History Blog

|

|

|

|

|

Editor's note: The following text is from the "Kingston Daily Freeman" newspaper September 16, 1905. Thank you to Contributing Scholar George A. Thompson for finding and cataloging this article. The language, spelling and grammar of the article reflects the time period when it was written. BRICKYARDS OF KINGSTON AS DESCRIBED BY THE BUILDING TRADES EMPLOYERS ASSOCIATION BULLETIN. In its "Story of Brick" on the Hudson river, yards of Kingston and vicinity are described by the Building Trade Employers' Association Bulletin as follows: The brick which bears the highly popular brand, "Shultz," is the product of the Shultz yards at East Kingston, near Rondout, N. Y. Henry H. Shultz, the present manager of the concern for the Shultz estate, represents the third generation of a family which has been in the brick making business since the earlier half of the last century. At that period Charles Shultz owned, at Keyport, N. J. an interest in what would now be considered a very modest plant, operated with horses, and having a daily capacity of 40,000, or for the season, 8,000,000 brick. This passed to his son, Charles A. Shultz, who before long realised that the banks of the Hudson river not only afforded enormous advantages in the matter of shipping, but provided a better quality of the raw material, and in tempting abundance. Accordingly, in 1876, Charles A. Shultz removed to East Kingston and began, at first in a comparatively small way, a business which has been growing ever since, and which, under the management of his son, Henry H. Shultz, has reached a position of the highest Importance in the building material industry. The first notable step in the development of the Shultz yards on the Hudson river was when steam power was substituted for horses. This was in 1878, and from that time the business of the plant, increasing yearly with the recognised value of the "Shultz" brand, has climbed without one serious check, until, at the present writing it employs a plant the capacity of which is 138,000 per day, or 18,000,000 brick per season. These commercially satisfactory results have been in great part due to sheer persistence; but a particular "strong" quality of their clay banks and the incessant exercise of thought and care, with constant alertness to seize upon every chance of improvement, had quite as much to do with the reputation which the brand has earned of an almost perfect brick for general building purposes. The clay banks adjacent to the works yield also quantities of sharp sand This, with "culm" in the proper proportions, is used on the Shultz yards ' to form a brick in which there is both yellow clay and blue, one-third of the former and two-thirds of the latter. Special attention is given to the processes of mixing and tempering. The latter is carried on in a circular pit with a "tempering wheel" worked by steam power. So far there is no secret in the composition of the Shultz brick. But in the precedent process of mixing the case la somewhat otherwise; the strength, beauty and evenness of color for which this brick is noted has not been secured without years of thought and experiment, both by the late Mr. Shultz and the present manager of the estate. The expenditure of time, thought and capital upon all this repays it self in more than one way. There is the enormous saving involved in the fact that here the percentage of waste arising from the spoiled brick is lower than in almost any modern plant where brick are made on anything like the same large scale. The economy is continuous from the very first moulding to the finished product. It is based on -- apart from the careful and skillful mixing already referred to — a system of special attention in the details of "jarring" the moulds, of "dumping," "edging" and "hacking" upon the open yards which are in use here; then again it is a principle of the Shultz works that good drying is half the battle, if the manufacturer cares to produce an output of good color, and not the ugly grey which results from burning half-moist brick. Eternal vigilance is the price of success in these matters, and to complete the claim after watching the brick like delicate infants from "hack" to kiln, the "setting" is there done like a work of art, so as to ensure the perfection of draft for the burning. The fuel used in these kilns is hard coal, the kiln consuming, on an average 100 tons to each 1,000,000 brick. Another notable feature in the Shuliz works is their system of repairing all machinery and tools on the premises, a complete machine shop and staff of experts being maintained for that purpose. The well known corporation of The Terry Brothers Company Is represented in the market by two highly respected brands of brick: The "Terry" and the Terry Bros." The latter is made from blue clay alone; the former from mixed blue and yellow. The company's banks at Kingston and East Kingston, where, the two plants are situated, are of enormous extent. These deposits run mostly to blue clay, the East Kingston banks showing a large percentage of yellow, those at Kingston containing only blue. The banks are overlaid with an excellent quality of sand for both moulding and mixing. The company's plant includes eleven machines with an aggregate dally capacity of 250,000 or 30,000,000 bricks per season. Both circular pits and improved sod pits are used here -- eight „of the former and three of the latter. The product is shipped down the river on the company's own barges, of which it owns seven, varying in capacity from 200.000 to 325,000 brick per barge. The Terry Brothers Company enjoy the distinction of being the first concern on the Hudson river to burn brick with coal for fuel. This innovation was begun in 1884, and has been continued ever since. After more than twenty years experience with mineral fuel in their kilns, the management maintain that it gives a more uniform burn than can be obtained with wood fuel. In addition to this important point of uniformity, they believe that coal is more manageable, more amenable in nice adjustments and in every practical respect more satisfactory than wood. Besides the honor of being the pioneer coal burners of the Hudson river yards, the Terry Brothers Company claims a smaller percentage of broken brick than any other plant. This very favorable condition for a concern using only open-yard systems, which no doubt operates to the advantage of the consumer by reducing the waste for which the consumer has to pay in the long run — whether he knows It or not — is secured by a system of exceptionally careful handling, both of the green brick and of the burnt, in every one of the processes from moulding to culling. The dumping here is performed very gingerly, the edging is done as if the brick were so much porcelain, though with great speed, which can only be consistent with extreme care when as is the rule of this establishment, the workmen are all thoroughly practiced in their business. Lastly, the cullers lay down the selected brick taken from the kiln so deftly that very few foremen of buildings have ever had good cause to complain of ragged edges on the "Terry" or "Terry Bros." material since these brands appeared on the market. Artificial coloring material is not used in either brand, the natural color alone being relied upon to produce a good red brick. The Terry yards were founded in 1850 by the late David Terry. At his death, which took place in 1869, the business was taken up by his sons, Albert and Edwin, who carried it on in partnership until 1902, when Edwin Terry retired and the concern was incorporated as the Terry Brothers company: Jay Terry, vice-president; David Terry, secretary and treasurer. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

0 Comments

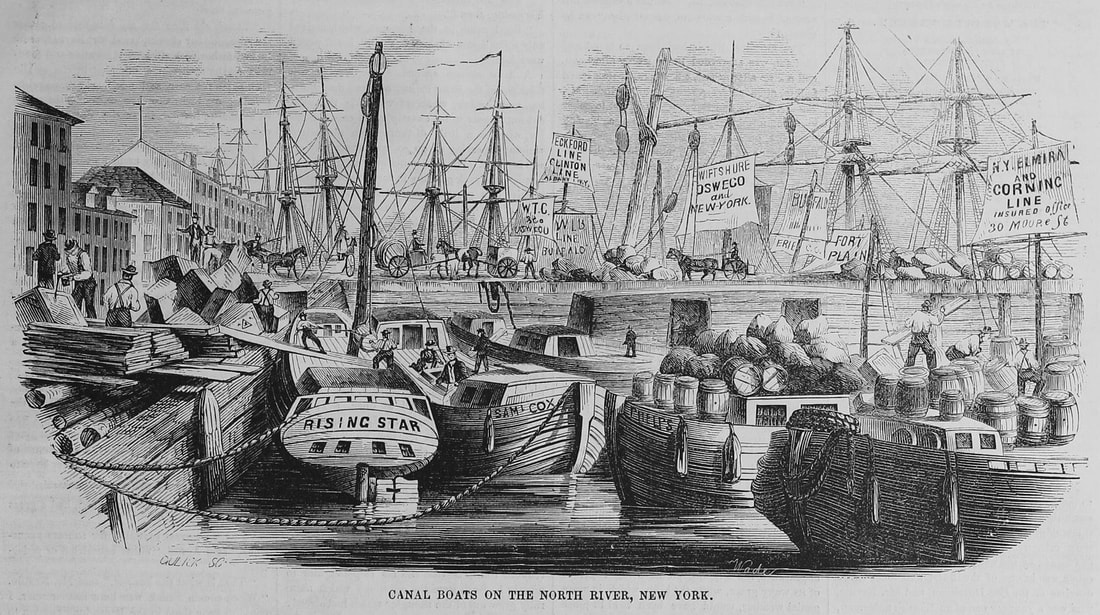

Editor's note: The following excerpts are from the January 3, 1875 issue of the "New York Times". Thank you to Contributing Scholar George A. Thompson for finding and cataloging this article. The language, spelling and grammar of the article reflects the time period when it was written. Loading Her Up. Scenes on the Docks. The Shipping Clerk – The Freight – The Canal-Boat Children. I am seeking information in regard to the late 'longshoremen's strike, and am directed to a certain stevedore. I walk down one of the longest piers on the East River. The wind comes tearing up the river, cold and piercing, and the laboring hands, especially the colored people, who have nothing to do for the nonce, get behind boxes of goods, to keep off the blast, and shiver there. It was damp and foggy a day or so ago, and careful skippers this afternoon have loosened all their light sails, and the canvas flaps and snaps aloft from many a mast-head. I find my stevedore engaged in loading a three-masted schooner, bound for Florida. He imparts to me very little information, and that scarcely of a novel character. "It's busted is the strike," he says. "It was a dreadful stupid business. Men are working now at thirty cents, and glad to get it. It ain't wrong to get all the money you kin for a job, but it's dumb to try putting on the screws at the wrong time. If they had struck in the Spring, when things was being shoved, when the wharves was chock full of sugar and molasses a coming in, and cotton a going out, then there might have been some sense in it. Now the men won't never have a chance of bettering themselves for years. It never was a full-hearted kind of thing at the best. The boys hadn't their souls in it. 'Longshoremen hadn't like factory hands have, any grudge agin their bosses, the stevedore, like bricklayers or masons have on their builders or contractors. Some of the wiser of the hands got to understand that standing off and refusing to load ships was a telling on the trade of the City, and a hurting of the shipping firms along South street. The men was disappointed in course, but they have got over it much more cheerfuller than I thought they would. I never could tell you, Sir, what number of 'longshoremen is natives or aint natives, but I should say nine in ten comes from the old country. I don't want it to happen again, for it cost me a matter of $75, which I aint going to pick up again for many a month." I have gone below in the schooner's hold to have my talk with the stevedore, and now I get on deck again. A young gentleman is acting as receiving clerk, and I watch his movements, and get interested in the cargo of the schooner, which is coming in quite rapidly. The young man, if not surly, is at least uncommunicative. Perhaps it is his nature to be reticent when the thermometer is very low down. I am sure if I was to stay all day on the dock, with that bitter wind blowing, I would snap off the head of anybody who asked me a question which was not pure business. I manager, however, to get along without him. Though the weather is bitter cold, and I am chilled to the marrow, and I notice the young clerk's fingers are so stiff he can hardly sign for his freight, I quaff in my imagination a full beaker of iced soda, for I see discharged before me from numerous drays carboys of vitriol, barrels of soda, casks of bottles, a complicated apparatus for generating carbonic-acid gas – in fact, the whole plant of a soda-water factory. I do not quite as fully appreciate the usefulness of the next load which is dumped on the wharf – eight cases clothes-pins, three boxes wash-boards, one box clothes-wringers. Five crates of stoneware are unloaded, various barrels of mess beef and of coal-oil, and kegs of nails, cases of matches, and barrels of onions. At last there is a real hubbub as some four vans, drawn by lusty horses, drive up laden with brass boiler tubes for some Government steamer under repairs in a Southern navy-yard. The 'longshoremen loading the schooner chaff the drivers of the vans as Uncle Sam's men, and banter them, telling them "to lay hold with a will." The United States employees seem very little desirous of "laying hold with a will," and are superbly haughty and defiantly pompous, and do just as little toward unloading the vans as they possibly can thus standing on their dignity, and assuming a lofty demeanor, the boxes full of heavy brass tubes will not move of their own accord. All of a sudden a dapper little official, fully assuming the dash and elan of the navy, by himself seizes hold of a box with a loading-hook; but having assert himself, and represented his arm of the service, having too scratched his hand slightly with a splinter on one of the boxes, he suddenly subsides and looks on quite composedly while the stevedore and 'longshoreman do all the work. Now I am interested in a wonderful-looking man, in a fur cap, who stalks majestically along the wharf. Certainly he owns, in his own right the half-dozen craft moored alongside of the slip. He has a solemn look, as he lifts one leg over the bulwark of a schooner just in from South America, and gets on board of her. He produces, from a capacious pockets, a canvas bag, with U.S. on it, and draws from it numerous padlocks and a bunch of keys. He is a Custom-house officer. He singles out a padlock, inserts it into a hasp on the end of an iron bar, which secures the after-hatch, snaps it to, gives a long breath which steams in the frosty air, and then proceeds, with solemn mein, to perform the same operation on the forward hatch. Unfortunately, the Government padlock will not fit, and, being a corpulent man, he gets very red in the face as he fumbles and bothers over it. Evidently he does not know what to do. He seems very woebegone and wretched about it, as the cold metal of the iron fastening makes it uncomfortable to handle. Evidently there is some block in the routine, on account of that padlock, furnished by the United States, not adapting itself to the iron fastenings of all hatches. He goes away at last, with a wearied and disconsolate look, evidently agitating in his mind the feasibility of addressing a paper to the Collector of the Port, who is to recommend to Congress the urgency of passing measures enforcing, under due pains and penalties, certain regulations prescribing the exact size of hatch-fastenings on vessels sailing under the United States flag.  "Canal Boats on the North River, New York" by Wade, "Gleason's Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion," December 25, 1852. Note the sail-like signs for various towing lines and destinations, as well as the jumble of lumber and cargo boxes on the pier at left, waiting to be loaded onto the canal boats (or vice versa). I return to my schooner. By this time the wharf is littered with bales of hay, all going to Florida. I wonder whether it is true, as has been asserted, that the hay crop is worth more to the United States than cotton? I think, though, if cotton is king, hay is queen. Now comes an immense case, readily recognized as a piano. I do not sympathize with this instrument. Its destination is somewhere on the St. John's River. Now, evidently the hard mechanical notes of a Steinway or a Chickering must be out of place if resounding through orange groves. A better appreciation of music fitting the locality would have made shipments of mandolins, rechecks, and guitars. Freight drops off now, and comes scattering in with boxes of catsup, canned fruits, and starch. Right on the other side of the dock there is a canal-boat. She has probably brought in her last cargo. And will go over to Brooklyn, where she will stay until navigation opens in the Spring. There is a little curl of smoke coming from the cabin, and presently I see two tiny children – a boy and a girl – look through the minute window of the boat, and they nod their heads and clap their hands in the direction of the shipping clerk. The boy looks lusty and full of health, but the little girl is evidently ailing, for she has her little head bound up in a handkerchief, and she holds her face on one side, as if in pain. The little girl has a pair of scissors, and she cuts in paper a continuous row of gentlemen and ladies, all joining hands in the happiest way, and she sticks them up in the window. This ornamentation, though not lavish, extends quite across the two windows, the cabin is so small. Having a decided fancy, a latent talent, for making cut-paper figures myself, I am quite interested, as is the receiving clerk. I twist up, as well as my very cold fingers will allow, a rooster and a cock-boat out of a piece of paper, and I place them on a post, ballasting my productions with little stones, so that they should not blow away. The children are instantly attracted, and the little boy, a mere baby, stretches out his hands. My attention is called to a dray full of boxes, which are deposited on the wharf for our schooner. Somehow or other the receiving clerk, without my asking him, tells me of his own accord what they contain – camp-stools. I can understand the use of camp-stools in Florida: how the feeble steps of the invalid must be watched, and how, with the first inhalation of the sweet balmy air, bringing life once more to those dear to us, some loving hand must be nigh, to offer promptly rest after fatigue. I return to my post, but alas my rooster and cock-boat have been blown overboard; the wind was too much for them. I kiss my hand to the little girl, who smiles with only one-half of her face; the stiff neck on the other side prevents it. The little boy points to the post and makes signs for more cock-boats. Snow there happens to come along on that wharf an ambulant dealer with a basket containing an immense variety of the most useless articles. He has some of the commonest toys imaginable, selected probably for the meagre purses of those who raise up children on shipboard. There are wooden soldiers, with very round heads but generally irate expressions, and small horses, blood-red, with tow tails and wooden flower-post, with a tuft of blue moss, from which one extraordinary rose blossoms, without a leaf or a thorn on the stem. On that post for ten cents that ambulant toy man put five distinct object of happiness, when the shipping clerk interfered. "It's a swindle, Jacob," he said. That young man was certainly posted in the toy market along the wharves. "You ain't going to sell those things two cents a piece, when they are only a penny? You must be wanting to retire after first of the year. Bring out five more of them things. Three more flower-pots and two more horses. The little girl takes the odd one. What's this doll worth? Ten cents! Give you five. Hand it over. Now clear out. I see you, Sir, watching them children. Poor little mites. No mother, Sir. Father decent kind of fellow; says their ma died this Spring. Has to bring 'em up himself, and is forced to leave them most all day. He is only a deck-hand and will be the boat-keeper during Winter. Been noticing them babies ever since I have been loading the schooner – most a week – and been a wanting to do something for their New-Year's. A case of mixed candies busted yesterday, and they got some. They have been at the window ever since, expecting more; but nothing busted. You can't get in; the cabin is locked, but I can manage it through the window." So my young friend climbed on board, with the toys in his pocket, lifted up the sash, and passed through the toys one by one, the especial rights of proprietorship having been carefully enjoined. Presently all the soldiers and the follower-pots were stuck in the window, and the little girl was hugging the doll. "Loading her up; taking in freight for a vessel of a Winter's day on a wharf isn't fun," said the young gentlemen sententiously. "I shouldn't think it was," I replied. "In fact, there ain't much of anything to see or do on a wharf which is interesting to a stranger." "You are from the country, ain't you?" asked the young man with a smile. "Never seen New-York before? Wish you a happy New Year, anyhow." I did not exactly how there could be any reservation as to wishing me a happy New Year whether I was from the country or not, but supposing that this singularity of expression arose from the general character of the young man, or because he was uncomfortable from the frosty weather, I returned the compliment, inquiring "whether a stiff neck was not very hard on children," and not being a family man, added, "They all get it sometimes, and get over it, don't they ?" "It ain't a stiff neck, it's mumps. Mother sent me a bottle of stuff for the child three days ago, and her father has been rubbing it on, and she's most over it now. When I was a little boy," added the clerk reflectively, "toys cured most everything as was the matter with me." "Just my case," I replied, as we shook hands and I left the wharf. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Happy Labor Day! For today's Media Monday, we thought we'd highlight this recent lecture by Bill Merchant, historian and curator for the D&H Canal Historical Society in High Falls, NY. "Child Labor on the D&H Canal" highlights the role of children on one of the biggest economic drivers of the Hudson Valley in the 19th century. Child labor was a huge issue in 19th and early 20th century America (learn more) throughout nearly every industry, including the maritime and canal industries. Although many canal barges were operated by families, many were also operated by single men who exploited orphans and poor children, often with fatal results. Children were most generally used as "drivers," also known as hoggees, who walked with or rode the mule or horse who pulled the barge through the canal. Work was long, often sunup to sundown or even longer, as the faster barges could get through the canal, the faster they could return and pick up a new cargo, thus making more money. The Kingston Daily Freeman reported a Coroner's Inquests on July 18, 1846, which recorded several deaths related to Rondout Creek and the D&H Canal, including a young boy. It is transcribed in full below: Coroner's Inquests. On the 11th, Coroner Suydam [sp?] held an inquest at Rondout on the body of Joseph Marival, a colored hand on board the sloop Hudson of Norwich, Ct. He went in the creek to bathe, and was accidentally drowned. The same officer held an inquest at [?] Creek Locks on the body of Henry Eighmey, on the 15ht, drowned in the canal by a fall from a boat about noon. We have record of a third by Mr. Suydam, held at Rosendale on the 12th, on the body of Andrew J. Garney, a lad of ten years old, a rider, who it was supposed fell from his horse into the canal about day break of that morning, a verdict conformable being rendered. In connection with the last case, we would remark, that the crew consisted of one man with the driver who was drowned. That the boat had been running all night [emphasis original]; that about three o'clock in the morning the man spoke to the land and was answered, and that some time afterwards he missed him, and concluded he must have fallen into the canal. Is there any thing strange in the fact that a lad of ten years, worn down with the fatigues of a long day and a whole night in the bargain, should drop into another world? Now we do not mean to mark this as a singular case, by any means. It is but one of the like occurring almost daily on the canal. Lads are hired at a mere pittance, and men are determined to get as much work out of them as possible, without the least regard to health, comfort, or safety. The poor children are toiling from daylight to dark, and if in addition they are forced to nod all or part of the night, the consequent sleep and death is nothing to be wondered at. We would call attention to this subject on the part of those who may able to devise a mode of reaching such cases. Nor would it be out of place in the Coroner's jury in the next instance should state the whole [emphasis original] truth in the verdict. Most laborers on the canal were paid at the end of the season, but it was not uncommon for unscrupulous barge operators to cheat the boys of their wages and abandon them in random canal towns. Even when working with their families, children who lived aboard barges sometimes had hard lives. Although the Delaware & Hudson Canal closed in 1898, children and families continued to work on the newly revamped New York State Barge Canal system and canals in Ohio and elsewhere into the mid-20th century. In 1923, Monthly Labor Review published an article entitled "Canal-boat Children," which looked at the labor, education, and living conditions of children on canal boats. Of particular interest was safety, as the threat of drowning or being crushed in locks was near-constant. Still, many families were able to make decent livings aboard canal barges, until tugboats took over canal barge towing in the mid-20th century. To learn more about New York Canals, visit the Hudson River Maritime Museum's exhibit "The Hudson and Its Canals: Building the Empire State," or visit the newly revamped D&H Canal Museum in nearby High Falls, NY. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

In February of 1946, tugboat crews in New York Harbor had had it. They had been trying since October, 1945 to negotiate an end to the wartime freeze on wages, to reduce hours from 48 per week to 40, to receive two weeks paid vacation per year, and perhaps most importantly, to end the practice of stranding workers in far-away ports and forcing them to pay their own way home, without success. Although the war was over, the federal government was still regulating the price of freight, which meant that shipping companies didn't want to raise wages. Frustrated, the tugboat workers struck. Starting February 4, 1946, tugboats did not move coal or fuel in the nation's busiest port. Manhattan is an island, and maritime freight played a huge role in supplying the city with fuel, food, and other supplies, as well as removing garbage by water. At the time of the strike, officials estimated the city has just a few days of reserve coal. The strike was covered in several newsreels at the time. British Pathe put together this short report on the strike: Universal put together this newsreel, sadly presented here without any sound: Newly-elected mayor William O'Dwyer did not react well to the strike. Facing a fuel shortage for one of the nation's most populous cities in midwinter was no laughing matter, but O'Dwyer implemented measures that many later deemed an overreaction to the strike. He essentially rationed fuel for the entire city, prioritizing housing for the sick and aged, but enforcing a 60 degree maximum temperature for all other building interiors, turning off heat in the subway and limiting service, shutting down all public schools on February 8, and by February 11 shutting down entirely restaurants, stores, Broadway theaters, and other recreational venues. The bright lights of Times Square and elsewhere were also turned off to conserve electricity, as illustrated in this second newsreel from British Pathe: After 18 hours of shutdown, the shipping companies and the tugboat unions agreed to end the strike and enter into third party arbitration for their contract. Tugboats started moving fuel again, and the lights turned back on. And that's the end of the story - or is it? On February 14, 1946, the New York Times published an article entitled "Lessons of the Tug Strike," whereby they largely blamed O'Dwyer for the costly shutdown. "New York tugboat workers and management have sent their dispute to arbitration after a ten-day strike that endangered life and property, cost business millions of dollars and paralyzed the whole city for a day. We may well breathe a sigh of relief and at the same time examine some aspects of this incident that offer guidance for the future," the Times wrote, and went on to ask that O'Dwyer never do that again "unless the need is clearly established." As for the tugboat workers, it would take nearly another year for the threat of a strike to fade completely. Negotiations continued throughout 1946, with little movement, until the threat of another strike emerged in December of 1946. It was avoided by additional arbitration with Mayor O'Dwyer's emergency labor board. Finally, the arbitrators won concessions from both sides, and on January 5, 1947, the New York Times reported that a settlement had been reached. The tugboat workers got their 40 hour workweek, but not the same wages as 48 hours of work. They did get an 11 cent per hour wage increase along with a minimum wage for deck hands, a five day workweek, and time and a half for Saturdays and Sundays. However, the contract was only for 12 months, and in December of 1947, another strike was on the table as workers struggled for another wage increase. The strike was averted with more concessions from the companies, including a ten cent raise, food allowances, and more. But in the fall of 1948, the contract was up again, and the specter of the February, 1946 shutdown arose as a strike was once again on the table as part of the negotiations. Strikes were common in the years following the Second World War, in nearly every aspect of American society. In particular, the Strike Wave of 1945-46 impacted as many as five million American workers across all sectors. The strikes, although sometimes effective in improving worker wages and conditions, were largely unpopular with the general public. In 1947, Congress overrode President Truman's veto of the Taft-Hartley Act, which limited the power of labor unions and ushered in an era of "right to work" laws. Learn more about the strike wave in this podcast from the National WWII Museum. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

This year is the 100th anniversary of the opening of the Rondout Suspension Bridge (or the Wurts Street Bridge, the Port Ewen Bridge, or the Rondout-Port Ewen Bridge, etc!), which opened to vehicle traffic on November 29, 1921. The bridge was constructed to replace the Rondout-Port Ewen ferry Riverside, which was affectionately (or not so affectionately) known as "Skillypot," from the Dutch "skillput," meaning "tortise." Spanning such a short distance, the ferry was small, and with the advent of automobiles, only able to carry one vehicle across Rondout Creek at a time, causing long delays. Motorists advocated for the construction of a bridge, which was set to begin in 1917. But when the United States joined the First World War that spring, construction was delayed until 1921. Staff at the museum had long known that there was a woman welder on the construction crew, but we knew nothing beyond that. Had she learned to weld at a shipbuilding yard during the First World War? Was she a local resident, or someone from far away? There were more questions than answers, until a few weeks ago when HRMM volunteer researcher and contributing scholar George Thompson ran across a newspaper article that he said went "viral" in 1921. Entitled, "Woman Spider," and featured in the Morning Oregonian from Portland, Oregon, the article indicated that "Catherine Nelson, of Jersey City" was our famous woman welder. Having a name sparked off a flurry of research and the collection of 37 separate newspaper articles, all variations on the same theme. Fourteen articles were all published on the same day, September 3, 1921. But only one had more information than the rest - "Never Dizzy, Says Woman Fly, Though Welding 300 Feet in Air. Mrs. Catherine Nelson Has No Nerves, She Loves Her work and Is Paid $30 a Day," published in the Boston Globe. Which, wonderfully, included a photo of Mrs. Catherine Nelson! Here is the full article from the Boston Globe: KINGSTON, NY, Sept 3 – Three hundred feet above the surface of Rondout Creek, a worker in overalls and cap has been moving about surefootedly for several days on the preliminary structure that is to support a suspension bridge across that stream. Thousands of glances, awed and admiring, have been cast upward at the worker, stepping backward and forward and wielding an instrument that blazed blue and gold flames and welded together the cables from which the bridge will swing. “Some nerve that fellow’s got!” was a favorite remark, to which would come the reply: “You said it!” But there’s more than awe and admiration now directed aloft, for it turns out that “that fellow” is a woman – Mrs. Catherine Nelson of Jersey City, the only woman outdoor welder in the world. Isn’t Afraid of Work She isn’t afraid of her work; she loves it; and – of course this is a big inducement – she gets $30 a day for it. She has never had an accident in her seven years’ experience at the trade. She’s as strong as a man, weighing 180 pounds to her 5 ft 6 in of height, and is a good looking, altogether feminine, Scandinavian blonde. She’s 31. "I was born in Denmark and was married there," Mrs Nelson told the reporter. "But my husband died and left me with two small children, so I had to shift for myself. "For two years I worked as a stewardess on an ocean liner, but I could not have my children with me and my pay wasn’t much, so I cast about for harder and better-paid work, so I could have my own little home. "My husband was a garage keeper in Denmark, and I had worked with him, so I knew something of machinery. I got a job in a machine shop in this country. They had an electrical welding department there and I soon got a place there. I grew to love the work and I’ve been at it for seven years. Does Not Get Dizzy "This is the highest job I’ve been on, but one of my first was on a water tower at Bayonne, 225 feet tall. I’ve been on smokestacks and tanks plenty. No, I don’t get dizzy. I wear overalls and softsoled shoes, and I’m always sure of myself, for I haven’t any nerves. "I like to pride myself on the fact that I’ve never turned down a single welding job because it might be dangerous.' Showing Mrs. Nelson’s standing in her trade, it was she who was sent up from Jersey City when Terry & Tench, the bridge contractors, asked the Weehawken Welding Company for their best operator. "My children and I are happy and comfortable now,' she said; 'and I hope to afford to take them home to Denmark for Christmas. But I will come back and tackle some more welding jobs." The last published article we could find, "Says She Has No Nerves," published in the Chickasha Star, in Chickasha, Oklahoma on September 16, 1921, is almost a verbatim reprint of the Boston Globe article. As a cable welder, Catherine Nelson was responsible for welding together the cable splices that made up the longest length of the cable span. Wire cable is produced in limited sections, and often the cable was spliced together with welding, which is among the strongest of the splices, replacing the earlier versions of wire wrapping, and later screw splicing. Welded splices are stronger and more durable than both. Most welding was typically done in a shop setting, but some, as with Catherine Nelson, were done on site. She may have done additional welding while walking the cables, as most of the newspaper stories focus on her working 300 feet up in the air. Once the initial suspension cables were in place, supporting cables for the deck of the bridge could be constructed, which were designed to provide additional support, rigidity, and to spread the weight load across the entire bridge. This particular bridge is said to be unique for its "stiffening truss," located under the deck of the bridge. The bridge was opened on November 29, 1921 to great fanfare. It remains the oldest suspension bridge in the Hudson Valley, predating the longer Bear Mountain Bridge by several years. As for Catherine Nelson? We've yet to find any additional information about her, but if you have any leads, or are a relative with family stories, please let us know in the comments! AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson is the Director of Exhibits & Outreach at the Hudson River Maritime Museum, where she has worked since 2012. She has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Today's Featured Artifact is this beautiful brass engine room gong, once found on a steamboat owned by the Homer Ramsdell Transportation Company, based in Newburgh.

Most steamboats and many diesel tugs were known as "bell boats," meaning the captain or pilot and the engineers communicated by a system of bells. Up in the wheelhouse, the pilot could only control the direction of the boat, with the pilot's wheel. If he wanted to change direction or speed, he had to communicate with the engineers down in the engine room. Imagine driving a car where one person is steering, and another person, who cannot see the road, is controlling the gas pedal and brakes. Thankfully, most boats are not as fast or maneuverable as a car, but the changes still had to be quickly executed to ensure safe and smooth operation of the boat. The larger, louder bell, called a "gong," signaled a change in direction. Smaller bells, called "jingles," usually signaled a change in speed. Controls in the pilot house were connected to the bells in the engine room, making them ring. Many transportation companies had their own code, although New York Harbor had a code shared by many boats. In this sound clip, collected by steamboat sound recording enthusiast Conrad Milster, we can hear the gong and jingle aboard the Newburgh ferryboat Dutchess.

Here are some examples of simplified bell signals, to give you an idea of how the system would work.

When the steamboat was stopped:

When working ahead or backing (moving forwards or backwards):

Jingles to change speed:

Signals could also be combined. For example, when stopped:

Mystic Seaport operates a historic steamboat that still uses the bell and jingle system. In this video, the captain of the Sabino explains how he and the engineer communicate. The video includes great footage from the engine room as well.

You can visit the museum's engine room gong, which is on permanent display in the East Gallery, along with many other fascinating maritime artifacts, at the Hudson River Maritime Museum. We hope to see you soon!

If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Harris Nelson woke up on a normal day in January, 1906 not knowing he, his son, and fifteen others would be swallowed by the earth just after lunch. Harris was a merchant in the small but prosperous town of Haverstraw, located approximately 60 miles south of the Hudson River Maritime Museum in New York’s Rockland County. The day Harris Nelson died the town boasted around 6,000 residents, with a population nearly double that today. Inventively called “Bricktown” more often than not, Haverstraw in 1906 was still benefiting from the Hudson River brick industry boom following the great New York City fires of 1835 and 1845, which left hundreds of wooden structures destroyed and a huge demand for brick as a less flammable building material. The Hudson River Valley, with its abundance of clay deposits left behind in the wake of post-glacial lakes nearly 12,000 years ago, stood up to answer the demand. Including the one in Haverstraw, over 40 brick factories cropped up along the Hudson, and where there were factories, there were often mines. During most of the 19th century, clay was extracted from beneath Haverstraw until its residents lived and worked on hollow ground. The eventual and somewhat inevitable partial collapse of the mine began without fanfare, a slow cracking of the ground that some Haverstraw residents paid no mind. When it was evident homes and lives were in danger, it was too late for Harris and Benjamin Nelson, both of whom were either crushed in the collapse or killed by the ensuing fire, sparked by the toppled stoves of destroyed homes. The initial disaster took twelve lives, the additional five lost by men and women rushing to the aid of their neighbors. Adding fuel to the literal fire was the frigid weather, which discouraged residents from leaving their homes, as well as a water main break that prevented fire-fighters from dousing the flames. It seemed that residents were attacked on several fronts by forces that merged to make the clay pit disaster an incredibly deadly one. And yet, Haverstraw’s residents carried on in its wake, and managed to rebound from the landslide of 1906 to continue as a place worthy of the name “Bricktown.” Remembering this dark spot in Hudson River history is not merely a cautionary tale in resource depletion; Haverstraw’s ability to carry on and grow into the diverse and history-rich village it is today also serves as a needed reminder that there’s a tomorrow after even the worst of times. AuthorAudrey Trossen is a Hudson Valley native and worked as an intern with the Hudson River Maritime Museum during the summer of 2017. She is a current undergraduate student at Smith College in Northampton, MA where she majors in Geology and concentrates in Museum Studies. |

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 [email protected] Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |