History Blog

|

|

|

|

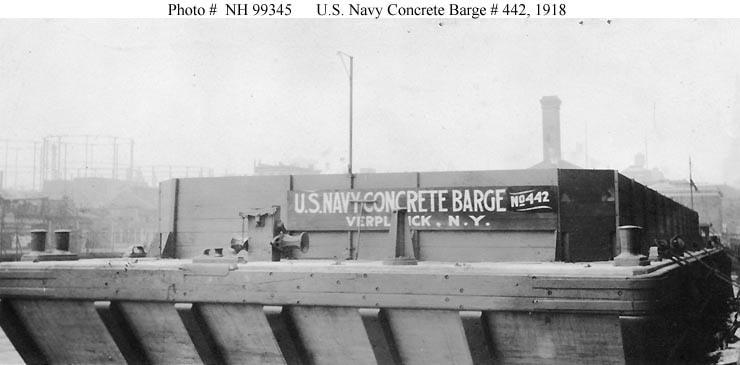

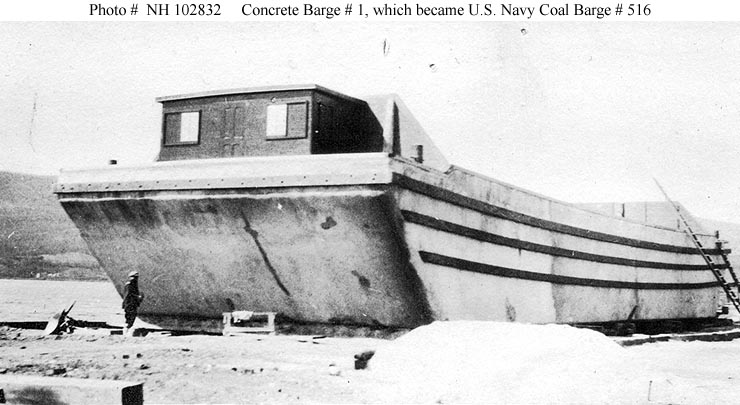

itle: Concrete Barge # 442 Description: (U.S. Navy Barge, 1918) In port, probably at the time she was inspected by the Third Naval District on 4 December 1918. Built by Louis L. Brown at Verplank, New York, this barge was built for the Navy and became Coal Barge # 442, later being renamed YC-442. She was stricken from the Navy Register on 11 September 1923, after having been lost by sinking. U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph. Hiding away in Rondout Creek, New York at 41.91245, -73.98639 is the last known surviving example of a World War I Navy ‘Oil & Coal’ Barge. It is less than a kilometer up the Rondout Creek from the Hudson River Maritime Museum. Based on a lot of ‘Googling’, it seems probable this is the first time that the provenance and history of this particular relic of concrete shipbuilding in the United States during the World War I era has been recognized. [Editor's Note: The concrete barge is featured on the Solaris tours of Rondout Creek.] The hulk is, in fact, the initial prototype of a ‘Navy Department Coal Barge’, concrete barges that were commissioned by the Navy Department : Bureau of Construction and Repair. This was the department of the U.S. Navy that was responsible for supervising the design, construction, conversion, procurement, maintenance, and repair of ships and other craft for the Navy. Launched on 1st June 1918, the ‘Directory of Vessels chartered by Naval Districts’ lists ‘Concrete Barge No.1’, Registration number 2531, as being chartered by the Navy from Louis L. Brown at $360 per month from 11th September 1918. In Spring 1918, the Navy Department had commissioned twelve, 500 Gross Registered Tonnage barges from three separate constructors in Spring 1918 to be used in New York harbour.  Navy Barge #516 which was the first prototype. It is believed that the barge at Rondout Creek is this particular barge based on the subtly different lines of her bow. Possibly photographed when inspected by the Third Naval District on 5 April 1918. She was assigned registry ID # 2531. This barge, chartered by the Navy in September 1918, was returned to her owner on 28 October 1919. While in Navy service she was known as Coal Barge # 516. U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph. AuthorsRichard Lewis and Erlend Bonderud have been researching concrete ships worldwide for many years. They have identified over 1800 concrete ships, spanning the globe, of which many survive. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

0 Comments

The Hudson River was used as a road for hundreds of years for transport of people and goods before there were paved roads or railroads. The major form of transport on the river from the early 1600s to the early 19th century was the Hudson River sloop, an adaptation of a Dutch single-masted boat which was brought here by the Dutch settlers who were the dominant group among the early European settlers in the Hudson Valley. Everything and everybody traveled by Hudson River sloop, but they didn’t travel fast. In those pre-engine days, it could take a week to sail between New York and Albany. According to ads of the times, the sloops operated on a two-week schedule (one week down and one week back), to allow for the vagaries of the wind and the time it took to fill the boat at various landings and towns. For passengers in a hurry, or perishable freight, such a schedule could be a problem. After 1807, with the advent of the steamboat, life for passengers on the Hudson in a hurry became much better. From a one week trip between New York and Albany, the time was reduced to slightly more than one day, and then became even faster as better and better steamboats and engines were built. However, freight continued to travel by slower sailing vessels because it was much cheaper to ship cargo that way. As more and more steamboats came onto the river and competition made shipping on these boats cheaper, perishable freight like fruit, vegetables and milk traveled by steamboat. Less perishable bulk cargoes traveled in barges pulled by steamboats especially built for towing. Even so, sailing vessels, sloops and schooners still carried bulky heavy cargoes like bluestone and cement until the end of the 19th century. The schooners included a steady traffic of coastal schooners from New England which would bring lumber to the Hudson Valley and return home with cargoes like coal, bricks, bluestone and cement. Ironically, though, the coastal schooners usually did not sail up the Hudson but were towed in convoys by steam towboats or tugs. The smaller Hudson River sloops and schooners, whose scale was more in keeping with the narrow reaches of the Hudson, could sail up the river. By the mid-19th century the railroad began to come on the scene in the Hudson Valley to compete with boats. The railroad had the advantage of being able to run in the winter when the river was frozen and closed for boat traffic, so it steadily gained favor with shippers. However, the river retained a large amount of freight traffic because it was still a cheap way to ship things. Towing was a big business on the Hudson River during most of the 19th century into the early 20th century. The towing steamers were first outmoded passenger steamers with cabins and extra decks removed. Then steamers especially made for towing were built, like the famous Norwich, the Oswego, the Austin and others which still resembled stripped down passenger steamboats with the usual side paddlewheels. However, around the time of the Civil War a new type of towboat with a screw propeller appeared on the scene. This was the tugboat which we are still familiar with today, a small but powerful vessel, whose attractive shape is easily recognizable and used in many work situations worldwide. Towboats and tugs pulled long strings of barges, often as many as forty, carrying many types of cargoes slowly up and down the Hudson day and night from the late 19th into the early 20th centuries. Usually a second helper tug was employed to take barges on and off the tow as it moved along, helping with the towing also as needed. Often the individual barges had captains who lived in tiny houses onboard their boats, sometimes with their families accompanying them. It was not unusual to see laundry hung out on the backs of the barges or dogs and children playing on deck. Small children were usually tethered with some sort of rope to keep them from falling overboard. Small supply boats called bumboats came alongside the tows as they moved slowly along to sell groceries and other necessities to the barge families. Rondout was the home of the Cornell Steamboat Company, which was the dominant towing company on the Hudson from the 1880s through the 1930s, with a fleet of up to 60 tugs and towboats of all sizes. Rondout was also the home of a number of boat builders who built hundreds of barges and canal boats over the years to carry many different types of cargoes on the Hudson and on the canals like the Delaware and Hudson which fed into the Hudson. Most of the towns along the Hudson had boat-building operations in the early days of the sloops, but by the late 19th century boatbuilding was concentrated in fewer places, like Newburgh and Rondout. What were the cargoes carried on the Hudson River by boat? Farm products and wood dominated the trade from the 17th into the 19th centuries. Industrial products, particularly building products like cement, bluestone and bricks produced in the Hudson Valley in the 19th and early 20th centuries, were the major cargoes traveling on the river to New York City to build the city. Coal was also a major cargo, coming to the Hudson on the Delaware and Hudson Canal in the 19th century, and later by rail from eastern Pennsylvania. Ice cut in the Hudson and lakes along the river was also another major cargo from the mid-19th century into the 1920s transported in fleets of covered barges. Grain from the west was carried on the Hudson, and fruit produced in the mid and upper Hudson regions was transported in huge quantities by steamer through the 1930s. In the 20th century, self-propelled freighters served to carry cargoes not handled by towboats and barges. Sometimes these were cargoes that traveled to or from distant ports, sometimes across the ocean or halfway around the world. Some cargoes that had previously come by coastal schooner, like lumber, now arrived by freighter. Liquid cargoes arrived by tanker including oil and molasses. Fuel oil is today the dominant cargo on the Hudson and it travels by barge and by tanker. The molasses which used to go to Albany by tanker was used as a component in cattle feed. Gypsum remains a cargo carried by freighter on the Hudson. Of the old cargoes carried on the Hudson, few remain today. Only cement and crushed rock or traprock remain of the old building materials excavated and produced along the banks of the Hudson and carried by barge. Most cargo moving along the Hudson today goes by rail or road. Where water was once the cheapest way to ship along the Hudson, it is no longer necessarily true. The industries that shipped by water are gone for the most part. Also much of the bulk cargo that once traveled to Albany from all over the world like bananas or foreign cars now go elsewhere. Those colorful days are gone and are missed by those who remember them. AuthorThis article was written by Allynne Lange and originally published in the 1999 Pilot Log. Thank you to Hudson River Maritime Museum volunteer Adam Kaplan for transcribing the article. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor’s Note: The following text is a verbatim transcription of an article featuring stories by Captain William O. Benson (1911-1986). Beginning in 1971, Benson, a retired tugboat captain, reminisced about his 40 years on the Hudson River in a regular column for the Kingston (NY) Freeman’s Sunday Tempo magazine. Captain Benson's articles were compiled and transcribed by HRMM volunteer Carl Mayer.. This article was originally published November 28, 1976. One night back in the late 1930’s, I was pilot on the tugboat “Cornell No. 41” of the Cornell Steamboat Company. We were the helper tug on a tow in charge of the tug “Lion” headed for Albany. As was the custom in those days, the helper tug would take off and add barges for local delivery as the tow slowly moved up or down the river. When we were off Athens about 2 a.m., we went along the tow to take off two cement lighters to land them at Hudson. The cement lighters were alongside a big coastwise barge in the tow destined for Albany. My deckhand, the late William “Darby” Corbett of Port Ewen, had to climb up on the coastwise barge to cast off the lines of the cement lighters. As “Darby” was about to let the lines go, I saw this big dog come sneaking up the deck in the shadow of one of her hatches. He looked as if he was about to pounce, I yelled over, “Watch out ‘Darb’, here comes a dog after you!” With that, “Darby” turned quickly, caught the dog with his foot and raised him over the barge’s low rail almost quicker than the eye could see. Overboard the dog went, between the barges, without a sound. I thought sure the dog was a goner. We saw nothing of him as we pulled away from the tow with the cement lighters. The next morning as we lay on the other side of the tow, the captain of the coastwise barge came over and asked if we had seen anything of his dog. We didn’t have the heart to tell him what happened. Later that morning, when we were up off New Baltimore, there, to my incredible surprise, was the dog running along the shore, following the tow. When we landed the coastwise barge in the old D&H slip just below Albany, he was waiting for us. He sure was a tuckered out dog. Fortunately, we were bucking an ebb tide during the last part of the tow, which slowed our rate of progress overground. The dog must have swum to shore at Athens and followed the lights of the tow until daylight. How he ever lived after going down between the barges, no one but the dog ever knew. AuthorCaptain William Odell Benson was a life-long resident of Sleightsburgh, N.Y., where he was born on March 17, 1911, the son of the late Albert and Ida Olson Benson. He served as captain of Callanan Company tugs including Peter Callanan, and Callanan No. 1 and was an early member of the Hudson River Maritime Museum. He retained, and shared, lifelong memories of incidents and anecdotes along the Hudson River. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Happy Labor Day! For today's Media Monday, we thought we'd highlight this recent lecture by Bill Merchant, historian and curator for the D&H Canal Historical Society in High Falls, NY. "Child Labor on the D&H Canal" highlights the role of children on one of the biggest economic drivers of the Hudson Valley in the 19th century. Child labor was a huge issue in 19th and early 20th century America (learn more) throughout nearly every industry, including the maritime and canal industries. Although many canal barges were operated by families, many were also operated by single men who exploited orphans and poor children, often with fatal results. Children were most generally used as "drivers," also known as hoggees, who walked with or rode the mule or horse who pulled the barge through the canal. Work was long, often sunup to sundown or even longer, as the faster barges could get through the canal, the faster they could return and pick up a new cargo, thus making more money. The Kingston Daily Freeman reported a Coroner's Inquests on July 18, 1846, which recorded several deaths related to Rondout Creek and the D&H Canal, including a young boy. It is transcribed in full below: Coroner's Inquests. On the 11th, Coroner Suydam [sp?] held an inquest at Rondout on the body of Joseph Marival, a colored hand on board the sloop Hudson of Norwich, Ct. He went in the creek to bathe, and was accidentally drowned. The same officer held an inquest at [?] Creek Locks on the body of Henry Eighmey, on the 15ht, drowned in the canal by a fall from a boat about noon. We have record of a third by Mr. Suydam, held at Rosendale on the 12th, on the body of Andrew J. Garney, a lad of ten years old, a rider, who it was supposed fell from his horse into the canal about day break of that morning, a verdict conformable being rendered. In connection with the last case, we would remark, that the crew consisted of one man with the driver who was drowned. That the boat had been running all night [emphasis original]; that about three o'clock in the morning the man spoke to the land and was answered, and that some time afterwards he missed him, and concluded he must have fallen into the canal. Is there any thing strange in the fact that a lad of ten years, worn down with the fatigues of a long day and a whole night in the bargain, should drop into another world? Now we do not mean to mark this as a singular case, by any means. It is but one of the like occurring almost daily on the canal. Lads are hired at a mere pittance, and men are determined to get as much work out of them as possible, without the least regard to health, comfort, or safety. The poor children are toiling from daylight to dark, and if in addition they are forced to nod all or part of the night, the consequent sleep and death is nothing to be wondered at. We would call attention to this subject on the part of those who may able to devise a mode of reaching such cases. Nor would it be out of place in the Coroner's jury in the next instance should state the whole [emphasis original] truth in the verdict. Most laborers on the canal were paid at the end of the season, but it was not uncommon for unscrupulous barge operators to cheat the boys of their wages and abandon them in random canal towns. Even when working with their families, children who lived aboard barges sometimes had hard lives. Although the Delaware & Hudson Canal closed in 1898, children and families continued to work on the newly revamped New York State Barge Canal system and canals in Ohio and elsewhere into the mid-20th century. In 1923, Monthly Labor Review published an article entitled "Canal-boat Children," which looked at the labor, education, and living conditions of children on canal boats. Of particular interest was safety, as the threat of drowning or being crushed in locks was near-constant. Still, many families were able to make decent livings aboard canal barges, until tugboats took over canal barge towing in the mid-20th century. To learn more about New York Canals, visit the Hudson River Maritime Museum's exhibit "The Hudson and Its Canals: Building the Empire State," or visit the newly revamped D&H Canal Museum in nearby High Falls, NY. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Today's Featured Artifact is one of the larger pieces in our collection! This steam engine is from the Merritt-Chapman & Scott crane barge Monarch. One of four that powered the hoisting apparatus, the Monarch was built in 1894 and could lift 250 tons. This particular engine is one of a pair that worked to swing the crane boom from side to side. The two other engines did most of the heavy lifting, raising the boom and the hook. This engine is a compound steam engine and is in working order. The engine is on loan from Gerald Weinstein. Merritt-Chapman & Scott was a noted marine salvage corporation with history that dated back to the 1860s and the Monarch was just one of their many vessels. Technically an A-frame floating derrick, the Monarch was used to lift heavy items such as railroad cars and engines, turbines, and other heavy cargoes onto and off of ships and docks, as well as raise sunken vessels such as barges, tugboats, and even large steamboats. In the above photo, you can clearly see how the Monarch's A-frame steam derrick crane worked. Here, the hoisting engine on display at the museum is working in tandem with its partner to move the crane arm to the side in order to create safe conditions to raise (or lower) the equipment off or on the deck of the Champion. By tilting far to the right or starboard side of the barge, the crane arm is able to lift and lower straight up and down, dramatically reducing the danger that the cargo will swing and wreck either of the barges or their hoisting apparatuses. In this photo you can see how far over the Monarch would tilt when hoisting something heavy! The barge would often heel over like that, sometimes submerging the edge of her decks in the water. Merritt-Chapman & Scott went on to be involved in a number of large marine construction projects over the years, including the construction of the Kingston-Rhinecliff Bridge in 1957 and the Throgs Neck Bridge in 1961. It is unclear if the Monarch was used on either project. The Monarch retired in the 1980s after 90 years of service. She outlasted Merritt-Chapman & Scott itself, as the company was dissolved in the 1970s. You can find out more about Merritt-Chapman & Scott and see more images of the Monarch by visiting the Mystic Seaport Archives, where the corporate records are held. And if you'd like to see a piece of the Monarch in person, be sure to visit the Hudson River Maritime Museum and swing by the big green machine, tucked in the corner of the East Gallery. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

This week's featured artifact is a recent acquisition! This large model of the Erie Railroad Barge No. 271 was donated by model maker John Marinovich, Jr. His grandparents and mother lived and worked aboard this barge for about five years after emigrating to the United States from Austria in 1912. The model has a number of very detailed aspects, including these living quarters at the stern of the barge. Mr. Marinovich even modeled his grandmother and mother along with window boxes, which he said were part of the original barge while the family lived aboard. The model has a removable roof, some removable walls, and yes, it floats! The Hudson River Maritime Museum was lucky to be able to receive so many historical details and photos in addition to the model itself. Mr. Marinovich graciously shared this newspaper article about his mother entitled, "Home on the Hudson," written by Ruth Woodward for Beachcomber, August 10, 1978. We reproduce the article below, interspersed with photographs provided by Mr. Marinovich: Beachcomber, August 10, 1978 HOME ON THE HUDSON By Ruth Woodward Marinovich means "son of a sailor" in the Croatian language. Mary Marinovich of Harvey Cedars acquired the name by marriage but she is a true daughter of a sailor. She spent her earliest years living on a Hudson River barge, with the deck as a play area and the whole panorama of the Hudson waterfront to stimulate her interest in faraway places. In the days before container ships, the Hudson River was dotted with barges, and Erie Barge 271 was the "old homestead" for Mary. A barge on the Hudson was a busy and exciting place for a small child to live. Ships from all over the world docked at piers along the New York Harbor. Barges were dispatched to meet the ships and transport their cargoes to factories, refineries or railroad cars. Large sliding doors on the roof of a barge's freight house would be opened and part of the ship's cargo would be lowered into the barge. The longshoremen on the dock would board the barge to arrange the cargo which was usually bundled in large burlap bags. The bags would be stacked until the freight house was filled. With the barge loaded the captain signed for his cargo and learned its destination from the dock master. As soon as one barge was loaded it would be pushed to another part of the dock and the next barge moved into place to be loaded. Tugboats would then pull the barges to the piers where the cargoes were to be unloaded -- to Hoboken, Brooklyn, West New York. As soon as a barge captain reported that his cargo had arrived a ramp would be raised from barge to dock, the longshoremen would come with their hand trucks and load up. For the young children on the barge it was fun to watch the men run up and down the ramp and dump their cargo on the dock. When the barge was unloaded the captain reported to the office on the dock, where there would be orders waiting, telling him where to pick up the next load. Mary Marinovich's story has its beginning on the island of Losinj in the Adriatic Sea. This was in the province of Istria, part of pre-World War I Austria. The land on Losinj was too poor to make much of a living from farming, so it was an island of sailors. Like so many European men around the turn of the century, young Joseph Sokolich left his wife and small son in the old- country and came to America alone to try to make a better living for this family. He was a seaman and he wanted to be near water so he found a job on the Hudson, on an Erie Railroad barge. When he was ready to send for his wife and son, he applied for a barge with living quarters for a family. Men with families were given priority when applying for boats with two or three rooms for living quarters. Living on a barge was a good way for a young family to get a start in the new country. Most families who rented apartments found it necessary to rent rooms to make ends meet, but the barge captain and his family had privacy and independence, as well as free rent. Coal for the stove and kerosene for lamps was provided by the Erie Railroad. Cargoes were usually things like rice, coffee, flour, sugar, spices, coconut - bags broke and the barge family was welcome to whatever spilled out. And you could barter with other captains when you docked for the evening. Those with refrigerated storage always had fruit to trade. The Hudson was so clean in those days that you could take a rowboat and go under a dock to crab or fish. And if you happened to have a long haul down the center of the river, you could throw a line in and sit and fish while the tug was pulling you to the dock to unload. You might run out of fresh milk and eggs because there wasn't always an opportunity to leave your boat to get to a store. But there was always plenty of food and the family was sheltered and warm and cozy in the barge. Mary was born in Hoboken because her mother new of a good midwife there. Mother and baby returned to the barge when Mary was ten days old. Later, when sister Tina was born. the midwife came on board the bare to deliver the baby. Whenever word got out that a pregnant woman was aboard a barge, the tugs would signal the news to each other with a signal to "Be Careful! Don't hit this barge hard." When a woman's time for delivery drew near, the dispatcher would see that the barge was sent to drydock for repairs or had some other excuse for staying docked in one place until the baby was safely delivered. To all of the immigrants it was a great source of pride to have a child born in America. The Sokolich barge had a cabin with two large rooms, a kitchen and a bedroom. The bedroom had built-in bunks and the kitchen, dominated by the big, black stove, had built -in cupboards. The deck in front of the cabin could be used as porch or yard or outdoor sitting room and when the freight house was unloaded and empty, it was a room of many purposes. There was room here for Mary's other to set up the washtub and do the family wash. Water had to be brought on board only when the barge was docked in designated areas. The captain would be given a little extra time in order to take on water and this was usually a good time to get at the washing. The freight house was also a large playroom for the children. When it was empty, Captain Sokolich would put up gates so that the children could play there in safety. But Mary remembers sometimes playing in the freight house when it was loaded. "We'd jump all over the bags and play hide and seek. We didn't have any trees to bide behind, so we hid behind the bags instead." And the freight house was the "company room." As soon as the barge docked for the night families looked around to see whether any friends were at the same dock. Each barge captain had a distinctive ornament or figurehead on his boat so that it could be easily recognized. There were German, Dutch, Belgian and Austrian families plying the river, all people who had made their living on the water in Europe. Friends would gather in one of the empty freight houses for the evening. There was always wood floating on the river so the men made benches and tables for the freight houses in their spare time. The tables and benches were brought out when company came and the men settled down to an evening of cards and the women to sew and chat. With the abundance of flour and sugar available on the barges there were always homemade cakes and breads and rolls to pass around. Mary remembers that one of the nicest things that could happen was to learn that a ship was expected to be two or three days late arriving in the harbor. Then the barge could stay in one place for a few days and there would be time for her mother to go shopping to buy shoes for the children and fabric to make them clothing. If they were in an area where they had friends living ashore they could fit in a rare visit. The children first learned to read from the signs along the river. They spelled out "Lipton Tea, Coffee, Cocoa" as the sign flashed on and off as they approached Hoboken. Their geography lessons came when they passed ships of all nationalities docked in New York harbor. Mary remembers seeing Japanese ships with the crew sitting on the deck eating from a large communal pot. Her mother would tell the children where the ship was from and what the men were eating. Most exciting would be to pass a German passenger ship with a brass band in the bow. The children could prance to the sound of the oom-pah-pah as long as they could hear the music. When Mary's brother Joe reached school age, he first stayed in Hoboken at a boarding school run by the church, joining the barge only on weekends. But he was homesick for this family and as soon as he was able to travel by himself, he came back to the barge after school each day. Every afternoon Father would telephone from the dock, leaving a message at the school telling this son just where the barge would be docked for the night. And young Joe would travel by trolley to wherever his home happened to be. This was customary for the barge children. Even the tiny ones learned the trolley routes and traveled across the city to get home each night. Even with the camaraderie of the other barge families on the river, it was a lonely life for the women. It was difficult for them to shop and it was difficult for them to get to church. The barge was the responsibility of the captain so some member of the family usually had to stay on board, though occasionally another bargeman could be asked to keep an eye on the boat for a short time. When barge people left their boats, they talked of "going up the street." But it was difficult for the women to get up the street because it meant walking through the dock areas and the railroad yards and it was not always safe. The captain had to be ready to move whenever orders came, but if a captain knew that there would be an hour's time before a tug's arrival, he would "go up the street" and bring back a bucket of milk. Mary still remembers what a treat this was as a change from condensed, canned milk. To while away the time on the barge, Mrs. Sokolich learned to play dominoes and taught the children to ply. She carved picture frames from cigar boxes and she delighted in making paper flowers. "My mother's barge was the talk of the river because she loved flowers so much. Right in front of the cabin she had a big pot of ivy and she had window boxes for flowers. And when she couldn't grow plants, she made them. She would take a piece of straw from the broom and cover it with green crepe paper for the stem. Then she would cut and fold paper to make petals and turn them on a matchstick to create her own 'roses.' She worked had to make our cabin homelike. She scrubbed the wood floor until it was white and her stove was always polished like a mirror." Life for the barge families changed abruptly when the United States entered World War I. Instead of flour and sugar and spices the barges hauled barbed wire, machinery and ammunition. It was no longer safe for families to live on the boats and they move ashore to a house in West New York, New Jersey. All of New York harbor was declared a war zone, since it was used for troop embarkation and debarkation. Captain Sokolich and the other barge men had to show their credentials whenever they came on the piers and they had to leave the area as soon as they were off duty. Many people were suspicious of the German and Austrian men, even though they had become American citizens. The Sokolich family never returned to the barge to live. "Once we were able to go to the store and buy a loaf of bread, we never wanted to go back," Mary says. "I can still remember how exciting it was when we moved to shore and turned on the faucet and got all the water we wanted. My mother never could get used to letting the water run!" When the war ended, Mary's father found a job on a Lackawanna Railroad lighter. A lighter was an open boat with a small cabin in front. The freight area was open and the lighter carried heavy articles like tires, cars and steel pipes that could be exposed to the weather. John Marinovich laughingly reminded his wife that when Captain Sokolich no longer had his family on board that he had "another woman" on his boat. The Captain had a life-sized cardboard figure of a Moxie girl, advertising a popular soft drink. The Moxie girl was a pretty and had a winning smile and he took the head from the figure and attached it to the cabin window with springs. As the lighter plied the river, the men working on the docks would wave and grin and flirt with the girl who was smiling and nodding to them from the cabin window. Sailors on the Rhine had the Lorelei to tempt them, but the men on the Hudson had a Moxie girl! The model of the Erie RR Barge No. 271 is now safely ensconced behind a plexiglas bonnet in the Charles Niles Model Shop exhibit in the Hudson River Maritime Museum. You can see it in person whenever you visit! If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Today's Media Monday features this 10-minute tour of lower Manhattan from 1937!

Produced by the Van Beuren Corporation as a travelogue, part of the "World on Parade" series, "Manhattan Waterfront" was distributed by RKO Pictures in 1937. Watch the full movie below!

We see tugboats and sailing schooners, barge families, Fulton Fish Market, We also see the lives of the super-rich contrasted with the lives of the poor, living in waterfront shacks, or in neat houses built on top of abandoned barges. Interestingly, despite the fact that 1937 was the height of the Great Depression, the narrator blames the indigent for not taking advantage of the "land of opportunity." We also see most of Manhattan's bridges, including the 6 year old George Washington Bridge with only one deck.

How much of lower Manhattan can you still recognize today?

If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's Note: This story is from the October 5, 1889 issue of Harper's Weekly. The tone of the article reflects the time period in which it was written. "A Barge Party - On our next page we have a view of a merry party enjoying a moonlight row on the Hudson River. The barge belongs to the Nyack Rowing Association. The scene is that wide and beautiful expanse of the Hudson which our Dutch ancestors named the Tappan Zee. It lies between Tarrytown and Nyack, and although not beyond the reach of tide-water and subject to the current, it still possesses the attraction of a calm and beautiful lake. Viewed from certain points it loses the impression of a river altogether, and seems a fair and beautiful sheet of water locked in by towering hills. The light-house in the centre of the picture is known as the Tarrytown Bay Light. On the left lies Kingsland Island, and in the background we have the village of Tarrytown, adorned with its gleaming electric lights. These rowing parties are a source of keen delight to the lady friends of the members of each association. So far the clubs had not yielded sufficiently to the spirit of the age to admit lady members, and if any one connected with the association desires to give his fair friends an outing, he must engage the barge beforehand and make it a special event. As a general thing it is required that some member of the club shall act as coxswain; this to assure safety to the previous craft. The party may then be made up in accordance with the fancy of the gentleman who acts as host. Most of the associations have very attractive club-houses, where, after the pleasure of rowing has begun to pall, parties can assemble, have supper, and if there are lady guests sufficient, enjoy a dance. The club-house of the Nyack Association is a very attractive structure, built over the water, and forms a pleasant feature in the landscape. The members of these clubs are not heavily taxed, their dues scarcely amounting to more than $25 or $50 per year, yet their club-houses are daintily furnished, their boats of the best and finest build, and all their appurtenances of a superior order. So much can be done by combination. In our glorious Hudson River we have a stream that the world cannot rival, so wonderful is its picturesque loveliness. High upon the walls of the Governor’s Room in the New York City Hall is a dingy painting of a broad-headed, short-haired, sparsely bearded man, with an enormous ruff about his neck, and wearing otherwise the costume of the days of King James the First of England. Who painted it nobody knows, but all are well aware that it is the portrait of one Hendrik Hudson, who “on a May-day morning knelt in the church of St. Ethelburga, Amsterdam, and partook of the sacrament, and soon after left the Thames for circumpolar waters.” It was on the 11th of September, 1609, that this same mariner passed through a narrow strait on an almost unknown continent, and entered upon a broad stream where “the indescribable beauty of the virgin land through which he was passing filled his heart and mind with exquisite pleasure.” The annually increasing army of tourists and pleasure seekers, which begin their campaign every spring and continue their march until late in the autumn, sending every year a stronger corps of observation into these enchanted lands, all agree with Hendrik Hudson. Certainly it only remains for tradition to weave its romances, and for a few of our more gifted poets and story-tellers to guild with their imagination these wonderful hills and valleys, these sunny slopes and fairy coves and inlets, to make for us an enchanted land that shall rival the heights where the spectre of the Brocken dwells, or any other elf-inhabited spot in Europe. AuthorThank you to HRMM volunteer George Thompson, retired New York University reference librarian, for sharing these glimpses into early life in the Hudson Valley. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

In 1825, the Erie Canal was completed with the hopes of improving and expanding economic opportunity between the areas surrounding Lake Erie and the Hudson River. Having proved to be a great success, the state of New York seized many opportunities to further develop the waterway. As such, they undertook multiple enlargement projects. The final project integrated the Erie Canal into the New York State Barge Canal system. Finished in 1918, the system also includes the Cayuga-Seneca, Champlain, and Oswego canals. All of which were originally built within a few years of the Erie Canal’s completion. The project not only enlarged the dimensions of all four canals but also altered their original routes. The Barge Canal era is represented in a shipwreck located in Kingston’s Rondout Creek, the Frank A. Lowery. Constructed in Brooklyn, New York the same year that the Barge Canal was completed, the Lowery was likely built to take advantage of the opportunities provided by the new-and-improved waterway. The barge Frank A. Lowery, then registered as OCCO 101, began operation under the ownership of the Ore Carrying Corporation. According to the 1921 publication of the Annual Report of the Superintendent of Public Works for New York State, “the Ore Carrying Corporation … engaged in the transportation of iron ore from Port Henry on Lake Champlain, to Elizabethport, N.J.”. The report also notes that in terms of the amount of ore shipped per season, the company was substantially more productive in 1920 than it was in 1919. In fact, the company shipped over three times the amount of ore in 1920 than it did the previous season. Having joined the company’s fleet in 1918, the OCCO 101 likely assisted the company in achieving this feat. Ownership was transferred to the L. & L. Canal Line in 1926 and the vessel was renamed L & L. 101. As shown in the 1930 publication of Inland-waterway Freight Transportation Lines in the United States, the L. & L. Canal Line shipped steel and pig iron on the New York State Barge Canal. Based in New York City, the line had six wooden barges that could be found traveling the waters to and from Buffalo, New York. Finally, Frank A. Lowery purchased the vessel and renamed it after himself in 1929. Though much about Lowery remains unknown, the Merchant Vessels of the United States publications for the years 1930 and 1936 list Lowery as living in Creek Rocks, New York. However, in the publication for the year 1951, he is listed as living in Athens, New York. The later record also notes that he owned six vessels, including the Frank A. Lowery. While it is unclear who initiated the renovations, the vessel was refit with an engine in 1929. This renovation distinguished the Lowery from other canal boats and allowed for its classification as a Hoodledasher, or a powered canal boat. As such, it could move itself through the water with two hundred and forty horsepower and could be used to both tow and carry cargo. Following these renovations, the Lowery measured 104 feet in length, 21 feet in beam, and had a tonnage of 195 net tons. Surely, such a vessel was viewed to be a more efficient option. The Frank A. Lowery was put to use as the leading vessel of the Lowery flotilla, which also included the six barges it towed. A 1955 New York District Court case, further discussed below, provides a glimpse into the history of the vessel under the ownership of Frank Lowery. This includes what was transported in the vessel’s cargo hold as well as the routes it covered: “The Lowery flotilla . . . sailed the waters of the Hudson River and Barge Canal for a considerable number of years. It was old in the service of carrying cargo, well known to the trade and canal and river people, and on many… occasions it carried scrap iron west from New York City to Buffalo, and grain east from the terminal at Buffalo to the City of Albany.” In 1953, the Frank A. Lowery was involved in an incident that resulted in a district court case. According to the case report, the Lowery flotilla was on its way to the Port of Albany when a steel barge collided with the last vessel in the flotilla tow, the Marion O’Neill. The steel barge was being pushed by the Ellen S. Bouchard of the Bouchard Transportation Company. Having caused a chain reaction, the Marion O’Neill then collided with yet another barge in the tow, the Mae Lowery, and both vessels subsequently sank. The Mae Lowery’s misfortune continued when it was struck by the unsuspecting Clayton P. Kehoe of the Kehoe Brothers Transportation Company nearly two hours after the initial collision. The day’s events resulted in one presumably fatal casualty, the captain of the Marion O’Neill. The Lowery was abandoned east of Rondout Creek’s Sunflower Dock following an accident in 1953, perhaps the one mentioned here, and her valuable effects were salvaged five years later. The vessel’s tell-tale hanging and lodging knees, half-round bow, and parallel sides allowed for the easy identification of the wreck for many years. However, the structure continues to deteriorate with the erosive nature of weather and ice. Soon, only her keel will remain. AuthorLauryn Czyzewski is a Hudson River Maritime Museum volunteer. Her interests include twentieth and twenty-first century maritime history and shipwrecks. She graduated from SUNY Potsdam with a bachelor’s degree in Archaeological Studies. Lauryn would like to thank the editors of this article, Sarah Wassberg Johnson and Mark Peckham. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Like many nautical terms, the words “barge” and “scow” are fraught with diverse definitions depending upon timeframes, local usages and individual perspectives and backgrounds. In this way, these words are not unlike “ship,” which in common usage refers to anything big capable of independently making its way across the water. At various times in history, the word ship referred only to sailing vessels with square sails on three masts (as opposed to brigs, barks, barkentines, etc.) while also meaning the collective team of crew and officers of any vessel. Paradoxically, the big steamers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries on the Hudson were never called ships; they were always referred to as boats regardless of size or capability. Historically, the words barge and scow have applied to everything from the flat bottomed sailing barges of the Thames, floating pleasure palaces and funerary boats to the garbage boats of the first half of the twentieth century. Today, these terms generally bring to mind simple floating boxes that carry cargo and are pushed or towed by tugboats. They often suggest craft with flat bottoms and shallow drafts. Let’s take a brief look at what these words have represented here on the Hudson River. Simple barge-like cargo boats that could be easily built and poled, rowed or sailed appeared in New England and possibly in New York. Some of these, referred to as gundalows, were typically rectangular in plan and featured flat bottoms, inclined ends, retractable masts near the bow and rudders and tillers aft. They were well adapted for carrying lumber and hay and persisted into the late nineteenth century in some rivers. With the inauguration of canals in New York State, specialized boats based on narrow boat prototypes in Europe were introduced. Some of these found their way to the Hudson River. Flat bottomed, horse-drawn packet boats and line boats carried passengers or a mix of passengers and freight. But with a few notable exceptions, they remained in the canals. However, mule-drawn freight barges often plied the Hudson when they were gathered up in the huge steam tows of the nineteenth century and taken with their cargo to New York. These barges and scows featured specialized designs based on intended trades and the building preferences of yards all across New York and the neighboring states. Barges carrying coal were markedly different from those intended to carry perishable cargoes such as grain. They also differ depending upon the dates of policy changes on the canals (squared bows prohibited due to embankment damage) and the dates of canal expansion projects when the dimensions of the canals and the lock chambers were enlarged allowing deeper and wider barges to grow simultaneously. A number of canalboats were fitted with sail rigs for use when these barges reached the open water of large lakes and rivers where animal towing was no longer possible. Hoodledashers, powered canal barges usually towing a second, unpowered barge, became a feature of the greatly expanded NYS Barge Canal of 1915. One, the Frank A. Lowery, was abandoned in the Rondout in 1953 and remains identifiable. Many canal barges have found their way to the bottom of the Hudson and its tributaries, including a rare bifurcated and hinged Morris Canal barge from the nineteenth century. Unlike the canals, barges built for use on the Hudson River were less limited in terms of configuration or dimensions. One of the few commonalities among them was the presence of log fenders suspended from the rails along the sides. A large number of box-like barges with living cabins aft were built to carry coal in their holds. Many measured 100 feet in length and 25-30 feet in beam. Some included midship houses for collapsible masts, derrick booms and winches to facilitate loading and unloading. Rectangular scows with inclined ends were built in large numbers to carry deck loads of trap rock, sand, brick and other bulk or non-perishable freight. They often featured deck cabins for their keepers and families and bulkheads fore and aft to contain the material and separate it from the living quarters. Barge hulls were readily used for dredging equipment, pile drivers and derricks used in salvage and construction. Specialized dump scows were built by the New York Sanitation Department with trap bottoms that could release garbage and refuse when outside of New York harbor. The weathered wooden bones of scows and coal barges can be found all along the river as well as in our own Rondout Creek. A prominent derrick barge lies abandoned in Athens. The railroads were major barge builders in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Their ferries, tugs, lighters and barges and car floats (the term used for the long narrow barges that carried rail cars between terminals) were legion and referred to as the “railroad navy.” All of this floating equipment was necessary to move freight from ships to railroad terminals and to move freight and rail cars between terminals and to customers across a metropolitan region divided by rivers, bays and inlets. Among the specialized barges built by the railroads were the hundreds of covered barges built to transport perishable and high value freight throughout the New York area. These distinctive boats with scow-like hulls and boxy cabins with double barn doors on each side made their way up the Hudson on occasion. A number of them found waterfront retirement homes as shad fishing cabins and marina headquarters when no longer useful to the railroads. The Pennsy 399, built in 1942 for the Pennsylvania Railroad, has been restored and is currently docked in the Rondout. Then there were the early nineteenth century “safety barges” built to transport squeamish passengers afraid of dying in the notorious steamboat explosions or fires that characterized the early years of steam navigation. These were often double decker affairs that looked like steamboats without the paddlewheels or the stacks. A closely related barge type that appears to have grown out of the safety barge model was the hay and produce barge. These craft appear to have proliferated after the Civil War when New York City’s demand for upstate hay became insatiable. Towed in great rafts by paddlewheel towboats and later by tugboats, they were typically double-deckers with shallow draft moulded hulls, tall masts to carry stiffening stays, pilothouses and rudders. In addition to their workaday role carrying hay, livestock and produce, they were popular for inexpensive passenger excursions on Sundays. One example, the Andrew M. Church, built in New Baltimore in 1892, was 139 feet long, carried three decks and was equipped with a rudder and a pilothouse to facilitate tracking and docking. She made her inaugural voyage taking four Sunday School classes to a local picnic ground. Sometimes, these barges were rafted together and towed in pairs or even groups of four. They were still in use carrying hay in the 1930s, and a specialized version, the cattle barge, persisted even longer. Barges were also built in the nineteenth century for oyster processing and sales, chapels and even municipal bathing pools. Hospital barges appeared in the 1870s initially through the philanthropy of the Starin Line and were towed around New York harbor in good weather to offer fresh air and a change of scenery to invalid patients. Ultimately, the concept evolved into that of a floating clinic set up in disadvantaged communities. The last of these, the 1973 Lila Acheson Wallace is now docked on the Rondout Creek waiting to be repurposed. Specialized lumber barges also made an appearance with moulded hulls based on the hay barge model. They were built with aft cabins and pilothouses and appear to have carried large deckloads of lumber. Another distinctive Hudson River barge is the ice barge. Transporting the blocks of ice cut from the river during the winter months and stored in enormous white warehouses along the river shore to urban centers where refrigeration was essential, these barn like barges with rounded bows and sterns carried distinctive windmills to pump out melt water and derrick masts and booms to facilitate loading and unloading. There is no less variety in the steel barges plying the Hudson River currently. Many are specialized to carry and handle petroleum products, steel recycling, turbines, rock and dry cement. They are typically pushed by diesel tugs but on occasion they are breast towed or towed aft in the nineteenth century manner to facilitate handling and docking. Some are still named for places or members of the respective towing company families and are routinely maintained and painted with pride. Articulated tug and barge combinations (ATBs) represent a relatively recent innovation. They are designed to allow the bow of a tug to precisely fit a notch in the stern of the barge so that when underway, a single unit is created, simplifying handling while avoiding the regulations entailed in designing and operating a comparable motorship. While less visually interesting than their nineteenth century antecedents, today’s barges carry far more tonnage and operate more safely and efficiently. AuthorMark Peckham is a trustee of the Hudson River Maritime Museum and a retiree from the New York State Division for Historic Preservation. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

|

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 [email protected] Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |