at Athens, New York, in 1881, and her engine- a vertical beam type with a cylinder diameter of 32 inches with a seven foot stroke- was the product of Fletcher, Harrison and Company of Hoboken, New Jersey. The vessel’s hull measured 135 feet, six inches in length, with a breadth of beam listed at 25 feet five inches, and a depth of hold of seven feet five inches. Her gross tonnage was listed at 305, and her net tonnage at 224. The “Belle Horton” was built for the Citizens’ Line of Troy to take the place of the steamboat “Golden Gate,” which had been destroyed by fire during the summer of 1880. Due to the shallow water in the upper Hudson river between Troy and Albany, the larger night boats, “City of Troy” and “Saratoga,” sometimes experienced difficulty in navigating the river between these two cities, and the “Belle Horton” was often used as a tender to these two larger vessels. Because of her fine lines and graceful appearance the “Belle Horton” became a favorite with the river-minded public and she was used frequently for excursion parties on the upper Hudson river during the summer months. The year of 1894 marked the end of the steamboat “Belle Horton” in excursion service, and she was then chartered out to run between Newark and New York. The following two years, 1895 and 1896, found the “Belle Horton” in service between Keyport, N.J., and New York on the route formerly traversed by the steamboat “Magenta,” which had been chartered to run between the Battery, in New York city, to Bay Ridge, Brooklyn. During the time of the Spanish-American War, 1897-1898, the “Belle Horton” was running between New York city and Norwalk, Conn., and in 1899 she was returned to Troy where she was again used for excursion purposes. For one month during this period in her career the “Belle Horton” was in service between Peekskill and New York, replacing the steamboat “Chrystrah,” which was laid up for repairs to a broken shaft. The beginning of the 20th century closed the career of the “Belle Horton” on the waters of the Hudson river. The trim little steamboat was sold and taken to Norfolk, Va., where she was placed in service as an excursion boat on the James river. She sailed the James river between Norfolk and a place called Pine Beach, and the name “Belle Horton” disappeared from her sides- giving way to the name “Pine Beach.” In 1906, after a quarter of a century of service, the “Pine Beach” was destroyed by fire- thus erasing from active service the steamboat which had been known to travelers of the Hudson river as the “Belle Horton.” AuthorGeorge W. Murdock, (b. 1853-d. 1940) was a veteran marine engineer who served on the steamboats "Utica", "Sunnyside", "City of Troy", and "Mary Powell". He also helped dismantle engines in scrapped steamboats in the winter months and later in his career worked as an engineer at the brickyards in Port Ewen. In 1883 he moved to Brooklyn, NY and operated several private yachts. He ended his career working in power houses in the outer boroughs of New York City. His mother Catherine Murdock was the keeper of the Rondout Lighthouse for 50 years. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

The Hudson River Maritime Museum has an extensive collection of oral histories interview of Hudson River commercial fisherman, including fisherman Edward Hatzmann, who was interviewed on April 25, 1992. Below, Hatzmann recalls a story told to him by fellow fisherman Charlie Rohr, about a prison break from Sing Sing Prison in Ossining, New York.

Unlike some fishermen's tales, this one was really true! Fisherman Charlie Rohr really did have to deal with the prisoners. He was interviewed for the Yonkers, NY Herald Statesman in an article published April 14, 1941. The article is transcribed in full below:

"'We're Going To Bump You Off!' Killers Promise Charlie Rohr. But Shad Fisherman, Who Rowed Fugitives Across Hudson, Talks Them Out of It and Escapes Alive" OSSINING - Charlie Rohr is alive today, but from now on he feels he's living on borrowed time. Rohr is the shad fisherman who rowed two desperate escaped convicts across the Hudson River and then talked himself out of being their third victim. "It was pretty tough sitting there with two guys holding guns to you," Rohr reported, "but it didn't do any good to lose your head." Rohr and another fisherman were getting their equipment together in their shack shortly before 3 A.M., preparatory to rowing out to their weirs. A series of shots broke the pre-dawn stillness but the men didn't pay much attention to it. "I thought it was just a brawl," Rohr said. The other fisherman went upstairs for a minute, and Rohr stepped to the door of the shack on Holden's Dock. Two men, white-shirted and in the gray trousers unmistakably of Sing Sing Prison, confronted him. Two guns were held against his stomach. "Is this your boat?" one growled. "Yes," said Rohr. "Get going then," he was told. "And fast - we've just killed a cop." Rohr wasn't having any. "You take the boat," he urged. "You're rowing," he was told. "Get going." The trip across the river took an hour - the longest hour of Charles Rohr's life. The thugs sat in the center and stern seats of the boat, and trained their guns upon him during the entire trip. Rohr worked the oars, and then men whispered back and forth. The fisherman pulled up at a point near Rockland Lake on the west bank. The convicts prepared to leave the boat. "Now," said one in an expressionless voice, "we're going to bump you off." "Listen," said Charlie Rohr, his mind working faster than it ever had before, "that won't do you no good." The men paused. "I'm well known around here, see? Everyone knows my boat. And if you knock me off, and the boat's around here, everyone is going to know what happened and where you guys got away." They were still listening, so Rohr kept on. "What you'd better do is let me go back. Then no one's going to know anything about this." Four eyes regarded him coldly. Then the pair whispered together for a minute. Charlie Rohr held his breath, and then his heart leaped. The men jumped from the boat and ran into the woods on the shore of Rockland County. He rowed back across the river with shaking knees.

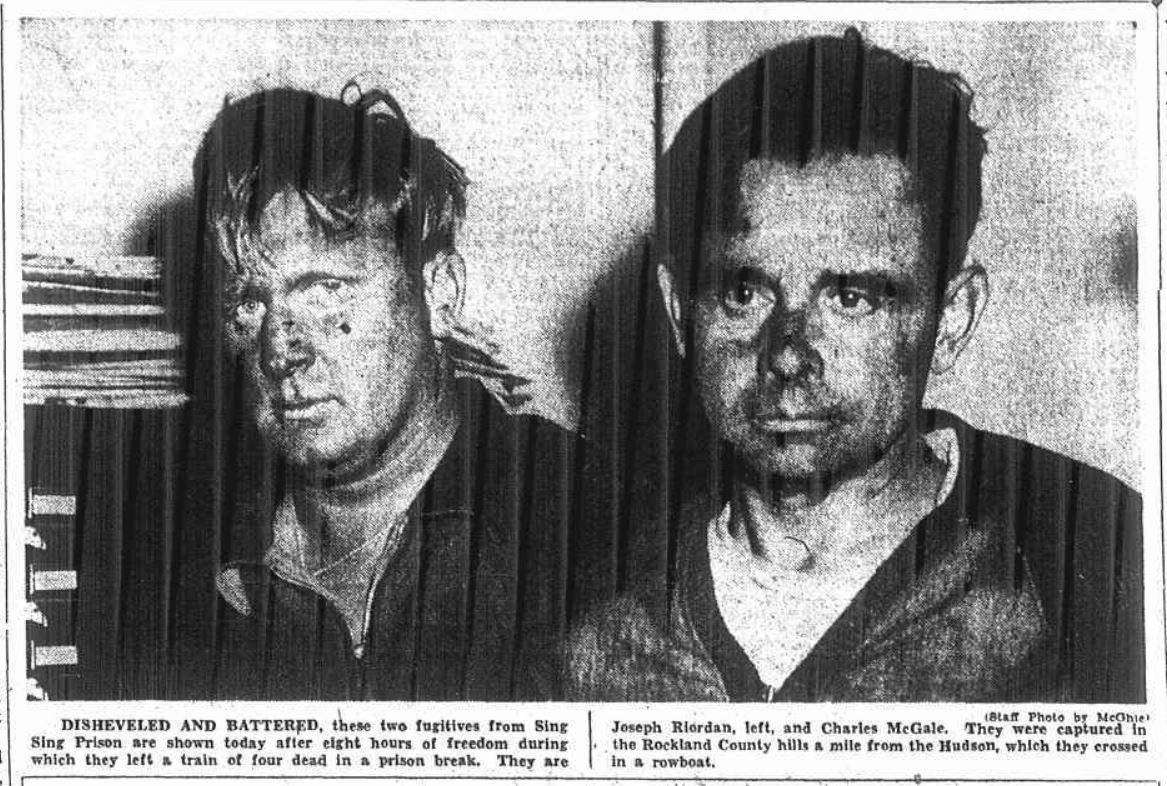

"Disheveled at battered, these two fugitives from Sing Sing prison are shown today after eight hours of freedom during which they left a train of four dead in a prison break. They are Joseph Riordan, left, and Charles McGale. They were captured in the Rockland County hills a mile from the Hudson, which they crossed in a rowboat." caption of photograph from Yonkers "Herald Statesman" front page, April 14, 1941.

Joseph Riordan and Charles McGale were caught in Rockland County and returned to prison. Charlie Rohr went back to fishing.

If you'd like to hear more stories from Edward Hatzmann, check out his full oral history interview, available on New York Heritage. For more fishermen's oral history interviews, check out our full collection.

If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Welcome to Sail Freighter Fridays! This article is part of a series linked to our new exhibit: "A New Age Of Sail: The History And Future Of Sail Freight In The Hudson Valley," and tells the stories of sailing cargo ships both modern and historical, on the Hudson River and around the world. Anyone interested in how to support Sail Freight should also check out the Conference in November, and the International Windship Association's Decade of Wind Propulsion. For today's Sail Freighter Friday, we're going to go back a ways further historically than last week, but only about 2,100 or so years. This week, we'll be looking at the type of sailing cargo vessels of the Mediterranean Sea which built much of the ancient Greek, Roman, and Carthaginian empires of the classical world. They were advanced sailing craft plying well developed trade routes, and supplying some of the largest cities of their time with food, stone, metals, ceramics, timber, wool, cement, firewood, glass, charcoal, livestock, and more from all over the Mediterranean basin. In tonnage and fleet strength, they were likely unsurpassed from the decline of the Roman Empire until the Renaissance, a period of nearly 1,000 years. Ships in this period, roughly 2300-2000 years ago, were wooden, constructed in what we would now call a mortise-and-tenon, shell-first construction, with frames added second. They usually also had an additional layer of planking on the inside of the frames. This is rarely used today, but was stronger than "stitched" or "sewn" construction of previous eras, and allowed for much larger vessels of up to 600 tons to be built routinely. Their wide, relatively shallow hulls were reasonably stable, and propelled by up to three square-rigged masts. The size and number of ships on the Mediterranean Sea in this period began to increase, as cities grew in population and trade increased. Grain, wine, and olive oil from Egypt and Syria, as well as Spain and North Africa, were essential to keeping Rome fed, and the voyage could take weeks against contrary winds, resulting in the need for a large fleet with seasonal availability. It also meant that the ships had to be tough and seaworthy, which they were, but they weren't necessarily fast: Some made an average of barely 2 knots per hour when sailing against the wind. Downwind, they could make average speeds of just over 6 knots. These sailing craft were the result of many generations of development and cultural exchange between the Greeks, Egyptians, Phoenicians, Iberians, Romans, and Latins, ideally suited to their environments and available materials. Without them, the cultural and material exchange which allowed these cultures to flourish would have been impossible, as would many of the future developments in navigation and shipbuilding which are discussed in this series. Unfortunately, they also had a profound ecological impact: Despite their being built of wood, a renewable resource, the demand for ship timbers and fuel was higher than the forests growth rates at many points, and led to deforestation and desertification which still has effects on the local ecosystems today. With a modern understanding of forest management, this can be avoided, but there is a limit which must be worked within to keep both a healthy forest, and a healthy fleet. If you're interested in these ancient ships, their construction, and use, I recommend starting with Sailing From Polis To Empire, available free as an E-Book at the link. AuthorSteven Woods is the Solaris and Education coordinator at HRMM. He earned his Master's degree in Resilient and Sustainable Communities at Prescott College, and wrote his thesis on the revival of Sail Freight for supplying the New York Metro Area's food needs. Steven has worked in Museums for over 20 years. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor’s Note: The following text is a verbatim transcription of an article featuring stories by Captain William O. Benson (1911-1986). Beginning in 1971, Benson, a retired tugboat captain, reminisced about his 40 years on the Hudson River in a regular column for the Kingston (NY) Freeman’s Sunday Tempo magazine. Captain Benson's articles were compiled and transcribed by HRMM volunteer Carl Mayer. See more of Captain Benson’s articles here. This article was originally published September 9, 1982 in the "Ulster County Gazette". By William O. Benson as told to Ann Marrott SLEIGHTSBURGH — Labor Day on the Hudson signified the last runs of the excursion steamers for the summer — especially for the people who had come up from New York City to spend the summer around the Catskill Mountains and Kingston. It always seemed that on Labor Day, people didn’t appear so happy — especially the children. When you saw the boats come up in early June or July, the children would be so happy. But when getting on the boats going back Labor Day Weekend, they would all be nice enough, but there would be no joy. Labor Day was one holiday I hated as a boy, because the next day I had to go to school. The Hudson River Day Line would run extra boats on Saturday and Sunday and Labor Day. And if you were out on Kingston Point on that holiday there would be a number of boats coming out of New York to bring the people back. Everyone wanted to get home the day before school started. All those boats would be loaded going to Bear Mountain. The Central Hudson Line would be running boats up to Beacon, Newburgh and Poughkeepsie. Labor Day was also the last excursion of the “Homer Ramsdell” and it would be advertised in the papers. Now, if you brought the New York World back then you would see two whole pages full of steamboat listings. There would be steamboats listed there that people today have probably never heard of, such as the “Grand Republic,” the “Commodore,” the “Benjamin Franklin” and the “Sea Gate.” The “Sea Gate” could carry 500 to 600 people. But the bigger boats you would see would be the “Benjamin E. Odell,” the “Robert Fulton,” the “Albany,” the “Onteora,” and the “Clermont.” Some of the big Day Line boats could carry 3,000 or 4,000 people. The “Washington Irving” could carry 6,000 people. I remember one Labor Day on the “Albany.” A lot of people got off her at Bear Mountain and this poor, stout woman came rushing down the pier, screaming and yelling. Her children were on the boat and it was already leaving. So the mate yelled back to her, “We'll put them off at Newburgh in charge of the dockmaster there. You'll have to get them at Newburgh.” Anyway, the purser took them under his wing and when they got to Newburgh the dockmaster took care of them. I’m not sure how they made out, but I’m sure they were fine. You used to see that all the time!! The[n] after Labor Day the boats would get back to their regular schedules. Most of the captains on those boats, especially George Greenwood, the captain of the “Benjamin B. Odell,” were always glad to see Labor Day come. George was always worried with so many people on the boat during the summer excursions, of a fire starting in the staterooms. Some of the boats did run after Labor Day on a Saturday or a Sunday to carry passengers to Bear Mountain or an excursion out of Kingston, but they wouldn’t have the big crowds. I looked forward to Labor Day, too, when I worked on the boats. You knew the boats were going to only run another day or two. Then she was headed for the Rondout Creek to tie up for the winter and you could go home. All during the summer you never got home much on those boats. Whatever boats were the most expensive to run were tied up first — right after Labor Day. The Day Line, after the holiday, operated only two boats. Sometimes for two weekends in September they would have, for example, the “Robert Fulton” ready to come out for a fall excursion to see the Hudson River fall foliage. When the boats were tied up we worked on them until the first of November cleaning the boat and painting her. Then of course you were laid off for the winter. In those days if you saved $150 to $200 during the summer you would have it made. You could live very comfortably all winter long. Some of us would get jobs ashore, which I used to do. I always looked forward to spring, when I could get back on the boats. After Labor Day — during the fall and winter — was the busiest time for workmen in the Cornell Steamboat Company shops. When the river was freezing over and navigation was closing, that’s when they started to repair and clean up the boats. Sometimes they would employ 400 or 500 men during the winter. They had the boiler gang, machinists, sawyers, painters, blacksmiths, the coaling gang and the bull gang—they did all the heavy work. They also had a lot of white collar workers. Everyone worked to get the boats ready for the next season. AuthorCaptain William Odell Benson was a life-long resident of Sleightsburgh, N.Y., where he was born on March 17, 1911, the son of the late Albert and Ida Olson Benson. He served as captain of Callanan Company tugs including Peter Callanan, and Callanan No. 1 and was an early member of the Hudson River Maritime Museum. He retained, and shared, lifelong memories of incidents and anecdotes along the Hudson River. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

In honor of the attacks on the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001, we are sharing one of our favorite and most poignant documentary films about that day, "Boatlift." "Boatlift" chronicles the marine evacuation of lower Manhattan during the attacks. Narrated by Tom Hanks, this short film highlights the ordinary people who stepped up to help strangers in a time of crisis. If you would like to learn more about the evacuation and the people involved, read Jessica DuLong's book Saved at the Seawall: Stories from the September 11 Boat Lift or catch up on her 2021 lecture for the Hudson River Maritime Museum, "Heroes or Human: September 11th Lessons on the 20th Anniversary," as recorded below. Jessica DuLong shares the dramatic story of how the New York Harbor maritime community delivered stranded commuters, residents, and visitors out of harm’s way on September 11, 2001. Even before the US Coast Guard called for “all available boats,” tugs, ferries, dinner boats, and other vessels had sped to the rescue from points all across New York Harbor. In less than nine hours, captains and crews transported nearly half a million people from Manhattan. This was the largest maritime evacuation in history. DuLong’s talk, and her book Saved at the Seawall, highlight how people come together, in their shared humanity, to help one another through disasters. Actions taken during those crucial hours exemplify the reflexive resourcefulness and resounding goodness that reminds us of the hope and wonder that’s possible on the darkest days. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Welcome to Sail Freighter Fridays! This article is part of a series linked to our new exhibit: "A New Age Of Sail: The History And Future Of Sail Freight In The Hudson Valley," and tells the stories of sailing cargo ships both modern and historical, on the Hudson River and around the world. Anyone interested in how to support Sail Freight should also check out the Conference in November, and the International Windship Association's Decade of Wind Propulsion. The Morning Star was a sloop based out of the Rondout Creek in the 1790s, and many of her records were included in Paul Fontenoy's 1994 study of Hudson River Sloops. As a result, we can do some analysis of not only this one sail freighter, but her cargos and the exports of the Rondout Creek in her era, without spending dozens of hours in archives. This is a good thing, because there's a lot of lessons to be taken from her records. As a Hudson River Sloop, she was designed for our specific waters, with a shallow draft, drop-keel to make sailing upwind easier when enough water was available, and a simple fore-&-aft rig. These elements made the Hudson River Sloops ideally suited to the shifting mudflats and variable winds of the Hudson. In addition, they required relatively few crew members to handle the two or three sails. As for cargo, while the records aren't listed in tons, we can see a lot of patterns in her bills of lading. Passenger and cargo business was essential for the Sloops, and most passengers were headed North. Most of the cargo, however, was headed South to New York City and beyond. The cargo was principally agricultural goods, which were either used in the city or traded on in the West Indies Provisions Trade. The Hudson Valley was the breadbasket of the West Indies and parts of Southern Europe, but this trade to the West Indies allowed for the constant mono-cropping of sugar on those islands. New York and the Hudson Valley made much of its money off the Slave Trade both directly and indirectly through the provisioning trade. The agricultural trade profit which motivated the settlement and agricultural growth of the Hudson Valley in the 17th and 18th century is inseparable from the Slave Trade. Returning to the technical side of the discussion, we can also see the sailing season and voyage times from the records of Morning Star. With a 258 day sailing season and 11 voyages, the average duration of a round trip is about 24 days. March must have coincided with the river ice clearing, and December with the ice becoming enough to discourage sailing. The other thing to notice is how profitable the Sloops were. With a nearly 75% return over expenses, this is a very encouraging business. Profits were boosted by the lack of competition from steam propulsion, in the form of either trains or steamships. As that changed over the next 100 years, the profit margin of sloops declined, but in 1793 they gave a very significant return. Anyone interested in the technical details of the Hudson River Sloops should find a copy of Fontenoy's book, as it contains a well researched and easily read account of their development and operations for over 200 years. AuthorSteven Woods is the Solaris and Education coordinator at HRMM. He earned his Master's degree in Resilient and Sustainable Communities at Prescott College, and wrote his thesis on the revival of Sail Freight for supplying the New York Metro Area's food needs. Steven has worked in Museums for over 20 years If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's note: The following text was originally published in New York newspapers from 1796 to 1800. Thanks to volunteer researcher George A. Thompson for finding, cataloging and transcribing these articles. The language of the articles reflect the time period when they were written. {letter from S. Howard, addressed to the Mayor] Being born in the city of London, and having had many opportunities of being an eye-witness to the amazing effects of the FLOATING ENGINES, it surprises me that you are without them, as no city in the world is better situated for water. Two Engines would be sufficient for the purpose, which may be brought from London, and here fixt in proper Barges: the cost I will answer will not be more than 800.. Proper moorings be laid down for them, one opposite the Fly-Market, in the East River, the other opposite in the North-River, they will then be ready to move to any part where the fire should break out, and in that situation they will be able with the assistance of leather pipes of sufficient length, to meet and jointly play to the top of any house in William street. . . . if the fire should break out near the water side, as was the case at Murray's wharf, the whole block of houses would have been saved. . . . You will want no buckets, nor need you fear the want of water as long as there is water in the Rivers. The Barges are constructed with wells like those of your Fishing Boats. . . . *** D Advertiser, January 4, 1796, p. 2, col. 1. The fire at Murray's wharf started December 9, 1796. The Engines lately brought from England is ordered for public inspection THIS DAY, at 1 o'clock, opposite the Tontine Coffee-house. The Floating Engine cannot be worked till the barge is built; which will take up one month; it will then be exhibited for the inspection of the public. N-Y Gazette & General Advertiser, November 10, 1800, p. 3, col. 1. [letter advocating a floating fire-engine] . . . even in this severe season, when there is almost an impossibility of getting water from the quantity of ice that surrounds the city: -- say the Barge that the Engine is in being fixt in the ice . . . , yet still there is no danger that the Engine will not work, as it draws the water from the bottom of the river. . . . *** *** I have observed that when a fire unfortunately happens, the bells are set to work, which sounds are really terrifying -- to the fair sex I am sure it must be shocking -- and serves the purpose of calling together a set of people whose business, I am sorry to say, is too frequently nothing but plunder. . . . THOMAS HOWARD. N-Y Gazette & General Advertiser, January 18, 1797, p. 2, col. 4. [two floating fire engines arrive from London] N-Y Gazette & General Advertiser, October 28, 1800, p. 3, col. 1. By desire of several gentlemen, the Fire Engines lately imported into this city, are to be tried to-morrow, 12 o’clock, at Burling-slip (if fair weather.) The Firemen are respectfully desired to attend in order that they may have a fair trial, both by suction from the wet, and by the leaders into Pearl-street. Commercial Advertiser, November 20, 1800, p 3, col. 1. [store belonging to Mr. Saltus, Front-street, burns; $100K in damages] Commercial Advertiser, December 15, 1800, p,. 3, col. 2; [praise for "the new modelled Engines lately brought to this city"] The great utility and advantage of these new engines was very conspicuous; for they not only supplied other engines with water without the aid of a single bucket, but were likewise eminently useful in throwing a much larger quantity of water on the flames than any other engines in this city were capable of doing. Commercial Advertiser, December 17, 1800, p. 3, col. 2. On Friday evening last the ship Thomas, owned by Thos. Jenkins, of Hudson, laden with 1700 hhds flax seed, and a quantity of flour and pot ashes, drifted on shore at Corlaer's Hook and bilged; she was freighted and cleared out for Londonderry, and has now 6 or 8 feet water in her hold; but it is expected she will be got off with part of her cargo. The fate of this ship is very singular: she was formerly the Admiral Duncan, of Liverpool, and was burned to the water's edge at this port, with a valuable cargo, after being cleared for Europe, precisely a twelve month previous to her present disaster. Commercial Advertiser, January 19, 1801, p. 3, col. 1 Last evening about 9 o'clock fire was proclaimed from all directions. The armed ship Admiral Duncan, laying at the [illegible] wharf near Coenties Slip, took fire, and in a few minutes after the discovery, was enveloped in flames -- she was cut loose and towed into the stream, where she continued till [about] 2 o'clock this morning, when, in spite of every effort, she drifted back, (the wind being high at N. E.,) and fortunately lodged on the rocks on the point of the battery, where she burnt to the water's edge. *** Commercial Advertiser, January 18, 1800, p. 2, col. 5 Ship THOMAS -- late ADM. DUNCAN. WE, the owners of the above ship, return our thanks to the Mayor and Corporation for the loan of the late imported Fire Engine, to raise the said ship; which, with every possible assistance, we have accomplished. At the same time, we are sensible of the service and assistance of Mr. Howell, who was directed by the Corporation to take charge of the same. . . . It is a pleasing circumstance to learn from the above letter, that we are now in possession of Engines that are found to be useful on more occasions than extinguishing fires. It was never before suggested that they might be applied to the raising of ships or vessels sunk, but of which the circumstance above mentioned gives a most decided proof of their utility. . . . Commercial Advertiser, January 28, 1801, p. 3, col. 1 If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

|

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 [email protected] Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |