History Blog

|

|

|

|

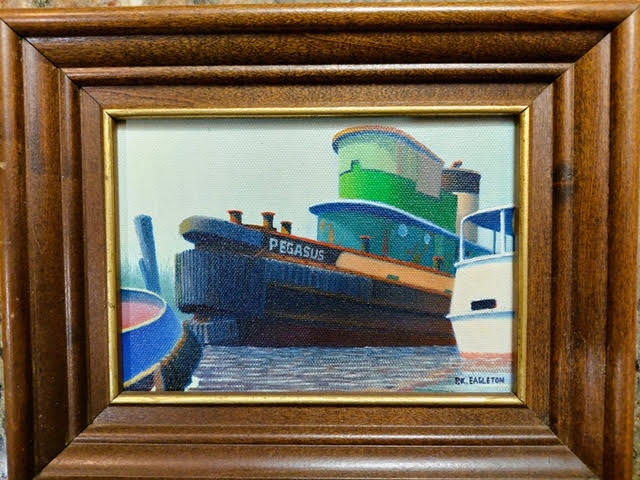

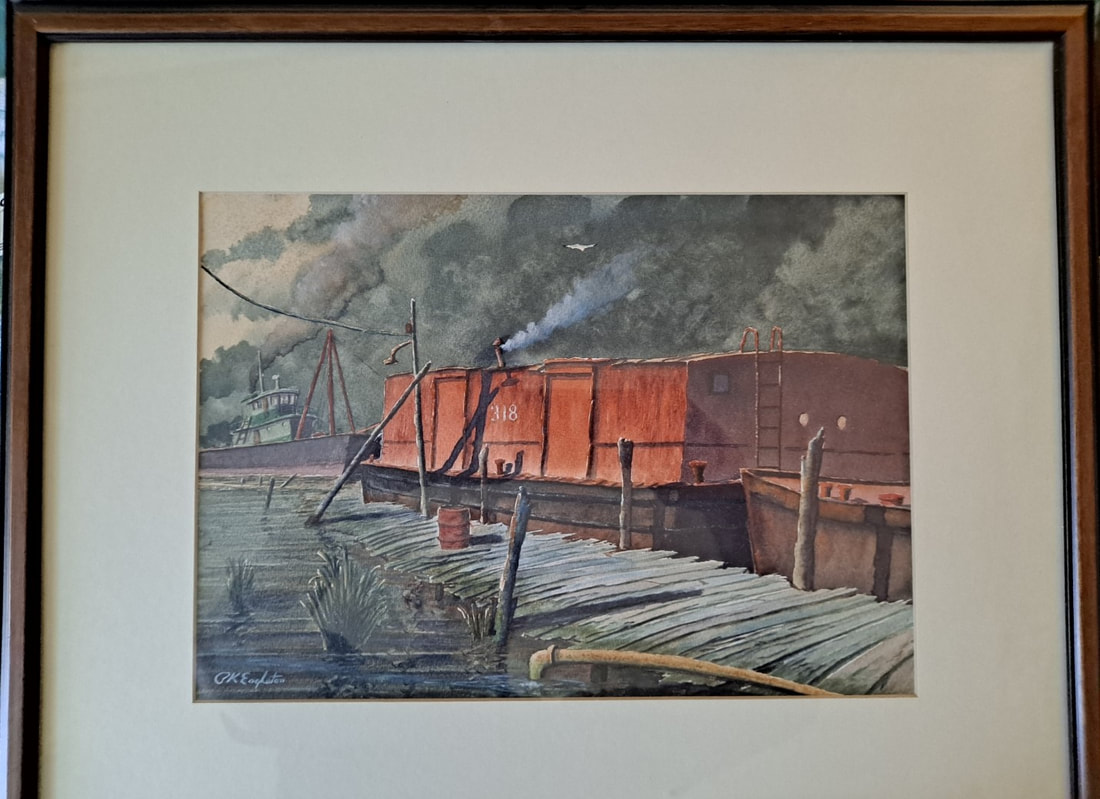

The tug Pegasus was built in 1907 as the Standard Oil Co. No. 16 and served waterside refineries and terminals of Standard Oil. When McAllister acquired her in 1953, her original steam engine was replaced with diesel. Pamela Hepburn of Hepburn Marine Incorporated bought her in 1987 to tow oil barges and railroad car-floats, along with other transport work, and it was then that she was renamed Pegasus. Retired in 1997 after a 90-year career, she underwent extensive restoration work to serve as a training vessel and museum, and it is from this time period (c. 2000) that she is depicted in Eagleton’s painting. Although Pegasus was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2001 as part of a preservation initiative, she was unfortunately scrapped in 2021. Hudson River Maritime Museum are thrilled to announce a brand new exhibition, Working Waterfronts, displaying oil and pastel paintings by Hudson Valley maritime artist, Peter K. Eagleton. Working Waterfronts will open to the public on May 17 and be on display in the museum’s East Gallery through December 22, 2024. The late Peter K. Eagleton (1937-2005) was an accomplished artist of marine subjects and marine historian. He was familiar with ships, tugboats, docks, and yards, encountering them, regularly during his career as a shipbroker. His strikingly vibrant and carefully composed paintings celebrate the world of working waterfronts and the graceful shapes of freighters, tugs, ships, lighters, yard oilers, and tankers that plied the waters of New York Harbor and the Hudson River. About Peter K. Eagleton (1937-2005) Born in Yonkers, New York, Mr. Eagleton was an accomplished artist and marine historian. He worked for over 36 years in the steamship business as a shipbroker in New York and Scandinavia. He also served on a panel for the U.S. government negotiating trade rates with Asia. His memberships included the Salmagundi Club, The American Society of Marine Artists, the National Maritime Historical Society of America and the Edward Hopper Foundation, as well as an Official U.S. Coast Guard Artist. Eagleton also served for six years as a sergeant in the National Guard. His work was recognized by the Coast Guard’s George Gray Award for outstanding artistic achievement and his paintings appear in a number of significant marine art collections, including the National Coast Guard Museum, the American Merchant Marine Museum, the Mystic Seaport Museum, and the Intrepid Museum.  A red railroad barge lies against a deteriorating wooden pier outside of Edgewater, New Jersey, located just south of the George Washington Bridge. This type of vessel is known as a “lighter,” a flat-bottomed barge that transfers goods between moored ships in the harbor and a railroad terminus on shore. There were as many as 1000 of these covered barges operating in New York Harbor by 1950, and they were referred to collectively as the “Railroad Navy” since most were owned by the railroad companies with terminals in the greater New York area. Vessels like this one collected along Edgewater Flats, muddy shoals just north of the town, as waterfront industry declined in the second half of the 20th century. From 1994 through 1995, the Army Corps of Engineers engaged in a large project to clear more than 100 decommissioned and abandoned barges from the flats. Although the vessels may not have been operational, some were still used for a variety of purposes. The Knickerbocker Canoe Club, established in 1880, held monthly meetings aboard a steel barge on the flats and used two wooden barge hulks to store their gear. The New York Motorboat Club used two other barges nearby. Similarly, the barge pictured here has outlived its heyday as a working vessel, but smoke emanates from the chimney, indicating that someone still benefits from the warmth of the stove inside. The huge majority of these barges were surrendered and scrapped when the Army Corps of Engineers ordered the users to either refloat or lose the vessels. Two prominent examples of covered railroad barges have survived into the 21st century: Lehigh Valley No. 79 (1914), which now serves as the Waterfront Museum in Red Hook, Brooklyn, and the Pennsylvania Railroad No. 399 (1942), privately owned here on the Rondout Creek in Kingston. Peter Eagleton’s paintings focus on the sometimes-unglamorous work boats of New York Harbor and the Hudson River: tugboats, barges, tankers, and ferries, all working to transport cargo and people from place to place. In the spirit of American Realism, the movement that began in literature in the late 19th century and in visual arts in the early 20th century, Eagleton chooses these everyday images of working waterfronts as the unconventional subjects of his art, finding beauty amidst the rust. Just as Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks famously offers a glimpse into the late-night scene of a diner with its three customers and singular server, as if the viewer of the painting is just walking past, Eagleton’s paintings act as a window into the often-overlooked world of marine transportation, scenes we pass daily as we drive over Hudson River bridges or down Abeel Street right here in Kingston. These paintings invite us to pause and consider these scenes not only as the unseen cogs in the commerce that powers our daily lives, but as aesthetic subjects in their own right. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

0 Comments

On April 10, 1912, New York marine artist Samuel Ward Stanton was waiting to board the RMS Titanic. A prolific artist and chronicler of American steamboats, he had spent the previous months traveling in Europe, researching and preparing sketches of the Alhambra and other Spanish scenes associated with author Washington Irving. He had intended to use these in his commission to design and decorate some of the interiors of the new Hudson River Day Line steamboat named Washington Irving, the largest of the Day Line “Flyers” ever built. Stanton was likely thrilled to board the new and sensational RMS Titanic at Cherbourg with muralist Francis Davis Millet for her inaugural voyage to New York. One imagines he may have prepared a drawing or two of her majestic bow and her opulent interiors before packing them in a portfolio crammed full of European scenes. Samuel Ward Stanton was born in Newburgh in 1870 to Samuel Stanton and Margaret Fuller. Samuel Sr. was a principal of the Ward, Stanton & Company shipyard which was created out of the bankrupt Washington Iron Works at the foot of Washington St. in 1872. Before failing, the iron works had produced naval machinery, steam engines, boilers, sawmills and sugar mills. The new company continued to produce machinery but grew to emphasize iron shipbuilding. Samuel Ward Stanton grew up in and around the yard observing the scene and becoming a talent with pencil and pen. He also assembled scrapbooks detailing steamboats and their histories which became important sources for the articles and books he published as a young man. In 1884, the family moved to Florida aboard a small, iron sidewheel steamboat they built for themselves. The steamboat included the machinery for a sawmill, which was assembled upon arrival and put to immediate use in building a house and presumably selling lumber to other newcomers. The yard in Newburgh later became the famous T.S. Marvel Co. shipyard. As an adult, “Ward” Stanton, as he was known to his friends, returned to New York and developed a distinctive pen and ink style that emphasized the details of the ships and boats that he documented. He became acquainted with New York marine artist James Bard (1815-1897) who became a friend and an important source of information for those boats no longer available for direct observation. He later provided financial assistance to Bard’s daughter Ellen out of deep respect for the late pioneering steamboat painter. Stanton earned a bronze medal at the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893 for his collection of Erie Canal drawings and in 1895 published his seminal American Steam Vessels, the first in a series of illustrated books by Stanton illustrating the history of steam navigation. He wrote and produced illustrations for periodicals including Seaboard Magazine, Marine Journal and the Nautical Gazette and his illustrations appeared in other books on steam navigation and regional history. He began producing murals and promotional art for the Hudson River Day Line, notably a series of car cards advertising the line’s “flyers.” Stanton painted a series of steamboat history scenes for the 1909 Robert Fulton and was active in the 1909 Hudson Fulton Celebration. He also prepared art for the Catskill Evening Line and the Nantasket Beach Steamboat Co. As Stanton boarded the RMS Titanic with Francis David Millet, he could never have imagined the disaster that lay ahead of him. Just four days later, on the evening of April 14, 1912, the Titanic struck an iceberg, and by the early morning of April 15, had sunk. Stanton was not among the survivors. He was just 42 years old. What happened in his last hours remains unknown, and his European work in all likelihood perished with him. One account indicates that a black coat bearing a letter inscribed “W. anton” was recovered in Canada and sent to his wife Cornelia. Sadly, the sinking of the Titanic meant that Samuel Ward Stanton never returned to New York to finish his work for the Washington Irving - it was completed in 1913 with references to Irving’s tales including the Alhambra reading room completed by other artists. Although his tragic death often overshadowed his talents, thousands of drawings and paintings produced and published before his trip to Europe remained, continuing to inspire the marine artists and students of steamboating that followed in his wake. AuthorMark Peckham is a trustee of the Hudson River Maritime Museum and a retiree from the New York State Division for Historic Preservation. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Major Henry Livingston, Jr. (1744-1828) went with his cousin's husband, Major General Richard Montgomery, on the 1775 invasion of Canada. These were short term enlistments, so he became major of the 3rd NY in August and returned home in late December. The diary is shown along with the Hudson River School's images of the terrain. The music was transcribed from Henry Livingston's handwritten music manuscript, one of the largest such books of the period. The Journal of Major Henry Livingston of the Third New York Continental Line, August to December, 1775. [edited] By Gaillard Hunt, Washington, D.C. Compiled and created by Mary Van Deusen. http://www.henrylivingston.com/writing/prose/revdiary.htm Thanks to HRMM volunteer Mark Heller for sharing his knowledge of Hudson River music history for this series. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

|

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 [email protected] Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |