History Blog

|

|

|

|

|

This barrel piano is a more recent addition to the museum's collection and is believed to have been used to provide music for the Merry-Go-Round or carousel at Kingston Point Park. A barrel piano, also known as a street piano, uses a hand crank to turn a pinned barrel. The pins in the barrel hit the levers of the piano hammers, which then strike the piano strings, making a sound. How the pins are placed on the barrel determines what song is played. The person operating the crank must move it in a steady rhythm, or the music will come out jumbled. Sometimes confused with other crank instruments like the barrel organ (which uses forced air and pipes to make sound) or the hurdy gurdy (which turns a rosined wheel against the strings of a violin-like instrument), the barrel piano was often a feature of amusement parks. Also not to be confused with the steam calliope, which would have provided music aboard steamboats and was powered by their steam engines. The museum's particular barrel piano, also known as a cylinder piano, was manufactured by E. Bona & A. Atoniazzi in New York City. Little is known about the original owners, but the company became known later as the B.A.B. Organ Company. You can read more about the company history here. To hear what a barrel piano might have sounded like, check out this video of one playing a very complex piece of music. If you would like to see the barrel piano in person, come visit the Hudson River Maritime Museum and head to the East Gallery.

0 Comments

Editor’s Note: Welcome to the next episode in our 11-part account of Muddy Paddle's narrowboat trip through the Erie Canal and the Cayuga & Seneca Canal in western New York. The New York State Barge Canal system is in many ways a tributary of the Hudson River. It still connects the Great Lakes, the Finger Lakes, and Lake Champlain with the Atlantic Ocean by way of the Hudson River. Our contributing writer, Muddy Paddle, shares his experiences aboard the "Belle Mule." All the included illustrations are from his trip journal and sketchbooks. Day 4 - TuesdayLast night I paid our bill at the marina and told Captain Terry that I was planning to depart early in the morning by making a tricky three-point turn with the Belle. He didn’t like that plan at all, and later confided to the first mate that the Belle’s captain was “loco.” Brent tried to calm him down but It bothered him enough that when we woke up Tuesday morning, we found that the captain had relocated the big cruiser at our stern giving the Belle a clear exit to the gap in the breakwater. We shoved off under the good captain’s wary eye at 8:15 and shaped our course north along the east shore of the lake. We were hoping to get a nice view of Hector Falls, but we were in too close to the shore, and the falls were completely screened by topography and vegetation. We had a pleasant cruise down the lake with a gentle breeze at our back. As we reached Lodi Point, Brent fired up the gas grill and prepared barbecue pork chops for lunch. Brent loves to cook! The view from the helm consisted of the American flag at our mast, clouds of smoke rising from the bow, and intermittent appearances of our broadly grinning first mate, Brent. There were no boats out on the lake at all. It occurred to me that if we had mechanical trouble or worse, no help was readily available and that there were few access points given the steep banks rising up from the lake. It also occurred to someone on shore that our boat was on fire. A call was apparently made to one of the fine local fire departments. A couple of trucks appeared on the ridge to our east but returned to the station after apparently using binoculars or smelling our pork chops. We reached Geneva after lunch and it grew overcast as we re-entered the C&S Canal. Here we encountered kayakers and a replica of the steam launch African Queen. Brent radioed Lock 4 when we saw the Waterloo water tower. The lock came up abruptly around a sharp bend in the canal. There was a heavy outflowing current bent on carrying us to the adjacent spillway where a rental company canalboat was stuck with emergency lines holding her in place. A breeze from the west didn’t help. We bumped our way into the lock chamber, crooked but safe. We were very grateful to have missed the rendezvous with the other boat and the spillway and even more grateful when the lock doors closed, blocking the breeze. Once again I was unable to keep the engine in neutral. The transmission would creep forward and then backward requiring constant adjustments. I tried using a boat hook to handle the hand line nearest the stern without leaving the pedestal, but once the boat gained any momentum, it was impossible. Brent held tight to his line in the bow, so the stern was always the first to go rogue. Once through the lock, we had a routine return to Seneca Falls and tied the boat up to the wall near the Heritage Area Center. The stranded canal boat was recovered from the edge of the spillway later in the afternoon and towed with her frightened occupants to the wall next to us. The renters were sputtering about the boat, the rental company and their “near death” experience at the spillway. They ended their trip in a rented Escalade after abandoning all of their provisions and all of their pride at our gangway. After cleaning, putting away the new food and making the Belle shipshape, we took ourselves on a walking tour of Seneca Falls. At Seneca Falls, a series of waterfalls and rapids created a barrier for west-bound travelers on the Seneca River. A portage was established in 1787 and mills took advantage of water power early in the 19th century. The Seneca & Cayuga Canal established locks here in 1818 and the connection between the two lakes and the Erie Canal was completed in 1825. Using abundant water power and the ability to ship materials by canal, Seneca Falls became a thriving mill town of four and five story mill buildings, foundries, housing, churches and stores employing thousands of laborers. It was against this background that Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Mary Ann McClintock and others organized the Women’s Rights Convention in 1848 at the Wesleyan Chapel on Fall Street. Central New York and the “burned over district” were primed for reform and advocates for abolition, women’s rights and Native Peoples’ rights had been recruiting in the area, especially among a branch of the local Quaker community. The convention, housed within a plain brick church, attracted both women and men and luminaries including Lucretia Mott and Frederick Douglass. It resulted in the publication of the Declaration of Sentiments, now recognized as a seminal moment in the history of human rights. The chapel building became many things after the Convention including, ironically, its final degradation as a decrepit laundromat. To interpret the building’s history after acquisition, the National Park Service initially deconstructed it to reveal only those materials that were original to it in 1848, leaving large sections of the top and sides open to the elements and accelerated deterioration. In 2010, the building was sensibly enclosed with new material where necessary in order to preserve the original walls and the surviving roof timbers. We toured Fall Street, looked at the stores and restaurants, walked over to Elizabeth Candy Stanton’s house and finally sat to rest at a canal-side pavilion near Trinity Church. Lou, the boat owner’s representative, found us and gave us the unexpected but good news that the that the entire canal system would reopen tomorrow morning at 7:00 AM. We picked up a few supplies and had dinner at a pub on Fall St. It was dark when we returned to the boat. Lou staggered by for a visit after apparently spending a good part of the day at the American Legion. He stumbled on his way down the companionway steps and crashed flat on his face in the galley, blood trickling from his nose and mouth. We got him cleaned up and made him a cup of coffee before sending him home. We took power showers at the visitor center, checked our lines, and then called it a night. We will be entering the Erie Canal tomorrow! AuthorMuddy Paddle grew up near the junction of the Hudson River and the Erie Canal. His deep interest in the canal goes back to childhood when a very elderly babysitter regaled him with stories about her childhood on the canal in the 1890s. Muddy spent his college years on the canal and spent many of his working years in a factory building overlooking the canal. Over the years he has traveled much of the canal system by boat and by bicycle. Muddy Paddle's Erie Canal adventure will return next Friday! To read other adventures by Muddy Paddle, see: Muddy Paddle: Able Seaman, about Muddy Paddle's adventures on the replica Half Moon, and Muddy Paddle's Excellent Adventure on the Hudson, about his canoe trip down the Hudson River.

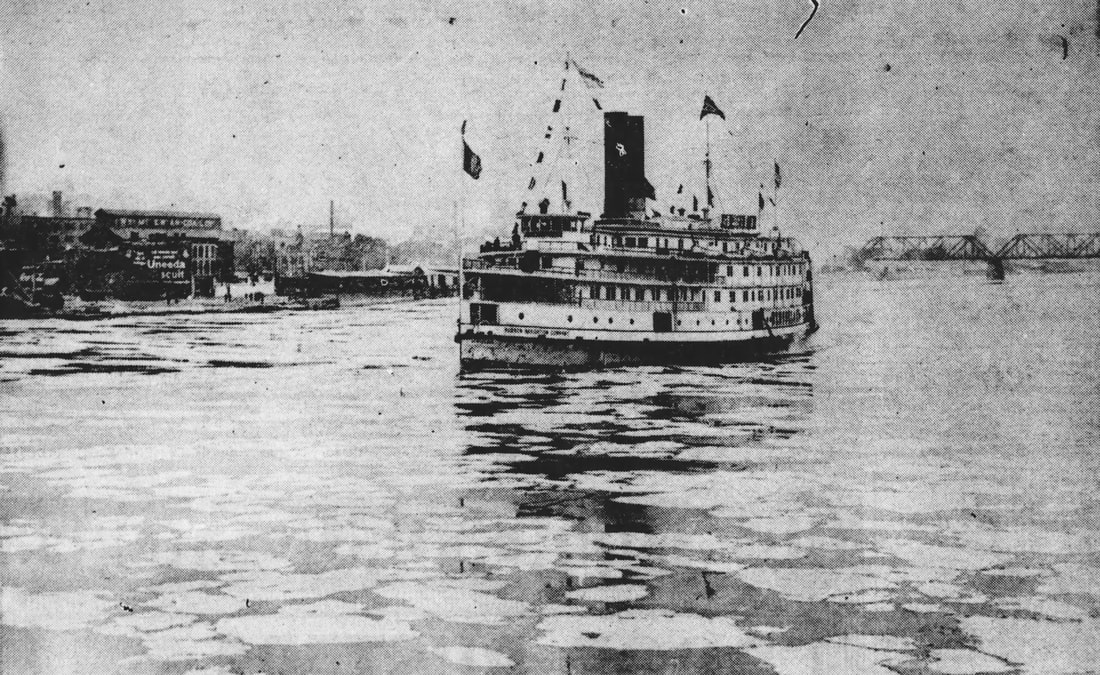

The History Blog is supported by museum members and readers like you! Donate or join today! Editor’s Note: The following text is a verbatim transcription of an article featuring stories by Captain William O. Benson (1911-1986). Beginning in 1971, Benson, a retired tugboat captain, reminisced about his 40 years on the Hudson River in a regular column for the Kingston (NY) Freeman’s Sunday Tempo magazine. Captain Benson's articles were compiled and transcribed by HRMM volunteer Carl Mayer. See more of Captain Benson’s articles here. This article was originally published February 18, 1973.  "THE STEAMBOAT “RENSSELAER” PASSES ALBANY on Jan. 29, 1913, the date of her mid-winter excursion. Although her flags and pennants are flying in mid-summer fashion, the floating ice in the Hudson and the very few people in deck testify to the frigid temperatures." Image originally published with article, February 18, 1973. In days gone by, steamboat excursions were commonplace. Almost without exception, they were offered during the summer and occasionally in the late spring or early autumn. One highly unusual excursion - probably the only one of its type - took place in the dead of winter on Sunday, Jan. 29, 1913. On that winter’s Sunday, the steamboat “Rensselaer” of the Hudson Navigation Company was chartered for an excursion by the Troy Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks, No. 141. From Troy down the river to Hudson and return. The story of that long ago excursion was related to me by the late Francis “Dick” Chapman of New Baltimore, one of the pilots of the “Rensselaer” the day of that wintry sail on the river. Dick said the sky was overcast, and it was a day when the cold “would penetrate right to your bones.” About 10 a.m. it started to snow and the river was full of floating cakes of ice. They were scheduled to leave Troy at 12:30 p.m. On the way down river, they were held up briefly at the first railroad drawbridge by a crossing freight train. When the bridge opened and the “Rensselaer” got in the draw, she lay there until the Maiden Lane Bridge, downstream, opened. She eventually passed the Night Line dock at Albany at 1:45 p.m. Down at Van Wies Point, below Albany, the river was covered with ice from shore to shore and the “Rensselaer” had to make a new channel. As she was going through the ice her paddle wheels would throw the ice up against the steel lining of her wheel batteries. It sounded like crashing thunder. One could hear the noise all through the streamer. Although they were originally scheduled to go down river as far as Hudson, Dick told me the visibility was so poor and the ice so heavy, they decided to go only as far as Castleton. There, they turned around and went back up river to Troy. They steamed slowly on the return so as to give the Elks their full time afloat. Since the visibility left much to be desired, it was somewhat questionable if the excursionists would have been able to see any more of the river if they had gone all the way on to Hudson. A few years later, the Night Line decided to try and operate year round service. The “Rensselaer” and her sister steamer “Trojan” were chosen for the operation. On one of the “Rensselaer’s” trips down river, she was passing a Cornell tow fast in the ice off Germantown. When the “Rensselaer” tried to pull out of the tracker and break into the solid ice to pass the tow, she sheared off right into the tow. The Cornell helper tug “George W. Pratt” - laying alongside the tow - couldn’t get out of the way and the guard of the “Rensselaer,” before they could get her stopped, went over the rail of the “Pratt” and shifted and damaged her deck house. With damages like that to the “Pratt,” and - after every trip - having to make repairs to the paddle wheel buckets and required to put new bushings in the arms of the feathering paddle wheels, the Night Line soon found the project to be too costly. Side wheel steamboats were just impractical for operation in the ice. During that short period when the “Rensselaer” and “Trojan” attempted to operate during the winter, old boatmen told me on a clear, cold night they could hear the “Rensselaer” or “Trojan” at Port Ewen when the steamers were up around Barrytown or on the up trip, as far away as Esopus Island. They would hear their paddle wheel pounding and breaking the ice and crashing the broken ice cakes against the steel paddle wheel housings. The captains and pilots of the night steamers on the river deserved a tremendous amount of credit for their skill in operating those old side wheelers in all kinds of weather. Unlike the captains and pilots of the day steamers that usually operated during the daylight in the best months of the year, the night boats would run from early spring to late fall and encounter lots of fog, snow or whatever came their way. The upper end of the Hudson in particular is very narrow, and the night boat men always had tows, yachts, and floating derricks and dredges to content with. Regardless of the weather, almost always they would bring their big steamboats into Albany on time. Those captains and pilots were, as they say, “right on the button.” The “Rensselaer” and the “Trojan” were cases in point. From the time they entered service in 1909 until the end of their service in the latter 1930’s, they rarely had a mishap. Probably the most serious mishap to the “Rensselaer” occurred on Sept. 27, 1833 when she was in a collision with an ocean freighter off Poughkeepsie. This incident will be the subject of a later article. AuthorCaptain William Odell Benson was a life-long resident of Sleightsburgh, N.Y., where he was born on March 17, 1911, the son of the late Albert and Ida Olson Benson. He served as captain of Callanan Company tugs including Peter Callanan, and Callanan No. 1 and was an early member of the Hudson River Maritime Museum. He retained, and shared, lifelong memories of incidents and anecdotes along the Hudson River. Need a break from the snow and cold? Take a virtual tour of the Hudson River in 1949! Featuring the historic Hudson River steamboat Robert Fulton, this 1949 film by the The Reorientation Branch Office of the Undersecretary Department of the Army, discusses the reorganization of the Hudson River Day Line Company briefly, before diving into a film version of what a trip up the Hudson would have looked like at that time. Lots of beautiful shots of the boats themselves as well as the Hudson River Day Line Pier in Manhattan. Sights seen include the New York skyline, George Washington Bridge, Palisades, the Ghost Fleet, a visit to Bear Mountain State Park, Sugar Loaf Mountain, West Point, Storm King Mountain, Bannerman's Island, Newburgh, Poughkeepsie, taking the bus to FDR's home in Hyde Park, Sunnyside, and back again. The Robert Fulton was built in 1909 in Camden, New Jersey by the New York Shipbuilding Co. for Hudson River Day Line. It operated from 1909-1954. In 1956 it was sold for conversion to a community center in the Bahamas. Many thanks to the Town of Clinton Historical Society for sharing this wonderful film. Editor’s Note: Welcome to the next episode in our 11-part account of Muddy Paddle's narrowboat trip through the Erie Canal and the Cayuga & Seneca Canal in western New York. The New York State Barge Canal system is in many ways a tributary of the Hudson River. It still connects the Great Lakes, the Finger Lakes, and Lake Champlain with the Atlantic Ocean by way of the Hudson River. Our contributing writer, Muddy Paddle, shares his experiences aboard the "Belle Mule." All the included illustrations are from his trip journal and sketchbooks. Day 3 - MondayNineteenth century photographs of Seneca Lake often echo similar scenes along the Hudson River. The long lake is surrounded by steep hills and its assortment of steamboats and canalboats look pretty familiar. The lake was also studded by large villas reminiscent of those on the Hudson and lakeside resorts. Commerce on the lake included the movement of coal and agricultural produce north to the Erie Canal and passenger steamers and ferries transited and criss-crossed the lake much as they did along the Hudson. I got up earlier than my mates and walked around the harbor at sunrise. There were a number of interesting and classic boats here including the excursion boat Seneca Legacy, the 1934 excursion boat Stroller, John Alden’s 1926 schooner Malabar VII and General Patton’s 1939 schooner When & If. I sketched vignettes of each and walked the shoreline in search of a souvenir. I recovered the neck of a green nineteenth century beer or soda bottle from a heap of dredge spoil as a talisman of Watkins Glen’s commercial past. Brent and I prepared bacon, eggs and toast in the galley and got caught on video doing a happy dance in front of the range. After cleaning up, we prepared picnic lunches, strapped on backpacks, and hiked to Watkins Glen State Park, about a mile south of the village. The park is one of the gems of the New York State park system and receives guests from around the world, many of them on tour buses heading to or from Niagara Falls. We encountered visitors from China, India and the Philippines. The centerpiece of the park is a two-mile gorge with 19 waterfalls and a precarious trail built on ledges, over stone bridges, through tunnels and up an endless series of steps and staircases. The park was established by a journalist in 1863 and acquired by New York State in 1935. A biblical flood in 1935 raised the water 80 feet deep midway through the gorge and within a few feet of a surviving bridge. Most of the stone-lined trail and bridges post-date this appalling flood.  The gorge at Watkins Glen. The gorge at Watkins Glen. We reached the top of the gorge and had a pleasant picnic under the shade of a tree. It was 88 F. It was easier descending the gorge than climbing it, but it was a hot afternoon so we stopped for ice cream at the “Colonial” on Main Street. We returned to the boat and relaxed for about an hour. We bought some wine on Main Street for friends and had dinner at an Italian restaurant a few blocks south of the lake. Overhearing the conversations, it was apparent that many of the diners here were connected with auto racing and the Gand Prix in particular. After dinner we saw a micro-beer ad at the Chamber of Commerce. Shauna was determined to get some for our son but it was only sold in growlers at the brewery or at a liquor store south of the state park entrance. The brewery was closed so she took one of the bikes lashed to the cabin top and rode into the sunset. She arrived just after the store closed but somehow convinced an employee to let her in to purchase the beer anyway. She returned triumphantly an hour later with a bulging backpack! We watched a comedy in the salon and enjoyed popcorn and chocolate. We called it a night at 11:00 PM and slept soundly on a calm and mild night. AuthorMuddy Paddle grew up near the junction of the Hudson River and the Erie Canal. His deep interest in the canal goes back to childhood when a very elderly babysitter regaled him with stories about her childhood on the canal in the 1890s. Muddy spent his college years on the canal and spent many of his working years in a factory building overlooking the canal. Over the years he has traveled much of the canal system by boat and by bicycle. Muddy Paddle's Erie Canal adventure will return next Friday! To read other adventures by Muddy Paddle, see: Muddy Paddle: Able Seaman, about Muddy Paddle's adventures on the replica Half Moon, and Muddy Paddle's Excellent Adventure on the Hudson, about his canoe trip down the Hudson River.

The History Blog is supported by museum members and readers like you! Donate or join today! Editor’s note: This article contains racial slurs quoted as part of period newspaper articles and advertisements. In the summer of 1881, the Kingston Daily Freeman ran a series of articles about what became known as “glee clubs,” made up of Black or “colored” crewmembers of the steamboats Mary Powell and Thomas Cornell. The prevalence of singing aboard steamboats on the Mississippi is well-documented. Sea musician Dr. Charles Ipcar documented some of this history in “Steamboat and Roustabout Songs.” Roustabouts, also known as stevedores, were regular or short-term dock workers who primarily moved cargoes and fuel on and off steamboats. In the American South, these laborers were primarily Black, and coordinated loading by singing, keeping the freight moving to a rhythm – much like sailboat crews would coordinate hauling lines by singing sea shanties. When these songs were doubly coordinated with specific dance moves, they were known as “coonjine.”[1] It is unclear whether or not Hudson River steamboats also had crews of roustabouts or stevedores who sang at their work. Most of the bigger steamboats were designed for passenger use, so the only cargoes were fuel and food for the trip, and passenger’s luggage. One newspaper article from 1890 indicates that Southern Black longshoremen did come north for work in New York Harbor, particularly after white longshoremen were organizing unions and strikes.[2] That same article also indicated that at least one “Mississippi roustabout” was leading a group in singing roustabout songs. But while it’s not clear that steamboat crew on the Hudson River sang regularly, references to Southern roustabouts and their songs did occur frequently in New York. Roustabout songs were often among those included in minstrel shows - often performed by white musicians in blackface enacting racist caricatures of the Black Americans they purported to emulate. The popularity of minstrel shows and music date back to the 1830s, but during Reconstruction (1865-1877), many Black Americans saw career opportunities in taking control of the narrative and performing their own minstrel shows. Minstrel shows were among the most popular form of entertainment in 19th Century America. Many romanticized plantation life and depicted enslaved people as simple and happy with their enslavement. These depictions just as popular, if not more so, in the North than the South. Below are two examples from New York newspapers. The headline “Mississippi Roustabouts” is a racist account of visiting the Mississippi, published in the Buffalo Evening News, September 15, 1904. The second is an advertisement for the Glens Falls Opera House advertising the show “The Romance of Coon Hollow,” a popular show that opened on Broadway in 1894. Songs or scenes listed in the advertisement include "The Great Steamboat Race" and "The Jolly Singing and Dancing Darkeys." These are just two examples of how racial caricatures of Southern and Black life had entered the mainstream popular culture in New York in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It is against this complicated backdrop that we encounter the “glee clubs” of the steamboats Mary Powell and Thomas Cornell. Initially referred to as “colored singers” (the “glee club” title came later), our story begins on July 29, 1881, with a short article in the Kingston Daily Freeman called “Musical Talent on the Cornell” : “The steamer Cornell’s colored boys are fast coming into prominence as good singers, and it is believed that in a short time they will organize themselves into a vocal club. Wednesday night when the famous vocalist Mrs. Osborn favored the Cornell people with some selections from her repertoire, the boys started plantation songs and Mrs. Osborn, as well as several gentlemen on the steamer who are good judges of music, stated that the singing was excellent. If they organize they will give the Mary Powell singers a challenge to prove which of the two clubs is better.”[3] Four days later, the Freeman followed up with “A Challenge” : “The Mary Powell Colored Singers Challenge the Singers on the Cornell. “Last Friday evening the Freeman published an item commending the singing of the colored deckhands [dockhands?], cooks, etc. on the Thomas Cornell, and also said there was a prospect that they would organize themselves into a vocal club and then compete with the famous Mary Powell singers as to which is the better club. The Powell boys saw the article in the Freeman and are ready for the fray. They desire us to challenge the Cornell’s singers for a prize of $50, the contest to come off at any time the Cornell vocalists may select within the next two weeks; the place, judges and other arrangements to be mutually agreed upon. Several of the Powell crew have belonged to professional troupes, and they feel confident of outsinging their formidable rivals. One or two of them will stake $5 apiece on the contest. It is thought a good idea in the event of a match ensuing that some large hall be hired and that a small admission fee be charged, which will somewhat defray expenses. No doubt a large audience would witness the match. Come, Cornell boys, accept this challenge and show your prowess. You will have to work hard, though, for the Powell singers are very good.”[4] It is unclear whether or not these groups were simply recreational clubs for employees of their respective steamboats, or if the groups performed while on the job. The Mary Powell did have a reputation for musical entertainments, but according to surviving concert handbills, these were usually orchestral performances of classical music. In addition, one photo of the Mary Powell orchestra survives, and this incarnation at least, from 1901, is all white. Eight days after the Freeman suggested a formal singing contest, the Kingston reading public got just that. “Cornell-Powell Singers,” published on August 10, 1881, reads: “A Prize Singing Match for $50 a Side to Come Off Within a Short Time. “About three weeks ago the colored singers on the Thomas Cornell were lauded by the Freeman for their excellent vocal accomplishments and at the same time we proposed the starting of a singing match between them and the famous Mary Powell singers. The Powell boys saw our article and authorized us to challenge the Cornell singers for a prize singing match, which we did and as a culmination of arrangements toward such an end a committee from the Cornell waited upon the Powell men yesterday morning to accept the challenge. Accordingly some time within the next three weeks Kingston will witness a first-class prize singing match in either Sampson Opera House or Music Hall for a prize of $50. Each club is to select and sing its own songs. Both clubs are now organized for business under the title of the “Cornell Glee Club” and the “Mary Powell Glee Club.” Constant practicing from now until the match comes off will be in order on these two steamers and passengers will have a rare treat.”[5] By renaming themselves as “Glee Clubs,” the steamboat employees were staking territory as professional singing groups. Originally created in 18th century England, glee clubs were small groups of men singing popular songs acapella, often with close harmony. Started on college campuses in the Northeast, glee clubs soon spread across the country, but remained primarily the domain of white men. By the end of the 19th century, many of these groups were regularly singing minstrel music and “Negro spirituals,” often in blackface.[6] The two groups of steamboat employees may have simply decided that being a “glee club” was more descriptive than “colored singers,” or more respectable, or might raise more interest among the general public. The last sentence of the above article is also an interesting one, implying that the groups planned to practice, if not perform, while at their work aboard their respective steamboats. The reference of the songs being “a rare treat” indicates that singing while working aboard was not a common occurrence. By August 12, the date was set. The Daily Freeman reported that the match would take place on August 20, 1881. Tickets were “thirty-five cents for general admission, and reserved seat tickets will be sold at fifty cents.”[7] The Poughkeepsie Daily Eagle advertised the same.[8] Two days after the concert took place, the Poughkeepsie Daily Eagle published a full account of the event, “Singing for a Prize: Mary Powell vs. Thomas Cornell” : “We extract from the Rondout Courier’s account of the singing match at Music Hall, Kingston, Saturday evening, so interesting report of the contest between the colored employees of the Thomas Cornell and Mary Powell. “Music Hall was a scene of most intense interest on the occasion. Our colored friends seemed to [own?] the whole town, and the great hall, although too large for the audience, as too small for them – Prof. [Jack?] Miner was Judge. “As the Powell was late and the Cornell early, the Cornell Club was first on the stage. The stateroom [eight?] of the Cornell came upon the stage with determination written upon every brow. They are darker and sturdier than their competitors, looking more like plantation hands, as befits a freight boat [editor's note - the Thomas Cornell was a passenger boat, not a freight boat]. They had more depth of hold and breadth of beam, and there was more solidity about them. Their bass was very bass indeed, Mr. Lew Vandermark scraping the very [lowest?] of his lower notes, and the leader, Aug. Fitzgerald, kept steadily the main channel of his tubes. The marked [characteristics?] of the two clubs were brought out very distinctly when the Cornell Club, at the hint of George F. [?] sang, “Mary had a little lamb,” which had been previously rendered by the Powell boys. In this the “baaing” of the lamb is given, with variations. “The Powell boys are of lighter build and complexion than their competitors. They sing out their notes with a sort of twirl, as if one had ordered 'broiled blue fish' or 'Spanish mackerel,' with Saratoga potatoes, while the Cornell boys came up with the mere solid beefsteak and boiled murphies of a 'stateroomer supper.' “The members of the clubs were as follows: "Cornell Glee Club – Aug. Fitzgerald, leader; L. Schemerhorn, Eugene Harris, [Dav.?] Johnston, George Dewitt, Lew Vandemark, Chas. Van [Gaasbeck?], Dennis Johnston, Miss [Lizzie?] Hartly, pianist. "Powell Glee Club – I. P. Washington, leader; J. C. Washington, James Poindexter, Wm. McPherson, B. G. Smith, Robert Martin, Harry Coulter, Prof. John [Mougan?]. The latter also acted as pianist. “The audience was a fair one. It thoroughly enjoyed itself, an after the crews got fairly warmed up it got considerably excited, and stamped and shouted and clapped in the wildest manner, winding up in a round of cheers. “The Cornell Club mainly confined itself to pious tunes; “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” “Prepare Me Lord,” and the like, filling the programme, while the Powell boys had lighter pieces and evinced a strong preference for [fancy?] [selections?]. The Cornell crew sang “Sweet Ailleen” very prettily, and did better with the songs than the hymns. “The audience was well pleased with “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” and “Oh Them Union Brothers,” in which the Cornell crew caught the wild melody nicely. The Powell followed with “Hark, Baby, Hark,” sang very prettily indeed, and “Row the Boats,” in which the sweep of the melody is very sweet. The Cornellites came up smiling with their religious tunes, of which “Pray all along the Road” was the most noticeable. Then came one of the gems of the evening, “Night Shades,” by the Powell boys, which the audience was highly pleased with and “Old Oaken Bucket,” which they sang nicely. For an encore they dipped into the religious vein, which seemed to stir up the Cornellites, who retorted with “Mary had a Little Lamb,” with which the Powellites had previously brought down the house. The version was a little different, but both took with the house. The audience at this point applauded the Cornellites very heavily, which caused the Powellites to bring out their best and “Mary Gone with a Coon” was given. “The programme was finally closed with the Powell boys singing “Good Night” when Geo. F. [Kjerstad? Kjersted?] brought forward Prof. Miner. He made a few remarks in which he said he had tried to perform his duty as Judge honestly, and then disclosed that the victory rested with the Mary Powell club, when there was great applause, and the audience died slowly out.”[9] Here we finally get some details! We have names of the participants, for one, and details of the concert itself, including the songs. Sadly, we also have a complicated blend of admiration and racism. Of the Cornell singers, the author writes, “They are darker and sturdier than their competitors, looking more like plantation hands, as befits a freight boat.” (Note that the Thomas Cornell was a passenger vessel build specifically to rival the Mary Powell, not a freight boat.) Whereas, “The Powell boys are of lighter build and complexion than their competitors. They sing out their notes with a sort of twirl, as if one had ordered ‘broiled blue fish’ or ‘Spanish mackerel,’ with Saratoga potatoes [potato chips], while the Cornell boys came up with the mere solid beefsteak and boiled murphies [potatoes] of a ‘stateroomer supper.’” Here, the author conflates appearance with singing talent, implying that the more slender and lighter complexioned “Powell boys” sang with more delicacy and finesse than the darker complexioned “Cornell boys.” One wonders if the Mary Powell crew were specifically selected for employment due to their lighter skin tone, or if it was simply coincidental. Shades of blackness and whiteness were very important in the racial hierarchy of the United States, with lighter skinned people often receiving better or preferential treatment when compared with darker skinned people. The persistent use of the term “boy” to refer to Black adult men is also a racist microaggression, designed to imply inferiority when compared to white men. Ultimately, the Mary Powell crew were declared winners, a result backed up by a single line in the New Paltz Times on August 24, 1881. Although many of the songs listed are unfamiliar to modern audiences, “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” has persisted, as has “Mary Had a Little Lamb,” which was interestingly performed by both groups. Preliminary search results for the members of the two glee clubs both before and after the concert resulted in few hits, although by 1903, a Lew Vandemark was part of a group called “Smith’s Colored Troubedours,” which gave a performance before the cakewalk at “Charley Conkling’s Masquerade” in Middletown, NY.[10] If you would like to assist us by researching these men (and one woman!), their names are as follows. Thomas Cornell Glee Club members:

Mary Powell Glee Club members:

I have found no further reference to either glee club, nor similar groups connected to Hudson River steamboats, but I hope that by sharing these stories we can discover more information about the club members and their work. If anyone would like to see original images of the newspapers, or has leads on any of the people listed above, other references to the glee clubs, or to other singing clubs associated with steamboats, please contact us at [email protected]. FOOTNOTES: [1] Charles M. Ipcar, “Steamboat & Roustabout Songs,” paper presented at the 2019 Mystic Seaport Sea Music Festival. [2] “Colored ‘Longshoremen,” The Sun [New York], March 23, 1890. [3] “Musical Talent on the Cornell,” Kingston Daily Freeman, July 29, 1881. [4] “A Challenge,” Kingston Daily Freeman, August 4, 1881. [5] “Cornell-Powell Singers,” Kingston Daily Freeman, August 10, 1881. [6] “Glee Clubs – Minstrelsy & Negro Spirituals,” University of Richmond Race and Racism Project, https://memory.richmond.edu/exhibits/show/performancepolicy/glee-clubs---minstrelsy---negr [7] “The Cornell-Powell Prize Singing,” Kingston Daily Freeman, August 12, 1881. [8] Untitled, Poughkeepsie Daily Eagle, August 17, 1881. [9] “Singing for a Prize: Mary Powell vs. Thomas Cornell,” Poughkeepsie Daily Eagle, August 22, 1881. [10] “Charley Conkling’s Masquerade,” Middletown Daily Press, November 23, 1903. AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson is the Director of Exhibits & Outreach at the Hudson River Maritime Museum and is the co-author and editor of Hudson River Lighthouses, as well as the editor of the Pilot Log. She has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and has been with the museum since 2012. Filmmaker Ken Sargeant has compiled many of Henry's stories, including with footage from a filmed oral history interview, into "Tales from Henry's Hudson." In 2013, Arts Westchester put together this short video of Henry, combining oral histories from the Hudson River Maritime Museum and film interviews by Ken Sargeant. You can watch more of Henry on film below: For today's Media Monday, we thought we'd highlight one of the best storytellers on the Hudson River. Henry Gourdine, a commercial fisherman on the Hudson River since the 1920s, was a famous advocate for the river and its fishing heritage. Born on Croton Point on January 7, 1903, his reminiscences of growing up along the waterfront, defying his mother to spend time there, and his working life on the river, captured the imagination of the region at a time when commercial fishing was under threat from PCBs. A boatbuilder, net knitter, and fisherman, as well as a storyteller, Gourdine helped preserve many of the fishing crafts. He taught boatbuilding and net knitting at South Street Seaport, recorded descriptions of many heritage fishing methods on tape, and would happily talk about the river and fishing to anyone who asked. Henry Gourdine passed away October 17, 1997 at the age of 94. Read his New York Times obituary. In 2006, the New York Times published a retrospective on the impact of Henry Gourdine on local communities throughout the valley. Henry Gourdine on FilmHenry Gourdine Oral HistoryThe Hudson River Maritime Museum has an extensive collection of oral history recordings of Hudson River commercial fishermen. Marguerite Holloway interviewed Henry Gourdine several times between 1989 and 1994, covering a whole host of fishing-related topics. Those oral histories now reside at the Hudson River Maritime Museum and have been digitized for your listening and research pleasure. Click the button below to take a listen! Henry Gourdine's Fishing ShackBuilt in 1927, Henry Gourdine's fishing shed stood for decades along the Ossining waterfront. But the days of the working waterfront were over, and Ossining sold the property to developers in the early 2000s. By 2006, work was set to begin, and Henry's shed was not part of the for condominiums overlooked the Hudson River. Despite pleas from local conservationists and the Gourdine family, including a temporary injunction from a court, the shed was ultimately demolished in May, 2006. Henry's fishing equipment and two boats were salvaged from inside and saved by Arts Westchester and family members. Preservationist and cataloger of ruins Rob Yasinsac cataloged the shed and its contents in April, 2006, before it was bulldozed. Read his account and see more pictures. Sadly, the development soon stalled, and ground was not broken on the condos until 2014. Henry Gourdine ParkPerhaps as an apology for the demolition, the condominium development known as Harbor Square created a waterfront park and named it Henry Gourdine Park in honor of the man who fished off its shores for nearly 80 years. The park was opened in June, 2018. You can learn more about the park and its amenities and visit yourself. Today's Featured Artifact is a fan favorite - it's the biggest artifact in our collection, and one of the few housed outdoors. It's the 1898 steam tugboat Mathilda! And yes, she really is an artifact! She even has her own accession number - 1983.34.1, donated by the McAllister Towing Company. Accession numbers are how museums keep track of their collections. Each number is unique to an object and the number itself tells part of the story. For Mathilda, she was the 34th donation received in 1983, and the first item in the collection. The 1898 steam tugboat Mathilda was built in Sorel, Quebec, and for many years worked on the St. Lawrence River and the Great Lakes. Originally, coal fueled her steam boilers. Later her engine was changed to an oil-fired, two-cylinder reciprocating unit. McAllister Towing bought the Mathilda and brought her to New York Harbor after using her in Montreal berthing ships. 1969 was her last year of active service. In 1970 McAllister donated Mathilda to South Street Seaport in lower Manhattan. In January, 1976 the Mathilda sank at her pier at the Seaport. She was raised by the Century floating crane. Since the Seaport could not afford the needed repair work, Mathilda was moved to the former Cunard Line Pier 94 for dry storage. In 1983 McAllister Towing donated the Mathilda to the Hudson River Maritime Museum, and sent her to her new home on the Rondout on the deck of the Century crane barge which placed her in the yard of the Museum. In recent years the Mathilda has been permanently stabilized and her appearance restored with authentic McAllister paints supplied by the company. Her deck lighting has been restored and enhanced. Her interior has been cleaned out, and a window opened for viewing her engines, which are lit at night. As one of the last tugs in existence with her original steam engine, the Mathilda is a proud survivor of the type of tugs which served on the Hudson and elsewhere for nearly 100 years. You can visit Mathilda any time at the Hudson River Maritime Museum. Stop by and say hello! If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor’s Note: Welcome to the next episode in our 11-part account of Muddy Paddle's narrowboat trip through the Erie Canal and the Cayuga & Seneca Canal in western New York. The New York State Barge Canal system is in many ways a tributary of the Hudson River. It still connects the Great Lakes, the Finger Lakes, and Lake Champlain with the Atlantic Ocean by way of the Hudson River. Our contributing writer, Muddy Paddle, shares his experiences aboard the "Belle Mule." All the included illustrations are from his trip journal and sketchbooks. Day 2 - SundayThe Belle was comfortable for a boat of her size. The wood paneled cabins were warm and attractive, the layout was convenient and there was plenty of headroom. Shelving, cabinets and drawers used space efficiently and the window ports were dressed with curtains. A packet boat of the kind used on these canals before the Civil War would have been nearly twice as long, but would have carried dozens of passengers, segregated by gender and fit into bunks that could be folded away or otherwise removed during the day. Our boat cruises at about five or six miles per hour, only slightly better than its horse drawn predecessors. Mule drawn freight boats were slower. After an infusion of coffee, we cast off our lines and headed for Lock 4 and Seneca Lake beyond. Lock 4 is in the village and takes boats up to the lake level. We radioed the lock in advance of our approach and had a green light and open gates when we arrived. I got the boat lined up nicely on the right side of the lock chamber and put the shift into neutral so I could leave the pedestal and take hold of one of the hand lines to keep the boat parallel and next to the chamber wall. Brent did the same in the bow. We started having problems as soon as the doors closed behind us. First, the boat would begin to creep forward and Brent would yell that he couldn’t hold his line any more. I would go back to the pedestal, give the boat a few revolutions of reverse, go back to neutral and then run back to grab my line. But then the boat would creep backwards. She was living up to her name the Belle MULE!” I was grateful when the chamber was full and the gates opened at the upper end. We encountered a stiff current carrying excess lake water east over the spillway and had to use the bow thruster to remain on course. Two miles west, we stopped at a dock and walked up to Route 20 to visit the Scythe Tree, a local point of interest with a sad story. James Wyman Johnson enlisted in the Union Army in 1861 and left his scythe in the crotch a cottonwood tree near his family’s farmhouse. He asked that it remain there until his return. He died of battle wounds in a Confederate prison in Raleigh and never returned to the farm. The tree grew around the scythe. When the United States entered World War I, two brothers living on the farm, Ray and Lynn Schaffer, enlisted, placed their scythes in another crotch of the tree and found them embedded in the tree, when unlike Johnson, they returned safely. All three scythes remain in the big tree. We continued our cruise west into Seneca Lake and set a course for Belhurst Castle on the west shore of the lake below Geneva where we had made brunch reservations. However, we realized that it was getting late and a long brunch, not to mention the steep ascent up from the dock, would burn up hours and delay our efforts to reach Watkins Glen and find a berth. It was also beautiful weather, so we cancelled our reservations and continued our cruise, viewing the big Victorian house from half a mile out. We steered well clear of a sailboat race underway at the north end of the 36-mile long lake. In addition to its considerable length, Seneca Lake is also more than 600 feet deep and littered with the wrecks of dozens of canalboats, steamboats and other craft from its long history of use. Many of these went down in bad weather and as a result of accidents (maybe this is why the boat rental companies prohibit their canalboats from venturing out onto the lakes….). Others were scuttled here at the end of the animal powered canal era. One of the best wrecks for divers to visit is located along our course below Geneva in Glass Factory Bay at a depth of about 115 feet. Unfortunately, visiting divers were careless some years earlier and dragged an anchor through the intact canalboat, carrying its lightly framed cabin top off the boat and over the side. Traveling south at about six miles per hour, we reached the power plant near Dresden late in the morning and the Navy training platform in the center of the lake around 1:00 PM. The derrick-studded platform is now leased as a research facility but some years ago it represented the center of a highly classified experimental submarine warfare station and was heavily guarded by armed sentries and patrol boats. Shauna and Lora relaxed and soaked up the sun in lawn chairs set up in the bow. Women passengers aboard the packet boats were similarly offered chairs in the bow to enjoy their journeys. Watkins Glen is located at the south end of Seneca Lake and we began making calls and using the radio in an effort to find a berth for the Belle. The most likely facility was Village Marina but we were unable to make contact. After passing several very large cruising sloops and a schooner we arrived at a rip rap breakwater protecting the marina. The radio crackled and we were told to switch to channel 66. Once there, Captain Terry, the marina manager, told us that he had a berth available. He sounded agitated. He told us to enter the basin between two drunken pilings; turn sharply right and then approach the T-dock “under spirits.” As we entered, we could see that there was very little space to maneuver and that there were plenty of big and expensive fiberglass cruisers to stay clear of. I threw the transmission into reverse to kill our momentum, spun the wheel to starboard and then crawled forward. A crowd emerged outside of the bar to watch the expected pile-up. We could see that we would need to parallel park because there was no room to turn the Belle around. A gentle breeze helped us line up and a bystander threw us a line at exactly the right moment. We made a clean landing, secured our lines and shut down the engine. A greeting committee gathered with drinks for us and we felt obliged to graciously open up the boat to them to satisfy their curiosity. One woman on her fourth martini made herself at home in the salon where she held court. Captain Terry raced in from the lake to see if we had done any damage to the expensive boats or the docks. Seeing that we were well secured and seemingly accepted at the marina, he relaxed a little and explained that hire boats like ours make him nervous. A similar boat crashed and sank on the inside of the stone breakwater in a previous year. Recalling the incident, he said, “you know a guy is in trouble when you see his wife yelling at him, his daughter tugging on him and his mother-in-law giving him instructions as he tries to dock a big boat.” After tidying up and gently asking Mrs. Martini to leave, we walked into Watkins Glen, explored Main St, and got bad directions to Walmart where we planned to buy groceries and ice. We returned to boat much more directly using a shortcut along the railroad tracks. Brent found that our grille had no gas, so he made a second trip to Walmart to get some so that he could grill chicken for dinner on the bow. Shauna and Lora prepared salads and rice in the galley. We set up folding chairs on the cabin top and had a relaxing dinner as the sun set. Sailing cruisers and an excursion boat sailed in and out of of the harbor with red and green running lights as it got darker. We retired to the cabin for a spirited game of Pictionary and fell asleep quickly as the sea gulls squealed overhead. We slept restfully as the Belle swayed gently to the lake swells. AuthorMuddy Paddle grew up near the junction of the Hudson River and the Erie Canal. His deep interest in the canal goes back to childhood when a very elderly babysitter regaled him with stories about her childhood on the canal in the 1890s. Muddy spent his college years on the canal and spent many of his working years in a factory building overlooking the canal. Over the years he has traveled much of the canal system by boat and by bicycle. Muddy Paddle's Erie Canal adventure will return next Friday! To read other adventures by Muddy Paddle, see: Muddy Paddle: Able Seaman, about Muddy Paddle's adventures on the replica Half Moon, and Muddy Paddle's Excellent Adventure on the Hudson, about his canoe trip down the Hudson River.

The History Blog is supported by museum members and readers like you! Donate or join today!  Undated photo of Steamer Mary Powell crew posing on deck with Captain A.E. Anderson, center front row with newspaper. 1st row: Fannie Anthony stewardess; 4th from left, Pilot Hiram Briggs; 5th, Capt. A.E. Anderson (with paper); 6th Purser Joseph Reynolds, Jr. Standing, 3rd from left: Barber (with bow tie). Black men at right possibly stewards. Donald C. Ringwald collection, Hudson River Maritime Museum. The history of Black Americans is often purposely erased, so when conducting research for our new exhibit, “Mary Powell: Queen of the Hudson,” I was delighted to find several references to Black and African-American crew working aboard the Mary Powell. One of the first clues we found was a photo of the crew, including a lone woman – Fannie M. Anthony [also spelled “Fanny”] – who was listed as the “stewardess” of the Mary Powell. Clearly Black or mixed race, I had to find out more about this intriguing woman. Although the research wasn’t especially easy, it was less difficult than I expected, because it turned out that Fannie was famous. Fannie M. Anthony was born on June 27, 1827 in New York City. Often listed in Census records as “mulatto,” according to a 1907 Daily Freeman article, “[h]er father was an East Indian, and her mother a full-blooded Indian of the Montauk tribe.”[1] In Census records, her father, Charles R. Smith is listed as “mulatto” and born in 1797 in New York (with his father listed as being born in Nevis, West Indies and his mother in New York), and her mother, Mary Walker, as born on Long Island.[2] It is certainly possible that her mother was Montauk, but it is unlikely that her father was East Indian. Few, if any East Indians emigrated to the United States before 1830. In the 1900 Census and her 1914 death record, her race is listed as Black.[3] Many people of African descent often concealed their heritage in an attempt to deflect the worst effects of racism. In addition, census takers and journalists were often subject to their own personal biases, conscious or unconscious, and assigned race accordingly. Fannie’s husband was Cornelius Anthony, born in 1825 in New Jersey. Census records also list him as “mulatto,” and the 1880 Census lists him as a steward aboard a steamboat. [4] Sadly, it does not indicate which one, although his 1900 obituary lists him as working aboard “Albany boats.”[5] It would be kismet if he and Fannie both worked aboard the Mary Powell, but that cannot be confirmed. He is listed as a carpenter in the 1900 Census, but other information in that record, including the spelling of names and birthdates, is inaccurate. Cornelius died on or before Monday, July 16, 1900. The following day, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle published his obituary. It read, “Jamaica, L. I., July 17 – Cornelius Anthony, aged 69 years, a negro, a well known and respected resident of this place, died at his home on Willow street on Friday. Deceased was for many years head steward on the Albany boats and was known as a caterer of considerable note. He was at one time sexton of the Methodist Church of Jamaica. He leaves a widow and many near friends and relatives. Internment was made yesterday, at Maple Grove Cemetery.”[6] An 1894 article in the Brooklyn Times Union indicates that he was sexton of the Methodist Episcopal Church at that time. Although we do not know which vessels he worked on as a steward, he must have had considerable skill in his management of the dining rooms, as his obituary also notes his fame as a caterer. It is unclear when Fannie began her work as the “chambermaid” of the Mary Powell, although sources (listed below) suggest a start date of 1869 or 1870. Her occupation in the 1880 Census, at age 52, is listed as “steamer chambermaid.” Identified alternately as “chambermaid,” “stewardess,” and “lady’s maid,” Fannie worked in the “ladies’ cabin” of the steamboat Mary Powell. In a private home, a Victorian era chambermaid cleaned and maintained bedroom suites. Ladies’ maids assisted upper class women with dressing, cared for their wardrobe, and dressed hair. As a day boat, the Mary Powell did not have sleeping cabins, so it is likely that the “ladies’ cabin” was a “saloon” or public indoor space designed specifically for women, likely including toilet facilities, couches, and other private comforts. Since the days of Robert Fulton’s North River Steamboat, a separate, private cabin for women was reserved, allowing delicate Victorian sensibilities to relax, knowing that white women were protected from the attentions of single men. Fannie Anthony likely would have cleaned and maintained this space and assisted female passengers with requests, much like the steward would do for the rest of the steamboat. In all likelihood, as a “stewardess,” Fannie’s role was probably similar to that of a housekeeper in a wealthy household. Her husband Cornelius, as a steward, likely had a job similar to a household butler. In particular, he would oversee dining facilities and public spaces, ensuring their cleanliness and smooth operation, and overseeing waitstaff, porters, etc. One of the earliest newspaper articles about her is a very complimentary one. Published in the Monday, September 17, 1894 issue of the Brooklyn Times Union, it quotes the Newburgh Sunday Telegram. The article, titled, “Compliments for a Jamaica Woman” reads: “A correspondent of the Newburgh Sunday Telegram speaks very pleasantly of Mrs. Fannie Anthony, for many years stewardess of the North River steamer Mary Powell. Mrs. Anthony is a Jamaica woman, and the wife of Cornelius Anthony, sexton of the Methodist Episcopal Church in Jamaica. The correspondent says: “’Mrs. Fannie Anthony, the efficient and obliging stewardess on the steamer Mary Powell, is about concluding her twenty-fifth season in that capacity. Mrs. Anthony enjoys an acquaintance among the ladies along the Hudson River that is both interesting and highly complimentary to the amiable disposition and cheery manner of the only female among the crew of the favorite steamboat. Mrs. Anthony travels over 15,000 miles every summer while attending to her duties on the boat. She seldom misses a trip and looks the picture of health and happiness. Many are the compliments I have heard from Newburg ladies of the genial stewardess’ worth aboard the boat. Rich and poor are alike to her. Her smile and mien are as cheery on a stormy day as on one of sunshine. Every member of the crew pays the homage due her, and the Captain thinks the boat couldn’t run without the stewardess. She is the second oldest traveler now aboard the vessel, but this statement does not imply that Mrs. Anthony is by any means very old. She is well preserved and active, and in every way a credit to her sex and race. Good luck to her.’”[7] Note that the “Jamaica” woman refers to Jamaica, Long Island – it does not connect Fannie to the Caribbean island of Jamaica. If she was finishing her 25th season in the fall of 1894, that gives her a start date of 1869. This article is very respectful, particularly when compared with subsequent publications. Fannie is referred to as “Mrs.” and by her full name. A 1902 New York Press article about her, when she would have been 75 years old, writes, “She looks as young as when she bustled about in the saloon in 1860, her chocolate complexion betraying no ravages of time.”[8] It is unlikely that Fannie started in 1860. For one, the Mary Powell was not even built until 1861. In addition to the Brooklyn Times Union reference, which indicates a start date of 1869, a 1907 article in the Daily Freeman indicates that she had been in service aboard the Mary Powell “for thirty-seven continuous years,” giving her a start date of 1870.[9] Regardless of when she actually started her work, by the turn of the 20th Century she was a Hudson River legend. An issue of the Newburgh Register from sometime after August 12, 1900 reads, “Mrs. Fannie Anthony, who for the past thirty years has been employed as a lady’s maid on the steamer Mary Powell, is spending the summer at Kingston, her daughter having taken her position on the Powell.” But clearly, as subsequent articles indicate, Fannie did not retire in 1900 and no mention is made of which daughter may have ultimately taken her place. She is mentioned again in the May 6, 1902 issue of New York Press. In a gossip column entitled, “On the Tip of the Tongue,” following a brief description of the Mary Powell, there is a whole section entitled “Fanny.” The article is transcribed verbatim: “’Fanny’ is known to a majority of regular travelers on the Hudson as the stewardess of the Mary Powell, a billet she has held ever since the boat was launched. No one knows her age, but it must be 80. She looks as young as when she bustled about in the saloon in 1860, her chocolate complexion betraying no ravages of time. The multitudes that have been in her care never bothered to inquire about her surname, but accepted her as ‘Fanny,’ and ‘Fanny’ she is to all. This good woman and my old friend H. R. Van Keuren are the only two living of the early crew of the Mary Powell. ‘Van’ has just celebrated his fiftieth birthday. He resigned the stewardship of the boat in 1876, I think, and got rich in another business. Recently when he stepped upon the deck of the Mary, who should run up and throw her arms about his neck but faithful old ‘Fanny?’”[10] In reality she was 75, not 80 years old. This article, like several that follow, speak of Fannie in a condescending way, consistent with the racism of the day. In addition, Fannie’s position as chambermaid or stewardess meant that she was likely treated as a servant, albeit an upper level one. Hence the passengers never bothering to “inquire about her surname.” A stark contrast to the earlier, more respectful article of 1894. On Wednesday, July 24, 1907, The Kingston Daily Freeman published on page 8 an article entitled, “Fannie of the Powell: A Character and Fixture on the Steamer.” It reads: “Almost everyone who has even been on the Mary Powell has seen the stewardess, ‘Fannie,’ says the Poughkeepsie Star. She has been on the boat for thirty-seven continuous years. Her name is Fannie M. Anthony. Her father was an East Indian, and her mother a full blooded Indian of the Montauk tribe. She has the shoes that her grandmother was married in, and a copper kettle one hundred years old. She is a very fine looking woman, and talks history with authority. She has met in her time thousands of people, the majority of whom have passed away. All the prominent men who travel shake hands with Fannie and have an old-time chat with her. She is exceedingly interesting and full of [maint?] humor. She hates a snob, and knows ladies and gentlemen at sight. Fannie is the pet of the public and the faithful and honored servant of the Powell.”[11] This article reflects the changing times and a new veneration for elders who had lived through a history-making era. The references to the 100-year-old copper kettle, her grandmother’s shoes (perhaps Montauk), and all the people who have “passed away” is not only establishing her as someone who can “[talk] history with authority,” but also establishing her as a third-generation free American, distancing her from the possible taint of slavery. Her role in public service and her long tenure aboard the Mary Powell led to her fame and the fondness with which newspapers and general public spoke of her. Fannie retired from the Mary Powell in 1912, at age 85. She died on May 26, 1914 in Queens, just short of her 87th birthday, and was buried May 28, 1914 in Maple Grove Cemetery, in Kew Gardens, Queens.[12] Her husband Cornelius was also buried in Maple Grove Cemetery. Like Cornelius, she received a formal published obituary, emphasizing her status and fame in the community. On Thursday, June 4, 1914, the Poughkeepsie Evening Enterprise published “Aunt Fannie, of the Mary Powell Dies:” “Mrs. Fannie Anthony, who for 39 years was chambermaid in charge of the ladies’ cabin on the steamer Mary Powell, died at her home at Jamaica, Long Island, on Friday, aged 87 years. She was in active service on the Powell until failing health and advancing years compelled her to give up her work two years ago, when she was succeeded by her daughter. To the traveling public she was familiarly known as ‘Aunt Fannie,’ and hundreds of visitors on whom she waited during her service have pleasant recollections of her. She began under the late Captain Frost, and continued under Captain Absalom Anderson, Captain ‘Billy’ Cornell and Captain A. Elting Anderson.”[13] Two days later, on Saturday, June 6, 1914, Fannie made front page news in the Rockland County Journal – “Aged Chambermaid of Mary Powell Dead” – a verbatim reprint of the above Evening Enterprise obituary.[14] The nickname “Aunt Fannie” is a complicated one. On the one hand, it likely was used by most as a term of endearment. However, the use of the word “aunt” in relation to older Black women in the 19th and early 20th century, especially by white people, is often a derogatory honorific. By using the terms “aunt” and “uncle,” white people could avoid using the more respectful “Mrs.” And “Mr.” with elder people of color, maintaining the racial hierarchy of white supremacy. People of all races in service were often referred to only by their first name as a way of highlighting their subservient role. At the same time, the Evening Enterprise also refers to her as “Mrs. Fannie Anthony,” giving her the proper honorific. Here we also have confirmation that she was, indeed, succeeded by her daughter, although we still do not know which one. An Ada Anthony, granddaughter of Charles R. Smith (and therefore probably Fannie and Cornelius’ daughter) is listed in the 1880 Census, born in 1862.[15] By the 1910 Census, Cornelius is dead and Fannie is living alone with her widowed daughter (listed as granddaughter in the 1900 Census) Mary R. Smith and a boarder.[16] Newspaper searches for Ada and Mary have so far revealed no leads. The Mary Powell itself was taken out of service in 1917, just five short years after Fannie’s retirement. Fannie M. Anthony walked a delicate balance in the 19th and 20th centuries aboard the steamboat Mary Powell. Although she occupied a service role, often one of the few avenues of employment open to Black people, it seems that through sheer force of personality, excellence, and longevity, she managed to overcome some of the obstacles that faced most women of color at the time. Like the steamboat Mary Powell herself, Fannie achieved a measure of fame not usually afforded ordinary people. I hope that by sharing Fannie Anthony’s story, we can help bring more details of her life and her family to light. If you have any information about the Anthony family not featured here, please contact the Hudson River Maritime Museum. We will update this article with more information when possible. Footnotes: [1] “Fannie, of the Powell,” Kingston Daily Freeman, July 24, 1907. [2] “Chas R. Smith” listing, US Census, 1880. [3] “Cornelus Anthony” listing, US Census, 1900; “Fannie M. Anthony” New York City Municipal Death Record, May 26, 1914. [4] “Chas R. Smith” listing, US Census, 1880. [5] “Death of Cornelius Anthony,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 17, 1900. [6] “Death of Cornelius Anthony,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 17, 1900. [7] “Compliments for a Jamaica Woman,” Brooklyn Times Union, September 17, 1894. [8] “Fanny” within “On the Tip of the Tongue,” New York Press, May 6, 1902. [9] “Fannie, of the Powell,” Kingston Daily Freeman, July 24, 1907. [10] “Fanny” within “On the Tip of the Tongue,” New York Press, May 6, 1902. [11] “Fannie, of the Powell,” Kingston Daily Freeman, July 24, 1907. [12] “Fannie M. Anthony” New York City Municipal Death Record, May 26, 1914. [13] “Aunt Fannie, of the Mary Powell Dies,” Evening Enterprise [Poughkeepsie, New York], June 4, 1914. [14] “Aged Chambermaid of Mary Powell Dead,” Rockland County Journal, June 6, 1914. [15] “Chas R. Smith” listing, US Census, 1880. [16] “Cornelus Anthony” listing, US Census, 1900; “Fannie M. Anthony” listing, US Census, 1910. AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson is the Director of Exhibits & Outreach at the Hudson River Maritime Museum and is the co-author and editor of Hudson River Lighthouses, as well as the editor of the Pilot Log. She has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and has been with the museum since 2012. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

|

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 [email protected] Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |