History Blog

|

|

|

|

|

Editor's note: The following is from an August 23, 1911 publication by C. Meech Woolsey, Thank you to Contributing Scholar George A. Thompson for finding, cataloging and transcribing this article. The language, spelling and grammar of the article reflects the time period when it was written. ANCIENT MILTON FERRY. (By C. Meech Woolsey.) Scraps of History and Tradition About an Early Enterprise. The early history of this ferry is all tradition. About 1740, there was a ferry established across the Hudson river from a point on the west side a half mile south of what is the present steamboat landing at Milton, to some point at, or near, what is now the Gill place, or at what was Barnegat. What kind of vessel was then used can not now be determined, but was supposed to have been a row or sail boat of some kind. It was adequate to carry wagons, teams, cattle, etc. The country that now comprises the towns of Marlborough and Plattekill and some lands on the south, was early settled by English people who had previously settled in what is now Westchester county and Long Island, and children of such settlers. After 1720 and up to revolutionary times, large numbers of settlers poured into this part of the country. They brought their families, teams, cattle, and all their worldly goods with them. They crossed from the east side to the west side of the river by means of this ferry. They also kept up intercourse for many years with those they had left behind. This, I think, is the reason the ferry was established so early. A means of crossing was needed, so they provided some rude vessel that would answer the purpose. After this early means of crossing was in operation, people naturally came here to use the ferry for miles up and down the river on either side. My great, great grandfather, Richard Woolsey, was among these early settlers. He was born at Bedford, Westchester county in 1697, came here when a young man and purchased an original patent of land, granted by Queen Anne, of several hundred acres lying adjoining this ferry on the south, parts of which lands are now owned by me. He and his descendants left numerous traditions about this boat. It was in use and used by Richard Woolsey up to the time of his death in 1777, and at that time was burned at Barnegat and brought over by this ferry. Nicholas Hallock, the oldest man in the town, says he well remembers when a child, hearing his great uncle Edward Hallock, and his grandfather, Hull tell about using this ferry and how it was built, the way it was entered, etc. I cannot find any charter for it, or who was the first owner. In our ancient town records of road districts for the year 1779, I find as follows: "Nathanial Marker's District, No.1. Beginning at Major DuBois's north line, runs to Zadock Lewis's house at the crossroad leading to the ferry." and also, "William Woolsey's District. No. 5. Beginning at Lattemores ferry at the river, running south of Jeremiah Beagles in Latting Town." Benoni Lattemore owned the ferry at this time and had been the owner for some years previously. Afterward and some time prior to 1789 Elijah Lewis owned it. He had a dock and also carried on business there. It was claimed at one time that T---lis Anthony [paper damaged] owned it, and before him by one Van Keuren. These last two owners resided on the east side of the river. It is referred to in a map of the post road south of Poughkeepsie made in 1798 as Lewis's ferry. On an ancient map dated 1797, made from the surveys and field book of Dr. Benjamin Eley, by Henry Livingstone, of Poughkeepsie, for Stephen Nottingham, supervisor of the town of Marlborough, it is set down as Powell's dock and ferry. Jacob and Thomas Powell, who had a store and tavern, ran this ferry and also a line of sloops to New York city that carried the wood, produce, etc., for the farmers for a wide extent of country, and brought back their supplies. The Powells were here several years. Thomas Powell afterwards and about 1800 moved to Newburgh, became very successful and acquired a large fortune. The steamers, Thomas Powell and Mary Powell were named after him and his wife. It has been claimed that his first money was made here by the ferry and his other enterprises. At a later date Benjamin Townsend ran this ferry and carried on business. I can find no mention of it after about 1810, and presume it was then discontinued, as none of the oldest inhabitants of this neighborhood can remember this ferry, though they have heard about it from their parents and grandparents. A ferry had been established at Poughkeepsie about 1798, as appears by an advertisement of a ferry (1798) in the Poughkeepsie Journal. "N. B. The Ferryes is now established upon a regular plan, and travelers to the westward will find it much to their convenience to cross, the river at the above place as it shortens their journey, and they may be sure they will meet with no detention." By 1810 the Barnegat lime business had commenced to decline and emigration from Westchester county and Long Island has ceased, so a great part of the usefulness of the ferry had gone by 1810. People journeyed by means of this ferry from Massachusetts and Connecticut to New Jersey, Pennsylvania and the west. During the revolution, continental soldiers crossed here to and from the eastern states; specie, currency and provisions for the army were also carried. Washington with his body guard or attendants is supposed to have crossed on this ferry on one occasion. All the description of the boat or vessel used as the ferry, that we have, is that it was a rude scow or barge of some kind with sails and oars which ran most of the time on signals. It could carry teams, cattle and passengers; and it was said that at times horses were tied behind and swam over. It was said to have been the same kind of a boat as the boat then running at Troy. It must have been a strong boat, for it made trips in stormy weather, but not during the season when ice was on the river. The sides would be let down, and it was entered in this way. There is no tradition that there ever was an accident or loss of life by means of the ferry. To be sure there must have been different boats at different times as the old ones wore out, but the description of all was about the same. Very little, if any, shelter was provided and it was only temporary when it was. In heavy storms the vessel lay at its dock. The landing on the east side of the river must have been in the vicinity of Barnegat or at least it landed there a part of the time, for the ferry carried quantities of lime and lime rock to this side. This was one of the supports of the ferry. The lime business at Barnegat was commenced soon after the close of the revolution, and it is claimed lime was burned there during the war or even before as people used lime from somewhere before that time all about here and the surrounding country. At least soon after the war we had lime kilns on the west side and they must have been started soon after those at Barnegat, as there has never been lime rocks about here, and the rock was brought over and burned here. I find in our ancient records in the laying out of a road. "A return of an open public road as follows: We, the commissioners for the town of Marlborough, in the year 1790, in the month of June. By a petition from the freeholders and inhabitants of said town for a public road or highway from Latting Town to Hudson river, have laid it out as follows: *** [sic] Said road is to extend four rods down the hill from the upper side of the road as it now runs down to Lewis lime kiln: the said road to go either side of said Elijah Lewis's dwelling house wherever it shall be thought most convenient for the good of the publick, down to low water mark to extend four rods up and four rods down the river from the lime kiln. ***" [sic] The Powells also had lime kilns. Quimby, Anning Smith and others. The stones for these kilns came from Barnegat. By the map of Dr. Benjamin Eley and Henry Livingston, above referred to, there are designated on the map 20 limekilns at Barnegat. I cannot find that a company owned them. Barnegat had a store, a schoolhouse and a Church or else preaching was held in the schoolhouse. A Methodist exhorter from here held services there. ln an ancient Gazetteer of the state, I find as follows: "Marlborough, a small township in southeast corner of Ulster county. on the west shore of the Hudson, opposite Barnegat." There was maintained at one time an efficient company of militia. It was said that during navigation there was hardly a time that one or more sloops were not there loading lime: and at one time a line of sloops carried the lime rock from there to New Brunswick, New Jersey, to burn there. Tom Gill and his father burned lime there. One kiln was near their house. There is a tradition here about the Gills. It is that when Vaughn went up the river, a corporal and two of the men were sent ashore in a rowboat to burn the mill on the site of the present mill. The then owner begged them to spare the mill, and said to the corporal whose name turned out to be Gill, that if he would not burn the mill, he could come back and marry his daughter after the war, at the same time pointing out an attractive young girl. It appears that the corporal, to deceive the soldiers on the vessel, burned some old buildings about there, and many years afterward the old mill was torn down, and the present mill erected. The old mill, in the account given by General Clinton, is called Buren's mills. But this is wrong as I cannot find that Van Buren ever owned it, but it was owned by one Van Keueren. The old mill was spared, and the corporal afterward returned, married the girl and became the owner of the property. It is claimed to this day that he was the father of Tom Gill who died fifty or sixty years ago. There were two roads leading to Barnegat, one from a southerly direction and one from an easterly or northeasterly direction which were used as such years before any roads about there were regularly laid out. When a child I had heard old men about here telling of having worked at these kilns and crossing with the ferry when they were young. They received $1 a day which at that time was considered princely pay, and such work was then sought for; farm laborers then receiving 50 cents or less a day. Lime carried by this ferry was drawn and used not only in the towns of Marlborough and Plattekill. but in the towns of Paltz, Shawangunk and what is now Gardiner. Numerous houses all over these towns are still standing that were built with Barnegat lime. The tradition is that the lime was considered a very superior quality, but the rock was either worked out or a better article found elsewhere, as for many years no lime has been produced there. The roads on both sides of the river were used as highways at least fifty years before they were laid out and recorded by the highway commissioners. There is a tradition about another ferry which I can not reconcile. It is that in 1777 when Gen. Vaughn's expedition went up the river, Samuel Hallock, the old Quaker minister went out in a row boat to meet the fleet, and when taken on the flagship said to Vaughn that he was a non-combatant, a Quaker, and was opposed to the war, and at the same time pointed out to the General his ferry boat along the shore. Vaughn gave orders not to disturb the Quaker or his boat, and the vessel was saved. But Hallock may have had this ferry as this was in 1777, and we have seen that Lattimer had the ferry in 1779. It is possible that it may have been a boat used for some other purpose, but was always spoken of as a ferry boat in the traditions. Hallock at this time owned Brushes Landing, afterwards Sands Dock, and he most likely carried on business from there. At the dock from which the ferry ran there was an ancient stone house, almost a fort, as the walls were so thick and strong. It was made for a store, tavern, freight house, etc. It was torn down when the West Shore railroad took the land. There was quite a history and many traditions about this old house. There had previously been a house on the same site and other buildings about there, In March 1849, the Milton ferry was established by Captain Sears. It ran from just at the dock at Milton to the Gill dock. Sears ran the ferry for three years and then sold to Jacob Handley who conducted it until about 1862. The boat used had for its motive power four mules, who turned a tread wheel for the power. It run regularly and was a great convenience to the entire neighborhood, and for miles back in the country on this side. It was the regular route to Poughkeepsie, and to the Milton ferry, the station on the Hudson river road. It also carried the mails. At one time the Gills through whose lands the road leading from the ferry and the railroad station to the post road led, attempted to close it claiming it was a private road, but it was afterward arranged by them or the town authorities so that it was continued as a public road. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

0 Comments

As a boy I grew up in Port Ewen, a village south of Kingston. I remember the "Skillypot" as an almost square, rectangular-shaped, steam-driven chain ferry that ran on the Rondout Creek between Rondout (part of Kingston) and the hamlet of Sleightsburg. The ferry pulled herself back and forth across the creek on a chain which rolled up on a drum in her hold. Her formal name was "Riverside" but no one ever called her that. She was universally called the "Skillypot" (a Dutch derivative meaning "turtle") and a lot of other names as well, the kindest of which was "Otherside" by those who had just missed connections. The Skillypot was a relic of the foot passenger and horse and wagon era. She was placed in service in 1870 and ran without interruption, except for periodic maintenance and repairs, until 1922 when the present suspension bridge carrying Route 9-W over the Rondout Creek was opened to traffic. From the time automobiles came into general use until the Skillypot stopped running in Oct., 1922, she was a source of anger and frustration to those vacationing motorists who travelled northward on Route 9-W on holiday weekends and came to a halt somewhere south of the Rondout Creek in a growing line of autos waiting to cross on the ferry. Because the Skillypot could only carry about four cars, the backup was usually considerable and meant a long wait for most of those in line. There was a small iron bridge across the Rondout, upstream from Kingston, at a place called Eddyville. But few, if any, of the waiting drivers knew of this crossing. The situation was made to order for any enterprising boys of the area who worked the waiting line of autos offering to show their drivers a detour across the creek for a fee, usually a quarter or half-dollar. The procedure, when hired, was to ride the running board of the car and direct the drive "around the mountain" to Eddyville, over the bridge and back to the ferry slip in Rondout. The trip back to the ferry took the unsuspecting motorist a bit out of the way but it got the boy guide back to the ferry – which he then boarded, crossed to Sleightsburg for the two-cent passenger fare and started the procedure all over again. The Skillypot was unique and served a real purpose for a long time. But she didn't fit into the 20th century and when she finally stopped running I doubt if there were any who mourned her passing. AuthorWilliam E. Tinney's article was published in the Albany (NY) Times-Union on July 20, 1975 as part of the "I remember .." series. "Times-Union Editor's Note: Ten dollars will be paid for each I Remember published of the 1920s through 1950s." If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's note: The following is from the Kingston (NY) Daily Freeman, July 31, 1905, Thank you to Contributing Scholar George A. Thompson for finding, cataloging and transcribing this article. The language, spelling and grammar of the article reflects the time period when it was written. The Nautical Gazette says: One of the oldest pilots actively engaged in steamboating today is Captain James P. Ackley, who daily steers the Hudson River ferryboat "Brinkerhoff" on her trips between Poughkeepsie and Highland. Captain Ackley is 77 years of age, and has been in the boating business for sixty-five years. His first experience was on the sloop "Judge Swift", owned by the late Captain William Roberts. Following this he was pilot on some of the famous early-time Hudson river sloops, such as the "Westchester," "Deep River", "Alfred Richards" and others. Captain Ackley was first mate on the "Matthew Vassar" when that vessel made trips to Virginia for wood which was burned on the Hudson River rail-road instead of coal. The "Matthew Vassar" also made one trip to Bermuda during the Mexican war with a cargo of merchandise. This was Captain Ackley's last trip on her. Upon her return the gold excitement was at its height in California and the sloop was sold to a stock company of Poughkeepsians, who loaded her with a cargo of merchandise for the gold mines. This enterprise proved a failure financially. Captain Ackley was mate on the well known schooner "Oliver H. Booth". He was on her in Hampton Roads when Virginia seceded. When the crew heard the news all hands the crew heard the news all hands hastened to get out of their dangerous predicament. They took French leave, setting sail at midnight and finally got back to Poughkeepsie after several exciting adventures. The last interesting sloop of which Captain Ackley was master was the old "Surprise", owned by M, Vassar & Company. Her last cargo was in part the old cannon and cannon balls that now adorn the grounds around the soldiers' fountain, Poughkeepsie. The first steamboat Captain Ackley piloted was the "Fairfield", one of the original excursion boats to Coney Island, which made two trips a day from New York. It was the only boat running on this route at that time and had ample accommodations for all traffic. Just after the breaking out of the civil war Captain Ackley was pilot on the steamboat "H. S. Allison", which carried soldiers from Hart's Island to New York. From this boat Captain Ackley went with the Hudson river towing lines. They paid better wages than were offered on passenger boats. For nineteen years he was pilot on the largest towboats in the world, including the "Vanderbilt" and "Connecticut". He made a record in 1887 which has never been surpassed, that of towing 117 loaded boats in one tow from Albany to New York. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's note: The following are excerpts from NY Herald, September 7, 1857, p. 1, cols. 1-5 -- The New York Ferries. Thank you to Contributing Scholar George A. Thompson for finding, cataloging and transcribing this article. The language, spelling and grammar of the article reflects the time period when it was written. THE NEW YORK FERRIES. Visit of Inspection of One of the Herald Reporters to each Boat and Ferry Landing, and what he saw there -- Condition of Boats, and Means taken for Life Saving *** EAST RIVER. EIGHTY-SIXTH STREET OR HELL GATE FERRY. This ferry has but two boats, the Astoria, of 119 tons, built in 1840, and the Sunswick, of 129 tons, built in 1848. They are both built after the same primitive style of the Hoboken ferry boats. . . . *** Wednesday of every week this ferry is almost entirely converted into a cattle ferry, a large number crossing on almost every boat, which renders it anything but pleasant or agreeable for foot passengers. *** GREENPOINT, TENTH AND TWENTY-THIRD STREET FERRIES. THE TRIPS. The Tenth street ferry has two boats on from four o'clock in the morning until nine o'clock at night, so that one boat leaves the slip on either side of the river every ten minutes during those hours. From nine o';clock until quarter past one at night there is but one boat on, making twenty minute trips, after that hour, up to four o'clock in the morning, no boat runs. On the Twenty-third street ferry there is but one boat running from six o';clock in the morning up to ten o'clock at night, making fifteen minute trips. . . . THE LIGHTS. This company have set an example worthy of following by some of the other companies in respect to lighting their ferry slips, bridges and passenger ways at night, there being ten large gas lights inside of the ferry gates, two of them being at the end of each bridge. The boats all present a neat and clean appearance, the ladies cabins all being well cushioned. . . . *** Most of the business done by the ferry . . . is by the crossing of country wagons. . . . A very large number of funerals, also cross this ferry daily on their way to Calvary Cemetery. The foot passing over these ferries is as yet quite insignificant, owing in great measure to the fact that there is no shipbuilding or other mechanical business of any account going on at Greenpoint at present, and the fact that fever and ague abounds in the village of Greenpoint to a greater or less extent during the warm weather. HOUSTON STREET FERRY. *** The boats are usually kept in cleanly and comfortable condition, with the exception of lights in the cabins at night, which are very deficient, they being scarcely sufficient for passengers, sitting opposite each other to discern the precise complexion of their neighbor's countenance, much less to read by. . . . Two boats are kept running from five o'clock in the morning until ten o';clock at night. . . . After ten o'clock at night there is but one boat running until five in the morning. . . . *** PECK SLIP, DIVISION AVENUE AND GRAND STREET FERRIES. [Editor's Note: long discussion of the lack of accommodations] THE JAMES SLIP AND SOUTH TENTH STREET FERRY. [began running last May] The boats of this ferry are the "George Law", of 400 tons, one year old, and "George Washington", 400 tons, the same age, both of which are double decked, clean, commodious and well cushioned. *** The bridges on each side of the river are forty feet long, and thirty feet wide, on floats. The houses each have two fine sitting rooms for ladies and gentlemen, the seats in all of which are handsomely cushioned, the same as the ladies; cabins on the boats. *** The pilots employed on the boats of this company are quite too careless and reckless of human life. . . . *** UNION FERRY COMPANY. [Fulton Ferry: 4 boats; Wall street Ferry: 2 boats; Atlantic, or South street Ferry, 3 boats; Hamilton Avenue Ferry, 4 boats; Roosevelt street Ferry, 2 boats; Catherine street Ferry, 2 boats] *** South ferry run three boats every five minutes from 5 in the morning until 10 o'clock at night, and two up to 12 o';clock, after which there is one untill 5 in the morning. The Hamilton avenue ferry runs four boats during the day and one all night, as fast as they can be run. The Fulton ferry has four boats on all day and two on all night. The Catherine and Roosevelt street ferries have two boats on all day, and one all night at the Catherine ferry, and one on up to nine o'clock on the Roosevelt street ferry. The Wall street ferry has two boats on during the day, and one on from six in the evening until twelve at night, when both are drawn off until four o'clock in the morning. [a new boat is being built, that will have gas lights in the cabins] JERSEY CITY FERRY. *** [among the boats on this ferry is the] "John S. Darcy", built in 1857, tonnage 700, and one hundred horse poser engine. . . . This boat has just been put on the ferry, and is a perfect floating palace. She is lit up with gas, which is introduced in tanks . . . ; these tanks being filled and taken on board as often as necessary. *** Three boats are run on the Jersey city ferry from 4 o'clock in the morning until half-past 10 o'clock, making about ten minute trips. From half-past ten at night until four in the morning two boats are run, making half hour trips. THE HOBOKEN FERRIES. This ferry being the principal breathing outlet to the city, especially for women and children, who desire to take a sail during the warm weather, and the thousands who daily visit Hoboken, of all sexes and ages for pleasure, it is something to be regretted that the present owner of the several ferries, Edwin A. Stevens, Esq., does not take more active means to provide against any accident of emergency which is so liable to arise at any moment, especially on boats so continually crowded as those are with females and children. *** The following are the names and ages of the boats owned on these ferries: -- BARCLAY STREET FERRY James Watts, built in 1851, tonnage 312 31-95. Patterson, built in 1854; tonnage 360 62-95. CANAL STREET FERRY John Fitch, built in 1845, tonnage 125 75-95. CHRISTOPHER STREET FERRY Phoenix, registered in the custom house as Fairy Queen, built in 1826, and subsequently cut in two, and about 70 feet added to her middle. She is 141 81-95 tons burden. SPARE BOATS. Chancellor Livingston, built in 1852; tonnage 457 61-95. Newark, built in 1827; tonnage 175 17-95. Hoboken, built in 1822; tonnage 322 20-95 These boats are all built in the primitive style, with but one carriage way, and no separate passage for foot passengers. [their life boats] The John Fitch has a metallic life boat the proper length. The Hoboken, which issued on the Christopher street ferry as a cattle boat, is without any boat, corks, boat hooks, ladders, floats, or any conveniences whatever for saving life, with the exception of one old cork life preserver, hung on the upper deck. The boats on the Newark and Phoenix are miserable concerns and unfit for use. . . . Those on the other four boats are better, but not such as should be provided, with the single exception of the metallic boat. Each of the six boats, are otherwise supplied with from five to six cork buoys, only one of which on either boat is supplied with a lanyard, and one pike pole, all of which are kept tied to braces on the upper decks of the boat, and consequently would be of . . . little purpose . . . in the event of an unlooked for accident. . . . The Phoenix is said by those who should know to be unsafe, and entirely unfit for use as a ferry boat. *** The ferry bridges are for the most part swing bridges, the only suitable ferry house being that at the foot of Barclay street. On the Hoboken side carts and wagons are driven in every direction at hap hazard, inside of the gates promiscuously among the passengers, rendering it anything but agreeable or safe for foot passengers, especially during the busy portions of the day. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

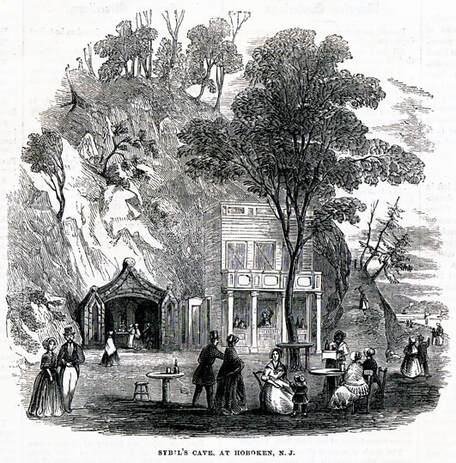

Editor's note: The following text is an except from "Fifteen Minutes around New York" by George G. Foster, published by DeWitt & Davenport, New York circa 1854, pages 52-54. Thank you to Contributing Scholar George A. Thompson for finding, cataloging and transcribing this article. The language, spelling and grammar of the article reflects the time period when it was written. It was very warm -- a sort of sultry, sticky day, which makes you feel as if you had washed yourself in molasses and water, and had found that the chambermaid had forgotten to give you a towel. The very rust on the hinges of the Park gate has melted and run down into the sockets, making them creak with a sort of ferruginous lubricity, as you feebly push them open. The hands on the City Hall clock droop, and look as if they would knock off work if they only had sufficient energy to get up a strike. The omnibus horses creep languidly along, and yet can't stand still when they are pulled up to take in or let out passengers -- the flies are so persevering, so bitter, so hungry. Let us go over to Hoboken, and get a mouthful of fresh air, a drink of cool water from the Sybil's spring, a good roll on the green grass of the Elysian Fields. Down we drop, through the hot, dusty, perspiring, choking streets -- pass the rancid "family groceries," which infect all this part of the city, and are nuisances of the first water -- and, after stumbling our way through a basket store, "piled mountains high," we at length find ourselves fairly on board the ferry boat, and panting with the freshness of the sea breeze, which even here in the slip, steals deliciously up from the bay, which, even here in the slip, steals deliciously up from the bay, tripping with white over the night-capped and lace-filled waves. Ding-dong! Now we are off! Hurry out to this further end of the boat, where you see everybody is crowding and rushing. Why? Why? Why, because you will be in Hoboken fully three seconds sooner than those unfortunate devils at the other end. Isn't that an object? Certainly. Push, therefore, elbow, tramp, and scramble! If you have corns, so, most likely, has your neighbor. At any rate, you can but try. No matter if your hat gets smashed, or one of the tails is torn off your coat. You get ahead. That's the idea -- that's the only thing worth living for. What's the use of going to Hoboken, unless you can get there sooner than anyone else? Hoboken wouldn't be Hoboken, if somebody else should arrive before you. Now -- jump! -- climb over the chain, and jump ashore. You are not more than ten feet from the wharf. You may not be able to make it -- but then again, you may; and it is at least worth the trial. Should you succeed, you will gain almost another whole second! and, if you fail, why, it is only a ducking -- doubtless they will fish you out. Certainly they don't allow people to get drowned. The Common Council, base as it is, would never permit that! Well! here we are at last, safe on the sands of a foreign shore. New Jersey extends her dry and arid bosom to receive us. What a long, disagreeable walk from the ferry, before you get anywhere. What an ugly expense of gullies and mud, by lumber yards and vacant lots, before we begin to enjoy the beauties of this lovely and charming Hoboken! One would almost think that these disagreeable objects were placed there on purpose to enhance the beauties to which they lead. At last we are in the shady walk -- cool and sequestered, notwithstanding that it is full of people. The venerable trees -- the very same beneath whose branches passed Hamilton and Burr to their fatal rendezvous -- the same that have listened to the whispering love-tales of so many generations of the young Dutch burghers and their frauleins -- cast a deep and almost solemn shade along this walk. We have passed so quickly from the city and its hubbub, that the charm of this delicious contrast is absolutely magical. What a motley crowd! Old and young, men women and children, those ever-recurring elements of life and movement. Well-dressed and badly-dressed, and scarcely dressed at all -- Germans, French, Italians, Americans, with here and there a mincing Londoner, with his cockney gait and trim whiskers. This walk in Hoboken is one of the most absolutely democratic places in the world -- the boulevards of social equality, where every rank, state, condition, existing in our country -- except, of course, the tip-top exclusives -- meet mingle, push and elbow their way along with sparse courtesy or civility. Now, we are on the smooth graveled walk -- the beautiful magnificent water terrace, whose rival does not exist in all the world. Here, for a mile and a half, the walk lies directly upon the river, winding in and out with its yielding outline, and around the base of precipitous rocky cliffs, crowned with lofty trees. From the Bay, and afar off through the Narrows, the fresh sea breeze comes rushing up from the Atlantic, strengthened and made more joyous, more elastic by its race of three thousand miles -- as youth grows stronger by activity. Before us, fading into a greyish distance, lies the city, low and murky, like a huge monster -- its domes and spires seeming but the scales and protuberances upon his body. One fancies that he can still hear the faint murmur of his perpetual roar. No -- 'tis but the voice of the pleasant waves, dashing themselves to pieces in silver spray, against the rocky shore. The retreating tide calls in whispers, its army of waves to flow to their home in the sea. Take care -- don't tumble off these high and unbalustraded steps, -- or will you choose rather to go through the turn-stile at the foot of the bluff? It is very lean, madam -- which you are not -- and we doubt if you can manage your way through. We thought so! Allow me to help you over the steps. They are placed here, we verily believe, as a practical illustration of life -- up one side of the hill, and down the other -- for there is no material, physical, or topographical reason, that we can discover, for their existence. Here is a family group, seated on the little wooden bench, placed under this jutting rock. The mother's attention is painfully divided equally between the two large boys, the toddling little girl of six, who laughs and claps her hand with glee at discovering that she can't throw a pebble into the water, like her brothers -- and the baby, who spreads out his hands and legs to their utmost stretch, like the sails of a little boat which tries to catch as much of the breeze as it can, and who crows like a little chanticleer, in the very exuberance of his baby existence. Two half nibbled cakes, neglected in the happiness of breathing this pure, keen air -- which, by the way, will give them a tremendous appetite, by-and-by -- are lying among the pebbles, and ever the baby has forgotten to suck its fat little thumb.  Sybil’s Cave is the oldest manmade structure in Hoboken, created in 1832 by the Stevens Family as a folly on their property that contained a natural spring. By the mid-19th century the cave was a recreational destination within walking distance from downtown Hoboken. A restaurant offered outdoor refreshments beside the cave. https://www.hobokenmuseum.org/explore-hoboken/historic-highlights/sybils-cave/sybils-cave-today-and-yesterday/ The Sybil's Cave, with its cool fountain bubbling and sparkling forever in the subterranean darkness, now tempts us to another pause. The little refreshment shop under the trees looks like an ice-cream plaster stuck against the rocks. Nobody wants "refreshments," my dear girl, while the pure cool water of the Sybil's fountain can be had for nothing. What? Yes they do. The insane idea that to buy something away from home -- to eat or drink -- is at work even here. A little man, with thin bandy legs, whose bouncing wife and children are a practical illustration of the one-sided effects of matrimony, has bought "something to take" for the whole family. Pop goes the weasel! What is it? Sarsaparilla -- pooh! Now let us go on round this sharp curve, (what a splendid spot for a railroad accident!) and then along the widened terrace path, until it loses itself in a green and spacious lawn, lovingly rising to meet the stooping branches of the trees. This is the entrance to the far-famed Elysian Fields. Along the banks of the winding gravel paths, children are playing, with their floating locks streaming in the wind -- while prone on the green grass recline weary people, escaped from the week's ceaseless toil, and subsiding joyfully into an hour of rest -- to them the highest happiness. The centre of the lawn has been marked out into a magnificent ball ground, and two parties of rollicking, joyous young men are engaged in that excellent and health-imparting sport, base ball. They are without hats, coats or waistcoats, and their well-knit forms, and elastic movements, as they bound after the bounding ball, .... Yonder in the corner by that thick clump of trees, is the merry go-round, with its cargo of half-laughing, half-shrieking juvenile humanity, swinging up and down like a vessel riding at anchor. Happy, thoughtless voyagers! Although your baby bark moves up and down, and round and round, yet you fell the exhilarating motion, and you think you advance. After all, perhaps it would be a blessed thing if your bright and happy lives could stop here. Never again will you bee so happy as now; and often, in the hard and bitter journey of life, you will look back to these infantile hours, wondering if the evening of life shall be as peaceful as its morning. But the sun has swung down behind the Weehawken Heights, and the trees cast their long shadows over lawn and river, pointing with waving fingers our way home. The heart is calmer, the head clearer, the blood cooler, for this delicious respite. We thank thee, oh grand Hoboken, for thy shade, and fresh foliage, and tender grass, and the murmuring of the glad and breezy waters -- and especially for having furnished us with a subject for this chapter. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

The Claire K. Tholl Hudson River collection of Hudson River Maritime Museum has just been added to the New York Heritage website. Thank you to volunteer Joan Mayer for her work digitizing these images. See all of the Hudson River Maritime Museum collections here: Claire K. Tholl (1926-1995) was an architectural historian, cartographer and naval engineering draftsman. Born in Hackensack, New Jersey Claire Koch Tholl studied engineering and naval designing at Stevens Institute of Technology from Cooper Union in 1947. She worked as a draftsman during World War 2 at Pensacola Naval Air Station, Florida. She moved into historic preservation and architectural history and over her career worked to preserve more than 200 stone houses in New Jersey. She was an early member of the Steamship Historical Society of America and retained her love of steamboats. The collection includes postcards and photographs of steamboats, ships and ferries. Hudson River Maritime Museum is able to contribute to New York Heritage thanks to the work of the Southeastern Regional Library Council. New York Heritage enables the museum to share a sample of the thousands of Hudson River images in the museum's collection with viewers around the world. About New York Heritage: New York Heritage Digital Collections features a broad range of materials that present a glimpse into our state’s history and culture. Over 350 libraries, museums, archives, and other cultural institutions make their collections available in our repository. These primary source materials span the range of New York State’s history, from the colonial era to present. Our stories are told through photographs, letters, diaries, directories, maps, books, and more. New York Heritage is a collaborative project of eight of the nine Empire State Library Network library councils: Capital District Library Council, Central New York Library Resources Council, Long Island Library Resources Council, Northern New York Library Network, Rochester Regional Library Council, Southeastern New York Library Resources Council, South Central Regional Library Council, and Western New York Library Resources Council. Take a historical tour of New York State here. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Film still from the 1911 Svenska Biografteatern film of New York City, featuring a tugboat and barge at far left, passenger ferry in the middle distance, and another tugboat (stack smoking) towing a barge at right. The Brooklyn Bridge is in the background and the Manhattan Bridge is in the foreground. A few years ago the Metropolitan Museum of Art release this beautifully shot film of New York City in 1911. Made by a team of cameramen with the Swedish company Svenska Biografteatern, these views of New York were just one of the films they made chronicling famous cities around the world. Some of this footage may look familiar, as you may have seen a shorter version (basically they cut the steamboats out!) published in 4K on YouTube a few years ago that went viral. A genealogist even did a follow-up investigation of some of the people featured in the film, and tracked down their ancestors! But for the maritime historians at HRMM, the version published by MOMA was super fun to watch because we got to see several historic steamboats in action! The Orient, Mary Patten, Rosedale, and the sidewheel steam ferry Wyoming are all featured, and the Rosedale and the Wyoming are both depicted underway with their walking beam steam engines rocking away. It's interesting to see how slowly the walking beam is moving when compared to the speed of the boats, which indicates that those pistons are moving with an incredible amount of force to turn the paddlewheels so quickly. Although the rest of the film is fun to watch, the steamboats are in the first two minutes, so we thought we'd give a little history of some of the vessels you're seeing! The sidewheel steamboat Orient was originally built in 1896 as the Hingham for the Boston & Hingham Steamboat Company. In 1902 she was purchased by the Montauk Steamboat Company and renamed Orient, where she operated until 1921 when she was sold to a company in Mobile, Alabama and renamed Bay Queen and continued to operate until 1928. Built in 1893 in Brooklyn, NY the Mary Patten was operated by the Patten Steamboat Company, running between New York City and Long Branch, NJ, which was a resort area in the late 19th century. The Patten Line (also known as the New York and Long Branch Steamboat Company) was founded by Thomas G. Patten in 1890 and in 1893 he built a new passenger steamboat named the Mary Patten after mother, Maria (Mary) Patten, who had died in 1886. (It is not, sadly, named after heroic Cape Horner Mary Ann Brown Patten.) The steamboat Mary Patten stayed in the family and on the NYC run until 1930, when the Patten Line folded and the Mary Patten was sold to the Highlands, Long Branch, and Bred Bank Steamboat Company, where she may have operated for a year until being taken out of operation. The history of the sidewheel steam ferry Wyoming was not easy to track down, especially since there were a number of other vessels named Wyoming, including an earlier sidewheel steamboat immortalized by James Bard. But thankfully Brian J. Cudahy's Over and Back: The History of Ferryboats in New York Harbor had some answers. The iron-hulled, walking beam sidewheel steam ferry Wyoming was built in 1885 by Harlan & Hollingsworth in Wilmington, Delaware for the Greenpoint Ferry Company (1853-1921). The Wyoming was in service as a ferry on the East River until around 1920, when she was sold to the City of New York. She "later ran for upper Hudson River interests" (p. 444 of Cudahy) until she was scrapped in 1943, likely a victim of both bridges and the war effort. The above photo, taken in 1940 by steamboat historian Donald C. Ringwald, may have been one of her last. If you'd like to learn about the last steamboat visible in the film above, the Rosedale, stay tuned! We'll featured more on her later this week. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor’s Note: The following text is a verbatim transcription of an article featuring stories by Captain William O. Benson (1911-1986). Beginning in 1971, Benson, a retired tugboat captain, reminisced about his 40 years on the Hudson River in a regular column for the Kingston (NY) Freeman’s Sunday Tempo magazine. Captain Benson's articles were compiled and transcribed by HRMM volunteer Carl Mayer. See more of Captain Benson’s articles here. This article was originally published May 21, 1972. On Saturday, May 19, 1928, in the early afternoon of a beautiful spring day, a collision occurred off Rondout Lighthouse between the ferryboat “Transport” and the steamer “Benjamin B. Odell” of the Central Hudson Line. At the time, I was deckhand on the steamer “Albany” of the Hudson River Day Line, helping to get her ready for the new season after her winter lay up at the Sunflower Dock at Sleightsburgh. On Saturdays, we knocked off work at 11:30 a.m. As I rowed up the creek in my rowboat to go home, the big “Odell” was still at her dock at the foot of Hasbrouck Avenue at Rondout. At 12:25 p.m. the “Odell” blew the customary three long melodious blasts on her big whistle, high on her stack, as the signal she was ready to depart. At home, eating lunch, I heard her blow one short blast promptly at 12:30 p.m. as the signal to cast off her stern line. From the Porch Following a habit of mine from a young boy, I went out on our front porch to watch her glide down the creek at a very slow pace past the Cornell shops, Donovan’s and Feeney’s boat yards, and the freshly painter [sic] “Albany.” The “Odell” looked to me like a great white bird slowly passing down the creek. At the time, I thought how in less than two weeks we would probably pass her on the “Albany” on the lower Hudson on Decoration Day, both steamers loaded with happy excursionists on the first big holiday of the new season. As the “Odell” passed Gill’s dock at Ponckhockie, I went back in the house to finish lunch. A few minutes later I heard the “Odell” blow one blast on her whistle, which was answered by the “Transport” on her way over to Rhinecliff, indicating a port to port passing. Hearing steam whistles so often in the long ago day along Rondout Creek was something one took for granted, assuming they would be heard forever. Then I heard the danger signal on the whistle of the “Transport” followed by three short blasts from the “Odell’s” whistle, indicating her engine was going full speed astern. Shortly thereafter, I could hear the “Transport” blowing the five whistle signal of the Cornell Steamboat Company of 2 short, 2 short, 1 short, meaning we need help immediately. I ran down to my rowboat tied up at the old Baisden shipyard, and looked down the creek. I could see the “Transport” limping in the creek very slowly, her bow down in the water, and her whistle blowing continuously for help. I also noticed several automobiles on her deck. Looking over the old D. & H. canal boats that were deteriorating on the Sleightsburgh flats, I could see the top of the “Odell” stopped out in the river. After a few minutes, she slowly got underway and proceeded on down the river, her big black stack belching smoke, so I figured she was not hurt. Decision to Beach As the “Transport” approached the Cornell coal pocket, her captain, Rol Saulpaugh, decided to beach her on the Sleightsburgh shore. Nelson Sleight, a member of her crew, asked me to run a line over to the dock a the shipyard in the event she started to slide off the bank. I took the line and ran it from where the “Transport” grounded to the dock. In the meantime, the Cornell tugboat “Rob” came down the creek, from where she had been lying at the rear of the Cornell office at the foot of Broadway, and pushed the ferry a little higher on the bank. After taking the line ashore, I went back and asked if there was anything else I could do. Captain Saulpaugh asked me if I would row up to the ferry slip and get Joseph Butler, the ferry superintendent, and bring him over to the “Transport,” which I did. On the way over, Butler told me he had already called the Poughkeepsie and Highland Ferry Company to see if he could get one of its ferries to run in the “Transport’s” place. The afternoon about 5 p.m., the Poughkeepsie ferryboat “Brinckerhoff” arrived in the creek and began running on the Rhinecliff route. When we got back to the “Transport,” mattresses and blankets had been stuffed in the hole the “Odell” had slicked in the over-hanging guard and part of the hull. When she was patched, the “Transport,” with the “Rob’s” help, backed off the mud and entered the Roundout slip stern first - and the cars on deck were backed off. Then, the “Rob” assisted the ferry to make her way up to the C. Hiltebrandt shipyard at Connelley for repairs. There she was placed in drydock, the damage repaired, and in a week she was back in service on her old run. A Flood Tide The cause of the mishap at the mouth of the creek was a combination of a strong flood tide, a south wind and a large tow. Out in the river, the big tugboat “Osceola” of the Cornell Steamboat Company was headed down river with a large tow. She had just come down the East Kingston channel and at that moment was directly off the Rondout Lighthouse. When there is a strong flood tide, there is a very strong eddy at the mouth of the creek. The tide, helped by a south wind, sets up strong and when it hits the south dike, it forms a half moon about 75-100 feet out from the south dike and then starts to set down. As the “Odell” was leaving the creek and entering the river, the “Transport” was passing ahead of the tow, around the bow of the “Osceola.” The “Transport” probably hit the eddy caused by the flood tide. In any event, she didn’t answer her right rudder and took a dive right into the path of the “Odell.” The “Odell” couldn’t stop in time and cut into the forward end of the ferry about 6 or 8 feet. No one was hurt and there was no confusion on either boat. The “transport” bore the brunt of the bout; the only damage to the “Odell” being some scratched paint on her bow. I heard later from the Dan McDonald, pilot on the “Osceola,” that there would be the lawsuit as a result of the collision - and he had been served with a subpoena to appear as a witness. He never had to appear, however, as Captain Greenwood of the “Odell” later told me the case was settled out of court. The next year the Central Hudson Line, because of the inroads made by the automobile, went out of business. The “Benjamin B. Odell”, however, continued to run on the river for another company until February 1937 when she was destroyed by fire in winter lay up at Marlboro. The “Transport” continued running on the Rhinecliff ferry route until September 1938 when she was withdrawn from service. She was later cut down and made into a stake boat for the Cornell Steamship Company for use in New York harbor. AuthorCaptain William Odell Benson was a life-long resident of Sleightsburgh, N.Y., where he was born on March 17, 1911, the son of the late Albert and Ida Olson Benson. He served as captain of Callanan Company tugs including Peter Callanan, and Callanan No. 1 and was an early member of the Hudson River Maritime Museum. He retained, and shared, lifelong memories of incidents and anecdotes along the Hudson River. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

The Pier at Piermont extends almost a mile out into the Hudson River. This image may have been taken shortly after World War II. The ferry slip is in place and to its left are two abandoned barges. There is a dock for boats at the very end. Street lamps and power poles stick up above the roadway and vegetation. In the background is the Village of Piermont. Courtesy Nyack Library Local History Room. Piermont, NY was once the terminus of the longest railroad in the world - the Erie Railroad. Hampered by rules about railroads crossing state lines, the Erie RR built a pier nearly a mile long across the marshy bay at Piermont and out to the deeper parts of the Hudson River, where steamboats could pick up passengers and take them on to New York City. To learn more about the fascinating history of the pier, check out this short video produced by the Lamont Doherty Earth Observatory, whose Hudson River Field Station is located in Piermont. You can learn more about the history of Piermont Pier, especially its role in World War II from the Piermont Historical Society. Some of the older portions of the pier were also historical hazards, as the Tugboat "Osceola" found out in 1903. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Today's Media Monday is a great story about being stranded on the Newburgh Beacon Ferry! When the weather gets colder, most boat traffic on the Hudson River ceases, except for commercial traffic in the shipping channel, which today is kept open by Coast Guard icebreakers.

Most historic boat traffic on the Hudson River was seasonal, too, mostly because the Coast Guard icebreakers are a 20th century invention. Because they traveled the same space frequently, most ferries tried to stay in service as long as possible in the days before bridges, and they were often the last vessels on the river each year. But it didn't always work out so well! Listen below for the full tale.

Brief summary: In the early 1950's, the Ferry got stuck in the ice on its 11:30 PM return trip to Beacon. Betty Carey remembers the story of one passenger who was stranded on the boat until rescued the next morning.

Have you ever gotten stranded because of snow or ice?

If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

|

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 [email protected] Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |