History Blog

|

|

|

|

|

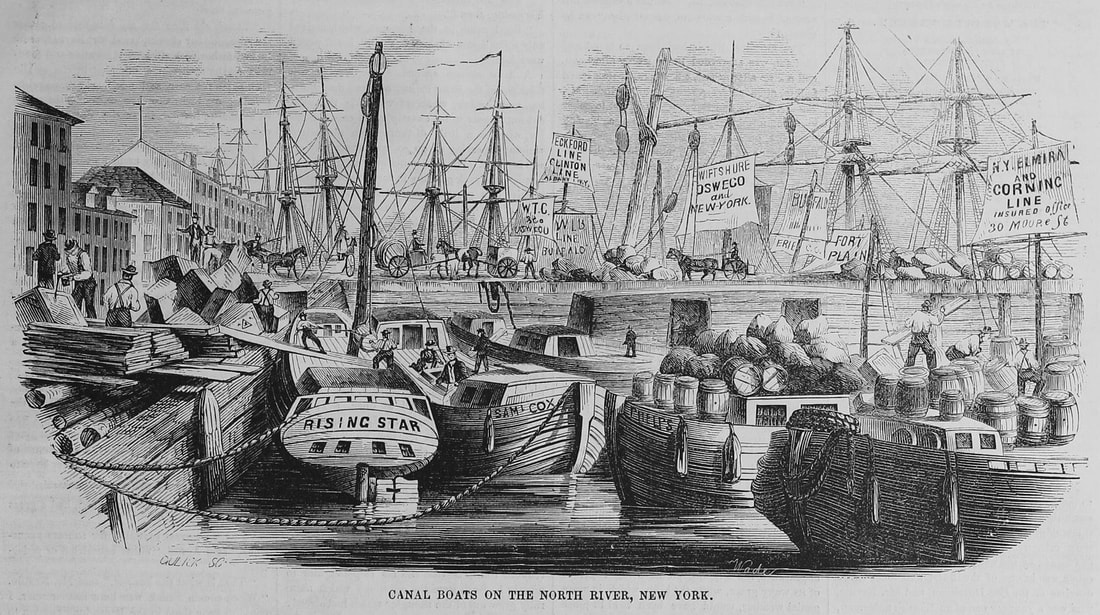

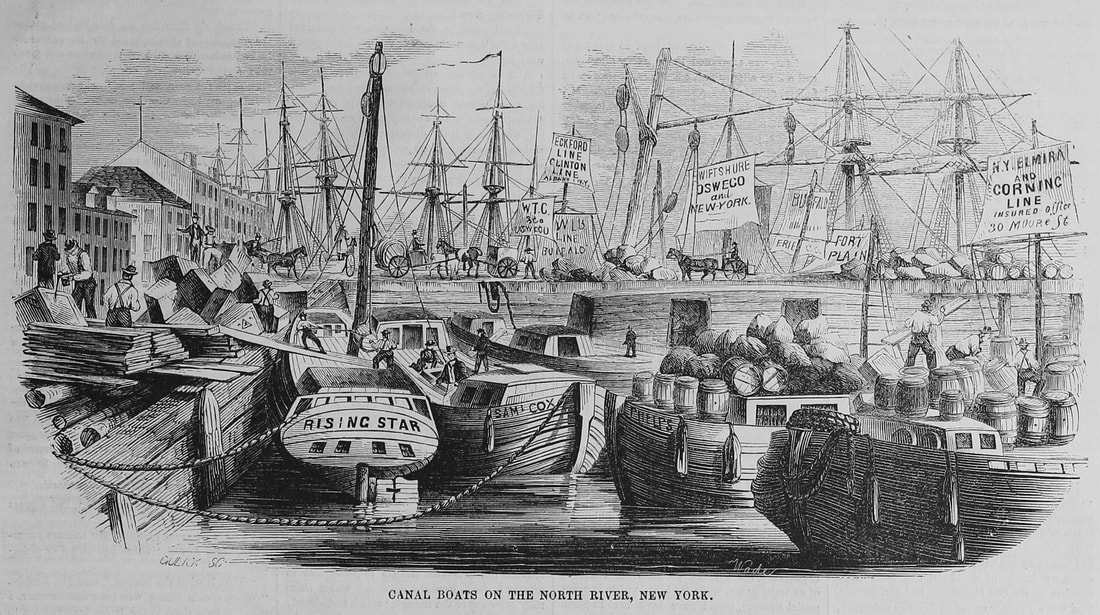

Editor's note: The following excerpts are from the January 3, 1875 issue of the "New York Times". Thank you to Contributing Scholar George A. Thompson for finding and cataloging this article. The language, spelling and grammar of the article reflects the time period when it was written. Loading Her Up. Scenes on the Docks. The Shipping Clerk – The Freight – The Canal-Boat Children. I am seeking information in regard to the late 'longshoremen's strike, and am directed to a certain stevedore. I walk down one of the longest piers on the East River. The wind comes tearing up the river, cold and piercing, and the laboring hands, especially the colored people, who have nothing to do for the nonce, get behind boxes of goods, to keep off the blast, and shiver there. It was damp and foggy a day or so ago, and careful skippers this afternoon have loosened all their light sails, and the canvas flaps and snaps aloft from many a mast-head. I find my stevedore engaged in loading a three-masted schooner, bound for Florida. He imparts to me very little information, and that scarcely of a novel character. "It's busted is the strike," he says. "It was a dreadful stupid business. Men are working now at thirty cents, and glad to get it. It ain't wrong to get all the money you kin for a job, but it's dumb to try putting on the screws at the wrong time. If they had struck in the Spring, when things was being shoved, when the wharves was chock full of sugar and molasses a coming in, and cotton a going out, then there might have been some sense in it. Now the men won't never have a chance of bettering themselves for years. It never was a full-hearted kind of thing at the best. The boys hadn't their souls in it. 'Longshoremen hadn't like factory hands have, any grudge agin their bosses, the stevedore, like bricklayers or masons have on their builders or contractors. Some of the wiser of the hands got to understand that standing off and refusing to load ships was a telling on the trade of the City, and a hurting of the shipping firms along South street. The men was disappointed in course, but they have got over it much more cheerfuller than I thought they would. I never could tell you, Sir, what number of 'longshoremen is natives or aint natives, but I should say nine in ten comes from the old country. I don't want it to happen again, for it cost me a matter of $75, which I aint going to pick up again for many a month." I have gone below in the schooner's hold to have my talk with the stevedore, and now I get on deck again. A young gentleman is acting as receiving clerk, and I watch his movements, and get interested in the cargo of the schooner, which is coming in quite rapidly. The young man, if not surly, is at least uncommunicative. Perhaps it is his nature to be reticent when the thermometer is very low down. I am sure if I was to stay all day on the dock, with that bitter wind blowing, I would snap off the head of anybody who asked me a question which was not pure business. I manager, however, to get along without him. Though the weather is bitter cold, and I am chilled to the marrow, and I notice the young clerk's fingers are so stiff he can hardly sign for his freight, I quaff in my imagination a full beaker of iced soda, for I see discharged before me from numerous drays carboys of vitriol, barrels of soda, casks of bottles, a complicated apparatus for generating carbonic-acid gas – in fact, the whole plant of a soda-water factory. I do not quite as fully appreciate the usefulness of the next load which is dumped on the wharf – eight cases clothes-pins, three boxes wash-boards, one box clothes-wringers. Five crates of stoneware are unloaded, various barrels of mess beef and of coal-oil, and kegs of nails, cases of matches, and barrels of onions. At last there is a real hubbub as some four vans, drawn by lusty horses, drive up laden with brass boiler tubes for some Government steamer under repairs in a Southern navy-yard. The 'longshoremen loading the schooner chaff the drivers of the vans as Uncle Sam's men, and banter them, telling them "to lay hold with a will." The United States employees seem very little desirous of "laying hold with a will," and are superbly haughty and defiantly pompous, and do just as little toward unloading the vans as they possibly can thus standing on their dignity, and assuming a lofty demeanor, the boxes full of heavy brass tubes will not move of their own accord. All of a sudden a dapper little official, fully assuming the dash and elan of the navy, by himself seizes hold of a box with a loading-hook; but having assert himself, and represented his arm of the service, having too scratched his hand slightly with a splinter on one of the boxes, he suddenly subsides and looks on quite composedly while the stevedore and 'longshoreman do all the work. Now I am interested in a wonderful-looking man, in a fur cap, who stalks majestically along the wharf. Certainly he owns, in his own right the half-dozen craft moored alongside of the slip. He has a solemn look, as he lifts one leg over the bulwark of a schooner just in from South America, and gets on board of her. He produces, from a capacious pockets, a canvas bag, with U.S. on it, and draws from it numerous padlocks and a bunch of keys. He is a Custom-house officer. He singles out a padlock, inserts it into a hasp on the end of an iron bar, which secures the after-hatch, snaps it to, gives a long breath which steams in the frosty air, and then proceeds, with solemn mein, to perform the same operation on the forward hatch. Unfortunately, the Government padlock will not fit, and, being a corpulent man, he gets very red in the face as he fumbles and bothers over it. Evidently he does not know what to do. He seems very woebegone and wretched about it, as the cold metal of the iron fastening makes it uncomfortable to handle. Evidently there is some block in the routine, on account of that padlock, furnished by the United States, not adapting itself to the iron fastenings of all hatches. He goes away at last, with a wearied and disconsolate look, evidently agitating in his mind the feasibility of addressing a paper to the Collector of the Port, who is to recommend to Congress the urgency of passing measures enforcing, under due pains and penalties, certain regulations prescribing the exact size of hatch-fastenings on vessels sailing under the United States flag.  "Canal Boats on the North River, New York" by Wade, "Gleason's Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion," December 25, 1852. Note the sail-like signs for various towing lines and destinations, as well as the jumble of lumber and cargo boxes on the pier at left, waiting to be loaded onto the canal boats (or vice versa). I return to my schooner. By this time the wharf is littered with bales of hay, all going to Florida. I wonder whether it is true, as has been asserted, that the hay crop is worth more to the United States than cotton? I think, though, if cotton is king, hay is queen. Now comes an immense case, readily recognized as a piano. I do not sympathize with this instrument. Its destination is somewhere on the St. John's River. Now, evidently the hard mechanical notes of a Steinway or a Chickering must be out of place if resounding through orange groves. A better appreciation of music fitting the locality would have made shipments of mandolins, rechecks, and guitars. Freight drops off now, and comes scattering in with boxes of catsup, canned fruits, and starch. Right on the other side of the dock there is a canal-boat. She has probably brought in her last cargo. And will go over to Brooklyn, where she will stay until navigation opens in the Spring. There is a little curl of smoke coming from the cabin, and presently I see two tiny children – a boy and a girl – look through the minute window of the boat, and they nod their heads and clap their hands in the direction of the shipping clerk. The boy looks lusty and full of health, but the little girl is evidently ailing, for she has her little head bound up in a handkerchief, and she holds her face on one side, as if in pain. The little girl has a pair of scissors, and she cuts in paper a continuous row of gentlemen and ladies, all joining hands in the happiest way, and she sticks them up in the window. This ornamentation, though not lavish, extends quite across the two windows, the cabin is so small. Having a decided fancy, a latent talent, for making cut-paper figures myself, I am quite interested, as is the receiving clerk. I twist up, as well as my very cold fingers will allow, a rooster and a cock-boat out of a piece of paper, and I place them on a post, ballasting my productions with little stones, so that they should not blow away. The children are instantly attracted, and the little boy, a mere baby, stretches out his hands. My attention is called to a dray full of boxes, which are deposited on the wharf for our schooner. Somehow or other the receiving clerk, without my asking him, tells me of his own accord what they contain – camp-stools. I can understand the use of camp-stools in Florida: how the feeble steps of the invalid must be watched, and how, with the first inhalation of the sweet balmy air, bringing life once more to those dear to us, some loving hand must be nigh, to offer promptly rest after fatigue. I return to my post, but alas my rooster and cock-boat have been blown overboard; the wind was too much for them. I kiss my hand to the little girl, who smiles with only one-half of her face; the stiff neck on the other side prevents it. The little boy points to the post and makes signs for more cock-boats. Snow there happens to come along on that wharf an ambulant dealer with a basket containing an immense variety of the most useless articles. He has some of the commonest toys imaginable, selected probably for the meagre purses of those who raise up children on shipboard. There are wooden soldiers, with very round heads but generally irate expressions, and small horses, blood-red, with tow tails and wooden flower-post, with a tuft of blue moss, from which one extraordinary rose blossoms, without a leaf or a thorn on the stem. On that post for ten cents that ambulant toy man put five distinct object of happiness, when the shipping clerk interfered. "It's a swindle, Jacob," he said. That young man was certainly posted in the toy market along the wharves. "You ain't going to sell those things two cents a piece, when they are only a penny? You must be wanting to retire after first of the year. Bring out five more of them things. Three more flower-pots and two more horses. The little girl takes the odd one. What's this doll worth? Ten cents! Give you five. Hand it over. Now clear out. I see you, Sir, watching them children. Poor little mites. No mother, Sir. Father decent kind of fellow; says their ma died this Spring. Has to bring 'em up himself, and is forced to leave them most all day. He is only a deck-hand and will be the boat-keeper during Winter. Been noticing them babies ever since I have been loading the schooner – most a week – and been a wanting to do something for their New-Year's. A case of mixed candies busted yesterday, and they got some. They have been at the window ever since, expecting more; but nothing busted. You can't get in; the cabin is locked, but I can manage it through the window." So my young friend climbed on board, with the toys in his pocket, lifted up the sash, and passed through the toys one by one, the especial rights of proprietorship having been carefully enjoined. Presently all the soldiers and the follower-pots were stuck in the window, and the little girl was hugging the doll. "Loading her up; taking in freight for a vessel of a Winter's day on a wharf isn't fun," said the young gentlemen sententiously. "I shouldn't think it was," I replied. "In fact, there ain't much of anything to see or do on a wharf which is interesting to a stranger." "You are from the country, ain't you?" asked the young man with a smile. "Never seen New-York before? Wish you a happy New Year, anyhow." I did not exactly how there could be any reservation as to wishing me a happy New Year whether I was from the country or not, but supposing that this singularity of expression arose from the general character of the young man, or because he was uncomfortable from the frosty weather, I returned the compliment, inquiring "whether a stiff neck was not very hard on children," and not being a family man, added, "They all get it sometimes, and get over it, don't they ?" "It ain't a stiff neck, it's mumps. Mother sent me a bottle of stuff for the child three days ago, and her father has been rubbing it on, and she's most over it now. When I was a little boy," added the clerk reflectively, "toys cured most everything as was the matter with me." "Just my case," I replied, as we shook hands and I left the wharf. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

0 Comments

Editor's note: The following excerpts are from the "Jamestown (NY) Journal" 1858-1859.. Thank you to Contributing Scholar George A. Thompson for finding, cataloging and transcribing this article. The language, spelling and grammar of the article reflects the time period when it was written. How we smile now at the bungling expedient for rapid traveling that prevailed twenty years ago. By canal boats from Troy through the nine locks at a cent and a half a mile, and board yourself. By packet from Schenectady west, drawn by three horses, on a slow trot, and three days to Buffalo. And up and down yonder hill crept the first railroad, with cars hung on thoroughbraces, and seats for nine inside, and some outside, which were dragged up an inclined place one hundred and eight feet to the half mile, by a stationary engine, and then over the sand plains to the head of State street in Albany. And this was then such a triumph of engineering. What a change! where our fathers crept we fly. The mountains they climb, we tunnel. The hills they toiled up, we level, or divide by a deep cut, thrown arches over ravines at them impassible. . . . Jamestown Journal (Jamestown, N. Y.), July 16, 1858, p. 2 Correspondence of the Journal. VACATION LETTERS, . . . NO. 4. To New York over the Erie Rail Road -- Sleeping Cars -- New York to New Haven . . . . *** On arriving at Dunkirk, we boarded the Night Express, and took our seats in the luxuriously furnished sleeping car, determining to try the virtue of this boasted institution. Lodgings were furnished at 50 cents a man. My little girl who accompanied me was stowed in without extra charge. There were 40 berths in the car, four in each tier, one double birth at the bottom and two above. The upper berths were cane seated frames, the ends of which were fixed into sockets, while the bottoms of the lower were of wood. All were covered with nice hair mattresses, and pillows enclosed by damask curtains, making a very handsome appearance. About nine o'clock the chambermaid who was a buxom, round faced laddie [sic], made up the berths and we turned in. There were about thirty sleepers in the car. *** Think of sleeping in a car, rushing at the rate of thirty miles an hour, along the brink of lofty precipices, leaping black ravines, threading deep cuts, mounting lofty viaducts, and careering through some of the most splendid scenery in the world. ** Jamestown Journal (Jamestown, N. Y.), September 2, 1859, p. 2 [Editor's Note: He remembers the Green Mountains of his childhood] Yet when I visit that place it is all changed. The old forest is gone, the speckled trout have forsaken the pools; the streams are dried up, or flow in straight spade-cut channels, the roaring branch is trained through sluices, or broken over water-wheels. *** Jamestown Journal (Jamestown, N. Y.), July 16, 1858, p. 2 If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

1909 Canal tow upriver from "Canal Boatman: My Life on Upstate Waterways" by Richard Garrity"1/19/2024 Editor's Note: These are excerpts taken from pages 58-64 of "Canal Boatman: My Life on Upstate Waterways" by Richard Garrity, published by Syracuse University Press, 1977. "Toward evening a harbor tug towed us up the North River, where we were placed in the Cornell tow being made up opposite 52nd street. The tow was tied to what was called the 'stake boat,' anchored in the middle of the river. The anchored boats would swing around with the tide when it ran in or out. Tie-up lines stayed tight as the anchored boats rose and fell with the tide. The boatmen now had to stay aboard their boats until the two reached its destination. Early the next morning we started for Albany. Soon after we were underway we were passing by Riverside Park, where the well-known landmark, Grant's Tomb could be seen close to the shoreline. Next we passed Spuyten Duyvil Creek, which separates the northern end of Manhattan Island from the mainland. The creek was named 'Spitting Devil' by the early Dutch settlers because of the violent cross-currents and eddies which occurred when the tide was running in or out. Twelve miles or so from New York we came to the beginning of the Palisades, a series of rocky cliffs that extend for miles along the New Jersey shore on the west side of the river. Resembling tall columns or pillars, they are from 350 to 500 feet in height, an imposing and majestic sight to view while moving slowly up the Hudson. The Palisades ended in Rockland County, New York, but on the way we had passed Yonkers, Dobbs Ferry, Tarrytown, and the village of Rockland Lake. One of my earliest recollections of the Hudson River was the time we were put in a Hudson tow and dropped off at Rockland Lake, soon after we had unloaded lumber in Brooklyn. The village is on the west shore of the Hudson about twenty-eight miles from New York. Here we loaded crushed stone for an upstate road-building job. The crushed stone from Rockland Lake was highly valued as a base for good roads. Canal boats carried the stone to many places in the state. Some of it went as far west as Seneca Falls, where it was used for a road-building job between that won and Waterloo., While waiting to load on that earlier trip, I remember a warm evening we all went swimming in the Hudson. The bathing party included our family and a young woman named Clara, a guest and friend of my mother from Tonawanda, who had come along for a pleasure trip. While we were all swimming, it was mentioned how much easier it was to swim and float in salt water. What I remember best was my Dad paddling around with me on his back, as i had not yet learned to swim. When slowly passing up the Hudson in a river tow it was always a pleasing sight to see the large passenger boats that ran between New York and Albany. When they met or passed tows on the river, you could see the spray and foam rising from the side wheels and hear the noise of the paddles as they slapped the water. On the top deck, one could see the walking beam that connected the boat's engines to the paddle wheels, constantly rising up and down, driving the boat forward and creating a huge swell as it neared the tow. These swells always brought forth a few cuss words from the canal and bargemen, because they made the tow heave and surge, sometimes breaking the towlines. When passing a tow, the passenger boats always slowed down some, but never enough to suit the men in charge of the tow. When we reached Kingston, we were no longer in salt water. The natural current in the Hudson River kept the tide from carrying the salt water any farther upstream. From Kingston almost to Albany, the shores of the river were dotted with wooden ice houses, which were filled each winter when the river had frozen over. During the season of navigation the ice was shipped by special barges to New York City. Electric refrigeration was a long way off when these ice houses were built. The ice barges were picked up and dropped off at the various ice houses by the same large tows that handled the canal boats on the river. The ice houses and barges belonged to the Knickerbocker Ice. Co. The deck house and cabin of the barges were painted bright yellow, and the hull of the lower part was light gray color. Each barge had a windmill mounted on top of the cabin, which powered a bilge pump that kept the barge free of melting ice and bilge water. Not many barge captains would stay on a boat where they had to strain their backs, working a hand pump every spare moment. The company's name and the windmill mounted on a ten-foot-high tower atop the covered ice barge's after cabin always made me think of Holland. After passing the city of Hudson on the north shore of the river, the valley widened and the river narrowed, becoming low marshland as we approached Albany and Rensselaer, which were on opposite sides of the Hudson. This was the destination of the large tow which had consisted of many types of barges and canal boats when it had left New York City forty-eight hours earlier. By the time we arrived at Albany, the tow consisted mostly of canal boats. Along the river we had dropped off ice and sand barges, brick, stone, and cement barges, and some barges to be repaired at the Rondout and Kingston boatyards. At that time many of the industries along the river used different types of barges to ship their products to New York City." If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's Note: These are excerpts taken from pages 55-58 of "Canal Boatman: My Life on Upstate Waterways" by Richard Garrity, published by Syracuse University Press, 1977. "Departing from Tonawanda in midsummer, with two boat loads of lumber consigned to the Steinway piano factory in Brooklyn, we made a trip over the Erie Canal and down the Hudson River to New York City that I recall with much pleasure. It was 1909. I was six in August and was then old enough to be a wide-eyed and interested observer of everything, from the time we were put in the Hudson River tow at Albany, until we returned there eight days later. The steersman had been laid off when we arrived at Albany. My Uncle Charles, mother's younger brother who was driving our mules that summer, was put in charge of the head boat. My father and mother, and my older brother Jim, myself, a younger sister, and a baby brother were on the second boat, the "Sol Goldsmith". Before the start of a tow down the Hudson it was necessary to assemble and make up the tow as the canal boats arrived at Albany. I was told by older boatmen that in the early days when canal shipping was very busy, the tows were made up on the Albany and Rensselaer side of the river, but in my day they were made up only on the Rensselaer side of the river below the bridges. This eliminated the risk of the large two striking the Albany-Rensselaer bridge piers when starting down the river. Nor did it interfere with the Albany harbor traffic while being assembled. Once the tow was underway it was a period of relaxation for the boatmen. No steersmen were needed, since the tugs guided the boats. There would be no locks to pass through or time spent caring for animals as the teams were let out to pasture in the Albany vicinity until the boats returned from New York. Only the lines holding the boats together were to be inspected and kept tight. The boats would be kept pumped out, and that was it until the tow reached New York. This would take about 48 hours. Many of the boatmen did odd jobs, such as splicing lines, caulking, painting decks and cabin tops, and handling other small repair jobs. They also visited back and forth. I enjoyed going with Father when he visited other boatmen in tow, because I liked to hear them talk of other canal men they knew, and to hear them tell of things that had happened to them while going up and down the canal. My first visit with him aboard a "Bum Boat" that came out to the two opposite Kingston was a very satisfying event, for I never expected to be eating fresh ice cream, purchased going down the middle of the Hudson River. The Bum Boats sold – at regular retail prices to the boatmen – fresh meats, baked goods, eggs, soft drinks, candy, ice cream, and other such commodities. Coming alongside, it hooked onto our tow while the boatmen when aboard and bought what they wanted, including cold bottled beer. The small canopied Bum Boats were steam powered. They stayed alongside until we met another river tow going in the opposite direction. Leaving us, they tied onto the other two and returned to their starting point. They "bummed" a tow from a fleet going down the river and up the river; hence the name Bum Boat. When our tow arrived at New York I was amazed at the never-ending flow of harbor traffic. … After unloading the lumber for the Steinway piano factory in Brooklyn, we were towed to the canal piers on South Street at the foot of Manhattan Island. Here we waited a few days for orders from an agent who was to secure loads for our boats for the return trip to Tonawanda. My brother Jim, who was almost two years older than I, was entrusted to take me sightseeing along the busy streets bordering the waterfront. We visited the nearby Fulton Street fish market, a very busy place, and strolled by the stalls amazing by all the different kinds of saltwater fish brought in by the fishing fleet. We walked back along bustling South Street, which was always a beehive of activity due to the arrival and departure of the many tugs, barges, and other kinds of vessel traffic. Most of the business places along here catered to waterfront customers. In this area there were many push-carts selling all kinds of merchandise and food. We bought fresh oysters and clams on the half shell for a penny apiece. Hot dogs were a nickel (they were called Coney Island red hots), and many other items of ready-to-eat food and candy could be found at prices only to be had along the waterfront. That evening we were told that two loads of fine white sea gravel consigned to the Ayrault Roofing Company in Tonawanda had been secured for the return trip west. Early the next morning, a small steam tug hooked on to our two empty boats and towed us up the East River, though through the Hell Gate. After a few hours' tow on Long Island Sound we arrived at Oyster Bay and were moored at the gravel dock, ready to load. Two days later we were back at the South Street piers waiting to be placed in the next westbound Hudson River tow." If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's note: The following text is from the "Brooklyn Standard-Union" newspaper August 21, 1891. Thank you to Contributing Scholar George A. Thompson for finding and cataloging this article. The language, spelling and grammar of the article reflects the time period when it was written. On a Canal Boat. How Men, Women and Children Live Down in the Cabin – Babies Born and Die on Board – In Season and Out of Season the Cabin in the Family Home – The Hard Lot of the Women. She was a small-featured woman, with very light blue eyes and her fair skin bronzed by the water. We were sitting on the roof of the cabin of her husband's canal boat, at the foot of Coenties Slip. "Yes, miss," she replied to my question, "I live and my husband and children live down stairs in that cabin, year in and year out. Two of my children, one boy and one girl, were born downstairs. One of them, the girl, died there two years ago, while the boat laid up for the winter at the foot of Canal Street." Here the poor woman's voice faltered, as she took an end of her gingham apron to wipe the tears. "We thought the world of that little girl, Miss. She was as pretty as a picture, and gentle as a little lamb. I blame the doctor to this day for her death, that I do. The minute she was took sick my husband went for to bring him, and sez he, 'Oh, it's nothing, only the measles, so don't cher be alarmed." "I believe in me heart that the poor little thing was a-dying then. She died the next mornin', an' – an –' we buried her in the cemetery along with his father (her husband's) and mother. There was a hammock swinging between two poles on top of the cabin, near where we sat. In it lay a beautiful little golden-haired boy, fast asleep. It was the woman's baby, and whenever it was asleep up there she sat by his side, sewing or knitting, and keeping a close watch. It was a dangerous place for baby, for should he tumble out he would roll into the water. "Jimmie, Jimmie," suddenly called the woman, "come up here and watch your little brother, as I wants to go downstairs." Jimmie, who was evidently an obedient boy, … rushed upstairs from the cabin, banging the mosquito net doors after him as he came out. "This is my big boy," said the woman, looking up fondly at Jimmie. Boy-like, Jimmie barely glanced at me, contracted his brow and pulled the old straw hat down over his eyes as he took the seat his mother had vacated. "Come now, miss," said the woman, "I will show you how we live downstairs." We went down six steps covered with bright oilcloth and brass tips, all as clean and shiny as could be. The cabin was divided into three apartments – bedroom, kitchen and sitting room, in which there was an extra bunk for the grown-up daughter, who was away at the time. The kitchen was a mere hole, a stove and a few cooking utensils occupying the entire space. The bedroom was a little larger. It contained a three-quarter bed covered with linen of snowy whiteness, and one chair on which lay folded a number of quits and one pillow, doubtless to be spread on the floor for the big boy that night. The sitting or living room was about ten feet long and eight feet wide. The floor was covered with the same kind of oilcloth as that on the stairs; the furniture consisted of a bureau, two chairs, one rocking chair, of a green painted cottage bedroom suit, a round walnut table, a machine, and one extra brown chair. The woodwork was grained, and the ceiling and walls painted white. Two long closets, one for dishes and one for clothes, were built in one side of the wall; also a half dozen drawers. The walls were plentifully decorated with highly colored chromos, and these two texts: "Give us this day our daily bread." "Thou shalt not kill." In that crowded abode, a man, a woman, a girl of fourteen, a boy of twelve and a baby two years old lived, as the woman said, "year in and year out." I took the extra brown chair the woman offered me, which I presume they reserve for company. "Yes, mam, sometimes we do feel a bit crowded, but I reckon it's no worse than many of the folks who live in them awful tenement houses." "Do you know, mam, I could never feel contented in one of them places? We lives by ourselves here with no neighbors to pry into our business." "Oh, yes, some of us go to church whenever we are ashore on Sunday." "There is a Mr. McGuire that comes down here every Lord's day and preaches on the dock. He is 'Piscopal, I think, but he is a fine man all the same." "We are Catholic, but we believe in letting everybody enjoy their own religion. My husband and me ain't no ways bigoted." "Oh, certainly, my children goes to school in winter. We always spend the winter in New York, and it is there that we send them to the public school." "The children in New York are very rude. They have a way of teasing mine for living on a boat. 'And do yez eat off the floor?' they say to Mamie sometimes. Yes, them children behave very badly." While the woman was talking the screen door opened with a jerk, and a girl dressed in a deep green woolen frock and a black straw sailor hat came down the cabin stairs. "This is my daughter," said the woman. "She has been visiting in Brooklyn." The girl, who had a rather pleasant face, smiled at me without bowing, and then sat down and stared. The woman, addressing the girl, said: "This lady wanted to see how people lived on a canal boat, so I brought her down. We like to have company once in a while," she went on, "for it's lonely enough at times, the dear knows." The girl continued to stare, as she kept playing with the elastic on her hat. The boat we were on ran between New York and Canada, [editor's note: via the Champlain Canal] and the woman, who was of a descriptive turn of mind, told me just how the trips were made. It took forty-eight hours for a tug to tow them to Albany; from Albany they went to Troy, and then for sixty-eight miles the horses pulled the boat up the canal. On the other end of the canal a Canadian tug brought them to their destination. After telling me all this we went up on deck again, and there the woman explained how she managed her washing. I saw a wash-board lying on the floor of a small rowboat that stood alongside of the hammock in which the clothes were washed. The "men folks," the woman said, usually carried the water, and she did the rest. Then clothes were dried underneath the canvas. I next asked the woman what her husband carried on his boat. "He carries different things," said she. "This time he carries what they calls 'merchandise.'" Just then a wagonload of rosin came to be packed on board. I left the family standing by the side of the baby, as I went farther up the deck, where I engaged in conversation with the captain of another canal boat. I found him just as accommodating and as obliging as the woman I had talked with. "Certainly, mam, you can go down in the cabin. You will find my wife there, and she'll talk to you." This man and wife were not so cramped as some of their neighbors, for they had no children. I found the man's wife a clever woman, but not nearly so philosophical about living on a canal boat as her neighbor. She told me that this was her third summer on the water, and that it was going to be her last. She spent most of her time making fancy work for her friends. Her apartments were clean as wax, and judging from the arrangement of the furniture, curtains and pictures, she was a woman of some refinement. She was a great sight-seer, too. She always made it a point to visit the places of interest in all cities where they stopped. She had been to a great many downs between Albany and Philadelphia. She had been married to the captain fifteen years, but she could never accustom herself to life on a canal boat. She would be happier on land. On either side of the two boats were a dozen other boats, some loading and some unloading their freight, and on all of them were women and on most of them children. But the thought of human beings spending most of their time penned up as the women and children on these boats are obliged to be, recalls once more that timely question: "Does one-half of the world know or care how the other half lives?" That more of these canal boat children are not drowned is a wonder, and that more of the women do not lose their times is equally surprising. It is sad to reflect on the emptiness and monotony of their lives. – [original article written by Emma Trapper, in Brooklyn Standard-Union.] (Editor's note: Canalboat families worked hard but some found life aboard these boats wholesome and at times pleasurable. While difficult to measure and compare, the standard of living among boat families on the canals was likely higher than that of many urban laborers.) If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's note: The following text is from the "Register of Pennsylvania", August 14, 1830. Thank you to Contributing Scholar George A. Thompson for finding, cataloging and transcribing this article. The language, spelling and grammar of the article reflects the time period when it was written. A Trip On The Delaware & Hudson Canal To Carbondale. New York, August 2d, 1830. Mr. Croswell -- I perceive by the paper, that a packet boat commences this day, to run regularly for the remainder of the season, on the Delaware and Hudson canal. Among the pleasant and healthy tours that are now sought after, I would strongly recommend a trip on that canal. It leads from Bolton, on the waters of the Hudson and Kingston Landing; to Carbondale on the Lackawanna, which falls into the Susquehanna. I had the satisfaction not long since to visit that country, and I was delighted with the beauty and grandeur of the scenery, and the noble exhibition of skill, enterprize and rising prosperity, which were displayed throughout the course of that excursion. This great canal, though seated in the heart of the state, seems to be almost unknown to the mass of our tourists. Its character, execution and utility, richly merit a better acquaintance. It commences at Eddyville, two miles above Kingston, and we ascend a south-west course along the romantic valley of the Rondout, and through a rich agricultural country in Ulster county, which has been settled and cultivated for above a century. the Shawangunk range of mountains hangs on our left; and as we attain a summit level at Phillips or Lock Port, 35 miles from the commencement of the canal, after having passed through 54 lift-locks, extremely well made of hammered stone laid in hydraulic cement. The elevation here is 535 feet above tide water at Bolton, and the canal on this summit level of 16 miles, is fed principally by the abundant waters of the Neversink, over which river the canal passes in a stone aqueduct of 324 feet in length; and descends through 6 locks to Port Jervis, at the junction of the Neversink and Delaware rivers, and 59 miles from the landing. The canal here changes its course to the north-west, and ascends the left bank of the majestic Delaware, through a mountainous and wild region, to the mouth of the Laxawaxen [sic], at the distance of 22 miles from Port Jervis. In this short course the canal is mostly fed by the large stream of the Mongauss, which it crosses, and in several places and for considerable distances, it is raised from the edge of the bed of the Delaware, upon walls of neat and excellent masonry, and winds along in the most bold and picturesque style, under the lofty and perpendicular sides of the mountains. the Neversink, the Mongauss, the Lackawaxen [sic] and the Delaware were all swollen by the heavy rains when I visited the canal, and they served not only to test the solidity of the work, and the judgment with which it was planted, but to add greatly to the magnificence of the scenery. At the mouth of the Lackawaxen we crossed the Delaware upon the waters of a dam thrown across it, and entered the state of Pennsylvania, and ascended the Lackawaxen, through a mountainous region the farther distance of 25 miles to Honesdale, where the canal terminates. This new, rising and beautiful village, is situated at the junction of the Lackawaxen and Dyberry streams, and is so named out of respect to Philip Hone, Esq. of New York, who has richly merited the honor by his early, constant and most efficient patronage of the great enterprize of the canal. The village is upwards of 1000 feet above tide water at Bolton, and at the distance of 103 miles according to the course of the canal. There are 103 lift and two guard locks in that distance, and the supervision of the locks and canal, by means of agents or overseers in the service of the company, and who have short sections of the canal allotted to each, appeared to me to be vigilant, judicious and economical. The canal and locks, by means of incessant attention, are sure to be kept in a sound state and in the utmost order. The plan and execution of the canal are equally calculated to strike the observer with surprise and admiration. He cannot but be deeply impressed, when he considers the enterprising and gigantic nature of the undertaking, the difficulties which the company had to encounter, and the complete success with which those difficulties have been surmounted. This is the effort of a private company; and when we reflect on the nature of the ground, and the character and style of the work, we can hardly fail to pronounce it a more enterprising achievement than that of the Erie Canal. I hope and trust it may be equally successful. We found the most busy activity on the canal, and it was enlivened throughout its course by canal boats, (of which there were upwards of 150) employed in transporting coal down to the Hudson. At Honesdale a new and curious scene opens. Here the rail-way commences, and it ascends to a summit level of perhaps 850 feet on its way to Carbondale, a distance of 16 miles and upwards. It terminates in the coal beds on the waters of the Lackawanna, at the thriving village of Carbondale. The rail-way, is built of timber, with iron slates fastened to the timber rails with screws, and in ascending the elevations and levels, the coat cars are drawn up and let down by means of stationary steam-engines, and three self-acting or gravitating engines moving without steam. Nothing will more astonish and delight a person not familiar with such things, than a ride on this rail-way in one of the cars. A single horse will draw 16 loaded cars in most places, and in one part of the distance for five miles the descent is sufficient to move the loaded cars by their own weight. A line of ten or a dozen loaded cars, moving with any degree of velocity that may be required, and with their speed perfectly under the command of the guide or pilot, is a very interesting spectacle. I don't pretend to skill or science on the subject to canals, rail-ways and anthracite coal. I speak only of what I saw and of the impressions which were made upon my mind. It appears to me that all persons of taste and patrons of merits, whose feelings are capable of elevation in the presence of grand natural scenery, and whose patriotism can be kindled by the accumulated displays of their country's prosperity, would be glad of an opportunity to see these beauties of nature and triumphs of art to which I have alluded. "A Trip On The Delaware & Hudson Canal To Carbondale." Register of Pennsylvania. August 14, 1830. 111—112. 1830-08-02 -- A Trip on the Delaware & Hudson Canal to Carbondale If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's note: The following text is from the August 3, 1831 issue of "Cabinet" , Schenectady, New York. Thank you to Contributing Scholar George A. Thompson for finding and cataloging this article. The language, spelling and grammar of the article reflects the time period when it was written. Fortune Telling – A system of fraud has been lately followed in this city, to a considerable extent, which is important the public should have a knowledge of, that they may guard against impositions. A man named Pierce has been in the practice of enticing people from the country to houses on pretence of getting their fortunes told, and he would then fleece them out of their money. His practice was to leave the city until he ascertained that the cheated person had gone off, and he would then return and practice his villanies on others. Complaints had sometimes been made to the police officers, but they could never get Pierce, until the complainant had left the city, and there was then no evidence to convict him. But last week the biter got bit. One or two weeks ago, a man from Vermont, named Carey, who had engaged a passage to the west, in a canal boat, was accosted by Pierce, who told him he was going in the same boat, and by his attentions to him become ingratiated in his favor. He proposed to C. to go and get their fortunes told. In going across one of the pier bridges, they met a man named Brown; P. pretended to be a stranger to him, and asked him where there was a fortune teller. B. said he was one. They then went into a store on the pier, where B. commenced telling P's fortune, and the latter expressed his great astonishment that he could tell him so correctly, how old he was and where he was born, & c. He then urged Carey to have his fortune told, but C. declined. P. and B. then began to bet on the turning up of cards. Finally B. offered to bet $50 that he would turn up a particular card after the pack had been shuffled by his adversary. Pierce said he had but $210 with him, and after much urging, he persuaded Carey to lend him forty dollars. The particular card was not turned up, when P. seized the money and immediately left the room. Carey could not find him afterwards. He made complaint to the police, but Pierce could not be found, having gone off as usual. The police advised Carey to leave the ciy in the boat in which he had engaged to go to the western part of the state, but to stop a few miles out for town for a short time, and advise where he could be found, in case they secured Pierce. The plan succeeded; Pierce, having ascertained that Carey had gone, and supposing him far away from the city, returned, intending no doubt to renew his schemes on others. But the officers of Justice laid their hands on him, and having obtained the attendance of Carey, the cunning Mr. Pierce was committed to prison, and will be tried next week. He has been taught the lesson that simple honest is better than the deepest craft. Brown left the city at the same time with Pierce. He also has since been arrested. Albany Gazette If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Happy Labor Day! For today's Media Monday, we thought we'd highlight this recent lecture by Bill Merchant, historian and curator for the D&H Canal Historical Society in High Falls, NY. "Child Labor on the D&H Canal" highlights the role of children on one of the biggest economic drivers of the Hudson Valley in the 19th century. Child labor was a huge issue in 19th and early 20th century America (learn more) throughout nearly every industry, including the maritime and canal industries. Although many canal barges were operated by families, many were also operated by single men who exploited orphans and poor children, often with fatal results. Children were most generally used as "drivers," also known as hoggees, who walked with or rode the mule or horse who pulled the barge through the canal. Work was long, often sunup to sundown or even longer, as the faster barges could get through the canal, the faster they could return and pick up a new cargo, thus making more money. The Kingston Daily Freeman reported a Coroner's Inquests on July 18, 1846, which recorded several deaths related to Rondout Creek and the D&H Canal, including a young boy. It is transcribed in full below: Coroner's Inquests. On the 11th, Coroner Suydam [sp?] held an inquest at Rondout on the body of Joseph Marival, a colored hand on board the sloop Hudson of Norwich, Ct. He went in the creek to bathe, and was accidentally drowned. The same officer held an inquest at [?] Creek Locks on the body of Henry Eighmey, on the 15ht, drowned in the canal by a fall from a boat about noon. We have record of a third by Mr. Suydam, held at Rosendale on the 12th, on the body of Andrew J. Garney, a lad of ten years old, a rider, who it was supposed fell from his horse into the canal about day break of that morning, a verdict conformable being rendered. In connection with the last case, we would remark, that the crew consisted of one man with the driver who was drowned. That the boat had been running all night [emphasis original]; that about three o'clock in the morning the man spoke to the land and was answered, and that some time afterwards he missed him, and concluded he must have fallen into the canal. Is there any thing strange in the fact that a lad of ten years, worn down with the fatigues of a long day and a whole night in the bargain, should drop into another world? Now we do not mean to mark this as a singular case, by any means. It is but one of the like occurring almost daily on the canal. Lads are hired at a mere pittance, and men are determined to get as much work out of them as possible, without the least regard to health, comfort, or safety. The poor children are toiling from daylight to dark, and if in addition they are forced to nod all or part of the night, the consequent sleep and death is nothing to be wondered at. We would call attention to this subject on the part of those who may able to devise a mode of reaching such cases. Nor would it be out of place in the Coroner's jury in the next instance should state the whole [emphasis original] truth in the verdict. Most laborers on the canal were paid at the end of the season, but it was not uncommon for unscrupulous barge operators to cheat the boys of their wages and abandon them in random canal towns. Even when working with their families, children who lived aboard barges sometimes had hard lives. Although the Delaware & Hudson Canal closed in 1898, children and families continued to work on the newly revamped New York State Barge Canal system and canals in Ohio and elsewhere into the mid-20th century. In 1923, Monthly Labor Review published an article entitled "Canal-boat Children," which looked at the labor, education, and living conditions of children on canal boats. Of particular interest was safety, as the threat of drowning or being crushed in locks was near-constant. Still, many families were able to make decent livings aboard canal barges, until tugboats took over canal barge towing in the mid-20th century. To learn more about New York Canals, visit the Hudson River Maritime Museum's exhibit "The Hudson and Its Canals: Building the Empire State," or visit the newly revamped D&H Canal Museum in nearby High Falls, NY. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Welcome to Sail Freighter Fridays! This article is part of a series linked to our new exhibit: "A New Age Of Sail: The History And Future Of Sail Freight In The Hudson Valley," and tells the stories of sailing cargo ships both modern and historical, on the Hudson River and around the world. Anyone interested in how to support Sail Freight should also check out the Conference in November, and the International Windship Association's Decade of Wind Propulsion. The Vermont Sail Freight Project was first conceived of in 2012, and resulted in the launch of the Ceres in mid 2013. Just short of 40 feet long, made of plywood, she had a Yawl rig and leeboards. Leeboards, which are separate drop keels that mount to the sides rather than center of the boat, have been out of use in the US for almost 250 years. Their use aboard Ceres made her very unique looking, and unique to sail as well. With a cargo capacity of only about 10-12 tons, she was not luxurious or large, but she was a capable sailor whose rig could be folded down for passing under the low bridges of the Champlain Canal. She was loosely based on similar sailing canal barges that operated on Lake Champlain and traveled the canal throughout the 19th century. The replica Lake Champlain canal schooner Lois McClure is one example of these historic vessels. Ceres' sailing rig was more inspired by the British sailing barges that operated on the Thames River from the 17th to 20th centuries in England. She was built in the farmyard of the project's founder, Erik Andrus, and launched in Vergennes, VT. After some initial tests, she was used to carry farm produce cargos in 2013 and 2014 from the Champlain Valley to New York City. In 2013, she visited the Hudson River Maritime Museum, hosted a farmer's market with produce from the Champlain Valley, and provided education programs for local school kids. The endeavor gained a lot of press, and was mostly successful, but in the end, the demands of time and attention were too much for a group of volunteers to handle. The project ended in 2014, and Ceres was sold for use as a tiny house in 2018. The rig is still in a barn outside Vergennes, waiting for another boat to be built and launched. Though the project wasn't long-lasting, it was ambitious and brought much-needed attention to the possibilities of sail freight in the US. The Schooner Apollonia was directly inspired by the VSFP, and Maine Sail Freight's single 2015 voyage was in response to the Ceres' precedent as well. Aside from a lot of press coverage and a few sail freight ventures, the VSFP also inspired my Master's Thesis on the revival of Sail Freight and what it would take to make it a reality in the US. Erik Andrus graciously served on the thesis committee for this work, and contributed invaluable insights and materials which will benefit the other efforts which are rebuilding the sail freight economy. You can read more about the Vermont Sail Freight Project here. If you'd like to see some artifacts from the Ceres, there will be a few on display in the exhibit. AuthorSteven Woods is the Solaris and Education coordinator at HRMM. He earned his Master's degree in Resilient and Sustainable Communities at Prescott College, and wrote his thesis on the revival of Sail Freight for supplying the New York Metro Area's food needs. Steven has worked in Museums for over 20 years. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's note: the following engraving and text were originally published in Gleason's Pictorial Drawing Room Companion, December 25, 1852. Thanks to volunteer researcher George A. Thompson for finding and cataloging this article. The article was transcribed by Sarah Wassberg Johnson, and includes paragraph breaks and bullets not present in the original, to make it easier to read for modern audiences.  "Canal Boats on the North River, New York" by Wade, "Gleason's Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion," December 25, 1852. Note the sail-like signs for various towing lines and destinations, as well as the jumble of lumber and cargo boxes on the pier at left, waiting to be loaded onto the canal boats (or vice versa). Next to the immense foreign export and import trade, comes the inland trade. The whole of the western country from Lake Superior finds a depot at New York. The larger quantity of produce finds its way to the Erie Canal, from thence to the Hudson River to New York. The canal boats run from New York to Buffalo, and vice versa. These boats are made very strong, being bound round by extra guards, to protect them from the many thumps they are subject to. They are towed from Albany to New York - from ten to twenty - by a steamboat, loaded with all the luxuries of the West. The view represented above is taken from Pier No. 1, East River, giving a slight idea of the immense trade which, next to foreign trade, sets New York alive with action. We subjoin from a late census a schedule of the trade; the depot of which, and the modus operandi, Mr. Wade, our artist, has represented in the engraving above, is so truthful and lifelike a manner. In 1840, there were

If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

|

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 [email protected] Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |