History Blog

|

|

|

|

|

Editor’s Note: Mingulay is the second largest of the Bishop's Isles in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland. Located 12 miles (19 km) south of Barra The Minch also called North Minch, is a strait in north-west Scotland, separating the north-west Highlands and the northern Inner Hebrides from Lewis and Harris in the Outer Hebrides. The Lower Minch also known as the Little Minch, is the Minch's southern extension, separating Skye from the lower Outer Hebrides: North Uist, Benbecula, South Uist, Barra etc. It opens into the Sea of the Hebrides. The Little Minch is the northern limit of the Sea of the Hebrides. The Longest Johns are a Bristol based, a cappella folk music band, born out of a mutual love of traditional folk songs and shanties. https://www.thelongestjohns.com/ Mingulay Boat Song - The Longest Johns Heave-'er-ho boys, let her go boys, Swing her head 'round into the weather, Heave-'er-ho boys, let her go boys, Sailing homeward to Mingulay. What care we though, wide the Minch is? What care we, boys, for windy weather? When we know that, every inch is Sailing homeward to Mingulay. Heave-'er-ho boys, let her go boys, Swing her head 'round into the weather, Heave-'er-ho boys, let her go boys, Sailing homeward to Mingulay. Wives are waiting, by the pier head, Gazing seaward from the heather; Bring her round boys, then we'll anchor, 'Ere the sun sets on Mingulay. Heave-'er-ho boys, let her go boys, Swing her head 'round into the weather, Heave-'er-ho boys, let her go boys, Sailing homeward to Mingulay. Ships return now, heavy laden, Mothers holding bairns a crying, They'll return yet, when the sun sets, Sailing homeward to Mingulay. Heave-'er-ho boys, let her go boys, Swing her head 'round into the weather, Heave-'er-ho boys, let her go boys, Sailing homeward to Mingulay. Heave-'er-ho boys, let her go boys, Swing her head 'round into the weather, Heave-'er-ho boys, let her go boys, Sailing homeward to Mingulay. Thanks to HRMM volunteer Mark Heller for sharing his knowledge of Hudson River music history for this series. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

0 Comments

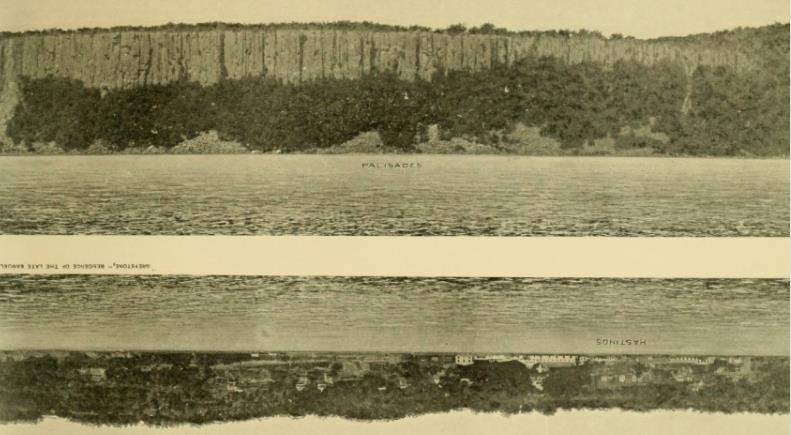

During the summer of 1884, Black veterans of the Civil War gathered on piers in Manhattan and what was then the independent city of Brooklyn. The steamboat John Lenox pulled up, towing a barge, and soldiers who served in a battalion named for abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison climbed aboard along with their families. This flotilla steamed through the New York Harbor and up the Hudson River, landing at a spot on the New Jersey banks that was called Excelsior Grove.[1] The veterans could spend the day swimming, hiking towards the Palisades rock formations that towered above, picking pimpernel flowers and wild strawberries, resting in the shade under oak and tulip trees, and listening to music.[2] Chatting with former comrades in arms and practicing military drills, Black soldiers remembered fighting in the battles that ended slavery.[3] This was one of many “excursions” to give city people without much spare change the chance to escape for a day from their dense and crowded urban neighborhoods. Getting out of the city was more than a matter of relaxation and recreation during this era, when most believed that bad smells were what made them sick.[4] Urban sanitation systems had not caught up with the rising population and rank odors wafted from overflowing outhouses and piles of uncollected garbage that festered in the streets.[5] On the decks of steamboats and in leafy waterfront groves, city people breathed deeply, hoping that the fresh air would fortify their weary bodies. At least sixty-nine lush excursion destinations with cool breezes, refreshing shade, and gorgeous views opened within a forty-nine mile radius of lower Manhattan between 1865 and 1900. This map shows the approximate locations of excursion groves that I have found. Everyone who lived in the densest, most impoverished, and least sanitary parts of the city yearned for a change of air and scenery, but excursions were especially meaningful to Black New Yorkers during the tense Reconstruction Era. While people of African descent were working to transform emancipation into an opportunity to finally secure full political and social equality, white neighbors adapted white supremacy for a nation without slavery. In New York, Black people faced harassment by the police, severe economic discrimination, and violence at the polls.[6] Intimidation and threats met them in the city’s parks, where they tried to claim their equal right to public space.[7] “Sable soldiers” were “drilling (in the dark) in one of our public squares,” reported the New York Herald in 1867. It was not safe to display Black “martial glory” in the parks except under the protective cover of nightfall because many white men considered military service to be their exclusive honor.[8] But outside the city in places like Excelsior Grove, soldiers like those who served in the William Lloyd Garrison Post No. 107 could wear their uniforms with pride, in safety. On chartered steamboats and in privately rented groves, Black New Yorkers could enjoy blooming landscapes together, away from the judgmental eyes and clenched white fists that greeted them whenever they went outdoors in the city. Excursions offered Black people the chance to breathe—and not just the fresh air that was scarce in Manhattan.  Excursionists came from one of the densest and most polluted spots on the planet to experience this scenery near Dudley’s Grove on the New York side of the Hudson and Excelsior and Alpine Groves on the New Jersey banks. Wallace Bruce, Panorama of the Hudson (New York: Bryant Union Publishing Co., 1906) New Yorkers of African descent were able to access these getaways starting in the 1870s because at least some white owners of steamboats and groves would accommodate any party with money to spend. These entrepreneurs got rich as excursionists bought cheap refreshments and pooled their pennies to rent the leafy grounds and the flotillas that carried them there. Orville Dudley was one of the businessmen whose eagerness for profit outweighed his racism when he decided whether or not to rent his grove in Hastings-on-Hudson to city people of African descent. A Black social club called the Green Horns visited Dudley’s Grove in August of 1870 and the Bethel African Church arrived the following summer. Dudley used the worst racist slur to describe these excursionists in his recordkeeping book. He called one party “a mean lot” and wrote of the other, “rough don't want them again.”[9] But Dudley loved money and Black people from the city had it, so he continued renting the grove to their excursion parties.[10] By the 1880s, Black churches, militia companies, and mutual aid associations visited destinations owned by other entrepreneurs too, like Excelsior and Riverside Groves and Iona Island.[11] Excursions opened a previously closed window for Black New Yorkers eager to get out of doors and out of the city. During the early nineteenth century, people of African descent were not welcome to join white patrons who gazed at flowers, ate ice cream, and sipped alcohol in the shade at commercial “pleasure gardens” in what was then the outskirts of New York.[12] Black entrepreneurs tried to open their own gardens in the 1820s, but faced racism on top of the usual business risks of bad weather and fire. The police ordered the closure of one of the gardens, while three others lasted for just one summer.[13] Near mid-century, beer gardens began opening in forested spots of upper Manhattan, but German American proprietors kept people of African descent out, decorated the grounds with racist imagery, and hosted offensive minstrel shows, where white actors with darkened skin performed gross stereotypes. By excluding and ridiculing people of African descent, these immigrant entrepreneurs—who themselves faced bias and prejudice in a nativist society—shored up their own access to white privilege.[14] After the turn of the century, amusement parks like Coney Island often had segregated facilities and were full of racist games like “African Dodger” and “Kill the Coon,” which beckoned visitors to throw balls at the heads of employees who were either Black or wearing blackface.[15] But between the eras of commercial gardens and amusement parks, steamboat excursions offered Black New Yorkers a rare chance to escape from the city with safety and dignity. In green refuges along the Hudson, Black residents of the metropolitan area strengthened social and political ties. New York’s Black community was growing at a rate more than double that of the white population in the 1870s, fueled in part by migrants fleeing white terrorism in the South.[16] But white supremacy shaped northern cities too, so Black New Yorkers who could not count on equal access to goods and services created their own institutions to care for one another, fundraising for these efforts by holding excursions. The Good Samaritan Home Association, for example, financed mutual aid work by selling fifty-cent tickets for an excursion to Dudley’s Grove. Funds raised at this grove also supported the Progressive American, an autonomous Black newspaper that offered a counter voice to the white supremacist media of the time.[17] Excursions for churches, militia companies, and social clubs stopped in New York and Brooklyn, uniting newcomers with longtime residents of both cities to build a metropolitan Black community.[18] Excursions forged connections between people of African descent at an important political turning point. Municipal leaders had rarely considered people of African descent as constituents before the Fourteenth Amendment made Black Americans citizens in 1868 and then the 1870 ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment promised all male citizens the right to vote.[19] Excursions helped consolidate the Black community as unprecedented access to the ballot box presented new opportunities to shape urban politics. Excursions were further politicized because Black leisure was controversial in a society rooted in slavery. Myths that people of African descent were devious, sneaky, and born to work circulated widely to justify an institution that relied on surveillance, control, and forced labor. During the Reconstruction Era, Black Americans who seized chances to leisure resisted the ideology that had rationalized slavery. By going on excursions, Black residents of New York, Boston, Wilmington, and Washington, D.C. insisted that they were deserving of pleasure, relaxation, comfort, and ease.[20] Whites responded by doubling down on the trope that people of African descent were dangerous when left to their own devices.[21] Along with racist images, stories, and performances, newspaper coverage of excursions made the case against Black leisure. Black excursions rarely made the news unless something went wrong.[22] Plenty of excursions passed peacefully, but white readers eagerly consumed sensationalized news of violence. The New York Times cast an 1887 Good Samaritan Home excursion as a scene of chaos, where “the razor went flashing through the air, the beer mug rose on high, a cane whirred overhead, and then the blood flowed.”[23] A score of other papers published their own accounts of the damage wrought by these “Implements of War” as the steamboat chugged away from Dudley’s Grove, back towards the city.[24] But this “riot lasted” for only ten minutes, admitted the Times, while the Tribune called the event “almost a riot,” rather than a full blown rebellion.[25] Newspapers exaggerated scuffles on excursions for white readers ready to believe that people of African descent had violent tendencies.[26] As Black excursionists left urban hardships behind, racist ideology followed in their wake. Despite biased coverage, excursions offered Black residents of the metropolitan area some respite from the intense racism that they experienced in daily life. Boarding steamboats with members of their growing community, excursionists traded provocations by white neighbors and harassment by the police on dusty and filthy urban streets for verdant views, salty breezes, and the dignity of autonomous Black spaces. Excursions posed a stark contrast to Manhattan, both in terms of environment and atmosphere. For Black people navigating white supremacy in a dense, polluted, and divided city, the Hudson River was a pathway towards relief that was all too brief. ENDNOTES: [1] “Fight at a Picnic,” New York Times, August 29, 1884, 5. [2] Details of Excelsior Grove’s environment come from “The Children’s Excursions,” New York Times, June 23, 1873, 8. [3] On veterans getaways, see C. Ian Stevenson, Vacationing with the Civil War: Maine’s Regimental Summer Cottages,” Civil War History 63, no. 2 (June 2017): pp. 151-180. [4] For the perceived ill effects of bad smells on health, see Melanie A. Kiechle, Smell Detectives: An Olfactory History of Nineteenth-Century Urban America (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2017). [5] Martin V. Melosi, Garbage in the Cities: Refuse, Reform, and the Environment (Homewood, IL: Dorsey Press, 1981); David Stradling, The Nature of New York: An Environmental History of the Empire State (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2010). [6] David Quigley, “Acts of Enforcement: The New York City Election of 1870,” New York History 83, no. 3 (Summer 2002): 271-292; Craig Steven Wilder, In the Company of Black Men: The African Influence on African American Culture in New York City (New York: New York University Press, 2001); Khalil Gibran Muhammad, The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2010). [7] For police harassment of Black parkgoers, see “One Policeman’s Deserts,” New York Herald, July 3, 1891, 9. [8] “A Negro Regiment” New York Herald, August 26, 1867, 7. For white opposition to Black soldiers during the Civil War, see Eric Foner, The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2010), 202, 214-215, 250-251. [9] Orville Dewey Dudley’s Daybook for Dudley’s Grove, Hastings Historical Society, Hastings-on-Hudson, August 22, 1870, August 10, 1871. [10] “Boss Tweed’s Butler Robbed,” September 15, 1872, 10; “Westchester County,” New York Times, September 14, 1879, 5; “Arraigned on the Charge of Murder,” New York Times, September 25, 1877, 8. [11] “A Colored Lad’s Suicide, New York Times, July 9, 1885, 2; “A Negro Picnic,” The Auburn, July 22, 1887, 1; “Bound for Riverside Grove,” Brooklyn Daily Standard Union, August 16, 1888, 2; “They Had a Nice Time,” New York Times, July 27, 1888, 5. [12] “Vauxhall Garden,” New-York American for the Country, May 4, 1826, 2. [13] “African Amusements,” National Advocate, September 21, 1821, 2; Marvin McAllister, White People Do Not Know How to Behave at Entertainments Designed for Ladies & Gentlemen of Colour: William Brown’s African and American Theater (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2003); “NICHOLAS PIERSON,” Freedom’s Journal, June 8, 1827; “MEAD GARDEN,” Freedom’s Journal, April 28, 1828. [14] For the transformation of European immigrants from racial others to privileged whites, see Noel Ignatiev, How the Irish became White (New York: Routledge, 1995); Thomas A. Guglielmo, White on Arrival: Italians, Race, Color, and Power in Chicago, 1890-1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004). [15] David E. Goldberg, The Retreats of Reconstruction: Race, Leisure, and the Politics of Segregation at the New Jersey Shore, 1865-1920 (New York: Fordham University Press, 2017), 3-9; “Gambling at North Beach,” New York Times, August 2, 1897, 1; Jon Sterngass, First Resorts: Pursuing Pleasure at Saratoga Springs, Newport & Coney Island (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001), 105. Kara Schlicting recovers a Black entrepreneur’s many efforts to establish an amusement park in the East River and on the Long Island Sound for people of African descent, but racism blocked him at every turn. Kara Murphy Schlicting, New York Recentered: Building the Metropolis from the Shore (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019). [16] Graham Russell Hodges, Root & Branch: African Americans in New York & East Jersey, 1613-1863 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999), 270. [17] “Boss Tweed’s Butler Robbed,” September 15, 1872, 10; “Westchester County,” New York Times, September 14, 1879, 5; “Arraigned on the Charge of Murder,” New York Times, September 25, 1877, 8. [18] “A Negro Picnic,” The Auburn, July 22, 1887, 1. [19] When New York State legislators enacted universal male suffrage in 1821, they added a qualification that required Black men to own a large amount of property in order to access the ballot. By 1840, only 90 Black men could vote out. Leslie M. Harris, In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626-1863 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 118-119; Leslie M. Alexander, African or American? Black Identity and Political Activism in New York City, 1784-1861 (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2008), 103. [20] Andrew Kahrl, “‘The Slightest Semblance of Unruliness’: Steamboat Excursions, Pleasure Resorts, and the Emergence of Segregation Culture on the Potomac River,” Journal of American History 94, No. 4 (March 2008), 1109-1110, 1134, 1121, 1123. [21] David R. Roediger, The Wages of Whiteness: Race and the Making of the American Working Class (London: Verso, 1991), 167-180. [22] For accounts of “riots” on Black excursions, see “Colored Picnicker in a Row: Charges of Theft Almost as Numerous as Blows,” New York Times, August 23, 1895, 2; “An Excursion Lands for Police,” New-York Tribune, July 28, 1899, 8; “Riot at a Negro Picnic: Several Stabbed or Shot on a Barge,” New York Times, June 20, 1907, 8; “Fight at a Picnic,” New York Times, August 29, 1884, 5. [23] “Razors Flashing Fast,” New York Times, July 22, 1887, 5. [24] “A Negro Picnic: A Free Fight in which Razors, Beer Mugs and Clubs Play a Promiscuous Part,” The Auburn, July 22, 1887, 1; “Razor and Beer Mugs: Implements of War Used by Colored Excursionists,” Syracuse Weekly Express, July 27, 1887, 6. [25] “Almost a Riot on an Excursion Barge,” New-York Tribune, July 22, 1887, 5. [26] Historian Andrew Kahrl analyzes negative portrayals of Black excursions from Washington, D.C. to a destination that the press called “Razor Beach” in the late nineteenth century. Biased and inaccurate reporting led to increased policing of the waterfront and an unjust targeting of people of African descent. Kahrl, “The Slightest Semblance of Unruliness,” 1121, 1136, 1119, 1122-1126. AuthorMarika Plater is a PhD Candidate in History at Rutgers University who studies environmental inequality in nineteenth century New York City. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today! Editor’s Note: The following text is a verbatim transcription of an article featuring stories by Captain William O. Benson (1911-1986). Beginning in 1971, Benson, a retired tugboat captain, reminisced about his 40 years on the Hudson River in a regular column for the Kingston (NY) Freeman’s Sunday Tempo magazine. Captain Benson's articles were compiled and transcribed by HRMM volunteer Carl Mayer. See more of Captain Benson’s articles here. This article was originally published August 18, 1974. During the 1920's, every Sunday from late May until early September, the steamer “Homer Ramsdell" of the Central Hudson Line offered an excursion from Kingston to New York. Leaving Rondout at 6:30 a.m., she would make landings at Poughkeepsie and Newburgh and arrive in New York at her pier at the foot of Franklin Street at 1 p.m. Returning, she would leave New York at 4:30 p.m. and get back to Kingston at 11 p.m. In those days of long ago, the Sunday excursions on the “Homer Ramsdell” were very popular with residents of the mid-Hudson valley and many Kingston families made this day long sail on the Hudson an annual event. In July of 1924, as a boy of 15, my father took me on one of these excursions. To a boy who thought the greatest thing in the world was a steamboat, the excursion was a memorable experience. I made a note of every steamer we passed and in retrospect it is difficult to believe there were once so many steamboats in operation on the Hudson. After leaving Rondout on that sunny Sunday morning a half a century ago, the first steamer we met was the “Poughkeepsie” of the Central Hudson Line, off Staatsburgh. She was coming up on her way to Kingston, having left New York the night before. Landing at Poughkeepsie, I saw the ferryboat “Gove Winthrop” going into her Poughkeepsie slip and her running mate “Rinckerhoff" [Brinckerhoff?] landing at Highland. After we left Poughkeepsie, we saw very few boats as it was too early in the morning. At Newburgh, the old ferryboat "City of Newburgh” was just coming over from Beacon and as we passed Cornwall we overtook the "Perseverance” of the Cornell Steamboat Company going down with the down tow of about forty loaded scows and barges. The Cornell tugs “Victoria” and ‘‘Hercules” were helping on the tow. When passing West Point, the ferry “Garrison” was going over the river to her namesake landing. Down off Grassy Point, the graceful “Hendrick Hudson” of the Day Line went by on her way to Albany and looked as if she were almost loaded to her passenger capacity of 5,500. Off Croton Point, the brand new “Alexander Hamilton” went past on her way to Kingston Point — and just below Hook Mountain the “DeWitt Clinton” was going up river bound for Poughkeepsie. Not too far behind her was the “Albany,” probably going to Indian Point. In slightly over an hour we had passed four Day Liners. Then came the Bear Mountain steamer “Clermont.” By that time we were off Tarrytown. Looking down the river on that clear day, one could see all the way down to New York harbor and could see everywhere all kinds of passenger steamboats and yachts coming up the river. I was eagerly peering ahead to see if I could find my favorite, the “Benjamin B. Odell.” Sure enough, there she was coming up river with a big bone in her teeth, flags flying and black smoke pouring out of her big black smokestack. The "Odell" was overtaking the “Rensselaer” of the Albany Night Line — and had just passed the propellor “Ossining” and the sidewheeler ‘‘Sirius" of the Iron Steamboat Company. As she sped by the “Ramsdell", she blew one long blast salute on her whistle. The white steam from her whistle ascending skyward and the big red house flag of the Central Hudson Line with the white letters “C.H.,” briskly flapping in the breeze from the flag staff in back of her pilot house, made a very impressive scene. After we had passed this cluster of steamboats, along came the “Benjamin Franklin” of the Yonkers Line, closely followed by the Day Liner “Robert Fulton" on her way to Newburgh. We then passed the ‘‘Mandalay" headed up river. With her ferry boat-like bow, she was a nice looking steamer. Below Hastings, a tow in charge of the Cornell tugboats “Geo. W. Washburn” and “Senator Rice" was on its way up river. The “Washburn” blew a long salute to the "Ramsdell." Down off Yonkers, the speedy “Monmouth” of the Jersey Central Railroad and the Central Hudson steamer “Newburgh” were coming up, loaded with passengers for a day's outing up the river. When we landed at 129th Street, I couldn't help but wonder how many people had boarded boats at that pier that morning. It must have been several thousand. On the south side of the pier lay the "Cetus" of the Iron Steamboat Company taking on passengers for Coney Island. Going down through the harbor I saw the "Leviathan” of the U.S. Lines, then called the largest liner in the world, lying at her pier. With her three big red, white and blue smokestacks, it was the first time I had ever seen her. Christopher Street, the ‘‘Robert A. Snyder" of the Saugerties Evening Line was lying on the south side. Going up river was the little sidewheeler ‘‘Sea Bird" with her large hog frame and walking beam. The ‘‘Sandy Hook" was just leaving her pier at Houston Street on her way to Atlantic Highlands and the “Mary Patten" was on her way to Gansevoort Street, coming back from Long Branch. By that time it was nearly 1 p.m. and we were landing at the Franklin Street pier. We left New York on our return trip promptly at 4:30 p.m. For the next two and a half hours we passed a steady parade of steamboats, only this time they were all returning to New York. We passed again all of the steamers we had in the morning except the "Hendrick Hudson" which had gone on to Albany. In her stead, we passed the big “Washington Irving" which that day was the down Day Liner from Albany. The down Cornell tow in charge of the "Perserverance" had gotten all the way down to Hook Mountain. As we passed very close I remember how loud her whistle sounded when she blew a passing salute. When we were at Iona Island, I could see the "Onteora,” another favorite of mine, just pulling away from Bear Mountain. That was the first I had seen her in two years as she had gone up river after we had landed at New York. My older brother, Algot, had been the mate of the “Onteora" and in March of the year before he died of pneumonia. When my father saw the “Onteora" ahead, I remember he got up and without saying a word walked to the other side of the "Ramsdell." I suppose he could not bear to see her got [go?] by knowing my brother was no longer aboard. As the "Onteora" went by she was just straightening out on her course down river with a heavy port list after completing her turn around. We passed so close I could make out Ben Hoff, her captain, at the wheel in the pilot house. We again passed the “Geo. W. Washburn” and the "Senator Rice" with the up Cornell tow off Cons Hook. After we left Newburgh we passed the steamer ‘‘Ida" of the Saugerties Evening Line on her way to New York and, off Danskammer Point, the freighter "Storm King" of the Catskill Evening Line also bound south. After that, as far as I know, we didn’t pass anything. I remember dozing off in an easy chair on the saloon deck and getting off at Rondout about 11 p.m, and going home to bed. For a boy, it had been a day to remember. AuthorCaptain William Odell Benson was a life-long resident of Sleightsburgh, N.Y., where he was born on March 17, 1911, the son of the late Albert and Ida Olson Benson. He served as captain of Callanan Company tugs including Peter Callanan, and Callanan No. 1 and was an early member of the Hudson River Maritime Museum. He retained, and shared, lifelong memories of incidents and anecdotes along the Hudson River. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Vienna Carroll performs this version of Shallow Brown, a Caribbean sea shanty. Ms. Carroll has written a musical play about pre-Civil War Black sailors. The sea shanty Shallow Brown is a song by and about a Jamaican slave sold off to a Yankee ship owner, who is jumping ship to find a better life. Shallow Brown shares the under-told story of the critical impact of Black sailors on the antebellum maritime economy and on the lives of the Black community and it highlights their activities in the Underground Railroad. Vienna presented an excerpt (and research journey) at the 39th Mystic Sea Music Festival Symposium in 2018 and debuted a full reading at the Langston Hughes House in Harlem in the Fall. She kicked off the first Langston Hughes playwright showcase to a packed house on May 3, 2019. Vienna was scheduled to perform at the Cold Springs Whaling Museum and at the 41st Mystic Sea Music Festival this year in 2020. http://shallowbrown.com/ Vienna Carroll is a singer, playwright, actor, historian and herbalist. Vienna learned music from the Black Ladies of her youth, including her fearsome great grandmother who played guitar to country singer Minnie Pearl on Saturday night radio but only proper Pentecostal chords in church on Sunday. Vienna also sang in the choir at her family’s AME church, and attended her godmother’s Baptist church. At her Alabama grandmother’s 125 acre working farm, she listened to gospel and country on the radio and joined in the Sunday church services an hour’s drive away down a dusty road, where singing was often accompanied only by the hand clapping and shouting of its fervent members. She later formalized her study of early African American music and culture at Yale University, where she received a BA in African American Studies. http://viennacarroll.com/ SHALLOW BROWN - LYRICS Say I’m going away to leave you, Oh, Shallow Brown Yes, I’m going away to leave you, Oh, Shallow Brown Say I’m signed on to a whaler, Oh, Shallow Brown I’m signed on for a sailor, Oh, Shallow Brown Well I've got my clothes in order, Oh, Shallow Brown ‘Cause my packet leaves tomorrow, Oh, Shallow Brown Say I love you Juliana, Oh, Shallow Brown Yes I love you Juliana, Oh, Shallow Brown Say my master’s gonna sell me, Oh, Shallow Brown Says he’ll sell me to a Yankee, Oh, Shallow Brown Says he’ll sell me for a dollar, Oh, Shallow Brown A big, fat Spanish dollar, Oh, Shallow Brown Gonna climb the Chili mountain, Oh, Shallow Brown Gonna find the silver fountain, Oh, Shallow Brown Say I’m bound away for to leave you, Oh, Shallow Brown But I never will deceive you, Oh, Shallow Brown Fare you well, my Juliana, Oh, Shallow Brown Fare you well, my Juliana, Oh, Shallow Brown Thanks to HRMM volunteer Mark Heller for sharing his knowledge of Hudson River music history for this series. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's Note: This detailed account of the fire on the Citizens' Line steamer City of Troy at Dobbs Ferry is from the April 6, 1907 New York Times. The tone of the article reflects the time period in which it was written. CITY OF TROY BURNS IN HUDSON The Old River Steamer Lands Her 65 Passengers Just in Time. A FIRE OFF DOBBS FERRY Captain the Last to Leave After Bringing Her to Edwin Gould's Pier. BOAT A WRECK IN AN HOUR Fire Started in Mid-River at 9 o'clock - No Panic - Some Passengers , Helped Fight the Flames. With her hold a mass of crackling flames, the big steamer City of Troy of the Citizens' Line, a wooden side-wheeler, 280 feet long, on which were 65 passengers, plowed through the Hudson at full speed last night, her Captain endeavoring to find a pier to which he might tie long enough to land the passengers and crew. The City of Troy was on the Jersey side of the river off Yonkers, going up the river, when the fire was discovered, and it was an hour later before she was finally tied up at the private pier of Edwin Gould at Dobbs Ferry. There every passenger was safely landed. Mate W. S. Eagle was the only one overcome by smoke. He was taken ashore and soon recovered. The vessel, an hour later, was a blackened mass burned to the water's edge. Some of the passengers who had retired early, were already asleep when shortly after 8 o'clock tiny puffs of smoke creeping up through hatches and companionways were noticed by other passengers and deckhands. The fire alarm signal was rung through the boat and the crew rushed to their places, while terrified passengers rushed to the decks begging to be told what had happened. Many had been awakened from sleep by the alarm, and these, rushing on deck, added to the excitement. In the meantime the flames had been found in the hold amidships. It is thought detective insulation on the electric wiring in the pantry started the fire. It gained rapid headway, eating its way fore and aft and licking at the deck above. Several streams of water were quickly turned into the hold and a desperate fight was made to check the flames. Many of the more cool-headed of the passengers joined with the crew in handling hose and carrying water. Across the River on Fire. Despite their efforts[,] the flames continued to gain headway. When it was seen that there was no longer hope of saving the boat[,] Capt Charles H. Bruder turned his vessel's head off the shore and rung for full speed ahead. Straight across the river the boat ploughed, and at the Dobbs Ferry pier an effort was made to tie up. For some reason the boat could not be made fast, and, despairingly, Capt. Bruder turned toward the pier of the Manila Anchor Brewery. The terror of the passengers was redoubled when it was found that here also the boat would be unable to land. By this time, too, the flames had gained dangerous headway and the passengers crowded on to the upper decks. When the vessel approached Dobbs Ferry there was to those ashore no sign of fire aboard except a cloud of smoke trailing off to the stern, as she ran shoreward, and her whistles for help did not seem justified to those who saw her approaching. There was no panic aboard as the boat neared land. All hands were ready to leave as quickly and quietly as might be. Planks were run out to the pier, and everybody got off safely, though it was said none of the baggage was saved. There being only a few passengers, they got off in two minutes. Some time after she landed the vessel drifted away from the pier somewhat. She was then ablaze from stem to stern. Capt. Bruder was the last man off and he left in a rowboat. When the steamboat was laid alongside the pier the crew had knocked out the forerail and had a gangplank ready to run out. It took but a couple of minutes to get the passengers ashore and on to the tracks of the Central Railroad. The fire broke out all over the vessel, flames breaking forth in a dozen places just as the last of the passengers got ashore. Running toward the east side of the river, the steamboat had been running with the wind, so that there did not seem to be much draught for the fire, but once she stopped and the wind began to whistle through her the flames seemed to leap out in a dozen places. The fire swept through the boat within a very few minutes. All effort had to be turned toward saving the brewery and the pier as well as the cottage on the pier. The latter was saved, as was the brewery, but a portion of the pier will have to be rebuilt, even to the pilings as the fire extended to it. Then Capt Bruder ran his boat toward Mr. Gould's dock. Here at last he was able to make fast, and with the flames crackling almost at their heels[,] the passengers were tossed and tumbled over the gang planks to the pier. The Dobbs Ferry Fire Department had turned out as the blazing City of Troy was seen approaching the town, and the men set to work to save the steamer. Their work was hopeless, however, and the flames were already eating into the upper works of the steamer when the word flashed through the crowd that a woman passenger was still asleep in her berth. Alfred Smith and Robert Wilson of the Fire Department immediately darted down into the burning cabin. Choking with the dense smoke they fought their way from stateroom to stateroom until they came to one which was locked. Sleeping Passenger Saved. Putting their shoulders to the door they smashed it in. In the berth they found a woman, whom neither smoke nor noise had awakened. She had not been overcome by smoke, however, and grabbing her in their arms, Smith and Wilson rushed with her to the deck. From here she was got safely ashore. In the meantime the flames had been communicated to the pier, and this, too, soon blazing fiercely, driving the firemen, back foot by foot, until at last they were compelled to abandon all hopes of saving the vessel. On board of her were thirteen horses, besides a valuable cargo of freight. All the horses and the freight were lost. Before the firemen were driven from the pier an effort was made to reach the horses. Several men dropped into the burning hold, but it was quickly found that the horses could not be reached. The passengers hurried to the railroad station after leaving the boat, and many of them returned to this city on the 11:30 o'clock train, while others left for Troy shortly after midnight. STORIES OF PASSENGERS. All Praise Bravery of Capt. Bruder, Who Was Last to Leave. Seven passengers and about twenty-five members of the City of Troy's crew arrived at the Grand Central Station on the 12:53 train from Yonkers this morning. The passengers looked very little the worse for their experience, but it was different with most of the crew. They were asleep in their bunks when the fire was discovered, and as the quarters were close to where the fire started they had no time to get together their belongings. Several of the negro stewards when they got to New York had on only an undershirt, overalls, shoes, and a blanket. They were bareheaded, and were still wondering what had happened when sadly they walked down the platform of the Grand Central. On only one point did those who got here this morning agree, and that was the bravery of Capt. Bruder, the skipper of the City of Troy. The skipper, all said, was the bravest man on the boat, and it was not until the last person had been safely landed that he made his way through the smoke to the gangway that led to Edwin Gould's dock at Dobbs Ferry. "I was in the engine room watching the machinery;" said Carl Carlson of 5 Water Street, this city, "when the fire was discovered. I immediately ran up on deck and made my way to the bridge. where I informed Capt. Bruder what was the matter. I never saw a cooler man than that Hudson River skipper. He did not lose his head for a single second. He called his officers to him and then ordered every man to the place assigned to him in the fire drill. Captain Reassures Passengers. Then he made his way to the saloon where the passengers were and begged them to keep cool and trust to him to get them to land. He said that we were in danger, but that the greatest danger of all was a panic. When we got ashore he told us to meet him at the police station and he would furnish us transportation to wherever we wished to go. Then the skipper rushed back to the bridge and guided the boat to the pier at Dobbs Ferry. So far as I know no one was lost, although I did hear that two men had jumped overboard but were rescued. "The passengers had just finished dinner and were making themselves known to one another in the saloon," said R. H. Keller of Troy, "when the skipper came into the saloon and informed us in a cool business-like way that bad luck had come our way, and that the boat was on fire. Several of the women appeared to be on the verge of going into hysterics, but the skipper had foreseen all that and assured them that the greatest danger of all lay in their losing their heads. Then he told us what to do and where to go, and hurried back to his place on the bridge. "It was as cool a piece of work as I have ever seen under such serious conditions. 'Meet me at the police station and I'll send you home,' the skipper said as he hurried out of the saloon." As far as I was able to ascertain," said Frank Fletcher, one of the engineers of the City of Troy, "the fire started in the pantry, which is located on the main deck about amidships. I have not yet learned the cause, but imagine that defective insulation must have started it. The moment the skipper realized what the matter was[,] he headed straight for Dobbs Ferry. There was not any panic, and we did not lose a soul, either among the passengers or the crew." Four Streams Didn't Check Flames. "When the fire alarm was sounded Capt Bruder hustled every man to the place assigned to him in the fire drill, and soon we had four streams playing on the fire. Despite our efforts the flames gained rapidly on us, and in a few minutes after we bumped up against the dock at Dobbs Ferry the boat was a mass of flames from stem to stern. "We were going at full speed when the fire started, that is, about 14 knots an hour. The most pitiful incident of the fire was the loss of seven [or 13?] fine horses that we had on board. We all wanted to save the poor beasts, but it was impossible to do so. I do not know to whom the animals belonged." Michael Murray and Thomas O'Hara were two of the crew that arrived here this morning. They did the talking for their fellows and all agreed that they were mighty lucky to get back to New York alive. Most of these men were asleep when the fire drill was sounded. They did not stop to pick up any of their personal belongings, but hustled on deck to help try put out the fire. O'Hara said that Capt. Bruder had to be taken off the ship in a lifeboat, as the vessel was ablaze from stem to stern on the landing side when the skipper deserted the boat, after the last of the passengers were taken off. Some of the others said that O'Hara was mistaken in this and that the skipper had left the boat via the gangplank, which he reached by a perilous groping through the smoke that enveloped the ship. The negro cooks and stewards were the great sufferers and saved almost nothing at all. Several of them had very few clothes on last night and were trying to keep themselves warm with blankets that had been given them by kindhearted people in Dobbs Ferry. One of the crew said that one of the officers found a crowd of fifteen excited Italians preparing to jump overboard. He remained among them until the boat landed, after issuing a standing threat to brain the first man that moved, with a belaying-pin. The Italian re[m]ained quiet. The City of Troy was a wooden side-wheel steamboat, 280.6 feet long and 38 feet in breadth, drawing ten feet of water. She was built in Brooklyn in 1876 for inland passenger service, and had continued in the Hudson River service for the Citizens' Steamboat Company since. She cost $250,000 originally. Her gross tonnage was 1,527, and net tonnage 1,280. The steamboat had a crew of forty-eight men and 200 staterooms. Some thirteen years ago, when the present management of the Citizens Line assumed control, the boat was remodeled at a cost of $150,000. On each deck she was provided with fire cocks and hose. The officers and crew have always been considered most efficient, and were well versed in the fire drill. AuthorThank you to HRMM volunteer George Thompson, retired New York University reference librarian, for sharing these glimpses into early life in the Hudson Valley. Thank you to HRMM volunteer Carl Mayer for transcribing these articles. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

In 1825, the Erie Canal was completed with the hopes of improving and expanding economic opportunity between the areas surrounding Lake Erie and the Hudson River. Having proved to be a great success, the state of New York seized many opportunities to further develop the waterway. As such, they undertook multiple enlargement projects. The final project integrated the Erie Canal into the New York State Barge Canal system. Finished in 1918, the system also includes the Cayuga-Seneca, Champlain, and Oswego canals. All of which were originally built within a few years of the Erie Canal’s completion. The project not only enlarged the dimensions of all four canals but also altered their original routes. The Barge Canal era is represented in a shipwreck located in Kingston’s Rondout Creek, the Frank A. Lowery. Constructed in Brooklyn, New York the same year that the Barge Canal was completed, the Lowery was likely built to take advantage of the opportunities provided by the new-and-improved waterway. The barge Frank A. Lowery, then registered as OCCO 101, began operation under the ownership of the Ore Carrying Corporation. According to the 1921 publication of the Annual Report of the Superintendent of Public Works for New York State, “the Ore Carrying Corporation … engaged in the transportation of iron ore from Port Henry on Lake Champlain, to Elizabethport, N.J.”. The report also notes that in terms of the amount of ore shipped per season, the company was substantially more productive in 1920 than it was in 1919. In fact, the company shipped over three times the amount of ore in 1920 than it did the previous season. Having joined the company’s fleet in 1918, the OCCO 101 likely assisted the company in achieving this feat. Ownership was transferred to the L. & L. Canal Line in 1926 and the vessel was renamed L & L. 101. As shown in the 1930 publication of Inland-waterway Freight Transportation Lines in the United States, the L. & L. Canal Line shipped steel and pig iron on the New York State Barge Canal. Based in New York City, the line had six wooden barges that could be found traveling the waters to and from Buffalo, New York. Finally, Frank A. Lowery purchased the vessel and renamed it after himself in 1929. Though much about Lowery remains unknown, the Merchant Vessels of the United States publications for the years 1930 and 1936 list Lowery as living in Creek Rocks, New York. However, in the publication for the year 1951, he is listed as living in Athens, New York. The later record also notes that he owned six vessels, including the Frank A. Lowery. While it is unclear who initiated the renovations, the vessel was refit with an engine in 1929. This renovation distinguished the Lowery from other canal boats and allowed for its classification as a Hoodledasher, or a powered canal boat. As such, it could move itself through the water with two hundred and forty horsepower and could be used to both tow and carry cargo. Following these renovations, the Lowery measured 104 feet in length, 21 feet in beam, and had a tonnage of 195 net tons. Surely, such a vessel was viewed to be a more efficient option. The Frank A. Lowery was put to use as the leading vessel of the Lowery flotilla, which also included the six barges it towed. A 1955 New York District Court case, further discussed below, provides a glimpse into the history of the vessel under the ownership of Frank Lowery. This includes what was transported in the vessel’s cargo hold as well as the routes it covered: “The Lowery flotilla . . . sailed the waters of the Hudson River and Barge Canal for a considerable number of years. It was old in the service of carrying cargo, well known to the trade and canal and river people, and on many… occasions it carried scrap iron west from New York City to Buffalo, and grain east from the terminal at Buffalo to the City of Albany.” In 1953, the Frank A. Lowery was involved in an incident that resulted in a district court case. According to the case report, the Lowery flotilla was on its way to the Port of Albany when a steel barge collided with the last vessel in the flotilla tow, the Marion O’Neill. The steel barge was being pushed by the Ellen S. Bouchard of the Bouchard Transportation Company. Having caused a chain reaction, the Marion O’Neill then collided with yet another barge in the tow, the Mae Lowery, and both vessels subsequently sank. The Mae Lowery’s misfortune continued when it was struck by the unsuspecting Clayton P. Kehoe of the Kehoe Brothers Transportation Company nearly two hours after the initial collision. The day’s events resulted in one presumably fatal casualty, the captain of the Marion O’Neill. The Lowery was abandoned east of Rondout Creek’s Sunflower Dock following an accident in 1953, perhaps the one mentioned here, and her valuable effects were salvaged five years later. The vessel’s tell-tale hanging and lodging knees, half-round bow, and parallel sides allowed for the easy identification of the wreck for many years. However, the structure continues to deteriorate with the erosive nature of weather and ice. Soon, only her keel will remain. AuthorLauryn Czyzewski is a Hudson River Maritime Museum volunteer. Her interests include twentieth and twenty-first century maritime history and shipwrecks. She graduated from SUNY Potsdam with a bachelor’s degree in Archaeological Studies. Lauryn would like to thank the editors of this article, Sarah Wassberg Johnson and Mark Peckham. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Recorded in the summer of 1976 in Woodstock, NY Fifty Sail on Newburgh Bay: Hudson Valley Songs Old & New was released in October of that year. Designed to be a booster for the replica sloop Clearwater, as well as to tap into the national interest in history thanks to the bicentennial, the album includes a mixture of traditional songs and new songs. This album is a recording to songs relating to the Hudson River, which played a major role in the commercial life and early history of New York State, including the Revolutionary War. Folk singer Ed Renehan (born 1956), who was a member of the board of the Clearwater, sings and plays guitar along with Pete Seeger. William Gekle, who wrote the lyrics for five of the songs, also wrote the liner notes, which detail the context of each song and provide the lyrics. This booklet designed and the commentary written by William Gekle who also wrote the lyrics for: Fifty Sail, Moon in the Pear Tree, The Phoenix and the Rose, Old Ben and Sally B., and The Burning of Kingston. The men who sailed the sloops on the Hudson River, a hundred years or more ago, came from the farms and villages along its shores. Even long after they became experienced skippers, they spoke and thought more like farmers than sailors. They knew, or came to know, that the moon affected the tides. They knew that when the moon was in the Apogee, the tides were apt to run low and slow, and that when the moon was in the Perigee, the tides were likely to run higher and faster. Being farmers and countrymen at heart, they translated these terms into something with which they were familiar. And so they said that when the moon was in Apogee – it was in the apple tree. And when the moon was in Perigee, it was in the pear tree. https://folkways-media.si.edu/liner_notes/folkways/FW05257.pdf THE MOON IN THE PEAR TREE - LYRICS Look up, sailor, and you’ll see, The moon hangin’ up in the old pear tree, The old pear tree on the crest of the hill, While the moon draws the tide and the rivers fill. What better can a sailor hope to see Than the moon hangin’ up in the old pear tree! Look up, sailor, and you’ll see The moon hangin’ up in the apple tree, The apple tree grows in the yard out back While the moon holds the tide and the waters slack, So a sailor’s not so very glad to see The moon hangin’ up in the apple tree. Look up, sailor, and don’t be sad, The wind and the tide are bringin’ up shad, The shad and smelt and the sturgeon too, Comin’ up the River like they used to do. So look up, sailor, and pray to see The moon hangin’ up in the old pear tree. Look ahead, sailor, and you’ll see, Times a-comin’ back like they used to be, When the water’s clear and way up high Once more you see the stars in a clear blue sky. What better can a sailor hope to see Than the moon hangin’ up in the old pear tree. Thanks to HRMM volunteer Mark Heller for sharing his knowledge of Hudson River music history for this series. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's Note: The following text is a verbatim transcription of an article written by George W. Murdock, for the Kingston (NY) Daily Freeman newspaper in the 1930s. Murdock, a veteran marine engineer, wrote a regular column. Articles transcribed by HRMM volunteer Adam Kaplan. No. 174- Berkshire The tale of the steamboat “Berkshire” is yet uncompleted as the vessel is still in existence, but for the past two seasons she has not been in service, and it is doubtful as to whether she will ever again ply the waters of the Hudson river. The steel hull of the “Berkshire” was built by the New York Shipbuilding Company of Camden, New Jersey, in 1907, and her engine was the product of W. & A. Fletcher Company of Hoboken, New Jersey. The dimensions of the vessel are listed as follows: Length of keel, 422 feet; overall length, 440 feet; breadth of beam, 50 feet six inches; over guards 90 feet; depth of hold 12 feet nine inches. The gross tonnage of the “Berkshire” is listed at 4300, with net tonnage at 2918. Her engine is the vertical beam type with a diameter cylinder measuring 84 inches with a 12 foot stroke. The launching of the steamboat known to the Hudson river as the “Berkshire” occurred in September, 1907, with the name “Princeton” appearing instead of “Berkshire.” The vessel was originally built for service between New York and Albany under the banner of the People’s Line, but for some reason was not completed after she was launched. For almost six years the uncompleted steamboat lay off Turkey Point on the Hudson river, and finally in 1913 construction was completed and the “Berkshire” began her career on the Hudson river. The People’s Line was always known to travelers of the river for its up-to-the-minute steamboats. Their vessels were the last word in steamboat construction with comfortable accommodations and luxurious furnishings- and the “Berkshire” was no exception. If there was anything lacking in the make-up of the “Berkshire” that would add to the safety and comfort of the passengers or the beauty and stability of the craft, it had not yet been invented or discovered. In 1913 the “Berkshire” entered service, running on the Albany route in line with the “C.W. Morse,” and taking the place of the steamboat “Adirondack.” The latter vessel was laid up as a spare boat. With accommodations for 2,000 passengers and an average speed of 18 miles per hour under ordinary conditions, which could be increased to 20 miles per hour if necessary, the “Berkshire” son proved to be a popular vessel with river travelers. She boasted passenger elevators, a palm room, café and smoking room on the upper deck, richly furnished salons, and other modern features of river travel. The “Berkshire” and the “Fort Orange,” formerly the “C.W. Morse,” were in regular service as night boats running to Albany in 1927. The “Berkshire” continued on the Hudson river until 1937- running in line with the “Trojan” during that season; and then she was laid up at Athens, where she has remained without turning a wheel for the past two seasons. Whether or not the “Berkshire” will again appear in regular service is unknown, but with the decline in river travel, followers of the steamboats are inclined to believe that the next trip of the “Berkshire” will be her last- to the scrap heap. In 1941 the U.S. Government took an option on the “Berkshire.” She was towed to Hoboken, New Jersey on January 31, 1941. On June 25, 1941, “Berkshire” was towed to Bermuda to be used there as quarters. After the war she was broken up in Philadelphia. AuthorGeorge W. Murdock, (b. 1853-d. 1940) was a veteran marine engineer who served on the steamboats "Utica", "Sunnyside", "City of Troy", and "Mary Powell". He also helped dismantle engines in scrapped steamboats in the winter months and later in his career worked as an engineer at the brickyards in Port Ewen. In 1883 he moved to Brooklyn, NY and operated several private yachts. He ended his career working in power houses in the outer boroughs of New York City. His mother Catherine Murdock was the keeper of the Rondout Lighthouse for 50 years. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor’s Note: The following text is a verbatim transcription of an article featuring stories by Captain William O. Benson (1911-1986). Beginning in 1971, Benson, a retired tugboat captain, reminisced about his 40 years on the Hudson River in a regular column for the Kingston (NY) Freeman’s Sunday Tempo magazine. Captain Benson's articles were compiled and transcribed by HRMM volunteer Carl Mayer. See more of Captain Benson’s articles here. This article was originally published July 23, 1972. When the steamboat ‘‘Clermont" was running on the Catskill Evening Line around 1914 to Catskill, Hudson and Coxsackie, the steamer had a pilot the quartermaster and lookout didn’t particularly care for. The younger men in the crew could never seem to please him in any way. In those days, the quartermaster generally was a young fellow starting out on his steamboat career. It was his job to keep the pilot house neat and clean, see that the brass was polished, and to assist the pilots as they directed. The quartermaster would frequently steer the steamer under the pilot's direction and, in this way, he would “learn the river.” It was also the quartermaster’s duty at about 2 or 3 a.m. to go down to the galley and make a couple of sandwiches and coffee to take up to the pilot house for the pilot on watch. No More Beer On the night of this particular incident, the pilot had told the captain he had seen the quartermaster that afternoon up on Reed Street in Coxsackie talking to some girls and having a glass of beer instead of sleeping on the boat to be rested for the night trip to New York. To keep peace with his pilot, the captain admonished the quartermaster and told him not to do it again. Early the next morning as the “Clermont” was paddling her way down the Hudson to New York, the quartermaster went down to the galley to make the usual sandwiches and coffee for the pilot house. Still smarting from the rebuke he had received as the result of the pilot's remarks about him to the captain, the quartermaster took a piece of toilet paper and placed it between the slices of ham in the sandwiches he was making. Then he slapped some mustard on the ham and took the sandwiches and coffee up to the pilot house. At that hour of the morning the pilot house, of course, was completely dark. The pilot took the two sandwiches and ate them with great relish, apparently being more hungry than usual. He never even noticed the toilet paper between the slices of ham. Orders Another After finishing the sandwiches, the pilot said, “They were real good. Go down to the galley and make another.” This time, however, the quartermaster apparently lost his nerve and made the new sandwich in the more conventional way. After the pilot ate the new sandwich, he turned to the quartermaster and said, “That one wasn't as good as the first two. I guess you must have used a different ham!" And on the “Clermont” steamed on her way to New York, Reed Street, Coxsackie left far behind, with only the soft breezes of a summer's night to disturb the serenity of the dark pilot house. Changing Economy ... Actually, the peaceful scene in the “Clermont’s" pilot house was soon to be disturbed by other factors. Changing economic conditions, due primarily to the growing use of the automobile and motor trucks and the changing vacation habits of former patrons, caused the Catskill Evening Line to go into receivership in January 1918. Passenger carrying operations were abandoned altogether and during the season of 1918 the “Clermont," and her running mate “Onteora," ran under charter on an opposition night line to Troy. The “Clermont” and ‘‘Onteora” lay idle during 1919 and in September of that year were purchased by the Palisades Interstate Park Commission. They were converted into excursion steamboats to run from New York to Bear Mountain and entered this service in 1920. The “Clermont" was renamed “Bear Mountain" in 1947, ran for the last time during the season of 1948, and in 1950 was broken up. AuthorCaptain William Odell Benson was a life-long resident of Sleightsburgh, N.Y., where he was born on March 17, 1911, the son of the late Albert and Ida Olson Benson. He served as captain of Callanan Company tugs including Peter Callanan, and Callanan No. 1 and was an early member of the Hudson River Maritime Museum. He retained, and shared, lifelong memories of incidents and anecdotes along the Hudson River. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Major Henry Livingston, Jr. (1744-1828) went with his cousin's husband, Major General Richard Montgomery, on the 1775 invasion of Canada. These were short term enlistments, so he became major of the 3rd NY in August and returned home in late December. The diary is shown along with the Hudson River School's images of the terrain. The music was transcribed from Henry Livingston's handwritten music manuscript, one of the largest such books of the period. The Journal of Major Henry Livingston of the Third New York Continental Line, August to December, 1775. [edited] By Gaillard Hunt, Washington, D.C. Compiled and created by Mary Van Deusen. http://www.henrylivingston.com/writing/prose/revdiary.htm Thanks to HRMM volunteer Mark Heller for sharing his knowledge of Hudson River music history for this series. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

|

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 [email protected] Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |