History Blog

|

|

|

|

|

The Hudson River Maritime Museum has an extensive collection of oral histories interview of Hudson River commercial fisherman, including fisherman Edward Hatzmann, who was interviewed on April 25, 1992. Below, Hatzmann recalls a story told to him by fellow fisherman Charlie Rohr, about a prison break from Sing Sing Prison in Ossining, New York.

Unlike some fishermen's tales, this one was really true! Fisherman Charlie Rohr really did have to deal with the prisoners. He was interviewed for the Yonkers, NY Herald Statesman in an article published April 14, 1941. The article is transcribed in full below:

"'We're Going To Bump You Off!' Killers Promise Charlie Rohr. But Shad Fisherman, Who Rowed Fugitives Across Hudson, Talks Them Out of It and Escapes Alive" OSSINING - Charlie Rohr is alive today, but from now on he feels he's living on borrowed time. Rohr is the shad fisherman who rowed two desperate escaped convicts across the Hudson River and then talked himself out of being their third victim. "It was pretty tough sitting there with two guys holding guns to you," Rohr reported, "but it didn't do any good to lose your head." Rohr and another fisherman were getting their equipment together in their shack shortly before 3 A.M., preparatory to rowing out to their weirs. A series of shots broke the pre-dawn stillness but the men didn't pay much attention to it. "I thought it was just a brawl," Rohr said. The other fisherman went upstairs for a minute, and Rohr stepped to the door of the shack on Holden's Dock. Two men, white-shirted and in the gray trousers unmistakably of Sing Sing Prison, confronted him. Two guns were held against his stomach. "Is this your boat?" one growled. "Yes," said Rohr. "Get going then," he was told. "And fast - we've just killed a cop." Rohr wasn't having any. "You take the boat," he urged. "You're rowing," he was told. "Get going." The trip across the river took an hour - the longest hour of Charles Rohr's life. The thugs sat in the center and stern seats of the boat, and trained their guns upon him during the entire trip. Rohr worked the oars, and then men whispered back and forth. The fisherman pulled up at a point near Rockland Lake on the west bank. The convicts prepared to leave the boat. "Now," said one in an expressionless voice, "we're going to bump you off." "Listen," said Charlie Rohr, his mind working faster than it ever had before, "that won't do you no good." The men paused. "I'm well known around here, see? Everyone knows my boat. And if you knock me off, and the boat's around here, everyone is going to know what happened and where you guys got away." They were still listening, so Rohr kept on. "What you'd better do is let me go back. Then no one's going to know anything about this." Four eyes regarded him coldly. Then the pair whispered together for a minute. Charlie Rohr held his breath, and then his heart leaped. The men jumped from the boat and ran into the woods on the shore of Rockland County. He rowed back across the river with shaking knees.

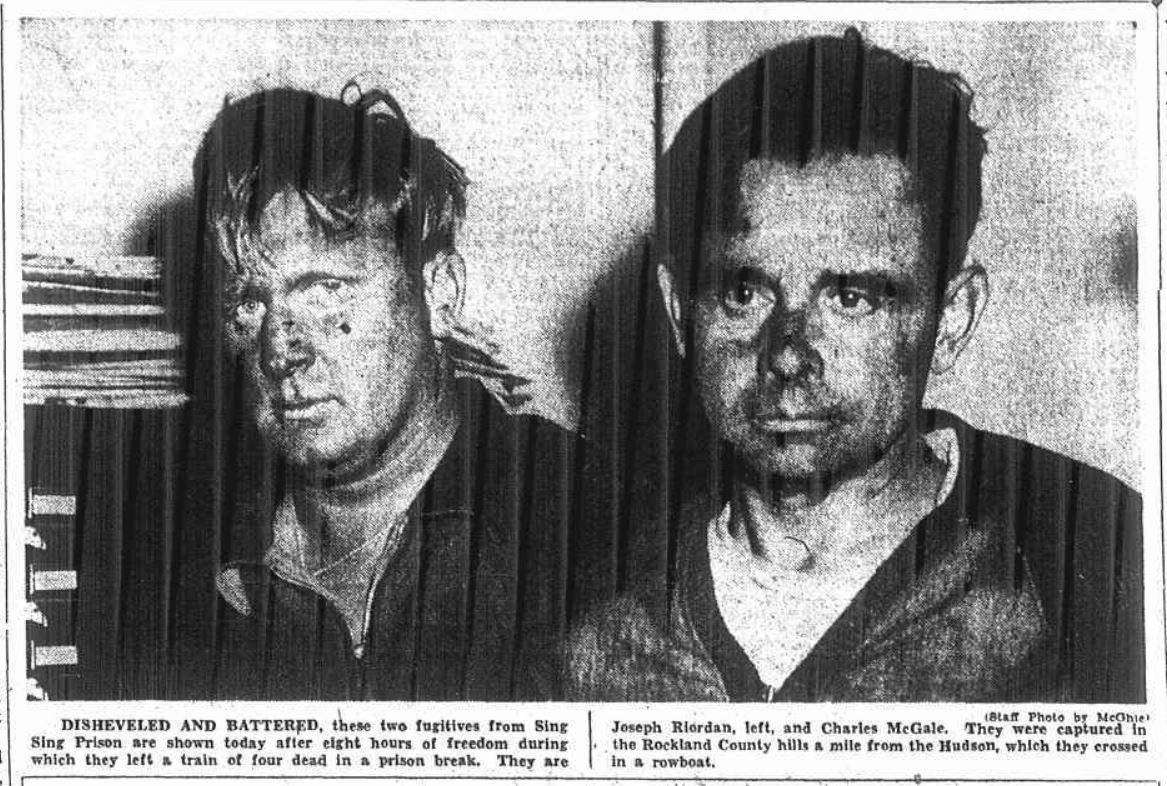

"Disheveled at battered, these two fugitives from Sing Sing prison are shown today after eight hours of freedom during which they left a train of four dead in a prison break. They are Joseph Riordan, left, and Charles McGale. They were captured in the Rockland County hills a mile from the Hudson, which they crossed in a rowboat." caption of photograph from Yonkers "Herald Statesman" front page, April 14, 1941.

Joseph Riordan and Charles McGale were caught in Rockland County and returned to prison. Charlie Rohr went back to fishing.

If you'd like to hear more stories from Edward Hatzmann, check out his full oral history interview, available on New York Heritage. For more fishermen's oral history interviews, check out our full collection.

If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

0 Comments

Today's Media Monday post features Frank LoBuono/Sojourner Productions circa 1990 Shad Fishing the Hudson feature for "Metro Magazine". Hudson River Maritime Museum thanks Frank LoBuono/Sojourner Productions for allowing us to share this video. "Since the beginning of time, in early Spring, the Shad have made their annual trek from the ocean to the fresh waters of the upper Hudson River to spawn. And, for centuries before Europeans set foot on this continent, the Native Americans were on the banks of the Hudson to harvest them. Eventually, Europeans replaced the Native Americans throughout the region. However, they continued the tradition of harvesting the Shad every Spring. In fact, at one point, there were hundreds of small shad boats fishing the river, from Fort Lee, NJ to Poughkeepsie, NY. They took them by the thousands to be sold mostly at fine Manhattan restaurants. Many of these boats were operated by families who passed the tradition down through generations. People forget that in the 1970’s the Hudson nearly died from the ravages of pollution. It became unsafe to eat fish taken from the river. This decimated the industry and most of the boats disappeared. Eventually, the EPA cleaned up the river to the point that it was safe once again to harvest SOME fish, including the shad. One of the families that had made a tradition of fishing for shad were the Gabrielson’s of Nyack. The father and son team returned to the Hudson year after year to claim their prize. It was backbreaking work, but they wouldn’t miss it for anything. TKR Cables “Eye On Rockland” decided to feature the shad fishing Gabrielson family and their time on the Hudson as Spring returned to the river. This is their story." Click on the button to listen to more Hudson River Commercial Fishermen Oral Histories. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

We are into shad season now, so we thought we'd share more stories from our Hudson River Commercial Fishermen oral history collection!

Today's story comes from Port Ewen commercial fisherman George Clark, talking about growing up fishing with his father Hugh Clark, and an encounter with a fish market dealer who tried to get the better of them.

If you'd like to see Hugh Clark's original shad boat, it is on display at the Hudson River Maritime Museum toward the back of our East Gallery in the boat slings. To listen to all of George Clark's oral history interview, visit New York Heritage.

If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor’s Note: The following text is a verbatim transcription of an article featuring stories by Captain William O. Benson (1911-1986). Beginning in 1971, Benson, a retired tugboat captain, reminisced about his 40 years on the Hudson River in a regular column for the Kingston (NY) Freeman’s Sunday Tempo magazine. Captain Benson's articles were compiled and transcribed by HRMM volunteer Carl Mayer. See more of Captain Benson’s articles here. This article was originally published May 6, 1973. For many decades in years past, one of the true harbingers of spring locally was the annual run of shad in the Hudson River. The shad fishermen would lay their nets and, to many residents, the first shad was a happy event. Generally, the relations between boatmen and the shad fishermen were amicable. The shad nets wound frequently drift across the channel and the boatmen would do their best to avoid them. On occasion, however, due to conditions of tide and wind - the boatmen would have no recourse but to run over the nets. Then, the relationship would be somewhat strained. At times the results were not without a touch of humor and, at other times, a bit bizarre. One time back in the, 1920's the tug "Victoria" of the Cornell Steamboat Company was going down river with several loaded scows for New York. She was bucking a flood tide off Highland and shaping the tow up for the cantilever span of the railroad bridge. The pilot on watch was getting close to the [b]ridge when he noticed he was going to run over a shad net. On looking over to the Highland side of the river, he saw a row boat coming out with an outboard motor and two men in it. Obviously they were the shad fishermen. He quickly blew one short blast on the whistle for the deckhand to come to the pilot house. When the deckhand came up, the pilot said, "Here, watch her, I’ve got to go below for a minute." Going down to the main deck, he went to the galley and put on the cook’s apron and hat and stood in the galley door as the shad fishermen came alongside. When they were within shouting distance, one of the fishermen hollered over, "What the devil are you running over my nets for?” and added a few more choice words of admonition. Of course, the deckhand in the pilot house didn’t know what to say since he was a new man and green at the game. The pilot, dressed like the cook, stood in the galley and laughed at the poor deckhand taking the bawling out. Then, to add insult to injury, he looked at [t]he fishermen, shaking his head and pointing up at the pilot house — as if he was in sympathy with the fishermen and perhaps not thinking much of the “pilot” steering the tugboat. On another occasion shortly after World War I, the steamboat "Trojan" of the Albany Night Line was on her way down river and, when off Glasco at about 11 p.m., ran over some fisherman's shad net. The fisherman yelled up to the pilot house of the passing steamer from his rowboat, "The next time you do that, I'll shoot you." About a week later as the "Trojan” was coming down past Crugers Island, a shad net was again stretched across the channel. Due to the nature of the channel at that point and the way the tide was running, the pilot bad no alternative but to run over the net. All of a sudden, [a] fellow in the rowboat stood up and fired a shot in the direction of the "Trojan." Fortunately, the shot missed the pilot house, but did hit the forward smokestack, putting a small hole in it. The later incident was related to me by the late Dick Howard Jr. of Rensselaer who was quartermaster on the “Trojan” at the time. Actually a sidewheeler, like the "Trojan,” would do little damage to a shad net by running over it. Despite their size, the side-wheelers were of exceptionally shallow draft and almost always would pass right over the net itself suspended beneath the surface. The only damage would be to have a couple of the net's surface floats clipped off by the turning paddle wheels. A propeller driven vessel, on the other hand, with its deeper draft, could do considerable damage to a shad net by snagging it and chewing up part of it by the revolving screw propeller. Most boatmen though, whenever possible, when passing over a shad net - would stop their boat’s engine and drift over it so as to avoid damaging the net. AuthorCaptain William Odell Benson was a life-long resident of Sleightsburgh, N.Y., where he was born on March 17, 1911, the son of the late Albert and Ida Olson Benson. He served as captain of Callanan Company tugs including Peter Callanan, and Callanan No. 1 and was an early member of the Hudson River Maritime Museum. He retained, and shared, lifelong memories of incidents and anecdotes along the Hudson River. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Are your shad bushes blooming? The large shadbush (also known as juneberry or serviceberry or shad blow) in the museum's courtyard is getting ready to bloom - that means the shad run is starting!

In this story, Port Ewen commercial fisherman Frank Parslow describes restrictions on fishing in New York Harbor during WWII and the impact on Hudson River fishermen. This audio clip is part of the Hudson River Maritime Museum's Hudson River Commercial Fishermen Oral History Collection. You can listen to a selection of the museum's full oral history interviews on New York Heritage.

If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Today's Featured Artifact is an eel pot used by Hudson River commercial fishermen. The wire pot contains a series of cones which allow the eels to enter the trap, but make it difficult or impossible to leave. The wooden pegs used as closures on this eel pot were carved by Hudson River commercial fisherman Henry Gourdine. Eel fishing was once a major industry in the Hudson River. British food traditions include eel pie and jellied eel, smoked eel is considered a delicacy in most Eastern European and Scandinavian countries, and Japan, Korea, and Vietnam also enjoy eel in a wide variety of foods. In the mid-20th century, eel was a major export from the Hudson River fishery. American eel are opposite of many Hudson River fish in that they live in the river, and only return to the ocean to spawn. All American eels (and over 30 other species of eel) are born in the Sargasso Sea off the Atlantic coast of Florida and the Caribbean. The tiny new hatchlings ride the Gulf Stream north along the Atlantic coast in search of fresh water. By the time they reach the Hudson River, they are known as "glass eels," for their tiny, transparent bodies. American eel can take between 12 and 20 years to reach maturity, at which point they return to the Sargasso sea to lay and fertilize eggs. This lengthy period of maturity means fewer eels survive to reproduce. In addition, the damming of tributaries, habitat loss, pollution, and overfishing contributed to their precipitous decline in the 1980s. The exact life cycle of all species of eel and the reason for their decline remains largely a mystery, although more research is being conducted every year. Today, American Eels are endangered and fishing for them in the Hudson River, and elsewhere, is no longer allowed. It may take decades for the population to recover. Thankfully, in 2008 the NYS Department of Environmental Conservation started the Hudson River Eel Project, in which volunteers work with DEC scientists and educators to count glass eels and help transport them over obstacles to access freshwater tributaries in the Hudson Valley. To learn more about the project, check out the video below! If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Filmmaker Ken Sargeant has compiled many of Henry's stories, including with footage from a filmed oral history interview, into "Tales from Henry's Hudson." In 2013, Arts Westchester put together this short video of Henry, combining oral histories from the Hudson River Maritime Museum and film interviews by Ken Sargeant. You can watch more of Henry on film below: For today's Media Monday, we thought we'd highlight one of the best storytellers on the Hudson River. Henry Gourdine, a commercial fisherman on the Hudson River since the 1920s, was a famous advocate for the river and its fishing heritage. Born on Croton Point on January 7, 1903, his reminiscences of growing up along the waterfront, defying his mother to spend time there, and his working life on the river, captured the imagination of the region at a time when commercial fishing was under threat from PCBs. A boatbuilder, net knitter, and fisherman, as well as a storyteller, Gourdine helped preserve many of the fishing crafts. He taught boatbuilding and net knitting at South Street Seaport, recorded descriptions of many heritage fishing methods on tape, and would happily talk about the river and fishing to anyone who asked. Henry Gourdine passed away October 17, 1997 at the age of 94. Read his New York Times obituary. In 2006, the New York Times published a retrospective on the impact of Henry Gourdine on local communities throughout the valley. Henry Gourdine on FilmHenry Gourdine Oral HistoryThe Hudson River Maritime Museum has an extensive collection of oral history recordings of Hudson River commercial fishermen. Marguerite Holloway interviewed Henry Gourdine several times between 1989 and 1994, covering a whole host of fishing-related topics. Those oral histories now reside at the Hudson River Maritime Museum and have been digitized for your listening and research pleasure. Click the button below to take a listen! Henry Gourdine's Fishing ShackBuilt in 1927, Henry Gourdine's fishing shed stood for decades along the Ossining waterfront. But the days of the working waterfront were over, and Ossining sold the property to developers in the early 2000s. By 2006, work was set to begin, and Henry's shed was not part of the for condominiums overlooked the Hudson River. Despite pleas from local conservationists and the Gourdine family, including a temporary injunction from a court, the shed was ultimately demolished in May, 2006. Henry's fishing equipment and two boats were salvaged from inside and saved by Arts Westchester and family members. Preservationist and cataloger of ruins Rob Yasinsac cataloged the shed and its contents in April, 2006, before it was bulldozed. Read his account and see more pictures. Sadly, the development soon stalled, and ground was not broken on the condos until 2014. Henry Gourdine ParkPerhaps as an apology for the demolition, the condominium development known as Harbor Square created a waterfront park and named it Henry Gourdine Park in honor of the man who fished off its shores for nearly 80 years. The park was opened in June, 2018. You can learn more about the park and its amenities and visit yourself. Recorded in the summer of 1976 in Woodstock, NY Fifty Sail on Newburgh Bay: Hudson Valley Songs Old & New was released in October of that year. Designed to be a booster for the replica sloop Clearwater, as well as to tap into the national interest in history thanks to the bicentennial, the album includes a mixture of traditional songs and new songs. This album is a recording to songs relating to the Hudson River, which played a major role in the commercial life and early history of New York State, including the Revolutionary War. Folk singer Ed Renehan (born 1956), who was a member of the board of the Clearwater, sings and plays guitar along with Pete Seeger. William Gekle, who wrote the lyrics for five of the songs, also wrote the liner notes, which detail the context of each song and provide the lyrics. This booklet designed and the commentary written by William Gekle who also wrote the lyrics for: Fifty Sail, Moon in the Pear Tree, The Phoenix and the Rose, Old Ben and Sally B., and The Burning of Kingston. Pete Seeger wrote a song for a friend, Ron Ingold, a shad fisherman on the Hudson River. Ingold is one of the new breed of Hudson River fishermen who is ready to fight for the environmental health of the River and, since he is on the River almost daily, he understands the importance of that delicate balance that must be maintained between Man and Nature. He understands this far better than the “half-blind scholars” who scarcely know which way the wind is blowing or which way the currents are flowing. https://folkways-media.si.edu/liner_notes/folkways/FW05257.pdf Editor's Note: Hear interviews with Ron Ingold and other Hudson River commercial fishermen here: https://nyheritage.org/collections/oral-histories-hudson-river-commercial-fishermen OF TIME AND RIVERS FLOWING - LYRICS Of time and rivers flowing The seasons make a song And we who live beside her Still try to sing along Of rivers, fish, and men, And the season’s still a’coming When she’ll run clear again. So many homeless sailors, So many winds that blow, I ask the half-blind scholars Which way the currents flow. So cast your nets below And the gods of moving waters Will tell us all they know. The circles of the planets, The circles of the moon, The circles of the atoms All play a marching tune And we who would join in Can stand aside no longer Now let us all begin! Thanks to HRMM volunteer Mark Heller for sharing his knowledge of Hudson River music history for this series. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

If ever a man loved a river, Robert Hamilton Boyle Jr. loved the Hudson — and he was not afraid to shout his love from the rooftops. In his classic text, The Hudson River: a Natural and Unnatural History (1969), Boyle makes his feelings abundantly clear with the book’s very first line. “To those who know it,” wrote Boyle, “the Hudson River is the most beautiful, messed up, productive, ignored and surprising piece of water on the face of the earth. There is no other river quite like it, and for some persons, myself included, no other river will do. The Hudson is the river.” Gratifyingly, Boyle’s love for the Hudson was not merely a historic/scientific scholarly interest. Yes, Boyle studied the Hudson obsessively, but he did more than passively analyze his favorite waterway. He actively fought to save the river in its darkest hour, when pollution had reduced the Hudson to a shell of its former self. In his decades-long conservationist crusade, Boyle wrote watershed exposes, discovered crucial legal strategies, and founded a seminal environmental organization. Not bad for blue-collar “Brooklyn-born sportswriter and angler.” By the end of his life, Boyle — the down-to-earth fisherman — had become “the unofficial guardian of the Hudson River.” All that being said, a question remains. How did Boyle come to be so fascinated by the Hudson River? Why did he want to save it so badly? By all accounts, Bob Boyle grew to love the Hudson during his 1940s boyhood boarding school years, when he spent his days off fishing by the (then relatively clean) riverside. When he moved to Croton-on-Hudson in 1960, Boyle was treated to a rude awakening. Instead of the semi-healthy river of his youth, Boyle found a waterway this close to clinically dead. Pollution, of both chemical and human waste varieties, had progressed to intolerable levels. In addition to being a health hazard to humans, the river’s once abundant flora and fauna were mysteriously dying out. Boyle, ever the fisherman, would not stand for that sort of thing. He decided to take up arms and go to war for the Hudson. His weapon of choice? A pen. To reiterate an old cliché, a picture is worth a thousand words. Bob Boyle clearly took that message to heart. In his historic 1965 Sports Illustrated article, “A Stink of Dead Stripers,” Boyle began with a simple command: “Take a good look at the picture below.” The picture in question revealed a thousand-strong pile of striped bass “left to rot” at a dump. Even without context, a discarded fish-kill of that size looked, well, fishy. Bob Boyle thought so too — and he knew just who to blame. The culprit, in Boyle’s (ultimately correct) opinion, was the Consolidated Edison Company. The exact circumstances of the kill were not exactly clear — “but the fish apparently were attracted by warm water discharged from the plant and then were trapped beneath a dock.” Concerned citizens took pictures of these massive fish kills and submitted them to the New York State Conservation Department — which later “denied that such pictures existed” when questioned by Boyle. Of course, Boyle did eventually manage to get ahold of those pictures. Their publication, in conjunction with the scathing Sports Illustrated article, was the opening salvo in Boyle’s war against Consolidated Edison. From the start, one fact was crystal clear: Boyle wasn’t going to pull any punches. In 1962, Consolidated Edison announced plans for a new hydroelectric power station, plans which had local fisherman and conservationists up in arms. The company hoped to carve a facility out of Storm King Mountain, a site renowned for its scenic beauty. Locals were, understandably, a little horrified by this scheme. The proposed power plant would obviously mar the landscape — and it probably wouldn’t do the river’s fish population much good either. Bob Boyle suspected that Con Ed’s “water-intake equipment would kill small fish,” decimating the population of his beloved striped bass. In 1965, Boyle joined a number of conservation groups (including Scenic Hudson, one of New York’s most enduring non-for-profit organizations) in a “lawsuit against a proposed Consolidated Edison power plant.” It was not an easy fight, but, after many years of legal battle, the conservationists’ efforts bore fruit. The lawsuit, entitled Scenic Hudson Preservation Conference v. Federal Power Commission, resulted in “the first federal court ruling affirming the right of citizens to mount challenges on the basis of potential harm to aesthetic, recreational or conservational values as well as tangible economic injury.” It was, in every respect, a game changer and the true beginning of the modern environmental movement. And what was the crucial keystone of Scenic Hudson’s case? Scientific studies on the Hudson’s striped bass population, which would have, as Boyle predicted, been decimated by Con Ed’s plant. After the Battle of Storm King had been won, Boyle did not choose to sit back and bask in his victory. No, he knew that work still had to be done. The river remained a polluted mess. By preventing the creation of Con Ed’s power plant, Boyle had only fulfilled the physician’s doctrine: “First, do no harm.” The Hudson still needed a thorough cleaning and a dedicated protector, a watchdog to scare the polluters away. To that end, Boyle began to conceive of a plan. He imagined a sort of ‘river keeper,’ a naturalist/conservationist “out on the river the length of the year.” This riverkeeper would keep watch on the river, sniffing out polluters and bringing them to task. What’s more, the riverkeeper would not act alone. They would have an entire organization behind them — an organization with real teeth. Boyle already had already founded just such an organization, the Hudson River Fishermen’s Association, in 1966. In 1983, the Fishermen’s Association evolved into ‘Riverkeeper,’ a non-for-profit environmental organization dedicated to the protection of the Hudson. But what about the organization’s aforementioned teeth? Well, Boyle had discovered, years earlier, a pair of 19th century laws (the Rivers and Harbors Act of 1899 and the New York Harbor Act of 1888) which banned the “release of pollutants in the nation’s (and the state’s) waterways.” Furthermore, the two Acts allowed “citizens to sue polluters and collect a bounty.” Luckily, the laws still held in the modern era. Bob Boyle and the Fishermen’s Association tested out their legal strategy against the Penn Central Railroad, and were able to stop a “pipe spewing oil from the Croton Rail Yard” and collect “$2,000 in fines, the first bounty awarded under the 19th-century law.” The bounty money was then repurposed to underwrite suits against other polluters. Riverkeeper wisely kept this legal strategy. All in all, it was an admirably self-sustaining system. Eventually, Riverkeeper evolved past the Hudson River. It became a model for others around the world, a part of the “Waterkeeper alliance.” Today, the Waterkeeper organization “unites more than 300 Waterkeeper Organizations and Affiliates that are on the front lines of the global water crisis, patrolling and protecting more than 2.5 million square miles of rivers, lakes and coastal waterways on six continents.”14 The individual waterkeepers work with local communities, enforce environmental laws, track down polluters and educate children about the environment. They are watchful protectors, just as Bob Boyle intended. Although his main contribution to the environmental movement was undoubtedly Riverkeeper, Boyle never gave up and grew tired of his favorite river. He certainly never gave up fishing for his beloved striped bass. After all, Boyle is the man who once wrote: “There may be more stripers in the Hudson than there are people in New York State. I often find this a cheering thought.” Boyle was, in life and in print, down-to-earth, passionate, and adventurous — with a wryly sardonic sense of humor. He lived a life rich in meaning, a life he could be proud of. Case in point: Boyle once predicted that the Hudson would become “either ‘clean and wholesome’ or ‘bereft of the larger forms of life.’” Before he died on May 19th, 2017, Robert H. Boyle could be sure of two things: 1) the river had “gone the better way” and 2) he had played a small but crucial part in its salvation. It just goes to show. Everyone is capable of making a difference, if they only have the courage to try AuthorLucia O’Corozine is a student at Hampshire College. She was an Education and Research Intern with the Hudson River Maritime Museum over the summer of 2018 and contributed research to HRMM’s new exhibit, “Rescuing the River: 50 Years of Environmental Activism on the Hudson.” This article was originally published in the 2019 issue of the Pilot Log. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor’s Note: The following text is a verbatim transcription of an article featuring stories by Captain William O. Benson (1911-1986). Beginning in 1971, Benson, a retired tugboat captain, reminisced about his 40 years on the Hudson River in a regular column for the Kingston (NY) Freeman’s Sunday Tempo magazine. Captain Benson's articles were compiled and transcribed by HRMM volunteer Carl Mayer. See more of Captain Benson’s articles here. This article was originally published April 30, 1972. In the days when the Hudson River was relatively pollution free, every spring shad fisherman could be found with their nets from New York City north to Castleton. Shad fishermen would frequently venture far from home, going to a spot on the river that was particularly to their liking and there set up their operation. One of these was Bernard “Nod'' Washburn of Sleightsburgh. When I was a boy, "Nod" Washburn was a neighbor of ours. He was then an old man. and would fascinate me with the recounting of his shad fishing experiences. “Nod” also impressed me as a boy with an expression he would use when something especially caught his fancy. He would say, “By the handle of the great horned spoon!,’’ an expression I never heard anyone else use. In the 1880's, 1890's and the early years of this century, “Nod" and his father always fished for the spring run of shad at Cranston’s, later known as Highland Falls. The steamboat landing at that point was then known as Cranston’s after the large hotel then located there. The hotel later became what is now Ladycliff Academy, just south of Highland Falls village. A Portable Shanty With the coming of spring, “Nod” and his father would load their round bottom shad boat with nets, floats, supplies and a portable shanty to live in. They would then leave Sleightsburgh and row over to the Romer and Tremper steamboat dock at Rondout. There, their boat and gear would be hauled aboard either the “William F. Romer" or the “James W. Baldwin.” Leaving Rondout at 6 p.m., they would then sail down the river, as the old timers would say, on the “night boat.” On the way down river, the Washburns would sleep right in their shad boat that was being carried on the freight deck. Being known by the crew, they would have their supper down in the crew's mess room. “Nod" told me he always preferred to go down on the “Romer” because he knew the steward, Henry Bell, would always give them a good supper. In return, the Washburns always saw to it that Steward Bell and his family received their share of fresh shad for the season. They would arrive at Cranston's about 2 a.m. in the lonely morning hours, after making all the landings between Rondout and Highland Falls. "Nod" said they couldn't get much sleep because at every landing there would be the noise of loading freight, the rumble of the hand freight trucks, and the mate hollering at the freight handlers to hurry up so the steamer could get away on time. Leaving the ‘Romer’ After the “Romer” left the dock at Cranston’s, she would pull out in the river and stop, swing out her forward davits, lower the Washburn's boat and all its gear in the river, and then continue on her way to New York City. "Nod" and his father would then row over to Boat House Point on the east shore, pick out a good location and set up their shanty. They would then get their fishing gear ready "to get on the make" with the first flood tide. If the tide was right, they would make their first drift at about 8 or 10 a.m. Sometimes they missed the first flood tide, and after getting things all set, would be so tired they would sleep until late morning. They camped and fished off Highland Falls yearly from about the first of April until Memorial Day. On nights when the Washburns had shad to ship to New York, they would raise a red lantern to let either William Mabie, the pilot on the “Romer" or Abram Brooks, the pilot on the "Baldwin” know there would be shad to be put aboard the steamer. When put on the steamboat, the shad were packed in long boxes filled with ice on the freight deck, and the mate would see to it they were well taken care of. “Nod" and his father preferred the Romer" as their friend "Billy" Mabie[,] the pilot, would always drop a copy of the Kingston Daily Freeman in their boat to be read when drifting with their nets on the flood and ebb tides. When the steamboat reached New York, a representative of the New York markets would meet the boat at the Franklyn Street pier and buy the shad. The mate Henry Kellerman of the “Romer" or the mate of the “Baldwin" did all the financial transactions in the big city. When the steamboat came back up the next night, the fishermen would have to be over at the dock at Cranston's to collect their money, which was always right to the penny. Then they would settle their account with the mate. ‘True Blue’ Mate Washburn said never once was anything written on paper. Everything was left to the honesty of the mate. Always he was ‘‘true blue," as a boatman would say. As spring wore on and it came to the latter part of May, changes would come to the river. The south wind of summer would begin to blow up through the Highlands, bringing with it the smoke from the chemical works at Manitou; the “Mary Powell” would commence her daily runs to New York; the mosquito[e]s would rise from the marshes in back of Conn's Hook; the water would start to get warm and the shad would start to get soft. One morning, “Nod" Washburn's father would say, "Well 'Nod', who comes up tonight?” “Nod" would answer, "Well, Pop, it’s the ‘Romer,’ she went down last night." His dad would say, "We are going to get her up tonight. I’m getting homesick for Sleightsburgh. When I get aboard, I am going up in the pilot house and shoot the breeze with ‘Billy’ Mabie and find out all that we missed since we've been away from Sleightsburgh and Port Ewen. When we get home tomorrow, I can sleep all day." Back in Rondout When their boat was put off the "Romer" in Rondout Creek, the Washburns would just row across the creek to the shore by the old sleigh factory that used to be east of the shipyard, pull their boat up on shore, and go up the hill to their home and go to sleep. Then, later, they would go back down, unload their boat, and put their shad nets away for another season. Back in those days, "Nod" said you could leave your boat down on shore with all supplies in it and nobody would touch a thing — even if it sat there for a week. So ended another long ago day of shad fishing in the lordly Hudson. AuthorCaptain William Odell Benson was a life-long resident of Sleightsburgh, N.Y., where he was born on March 17, 1911, the son of the late Albert and Ida Olson Benson. He served as captain of Callanan Company tugs including Peter Callanan, and Callanan No. 1 and was an early member of the Hudson River Maritime Museum. He retained, and shared, lifelong memories of incidents and anecdotes along the Hudson River. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

|

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 [email protected] Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |