History Blog

|

|

|

|

Detail of still from early documentary film, first shown publicly in 1912. In the foreground is a killer whale (Orcinus orca) named Old Tom, swimming alongside a whaling boat that is being towed by a harpooned whale (out of frame to the right). A whale calf can be seen between Old Tom and the boat. The whalers were based in Eden, New South Wales, Australia. Wikimedia Commons. This week, we're going a bit afield of the Hudson River for Media Monday. Our November 3rd lecture, "The Orca-Human Bond: The True Story behind The Whaler’s Daughter" with author Jerry Mikorenda, covered the amazing history of cooperation between killer whales (orcas) and Indigenous people (and later European whalers) in Australia. We'll have the lecture video up on our YouTube channel soon (some of our fall lectures are already up!), but in the meantime, you can enjoy this excerpt from the 2004 Australian documentary film, "Killers in Eden." Author Jerry Mikorenda said this documentary film was one of the inspirations for his YA novel, Whaler's Daughter. We've previously discussed whaling in Australia with the song "The Wellerman." Whaling in Two-fold Bay Australia was particularly special because of a unique pod of orcas that assisted human whalers with capturing migrating baleen whales. The "Law of the Tongue" was that the orcas would get first dibs on the baleen whale carcasses, preferring to eat only the lips and the tongue. The human whalers could then haul the rest of the carcass ashore to harvest the blubber for whale oil and other products. Sadly, as whaling continued, other more commercial whaling companies were less open to the idea of cooperating with the whales, and by the 20th century the pod had disappeared. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

0 Comments

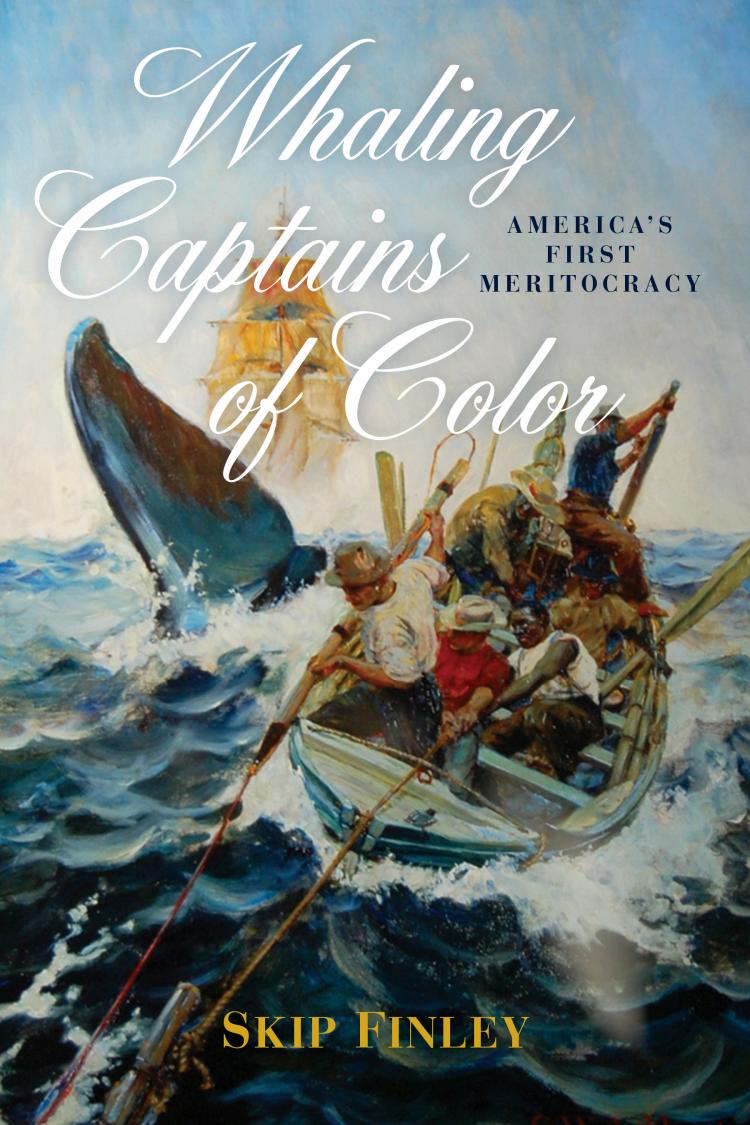

"Whaling Captains of Color: America's First Meritocracy" book cover: Clifford Ashley, Lancing a Sperm Whale, 1906. Like Herman Melville, Clifford Warren Ashley (1881 – 1947) an American artist, author, sailor, and knot expert took a whaling trip aboard the Sunbeam in 1904. Of the 39 crew all except 8 were black. He wrote “The Blubber Hunters”, a two-part article in Harper’s Magazine about the trip. The original oil painting hangs in the New Bedford Free Public Library. In this recent lecture for the Southampton History Museum, author and historian Skip Finley discusses his research from his new book Whaling Captains of Color: America's First Meritocracy (June, 2020). Many of the historic houses that decorate Skip Finley’s native Martha’s Vineyard were originally built by whaling captains. Whether in his village of Oak Bluffs, on the Island of Nantucket where whaling burgeoned, or in New Bedford, which became the City of Light thanks to whale oil, these magnificent homes testify to the money made from whaling. In terms of oil, the triangle connecting Martha’s Vineyard to these areas and Eastern Long Island was the Middle East of its day. Whale wealth was astronomical, and endures in the form of land trusts, roads, hotels, docks, businesses, homes, churches and parks. Whaling revenues were invested into railroads and the textile industry. Millions of whales died in the 200-plus-year enterprise, with more than 2,700 ships built for chasing, killing and processing them. Whaling was the first American industry to exhibit any diversity, and the proportion of men of color people who participated was amazingly high. A man got to be captain not because he was white or well connected, but because he knew how to kill a whale. Along the way he would also learn navigation and how to read and write. Whaling presented a tantalizing alternative to mainland life. Working with archival records at whaling museums, in libraries, from private archives and studying hundreds of books and thesis, Finley culls the best stories from the lives of over 50 Whaling Captains of Color to share the story of America's First Meritocracy. You may have seen sea shanties in the news lately. CNN has talked about them. And NPR. Our friends at SeaHistory did a lovely writeup, too. For some reason, these historic maritime songs have struck a chord with folks around the world. Shanties may have started their modern revival with the 2019 film, Fishermen's Friends, based on a true story about a group of Cornish fishermen whose work song chorus catapulted them to unexpected stardom in the UK. The film became available to American audiences via streaming giant Netflix in 2020. Sea songs and shanties are two different things, according to experts interviewed by JSTOR daily and Insider.com. Shanties are work songs, often designed for call-and-response. Sea songs are those about the sea, but not designed to be sung while at work. Both evoke a bygone era the lends itself to romanticism, even as the real life experience was less than ideal. "The Wellerman" and ShantytokSo why "The Wellerman" and why did Shantytok become a thing? Scottish postal worker Nathan Evans (he's since quit his job with a record deal in hand) posted a video of his acapella version of "The Wellerman," a 19th century New Zealand whaling song to TikTok with the hashtag #seashanty on December 27, 2020. Kept home by the pandemic lockdown, along with many other people around the world, Evans' version went viral. The next day, Philadelphia teenager Luke Taylor used TikTok's duet feature to add a harmonizing bass line to Evans' video. That version, too, went viral, and other TikTok users from around the world kept adding harmonies and instrumentals to build on Evans' original song. "The Wellerman," also known as "Soon May the Wellerman Come," is a song based in real life. Joseph Weller was a wealthy Englishman suffering from tuberculosis. A doctor recommended a sea voyage, and Weller and his family found their way to Australia in 1830. The next year, they purchased a barque and established a whaling station in nearby New Zealand - likely without the permission of the local Maori, who raided the station several times. The Wellers persisted until Joseph died in 1834. His sons continued whaling for several years, but sold out in 1840 and returned to Sydney. In later years the station also doubled as a general store supplying other whaling ships as well as their own. When the Wellers sold out, the station continued as a general store. So from the chorus of the song the lines, "Soon may the Wellerman come and bring us sugar and tea and rum" are likely a direct reference to the Weller family store supplying whaling ships. Read more about the history of "The Wellerman" and a biography of the Wellers. Unlike the sort of whaling practiced in Nantucket and made famous by Moby Dick (fun fact - Herman Melville actually worked on a Weller whaling ship), whaling in New Zealand in the 1830s was done from shore and was developed in response to declining sperm whale populations (learn more about shore-based whaling). Maori people in New Zealand also practiced whaling, and the crews of whaling vessels and stations were likely racially and ethnically diverse. Edward Weller himself married a Maori woman (learn more about Maori whaling traditions and the Weller connection). "The Wellerman" LyricsThe above version of "The Wellerman" is by the Irish Rovers and was filmed in 1977 aboard a sailing ship off of New Zealand. 1. There was a ship that put to sea, The name of the ship was the Billy of Tea The winds blew up, her bow dipped down, O blow, my bully boys, blow. Chorus: Soon may the Wellerman come And bring us sugar and tea and rum. One day, when the tonguin' is done, We'll take our leave and go. 2. She had not been two weeks from shore When down on her a right whale bore. The captain called all hands and swore He'd take that whale in tow. 3. Before the boat had hit the water The whale's tail came up and caught her. All hands to the side, harpooned and fought her When she dived down below. 4. No line was cut, no whale was freed; The Captain's mind was not of greed, But he belonged to the whaleman's creed; She took the ship in tow. 5. For forty days, or even more, The line went slack, then tight once more. All boats were lost (there were only four) But still the whale did go. 6. As far as I've heard, the fight's still on; The line's not cut and the whale's not gone. The Wellerman makes his regular call To encourage the Captain, crew, and all. Shanty v. ChanteyYou may have seen it spelled "chantey" or "chanteys" before, based on the French word "chanter" meaning "to sing" or "chantez" meaning "Let's sing" (both pronounced "shawn-tay"). Although most dictionaries now agree that the "correct" spelling is "shanty," "chantey" has held on in many American communities. Perhaps to differentiate it from the waterfront shack also known as a "shanty?" (that word also derives from the French - this time the French-Canadian "chantier," meaning a lumber camp shack). Or perhaps because Americans are more likely to adopt foreign words wholesale into the lexicon. Any way you spell it, chantey, chanty, shanty, or shantey - all are technically correct. The African Connection ORIGINAL CAPTION: "At the bow of the boat were gathered the negro deck-hands, who were singing a parting song. A most picturesque group they formed, and worthy the graphic pencil of Johnson or Gerome. The leader, a stalwart negro, stood upon the capstan shouting the solo part of the song, the words of which I could not make out, although I drew very near; but they were answered by his companions in stentorian tones at first, and then, as the refrain of the song fell into the lower part of the register, the response was changed into a sad chant in mournful minor key." Illustration from “Down the Mississippi” by George Ward Nichols, Harper’s New Monthly Magazine 41 (246) (November 1870). Some have questioned whether the reference in "The Wellerman" to "bring us sugar and tea and rum" was a reference to slavery. But given that "The Wellerman" is set in New Zealand, it was far more likely that the reference was about delivering sailors' rations, rather than a direct connection to slavery. However, sea shanties do have a direct connection to Africa and slavery. Call and response style work songs were common in West Africa, where many people were captured and sold into slavery for hundreds of years. Enslaved people brought these work song traditions with them when they were forced into labor in the Americas. Slaves worked in fishing, on sailing ships, and even on steamboats. Slaves who loaded and unloaded steamboats often sang a style of work song that came to be known as "roustabout" songs. When combined with dance, this song style was known as "coonjine" (learn more). Singing was one way that enslaved people could push back against the brutal domination of enslavers. Some references even indicate that Black and enslaved people themselves were once called "chanteys," reflective of their singing talents. New York singer and historian Vienna Carroll (who we've featured before), has also helps preserve New York's Black maritime history through song. Her version of "Shallow Brown" recounts an enslaved man, Shallow Brown, being sold away from his wife to work on a whaling ship in the North. Whaling in particular offered opportunities for free Black sailors and whalers in the United States. As whaling shifted to the Pacific and the Arctic, Black mariners were able to escape the harsher racism of the Caribbean and the American South. You can learn more about enslaved and free Black mariners in a previous blog post by historian Craig Marin. As anyone who has ever tried to raise a sail knows, singing "Haul Away Joe" can help you work in tandem with others. Keeping a rhythm helps with hauling, rowing, pulling in nets, loading cargoes, and any other heavy task that requires more than one person to work in rhythm with another. Singing also keeps the mind occupied, but focused on the task at hand. The West African call-and-response style became integral to shanties and was quickly adopted and adapted by sailors of all ethnicities. Sources & Further ReadingShanties:

New Zealand Whaling and The Wellers:

Black Mariners and Shanties:

Editor's Note: This article originally appeared in the Hudson River Maritime Museum's 2017 issue of the Pilot Log. “. . .with the smell of clover from the river banks came the pungent odor of whale oil, mixed with the salty tang of the ships which sailed up from the sea.” --Edouard Stackpole, Sea-Hunters (1953)  19th Century brass whale oil lamp. Library of Congress. 19th Century brass whale oil lamp. Library of Congress. The first great wave of economic expansion gripped the new American nation within twenty-five years after the ratification of the U. S. Constitution, at first with the creation of new municipalities and a flurry in turnpike building that opened the interior’s vast farming potential to the river corridor. This was quickly followed by a burst in industrial growth and a new sense of civic improvements in the riverfront towns in the emerging manifest destiny spirit. Some of the new ideas were not new at all, except in the novelty of their application here in the Hudson River Valley. Whaling was one of them. The industry already had a curious history in a New England-based community that was established at Hudson (called Claverack Landing until 1785) by Seth and Thomas Jenkins, Quaker brothers from Nantucket, an island in the Atlantic Ocean that was terrorized by the British during the American Revolution. Providence, Martha’s Vineyard and Newport were also represented among the thirty heads of families who created the new town—a city, even—that by 1786 had twenty-five whaling vessels, more than in all of New York city. Four years later and rapidly growing, Hudson was designated a United States port of entry because it stood at the head of ocean-going navigation whenever sand bars prevented river access to Albany. In 1797, one ship, the American Hero, brought in the largest cargo of sperm whale oil in American history. Hudson was a cosmopolitan port in these heady times, its trade including (much like today) exotic tapestries, Chinaware, English Staffordshire, French mahogany furniture—and visitors like the exiled French foreign minister Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord, who stopped while en route to a visit with a French marquise living near Schenectady, to examine the making of sperm oil candles and view an exhibition of Thomas Jenkins paintings.[1] The city remained vibrant even after the whaling industry collapsed with the War of 1812. Whaling was revived briefly in Hudson in 1829, when a new Hudson Whaling Company was attempted (not involving any of the original proprietor families). The industry also moved south as the Hudson River continue to be viewed as an amenable venue despite the extra time it took to come upriver. In fact, the river was also visited by whales, most famously in 1652 when a sperm whale (the world’s largest of the species) became stranded and died at Cohoes Falls, yielding spermacetti oil that made the best candles that local residents had ever had—and a horrific smell in its putrefaction for miles around.[2] The Jenkins brothers had first looked at Poughkeepsie before opting for Claverack Landing, but it was not until 1832 that an industry was established in Poughkeepsie, and in Newburgh, also involving Nantucket and New Bedford whalers but this time as crew, not proprietors. The Newburgh Whaling Company was established by an act of the New York state legislature on January 24, 1832, and, like the Poughkeepsie Whaling Company (created March 20), involved prominent businessmen desiring high civic accomplishments as well as profits. U. S. exports of sperm oil rose from 3,944 barrels in 1815 to more than 110,000 by 1831, leading the Poughkeepsie investors to expect as much as $6 million in profits in a scant four years. By April, 1832, the Newburgh company purchased and outfitted the Portland for $15,250, added the Russel ($14,500) in August, and the Illinois ($12,000) in 1833—but each made only two voyages. Their future looked promising—the Portland brought in 2,100 barrels of oil and 19,000 pounds of whalebone for $40,000 in sales on its last voyage—but the industry collapsed due to falling oil prices.[3] In Poughkeepsie, the new corporation raised $200,000 in stock sales within six weeks after incorporating, and a vessel (the Vermont) was purchased and sailed by the end of October. A second ship, the Siros, sailed in April of 1833, and the Elbe left that August. A second enterprise, the Dutchess Whaling Company, was formed under newly elected U. S. Senator Nathanial P. Tallmadge that fall, and also worked with a New Bedford agent. They bought ten acres on the riverfront and leased half of it to the Poughkeepsie company. Both good and bad news followed. The Vermont was spotted by a New Bedford ship off Cape Horn, South America, heading for Peru, but the Siroc was wrecked off Cape Good Hope (Africa). Another Dutchess ship, the New England, sailed in July of 1834 and by October had killed two whales in the Azores. The Vermont returned in early 1835 with $16,000 in whale oil, having traveled around the world, losing its captain in a stabbing incident probably involving one of his sailors. On its second voyage, the New England returned with $50,000 in cargo. Another ship, the Newark, returned also full and to great applause, and the Nathanial P. Tallmadge was launched in 1836. The bottom fell out of the market when the price of whale oil dropped in half as a result of a new, more severe panic that gripped the nation in 1837, the result of Andrew Jackson’s misguided banking policies. By 1841, when the Elbe lay wrecked in New Zealand, ships were being sold on their return. The Dutchess Whaling Company lost money in the sale of its land and went into receivership in 1848.[4] Politics played against the whalers in the clash of Democrat and Whig philosophies. Senator Tallmadge was roundly criticized by the Locofoco faction of Democrats as the tide of public opinion turned against the whole notion of speculation. A new technology was emerging, the use of gas in home and industry lighting, that would survive until the electrification era almost a century later. These local industries were too small to sustain profits amidst the vicissitudes of a changing market and the crew requirements that they faced. They had to hire expensive New England mariners because no one on the Hudson had the experience of ocean voyages. Richard Henry Dana, author of the classic whaling account Two Years before the Mast, a crew member with a New Bedford whaler that met the New England at sea, remarked about a “pretty raw” Poughkeepsie youth who was “just out of the bush” and knew nothing about sailing. The great promise at the beginning of the whaling industry on the Hudson River resulted from the size of the fleet and experience of the Hudson proprietors, but the industry in general just did not have the time to mature here. Like plank roads, Hudson River whaling passed into oblivion as another great idea of the antebellum era lost in the shuffle of “a go-ahead people”—as Poughkeepsie investor Matthew Vassar (in both whaling and plank roads) described his fellow Americans—whose future lay in a newer and much broader economy to come. [1] Vernon Benjamin, The History of the Hudson River Valley: From Wilderness to the Civil War (New York, 2014), 260; David Levine, “Hudson Valley Whaling Industry: A History of Claverack Landing (Hudson), NY,” in Hudson Valley Magazine, March 19, 2012 (http://www.hvmag.com/Hudson-Valley-Magazine/April-2012/Hudson-Valley-Whaling-Industry-A-History-of-Claverack-Landing-Hudson-NY/); Anna R. Bradbury, “The Rule of the Proprietors 1783-1810,” in History of the City of Hudson, New York . . . (Hudson, 1908; http://www.cchsny.org/uploads/3/2/1/7/32173371/-whaling_lesson_for_pdf.pdf); Du Pin Gouvernet, Henriette Lucie Dillion, Marquise de (ed. & tr. By Walter Geer), Recollections of the Revolution and the Empire. . . . New York, 1928 (1857?). [2] Adriaen van der Donck, A Description of New Netherland (tr. Jeremiah Johnson, ed. Thomas F. O’Donnell), Syracuse, 1968 (1655). [3] Patricia Argiro, “Whaling—A Short Lived Venture in Newburgh,” in Orange County Free Press (July 11, 1972); Mary McTamany, “Whaling Ships once anchored at First Street,” Mid-Hudson Times, March 7, 2007. [4] Sandra Truxtun Smith, A History of the Whaling Industry in Poughkeepsie, N. Y., 1830-1845. Vassar College thesis, Poughkeepsie, May 2, 1956. AuthorVernon Benjamin is the author of The History of the Hudson River Valley: From Wilderness to the Civil War and The History of the Hudson Valley: From Civil War to Modern Times. |

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 [email protected] Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |