History Blog

|

|

|

|

|

As important to the Hudson River’s transportation infrastructure as the express steamers that plied from major towns and cities to New York were the local steamboats- called yachts- which connected many otherwise unreachable riverside villages with these major localities. They were the buses- the “jitneys”- of a bygone era. These local routes were the lifeblood of the villages, which were isolated from the centers of commerce like Newburgh, Poughkeepsie, Rondout, Hudson and Albany, and too small to merit a landing by the larger steamers. The yachts provided a means by which residents of the outlying points might reach a nearby large town, for business or pleasure, in the days before there were convenient railroad connections or improved roads. The little steamers also carried all kinds of local freight, in particular the farm produce necessary to feed those who lived in town, as well as the local newspapers which were so important in those days before radio and television. The yachts were small propeller steamboats carrying a modest number of passengers. They were varied in their design- some were single-decked while larger vessels might have an upper deck- ideal for a moonlight sail on a summer evening. Typically they were from 50 to 100 feet in length, and were propelled by small steam engines. The operating crew might consist of a captain, engineer and a deckhand or two, depending on size. Some of the larger yachts might also carry a fireman. Rondout was the base of operations for the yachts that operated up the river to Glasco and Malden, down river to Poughkeepsie, and along the Rondout Creek on which one could venture as far as Eddyville with way landings at South Rondout and Wilbur. At Rondout, vessels like Augustus S. Phillips, Charles A. Schultz, Charles T. Coutant, Edwin B. Gardner, Eltinge Anderson, Ettie Wright, Glenerie (later Elihu Bunker), Henry A. Haber, Hudson Taylor, John McCausland, Lewis D. Black, Lotto, Morris Block (later Kingston), Thomas Miller, Jr. and others maintained the local services over the years, providing for the transportation needs of many residents and businesses along the creek and in the small riverside villages. In addition, smaller vessels named Annex and Minnie ran from Eddyville up the D. & H. Canal as far as Creek Locks. The upriver towns of Coeymans, Coxsackie, New Baltimore and other points were way landings on a web of routes between Hudson and Albany and on to Troy. The steamers of the Albany and Troy line were particularly busy. Similar routes were maintained out of Newburgh and other down river locations. From Newburgh, one could travel to Peekskill on the little Carrie A. Ward or to Wappingers Falls aboard Messenger. A trip from Wappingers Falls to Newburgh was a challenge if Captain Terwilliger’s steamer was not running. The traveler had to make his way to New Hamburgh by stage or carriage, then by train to Fishkill Landing, then on to Newburgh by ferry- all of course depending on the vagaries of travel in those far-off days. The yachts maintained a fixed schedule during the months when the river was free of ice. During their off hours they might be chartered for an excursion by a local organization like a volunteer firemen’s association. A popular Sunday afternoon destination of the Rondout Creek boats was Henry A. Haber’s recreational park near Eddyville. This gentleman’s entrepreneurial nature was evident to the pleasure seekers- Haber yachts carried them to the Haber park and back. It was not always a world of easy-going transportation, but accidents were rare. Fog, high winds, floating ice or some other hazard occasionally made a trip exciting. On the morning of April 8, 1901, the Rondout-to-Glasco yacht John McCausland collided with her running mate Glenerie at the mouth of the Rondout Creek. McCausland, outward bound for Glasco, was not badly damaged, but Glenerie, headed for home to Rondout, was not so fortunate. She began to fill with water, and Cornell tugs, quick on the scene, succeeded in moving the partly sunken yacht to a nearby sand bar. Even today, the eddies that occur at the mouth of the creek at certain stages of the tide can be dangerous for small craft, and it was claimed that the stern of the Glenerie- perhaps encountering her own Charybdis- swung into the path of the other vessel as they approached one another. It was clearly a case of being in the wrong place at the wrong time. The following day, Glenerie was raised and taken to Hiltebrant’s yard for repairs. The little yacht was back in service on the 20th- twelve days after the accident. Nobody aboard either steamer was injured. With the construction of paved roads and the introduction of the bus and the motor car for transportation from the 1910s, the era of “jitneys on the river” came to a close. One by one, the yachts were dismantled or otherwise left the routes over which they had been so much a part of life along the Hudson. No longer would the daily routine at the riverside villages be punctuated by the whistles of the yachts as they made their frequent landings. Progress caused life to be easier in a way, but some of the joy of travel on the river disappeared with the yachts. AuthorThis article was written by HRMM Curator Emerita Allynne Lange and originally published in the 2002 Pilot Log. Thank you to Hudson River Maritime Museum volunteer Adam Kaplan for transcribing the article. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

0 Comments

“The maintenance of a merchant marine is of the utmost importance for national defense and the service of our commerce.” President Calvin Coolidge “In peacetime, the U.S. Merchant Marine includes all of the privately owned and operated vessels flying the American flag – passenger ships, freighters, tankers, tugs, and a wide miscellany of other craft. Merchant Marine vessels ply the high seas, the Great Lakes, and the inland waters, such as the Chesapeake Bay and navigable rivers.” Heroes in Dungarees by John Bunker During the colonial period, businessmen and legislators realized that prosperity was connected to trade. The more shipment of imports and exports through colonial ports the more money there was to be made. Carrying American produced goods to market in American made and managed ships kept the money in American pockets. Formation of the United States Merchant Marine is dated to 1775 when citizens at Machias, Massachusetts (now Maine) seized the British schooner HMS Margaretta in response to receiving word of the Battles of Lexington and Concord. After the Revolutionary War American ships were no longer under the protection of the British empire. The new nation offered incentives for goods to be moved on American ships. Wars on the European continent turned attention away from American activity as U.S. ships opened up new trade routes in the early Federal period. The Empress of China reached China in 1784, the first U.S. registered ship to do so. American shipping and shipbuilding flourished in the early 1800s. The years between the War of 1812 and the Civil War saw the development of canal systems connect the western interior with seaport markets. “Those years saw the merchant marine rise to its zenith in terms of the percentage of American trade carried. Only in the aftermaths of World Wars I and II would its percentage of world tonnage stand as high.” America's Maritime Legacy by Robert A. Kilmarx Sail powered packet ships, carrying passengers, pushed their crews hard. There was money to be made in quick passages across to Europe and back. Clipper ships also relied on speed as they carried high value cargoes of silk, spices and tea across the Pacific and the slave trade across the Atlantic. The hybrid sailing ship/sidewheeler steamer Savannah’s 1819 Atlantic crossing, the first with a steam powered engine, signaled the start of the transition from sail to steam. The May 22 date for National Maritime Day commemorates the day Savannah set sail from Savannah, Georgia to England. The Savannah transported both passengers and cargo. More information about the SS Savannah is here: Restoration of the merchant marine after the disruption of the Civil War was a national political issue in 1872. The Republican party advocated adopting measures to restore American commerce and shipbuilding. Mail packets, carrying mail around the world were active in this period. Financial scandals were associated with mail packet contracts. Training sailors in an academic setting began in the last quarter of the 1800s, predecessors of the present day Maritime Academies. The period between the end of the Civil War in 1865 and the European outbreak of World War I was a dynamic time for shipping. American raw materials and agricultural products were shipped to world markets and products from those markets received and used by American industries. John Bunker writes: “When we entered the war, the Merchant Marine, although still privately owned, came under government control. The men who sailed the ships were civilians, but they also were under government control and subject to disciplinary action by the U.S. Coast Guard and, when overseas, by local U.S. military authorities. Compared with soldiers and sailors, merchant seaman had much more freedom of movement. After completing a voyage, they could usually leave a ship but had to join another vessel within a reasonable period of time or be drafted into the U.S. Armed Forces. There was no uniform required for merchant seamen. Some officers wore uniforms; many did not. During the war, merchant ships were operated by some forty steamship companies, and the War Shipping Administration assigned new ships to them as they were completed. A total of 733 U.S.-flag merchant ships were lost during World War II. More than 6,000 merchant seamen died as the result of enemy action.”p12 U.S. Maritime Service personnel operated the 2,700 Liberty ships during World War II. The U.S. Maritime Service was the only service at the time with African American crew members serving in every capacity aboard ship. Seventeen Liberty Ships were named for African-Americans. Approximately 10%, 24,000, African Americans served in the Merchant Marine during World War II. During World War II the U.S. Merchant Marines moved war personnel and material under conditions shown above. The American Merchant Mariner’s memorial in Battery Park, New York City reads: "This memorial serves as a marker for America’s merchant mariners resting in the unmarked ocean depths." Poignantly the sailor in the water is covered twice a day at high tide. Installed in 1991 by sculptor Marisol Escobar designed based on a photo of the sinking of the SS Muskogee by German U-boat 123 on March 22nd, 1942. The photo was taken by the U-boat captain. The American crew all died at sea. Merchant mariners who served in World War II were denied veterans recognition and benefits including the GI Bill. This despite having suffered a per capita casualty rate greater then those of the U.S. Armed Forces. In 1988 a federal court order granted veteran status to merchant mariners who participated in World War II. On May 31, 1993, the Hudson River Maritime Museum received a brass plaque reading: “The United States Merchant Marine. This plaque is dedicated in memory of those who served in the U.S. Merchant Marine during W.W. II and in particular to those who did not survive “The Battle of the Atlantic”. Their dedication, deeds and sacrifices while transporting war material to the war shared their sacrifices and final victory, we, their surviving shipmates dedicate this memorial with the promise that they shall not be forgotten. Died 6,834. Wounded 11,000. Ship Sunk 833. P.O.W. 604. Died in Prisoner of War Camps 61. American Merchant Marine Veterans – May 31, 1993.” Today, the Maritime Administration (MARAD) is the Department of Transportation agency responsible for the U.S. waterborne transportation system. Founded in 1950 the mission of MARAD is to foster, promote and develop the maritime industry of the United States to meet the nation’s economic and security needs. MARAD maintains the Ready Reserve Fleet, a fleet of cargo ships in reserve to provide surge sea-lift during war and national emergencies. A predecessor of the RRF, the Hudson River Reserve Fleet of World War II ships, popularly referred to as the Ghost Fleet, was in the Jones Point area from 1946 to 1971. More about the Maritime Administration including a Vessel History Database can be found here: https://www.maritime.dot.gov/ United States Merchant Marine TrainingModern day training of merchant marines is held at seven academies, two of which U.S. Merchant Marine Academy and SUNY Maritime College, are in New York State. The U.S. Merchant Marine Academy, Kings Point, NY (USMMA) is one of the five United States service academies. When the academy was dedicated on 30 September 1943, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, noted "the Academy serves the Merchant Marine as West Point serves the Army and Annapolis the Navy." USMMA graduates earn:

USMMA graduates fulfill their service obligations on their own, providing annual proof of employment in a wide variety of MARAD approved occupations. Either as active duty officers in any branch of the military or uniformed services, including the Public Health Service and the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration or entering the civilian work force in the maritime industry. State-supported maritime colleges: There are six state-supported maritime colleges. These graduates earn appropriate licenses from the U.S. Coast Guard and/or U.S. Merchant Marine. They have the opportunity to participate in a commissioning program, but do not receive an immediate commission as an Officer within a service. More information about the U.S. Merchant Marines can be found here:

If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

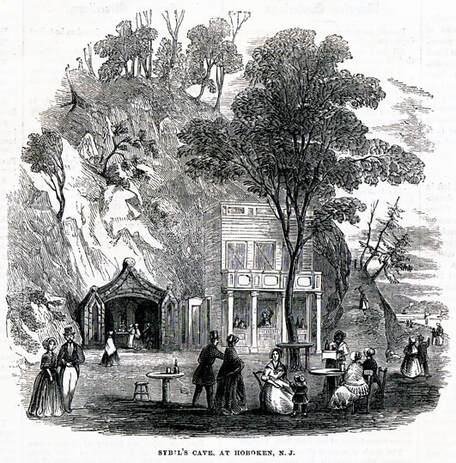

Editor's note: The following text is an except from "Fifteen Minutes around New York" by George G. Foster, published by DeWitt & Davenport, New York circa 1854, pages 52-54. Thank you to Contributing Scholar George A. Thompson for finding, cataloging and transcribing this article. The language, spelling and grammar of the article reflects the time period when it was written. It was very warm -- a sort of sultry, sticky day, which makes you feel as if you had washed yourself in molasses and water, and had found that the chambermaid had forgotten to give you a towel. The very rust on the hinges of the Park gate has melted and run down into the sockets, making them creak with a sort of ferruginous lubricity, as you feebly push them open. The hands on the City Hall clock droop, and look as if they would knock off work if they only had sufficient energy to get up a strike. The omnibus horses creep languidly along, and yet can't stand still when they are pulled up to take in or let out passengers -- the flies are so persevering, so bitter, so hungry. Let us go over to Hoboken, and get a mouthful of fresh air, a drink of cool water from the Sybil's spring, a good roll on the green grass of the Elysian Fields. Down we drop, through the hot, dusty, perspiring, choking streets -- pass the rancid "family groceries," which infect all this part of the city, and are nuisances of the first water -- and, after stumbling our way through a basket store, "piled mountains high," we at length find ourselves fairly on board the ferry boat, and panting with the freshness of the sea breeze, which even here in the slip, steals deliciously up from the bay, which, even here in the slip, steals deliciously up from the bay, tripping with white over the night-capped and lace-filled waves. Ding-dong! Now we are off! Hurry out to this further end of the boat, where you see everybody is crowding and rushing. Why? Why? Why, because you will be in Hoboken fully three seconds sooner than those unfortunate devils at the other end. Isn't that an object? Certainly. Push, therefore, elbow, tramp, and scramble! If you have corns, so, most likely, has your neighbor. At any rate, you can but try. No matter if your hat gets smashed, or one of the tails is torn off your coat. You get ahead. That's the idea -- that's the only thing worth living for. What's the use of going to Hoboken, unless you can get there sooner than anyone else? Hoboken wouldn't be Hoboken, if somebody else should arrive before you. Now -- jump! -- climb over the chain, and jump ashore. You are not more than ten feet from the wharf. You may not be able to make it -- but then again, you may; and it is at least worth the trial. Should you succeed, you will gain almost another whole second! and, if you fail, why, it is only a ducking -- doubtless they will fish you out. Certainly they don't allow people to get drowned. The Common Council, base as it is, would never permit that! Well! here we are at last, safe on the sands of a foreign shore. New Jersey extends her dry and arid bosom to receive us. What a long, disagreeable walk from the ferry, before you get anywhere. What an ugly expense of gullies and mud, by lumber yards and vacant lots, before we begin to enjoy the beauties of this lovely and charming Hoboken! One would almost think that these disagreeable objects were placed there on purpose to enhance the beauties to which they lead. At last we are in the shady walk -- cool and sequestered, notwithstanding that it is full of people. The venerable trees -- the very same beneath whose branches passed Hamilton and Burr to their fatal rendezvous -- the same that have listened to the whispering love-tales of so many generations of the young Dutch burghers and their frauleins -- cast a deep and almost solemn shade along this walk. We have passed so quickly from the city and its hubbub, that the charm of this delicious contrast is absolutely magical. What a motley crowd! Old and young, men women and children, those ever-recurring elements of life and movement. Well-dressed and badly-dressed, and scarcely dressed at all -- Germans, French, Italians, Americans, with here and there a mincing Londoner, with his cockney gait and trim whiskers. This walk in Hoboken is one of the most absolutely democratic places in the world -- the boulevards of social equality, where every rank, state, condition, existing in our country -- except, of course, the tip-top exclusives -- meet mingle, push and elbow their way along with sparse courtesy or civility. Now, we are on the smooth graveled walk -- the beautiful magnificent water terrace, whose rival does not exist in all the world. Here, for a mile and a half, the walk lies directly upon the river, winding in and out with its yielding outline, and around the base of precipitous rocky cliffs, crowned with lofty trees. From the Bay, and afar off through the Narrows, the fresh sea breeze comes rushing up from the Atlantic, strengthened and made more joyous, more elastic by its race of three thousand miles -- as youth grows stronger by activity. Before us, fading into a greyish distance, lies the city, low and murky, like a huge monster -- its domes and spires seeming but the scales and protuberances upon his body. One fancies that he can still hear the faint murmur of his perpetual roar. No -- 'tis but the voice of the pleasant waves, dashing themselves to pieces in silver spray, against the rocky shore. The retreating tide calls in whispers, its army of waves to flow to their home in the sea. Take care -- don't tumble off these high and unbalustraded steps, -- or will you choose rather to go through the turn-stile at the foot of the bluff? It is very lean, madam -- which you are not -- and we doubt if you can manage your way through. We thought so! Allow me to help you over the steps. They are placed here, we verily believe, as a practical illustration of life -- up one side of the hill, and down the other -- for there is no material, physical, or topographical reason, that we can discover, for their existence. Here is a family group, seated on the little wooden bench, placed under this jutting rock. The mother's attention is painfully divided equally between the two large boys, the toddling little girl of six, who laughs and claps her hand with glee at discovering that she can't throw a pebble into the water, like her brothers -- and the baby, who spreads out his hands and legs to their utmost stretch, like the sails of a little boat which tries to catch as much of the breeze as it can, and who crows like a little chanticleer, in the very exuberance of his baby existence. Two half nibbled cakes, neglected in the happiness of breathing this pure, keen air -- which, by the way, will give them a tremendous appetite, by-and-by -- are lying among the pebbles, and ever the baby has forgotten to suck its fat little thumb.  Sybil’s Cave is the oldest manmade structure in Hoboken, created in 1832 by the Stevens Family as a folly on their property that contained a natural spring. By the mid-19th century the cave was a recreational destination within walking distance from downtown Hoboken. A restaurant offered outdoor refreshments beside the cave. https://www.hobokenmuseum.org/explore-hoboken/historic-highlights/sybils-cave/sybils-cave-today-and-yesterday/ The Sybil's Cave, with its cool fountain bubbling and sparkling forever in the subterranean darkness, now tempts us to another pause. The little refreshment shop under the trees looks like an ice-cream plaster stuck against the rocks. Nobody wants "refreshments," my dear girl, while the pure cool water of the Sybil's fountain can be had for nothing. What? Yes they do. The insane idea that to buy something away from home -- to eat or drink -- is at work even here. A little man, with thin bandy legs, whose bouncing wife and children are a practical illustration of the one-sided effects of matrimony, has bought "something to take" for the whole family. Pop goes the weasel! What is it? Sarsaparilla -- pooh! Now let us go on round this sharp curve, (what a splendid spot for a railroad accident!) and then along the widened terrace path, until it loses itself in a green and spacious lawn, lovingly rising to meet the stooping branches of the trees. This is the entrance to the far-famed Elysian Fields. Along the banks of the winding gravel paths, children are playing, with their floating locks streaming in the wind -- while prone on the green grass recline weary people, escaped from the week's ceaseless toil, and subsiding joyfully into an hour of rest -- to them the highest happiness. The centre of the lawn has been marked out into a magnificent ball ground, and two parties of rollicking, joyous young men are engaged in that excellent and health-imparting sport, base ball. They are without hats, coats or waistcoats, and their well-knit forms, and elastic movements, as they bound after the bounding ball, .... Yonder in the corner by that thick clump of trees, is the merry go-round, with its cargo of half-laughing, half-shrieking juvenile humanity, swinging up and down like a vessel riding at anchor. Happy, thoughtless voyagers! Although your baby bark moves up and down, and round and round, yet you fell the exhilarating motion, and you think you advance. After all, perhaps it would be a blessed thing if your bright and happy lives could stop here. Never again will you bee so happy as now; and often, in the hard and bitter journey of life, you will look back to these infantile hours, wondering if the evening of life shall be as peaceful as its morning. But the sun has swung down behind the Weehawken Heights, and the trees cast their long shadows over lawn and river, pointing with waving fingers our way home. The heart is calmer, the head clearer, the blood cooler, for this delicious respite. We thank thee, oh grand Hoboken, for thy shade, and fresh foliage, and tender grass, and the murmuring of the glad and breezy waters -- and especially for having furnished us with a subject for this chapter. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's Note: This article was originally written by Anthony P. Musso and published in the November 1, 2017 issue of the Poughkeepsie (NY) Journal. For information about current ice boating on the Hudson River go to White Wings and Black Ice here.  Built in 1863 by John Aspinwall Roosevelt to store his ice yacht boat, Icicle, the boathouse was subsequently used as a bait and tackle shop before falling into disrepair. It still stands on the former Rosedale estate in Hyde Park, once home to Isaac Roosevelt, grandfather of Franklin D. Roosevelt. ANTHONY P. MUSSO Poughkeepsie Journal (Poughkeepsie, New York) · Wed, Nov 1, 2017 HYDE PARK - On the east bank of the Hudson River along River Point Road in Hyde Park is a long, wood-frame structure that once served as a boathouse for John Aspinwall Roosevelt, uncle of former U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The parcel of land the building sits on was once part of an estate named Rosedale, which was owned by the late president's grandfather, Isaac. Beginning in the mid- to late-18th century, wealthy families from New York City started to acquire large tracts of land to establish estates, many in Hyde Park. Names such as Bard, Roosevelt, Rogers, Langdon, Astor, Vanderbilt and Mills were among the most prominent. A popular pastime for many of them became ice-yacht racing along the Hudson River. While it proved to be an exciting spectator sport for residents in the area, the activity was quickly dubbed a “rich man’s hobby.” Following the death of Isaac Roosevelt in 1863, his son John inherited Rosedale and had the boathouse erected to house his vessel, named Icicle. A champion ice yacht racer, Roosevelt's boat — at 68 feet, 10 inches long and boasting a sail spread of 1,070 square feet — was the largest ice boat in the world at the time. “Icicle is now owned by the New York State Museum {Editor Note: "Icicle is on loan from the National Park Service Home of Franklin Delano Roosevelt] and is currently on loan to the [Hudson River] Maritime Museum in Kingston,” said Jeffrey Urbin, education specialist at the FDR Presidential Library and Museum. The boathouse featured six casement windows, a paneled wooden door and a board and batten-hinged door. The lower portion of its northern end was constructed of stone. The design of the boathouse was crafted specifically to store Roosevelt's ice yacht fleet while the space available above was occupied by sails. The building’s double-pitched roof provided additional space in the loft, in his younger years, FDR stored his 28-foot ice yacht, named Hawk, in the structure; the boat was a Christmas gift from his mother, Sara, in 1901. In 1861, at 21 years old, John Roosevelt founded and became the commodore of the Poughkeepsie Ice Yacht Club and, in 1885, he founded and held the same position with the Hudson River Ice Yacht Club. Both organizations still exist today. The area the boathouse occupies became known as Roosevelt Point and, during the latter part of the 19th and early 20th centuries, was used as the starting point for many world-class races held along the river. With a smaller version of the original Icicle — this one spanning 50 feet with a 750-square-foot sail area — John Roosevelt won the Ice Yacht Challenge Pennant of America in 1888, '89, ‘92 and ‘99. An additional structure that no longer exists at the site but once sat just south of the boathouse was known as the Roosevelt Point Cottage. Built in the 1850s as a tenant dwelling on the estate, records indicate that, from 1877 through 1886, it was occupied by Rosedale's gardener, Robert Gibson, The cottage maintained a front room that featured a stove, in which ice yacht enthusiasts could find warmth while waiting for a favorable wind to take their vessels on the river. “Ice yachting went into decline after 1912 as other pursuits, such as the automobile and airplane, captured the fascination of the public,” said John Sperr, of the Hudson River Ice Yacht Club. “World events were also a factor in the demise of ice yachting on the Hudson, as the onset of World War II found it necessary to keep the river open in winter so the large munitions and war material produced in Troy, Watervliet and Schenectady could be readily put into service.” The land the boathouse occupies was separated from Rosedale during the 1950s, when single-family homes were built on the former estate. Today, along with Isaac Roosevelt's house (located closer to Route 9), the boathouse remains vacant but an original remnant of the thriving 19th-century estate. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

|

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 [email protected] Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |