History Blog

|

|

|

|

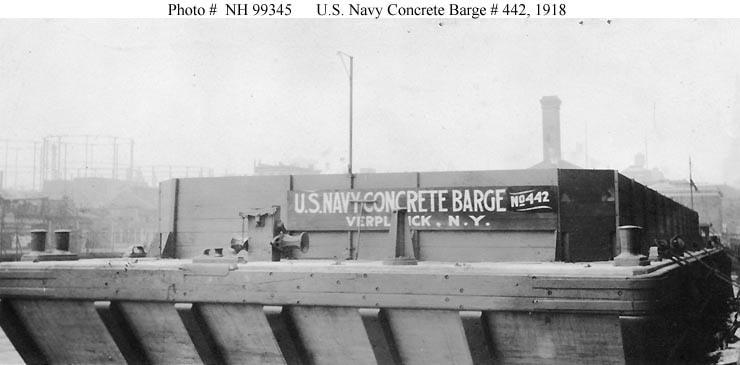

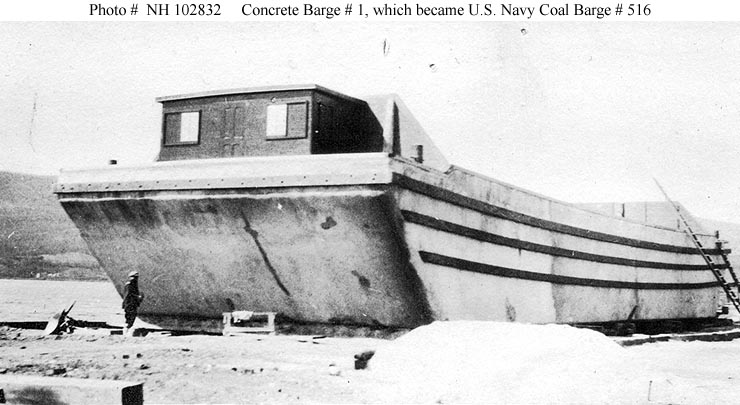

itle: Concrete Barge # 442 Description: (U.S. Navy Barge, 1918) In port, probably at the time she was inspected by the Third Naval District on 4 December 1918. Built by Louis L. Brown at Verplank, New York, this barge was built for the Navy and became Coal Barge # 442, later being renamed YC-442. She was stricken from the Navy Register on 11 September 1923, after having been lost by sinking. U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph. Hiding away in Rondout Creek, New York at 41.91245, -73.98639 is the last known surviving example of a World War I Navy ‘Oil & Coal’ Barge. It is less than a kilometer up the Rondout Creek from the Hudson River Maritime Museum. Based on a lot of ‘Googling’, it seems probable this is the first time that the provenance and history of this particular relic of concrete shipbuilding in the United States during the World War I era has been recognized. [Editor's Note: The concrete barge is featured on the Solaris tours of Rondout Creek.] The hulk is, in fact, the initial prototype of a ‘Navy Department Coal Barge’, concrete barges that were commissioned by the Navy Department : Bureau of Construction and Repair. This was the department of the U.S. Navy that was responsible for supervising the design, construction, conversion, procurement, maintenance, and repair of ships and other craft for the Navy. Launched on 1st June 1918, the ‘Directory of Vessels chartered by Naval Districts’ lists ‘Concrete Barge No.1’, Registration number 2531, as being chartered by the Navy from Louis L. Brown at $360 per month from 11th September 1918. In Spring 1918, the Navy Department had commissioned twelve, 500 Gross Registered Tonnage barges from three separate constructors in Spring 1918 to be used in New York harbour.  Navy Barge #516 which was the first prototype. It is believed that the barge at Rondout Creek is this particular barge based on the subtly different lines of her bow. Possibly photographed when inspected by the Third Naval District on 5 April 1918. She was assigned registry ID # 2531. This barge, chartered by the Navy in September 1918, was returned to her owner on 28 October 1919. While in Navy service she was known as Coal Barge # 516. U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph. AuthorsRichard Lewis and Erlend Bonderud have been researching concrete ships worldwide for many years. They have identified over 1800 concrete ships, spanning the globe, of which many survive. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

0 Comments

Editor's note: The following text is from the February 1937 issue of "The Open Road for Boys" magazine. The language, spelling and grammar of the article reflects the time period when it was written. With cramped fingers, Tim Grayson shifted the tiller of the Snow Queen a fraction of an inch. Instantly the iceboat responded, veering across the hard black ice toward Lighthouse Point. Tim allowed himself one backward glance. Raleigh Bryan in the Penguin was close behind, with one leg of the race still to go. As the two ice yachts neared the southern side of the lighthouse, Tim prepared to make an extra tack to avoid a line of soft ice behind a small red marker. For a moment he was tempted not to go about. It was so cold that day that he didn’t see how there could be any soft ice left. The red marker had nothing to do with the race course; it was just a danger warning, Tim knew, and the extra tack would cost several seconds of precious time. But Tim’s conscience won, and in another minute he put his rudder hard alee to make the tack. When he came back on his original course he found the Penguin twenty yards ahead of him. Raleigh Bryan hadn't bothered about the red marker! In spite of the cold, little drops of sweat ran down Tim’s back as he shifted his position in the stern of the boat. He knew that his safety tack had cost him the race; but, as he saw it, there was nothing else to do. It wasn’t the risk to himself that had influenced Tim. He could swim in any water, and from the crowd on shore watching the race, many friends would have rushed instantly to haul him out. It was the Snow Queen that would have suffered had they gone through. Staved-in framework, warped rudder, ruined varnish —all threatened an iceboat that broke through the surface, and the Snow Queen belonged to Greg, Tim’s older brother. With all the skill at his command, Tim fought to regain the distance lost, but the Penguin held most of her lead. Tim realized that his last chance to win had vanished; and with this race went the opportunity to pilot the Snow Queen in the Navesink Yacht Club Regatta. Greg had told him he could sail in the Navesink contest if he took first place in one of the Shrewsbury (NJ) skeeter races. And this was the last race of the season. In another minute Raleigh had cut expertly across the line amid cheers from the crowd. “Nice work, Raleigh!” Tim shouted across the icy basin. Raleigh smiled his slow, confident smile. “You all would have trimmed me if you hadn’t been so scary about gettin’ your feet wet,” he drawled, as he led the way into the boat house, Tim never forgot the next half hour. Slowly came the amazing realization that the majority of the crowd thought him a coward. He found himself floundering in the knowledge of their contempt. “What’s the matter, Tim? Afraid of a cold bath?” Red Harris blurted out. “You'd have won that race if you hadn’t been such a, sissy about that soft-ice marker.” Tim’s mouth was still open when he heard Greg beside him. “There’s no use explaining,” Greg said quietly. “People either understand or they don’t. Everybody doesn’t feel the same way about a boat.” Tim looked up at his brother gratefully. At least Greg knew that he hadn’t been afraid of getting wet. “What I didn’t like,” Greg went on, “was the way you made the tack and then your attempts to shift your weight on the last leg.” In his slow, deliberate voice Greg analyzed every inch of the race until Tim fully understood his mistakes. Next day came a sudden thaw. Tim decided that it would be warm enough to work on the Snow Queen out of doors. Greg had suggested a few adjustments in the rigging, and his brother was anxious to carry them out. The thought of meeting people at the boat house so soon after losing the race was unpleasant, but Tim was glad to have something that forced him to get the ordeal over with. The boat house belonged to the township of Shrewsbury and served as a clubhouse for anyone interested in sailing. Usually a crowd collected early, but today the only person in sight was Red Harris. “Hello,” said Red. “Going out?” Tim shook his head. “Nope. Just got some repairs to make.” “This thaw may weaken the ice a bit, but even so I guess you'd be safe,” Red remarked significantly. “Raleigh’s out sailing.” He was just about to ask Red to help him carry in the Snow Queen when Red pointed to the spot where the Navesink River joined the Shrewsbury. “Look at that bird go!” he said, “Doesn’t care a whoop what he does!” Tim looked and could hardly believe his eyes. Raleigh Bryan’s Penguin was tearing ahead toward the place where the fishing lights had been. “It isn’t safe!” Tim gasped. “They were fishing through the ice up there last night, and it won't be properly frozen over.” “Don’t worry, Grandma,” Red’s voice was sarcastic. “Raleigh can take care of himself. He’ll probably jibe.” Tim watched the Penguin skudding along before the wind and a frown came between his eyes. “Listen, Raleigh hasn’t been up north very long and I’ll bet he’s never seen ice like that before. He probably doesn’t know how dangerous it is.” Red laughed and for a minute Tim hesitated. If he went after Raleigh, and the newcomer realized all the time what he was doing, he would be thought more of a mollycoddle than ever. But if he held back and Raleigh did not recognize the circles of thin ice, what then? As the Penguin kept straight on for the spotted ice, Tim grabbed a boat hook and flung it on board the Snow Queen. “You can laugh all you like,” he shouted back at Red Harris. “I’m going to stand by.” Hardly had his little boat got under way when the bow of the Penguin faltered in one of the thinly covered holes. In another instant came the sound of ripping ice and wood. The Penguin’s mast crumpled; her sail flapped and fell; half of her frame disappeared under water. Tim now could see Raleigh’s terrified face just above the water. He was fighting wildly against the current, handicapped by a tangle of rope and canvas. Working fast, Tim drew as near to the Penguin as he dared and spun her head into the wind. With a rattle of gear and rigging he dropped his sail. The Snow Queen still coasted forward and Tim frantically used one leg and the boat hook to check her speed. When she finally slithered to a standstill he was within thirty feet of Raleigh and the black pool of open water. Hurriedly casting off the painter, Tim threw one end of it to within a few inches of Raleigh’s shoulder. “Grab it!” he shouted, but Raleigh shook his head desperately. “I can’t!” he gasped. “My feet are caught and I’ve done something to my left arm. The current’s too strong. I tell you, I can’t let go.” Tim was already overboard, carrying the boat hook in one hand. “I’m coming,” he called reassuringly. But as he spoke the ice creaked threateningly beneath him. Dropping on his stomach, he began inching his way forward. When he came within a few feet of Raleigh the ice dipped under his weight, letting water ooze out over the surface to drench his chest and legs. Every second he expected the groaning ice would give way and throw him into the driving current. He could hear the rush of the water and could see that it was pushing the Penguin further under the ice. In another minute Raleigh would have to let go of her stern or be dragged under with it. In spite of wet hands, clumsy with cold, he fastened the painter around the end of the boat hook and thrust it toward Raleigh. “Stay just as you are,” he ordered, “I think I can get the rope round you. If I come any nearer, I'll break through.” “R-right,” Raleigh muttered from between blue lips. Maneuvering carefully with the boat hook, Tim finally looped the rope around Raleigh’s body. Once, as he drew it back, it slipped and started sliding snake-like toward the water. Tim reached for it with the hook and retrieved it just in time. “All set,” he shouted to Raleigh and began pulling on the rope; but instead of extricating the other pilot, he felt himself being drawn forward toward the open water. Unable to get a grip on the ice with his feet, Tim knew that continued pulling would only send him into the water. Casting about desperately for a solution of his difficulty, Tim thought of the Snow Queen. “Hold on,” he yelled, scrambling backward, “I’ll have you out pronto!” But he felt little of the confidence his words implied, for he could see that Raleigh was weakening fast and might be drawn under at any minute. Furiously Tim worked himself toward the ice boat. Trembling in his haste, he made the painter fast to a cleat at the stern. He knew he would now need every ounce of the skill Greg had tried to teach him. “Hang on to the rope with your good hand,” he shouted to Raleigh, “and when we begin to move try to kick clear.” Swiftly he shoved the Snow Queen’s bow in the direction he wanted to go and hoisted her sail. Then, hands grasping the boat, he ran alongside, pushing her forward. As he wind filled her sail, he jumped aboard. Would she start with Raleigh’s weight acting as an anchor? Would the drowning boy be able to kick himself free? Was the painter long enough to give them a chance? Tim looked back breathlessly. He moved the rudder lightly. “Go to it, Snow Queen!” he said under his breath. As if the little boat understood, she strained forward and Raleigh came sprawling across the ice like a gigantic fish. Just how he got him on board, Tim was never sure, but somehow he stopped the boat long enough to haul the half-frozen boy beside him. “How did—” Raleigh began, as Tim shoved him close to the center rail in the middle of the boat. “Don’t try to talk,” Tim snapped, his whole attention concentrated on getting the boat to shore, “Just hang to that safety rail with your good arm.” When they reached the basin in front of the boat house Greg was standing on the ice beside Red Harris, a pile of sails in his arms. “We—we—were just coming after you,” Red sputtered but Greg said nothing. Dropping the sailcloth, he reached a helping hand to Raleigh and half carried him toward the house. “Hurry up, Tim,” he ordered, “you've got to get on some dry clothes yourself.” “How about the Queen?” Tim began, but Red hastily interrupted. “l’ll put her up for you, Timmy,” he said. Relieved, Tim raced after Greg into the stuffy warmth of the boat house. In a few minutes Greg had Raleigh dressed in some old dungarees, a torn sweat shirt, and a heavy blanket that he’d found lying about. Around Raleigh’s bruised wrist he had fashioned a temporary bandage. In spite of the heat, Raleigh’s teeth were still chattering; but the color had come back to his lips and his cheeks no longer looked green. As he stuttered and stumbled through his story, Tim realized that it was exactly as he had surmised. Raleigh was practically on top of the newly frozen over fishing holes before he recognized the danger. Once in the water, his feet caught in the ropes and it was impossible for him to do more than keep himself afloat. “I still don’t see how you got across that ice,” he declared, turning to Tim, “It was the bravest thing I ever have seen!” “Tim’s never been accustomed to shy from danger,” Greg said dryly, as Red Harris poked his flaming head around the door to tell them that two men from the Navesink Yacht Club had succeeded in pulling the battered Penguin ashore. In about half an hour, the blood was coursing warmly through Raleigh’s veins and Greg thought it was safe to take him home. When they left him at his door he was still praising Tim’s bravery. “Well,” said Greg, as they drove off, “I guess that squelches any rumor about your losing yesterday’s race because you were afraid of a ducking. But what pleases me most, Timmy boy, is the way you handled the boat just now. You sailed her like a veteran! If you do anything like as well in the Navesink Yacht Club Race you ought to win it hands down!” Editor's Note: As mentioned in the 6/30/2023 blog, “Ice Yachting Winter Sailboats Hit More Than 100 m.p.h. by John A. Carroll, The Detroit Ice Yachting Club has fostered one of the more exclusive organizations in the world - the Hell Divers. To be eligible, a yachtsman merely has to take the plunge and survive to tell the story.” It appears that Raleigh became a Hell Diver by his harrowing experience. To learn more about the fishermen who created the circles on the ice, go to New York Heritage HRMM Commercial Fishermen oral histories here. Author"Circles on the Ice" by L. R. Davis and Illustrated by R. B. Pullen; "The Open Road for Boys" magazine February 1937. From the Ray Ruge Collection, Hudson River Maritime Museum. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's note: The following text is from articles printed in the New York City area newspapers in 1895 and 1920.. Thank you to Contributing Scholar Carl Mayer for finding, cataloging and transcribing this article. The language, spelling and grammar of the article reflects the time period when it was written. SPOONING PARTIES. How These Commendable Aids to Matrimony Should Be Conducted. “Spooning” parties are popular in some quarters. They take their name from a good old English word which was intended to ridicule the alleged fantastic actions of a young man or a young woman who is in love. For some reason, which no one ever could explain, everybody pokes fun at the lover. In fact, that unhappy character is never heroic in real life, no matter what great gobs of heroism are piled about him on the stage, and in all the romantic story books. The girl in love and the boy in love are said to be “spoony.” When a “spooning" party is given, the committee in charge of the event receives a spoon from each person who attends, or else presents each guest with a spoon. These spoons are fancifully dressed in male and female attire, and are mated either by the similarity of costume or by a distinguishing ribbon. The girls and boys whose spoons are mates are expected to take care of each other during the continuance of the social gathering. Of course the distribution of the spoons is made with the greatest possible carefulness, the aim being to so place them as to properly fit the case of the young people to whom they are presented. The parties are usually given by the young people of some neighborhood where the personal preference of each spoony is well known, and they are the source of no end of fun. It is possible also that they serve as aids to matrimony as well, and are therefore commendable, since an avowal is made more easy to a diffident swain after he feels that his passion is not a secret, but that his weakness for a ‘‘spoony'’ maiden is known to his friends and enemies on the committee which dispenses the spoons. It may be mentioned that after the spoons have been distributed among the guests, each couple retires for consultation regarding the reasons which caused the award of mated spoons in their case. This consultation is known by the name of "spooning.’’--St. Louis Republic .via The Yonkers Herald, June 24, 1895 High Cost of Living leads to loss of the Courting Parlor “Don't love in Gotham-- You've got no place to go; You can't hide in the subway Or on the roofs, you know! The cop that's on the corner Has got his eye on you-- Don't love in Gotham-- You'll be ‘pinched’ if you do!" SO sang Tom Masson—or, in words to that effect—some ten years ago, but the tragi-comic warning is just ten times as true this summer. For one of the problems of 1920 in merry old Manhattan is the H. C. of L., which in this connection should be translated the High Cost of Loving! Cupid knows it always has been a dilemma for New Yorkers. In all the side streets, east or west, there isn’t a piazza with rambler roses curtaining it and a hammock swung across one comer, there isn't a circular seat built around a drooping elm or broad spreading maple, there isn't a lovers' lane or a Ben Bolt “nook by a cool running brook.” No got. No can do. But now courting must be conducted between the devil of the profiteering landlord and the deep sea of propriety. For the simple truth is that almost no New Yorker can afford have a parlor for his daughter's beaux, that daughter herself can't find a house with a parlor in it, if she ls boarding. The rent laws passed at Albany do not prevent anybody from ejecting Cupid. And he is quite literally put out on the sidewalk—or into the park. The easiest way for the “new poor” —the thousands with stationary salaries—to pay their rent is simply to let an outsider pay rent for that extra room, once the courting parlor. The tenements long ago learned to use the “roomer" to cope with the landlord. The flats and apartments are profiting by the lesson. As for the boarding-house landladies, who can blame those harassed women for filing every room under their roofs to help pay the butcher and the baker? President Hibben of Princeton was complaining recently about the frankness and lack of reserve between the young men and women of to-day, but even these candid souls have not reached the point where they'll do their courting in the bosom of their families. If the parlor and solitude a deux is not for them, then neither is the family living room! Hence it is that there never were so many spooners in Central Park as there are to-day—I mean to-night. Every bench is a kissing bench. And the rush is such that two loving couples often are forced to seek accommodations on the same bench! Not even the rain drives them off. When it pours too hard they simply seek refuge in the tunnels. The Park cops are being worn out by their job as civic chaperones [sic]; the Park squirrels, from being interested, and then shocked, are now merely bored. And the deep sea of propriety is much vexed. “How can nice girls make love so publicly!” indignantly exclaim the old maids of either sex. "Nothing like that goes with us," declares the Hudson River Day Line, or, to quote exactly its recent announcement, “All spooning is tabooed from the decks of the boats. We request that the conduct of the young people shall be above criticism. The young women can help largely to control the situation.” Maybe they can—if they take Mr. Masson's advice and "don't love in Gotham.” But if a nice young clerk is so ill advised as to fall in love with a nice young stenographer, will you tell me just how they can do their courting? He can't “say it with flowers.” Theatre tickets, candy—nice candy. There articles are in the luxury class, nowadays, even for ardent lovers. She has no parlor in which she can receive him. They can't afford to go to a decent restaurant and buy enough lemonades, after dinner, to give them the privilege of spending the evening there. There remain the park, the seat on top of the bus, the Coney Island boat —public enough, heaven knows, but at least populated by strangers and not by a too observant family. There is also the sapient scheme of the rookie who took his girl to the Pennsylvania Station, rushed to the gate with her when a train was announced, bade her a fond, an osculatory farewell—then sneaked back to the waiting room and encored the performance when the gates were opened for the next departing train and the next and the next! Who knows but the much criticized cheek-to-check dancing is not merely a pathetic attempt to make love in the face of a cold and hostile world? “Romance is dead, but all unseen romance jazzed up at nine-fifteen, to paraphrase Mr. Kipling. But don't let anybody think he has solved the housing problem until he brings back the beau parlor or gives us a just-as-good substitute. From the New York Evening World, July 14, 1920 DAY LINE TABOOS SPOONING - Hudson Boats to Have Community Song Services. Beginning yesterday, “spooning" was tabooed on the boats of the Hudson River Day Line. Thousands of circulars will be distributed today setting forth the new "directions" of Ebon E. Olcott, the President. "We have said many times that some share of the comfort and enjoyment of the Sunday boat rides rests with each and every one on board.” says the circular. "Will you help us make the memory of these trips wholesome and full of enjoyment? We request that the conduct of the young people shall be above criticism. ... ." There will be a "community service" on the boats each Sunday and a religious service at Pavilion No. 2, at Bear Mountain. From The New York Times, June 13, 1920. Find a summary of this topic here. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor’s Note: The following text is a verbatim transcription of an article featuring stories by Captain William O. Benson (1911-1986). Beginning in 1971, Benson, a retired tugboat captain, reminisced about his 40 years on the Hudson River in a regular column for the Kingston (NY) Freeman’s Sunday Tempo magazine. Captain Benson's articles were compiled and transcribed by HRMM volunteer Carl Mayer. This article was originally published December 30, 1973. Fog, that natural phenomenon so prevalent on the river in the fall and spring when the seasons change, has constantly been a problem to boatmen. Obviously, there is always the danger of collision or grounding. Today, the electronic marvel of radar has done much to lessen the danger of the boatmen’s old foe. Prior to World War II, however, there was no radar. Then, the boatmen had nothing to rely upon except their boat’s compass, the echo of their boat’s whistle off the river bank, and their own knowledge of the river with all its tricks of tide, wind and twisting-channels. Few people on shore, unless they at one time had worked on the river, ever realized how extensive and uncanny this knowledge was. Years ago, probably the best men on the river in fog were the captains and pilots of the Cornell Steamboat Company’s big tugboats - the tugs that pulled the big tows of that era, sometimes with as many as 50 or 60 barges and scows in a tow. They had to be good. A steamboat pilot could almost always anchor. But on the big tugs, when the fog would close in with the tide underfoot with a big tow strung out astern and no room to round up and head into the tide, they had no choice but to keep going. One time, back around 1930, there was a company in New York harbor that specialized in the towing of oil barges. Their tugs would push oil barges up the Hudson River and through the New York Barge Canal to cities like Utica, Syracuse and Buffalo. One day one of their tugboats was pushing an oil barge up the river, destined for Buffalo, when off Tarrytown it began to get very foggy. At the time they were overtaking a big Cornell tow in charge of the tug "J. C. Hartt.” As the fog was getting thicker, the captain of the small tug pushing the oil barge went up to the tail end of the Cornell tow and put a line from the oil barge on to the last barge in the ‘‘Hartt’s” tow. He held on until the fog cleared up near Bear Mountain and then let go and went on his way. About two weeks later, when the canal tug and its oil barge got back to New York, the tug captain’s boss came down to the dock and said, “Cap, were you holding on a Cornell tow about two weeks ago?” The tug captain was sort of flustered and sputtered, "Why, why when?” “Well,” replied the boss, “we've got a bill from Cornell here for $65 for towing from Tarrytown to Bear Mountain,” and he then mentioned the times and the date. The oil barge tug’s captain knew his boss had the goods on him, so all he could say was, “Yes, that’s right. I was caught in fog off Tarrytown when they were going by. And you know those Cornell men know the river in fog better than anybody. I knew I'd be safe hanging on and sailing along with them. The boss said, “Well, I guess we'll have to pay it, but don't do it again.” I am sure many other canal tugs did the same thing, some getting away with it and some not. As they used to say along the river, the men on Cornell's steady pullers were the best compasses on the river. Now, those able boatmen, men like Ira Cooper, Al Hamilton, Ben Hoff, Sr., Jim Monahan, John Sheehan, Jim Dee, Albert Van Woert, John Cullen, Dan McDonald, Barney McGooey, Larry Gibbons, Howard Palmatier and a host of others, have long since steered their last tugboat through a fog. And those big, powerful steady pullers, tugboats like the “J. C. Hartt,” “Geo. W. Washburn,” "John H. Cordts,” “Edwin H. Mead,” “Pocahontas,” “Osceola” and “Perseverance” have all towed their final flotilla of scows and barges. Gone forever are the big tugboats with their red and yellow paneled deck houses and towering black smokestacks with their chrome yellow bases. The only thing that remains constant is the River with its changing tides. And the fogs of spring and autumn. AuthorCaptain William Odell Benson was a life-long resident of Sleightsburgh, N.Y., where he was born on March 17, 1911, the son of the late Albert and Ida Olson Benson. He served as captain of Callanan Company tugs including Peter Callanan, and Callanan No. 1 and was an early member of the Hudson River Maritime Museum. He retained, and shared, lifelong memories of incidents and anecdotes along the Hudson River. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's Note: This article, "'Companionship and a Little Fun': Investigating Working Women’s Leisure Aboard a Hudson River Steamboat, July 1919," written by Austin Gallas and published in Lateral 11.2 (2022). https://csalateral.org/issue/11-2/companionship-and-a-little-fun-investigating-working-women-leisure-hudson-river-steamboat-1919-gallas/#:~:text=The%20investigator's%20written%20account%20offers,Hudson%2C%20and%20how%20Progressive%20reformers Article Abstract: This article provides an in-depth consideration of a single report penned on the night of July 27, 1919 by a private detective employed by New York City's Committee of Fourteen (1905-1932), an influential anti-vice and police reform organization. A close reading of the undercover sleuth's account, which details his experiences, subjective judgments, and general observations regarding moral and social conditions while aboard the "Benjamin B. Odell", a palatial Hudson River steamboat enables us to enrich our grasp of the courtship and pleasure-seeking practices popular among working women and men active in New York City's heterosocial and largely segregated amusement landscape during the so-called "Red Summer". Specifically, the report reveals how wage-earning women articulated femininity and sought individual freedoms, companionship, pleasure and romance via Hudson River steamboat excursions. AuthorAustin Gallas recently earned a PhD in Cultural Studies from George Mason University, where he currently teaches in the Department of Communication. His dissertation is titled "Value of Surveillance: Private Policing, Bourgeois Reform, and Sexual Commerce in Turn-of-the-Century New York." Austin's current research interests include undercover surveillance in New York City history, Progressive Era urban police reform, American literary journalism during prohibition, and the sexual and gender politics of the American minimum wage debate of the 1910s. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

|

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 [email protected] Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |