History Blog

|

|

|

|

|

Welcome to Sail Freighter Friday! This article is part of a series linked to our new exhibit: "A New Age Of Sail: The History And Future Of Sail Freight In The Hudson Valley," and tracks sailing cargo ships both modern and historical. Anyone interested in how to support Sail Freight should also check out the Conference in November, and the International Windship Association's Decade of Wind Propulsion. Schooner Apollonia is one of our favorite Sail Freighters, because she's on the Hudson River right now. She has been carrying cargo for two years now, with a bit of a preview season in 2020, testing out cargos and becoming familiar with regional waterfront infrastructure. Apollonia is currently the only active sail freighter in the US. Apollonia is a 64' steel schooner built in Baltimore in 1946. Designed to carry cargo or operate as a pleasure yacht, she was purchased on Craigslist after spending 30 years on the hard and refitted as a cargo vessel. She was under restoration for four years before arriving at the Hudson River Maritime Museum in the fall of 2019 to build wooden blocks as she built out her full rigging. Her first official season was in 2021, when the vessel made 55 port calls at 15 ports on the Hudson River and in New York Harbor. Today she is homeported in Hudson NY, and often visits the Hudson River Maritime Museum docks as she works to connect the Hudson Valley and New York City. Captained by Sam Merrett, Apollonia carries a lot of malted grain for breweries as the main part of her cargo, but she also carries almost anything else: Solar panels, cider, hot sauce, beer, coffee, maple syrup, flour, honey, yarn, apparel, books, vegetables, red oak logs for a mushroom farm, were all on the list in 2021, and more will be involved in 2022. She can carry 10 tons (20,000 lbs) of cargo at a time, up to 600 cubic feet. Apollonia is a critical link in relearning the craft and trade of working sail. Inspired by the Vermont Sail Freight Project's Ceres, the project is a combination of sail freight and localized food economy with many educational side benefits. Apollonia builds connections between people and the river, as well as between businesses shipping goods sustainably by wind power, with first- and last-mile on-shore aspects done with a solar-powered cargo bike and trailer. You can find out more about the Apollonia's Impacts from the 2021 season here, and check out her schedule and cargos for 2022 - and get involved as a "Shore Angel" or sail freight customer - at her website. If you find her at the docks anywhere on her route this season (there's a tracker on the website), she has a mobile component of our new exhibit aboard, which is worth checking out. Apollonia is also partnering with the Museum for the Northeast Grain Race and the Sail Freight Conference in November. AuthorSteven Woods is the Solaris and Education coordinator at HRMM. He earned his Master's degree in Resilient and Sustainable Communities at Prescott College, and wrote his thesis on the revival of Sail Freight for supplying the New York Metro Area's food needs. Steven has worked in Museums for over 20 years. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

0 Comments

The Hudson River Maritime Museum recently received a set of black and white photographs documenting the work of the Kingston Shipbuilding Corporation during World War I. Clyde Bloodgood worked at the shipyard located on Island Dock. Shipbuilding has been going on for the last couple of hundred years along Rondout Creek. William duBarry Thomas writes in the 1999 Pilot Log: "During World War I, the Kingston Shipbuilding Corporation constructed ocean-going wooden-hulled cargo steamships (the only vessels of the type ever built along the Creek)" The museum is grateful for the donation of these fine photographs. They are a wonderful addition to the museum's collection and aids in our ability to tell the history of the Hudson River and its tributaries. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

In the spirit of Earth Day last week, for today's Media Monday, we are sharing information about dam removal in the Hudson River Valley. According to the NYS Department of Environmental Conservation, the Hudson River watershed has more than 1,600 dams and as many as 20,000 culverts. Most of these are remnants of the Hudson Valley's industrial past. Although dams can play an important role in flood mitigation and hydroelectric power generation, they also serve as barriers to migratory fish such as herring who swim up the Hudson's tributary creeks and streams to spawn. Of particular concern are abandoned dams in poor repair. In 2019, Riverkeeper worked with documentary filmmaker Jon Bowermaster to produce the short documentary film, "Undamming the Hudson River," all about the science and efforts behind removing abandoned and unnecessary barriers to the watershed. Watch below for the full film. Learn more about dam removal efforts in the Hudson River watershed:

If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

In May of 2022, the Hudson River Maritime Museum will be running a Grain Race in cooperation with the Schooner Apollonia, The Northeast Grainshed Alliance, and the Center for Post Carbon Logistics. Anyone interested in the race can find out more here. Rebuilding an industry that has been effectively dead for a century is no easy task. It is made harder by economic and political forces which make competing technologies artificially cheaper, transport infrastructure designed for use by a single technology, and a lack of public interest. These are the principal challenges to a Sail Freight future, and it should be noted that none of them are technical in nature. Humanity has been moving cargo under sail for tens of thousands of years, and continues to do so. The changes needed for a Sail Freight future are mostly cultural and social. Three keys are needed to get Sail Freight into the transportation mix at scale. The first is a change in speed requirements. As long as next day shipping is demanded at all costs, sail freight is less viable. When this social construct can be changed to allow for slower and less certain transportation, of both food and other goods, Sail Freight becomes viable. The second is based in social infrastructure. The networks of shipping relations by sail need to be rebuilt, between sailors and those sending and receiving goods. Within the food system, this can be quite complex, but is starting to make a recovery within local food systems. As the fleet expands, these relationships must expand as well. The third adaptation we will need to make for Sail Freight to be viable is increasing the economic cost of other means of transport. This will happen with the rise of carbon taxes, fuel scarcities, and other challenges which are likely to be part of the coming energy transition. At about $8/gallon of diesel fuel, Sail Freight at competitive wages and full crews will be highly competitive with long distance trucking and rail transport. The final challenge is to have a sufficient fleet of sail cargo vessels built and afloat, with sufficient sailors to crew them when the above conditions are met. This can all be accomplished if we set our minds to it, and then the more trivial matters of setting up brokerages, freight offices, and warehouses will be essentially trivial. To build a sustainable world, we have a lot of work to do. Thankfully, the work is clear and achievable if we choose to do it. You can find more information on the Grain Race here. AuthorSteven Woods is the Solaris and Education coordinator at HRMM. He earned his Master's degree in Resilient and Sustainable Communities at Prescott College, and wrote his thesis on the revival of Sail Freight for supplying the New York Metro Area's food needs. Steven has worked in Museums for over 20 years. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Today is Earth Day, and what better way to celebrate than with a roundup of amazing Hudson River environmental history? Read on to learn more about some of the people and organizations that have had a big impact on the health of the Hudson River, and the American environmental movement.  Women in the Forest: Tree Ladies and the Creation of the Palisades Interstate Park On September 22, 1897, Mrs. Edith Gifford boarded a yacht on the Hudson River along with other members of the New Jersey State Federation of Women’s Clubs (NJSFWC) and male allies from the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society (ASHPS). The goal of this riverine excursion was to assess the horrible defacement of the Palisades cliffs by quarrymen, who blasted this ancient geological structure for the needs of commerce—specifically, trap rock used to build New York City streets, piers, and the foundations of new skyscrapers. All on board felt that seeing the destruction firsthand, with their own eyes, was the first step in galvanizing support for a campaign to stop the blasting of the cliffs.  Remembering Theodore Cornu: Unacknowledged Father of Environmentalism Theodore J. Cornu was born in New Jersey to a Swiss mother and father, the latter of whom soon abandoned Cornu, his mother and siblings. The young Cornu demonstrated an affinity for art early on and eventually found his way to a Manhattan engrossing studio, where he soon became employed as an “engrosser” hand lettering diplomas and other commemorative documents. Canoeing was popular amongst his engrossing colleagues, which led him to the boating community in Ft. Washington. His love for canoeing seems to have catalyzed his interest in both the Hudson River and Native American customs.  Robert Boyle, Hero of the Hudson If ever a man loved a river, Robert Hamilton Boyle Jr. loved the Hudson — and he was not afraid to shout his love from the rooftops. In his classic text, The Hudson River: a Natural and Unnatural History (1969), Boyle makes his feelings abundantly clear with the book’s very first line. “To those who know it,” wrote Boyle, “the Hudson River is the most beautiful, messed up, productive, ignored and surprising piece of water on the face of the earth. There is no other river quite like it, and for some persons, myself included, no other river will do. The Hudson is the river.”  The Origins of Riverkeeper In March 1966, a small group of recreational and commercial fishermen, concerned citizens and scientists met at a Crotonville American Legion Hall intending to reverse the decline of the Hudson River by reclaiming it from polluters. With them was Robert H. Boyle, an angler and senior writer at Sports Illustrated, who was outraged by the reckless abuse endured by the river. At the group’s initial meeting, Boyle announced that he had stumbled across two forgotten laws: The Rivers and Harbors Act of 1888 and The Refuse Act of 1899. These laws forbade pollution of navigable waters in the U.S., imposed fines for polluters, and provided a bounty reward for whoever reported the violation. After listening to Boyle speak, the blue-collar audience agreed to organize as the Hudson River Fishermen’s Association, and dedicate themselves to tracking down the river’s polluters and bringing them to justice.  History of the Sloop Clearwater Most people familiar with CLEARWATER know the sloop was the brainchild of the late American folk legend and activist Pete Seeger. Pete was an idealist and an optimist. He once wrote, “There is a little Don Quixote in all of us.” You couldn’t tell him something couldn’t be done. But when you take a closer look at CLEARWATER’s story, it’s a miracle the boat was ever built at all. At the time CLEARWATER was built, the “tall ship revival” was still a decade or two away. Yes, the first Operation Sail brought tall ships from around the world to New York Harbor in 1964, but no one was building new tall ships with one or two exceptions. There were vessels built that were replicas of specific ships, such as the MAYFLOWER II, launched in 1956, and the HMS BOUNTY, launched in 1962 and built specifically for the filming of Mutiny on the Bounty. But to form a new not-for-profit to build a replica of a type of ship -- not even a famous historic ship? Nobody was doing that. Seeger and the fledgling Clearwater organization were ahead of the curve.  Preservation and Perseverance: Pillars of Scenic Hudson's Grassroots Legacy Scenic Hudson improves the health, quality of life and prosperity of Hudson Valley residents by protecting and connecting them to the Hudson River and the region beyond. Ever responsive to the changing pulse of the region, the ways we achieve our mission are always evolving. Our work today builds upon more than five decades of advocacy and citizen engagement. When Scenic Hudson was founded in 1963, grass-roots environmental activism did not exist as it does today. Con Edison’s plan to construct a hydroelectric plant on the face of majestic Storm King Mountain in the Hudson Highlands changed that. If you'd like to learn more about the role of the Hudson River in American environmentalism, check out our online exhibit "Rescuing the River: 50 Years of Environmental Activism on the Hudson," which is now a traveling exhibit and currently on view at the Newburgh Free Library. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Happy Earth Week! Wednesday is Earth Day, so today's Media Monday features a 1941 Encyclopaedia Britannica Film describing the sources of city water supplies with a focus on the New York City Water system from the Catskill Mountains reservoirs to the faucets of New York City. Video courtesy of archive.org.

Last fall we hosted author and historian Frank Almquist for a discussion of the construction of the Ashokan Reservoir as part of our Follow the River Lecture Series. You can watch the recorded lecture below:

Want to know more? Check out these previous blog posts about New York's water supplies:

If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

On April 10, 1912, New York marine artist Samuel Ward Stanton was waiting to board the RMS Titanic. A prolific artist and chronicler of American steamboats, he had spent the previous months traveling in Europe, researching and preparing sketches of the Alhambra and other Spanish scenes associated with author Washington Irving. He had intended to use these in his commission to design and decorate some of the interiors of the new Hudson River Day Line steamboat named Washington Irving, the largest of the Day Line “Flyers” ever built. Stanton was likely thrilled to board the new and sensational RMS Titanic at Cherbourg with muralist Francis Davis Millet for her inaugural voyage to New York. One imagines he may have prepared a drawing or two of her majestic bow and her opulent interiors before packing them in a portfolio crammed full of European scenes. Samuel Ward Stanton was born in Newburgh in 1870 to Samuel Stanton and Margaret Fuller. Samuel Sr. was a principal of the Ward, Stanton & Company shipyard which was created out of the bankrupt Washington Iron Works at the foot of Washington St. in 1872. Before failing, the iron works had produced naval machinery, steam engines, boilers, sawmills and sugar mills. The new company continued to produce machinery but grew to emphasize iron shipbuilding. Samuel Ward Stanton grew up in and around the yard observing the scene and becoming a talent with pencil and pen. He also assembled scrapbooks detailing steamboats and their histories which became important sources for the articles and books he published as a young man. In 1884, the family moved to Florida aboard a small, iron sidewheel steamboat they built for themselves. The steamboat included the machinery for a sawmill, which was assembled upon arrival and put to immediate use in building a house and presumably selling lumber to other newcomers. The yard in Newburgh later became the famous T.S. Marvel Co. shipyard. As an adult, “Ward” Stanton, as he was known to his friends, returned to New York and developed a distinctive pen and ink style that emphasized the details of the ships and boats that he documented. He became acquainted with New York marine artist James Bard (1815-1897) who became a friend and an important source of information for those boats no longer available for direct observation. He later provided financial assistance to Bard’s daughter Ellen out of deep respect for the late pioneering steamboat painter. Stanton earned a bronze medal at the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893 for his collection of Erie Canal drawings and in 1895 published his seminal American Steam Vessels, the first in a series of illustrated books by Stanton illustrating the history of steam navigation. He wrote and produced illustrations for periodicals including Seaboard Magazine, Marine Journal and the Nautical Gazette and his illustrations appeared in other books on steam navigation and regional history. He began producing murals and promotional art for the Hudson River Day Line, notably a series of car cards advertising the line’s “flyers.” Stanton painted a series of steamboat history scenes for the 1909 Robert Fulton and was active in the 1909 Hudson Fulton Celebration. He also prepared art for the Catskill Evening Line and the Nantasket Beach Steamboat Co. As Stanton boarded the RMS Titanic with Francis David Millet, he could never have imagined the disaster that lay ahead of him. Just four days later, on the evening of April 14, 1912, the Titanic struck an iceberg, and by the early morning of April 15, had sunk. Stanton was not among the survivors. He was just 42 years old. What happened in his last hours remains unknown, and his European work in all likelihood perished with him. One account indicates that a black coat bearing a letter inscribed “W. anton” was recovered in Canada and sent to his wife Cornelia. Sadly, the sinking of the Titanic meant that Samuel Ward Stanton never returned to New York to finish his work for the Washington Irving - it was completed in 1913 with references to Irving’s tales including the Alhambra reading room completed by other artists. Although his tragic death often overshadowed his talents, thousands of drawings and paintings produced and published before his trip to Europe remained, continuing to inspire the marine artists and students of steamboating that followed in his wake. AuthorMark Peckham is a trustee of the Hudson River Maritime Museum and a retiree from the New York State Division for Historic Preservation. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Since the Hudson River was first navigated by steamboats in 1807, there have been hazards- natural and man-made- that have plagued the captains and pilots of these vessels. Fog, low water level, treacherous currents and ice have all taken their toll over the years, as have the occasional cases of inattention to duty, confusing or misunderstood whistle signals between steamers- not to mention fires, boiler explosions or mechanical failure of engine or steering gear. Some of these accidents are well known, such as the loss of the steamer Thomas Cornell when she ran up Danskammer Point, north of Newburgh, in the fog on 27 March 1882 as she was making her regular trip from Rondout to New York. Many years later, the Hudson River Day Line’s flagship Washington Irving was lost as a result of a collision just after she left her pier in New York on 1 June 1926. She was struck on the port side by an oil barge in tow of the tug Thomas E. Moran and sank after she was hurriedly run across the river to shallower water on the New Jersey side. Most of the accidents or incidents have never had the dramatic impact of losses such as that of the Thomas Cornell or Washington Irving. Many of them didn’t result in the loss of the vessel. The Cornell tug G.W. Decker was an example. This small tug was for many years employed as a “helper” tug on Cornell’s tows- picking up or dropping off individual barges at intermediate points on the journey to or from New York. Many years ago, the many brickyards at Haverstraw sent their production to New York on barges, with the helper tug shuttling between the brickyard wharves and the tow. The depth of the river at Haverstraw Bay is not particularly deep, and the fact that the Decker’s bottom plates were eventually found to be very thin was ascribed- in part at least- to the cumulative action of Haverstraw Bay sand on her bottom. We shall never know for sure, but it is a reasonable theory. The river’s depth is very shallow on the wide reaches of Haverstraw Bay outside of the main channel, and on the upper river where dredging had to be accomplished to allow ships to reach the port of Albany. In March 1910, long before the upper river was dredged, the very large and powerful steel-hulled Cornell tug named Cornell- accompanied by her helper Rob- was sent to Albany to break up an enormous ice jam in order that the river might be opened for traffic. It was found that her draft was so great that she grounded from time to time on the northbound trip, but she eventually accomplished her task with no small measure of hazard to Cornell and her crew. It was never attempted again. Over most of the river’s course from New York to the start of the dredged channel north of Hudson the channel is of moderate depth, but in the Highlands- from Peekskill north to Cornwall- there is a lot of water, sometimes extending almost to the shoreline because of the mountainous nature of the area. At Anthony’s Nose, the depth reaches about 90 feet, and under the Bear Mountain Bridge we may find nearly 130 feet of depth. In the region around West Point is where we may find the deepest point on the entire river. Between West Point and Constitution Island, in that part of the river called World’s End, a depth of 202 feet was recorded during one survey many years ago- and that is at mean low water during the lowest river stages. A small steamboat- or “steam yacht” in river parlance- named Carrie A. Ward, built in New Baltimore in 1878, maintained a local service between Newburgh and Peekskill during the 1880s. In late July of 1882, she sank near Cold Spring and was raised. On Saturday, 29 July, she sank for a second time for reasons thus far unknown, again in the vicinity of Cold Spring. By Tuesday, 1 August, she had not been located. The Newburgh Daily Journal reported on that day under the headline “Is She Gone For Good?”: “It is said that the river bed consists of rocks in the locality where she went down, and that the water is of varying depth. It may be fifty [feet] deep in one spot, and nearly twice that a few yards off. Some boatmen have doubts if the Carrie will ever be found. They say she may have settled into a hollow between some of the rocks and her presence may never be discovered.” The situation was not quite as dire as the boatmen predicted. By the next day, she had been located in 60 feet of water. The Journal remarked, “Arrangements are under way to have the yacht raised again.” The Baxter Wrecking Company brought in their divers and equipment on 5 August, and in a short time, the Carrie A. Ward had been raised, repaired and back in service. The Hudson hasn’t always been that kind to its vessels. There have been scores of sail and steamboats, barges and other craft that have sunk in the river never to be raised. We shall unfortunately never know the tales told by their crews. AuthorThis article was originally written by William duBarry Thomas and published in the 2007 Pilot Log. Thank you to Hudson River Maritime Museum volunteer Adam Kaplan for transcribing the article. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

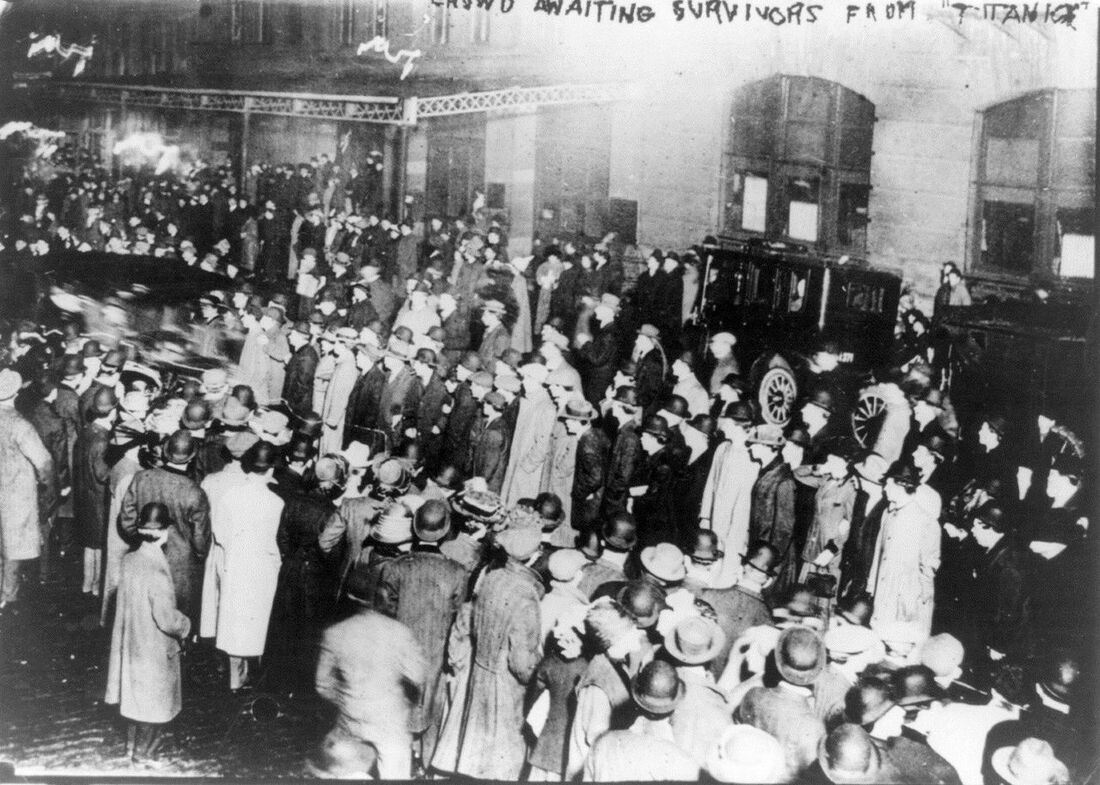

The crowd at the doors of the Cunard Line's Pier 54, where the ship Carpathia had arrived with survivors of the Titanic disaster aboard. The Carpathia arrived in New York in the evening of April 18, 1912; its arrival was delayed due to bad weather at sea. Since there had been many erroneous newspaper stories about the number of those rescued from the Titanic, including one that claimed the ship was damaged and afloat, being towed to Halifax, Nova Scotia, the real extent of the loss of life wasn't evident until the survivors of the disaster arrived in New York. Bain News Service, April 18, 1912. Library of Congress. This week is the anniversary of the sinking of the Titanic. The "unsinkable" vessel struck an iceberg on the evening of April 14, 1912 and was sunk by the morning of April 15, 1912. Of the 2,240 people on board, only 706 were rescued, and were taken aboard the RMS Carpathia. It took several days of bad weather for them to finally reach New York City on April 18, 1912. After dropping off the rescued lifeboats of the Titanic at her original destination - the White Star Line's Pier 59 - the Carpathia docked at Pier 54, of the Cunard Line, to crowds of thousands. To learn more, watch this 100th anniversary special by CNN about the two New York City piers. For more about the Carpathia, a Cunard line transatlantic immigrant vessel, check out this short film about her and her role in the rescue of Titanic survivors. Sadly, the Carpathia was sunk by the U-boat U-55 during the First World War, but nearly all her passengers were rescued. We'll be posting more about the Titanic disaster this week, so stay tuned! If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Welcome to Sail Freighter Fridays! This article is part of a series linked to our new exhibit: "A New Age Of Sail: The History And Future Of Sail Freight In The Hudson Valley," and tells the stories of sailing cargo ships both modern and historical, on the Hudson River and around the world. Anyone interested in how to support Sail Freight should also check out the Conference in November, and the International Windship Association's Decade of Wind Propulsion. The Vermont Sail Freight Project was first conceived of in 2012, and resulted in the launch of the Ceres in mid 2013. Just short of 40 feet long, made of plywood, she had a Yawl rig and leeboards. Leeboards, which are separate drop keels that mount to the sides rather than center of the boat, have been out of use in the US for almost 250 years. Their use aboard Ceres made her very unique looking, and unique to sail as well. With a cargo capacity of only about 10-12 tons, she was not luxurious or large, but she was a capable sailor whose rig could be folded down for passing under the low bridges of the Champlain Canal. She was loosely based on similar sailing canal barges that operated on Lake Champlain and traveled the canal throughout the 19th century. The replica Lake Champlain canal schooner Lois McClure is one example of these historic vessels. Ceres' sailing rig was more inspired by the British sailing barges that operated on the Thames River from the 17th to 20th centuries in England. She was built in the farmyard of the project's founder, Erik Andrus, and launched in Vergennes, VT. After some initial tests, she was used to carry farm produce cargos in 2013 and 2014 from the Champlain Valley to New York City. In 2013, she visited the Hudson River Maritime Museum, hosted a farmer's market with produce from the Champlain Valley, and provided education programs for local school kids. The endeavor gained a lot of press, and was mostly successful, but in the end, the demands of time and attention were too much for a group of volunteers to handle. The project ended in 2014, and Ceres was sold for use as a tiny house in 2018. The rig is still in a barn outside Vergennes, waiting for another boat to be built and launched. Though the project wasn't long-lasting, it was ambitious and brought much-needed attention to the possibilities of sail freight in the US. The Schooner Apollonia was directly inspired by the VSFP, and Maine Sail Freight's single 2015 voyage was in response to the Ceres' precedent as well. Aside from a lot of press coverage and a few sail freight ventures, the VSFP also inspired my Master's Thesis on the revival of Sail Freight and what it would take to make it a reality in the US. Erik Andrus graciously served on the thesis committee for this work, and contributed invaluable insights and materials which will benefit the other efforts which are rebuilding the sail freight economy. You can read more about the Vermont Sail Freight Project here. If you'd like to see some artifacts from the Ceres, there will be a few on display in the exhibit. AuthorSteven Woods is the Solaris and Education coordinator at HRMM. He earned his Master's degree in Resilient and Sustainable Communities at Prescott College, and wrote his thesis on the revival of Sail Freight for supplying the New York Metro Area's food needs. Steven has worked in Museums for over 20 years. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

|

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 [email protected] Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |