History Blog

|

|

|

|

|

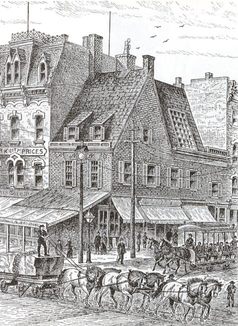

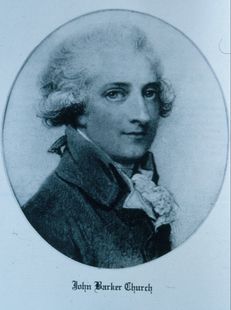

Schuyler Mansion State Historic Site has been open to the public since October 17, 1917 and will be celebrating its 100th anniversary this season. The home was built between 1761 and 1765 by Philip Schuyler of Albany who, after serving in the French and Indian War, went on to become one of four Major Generals who served under George Washington during the American Revolution. Prominent for his military career, as a businessman, farmer, and politician, Philip was the main focus of the museum when it opened in 1917. Over the last hundred years, however, the narrative told by historians at the site has expanded to emphasize the roles of Philip’s wife Catharine Van Rensselaer Schuyler, their eight children (five daughters; three sons), and nearly twenty enslaved men, women, and children owned by the Schuylers at their Albany estate. Since March was Women’s History Month, I am pleased to set aside Philip Schuyler, and instead bring you the history of the women of Schuyler Mansion – Catharine Schuyler and her five daughters Angelica, Elizabeth, Margaret, Cornelia, and Catharine (henceforth Caty to avoid confusion with her mother). Some of those names will sound familiar to fans of the Broadway show Hamilton: An American Musical. The oldest daughters, Angelica, Elizabeth, and Margaret “Peggy” Schuyler, born in 1756, ‘57, and ‘58, feature heavily in the plot because second daughter Elizabeth married Alexander Hamilton, America’s first Secretary of the Treasury, in 1780. It is largely through Elizabeth’s efforts that so much information exists about Alexander Hamilton, Philip Schuyler, and the rest of the family. Women were often the family historians of their time, collecting letters and documents. Elizabeth was particularly tenacious in this role. Unfortunately, since women’s actions were not considered relevant to the historical narrative (and perhaps due to some degree of modesty from the female collectors), sources by and about women were not always preserved. Through careful inspection of the documents that remain, however, we can piece together quite a lot about these six women.  Philip Schuyler's childhood home - a 17th-Century Dutch structure where the eldest daughters were raised before moving to Schuyler Mansion. Albany in the 18th-Century still reflected its' Dutch roots more than its' English government. Philip Schuyler's childhood home - a 17th-Century Dutch structure where the eldest daughters were raised before moving to Schuyler Mansion. Albany in the 18th-Century still reflected its' Dutch roots more than its' English government. For the Schuylers, documentation started young, with receipts and letters describing the girls’ education. In the period, core literacy was most often taught at churches where basic reading and writing were a means to an end in teaching scripture. This holds true for the Schuylers. In 1764, when Angelica was 8 years old, Philip purchased “cathecism books more for Miss Ann”. Philip additionally paid for lessons in French, dancing, geography, history, writing, and arithmetic. In combination with references to music, ornamental embroidery, and the “women’s work” which the girls most likely learned from Catharine, these lessons constituted every subject deemed appropriate for women by contemporary educational philosopher Benjamin Rush, and more. This family was well educated even amongst their peers. Catharine’s education, however, remains mysterious as no letters in her handwriting exist. Given her social status, it is unlikely that she was illiterate. However, it is possible that she was literate only in Dutch, as approximately half of Albany still spoke Dutch as their first language. Anne Grant (a contemporary of Catharine’s) described in A. Kenney’s Gansevoorts of Albany: “In the 1750s girls learned to read the Bible and religious works in Dutch and to speak English more or less, but a girl who could read English was accomplished; only a few learned much writing.”  This portrait of youngest daughter Catharine Schuyler shows Caty at about 12-15 years old. She is sitting in front of a piano forte. Instruments were expensive, but music was considered a fine accomplishment for ladies in families who could afford it. This portrait of youngest daughter Catharine Schuyler shows Caty at about 12-15 years old. She is sitting in front of a piano forte. Instruments were expensive, but music was considered a fine accomplishment for ladies in families who could afford it. Knowing women’s childhood education is critical to our understanding of their adult lives. Even today, education molds children to fit the ideals of the culture they live in and therefore shows parents’ aspirations for their children. In the 18th Century, the ideal for women of this social class can be defined by four main roles: wife, mother, household manager, and social manager. By educating his daughters in dance, music and etiquette, Philip Schuyler prepared them for the wealthy social scene where they would meet potential suitors. By having them learn French, they could read philosophies and poetry and other refined subjects that would be impressive to the educated elite that Schuyler hoped those suitors would be. Meanwhile, Catharine taught them the household work that would be required of them once married. Historically, women have been defined primarily by their spouses. It is a mistake to do so, however, marriage was exceptionally important for women in the 18th-Century. Under English government, women had no political rights and very limited legal, economic, or property rights. An adult woman’s power came from the influence she had over her spouse, and the influence she had over the next generation through the training of her sons. As such, at the start of the 1700s, 93% of women in the Northeast were married. This declined to 78% by century’s end, which likely correlated with a growing population of women, rather than declined need or desire to marry. While arranged marriages were fading out of style with non-nobility by the mid-18th-Century, wedding arrangements still looked quite different from today. In more liberal households, as the Dutch tended to be, a woman had a fair amount of say in who she was to marry, but only so long as she was marrying from within an appropriate social circle. Parental permission was still required and a suitor who brought in political or property assets was preferred. Romantic love (or attraction - the term “romantic” was not yet used as we think of it today) as a prerequisite for marriage was gaining popularity, but was not considered necessary. Marriage was often treated as an economic pact. If love existed or developed, it was a bonus. There are two marriages in the Schuyler family that are key to understanding this family’s dynamics - Philip Schuyler’s marriage to Catharine Van Rensselaer in 1755, and eldest daughter Angelica’s marriage to John Barker Church in 1777.  Catharine grew up in the heart of the Van Rensselaer property in Greenbush, now the city of Rensselaer. Her parents' home, Crailo, still stands as another New York State Park. Catharine grew up in the heart of the Van Rensselaer property in Greenbush, now the city of Rensselaer. Her parents' home, Crailo, still stands as another New York State Park. Philip and Catharine’s marriage mostly fit the cultural ideal described above. Both were fourth generation Dutch, meaning that their great-grandparents were the first to come from the Netherlands in the mid- 1600’s. Philip’s family made its fortune in the beaver fur trade and supplemented their income through land speculation and marriage. Meanwhile, Catharine’s family came over as part of the Dutch Patroon system. Akin to a feudal system in some ways, Patroonships gifted land to wealthy Dutch families in order to colonize New Netherland, which later became New York. By the time of Catharine’s birth, her father owned more than one hundred and fifty thousand acres of land throughout the colony. Not only was the couple from the same wealthy elite social circle and approved of by both families, they had a seemingly romantic courtship. In letters before their marriage, Schuyler asked his friend Abraham Ten Broeck to pay his regards to “Sweet Kitty VR” if he should see her.  Philip and Catharine likely expected their children would also marry with wealth, education, and family approval in mind. Angelica’s marriage broke those expectations when, in 1777, she married an elegant young commissar who called himself John Carter. Carter came to the home to settle military accounts with Philip Schuyler. While Carter looked the part of the wealthy, well-educated man, Philip knew nothing of Carter’s family and worried about his connection with Angelica. No one could tell Philip more about “Carter”, because this was an assumed identity. The man was actually John Barker Church, a broker from a prominent family in England. Church fled to the colonies to escape gambling debt, and possibly fallout from a duel. Either unconcerned with her suitor’s background, or uninformed of it, Angelica married John Barker Church without parental permission. As a result, she was disowned and forced to take up residence with her maternal grandparents in Greenbush. She stayed with them only two weeks before her grandfather coaxed Philip and Catharine to meet with the couple and forgive them. It is unclear if Church revealed his identity to the Schuylers at that time, as the couple continued to be known as the “Carters” until the end of the war. After this marriage, Philip no longer had the confidence that his children would marry under the ideals of the time, and because he was so quick to forgive Angelica, his children saw this as precedence. At least three more of the eight children eloped. Second daughter Elizabeth married with permission, but Angelica’s elopement clearly still weighed heavily on Philip’s mind when he responded to Alexander Hamilton’s request for Elizabeth’s hand in February of 1780: “Mrs. Schuyler[...] consents to comply with your and her daughter’s wishes. You will see the impropriety of taking the dernier pas [fr: last step] where you are. Mrs. Schuyler did not see her eldest daughter married. That gave me also pain, and we wish not to experience it a second time.”  The formal parlor at Schuyler Mansion where Elizabeth Schuyler married Alexander Hamilton on December 14, 1780. The formal parlor at Schuyler Mansion where Elizabeth Schuyler married Alexander Hamilton on December 14, 1780. The formal parlor at Schuyler Mansion where Elizabeth Schuyler married Alexander Hamilton on December 14, 1780 Hamilton was far from Schuyler’s ideal. He was an orphan raised in poverty in the Caribbean with no land, money, or family ties. And yet, Schuyler hesitantly said yes. Perhaps it was only Hamilton’s military career under George Washington that earned Philip’s approval. Or, perhaps the question lurked at the back of Philip’s mind: “if I say ‘no’… will they marry anyway?” Philip maintained control over the situation by asking the pair to marry at Schuyler Mansion, forcing them to wait until Hamilton could take military leave. The couple married in the formal parlor of Schuyler Mansion on December 14, 1780. The next in line was Margaret, nicknamed Peggy. Unlike her sisters, Peggy married close to home in 1783. Stephen Van Rensselaer was a cousin on her mother’s side. The relationship was very near the ideal set forth by their parents. It strengthened the family’s connection with one of the wealthiest Dutch families in Albany. In fact, after inheriting the bulk of the Van Rensselaer estate at 21 years old, including his land holdings - approximately 1/40th of New York State – and accounting for inflation, Stephen ranks 10th on Business Insider’s list of the wealthiest Americans of all time. There are rumors that Peggy and Stephen eloped, but very little evidence to support it. A relative of Stephen’s reacted with surprise that Stephen, then 19, married so young, especially since his bride was 25, but there was no surprise or outrage from either parents. There was no question that this was a powerful match. The next Schuyler daughter, Cornelia, was 17 years younger than Peggy, but despite the age gap, the influence of Angelica’s marriage still held power. Cornelia eloped in 1797 with Washington Morton, an attorney from New York who appears to have attempted to gain parental permission but, in his own words: "Her mother and myself had a difference which extended to the father and I had got my wife in opposition to them both. She leapt from a Two Story Window into my arms and abandoning every thing [sic] for me gave the most convincing proof of what a husband most Desire [sic] to Know that his wife Loves him."  Washington Morton fit the economic expectations of the Schuylers, but his irreverent sense of humor & flippant behavior diminished his worthiness in Philip’s eyes. Washington Morton fit the economic expectations of the Schuylers, but his irreverent sense of humor & flippant behavior diminished his worthiness in Philip’s eyes. This description is hyperbole, since Cornelia more likely snuck out a door than leapt out a window. It is possible that Angelica gave her young sister advice or even direct aid with her elopement. Angelica had recently returned from Europe and Morton wrote that they were married by the same Judge Sedgwick who had married Angelica to John Barker Church. Philip forgave Cornelia quite quickly, but never really found a place in his heart Morton, who became Schuyler’s least favorite in-law. Philip wrote to his son of Morton: Washington Morton fit the economic expectations of the Schuylers, but his irreverent sense of humor & flippant behavior diminished his worthiness in Philip’s eyes. "his conduct, whilst here has been as usual, most preposterous. Seldom an evening at home, and seldom even at dinner - I have not thought it prudent to say the least word to him[...]as advice on such an irregular character is thrown away." Young Caty did better in Schuyler’s estimation, but her marriage was also an elopement. She married attorney Samuel Bayard Malcolm not long after her mother’s death in March of 1803. However, given descriptions of the big reveal, it is likely that the couple has already married, but Catharine’s death prevented Caty from being able to tell her father. Schuyler accepted Malcolm soon after, so when Schuyler died the next year, Caty would have had a clean conscience. Unfortunately, Malcolm died in 1817. So as not to remain a powerless widow, Caty remarried in 1822 to James Cochran, a prominent attorney and politician who was the son of Washington’s personal physician. Cochran was also her first cousin. Marrying a cousin was seen as a safe match, particularly for widows and widowers, as it consolidated wealth amongst family and one could trust that one’s children would be accepted since the new spouse was kin.  The Schuyler women had birthing rates similar to the averages for their time period. Margaret and Cornelia Schuyler died young (42, and 32 respectively). Caty's reflect two marriages, as her first husband died while she was still of child-birthing age. The Schuyler women had birthing rates similar to the averages for their time period. Margaret and Cornelia Schuyler died young (42, and 32 respectively). Caty's reflect two marriages, as her first husband died while she was still of child-birthing age. The Schuyler women had birthing rates similar to the averages for their time period. Margaret and Cornelia Schuyler died young (42, and 32 respectively). Caty's reflect two marriages, as her first husband died while she was still of child-birthing age. For women, a marriage contract provided necessary economic stability. Spending too long outside of the contract resulted in a lack of security for oneself and one’s family. By marrying well, men could also gain economic ground and benefit from the production of heirs. A woman could have a lot of influence on the early education of these heirs since she was the main caretaker until a child was old enough to go outside the home. For women, childrearing was an all-consuming part of their life after marriage. On average, women in the mid to late 18th century gave birth once every other year from her marriage until death or menopause, whichever came first. Infant mortality rates were high, with approximately half of children dying before reaching the age of 3. Even with this mortality rate, birthrates still averaged eight surviving children per mother! Towards the end of the century, women began having fewer births with slightly lower infant mortality rates – averaging 6 surviving children per mother. Catharine Schuyler fit these averages. According to the family bible, Catharine gave birth to fifteen children. Eight survived to adulthood. Her last child came when she was 47 years old. In other ways, Catharine was unusual - among the seven children who didn’t survive infancy, there was one set of twins and one set of triplets. Multiple births were rare, and the fact that Catharine survived those dangerous births was a testament to her health. As one can imagine this pattern was both physically and emotionally devastating for women. The majority of their lives were spent being pregnant, recovering from pregnancy, and taking care of young children, many of whom did not survive. Throughout this cycle, the Schuyler women were also managing the household and the social affairs of the family. Catharine thrived as a manager and Philip seemed to put a great deal of trust in her logistic abilities. She made purchases for the home, received orders, and was responsible for decisions concerning the estate in Schuyler’s absence. Aided by Schuyler’s military mentor John Bradstreet, she also acted as overseer for the initial construction of Schuyler Mansion while her husband was on business in England.  Schuyler Mansion once had 125 total acres with 80 acres of farmland and a series of back working buildings. Catharine was often placed in charge of the property in Schuyler's absence and managed the slaves who worked in the household. Schuyler Mansion once had 125 total acres with 80 acres of farmland and a series of back working buildings. Catharine was often placed in charge of the property in Schuyler's absence and managed the slaves who worked in the household. Schuyler Mansion once had 125 total acres with 80 acres of farmland and a series of back working buildings. Catharine was often placed in charge of the property in Schuyler's absence and managed the slaves who worked in the household. While attending to business, political, and military affairs, men were not home to prepare for or entertain high caliber guests whose support was often needed to maintain said business, political and military affairs. It fell on Catharine and the girls to foster a social atmosphere for their home. They threw parties, called on other households, and were ready to receive unexpected visitors at any time – including, for instance, the more than twenty military visitors sent to the home when Burgoyne was taken “prisoner guest” after his surrender to General Gates at the Battle of Saratoga. Catharine also acted as an overseer for the unsung women of Schuyler Mansion – the enslaved servants. The head servant Prince, the enslaved women including Sylvia, Bess and Mary, and the children like Sylvia’s children Tom, Tally-ho, and Hanover, who helped serve within the home, all reported directly to Catharine. These women did the majority of labor within the home – cooking, cleaning, mending, laundry, acting as nannies when the girls travelled, and perhaps even producing the materials used for these tasks – like rendering soap and dipping candles. All this was done while raising their own families. Sources on the enslaved women of the Schuyler household are even sparser, of course, but we tell the stories we have and hope that we will someday know more. Documents do not always allow us to tell the full range of stories we would like to tell. Thankfully, the Schuyler women were accomplished. Though they did not always fit the ideals of their society perfectly, they made themselves a prominent part of it. They married well, managed their family’s social connections and households, and very importantly, raised children who valued history and valued preserving their family’s legacy. While there are many questions that we at Schuyler Mansion still wish to answer about these women, we are fortunate to have the sources to interpret their lives, not just during Women’s History Month, but year round. To get more stories about these women, visit Schuyler Mansion’s blog or visit Facebook for information on our upcoming “Women of Schuyler Mansion” focus tour. AuthorDanielle Funiciello has been a historic interpreter at Schuyler Mansion since 2012. She earned her MA in Public History from the University at Albany in 2013 and has been accepted into the PhD Program in History for Fall 2017. She will be writing her dissertation on Angelica Schuyler Church.

2 Comments

|

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 [email protected] Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |