History Blog

|

|

|

|

|

This one's for the film buffs AND the sailing buffs! Today's Media Monday post features the 1958 film Windjammer: The Voyage of the Christian Radich. Filmed aboard the Norwegian three-masted bark Christian Radich, "Windjammer" was filmed in the groundbreaking (and short-lived) Cinemiracle wide screen process. Long before IMAX, Cinemiracle was a strikingly immersive film experience for 1958, and Windjammer was the only feature-length film ever produced by this process.

Based on a book written by Allan J. Villiers, the film follows a crew of young Norwegian men on a sail training mission aboard the Christian Radich. The film covers a journey of 17,500 nautical miles from Norway to Madiera, the Dutch West Indies, Puerto Rico, Trinidad, Philadelphia, New York, and Boston before heading back to Oslo across the North Atlantic and around Scotland. Although the young crew of the vessel (some as young as 14) are numerous, the storyline focuses on only a few, including one boy training to be a concert pianist. The entire film runs about 2 hours and 30 minutes (including prologue and intermission). It premiered at Grauman's Chinese Theater in Hollywood April 8, 1958, and on April 9, 1958 premiered at the Roxy Theater in New York City on a curved, 40 foot high by 100 foot long screen. It needed three film projectors to synchronize the wind screen format. The screen size and curve (nearly identical to Cinerama) made the viewer feel as if they were immersed in the film. And as you'll see below, the film started out in standard format, the screen flanked by theater curtains, which were then drawn back to expose the enormous wide screen.

The film was later converted to Cinerama, which required only one projector, not three. It went on to be nominated for several awards, and was so popular in Norway that in 1959 it was seen in Oslo more times than there were people in city. You can watch the restored trailer below.

No Cinemiracle or Cinerama theaters survive today, but the Christian Radich does. Built in 1937 specifically as a sail training vessel for Norway, she remained at that post until the 1990s. Today, she is operated as a private vessel that offers sightseeing tours of coastal Norway and sail training for young people - as she originally intended.

Windjammer is available for streaming purchase on Amazon Prime. If you want to learn more about Windjammer, including the technical process, screenings, interviews with cast and crew, etc., visit here. And if you're curious about historic sailing vessels, be sure to check out our upcoming 2022 exhibit, "A New Age of Sail: The History and Future of Sail Freight on the Hudson River," Opening May 1, 2022!

If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

0 Comments

In May of 2022, the Hudson River Maritime Museum will be running a Grain Race in cooperation with the Schooner Apollonia, The Northeast Grainshed Alliance, and the Center for Post Carbon Logistics. Anyone interested in the race can find out more here "The coming sailing vessel of the future, however, is the auxiliary; no matter what her rig may be. A vessel fitted with [Electric] engines, placed aft for convenience, offers a decided advantage to navigators and one that is beginning to be appreciated. [Electric] engines [and batteries] take up a certain amount of hold space, to be sure, but the advantage gained through being able to make headway in all kinds of weather should not be undervalued. When a dead beat to windward is encountered, instead of sailing 500 miles to make 250, all that is necessary is to start the engines and plow ahead into the wind's eye. Again, in light airs, the engines can be used to advantage in decreasing the port-to-port time. If the vessel should happen to be dismasted, the engines are there to be called into service. If anchored near a lee shore with no chance of ratcheting off- Start the engines." --Modified from: Reisenberg, Standard Seamanship For The Merchant Service. New York, NY: D Van Nostrand Co, 1922. Page 17. While improvement of the early sailing auxiliary designs and capability was abandoned due to the low price of fuel in the majority of the 20th century, Wind Assist systems such as kytes, Flettner Rotors, and Wing Sails are being deployed through the EU today as a way of reducing fuel costs. Modern Wind-Assist systems can give up to 50% fuel savings on certain routes, using properly designed vessels, and some add-on modules for existing container and bulk carrier ships are showing 20-30% fuel savings. The International Windship Association has a large list of ships planning on or having already adopted these technologies. Adding traditional sailing rigs to smaller cargo vessels was experimented with extensively in the 1970s to 1980s, and showed significant fuel savings of up to 30% on some routes. This was most successful in South East Asia, where the Oil Crises of the 1970s and early 1980s had made fuel nearly unaffordable to small island states who were entirely dependent on imported diesel. The SV Kwai is a great example of this type of adaptation in the same region, operating today. This goes to show that to adopt Sail Freight, we need not abandon modern technology, we simply need to rethink and reapply it. In the world of Sustainable Shipping and Sail Freight, there are far more places to avoid carbon emissions than using sails to reduce heavy fuel oil use slightly. Starting from the idea of an auxiliary sailer as described above, but using modern motors and knowledge, one can create a near-zero carbon cargo vessel. An Australian designer and shipwright is doing just this in the realm of small cargo vessels. Designed with essentially traditional Ketch or Schooner rigs, electric motors, propeller regeneration under sail to charge the batteries, and the capability to carry containerized cargo, these modern designs are simply an update or evolution of older vessels to suit modern needs and wants, such as auxiliary engines and containerized cargo. Pairing electric motors and batteries with sailing rigs can be a highly sustainable, near-zero carbon means of sail freight shipping which retains the advantages outlined in the 1920s. This is especially true of vessels like the Electric Clippers mentioned here that are designed for as long a service life as possible. With a practical limit to the size of a traditional sailing vessel being imposed by the nature of wind power at around 12,000 tons displacement we will need a far larger number of these vessels than current, conventional, container ships to accommodate shipping requirements, but the benefits to the world in reduced carbon emissions and transport system resiliency can be astounding. Other innovations are in progress, such as entirely modern, very large sailing vessels. Neoliner is one of these, which is building a 136 meter long, 11,000 ton displacement sailing vessel of entirely modern design. The vessel is designed for RO-RO (Roll On-Roll Off) of vehicles, can carry 5,000 tons of cargo, and is also equipped with auxiliary engines. There are a few traditionalists in the Sail Freight Revival, including EcoClipper and Fair Transport, which are planning on using and making strictly sail powered vessels with no engines. However, these ships are still equipped with modern navigation and communications equipment, which is responsible for significant improvements in safety for crew and cargo. Even the traditionalists want to improve health and safety. There's no need to abandon modern technology in moving forward to a post-carbon future. There is, however, a need to recombine it with older technologies in a way which serves human purposes while respecting environmental boundaries. You can find more information on the Grain Race here. AuthorSteven Woods is the Solaris and Education coordinator at HRMM. He earned his Master's degree in Resilient and Sustainable Communities at Prescott College, and wrote his thesis on the revival of Sail Freight for supplying the New York Metro Area's food needs. Steven has worked in Museums for over 20 years. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's Note: The following is a verbatim transcription of a chapter from Spalding's Winter Sports by James A. Cruikshank, published in 1917 and part of the Ray Ruge Collection at the Hudson River Maritime Museum. Many thanks to volunteer Adam Kaplan for transcribing this booklet. This is our final installment - thank you for reading along! Perhaps in no outing of the year will the confidence and assurance of the beginner bring such unfortunate punishment as in the winter cruises over the snow and in the cold. Neglect of the simple precautions which the expert has learned to regard as absolutely necessary may bring trouble, not merely to the individual, but to the entire party. It is no small trial to find that, because some over-confident amateur has rushed off on the trip with insufficient preparation or equipment, the entire plans of the party must be changed, or perchance the individual will become the ward of the group. A severe frost-bite, a shoe too tight, an ill fitting binding of snowshoe or ski, a broken snow implement- these are generally things which can be avoided with a little anticipation and forethought. It is no joke to attempt to guide or carry home some husky amateur who has paid the penalty of foolhardiness by starting out ill-equipped; nor is it pleasant to be left alone by a sputtering fire in the heart of the snow laden woods while somebody strains to get help. One such experience will cure anybody, and it will also break up a pleasant outing and some of its friendships. The best plan on all winter outings which take the party any considerable distance from headquarters is to select and appoint a captain known to be familiar with the work in hand. His opinion should be final. He should even have the authority to refuse a place in the party to those who are not properly equipped. This is the custom among many of the oldest and strongest winter organizations of the country, whose winter outings increase in popularity and interest every year. It is important to keep tally of the number of persons in the party and to “count noses” occasionally, especially where the going is bad and when teams are taken for the return trip or for distant points. In laying out trails, care should be taken to leave marks indicating any possible deviation in the route, either by arrows drawn in the snow, paper stuck in a split stick and stood up in the trail, snow mounds, or broken branches laid across the trail not to be followed. In snowshoe work the leader should adapt his stride to the shortest member of the party. In hill climbing he should make short steps, and the following members of the party should place their snowshoes accurately in the first track so that the steps do not become ragged and useless. Among the valuable items of the equipment, for either individuals or parties, are maps of the country, a compass, drinking cups, matches, knife, extra length of rawhide for possible repairs, safety pins, length of strong rope wound around some member as a belt. A folding candle lantern will often be very useful. It is not always agreeable to make an extended stop for lunch, and many of the most enthusiastic winter cruisers carry only such lunch as can be conveniently eaten while en route. Shelled nuts, raisins, sweet chocolate, triscuit, malted milk tablets, and crackers, are some of the best quick rations. Snow should not be eaten. If thirsty, a few raisins, lime tablets or even a bit of lemon eaten with a little snow may be used. Frost bite is the special thing to guard against in most amateur winter outings. It occurs with so little warning that the best plan is for each member of the party to watch the faces and ears of others in the party and give warning. The presence of a white spot should immediately be called attention to, and remedies applied. The first aid in this case is brisk rubbing with a woolen mitten, or glove, on which fresh snow is placed. In the case of frozen parts keep in the cold air and apply only cold treatment such as snow and very cold water until color and sensation return, when warm applications may be gradually used. Vaseline or any other greases should be applied after the frozen part has been brought to normal appearance. The continued use of snowshoes when the snow is very deep and heavy may bring on Mal de Raquette, most dreaded of all the winter troubles of the far north. It is caused by unusual and severe strain upon the muscles of the lower leg. The veins become clotted by overheating and the blood is kept in the lower extremities. Sometimes the limbs swell to two or three times the normal size and turn black. The premonitory symptoms of this very serious trouble are numbness of the limbs, lassitude and exhaustion. The remedy is to bare the legs to the skin, jump in the snow and stay there until the pain is unbearable, then rub the legs upward, toward the heart, until the flow of blood sets in. When symptoms are slight, the men of the north content themselves with elevating their feet and legs above the level of their heads as they lie and smoke, in which position the blood flows back into the body. Snow-blindness is frequent among the habitual outdoor folks of the north and should be guarded against by amateurs. There is no glare in all the year so severe as the glare of the sun from ice and snow. In Switzerland, in midsummer, the glacier travelers apply burnt cork to their faces, not merely to avoid sunburn but also to save the eyes. Automobile goggles are an excellent addition to the winter equipment, or smoked glasses, which should be fastened with a cord to the person. In case neither of these things are at hand, and the glare of the sun seems likely to cause trouble to any member of the party, a very simple prevention consists of a bit of flat wood, roughly whittled into the shape of goggles, and in the middle of which a narrow slit is cut. These are the Indians’ snow-goggles. No winter outing is complete without a photographic record of its interesting episodes. From the snowshoe tumble, which is so excruciatingly funny- to the other folks- to the tracks of wild creatures in the snow, there ranges every form of pictorial possibility. The equipment, however, should be light, simple and carried in waterproof and snow proof case. A box Kodak of set focus is always ready, and has many advantages. The postal size folding camera crowds it close in winter value and has scenic uses the cheap instrument lacks. One should remember that at no time of the year is there so much white light as in a mid-winter noon, and that the early day and the late day have deceivingly small amount of white light. AuthorJames A. Cruikshank was an expert on outdoors sports during the first half of the 20th century. Born in Scotland but spending most of his life in New York, he was the editor of The American Angler magazine, Field and Stream, and wrote numerous articles for a wide variety of other magazines and newspapers throughout his career, including the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. He also published at least three books: Spalding’s Winter Sports (1913, 1917), Canoeing and Camping (1915), and Figure Skating for Women (1921, 1922). He also contributed a chapter on artificial lures to The Basses: Freshwater and Marine (1905). In addition to his writing, Cruikshank was involved in public speaking, doing talks on outdoor sports sometimes illustrated by motion pictures. An avid photographer, Cruikshank’s photos often featured in his illustrated lectures, his articles, and his books, as he encouraged readers to take their own cameras out-of-doors. He had a home in the Catskills as well as a home and offices in New York City, and in the 1930s he helped found the Hudson River Yachting Association. At one point, he managed the Rockefeller Center ice skating rink, and another in Rye, NY. His wife Alice was also an avid camper and hiker, and they often traveled together. In 1909, Alice went “viral” in newspapers around the country by being the first person to blaze a trail between Mount Field and Mount Wiley in the White Mountains of New Hampshire (James brought up the rear). James and Alice eventually moved to Drexel, PA and were vacationing in Lake Placid in July of 1957 when James died unexpectedly at the age of 88. James Cruikshank went on to publish another book, Figure Skating for Women, in 1921, and remained a steadfast supporter of women in sports and outdoor photography.

If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today! In February of 1946, tugboat crews in New York Harbor had had it. They had been trying since October, 1945 to negotiate an end to the wartime freeze on wages, to reduce hours from 48 per week to 40, to receive two weeks paid vacation per year, and perhaps most importantly, to end the practice of stranding workers in far-away ports and forcing them to pay their own way home, without success. Although the war was over, the federal government was still regulating the price of freight, which meant that shipping companies didn't want to raise wages. Frustrated, the tugboat workers struck. Starting February 4, 1946, tugboats did not move coal or fuel in the nation's busiest port. Manhattan is an island, and maritime freight played a huge role in supplying the city with fuel, food, and other supplies, as well as removing garbage by water. At the time of the strike, officials estimated the city has just a few days of reserve coal. The strike was covered in several newsreels at the time. British Pathe put together this short report on the strike: Universal put together this newsreel, sadly presented here without any sound: Newly-elected mayor William O'Dwyer did not react well to the strike. Facing a fuel shortage for one of the nation's most populous cities in midwinter was no laughing matter, but O'Dwyer implemented measures that many later deemed an overreaction to the strike. He essentially rationed fuel for the entire city, prioritizing housing for the sick and aged, but enforcing a 60 degree maximum temperature for all other building interiors, turning off heat in the subway and limiting service, shutting down all public schools on February 8, and by February 11 shutting down entirely restaurants, stores, Broadway theaters, and other recreational venues. The bright lights of Times Square and elsewhere were also turned off to conserve electricity, as illustrated in this second newsreel from British Pathe: After 18 hours of shutdown, the shipping companies and the tugboat unions agreed to end the strike and enter into third party arbitration for their contract. Tugboats started moving fuel again, and the lights turned back on. And that's the end of the story - or is it? On February 14, 1946, the New York Times published an article entitled "Lessons of the Tug Strike," whereby they largely blamed O'Dwyer for the costly shutdown. "New York tugboat workers and management have sent their dispute to arbitration after a ten-day strike that endangered life and property, cost business millions of dollars and paralyzed the whole city for a day. We may well breathe a sigh of relief and at the same time examine some aspects of this incident that offer guidance for the future," the Times wrote, and went on to ask that O'Dwyer never do that again "unless the need is clearly established." As for the tugboat workers, it would take nearly another year for the threat of a strike to fade completely. Negotiations continued throughout 1946, with little movement, until the threat of another strike emerged in December of 1946. It was avoided by additional arbitration with Mayor O'Dwyer's emergency labor board. Finally, the arbitrators won concessions from both sides, and on January 5, 1947, the New York Times reported that a settlement had been reached. The tugboat workers got their 40 hour workweek, but not the same wages as 48 hours of work. They did get an 11 cent per hour wage increase along with a minimum wage for deck hands, a five day workweek, and time and a half for Saturdays and Sundays. However, the contract was only for 12 months, and in December of 1947, another strike was on the table as workers struggled for another wage increase. The strike was averted with more concessions from the companies, including a ten cent raise, food allowances, and more. But in the fall of 1948, the contract was up again, and the specter of the February, 1946 shutdown arose as a strike was once again on the table as part of the negotiations. Strikes were common in the years following the Second World War, in nearly every aspect of American society. In particular, the Strike Wave of 1945-46 impacted as many as five million American workers across all sectors. The strikes, although sometimes effective in improving worker wages and conditions, were largely unpopular with the general public. In 1947, Congress overrode President Truman's veto of the Taft-Hartley Act, which limited the power of labor unions and ushered in an era of "right to work" laws. Learn more about the strike wave in this podcast from the National WWII Museum. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's Note: Editor's Note: The following is a verbatim transcription of a chapter from Spalding's Winter Sports by James A. Cruikshank, published in 1917 and part of the Ray Ruge Collection at the Hudson River Maritime Museum. Many thanks to volunteer Adam Kaplan for transcribing this booklet. There is no reason why the average country club of the northern part of the United States or Canada should close up shop and hibernate during the winter. Some few pioneering clubs have already demonstrated that there is as much interest in sports of the winter as in those of the summer, and they are keeping open house all the year round. Some of the methods which are employed to interest the membership and provide what that membership desires in the way winter pastimes may be of value to other organizations. A toboggan slide will interest a very large proportion of the membership and can generally be managed on such a basis as to pay for itself, or at least for its maintenance. This has been the experience of the famous Ardsley Country Club, Ardsley, N.Y., which even went to the extreme of bringing to its club a recognized tobogganing expert of Canada, who directed the construction of its slide, and manages the rental of the toboggans and the maintenance of the slide. Almost any hilly country is adapted to the erection of a toboggan slide, and with a slight artificial stand with which to create initial impetus, a fine slide can be arranged. In small towns and sparsely settled communities it is often possible to arrange with the authorities for the use of one of the roads for certain hours or certain days, and with the placing of watchers at cross roads some of the magnificent sport which Switzerland enjoys in the way of coasting ought to be possible. The Lake Placid Club in the Adirondacks starts its toboggan slide from the roof of the golf house, which offers a suggestion other clubs may care to follow. Wooden troughs can be erected to carry the slide across brooks or gulleys, then the natural resources of the ground and the snow utilized again. The famous Swiss runs are first banked with snow and then water, which is piped all along the run, is sprayed upon the snow banks. There is tremendous side thrust to a heavily loaded toboggan or bob-sled going at great speed around a curve, and the construction of the slide should be strong and safe. The construction of an ice rink is easy where there is either a small brook nearby or water piped to the vicinity. Tennis courts are often used as the foundation of ice rinks, and serve admirably, but the water must be drawn off at the first approach of spring or the field will remain soft for an uncomfortably long time. The better plan is to have a special field for the ice rink, lay clay foundation and make side walls of 8 or 10 inches in height. When the first cold weather comes spray the field with a fine rose spray flung high in the air so that it freezes immediately upon touching the ground. Do not flood any skating field unless you want shell ice, at least not in the vicinity of New York or any place of similar average temperature. Of course, where there is a running brook, the building of a low dam, often merely 2 or 3 feet in height, will serve to back the water up over lowlands and provide a very satisfactory skating field during steady cold weather. A flood-gate should be put in the dam, however, so as to raise the level at any time, and thus create a new skating surface and get rid of the snow. It is most important that when snow has fallen on a skating field it must not be walked over, since the hardened footprints will remain and form annoying lumps, even after the balance of the snow has melted. It is much better to remove all snow as it falls, however, unless the size of the field is too large. Skating on ice which has been formed by spraying onto clay bottom may begin when 1 inch of ice has been formed. Where ice forms over water, the following thicknesses are necessary for various weights; 2 inches will sustain a man or properly spaced infantry; 4 inches will sustain a horse; 6 inches will sustain crowds in motion; 8 inches will sustain men, carriages, and horses; 15 inches will sustain passenger trains. Ice which is disintegrated by the action of salt water loses nearly 50 per cent. of its sustaining strength. It is now generally calculated that the large free skating coming into popularity in this country, and known as the International style, requires a rink of about 25 by 50 feet for a dozen persons. AuthorJames A. Cruikshank was an expert on outdoors sports during the first half of the 20th century. Born in Scotland but spending most of his life in New York, he was the editor of The American Angler magazine, Field and Stream, and wrote numerous articles for a wide variety of other magazines and newspapers throughout his career, including the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. He also published at least three books: Spalding’s Winter Sports (1913, 1917), Canoeing and Camping (1915), and Figure Skating for Women (1921, 1922). He also contributed a chapter on artificial lures to The Basses: Freshwater and Marine (1905). In addition to his writing, Cruikshank was involved in public speaking, doing talks on outdoor sports sometimes illustrated by motion pictures. An avid photographer, Cruikshank’s photos often featured in his illustrated lectures, his articles, and his books, as he encouraged readers to take their own cameras out-of-doors. He had a home in the Catskills as well as a home and offices in New York City, and in the 1930s he helped found the Hudson River Yachting Association. At one point, he managed the Rockefeller Center ice skating rink, and another in Rye, NY. His wife Alice was also an avid camper and hiker, and they often traveled together. In 1909, Alice went “viral” in newspapers around the country by being the first person to blaze a trail between Mount Field and Mount Wiley in the White Mountains of New Hampshire (James brought up the rear). James and Alice eventually moved to Drexel, PA and were vacationing in Lake Placid in July of 1957 when James died unexpectedly at the age of 88. Tune in next week for the final chapter!

If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!  Crew of the steamboat Mary Powell posing on deck. 1st row: Fannie Anthony stewardess; 4th from left, Pilot Hiram Briggs; 5th, Capt. A.Eltinge Anderson (with paper); 6th Purser Joseph Reynolds, Jr. Standing 3rd from left: Barber(with bow tie). Other crew members unidentified. Donald C. Ringwald Collection, Hudson River Maritime Museum. The Mary Powell was one of the longest-serving and most famous of the Hudson River passenger steamboats. She was in operation from 1861 to 1917, and many of her crew were Black and African American. Although it is not clear whether or not Black or African American passengers were allowed to travel aboard the Mary Powell, many of them did work aboard the boat, mostly restricted to lower-paying jobs such as deckhands, waiters, and boilermen. Some steamboats did have Black stewards, and the Mary Powell had Fannie M. Anthony – the Black stewardess who managed the ladies’ cabin for decades, but it is unclear if any of the stewards listed in the Mary Powell crew records were African American or not. However, there were enough Black employees working aboard the Mary Powell for them to form their own club - The Mary Powell Colored Employees Club. The little evidence we have of the Mary Powell Colored Employees Club comes from newspaper articles, primarily organized around the annual cake walk the club put on each year between at 1909 and 1917. Cake walks were a style of dance popular in the 1890s and 1900s among Black communities, and often co-opted by Whites. Originating in enslaved communities as a mockery of the formal dances, primarily the Grand March, of Southern plantation owners, athletic variations invented by African and African-American dancers lent themselves well to competitions. Cake walks generally had two variations – graceful and athletic versions designed for Black audiences, and wild caricatures designed for White audiences, often in conjunction with minstrel shows. These two historic films illustrate the differences. The first shows Black dancers in formalwear, focused on elegance. The second features those same dancers in exaggerated dress, performing a comedic routine, likely for a White audience. In 1909, the Kingston Daily Freeman announced the first annual cake walk of the “colored employees of the steamer Mary Powell.” About a month later, on September 23, the Freeman reported on the success of the cakewalk. Held at Michel’s Hall (located at 53 Broadway), “The hall was filled with friends of the Powell’s colored employes [sic], besides many others composing the officers and crew of the boat.” This mention of other officers and crew seems to imply that the event may have been integrated. The article also lists the officers of the Mary Powell Colored Employees Club:

Prizes were offered for the best dancers, and first prize went to John Schoonmaker of Kingston, NY and Medina Schoonmaker of Poughkeepsie, NY. “Second honors were taken by Ott Overt and Maude Overt of Poughkeepsie.” The Poughkeepsie Evening Gazette also reported on the cake walk, likely because residents of that city placed in the contest. The cake walk continued in 1910, held on September 15, again at Michel’s Hall. This time the walk featured Professor Butler’s orchestra from New York City, as well as “several professional cake walkers from New York, Newburgh and Poughkeepsie.” No articles appear for the 1911 dance, but in October of 1912 something curious happened – two different dances for Mary Powell employees occurred, just days apart. On October 2, 1912, the Mary Powell Colored Employees Club held their “fourth annual ball and cake walk” at Michel’s Hall, with Professor Butler’s orchestra and “two couples of professional cake walkers.” But on October 3, 1912, the Kingston Daily Freeman announced “The first annual dance of the deck hands of the Mary Powell will be held in Washington Hall on Saturday evening.” On the appointed day, October 5, the Freeman reported: “The Mary Powell deck hands will hold their annual dance in Washington Hall this evening. This dance has always been one of the most popular of the season and it is expected that this year will be no exception.” Were these the same dance? Likely not – one took place on October 2nd in Michel Hall, located at 53 Broadway in Kingston. The other took place on October 5th in Washington Hall, located at 110 Abeel Street in Kingston. Was one a dance for the Black employees and the other a dance for White employees? Did the person writing the October 5th article confuse the deck hands’ dance with the Mary Powell Colored Employees Club dance? Or did the deck hands really have dances before 1912? It seems likely that 1912 was the first year of the deck hands’ dance, corroborated by an advertising poster from 1912 confirming that as the first year. Notably, future Mary Powell captain Arthur Warrington is listed as the President of the Mary Powell Deck Hands. Lawrence Dempskie is listed as Vice-President, John Malia as Treasurer, Frank Sass as Secretary, and George Brown as chair of the Floor Committee. Note also the reduced price for ladies. There is almost no further mention of either club or dance, except for one reference in the New York Age, a Black newspaper based in New York City. On September 20, 1917, the reported, “The annual dance given September 12 by the young men of the steamer Mary Powell was largely attended. Good music contributed to an enjoyable evening. Many from out of town attended.” This is almost certainly referencing the Mary Powell Colored Employees Club event. 1917 was the last season of the Mary Powell – she remained out of service in 1918 and was sold for scrap in 1919. To learn more about Black and African American workers aboard the Mary Powell, check out our previous blog posts on Fannie M. Anthony, the Black Glee Clubs of the Steamboats Mary Powell and Thomas Cornell, and check out our online exhibit about the Mary Powell. For more information about Black history on the Hudson River and in the Hudson Valley, check out our Black History blog category for more to read. AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson is the Director of Exhibits & Outreach at the Hudson River Maritime Museum. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Media Monday: How a French Nobleman Got a Wife Through the New York Herald Personal Columns (1904)2/14/2022 Happy Valentine's Day! Todays' Media Monday post is a light-hearted silent film based on a true story, and set at a famous Hudson River landmark. In 1904, the Edison Manufacturing Company produced this short silent film, "How a French Nobleman Got a Wife Through the New York Herald Personal Columns." Based on a real story, the picture opens with a "Personal" advertisement which actually appeared in the New York Herald of August 25th, 1904. It reads: "Young French Nobleman, recently arrived, desires to meet wealthy American girl; object matrimony; will be at Grant's Tomb at 10 this morning, wearing boutonniere of violets." Housed at the Library of Congress, the film follows a young French nobleman whose idea to place a personal in the newspaper in order to find a wealthy wife, whom he will meet at Grant's Tomb, doesn't quite go as planned. Hilarity ensues. The Library of Congress describes the film: The first scene shows the young "Nobleman" in his dressing room. He picks up the "Herald," and finally locates his "ad" with evident satisfaction. He then fastens a large bunch of violets to the lapel of his coat and departs for rendezvous. The next scene shows the "Nobleman" at Grant's Tomb, pacing impatiently back and forth. Soon a handsome young lady passes him, and seeing the violets, mutual recognition quickly follows. Another lady soon arrives, and others in rapid succession until the young Frenchman is completely surrounded. He finally escapes and runs for his life down the Riverside Drive, pursued by a dozen or more of his fair would-be captors, a stout lady in white bringing up the rear. He leads the girls a merry chase over sand banks, fallen trees, through bushes, over rail fences, and finally escapes, as he thinks, by wading into a pond up to his waist. The girls finally reach the pond and stand on the bank, imploring him to come ashore. But the Frenchman pays no heed to them. Finally the stout lady, who has been last throughout the entire race, arrives upon the scene, and without hesitating for an instant she dashes into the water and finally captures first prize and a titled husband in the bargain, again proving the old adage that "The race is not always to the swift." We hope you enjoyed this fun silent film, and have a Happy Valentine's Day! If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's Note: The following is a verbatim transcription of a chapter from Spalding's Winter Sports by James A. Cruikshank, published in 1917 and part of the Ray Ruge Collection at the Hudson River Maritime Museum. Many thanks to volunteer Adam Kaplan for transcribing this booklet. Where winter is at all reliable, and snow and ice can be confidently counted upon in advance, no outdoor festival of the whole year will furnish such invariable delight as the winter carnival. There seems to be some unique quality about winter which stimulates to merriment and enthusiasm. It is something more than the scientific fact that one-seventh more oxygen is found in the cold air of winter than in the warm air of summer. The same group of young people will reveal in winter depths of fun and prankish tendencies unsuspected by any actions of the summer time. Staid matrons have been known to try the turkey trot on snowshoes who never tried it anywhere else; and contributing thereby entertainment which neither they nor their friends ever before suspected them capable of. Nobody stands about in wallflower pose when the winter carnival is on. Canada started the world on the winter carnival. And then, because some of the thoughtless folks whom she desired as settlers and immigrants got the mistaken idea that Canada was a land of snow and ice, she suddenly dropped the thing. Now, with a better knowledge of her magnificent climate spread abroad all over the world, she has sensibly gone back to the enjoyment of those delightful and exhilarating winter pastimes which no other people on earth know so well how to arrange and participate in, and she again welcomes the seeker after winter joys. There is inspiration and information for every lover of winter joys in even the briefest visit to the Dominion during the couple of cold months of the year. Perhaps the presence there of so much of the French gayety and vivacity reveals the secret of her wonderful success in the carnivals of winter. But Canada is no longer the exclusive authority upon the enjoyment of winter. Switzerland, Norway, and some parts of the United States are but little behind in fostering the winter carnival. it is an unquestioned truth that nowhere in the world is there larger interest in winter pastimes than in the United States. Country clubs, outdoor organizations of all kinds, even groups of serious folks interested primarily in the betterment of the locality or the town in which they live, and in some few cases town governments themselves, are now aware of the delightful vacations which may be enjoyed by merely taking advantage of the local presence of cold weather and snow. On Long Island, New York State, in recent years there has been an illustration of this spirit to the extent of closing the schools when the big bob-sled races with the neighboring town take place, just as in sunny California the schools are often closed when snow falls in order to let the youngsters revel in its unusual beauty. All a big winter carnival needs, given the right sort of winter, is a moving spirit. Let somebody start the thing and the expression of interest will be immediate, and support will be generous. The very novelty of the affair will attract attention and draw people. And once it has been successfully carried out there will be large demands for its repetition. The famous ice palaces of Montreal, with their accompanying picturesque carnivals, did not die for lack of interest or patronage; they were killed intentionally, because they carried a wrong impression to the balance of the world. In time they will be revived. An ice palace sounds elaborate and difficult, but it need be neither. Blocks of ice or a foundation of a wooden structure upon which streams of water are played may be employed to create a structure big enough for the sport of attack and defense by armies on snowshoes and skiis, carrying torches and burning red fire. Exceedingly interesting effects can be obtained at very slight expense, providing of course that the local weather man can be relied upon to furnish his part in the program. There may be moonlight snowshoe tramps over the hills, snowshoe races where start and finish are in front of a grand-stand, or in the center of a rink, where folks can keep moving, ski races and ski coasting, skating exhibitions, costume skating with prizes for the best costume representative of winter; skating races, couple skating in fancy movements or speed contests, fancy dancing on skates, individual and couple; parade of decorated sleighs, floats, sleds, or toboggans; parades of snowshoers, ski runners, and skaters in costume. Any number of most interesting events can be run off on an ice field, such as hoop races, wheelbarrow races, potato races, snow shovel races, where the men drag the girls one-half the distance and the girls drag the men the other half; night-shirt races, where the girls aid the men to get into a night-shirt, the men skate a short distance and then the girls aid them to get out of the night-shirt; necktie and cigarette races in similar fashion; ski races, where the men or women are drawn by horses; snowshoe obstacle races, getting through a barrel, over a fence, climbing a rope ladder; toboggan races, in which two persons sit on the toboggan and propel it by hands or feet over the ice; and lanterns of all kinds everywhere, electric illumination. If it can be arranged, colored fire, torches, toboggans rigged with tiny batteries and carrying individual insignia and emblems, costumes similarly lighted, topped off by the moonlight. AuthorJames A. Cruikshank was an expert on outdoors sports during the first half of the 20th century. Born in Scotland but spending most of his life in New York, he was the editor of The American Angler magazine, Field and Stream, and wrote numerous articles for a wide variety of other magazines and newspapers throughout his career, including the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. He also published at least three books: Spalding’s Winter Sports (1913, 1917), Canoeing and Camping (1915), and Figure Skating for Women (1921, 1922). He also contributed a chapter on artificial lures to The Basses: Freshwater and Marine (1905). In addition to his writing, Cruikshank was involved in public speaking, doing talks on outdoor sports sometimes illustrated by motion pictures. An avid photographer, Cruikshank’s photos often featured in his illustrated lectures, his articles, and his books, as he encouraged readers to take their own cameras out-of-doors. He had a home in the Catskills as well as a home and offices in New York City, and in the 1930s he helped found the Hudson River Yachting Association. At one point, he managed the Rockefeller Center ice skating rink, and another in Rye, NY. His wife Alice was also an avid camper and hiker, and they often traveled together. In 1909, Alice went “viral” in newspapers around the country by being the first person to blaze a trail between Mount Field and Mount Wiley in the White Mountains of New Hampshire (James brought up the rear). James and Alice eventually moved to Drexel, PA and were vacationing in Lake Placid in July of 1957 when James died unexpectedly at the age of 88. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

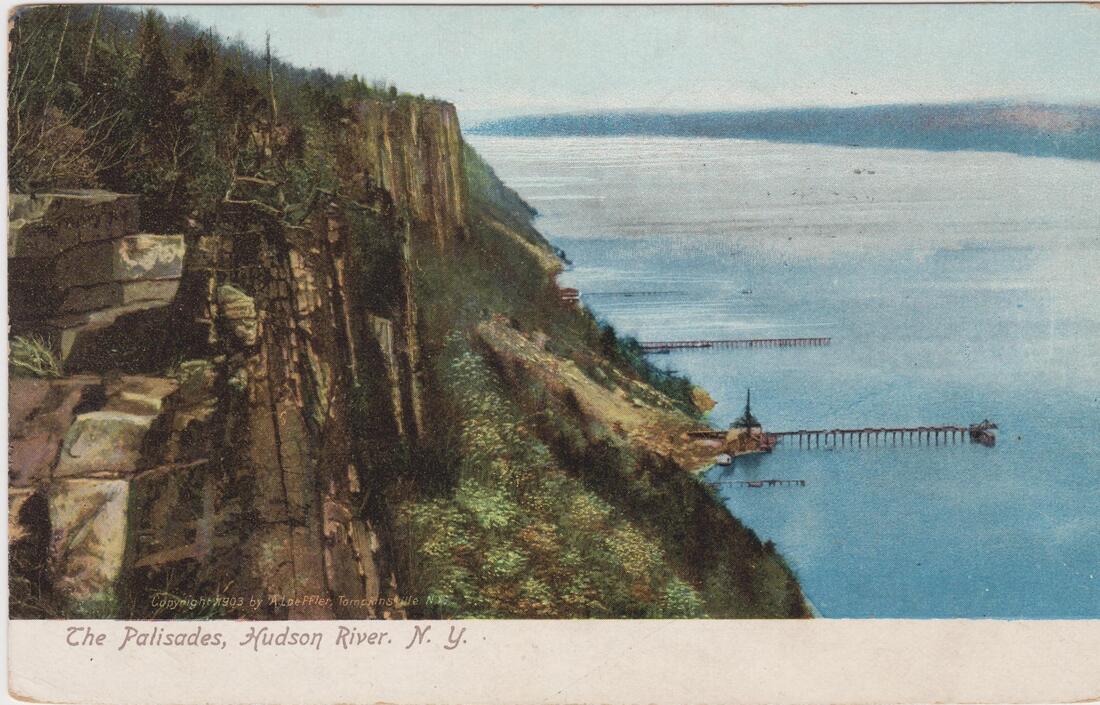

Tonight the museum will welcome Wes and Barbara Gottlock to discuss their book Lost Amusement Parks of the Hudson Valley as part of the Follow the River Lecture Series. So we thought we'd revisit some of the stories of amusement parks and steamboat landings on the Hudson River we've already published here on the History Blog. Follow the links in the introductions below to read more about each park.  Postcard of Kingston Point Park, featuring the island bandstand and rental boats. Hudson River Maritime Museum Collection. Postcard of Kingston Point Park, featuring the island bandstand and rental boats. Hudson River Maritime Museum Collection. Kingston Point Park Kingston's own local amusement park, Kingston Point Park was built by Samuel Coykendall, owner of the Cornell Steamboat Company and Ulster & Delaware Railroad. It featured a merry-go-round with a barrel piano (which is now in the museum) along with walking paths, a Ferris wheel, boat rentals, and other attractions. The main point was to serve as a landing for the Hudson River Day Line, and trains and trolleys would whisk passengers to Kingston and the Catskills. Kingston Point Park also featured prominently in 4th of July celebrations in the past.  Hudson River Day Line steamer "De Witt Clinton" approaching Indian Point Park in foreground, circa 1923. From the Donald C. Ringwald Collection, Hudson River Maritime Museum. Hudson River Day Line steamer "De Witt Clinton" approaching Indian Point Park in foreground, circa 1923. From the Donald C. Ringwald Collection, Hudson River Maritime Museum. Indian Point Park Formerly a farm, Indian Point Park was purchased specifically as a destination park for the Hudson River Day Line to rival that of Bear Mountain. It was later converted into a nuclear power plant.  Postcard of steamboat docks at the Palisades, Hudson River Maritime Museum Collection. Postcard of steamboat docks at the Palisades, Hudson River Maritime Museum Collection. Palisades Interstate Park The creation of the Palisades Interstate Park was due in large part to the work of women. The Palisades had long been a major landmark for any Hudson River mariner. Elevators were used in the late 19th century to get visitors from their steamboats at water level up to the park on top of the cliffs. Escaping Racism Amusement parks and picnic groves on the Hudson River could also be an escape. So in honor of Black History Month, we're re-sharing this wonderful article on how Black New Yorkers used steamboat charters to area parks to escape the prejudice and racism of the 1870s. Lost Amusement Parks of the Hudson Valley There's still time to join us for tonight's lecture! Register now. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

This week is the 80th anniversary of the destruction of the S.S. Normandie. On February 9, 1942, the S.S. Normandie, recently renamed the U.S.S. Lafayette, caught fire as civilian shipbuilders were trying to retrofit her as a troop transport. The Normandie was the pride of the French ocean liner fleet. Built in 1935, she was the largest and fastest and most luxuriously appointed of the new ocean liners. But when war broke out in Europe she was in New York Harbor. When France declared war on Germany on September 3, 1939, the Normandie was held by the U.S. government in New York Harbor. Still owned and crewed by the French, she was not allowed to leave. On December 12, 1941, just five days after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Normandie was officially seized by the U.S. government, and on December 27th she was transferred to the U.S. Navy, who re-christened her the U.S.S. Lafayette and began work on converting her to a troop transport. In the first class lounge, where varnished woodwork and flammable life jackets were still in place, sparks from a welding torch lit a stack of life jackets on fire. Sadly, the Normandie's complicated fire suppression system had been disconnected during the process, and the hoses brought by New York City firefighters would not fit the French connections. The blaze aboard the Normandie could not be stopped, and she rolled and sank at dock. Despite an extraordinarily expensive salvage operation in August of 1943, the righted Lafayette had sustained too much damage to be easily repaired, and both war materiel and labor were short. The Lafayette was never repaired and sat in dry dock for the remainder of the war. She was officially stricken from Naval records in the fall of 1945, and the French didn't want her either. Some attempts were made by private individuals to save her, but none were successful. She was scrapped at Port Newark, NJ between October, 1946 and December, 1948. Despite this tragic end, many of her most beautiful interiors and artwork were saved and now reside in private collections and at museums around the world, including at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Her whistle eventually ended up at Pratt Institute, and was used in the New Year's Eve celebrations until recently. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

|

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 [email protected] Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |