History Blog

|

|

|

|

|

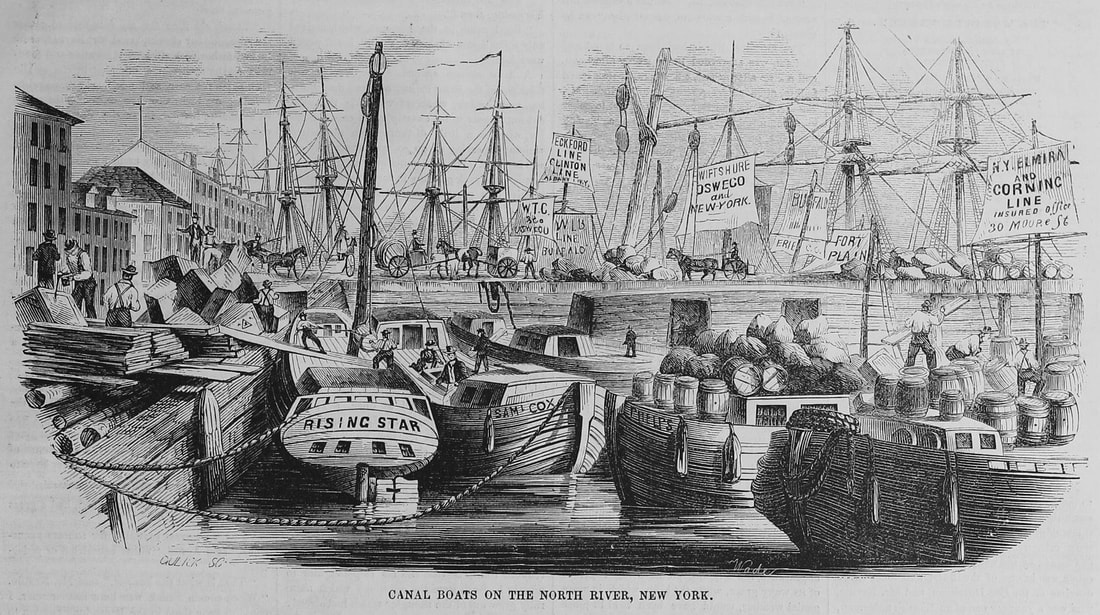

Editor's note: The following excerpts are from the January 3, 1875 issue of the "New York Times". Thank you to Contributing Scholar George A. Thompson for finding and cataloging this article. The language, spelling and grammar of the article reflects the time period when it was written. Loading Her Up. Scenes on the Docks. The Shipping Clerk – The Freight – The Canal-Boat Children. I am seeking information in regard to the late 'longshoremen's strike, and am directed to a certain stevedore. I walk down one of the longest piers on the East River. The wind comes tearing up the river, cold and piercing, and the laboring hands, especially the colored people, who have nothing to do for the nonce, get behind boxes of goods, to keep off the blast, and shiver there. It was damp and foggy a day or so ago, and careful skippers this afternoon have loosened all their light sails, and the canvas flaps and snaps aloft from many a mast-head. I find my stevedore engaged in loading a three-masted schooner, bound for Florida. He imparts to me very little information, and that scarcely of a novel character. "It's busted is the strike," he says. "It was a dreadful stupid business. Men are working now at thirty cents, and glad to get it. It ain't wrong to get all the money you kin for a job, but it's dumb to try putting on the screws at the wrong time. If they had struck in the Spring, when things was being shoved, when the wharves was chock full of sugar and molasses a coming in, and cotton a going out, then there might have been some sense in it. Now the men won't never have a chance of bettering themselves for years. It never was a full-hearted kind of thing at the best. The boys hadn't their souls in it. 'Longshoremen hadn't like factory hands have, any grudge agin their bosses, the stevedore, like bricklayers or masons have on their builders or contractors. Some of the wiser of the hands got to understand that standing off and refusing to load ships was a telling on the trade of the City, and a hurting of the shipping firms along South street. The men was disappointed in course, but they have got over it much more cheerfuller than I thought they would. I never could tell you, Sir, what number of 'longshoremen is natives or aint natives, but I should say nine in ten comes from the old country. I don't want it to happen again, for it cost me a matter of $75, which I aint going to pick up again for many a month." I have gone below in the schooner's hold to have my talk with the stevedore, and now I get on deck again. A young gentleman is acting as receiving clerk, and I watch his movements, and get interested in the cargo of the schooner, which is coming in quite rapidly. The young man, if not surly, is at least uncommunicative. Perhaps it is his nature to be reticent when the thermometer is very low down. I am sure if I was to stay all day on the dock, with that bitter wind blowing, I would snap off the head of anybody who asked me a question which was not pure business. I manager, however, to get along without him. Though the weather is bitter cold, and I am chilled to the marrow, and I notice the young clerk's fingers are so stiff he can hardly sign for his freight, I quaff in my imagination a full beaker of iced soda, for I see discharged before me from numerous drays carboys of vitriol, barrels of soda, casks of bottles, a complicated apparatus for generating carbonic-acid gas – in fact, the whole plant of a soda-water factory. I do not quite as fully appreciate the usefulness of the next load which is dumped on the wharf – eight cases clothes-pins, three boxes wash-boards, one box clothes-wringers. Five crates of stoneware are unloaded, various barrels of mess beef and of coal-oil, and kegs of nails, cases of matches, and barrels of onions. At last there is a real hubbub as some four vans, drawn by lusty horses, drive up laden with brass boiler tubes for some Government steamer under repairs in a Southern navy-yard. The 'longshoremen loading the schooner chaff the drivers of the vans as Uncle Sam's men, and banter them, telling them "to lay hold with a will." The United States employees seem very little desirous of "laying hold with a will," and are superbly haughty and defiantly pompous, and do just as little toward unloading the vans as they possibly can thus standing on their dignity, and assuming a lofty demeanor, the boxes full of heavy brass tubes will not move of their own accord. All of a sudden a dapper little official, fully assuming the dash and elan of the navy, by himself seizes hold of a box with a loading-hook; but having assert himself, and represented his arm of the service, having too scratched his hand slightly with a splinter on one of the boxes, he suddenly subsides and looks on quite composedly while the stevedore and 'longshoreman do all the work. Now I am interested in a wonderful-looking man, in a fur cap, who stalks majestically along the wharf. Certainly he owns, in his own right the half-dozen craft moored alongside of the slip. He has a solemn look, as he lifts one leg over the bulwark of a schooner just in from South America, and gets on board of her. He produces, from a capacious pockets, a canvas bag, with U.S. on it, and draws from it numerous padlocks and a bunch of keys. He is a Custom-house officer. He singles out a padlock, inserts it into a hasp on the end of an iron bar, which secures the after-hatch, snaps it to, gives a long breath which steams in the frosty air, and then proceeds, with solemn mein, to perform the same operation on the forward hatch. Unfortunately, the Government padlock will not fit, and, being a corpulent man, he gets very red in the face as he fumbles and bothers over it. Evidently he does not know what to do. He seems very woebegone and wretched about it, as the cold metal of the iron fastening makes it uncomfortable to handle. Evidently there is some block in the routine, on account of that padlock, furnished by the United States, not adapting itself to the iron fastenings of all hatches. He goes away at last, with a wearied and disconsolate look, evidently agitating in his mind the feasibility of addressing a paper to the Collector of the Port, who is to recommend to Congress the urgency of passing measures enforcing, under due pains and penalties, certain regulations prescribing the exact size of hatch-fastenings on vessels sailing under the United States flag.  "Canal Boats on the North River, New York" by Wade, "Gleason's Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion," December 25, 1852. Note the sail-like signs for various towing lines and destinations, as well as the jumble of lumber and cargo boxes on the pier at left, waiting to be loaded onto the canal boats (or vice versa). I return to my schooner. By this time the wharf is littered with bales of hay, all going to Florida. I wonder whether it is true, as has been asserted, that the hay crop is worth more to the United States than cotton? I think, though, if cotton is king, hay is queen. Now comes an immense case, readily recognized as a piano. I do not sympathize with this instrument. Its destination is somewhere on the St. John's River. Now, evidently the hard mechanical notes of a Steinway or a Chickering must be out of place if resounding through orange groves. A better appreciation of music fitting the locality would have made shipments of mandolins, rechecks, and guitars. Freight drops off now, and comes scattering in with boxes of catsup, canned fruits, and starch. Right on the other side of the dock there is a canal-boat. She has probably brought in her last cargo. And will go over to Brooklyn, where she will stay until navigation opens in the Spring. There is a little curl of smoke coming from the cabin, and presently I see two tiny children – a boy and a girl – look through the minute window of the boat, and they nod their heads and clap their hands in the direction of the shipping clerk. The boy looks lusty and full of health, but the little girl is evidently ailing, for she has her little head bound up in a handkerchief, and she holds her face on one side, as if in pain. The little girl has a pair of scissors, and she cuts in paper a continuous row of gentlemen and ladies, all joining hands in the happiest way, and she sticks them up in the window. This ornamentation, though not lavish, extends quite across the two windows, the cabin is so small. Having a decided fancy, a latent talent, for making cut-paper figures myself, I am quite interested, as is the receiving clerk. I twist up, as well as my very cold fingers will allow, a rooster and a cock-boat out of a piece of paper, and I place them on a post, ballasting my productions with little stones, so that they should not blow away. The children are instantly attracted, and the little boy, a mere baby, stretches out his hands. My attention is called to a dray full of boxes, which are deposited on the wharf for our schooner. Somehow or other the receiving clerk, without my asking him, tells me of his own accord what they contain – camp-stools. I can understand the use of camp-stools in Florida: how the feeble steps of the invalid must be watched, and how, with the first inhalation of the sweet balmy air, bringing life once more to those dear to us, some loving hand must be nigh, to offer promptly rest after fatigue. I return to my post, but alas my rooster and cock-boat have been blown overboard; the wind was too much for them. I kiss my hand to the little girl, who smiles with only one-half of her face; the stiff neck on the other side prevents it. The little boy points to the post and makes signs for more cock-boats. Snow there happens to come along on that wharf an ambulant dealer with a basket containing an immense variety of the most useless articles. He has some of the commonest toys imaginable, selected probably for the meagre purses of those who raise up children on shipboard. There are wooden soldiers, with very round heads but generally irate expressions, and small horses, blood-red, with tow tails and wooden flower-post, with a tuft of blue moss, from which one extraordinary rose blossoms, without a leaf or a thorn on the stem. On that post for ten cents that ambulant toy man put five distinct object of happiness, when the shipping clerk interfered. "It's a swindle, Jacob," he said. That young man was certainly posted in the toy market along the wharves. "You ain't going to sell those things two cents a piece, when they are only a penny? You must be wanting to retire after first of the year. Bring out five more of them things. Three more flower-pots and two more horses. The little girl takes the odd one. What's this doll worth? Ten cents! Give you five. Hand it over. Now clear out. I see you, Sir, watching them children. Poor little mites. No mother, Sir. Father decent kind of fellow; says their ma died this Spring. Has to bring 'em up himself, and is forced to leave them most all day. He is only a deck-hand and will be the boat-keeper during Winter. Been noticing them babies ever since I have been loading the schooner – most a week – and been a wanting to do something for their New-Year's. A case of mixed candies busted yesterday, and they got some. They have been at the window ever since, expecting more; but nothing busted. You can't get in; the cabin is locked, but I can manage it through the window." So my young friend climbed on board, with the toys in his pocket, lifted up the sash, and passed through the toys one by one, the especial rights of proprietorship having been carefully enjoined. Presently all the soldiers and the follower-pots were stuck in the window, and the little girl was hugging the doll. "Loading her up; taking in freight for a vessel of a Winter's day on a wharf isn't fun," said the young gentlemen sententiously. "I shouldn't think it was," I replied. "In fact, there ain't much of anything to see or do on a wharf which is interesting to a stranger." "You are from the country, ain't you?" asked the young man with a smile. "Never seen New-York before? Wish you a happy New Year, anyhow." I did not exactly how there could be any reservation as to wishing me a happy New Year whether I was from the country or not, but supposing that this singularity of expression arose from the general character of the young man, or because he was uncomfortable from the frosty weather, I returned the compliment, inquiring "whether a stiff neck was not very hard on children," and not being a family man, added, "They all get it sometimes, and get over it, don't they ?" "It ain't a stiff neck, it's mumps. Mother sent me a bottle of stuff for the child three days ago, and her father has been rubbing it on, and she's most over it now. When I was a little boy," added the clerk reflectively, "toys cured most everything as was the matter with me." "Just my case," I replied, as we shook hands and I left the wharf. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

0 Comments

Welcome to Sail Freighter Fridays! This article is part of a series linked to our new exhibit: "A New Age Of Sail: The History And Future Of Sail Freight In The Hudson Valley," and tells the stories of sailing cargo ships both modern and historical, on the Hudson River and around the world. Anyone interested in how to support Sail Freight should also check out the Conference in November, and the International Windship Association's Decade of Wind Propulsion. The Schooner Wyoming was built at the Percy and Small Shipyard in Bath, Maine, in 1909, becoming the largest wooden ship ever built. An engineless 6-masted schooner, she carried almost 40,000 square feet of sail, with a crew of only 16 to move up to 6,000 tons of coal at a time. Wyoming was launched at the tail end of the Windjammer era, and was adapted for moving fossil fuels in the form of Coal. These types of bulk cargoes, for fueling cities, railroads, and steamships were the last cargo carried in large volumes by the Windjammers, and generally proved economically viable into the 1920s. However, the only way to maintain that economic competition was to get ever larger and use fewer and fewer crew to get the job done. To bring crew numbers down to the remarkably low number of 16, the Wyoming had mechanical winches for the running rigging such as sheets and halyards, run by a steam powered Donkey Engine, which also powered the pumps and anchor windlass. Although originally intended for coastal trade as a Collier, Wyoming also crossed the Atlantic during the First World War, surviving the U-Boat menace which devastated the Atlantic Windjammer fleet at the time. She returned to US coastal trade after the war, and was in service moving coal until she foundered in a Nor'easter off the Massachusetts coast in 1924. Wyoming is important because of her late date of construction and the innovations built in for conserving crew. She is a good example of the type of ship which was able to compete not on speed, but cost in an era of increasingly inexpensive steam propulsion: Fore-And-Aft rigged, partly automated, and designed for a low crew requirement, she was also built for bulk cargo which did not rely on speed for its value. Such ships would be built into the 1920s, before the economic situation for shipping started to decline and hundreds of vessels were laid up and out of use due to a reduction in international shipping, and the expansion of railroads took over from the coastal shipping trade. For more information on the Wyoming and the other Schooners launched by Percy and Small, you can visit the Maine Maritime Museum in Bath, Maine, or pick up a copy of "A Shipyard In Maine" by Ralph Linwood Snow and Douglas K Lee. AuthorSteven Woods is the Solaris and Education coordinator at HRMM. He earned his Master's degree in Resilient and Sustainable Communities at Prescott College, and wrote his thesis on the revival of Sail Freight for supplying the New York Metro Area's food needs. Steven has worked in Museums for over 20 years. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Welcome to Sail Freighter Fridays! This article is part of a series linked to our new exhibit: "A New Age Of Sail: The History And Future Of Sail Freight In The Hudson Valley," and tells the stories of sailing cargo ships both modern and historical, on the Hudson River and around the world. Anyone interested in how to support Sail Freight should also check out the Conference in November, and the International Windship Association's Decade of Wind Propulsion. The Thomas W Lawson was the largest schooner ever built, at some 475 feet long and 5200 Gross Register Tons. She was made of steel, sported no engines, and had seven masts, one of the very few seven-masted schooners ever built. Launched in 1902, she started her career as a Collier, but was converted to an oil tanker in 1906, serving mostly on the US East Coast. After her retrofit to a tanker, she was one of the few sailing tankers ever in service. Like the slightly smaller Wyoming, the Lawson had modern winches, a donkey engine, and a small crew of only 18. With seven masts and only so much sail possible at a time, the Lawson was very much at the point of being too large to sail with the technology of the time: In GRT and displacement terms she was bigger than the Preussen, but carried only about two thirds the sail area. This made her ungainly to maneuver, and she was too deep of draft to enter many east coast ports. The Lawson did not have a long career. After launching in 1902, she served as a collier, though not at maximum profitability due to the small number of ports she could access. On a trip to London in 1907 she was wrecked in a gale off the Scilly Islands near the coast of Cornwall. This wreck caused the first large marine oil spill, and killed 16 out of the 18 crew. While the Lawson's story is mostly one of costly mistakes, it shows one of the same problems as the Preussen: You can only make a sailing vessel so large before it becomes hazardous to operate. While modern technology may increase the size of possible sailing vessels, these warnings from the past should be kept in mind for future windjammer developments. AuthorSteven Woods is the Solaris and Education coordinator at HRMM. He earned his Master's degree in Resilient and Sustainable Communities at Prescott College, and wrote his thesis on the revival of Sail Freight for supplying the New York Metro Area's food needs. Steven has worked in Museums for over 20 years. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Welcome to Sail Freighter Fridays! This article is part of a series linked to our new exhibit: "A New Age Of Sail: The History And Future Of Sail Freight In The Hudson Valley," and tells the stories of sailing cargo ships both modern and historical, on the Hudson River and around the world. Anyone interested in how to support Sail Freight should also check out the Conference in November, and the International Windship Association's Decade of Wind Propulsion. NOTE: This week we have a guest post from the San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park about the Schooner C A Thayer a uniquely West Coast sail freighter. You can find more on their website. How often do we hear phrases such as “The last of its kind” or “One of a kind”? With a cultural resource, how or should we evaluate the value of such a statement? And what constitutes the truth of such a statement? Built in 1895, the C.A. Thayer is a bald-headed, three-masted West Coast lumber schooner, and yes… she is the last of her kind. Constructed in the yard of Hans Bendixson in Fairhaven, California (near Eureka, in the far northwestern part of California), she is both typical and atypical. She is typical in that she was a common type of vessel built for lumber service on the U.S. West Coast. She is atypical in that she survives when hundreds of her kin have rotted away or were otherwise lost. Vessels with her hull and elements of her rigging design were not to be found anywhere else in the country, and these elements, though not solely responsible, played a key role in the decision for a rebuilding that has left her in practically new condition. She was, in fact, a highly specialized West Coast maritime product, designed for both the environment in which she was meant to sail and the cargo she was meant to haul. With lumber hauling along the West Coast as her intended mission, the design of the Thayer reflects the contours of the West Coast as well as economy. Large, protected harbors such as San Francisco Bay are rare along the western seaboard. The majority of the California coast is a sailor’s nightmare. Whereas San Francisco Bay is a large and sheltering anchorage, most of the coast is rocky with many cliffs, and exposed. Big Sur, south of San Francisco, is majestic, beautiful, and breathtaking… if you are on shore looking out to the ocean. But upon the deck of an engineless sailing vessel, it could be completely frightening. And if wrecked, there are no obvious ways to get safely ashore. So, it was wise to have a handy maneuverable rig. Thus, the fore and aft schooner rig was very popular, especially for the trip north into the prevailing wind and ocean currents. As this rig evolved on the West Coast, the bald-headed schooner became common, particularly in three masted designs, in which there were no separately attached topmasts. Given the tall Pacific lumber available for mast timbers, this simplified her sail and rigging arrangement. On occasion, one might also see a peculiar sail addition. This was the West Coast square sail (and sometimes surmounted by a raffee). Found on the forward mast, a yard was crossed and so arranged that a sail could be laterally set on one or the other side. So, instead of setting this square sail from the top down, it was set from the center line of the vessel outboard, one side at a time, since the foresail would block the wind of the other/leeward side. The Thayer did not carry such a sail for most of her career, but is documented as carrying one during some of her voyages south to Australia, so as to take better advantage of any following winds on the long trans-Pacific voyage. Combine all of the above with a steam donkey engine (not something unique to the West Coast) mounted within the deckhouse, the primary sails could be made in incredibly large size, yet the vessel sailed with a small, and a correspondingly cheaper to employ, crew. This engine, therefore, had the same effect that automation technology does today, and allowed the C.A. Thayer to be sailed with as few as eight crew members: four sailors, one cook, two mates, and a Captain. The Columbia River in Oregon, the site of many of the Douglas Fir loading ports, influenced the Thayer’s hull form. A ship with a single deck and relatively flat bottom was what was called for. The C.A. Thayer and the rest of her West Coast kin had to be built to pass safely over the sand bars at the mouths of such rivers. Though not explicitly flat-bottomed herself, the Thayer has very little dead rise and is much wider (36’4”) than she is deep (11’8”). One result of this shallowness is that about half her load of 575,000 board feet of lumber was stacked up on deck. Due to this, there was a second set of pin rails mounted high on her shrouds to provide accessible belaying points for her running rigging when a full load was carried. The sailors merely used the deck load top as a line handling deck. But with the resulting broad beam and shallow depth of hold, she was able to safely mount the sand bars. This hull design, incidentally, also provided stability when sailing empty. When northbound, it was often unnecessary to load ballast. The building material with which all this was achieved was the same as that which most often formed her cargo, old growth Douglas fir. Given her wide beam, but shallow depth of hold, her upper ceiling planking played a critical role is resisting hogging tendencies. Therefore, when visiting the vessel and entering her hold, one can spy individual planking 8 inches thick and up to a shocking 80 feet long. Her clamps too are of major size, though her restoration team was unable to obtain pieces of original (10 inches thick and 110 feet in length) size. Due to her being designed for immense deck loads, her hanging knees, supporting her deck, are huge and especially interesting as they cannot be cut to shape. To have the necessary strength to support deck loaded lumber cargoes, they have to be of a naturally curved grown shape. This was a particular challenge, especially when considering the lack of natural curves in Douglass Fir. In other parts of the country where other types of trees were more common, these natural curves (referred to as compass timber) were often acquired where large branches grew in a curving outward arc from the trunk. With Douglas Fir trees, branches grow out from the trunk at nearly 90 degrees. So in order to get the natural curved shape needed, effort was made to make use of the stumps and roots of the tree. In particular from trees that grew on the side of a hill where the curving roots would have an especially sharp angle. Though not unique along the West Coast, there were many features that made these ships totally distinctive compared to the Gulf Coast, East Coast, or Great Lakes practices. These design features, and the fact that she is now the last of her kind, were important factors why the decision was made to proceed with her massive reconstruction. Today, the C.A. Thayer has a largely “new ship” feel about her. Though longevity is something all wooden structures aspire to, wooden vessels/ships, given the marine environment they live in, are particularly vulnerable to entropy. With her reconstruction now nearly complete, visitors will have access to a unique West Coast historic maritime resource for a long time to come. Bibliographic References Books: Olmsted, Roger. C.A.Thayer and the Pacific Lumber Schooners. Los Angeles: Ward Ritchie Press, 1972. Unpublished Works: Cleveland, Ron. The Rigging of West Coast Barkentines & Schooners. Unpublished manuscript, Maritime Research Center, San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park, no date. Myers, Mark Richard. “Pacific Coast-Built Sailing Ship Types: 1840-1921.” B.A. Honors Study Thesis, Pomona College, 1967. Official Reports: Architectural Resources Group. “Historic Structure Report: Schooner C.A. Thayer.” National Park Service, San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park, 2022. Delgado, James P. & Gordon S. Chappell. “National Register of Historic Places Inventory, Nomination Form: C.A.Thayer (Schooner).” National Park Service, Western Region, 30 June 1978. Periodicals: Andersen, Courtney J. “Exciting Times in the Life of C.A. Thayer. Re-rigging and Old Sailing Ship: A Maritime Detective Story.” Sea Letter 72 (Fall 2015), 2-12. Canright, Stephen. “Born of the Lumber Trade: An Historical Context for the C.A. Thayer.” Sea Letter 50 (Summer 1995), 3-11. Canright, Stephen. “Preserving the C.A. Thayer: What is to be Done?” Sea Letter 50 (Summer 1995), 20-25. Canright, Stephen. “Rebuilding the C.A. Thayer.” Sea Letter (Summer 2007), 6-24. Cox, Thomas R. “William Kyle & the Pacific Lumber Trade: A Study in Marginality.” Journal of Forest History 19:1 (January 1975), 4-14. Cox, Thomas R. “Single Decks and Flat Bottoms: Building the West Coast’s Lumber Fleet, 1850-1929.” Journal of the West XX: 3 (July 1981), 65-74. Dennis, D.L. “Square Sails of American Schooners.” The Mariner’s Mirror 49: 3 (August 1963), 226-227. McDonald, Captain P.A. “Square Sails and Raffees.” The American Neptune V (1945), 142-145. Miles, Ted. “The Later Lives of the C.A.Thayer.” Sea Letter 50 (Summer 1995), 13-19. AuthorChristopher Edwards is a National Park Ranger at San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

In May of 2022, the Hudson River Maritime Museum will be running a Grain Race in cooperation with the Schooner Apollonia, The Northeast Grainshed Alliance, and the Center for Post Carbon Logistics. Anyone interested in the race can find out more here. This May, the Northeast Grain Race spanned the Hudson Valley: Two vehicles entered with impressive scores for each, pitting Solar against Wind power. There were far more shipments, and we'll get to those shortly. First, let's take a look at the shipments: Solar Sal Boats entered a cargo in the Micro Category of 550 pounds of flour and grains from Ithaca Mills, which they brought to the People's Place in Kingston. They picked up the grains with an electric car which was charged by an off-grid solar array, then transferred the load to a Solar Sal 24 solar boat at Waterford, NY. Then, down the canal and river they came to Kingston, docked at the HRMM docks, and unloaded to another electric car. This is when things get really great for this particular delivery: While the car was parked and the boat at the dock, there was some time before the stated delivery needed to arrive, so the car was plugged into the solar array of the boat. By the time they departed to make the final 2 miles of delivery, the car was charged enough to make it at least that far on just the boat's contribution. Everything about the entry was completely solar powered, and off grid, so no points were lost to fuel or energy use. Thank you to Dr. Borton of Solar Sal Boats for the video. The second entry was by Schooner Apollonia, running their usual May cargo run full of Malt and Flour. Technically, this was a few different entries spanning from Hudson NY to New York City, and used a similar combination of vehicles and methods. The Malt they carried was from Hudson Valley Malt, in Germantown, and moved to the docks with a vegetable oil powered truck. Then, of course, the Apollonia sailed the entries south, delivering the last mile by solar-charged cargo bike. The flour they carried was from Wild Hive flour, and made it to the dock in an electric car charged at the farm's off-grid solar power system. The flour was only about 425 pounds in total, but there were over three tons of malt on board. The malt and flour got dropped off at various locations, making score calculations complex, but the impressively low use of the engines on Apollonia meant points against for fuel use were minimal: The engine only got used for 105 minutes, and burned under 2 gallons of fuel. In total, there were 7 entries onboard Apollonia. Now to the big question: Who won? For the Micro Category: Solar Sal Boats, Ithaca Mills, and The People's Place, with 21.5 points. For the ½ TEU Category: Schooner Apollonia, Hudson Valley Malt, and Sing Sing Kill Brewery, with 212.5 points. Overall, Apollonia wracked up 245 points, an impressive score to beat next year. The ingenuity of the Solar Sal entry in using a solar boat to charge an electric car sets the bar high for future competitors, and even points out another use for solar boats and vehicles which I don't think has been looked at very closely thus far: How they can directly contribute to balancing each other's energy needs. Planning for next year's Grain Race is underway, and I'm looking forward to more entries and greater ambitions in the coming year. Until then, keep an eye out for more developments on Sail Freight, Sustainability, Resilience, and Climate Change here at the Hudson River Maritime Museum. AuthorSteven Woods is the Solaris and Education coordinator at HRMM. He earned his Master's degree in Resilient and Sustainable Communities at Prescott College, and wrote his thesis on the revival of Sail Freight for supplying the New York Metro Area's food needs. Steven has worked in Museums for over 20 years. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Welcome to Sail Freighter Friday! This article is part of a series linked to our new exhibit: "A New Age Of Sail: The History And Future Of Sail Freight In The Hudson Valley," and tracks sailing cargo ships both modern and historical. Anyone interested in how to support Sail Freight should also check out the Conference in November, and the International Windship Association's Decade of Wind Propulsion. Schooner Apollonia is one of our favorite Sail Freighters, because she's on the Hudson River right now. She has been carrying cargo for two years now, with a bit of a preview season in 2020, testing out cargos and becoming familiar with regional waterfront infrastructure. Apollonia is currently the only active sail freighter in the US. Apollonia is a 64' steel schooner built in Baltimore in 1946. Designed to carry cargo or operate as a pleasure yacht, she was purchased on Craigslist after spending 30 years on the hard and refitted as a cargo vessel. She was under restoration for four years before arriving at the Hudson River Maritime Museum in the fall of 2019 to build wooden blocks as she built out her full rigging. Her first official season was in 2021, when the vessel made 55 port calls at 15 ports on the Hudson River and in New York Harbor. Today she is homeported in Hudson NY, and often visits the Hudson River Maritime Museum docks as she works to connect the Hudson Valley and New York City. Captained by Sam Merrett, Apollonia carries a lot of malted grain for breweries as the main part of her cargo, but she also carries almost anything else: Solar panels, cider, hot sauce, beer, coffee, maple syrup, flour, honey, yarn, apparel, books, vegetables, red oak logs for a mushroom farm, were all on the list in 2021, and more will be involved in 2022. She can carry 10 tons (20,000 lbs) of cargo at a time, up to 600 cubic feet. Apollonia is a critical link in relearning the craft and trade of working sail. Inspired by the Vermont Sail Freight Project's Ceres, the project is a combination of sail freight and localized food economy with many educational side benefits. Apollonia builds connections between people and the river, as well as between businesses shipping goods sustainably by wind power, with first- and last-mile on-shore aspects done with a solar-powered cargo bike and trailer. You can find out more about the Apollonia's Impacts from the 2021 season here, and check out her schedule and cargos for 2022 - and get involved as a "Shore Angel" or sail freight customer - at her website. If you find her at the docks anywhere on her route this season (there's a tracker on the website), she has a mobile component of our new exhibit aboard, which is worth checking out. Apollonia is also partnering with the Museum for the Northeast Grain Race and the Sail Freight Conference in November. AuthorSteven Woods is the Solaris and Education coordinator at HRMM. He earned his Master's degree in Resilient and Sustainable Communities at Prescott College, and wrote his thesis on the revival of Sail Freight for supplying the New York Metro Area's food needs. Steven has worked in Museums for over 20 years. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

We have been talking a lot about Sail Freight recently, with the upcoming exhibit "A New Age Of Sail: The History And Future Of Sail Freight On The Hudson River," the Northeast Grain Race happening in May, and the Conference scheduled for November. It isn't always clear what the real-world gains would be in terms of carbon impact, or what speeds might look like in a sail freight future. Very few people have studied sail freight with anything but a historical lens, and even fewer are actually running sail freighters. Those who are running them are far too busy doing so to make an academic study of their results. This recently changed with the publication of "Operation of a Sail Freighter on the Hudson River: Schooner Apollonia in 2021" in the Journal of Merchant Ship Wind Energy. This paper is especially interesting to those along the Hudson River and New York Harbor, as it focuses on the Schooner Apollonia, our regional sail freighter out of Hudson, NY. Captain Merrett and I learned a lot in the course of writing the paper. Apollonia moved over 27 tons of cargo, and only used 19.47 gallons of fuel over 6 months. If measured the same way as truck efficiency normally is, then Apollonia would be 25% more efficient than railroads, and 9 times more fuel efficient than average trucks. She prevented at least 1,500 pounds of CO2 from being emitted by trucks. The speed of Sail Freight is another thing we learned more about. Since Apollonia sits at anchor when the tide is against her, just like the Hudson River Sloops and Schooners of the past, she only made an average speed on course of 1.578 knots if you include time at anchor. Because she had to tack and jibe, she sailed as fast as 8 knots over the course of the season, but made an average speed on course of 2.5 or so knots when she wasn't at anchor. The article also gives an account of what cargo was moved, the ports called at, and technical details of Apollonia's 2021 season. If you wanted to get an idea of how much malt she moved, or what other cargo she carried, the paper has those details on pages 4-5, while other voyage data is on page 6. Lastly, I'd like to leave you with this quote from page 9, which I believe is worth thinking about as we move into an era which will most likely be defined by high energy prices and fuel shortages: "If fuel were allocated to vehicles based solely on their maximum theoretical fuel efficiency, no cargo moved by fossil fuels or electrified transport would ever arrive on target…By contrast, 5,000 years of precedent has shown a lack of fuel does not fundamentally affect sail freighters' ability to reach their destination." AuthorSteven Woods is the Solaris and Education coordinator at HRMM. He earned his Master's degree in Resilient and Sustainable Communities at Prescott College, and wrote his thesis on the revival of Sail Freight for supplying the New York Metro Area's food needs. Steven has worked in Museums for over 20 years. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today

Twenty-seven years ago, the remains of two Hudson River schooners were identified at a remote dock where they were abandoned in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century. Historic photographs of the schooners from 1914 and 1918 were located offering detailed information about their layout and rig. The New York State Division for Historic Preservation and Grossman and Associates Archaeology digitally recorded the more intact of the two hull bottoms producing photographs and a plan drawing. An article describing this project and summarizing the historic context of Hudson River sloops and schooners appeared in Sea History No. 77, Spring, 1996. The Hudson River was New York’s “Main Street” for at least 200 years and sloops and schooners were the principle vehicles of its commerce. Even after the Age of Steam dawned in 1807, these boats continued to evolve and improve through the introduction of centerboards, greater carrying capacity and changes in working equipment. The last generation of these boats soldiered on until the end of the nineteenth century carrying bulk freights such as iron ore, sand and bricks. Their graceful movements and white sails were often captured by the artists of the Hudson River School and nostalgia for these quiet, powerful and non-polluting boats led to the construction of the Clearwater, a modified replica of a mid-nineteenth century example, launched in 1969. Since this effort, more has been learned about the Hudson’s sloops and schooners. Intact examples with preserved decks, bowsprits, and in some cases deck cargos have been discovered well below the river’s surface through remote sensing technologies and diver surveys. Nevertheless, the schooners studied in 1993 revealed important details about the framing and configuration of these regionally significant boats not available in the sparse written record. We observed that the centerboards were placed on one or the other side of the keel so as not to weaken the backbone of these boats. To counteract the added weight on one side, we found that the mainmast of one was stepped off center on the opposite side. We also found evidence in the more intact hull of added frames and riders used ostensibly to reinforce an aging hull for continuing service. There was some evidence to suggest that the more intact hull was built as a single-masted sloop and later re-rigged with two masts as a schooner at a time when this was done to reduce crews in the face of rising labor costs. Carla Lesh, Collections Manager and Digital Archivist of the Hudson River Maritime Museum and I visited the site at low tide several days ago. Ice and debris have demolished the more lightly framed of the two schooners but the one that was carefully recorded thankfully remains much as it did in 1993. The site is located on public land and protected under state and federal statute. Should you encounter this or other historic wreck sites, please refrain from disturbing them in any way. They are important touchstones of our maritime heritage and can still answer questions about our past that cannot be answered in the written record. AuthorMark Peckham is a trustee of the Hudson River Maritime Museum and a retiree from the New York State Division for Historic Preservation. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

|

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 [email protected] Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |