History Blog

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Media Monday post continues coverage of the bitter cold winter of 1934. This short film from British Pathe/Reuters features aerial photographs of snow bound Manhattan after the blizzard. Roads and automobiles were snow bound and ports were frozen over due to the Blizzard of 1934. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

0 Comments

Editor's Note: The following is a verbatim transcription of a chapter from Spalding's Winter Sports by James A. Cruikshank, published in 1917 and part of the Ray Ruge Collection at the Hudson River Maritime Museum. Many thanks to volunteer Adam Kaplan for transcribing this booklet. After a trial of all the sports of all the year, from running foamy rapids in your own canoe to sailing over the earth on the wings of an airplane, the honest critic will award the palm to Ice Boating for its unrivaled excitement, its unapproached speed and its glorious intoxication. No man ever believed that he had been nipped by the frost while he was making his first trip in an ice yacht; his fast beating heart was pumping too much red blood through his delighted body to permit any such thing! Ninety miles an hour is credibly reported as the occasional speed of the ice yacht. The greatest authority on the subject is of the opinion that no real limit can be set for the speed of the craft, since ideal conditions of wind and weather and ice, and ideal construction of the craft for utilizing these conditions have never been combined and probably never will be. It is known beyond the shadow of a doubt, however, that the ice yacht can and does sail faster than the wind which is blowing at the time, strange as this statement may appear to the uninformed. For the absolute beauty of motion, with least sensation of striving after speed, with smallest appreciable evidence of friction, and almost utter absence of that noise which is the general accompaniment of all fast traveling, the ice yacht is absolutely unique and unsurpassed. An initiation trip of a few miles will furnish sensations so novel and so fascinating as to be incomparable with any other sport the winter lover has tested; he will be a hardened and blasé soul if then and there he does not vow further acquaintance with the thrilling pastime. The ice yacht is a development of the ice boat, which was a square box set on steel runners and propelled by a sail. It may be said that for purposes of easy definition the only differences now existing between an ice boat and an ice yacht are differences of cost; like the “pole” of the country boy angler and the “rod” of the city angler, both the ice boat and the ice yacht have the same uses and furnish the same sport. If the craft is simple and perhaps home-made it will probably be an ice boat; if it is made by professionals, with due reference to the “center of effort” in the placing of sails, has red velvet cushions and that sort of thing, you are privileged to call it an ice yacht. Either one will give all the sport any reasonable man is entitled to in this wicked world. Ice yachts cost between $500 and $5,000, although there is said to be at least one which cost over this latter figure. Ice boats cost from $5 up, depending largely upon who does the work of making them. Along the lower reaches of the Hudson River there are any number of successful ice boats which cost less than $25 apiece, and they furnish magnificent sport. Any small boy with a knack for mechanical work can make himself an ice boat that will serve every purpose and teach him the rudiments of steering and managing the craft; and he will find many surprises in learning the new sport, even though he may be a clever small boat sailor on water. The handsomest and finest ice yachts in the world are found along the Hudson River in New York State, near the city of Poughkeepsie. There are also many fine ice yachts used on the Shrewsbury River in New Jersey, on Orange Lake, Newburgh, N.Y., on Lakes George and Champlain, and a very considerable interest in the sport among the winter-loving sportsmen of the northwestern United States, especially Wisconsin, Michigan and Minnesota. With that daring characteristic of the western folks, the ice yachts of the Northwest seem to be planned more with reference to general use under all conditions of smooth, rough or snowy ice than some of the more highly perfected eastern craft which are seldom used unless conditions are perfect. Thus the westerner gets a much larger amount of sport out of the season than the easterner; fourteen days of good sport is all that some of the eastern yacht enthusiasts expect during a full season. While there are several interesting designs of ice yachts in general use among the experts of the sport, and any number of “freak” designs, some of which have demonstrated their ability to walk away with handsome prizes, there has come to be comparative uniformity as to the general lines of construction. And from these lines it would be best for the ice yacht builder not to deviate too much, although minor constructive details still leave considerable room for experiment and originality. The generally accepted design of the fastest and best ice yachts is that of a cross, in which the center timber, also sometimes called the backbone or the hull, running fore and aft, is crossed, just a little forward of half its length, by the runner plank. A successful western design consists of two center timbers spread apart several feet in the center of the craft and joined at the forward end, or bowsprit, and at the extreme stern, where the rudder is located, The best material for the backbone or center timber is either basswood or butternut. Oak is generally used for the runner plank; clear spruce for the mast and spars. The cockpit or seat is merely a place for the steersman and guests to half lie or half sit, and is generally provided with a combing and rails. Cushions of hair, cork, moss, or hay are provided. All running gear, except the main sheet rope, is of plow steel rope or flexible wire. Sails are of cross-cut pattern used in racing water yachts. The most important items of the ice yacht, after the frame, are the runners and the rudder. Here great care should be exercised to get the right thing. Certain fixed standards of material, design and hang are almost universal. The runners and the rudder, which are almost identical in shape, are of V-shaped castings; the very best grade of cast iron seems to be the most preferred. The fact that, after a few weeks of sailing, these runners have to be sharpened, and that the friction and heat developed in their use gives them a dense hardening which it takes considerable filing to penetrate, warrants the use of runner material not too hard at the start. Tool steel, Norway iron, phosphor bronze and even brass have been used; the best results seem to come from good quality castings. There is difference of opinion whether there should be rock to the runner or considerable flat area, but the consensus of opinion favors a slight rock to the runners and less to the rudder. Between the rudder and the bottom of the cockpit a large rubber block is inserted to take some of the jar and vibration. The runners are permanently fastened to the runner plank, allowing play up and down, while the rudder is set in a rudder post which has a Y at the lower end, allowing the rudder vertical motion. The tiller should be a long iron bar wrapped with cord, lest some thoughtless guest, with perspired hand, comes to grief. Cockpit rails should be similarly wrapped. The craft to which reference has so far been made is of the general Hudson River pattern. No dimensions have been given, but for the further information of the interested reader planning to enter the sport, the following dimensions of a successful ice yacht of this type are here appended. The figures will be useful to those planning smaller craft if the same proportions are observed, although the size, known as the Two Hundred and Fifty Square Foot Area Design, has proven itself especially useful as an all-around fast ice yacht for the largest number of days. Backbone, 30 feet over all, 4 1/2 inches thick, 11 inches wide at runner plank; nose, 3 1/2 inches; heel, 4 3/4 inches; runner plank over all, 16 feet 8 inches; cut of runners, 16 feet; length of cockpit, 7 feet 6 inches; width, 3 feet 7 inches. Mast stepped 9 feet 6 inches aft of backbone tip. The rig is jib and mainsail; dimensions of jib, on stay, 12 feet; leech, 9 feet 9 inches; foot, 7 feet 3 inches; mainsail, hoist, 12 feet; gaff, 10 feet 3 inches; leech, 24 feet; boom, 18 feet. Sail area, 248.60. Such a craft as this can be built for about $200. The ice yacht sailor will learn many things about sailing which he never learned from handling water craft. The sails are trimmed flat all the time in ice yacht sailing. There is no such thing as “going before the wind” with free sheet, in the manner familiar to water yachtsmen, for the excellent reason that no ice yacht will hold its direction sailing in this fashion, in wind of any considerable speed. The marvelous ease with which the craft is steered will amaze every yachtsman, especially those familiar with the hard helm of the average catboat. Many a beginner at the Ice Yachting game turns his tiller too sharply and finds himself flung off and sailing away over the smooth ice while his craft spins on her center. The ordinary way to stop the craft is to run up into the wind; sometimes the rudder is turned square across the direction after this position is attained, and a quick stop can thus be made, but it is a severe strain on the craft. Ice yachts are “anchored” by heading them into the wind, loosening the jib sheets and turning the rudder crosswise. Frequently passengers or crew are carried on the extreme cuter edges of the runner plank, and the sensation when this runner gradually rises in the air is thrilling indeed. It is not generally regarded as good sailing, however, to have the runners leave the ice much. It is much better and much safer for the amateur at the sport to learn something of the handling of the craft from experienced friends before he ventures abroad alone; there are immense boulders away up on the dry land of the Hudson’s shores which have been the lodging places of some fine new ice yachts that the tyro sailors could not even steer, much less stop. The most interesting novelty in ice-yachting seen in recent years is the invention of Mr. William H. Stanbrough of Newburgh, N.Y., and consists of a cockpit which can be made to swing from side to side of the yacht, according to the point of sailing, etc. The cockpit rests on the runner plank and on a track, and is provided with wheels which permit it to run easily back and forth. The center of the cockpit is well forward, providing better distribution of weight and, by means of drums and cables, the steering is managed from a tiller post, much as the steering of the sailing canoe is done. The shifting of weight makes it possible to either keep the craft on three runners or to lift the windward runner in the air at will. The device has been tested for several seasons and is enthusiastically praised by those who have adopted it. The greatest authority on ice yachting in America is the noted sportsman, Mr. Archibald Rogers, of Hyde Park, N.Y., whose interest in the sport is not confined to the handling of his famous ice yachts, among which the “Jack Frost” ranks first, but includes as well scientific researches as to materials for construction of the ice yacht, and whose amateur workshop and ice yacht house is a storehouse of information on the sport. The most successful builder of ice yachts is George Buckhout, Poughkeepsie, N.Y., builder of the famous successes, “Jack Frost,” owned by Mr. Archibald Rogers, and “Icicle,” Mr. John Roosevelt, owner, and many Western ice yachts. THE GREAT SOUTH BAY “SCOOTER” Valuable as is the ice yacht as a gift of America to the sport of the world, it is probable that the craft known as the “Scooter,” which originated on the waters of the Great South Bay, Long Island, N.Y., excels it in value, for already this unique inventions been taken up not merely by the sportsmen of the world but by hundreds of others whose requirements for sport and work the odd craft seems exactly to fill. Many lives have already been saved by the “scooter,” and its growing popularity wherever open water, which wholly or partly freezes, is found, indicates that it has an important future. The “scooter” may be properly classed among ice yachts, since it truly sails successfully over ice. But it does much more than this, for it will also sail in water, safely go from ice to open water and back again from open water to ice. There is no craft or machine, so far devised by man, so nearly similar to the amphibious wild duck, and the simplicity of the construction of the craft, as well as its ease handling, renders it more than ordinarily interesting and valuable to seekers after novelties in sport that are worth while. The “scooter” is an evolution. It is a cross between the round-nosed spoon bottomed ducking boat rigged with sails and the old pioneer ice boat which was nothing more than a square box on iron runners. Some of the best “scooters” now in use on the Great South Bay were built by men who never did a stroke of boat building before. Some were built by boys. Anybody can build one, and the completed craft, sails and all, ought not to cost over $100. They are the safest, the most compact, the easiest stowed, the most durable, and the greatest sports furnishing toys for their cost and size which the winter loving folks of the world have so far been introduced to. Let’s get acquainted with them. Imagine the bowls of two wooden spoons 15 feet long, with a width, or beam, of 4 to 5 feet. The upper wooden shell, which is the deck of the craft, is curved over from bow to stern and from one side to the other like the back of a turtle. The lower wooden shell is almost a duplicate of the upper one, which makes the craft almost flat bottomed. There is no keel or centerboard or opening of any kind on the bottom. There is a cockpit about 5 feet long and about 2 feet wide, around which runs a heavy combing 3 inches high and very solidly built. The runners of the craft are 20 inches apart, along 10 feet of the bottom, are slightly rocked, 1 inch wide and 1 1/2 inch high. They are of steel or brass, the latter allowing of quick sharpening for races or hard ice. The mast, set well aft, is about 10 feet in height, and the handiest rig is jib and mainsail, the latter either with boom and gaff or sprit. A small boom for the foot of the jib is customary, and in the handling of this jib is the whole secret of steering and managing the craft. The bowsprit should be large and project about 3 feet beyond the hull. In many “scooters” the bowsprit is made removable so that larger ones may be substituted for changes in weather. The spread of sail in a “scooter” is lateral rather than high, and must be well astern since the canvas of the craft is all that is used to steer her, no rudder of any kind being used. A “scooter” of 10 foot mast will carry a mainsail having an 8 foot gaff and a 15 foot boom, with a leech of about 15 feet. The foot of the jib will be 7 feet and the leech the same, or slightly more. The material used for the making of the “scooter” is generally pine and oak. Additional items of the equipment consist of a pike pole having sharpened ends and a pair of oars. Steering is done by a combination use of the jib, change in the location of the skipper or crew, and occasionally by the manipulation of the mainsail. By paying out the jib sheet and hauling in on the mainsheet, the “scooter” will come up into the wind like a fin keel water yacht; she will do this even more prettily if the weight of the skipper or crew is moved slightly forward, throwing weight on the forward part of the runners. Like an ice yacht, the “scooter” does not sail well before the wind; one must tack before the wind as well as into it. Two is the customary crew, although three are sometimes carried. Open water must be dived into exactly straight or an upset will occur. Manipulation of the mainsail and jib is most important at this critical point of sailing. To climb up from the open water onto ice again is easier for the “scooter” than one would believe who has not seen it. The weight of the crew is shifted aft, there is a bit of helping with the sharp crook of the pike pole and off she goes over the smooth ice again. The headquarters of the “scooter” interest is found in the vicinity of Patchogue, Long Island, N.Y., and the picturesque events run off there every winter draw thousands of New Yorkers. The most noted designer and builder of “scooters” is Henry V. Watkins of Bellport, N.Y., on the Great South Bay, and the patron saint of the quaint new sport is the noted sportsman, raconteur and host, Captain Bill Graham, of The Anchorage, Blue Point, Long Island. The seeker after something novel in winter entertainment is strongly urged to make the acquaintance of the new sport of “Scootering” as practiced here in Great South Bay, where the sport was born. AuthorJames A. Cruikshank was an expert on outdoors sports during the first half of the 20th century. Born in Scotland but spending most of his life in New York, he was the editor of The American Angler magazine, Field and Stream, and wrote numerous articles for a wide variety of other magazines and newspapers throughout his career, including the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. He also published at least three books: Spalding’s Winter Sports (1913, 1917), Canoeing and Camping (1915), and Figure Skating for Women (1921, 1922). He also contributed a chapter on artificial lures to The Basses: Freshwater and Marine (1905). In addition to his writing, Cruikshank was involved in public speaking, doing talks on outdoor sports sometimes illustrated by motion pictures. An avid photographer, Cruikshank’s photos often featured in his illustrated lectures, his articles, and his books, as he encouraged readers to take their own cameras out-of-doors. He had a home in the Catskills as well as a home and offices in New York City, and in the 1930s he helped found the Hudson River Yachting Association. At one point, he managed the Rockefeller Center ice skating rink, and another in Rye, NY. His wife Alice was also an avid camper and hiker, and they often traveled together. In 1909, Alice went “viral” in newspapers around the country by being the first person to blaze a trail between Mount Field and Mount Wiley in the White Mountains of New Hampshire (James brought up the rear). James and Alice eventually moved to Drexel, PA and were vacationing in Lake Placid in July of 1957 when James died unexpectedly at the age of 88. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

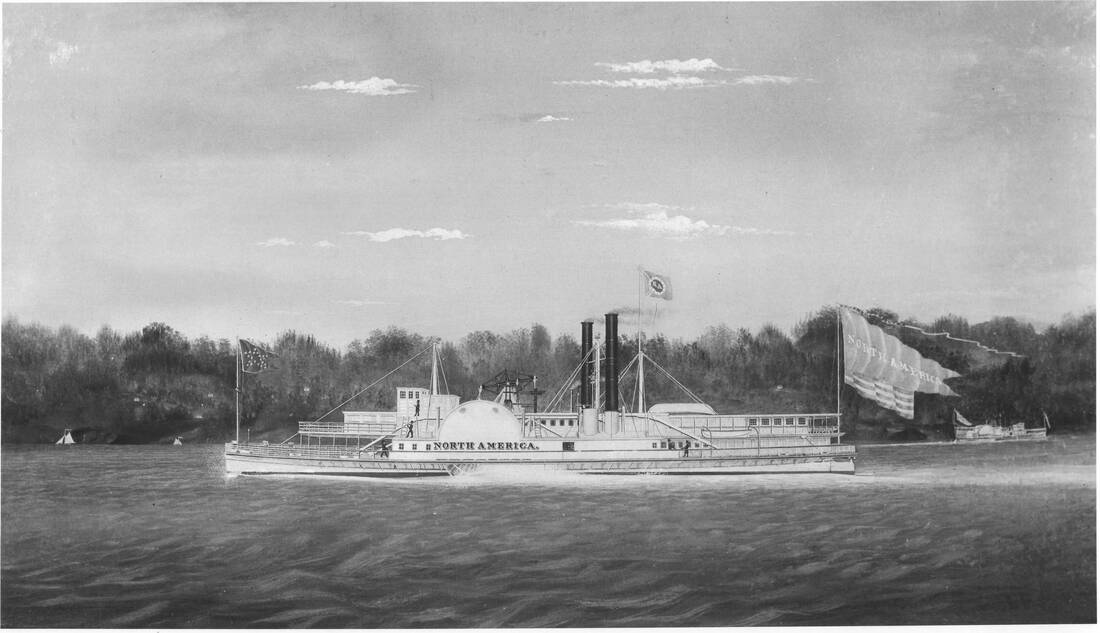

Editor's note: "Three Years in North America" by James Stuart, Esq. was originally published as a two volume travelogue in Edinburgh, Scotland in 1833 describing a journey taken in the late 1820s. In this section the British travelers describe meals on the steamboat "North America" as they travel up the Hudson River. Many thanks to volunteer researcher George M. Thompson for finding and transcribing this historic travelogue.  Steamboat "North America" b/w photograph of painting by Bard Brothers. There were two steamboats named "North America". The one described in the travelogue is the first and ran for 10 years. This may be an image of the second "North America" built in 1839. Donald C. Ringwald Collection, Hudson River Maritime Museum (p. 40) The North America is splendidly fitted up and furnished; the cabinet work very handsome; the whole establishment of kitchen servants, waiters, and cooks, all people of colour, on a great scale. *** (p. 41) We had breakfast and dinner in the steam-boat. The stewardess observing, that we were foreigners, gave notice to my wife some time previous to the (p. 42) breakfast-bell at eight, and dinner-bell at two, so that we might have it in our power to go to the cabin, and secure good places at table before the great stream of passengers left the deck. Both meals were good, and very liberal in point of quantity. The breakfast consisted of the same article that had been daily set before us at the city hotel, with a large supply of omelettes in addition. The equipage and whole style of the thing good. The people seemed universally to eat more animal food than the British are accustomed to, even at such a breakfast as this, and to eat quickly. The dinner consisted of two courses, 1. of fish, including very large lobsters, roast-meat, especially roast-beef, beef-steaks, and fowls of various kinds, roasted and boiled, potatoes and vegetables of various kinds; 2. which is here called the dessert, of pies, puddings, and cheese. Pitchers of water and small bottles of brandy were on all parts of the table; very little brandy was used at that part of the table where we sat. A glass tumbler was put down for each person; but no wine-glasses, and no wine drank. Wine and spirits of all sorts, and malt liquors, and lemonade, and ice for all purposes, may be had at the bar, kept in one of the cabins. There is a separate charge for every thing procured there; but no separate charge for the brandy put down on the dinner-table, which may be used at pleasure. The waiters will, if desired, bring any liquor previously ordered, and paid for to them, to the dining-table. p. 43 Dinner was finished, and most people again on deck in less than twenty minutes. They seemed to me to eat more at breakfast than at dinner. I soon afterwards looked into the dining-room, and found that there was not a single straggler remaining at his bottle. Many people, however, were going into and out of the room, where the bar is railed off, and where the bar-keeper was giving out liquor. The men of colour who waited at table were clean-looking, clever, and active, -- evidently picked men in point of appearance. We had observed a very handsome woman of colour, as well dressed, and as like a female of education, as any of those on board, on deck. My wife, who had some conversation with her, asked her, when she found that she had not dined with us, why she had not been in the cabin? She replied very modestly, that the people of this country did not eat with the people of colour. The manners and appearance of this lady were very interesting, and would have distinguished her anywhere. James Stuart. Three Years in North America. Vol. 1. Edinburgh, 1833. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Today's Media Monday post is all about extremely cold wintry conditions on the Hudson River in 1934, featuring footage of the Tarrytown (a.k.a. Sleepy Hollow) Lighthouse! This short film from British Pathe/Reuters features aerial footage of New York City and the Lower Hudson. The cold snap was deadly, as outlined below. On February 9, 1934, the New York Times reported on the record-breaking subzero temperatures, writing "At Tarrytown, powerful government tugs pounded at the ice that had formed in the harbor. They were trying to open a lane for lighters on which several hundred automobiles from the plants of the Chevrolet and Pontiac companies had been loaded for transport to New York. The Cars were destined for shipment to Europe. The ice in the harbor was more than fourteen inches thick and the tugs were unable to smash their way through." On February 10th, the Times published an article entitled, "Mercury 14.3 Below Zero on New York's Coldest Day: Six Dead and Hundreds Treated for Frostbitten Ears and Noses - 8-10 Below Due Here Today." Hundreds of school children needed to be treated for frostbite, six people died in their homes or on the streets due to the cold weather, and dozens of people suffered from carbon monoxide poisoning while trying to heat their vehicles in closed garages (none died). Snow removal efforts were halted due to the extreme cold, fire hydrants froze, and evictions were postponed. In maritime news, the Times reported, "The Coast Guard ice breaker AB-24 found the ice in the Great South Bay too strong even for her sharp prow. Hempstead Harbor also was icebound, causing some concern to industries there dependent on water carriers for supplies. The Bronx and Passaic Rivers were frozen solid and in the later fifty small craft were in danger of being crushed by the ice. In the Poconos and in New Jersey the finest supplies of ice in years were reported but - it was too cold for men to cut it." By February 11, 1934 the temperatures rose to more seasonal just-below-freezing, but 1934 remained one of the coldest winters on record for New York City. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's Note: The following is a verbatim transcription of a chapter from Spalding's Winter Sports by James A. Cruikshank, published in 1917 and part of the Ray Ruge Collection at the Hudson River Maritime Museum. Many thanks to volunteer Adam Kaplan for transcribing this booklet. The Canadians, winter lovers that they are, have given the world one of its finest implements for winter sport in the light, dainty, and marvelously swift toboggan. Probably no device of equal weight ever invented by man has attained such speed with such a load of valuable human lives. And when the end of the run is reached the thing can be picked up, tucked under an arm and carried back to the starting point; in fact that is the way in which many of the toboggans are returned to the starting point of some of the greatest runs in the world. “Zit! Walk a mile!” said a traveled Chinaman in describing his first impression of the sport. The strictly Canadian model toboggan is now made in the United States as well as in Canada. There have been practically no changes in the design which the Dominion first chose for the famous slides at Mount Royal, Montreal, Quebec, or Ottawa. Since the Indian fashioned the first toboggan with which to drag his winter’s catch of furs out to the nearest Hudson Bay post, the method of construction has changed but little. The uses of the frail chariot are distinctively different, however; now it serves to convey precious freight of charming, red-cheeked women down precipitous artificial slides on pleasure bent, where once it stood for carry-all and moving van for the taciturn nomads of the great white silences. Basswood or ash strips, from four to ten in number, are used in making a toboggan. The length may be anywhere from 5 to 9 feet and the bottom may be either flat, or there may be runners of wood or steel, usually three in number. Steel shod toboggans are a comparative novelty and fitted only for slides where ice is used; they are barred on many slides, owing to their speed, and they are not adapted to general use on snow. Toboggans can be successfully used on ordinary natural slides found on snow clad hillsides, either on crusted snow or even on loose snow if it is sufficiently packed. But the customary use of the toboggan is now found on artificial slides, or slides in which the natural slope of the land is combined with an artificial starting incline. Many country clubs have erected such slides, the most famous being that erected by the Ardsley Country Club, Ardsley, N.Y. Another very interesting illustration of how natural and artificial conditions may be combined to furnish a successful field for this fine sport, is found in the arrangement which prevails at the Lake Placid Club, Essex County, N.Y. This famous Adirondack club may be said to be a pioneer in winter sports, since it has been serving its members with such entertainment during every winter since 1902. The toboggan slide here starts from the roof of the golf house, an effective and novel way of getting immediate elevation for a good start, and the run is over a quarter of a mile in length with a drop of 114 feet. The slide at Quebec, which starts from the Citadel and runs down to the Dufferin Terrace, in front of the magnificent Chateau Frontenac, is the best illustration of a wholly artificial slide in this country or perhaps in the world. There are many private artificial toboggan slides in the United States, one of the most successful being that on the property of Mr. George D. Barron, Rye, N.Y., which was erected for the pleasure of his two daughters. The framework is of steel; a drop of nearly 70 feet is attained before the level of the field is reached and then the slide runs off in a board trough until it comes to a spreading meadow. The slide at the Ardsley Country Club, Ardsley, N.Y., has been extremely successful and has been liberally copied elsewhere. Here the plan of renting the privilege of using the slide for less than a dollar an hour per person has been the means of paying the entire cost of the experiment besides furnishing great sport for the members and their friends. Wherever possible the Canadian plan of having at least two slides side by side, separated by a snow bank of about a foot in height, will be found to greatly add to the interest. Toboggans can then be started simultaneously and the zest of competition in speed added to the thrill of swift descent. On the Mount Royal slide in Montreal there are five slides along each other, and when five toboggans loaded to their capacity start at once the sport is fast and furious. It is important that no toboggan be started on any slide until the party ahead sic seen to be out in the open field or free from possible collision. The bob-sled or “double runner” consists of fastening together two low sleds by means of a board. The cost of such an outfit ranges from five to five hundred dollars, and the five dollar rig will give almost as much sport as its expensive cousin. Steering is done by means of a wheel, like an automobile, controlling the front sled, or by means of ropes run through pulleys and held in the hand; this latter is the custom on Swiss slides. There are very few natural slides adapted to the bob-sled in this country, although there is great sport every winter in the competitions held between the coasting teams of several towns on Long Island, N.Y., and there is no reason why the sport should not become widely popular where towns are willing to devote certain roads or streets to the sport, as they do abroad. Handsome bob-sleds, cushioned in velvet and steered like a motor car, are drawn by horses and are capacious enough to carry twenty or more persons. The greatest bob-sled sport in the world is found on the famous “Cresta Run” in St. Moritz, Switzerland, or the equally famous “Kloster Run” in the town of Davos, Switzerland. Both of these wonderful coasts are over two miles in length, are on ordinary post roads set aside for the sport at certain seasons, and attract thousands of visitors from all over the world. Usually there is plenty of snow during the winter season at these resorts; when there is, the courses are built up at certain curves with great embankments of snow on which water is sprayed and then the resulting ice makes the course for much of its length a sheet of glass. At all intersecting roads there are danger signals set as the coaster starts from the top, and even the mail sleighs respect the sport. Speed of over ninety miles an hour is made on certain parts of these runs. The “Cresta Run” is regarded as the most difficult and the most interesting; one place in it known as the “Battledore and Shuttlecock” is probably the most superb piece of coasting ever built. At the close of the run there is a wonderful leap through the air which carries sled and rider 50 to 60 feet. The start and finish are timed by threads broken by the sled which thereby starts and stops a timing clock. Single sleds, of the pattern known to Americans as skeleton or clipper sleds, are generally used, having steel runners, open sides and big cushions set well back toward the end of the seat. Bob-sleds are also used on some of these runs and are occasionally steered by women. Pet dogs can be trained successfully to drag small toboggans or sleds just as the famous “huskie” dogs of Alaska do. The use of dogs for dragging snow vehicles is by no means limited to the wild wastes of Alaska, however. There are many dogs so used in the Adirondacks and in Canada. The famous dog team owned by Lord Minto, which was kept in Quebec several winters, was the means of initiating thousands of Americans into the sport of Dog Sledding. And the world famous races of dog teams dragging great loads, which Jack London has immortalized in his dramatic stories of the far north, are recalled by every lover of winter life in the silent places. A small dog sled is useful not merely as a vehicle for dogs to drag; it is the easiest way for man to carry any considerable load. The simplest pattern is a flat toboggan, generally of three strips of very thin basswood, ash or cedar, and in the case of the Indian made type is put together entirely without nails or screws of any kind, rawhide thongs taking their place. A one-man toboggan should not be over 4 feet in length and about 12 to 14 inches wide at the front and 2 inches narrower at the tail. The Indians make such a toboggan, and of this size, which weighs less than 3 pounds. A very simple and very efficient sled for either man or dog to drag is made from a couple of barrel staves on which a flat board is fastened in such fashion as to permanently preserve the full bend of the staves, then a back piece is fastened at right angles to the bottom board and braces run from the front of the bottom board to the top of the back board. A cross piece should be fastened at the front end of the staves and on this a whiffletree can be set; not until a man tries dragging a load with and without a whiffletree does he realize its value. AuthorJames A. Cruikshank was an expert on outdoors sports during the first half of the 20th century. Born in Scotland but spending most of his life in New York, he was the editor of The American Angler magazine, Field and Stream, and wrote numerous articles for a wide variety of other magazines and newspapers throughout his career, including the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. He also published at least three books: Spalding’s Winter Sports (1913, 1917), Canoeing and Camping (1915), and Figure Skating for Women (1921, 1922). He also contributed a chapter on artificial lures to The Basses: Freshwater and Marine (1905). In addition to his writing, Cruikshank was involved in public speaking, doing talks on outdoor sports sometimes illustrated by motion pictures. An avid photographer, Cruikshank’s photos often featured in his illustrated lectures, his articles, and his books, as he encouraged readers to take their own cameras out-of-doors. He had a home in the Catskills as well as a home and offices in New York City, and in the 1930s he helped found the Hudson River Yachting Association. At one point, he managed the Rockefeller Center ice skating rink, and another in Rye, NY. His wife Alice was also an avid camper and hiker, and they often traveled together. In 1909, Alice went “viral” in newspapers around the country by being the first person to blaze a trail between Mount Field and Mount Wiley in the White Mountains of New Hampshire (James brought up the rear). James and Alice eventually moved to Drexel, PA and were vacationing in Lake Placid in July of 1957 when James died unexpectedly at the age of 88. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

In May of 2022, the Hudson River Maritime Museum will be running a Grain Race in cooperation with the Schooner Apollonia, The Northeast Grainshed Alliance, and the Center for Post Carbon Logistics. Anyone interested in the race can find out more here. Moving food is important, as we've mentioned here before. Without food movement, people will starve, and without near-carbonless food movement, the world's efforts at climate change mitigation are likely to fail. One of the ways to move food with little to no carbon is through Sail Freight, which is a fitting subject for a maritime museum to talk about. So, what would a Sail Freight Future look like? We can take some clues from the past, of course, about how a sail freight future might look. In this case, we can see rivers and coastlines dotted with the image of sails and ships at harbor, moving large amounts of cargo between the countryside and cities, and between cities themselves. We can see thousands of supporting jobs building and maintaining ships, making sails, ropes, tar, and pitch, and fittings for keeping ships underway. However, those clues from the past are unlikely to give us an accurate idea of what we will need and can accomplish in a future of sailing cargo. First, we can’t simply revert to the past as the climate changes. Doing so is impossible, and shouldn't be desirable to begin with. Second, we now know more about the world than we did in the past, and can incorporate new sustainable technologies into modern sail freight. Our focus today will be reason number three: The world has significantly changed since Sail Freight was last common in the 1920s, and is now absolutely dependent on fossil fuels in both transportation and food production. In a sail freight future, we will need to have a food system which is capable of dealing with the realities of sail freight, which include less precise timing of deliveries, longer travel times, and in many areas a seasonality currently unknown. Less precise timing of deliveries means warehousing will have to come into more prominent use in the food system nearer to the point of end use for far more than just food. With a warehouse capable of holding several months' supplies, if a shipment is delayed due to contrary winds or a storm, no one goes hungry. The current practices of Just-In-Time delivery will have to be significantly changed, and the growth in warehouse jobs will likely be significant. Longer travel times for foods also means certain foods might become less available in certain regions, leading to a re-regionalized diet. For example, the ability to import fresh avocados and lemons in winter to Maine or New York might not be possible. The same would go for tomatoes from California or strawberries from Florida. Since these foods would not be likely to make the journey in their fresh forms, other forms such as preserves, juices, dried foods, and others will take their place. Canned and Jarred versions of these products will likely come more into play, and localized production using innovative techniques will be important. Lastly, the issue of seasonality fits into both of the above. For harbors with ice in parts of the year, warehouses will need to be big enough to hold the iced-in season's food needs for an area without resupply by water in that time frame, unless other carbon-neutral overland transport capabilities are available with the energy to operate them. The types of foods stored will have to be nonperishable, and storage will need to be properly designed for the environment. For an example of the other changes which would need to be made for a Sail Freight Future, the sheer number of ships and crew members needed is significant. For just the minimum grain and potato supply of the New York Metro Area, the estimated fleet would need to be 1,357 ships with a cargo capacity of 111.25 tons each, and nearly 9,000 sailors. While larger ships would likely be more efficient in crew, this is not guaranteed. When adding all this up, a fleet of these ships which could supply the New York Metro Area's food needs could be built using all the shipyards in the US in a mere 20 years, if all these shipyards produced 4 ships per year. We would also need to train over 3,000 sailors each year to crew these ships. Clearly, then, we would need to make changes to our shipbuilding capacity, train more welders, shipwrights, and so on, as well as sailors and captains. Then, the building of warehouses and docks would require labor as well. The task is not a small one, nor easy; it is, however, still achievable if we put our minds, our money, and our backs to it. For those interested in foodsheds and local food systems, an excellent book is Rebuilding the Foodshed by Philip Ackerman-Leist. You can find more information on the Grain Race here. AuthorSteven Woods is the Solaris and Education coordinator at HRMM. He earned his Master's degree in Resilient and Sustainable Communities at Prescott College, and wrote his thesis on the revival of Sail Freight for supplying the New York Metro Area's food needs. Steven has worked in Museums for over 20 years. Tune in tonight for Steve's virtual lecture, "The History and Future of Grain Races!"

If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today! In honor of our upcoming lecture, "The History and Future of Grain Races," as well as our upcoming exhibit on sail freight (currently under development), we thought we'd share this amazing historical film featuring footage from the bark "Peking" (formerly at South Street Seaport, now returned to her native Germany) as it sailed around Cape Horn in 1929. The film is silent, but narrated by Captain Irving Johnson, who was aboard "Peking" during this voyage and took all of the film footage with a camera he had brought with him. He was only 24 at the time. Johnson continued a career as a sailor, and met his wife, Electa "Exy" Johnson, while working aboard a schooner bound for France. They married in 1932 and went on to circumnavigate the globe together, teaching young sailors, and writing several books, articles, and producing several films based on their adventures. Their papers are now held in the collection of Mystic Seaport. For a glimpse into the later sailing expeditions of Captain and First Mate Johnson, check out this wonderful story map put together by Mystic Seaport charting their 1956 circumnavigation aboard the brigantine "Yankee" with a student crew. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's Note: Editor's Note: The following is a verbatim transcription of a chapter from Spalding's Winter Sports by James A. Cruikshank, published in 1917 and part of the Ray Ruge Collection at the Hudson River Maritime Museum. Many thanks to volunteer Adam Kaplan for transcribing this booklet. Please also note, this historic book chapter contains damaging stereotypes of Indigenous people. Like most inventions having to do with physical comfort, probably the snowshoe was a lazy man’s gift to the race. We can imagine how he found that by bandaging boughs on his moccasins feet he could get about with less trouble than his fellows; the idea spread, the boughs took form, then webbing was run across bows of wood and the snowshoe came into being. Every locality has its own special snowshoe, ranging from the eleven foot models of the Alaskans to the flat boards with cross pieces of the Italian dwellers of the Apennines. And each special model, far from being just subject for ridicule by the folks of any other locality, proves itself to be peculiarly adapted to the needs of the place in which it is found. Therein lies the lesson of all the new implements of the now popular winter sports; they must be adapted to the special localities in which they are to be used or the fullest measure of sport cannot be had. The Indian of the north prefers black or yellow birch for the bows of his snowshoes. Failing that wood of the right quality he selects ash, out of which the best of the snowshoes sold in large cities are generally fashioned. The webbing is preferably of caribou hide, but as there is very little caribou hide available the webbing is generally made bow cow hide for the important center and lamb skin for the filling of toe and tail piece. Properly treated and regularly painted with a good varnish these materials are entirely satisfactory for the most critical of snowshoe users. As a matter of fact the best snowshoes today are made by white men, not by Indians, just as the white man has come to make better canoes than the Indian ever made. The snowshoes sold at fair price by the leading dealers are thoroughly equal to any service they could be asked to give and will outwear several pairs of the Indian make. The webbing of the center is carried around the bow of the snowshoe, while that of the toe and tail is passed through small holes bored in the bow. Where the webbing is passed through the bows, little knots of worsted are used to break the knife-like cut of the crusted snow- not because they look pretty, as many folks think. The making of a pair of snowshoes takes the best part of several days, even with the aids of civilization, while among the Indian tribes of the far north several months elapse between the time when the first tree was felled for the bows to the day of the finished product, including stretching of the skins, warping of the bows, lacing of the webbing and drying out. The size of the snowshoe as well as its pattern depends largely upon the size and weight of the wearer, and the uses to which the snowshoe is to be put. For racing purposes the Alaskans use a snowshoe of 11 feet in length. The Montagnais beaux use a snowshoe of 36 inches in width. The trappers of the Rocky Mountains use a small “bear paw” snowshoe almost round in shape, and the best general snowshoe for the eastern part of the North American continent is the Algonquin or “club” pattern ranging from 40 to 50 inches in length and from 12 to 14 inches in width. The “bear paw” pattern is excellent for brush and hill country. The size of the mesh is governed by the average quality of the snow; when the snow is fine and dry and feathery a small mesh is desirable, while in damp and moist snow the mesh should be larger. Fastening the snowshoe to the foot is an important matter. Even the Indians and the trappers of the far north wanted to borrow or buy the ingenious American snowshoe sandal which I had attached to my snowshoes during a recent winter wolf hunting trip. These firm practical bindings are far and away superior to the lamp-wicking thongs or leather strings formerly used, especially when the walking is over hilly country, and the sag of the binding causes slipping of the foot on the snowshoe. Moccasins should be worn with snowshoes; dry tanned when the weather is very cold, say about zero, and oil tanned when it is warmer and the snow melts during the day. The binding should not be so tight as to stop the circulation nor should it come above the toe joints. An excellent device popular with the Appalachian Mountain Club of New England, on its winter outings on snowshoe, consists of a leather piece about the size of the foot attached to the under side of the snowshoe and studded with long pointed hob nails for ice creeping. There will often be times when some such device will be of the greatest value, especially in climbing crusted hillsides. The leather can be permanently attached to the snowshoe or merely tied on with rawhide thongs so as to be detachable if one wants to coast down hill on the snowshoes or does not require the additional grip on the snow. Almost anybody can learn to use snowshoes with little trouble. An hour will generally suffice the average athletic young person in which to secure sufficient ease in the use of the new toys to warrant starting off on a trip of a day or more. There are certain muscles which the sport calls into play, such as the upper thigh and the lower calf, that some folks have allowed to become weak and almost useless, but after a few days of Snowshoeing these muscles will learn their right function and cause little trouble. Correcting a wrong impression, it should be stated that the snowshoe does not really keep the walker on the top of the snow. When the snow is fine and the weather cold the snowshoe will sink in from two to five inches below the surface of the snow and the next step requires that it be lifted above the level of the snow and dragged along. This is the work which many beginners find most tedious and exhausting. The best way to save the strength of the beginners in such case is for the experts, whose muscles for the sport are in good trim, to “break trail” most of the time, thus reducing the work of the others who follow. But of course all plucky students of the sport will want in time to do their full share of the pioneering work of the leader. When the sport has been fairly learned, it is amazing how easy it becomes. Greater distances can be traveled on snowshoes in a day than any member of the party could walk on a macadamized road. This is due partly to the increased length of the stride, and partly to the easy cushion on which the foot comes to rest. Fifty and sixty miles is not an unusual day’s run for the expert snowshoer of the north. Thirty will be a good day’s work for the amateur, even after some years of experience. If packs of any kind are carried they should be of the Alpine ruck-sack pattern, consisting of a sort of loose knapsack swung over both shoulders and resting low in the back, so as not to interfere with the balance. A moonlight snowshoe walk over the hills such as is customary in Canada or in the Adirondacks, to a rendezvous where open fires are provided, either indoors or out, and hot meals are served, is a journey never to be forgotten. One of the special delights of such a party is the “Grand Bounce” which consists of tossing some member of the party into the air from the center of a blanket, the edges of which are held by a score of friends. Sometimes the blanket is dispensed with and the member thus “honored” is flung up by catching hold of arms and legs and body. One of the most famous of the pictures of this sport shows the late Frederick Remington being thus flung heavenward by his admiring friends. No sport of all the winter combines such a variety of picturesque costumes or such an international array of suitable material for the sport. For instance, the red and white and parti-colored blanket costumes are strictly Canadian in origin and history; the stockinette caps or toques are French; the socks, which are as indispensable as the snowshoes themselves, are German; the moccasins are Indian and the snowshoes, nine chances to ten, are American! AuthorJames A. Cruikshank was an expert on outdoors sports during the first half of the 20th century. Born in Scotland but spending most of his life in New York, he was the editor of The American Angler magazine, Field and Stream, and wrote numerous articles for a wide variety of other magazines and newspapers throughout his career, including the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. He also published at least three books: Spalding’s Winter Sports (1913, 1917), Canoeing and Camping (1915), and Figure Skating for Women (1921, 1922). He also contributed a chapter on artificial lures to The Basses: Freshwater and Marine (1905). In addition to his writing, Cruikshank was involved in public speaking, doing talks on outdoor sports sometimes illustrated by motion pictures. An avid photographer, Cruikshank’s photos often featured in his illustrated lectures, his articles, and his books, as he encouraged readers to take their own cameras out-of-doors. He had a home in the Catskills as well as a home and offices in New York City, and in the 1930s he helped found the Hudson River Yachting Association. At one point, he managed the Rockefeller Center ice skating rink, and another in Rye, NY. His wife Alice was also an avid camper and hiker, and they often traveled together. In 1909, Alice went “viral” in newspapers around the country by being the first person to blaze a trail between Mount Field and Mount Wiley in the White Mountains of New Hampshire (James brought up the rear). James and Alice eventually moved to Drexel, PA and were vacationing in Lake Placid in July of 1957 when James died unexpectedly at the age of 88. Tune in next week for the next chapter!

If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today! Editor’s Note: The following text is a verbatim transcription of an article featuring stories by Captain William O. Benson (1911-1986). Beginning in 1971, Benson, a retired tugboat captain, reminisced about his 40 years on the Hudson River in a regular column for the Kingston (NY) Freeman’s Sunday Tempo magazine. Captain Benson's articles were compiled and transcribed by HRMM volunteer Carl Mayer. See more of Captain Benson’s articles here. This article was originally published January 21, 1973. Back around 1908, there was a stone quarry at Rockland Lake south of Haverstraw and the Cornell Steamboat Company towed the quarry's scows to New York from early spring until hindered by ice the following winter. At the same time, the steamers "Homer Ramsdell" and "Newburgh" of the Central Hudson Line were carrying milk on a year round basis between Newburgh and New York. In early January of that long ago time, the Cornell tugboats "Hercules" and "Ira M. Hedges" were sent up river to the quarry to bring down five loaded scows of stone. Ice had been forming in the river and, as any man who has worked on the river soon finds out, the river sometimes closes over night. He also discovers that at times salt water ice is harder to get through than fresh water ice. When the tugs arrived at Rockland Lake, the river was covered with ice from shore to shore and making more ice rapidly. It was now about 5 p.m., very dark with a northeast wind, and it looked as if a storm was brewing. Captain Mel Hamilton of the "Hercules" telephoned Cornell's New York office and suggested they stay there overnight. He knew by waiting until daylight to start down, he could better find open spots in the floating ice and that the "Ramsdell" and "Newburgh" on their milk runs would be breaking up ice and perhaps keep it moving. The Cornell office, however, would not listen to Captain Hamilton's suggestion and told him they wanted him to start out immediately and get the tow to New York as soon as possible. Trouble at Tarrytown On leaving Rockland Lake with five wooden scows, the "Hercules" was in charge of the tow and the "Hedges" was supposed to go ahead and break ice since she had an iron hull. The ebb tide was about half done and everything went all right until they were about two miles north of the Tarrytown lighthouse. The "Hedges” wasn’t too good as an ice breaker and she would get fast in the ice herself. The "Hercules" with the tow would creep alongside and break her out. After this happened a few times, both tugs tried pulling on the tow. Finally, the tide began to flood, jamming the ice from shore to shore, and the two tugs couldn't move the tow at all through the ice. The only thing to do was to lay to until the tide changed. After about an hour it started to snow from the northeast and the wind increased to about 20 m.p.h. Captain Hamilton of the "Hercules" told Captain Herb Dumont of the "Hedges” to go back to the tail end of the tow and keep an eye out for the "Newburgh" he knew would be coming down. The "Hercules" lay along the head of the tow on watch for the ‘"Ramsdell" on her way up river. Both tugs started to blow fog and snow signals on their whistles, as they lay in the channel and knew the Central Hudson steamers would be going through the ice and swirling snow on compass courses at full speed in order to maintain their schedule and not expecting to find an ice bound tow in their path. Neither tugboat captain relished the thought of his tug or the tow being cut in half by the "Ramsdell" or "Newburgh." “Newburgh” Heard First The first of the two Central Hudson steamers to be heard was the "Newburgh” by the crew of the "Hedges." Coming down river with the wind behind her, the men on the tug could hear the "Newburgh" pounding and crunching through the ice and her big base whistle sounding above the storm. Both the "Hercules" and "Hedges" were blowing their whistles to let the "Newburgh" know they were fast in the ice and not moving. The snow storm had now become a blizzard. On the "Hedges" at the tail end of the tow, her crew was relieved when they could hear the crunching of the ice seem to ease off, indicating the "Newburgh" had probably heard their whistle and was slowing down. In a few moments, the bow of the "Newburgh" loomed up out of the blowing snow headed almost directly for the "Hedges." Above the storm, the men on the tugboat could hear the bow lookout on the "Newburgh" yell to the pilot house, "There's a Cornell tug dead ahead." The "Newburgh'' eased off to starboard and crept up along side of the tow. When abreast of the "Hercules," the captain, Jim Monahan, hollered through a megaphone to the "Hercules" captain, asking if he wanted "Newburgh” to circle around the tow and try and break them out of the ice’s grip. Boatmen always tried to help one another out, even though they might have been working for different companies. Moved and Stopped The "Newburgh" cut around the tow twice before continuing on her way to New York and disappearing into the swirling snow of the winter's night. The "Hercules" was able to move the tow about one tow’s length and was then again stopped. In about half an hour, the crew of the "Hercules” could hear the whistle of the "Homer Ramsdell" blowing at minute intervals as she was cutting through the ice on her way to Newburgh. On the "Herc," they were sounding her high shrill whistle to let the "Ramsdell" know they were in the channel. In those days, long before the radio telephones of today, the steam whistle signals were the boatman's only means of communication. The "Ramsdell" came up bow to bow with the "Hercules," backing down hard, the bow lookout yelling to the pilot house a tow was ahead. Coming to a stop with only a few feet separating the two vessels, Captain Fred Miller of the "Ramsdell" tramped out on his bow and yelled down to Captain Hamilton, asking if he could be of any help. When told the tow was fast in the ice, Captain Miller said he was ahead of time and would try and free the tow. Captain Miller took the "Ramsdell" around the tow twice and then continued on his way up river. This time, the "Hercules" was able to move the tow about two tow lengths and again came to a dead stop. All they could do now was wait for the tide to change. However, at least they knew no other steamers were moving on the river and they were relatively safe. Leaks Develop When the crew of the "Hercules" was sitting in the galley and having a cup of hot coffee, one of the scow captains hollered over and waving a lantern, said his scow was leaking and his pumps were frozen. Men from the "Hercules" then had to climb over the snow covered scow and try to find and stop the leak. One of the deckhands found the leak in the dark and patched it up. After about two hours, the same thing happened to another scow, the oakum having been pulled out of the seams at the water line by the ice. Finally, the tide began to ebb again and they were able to once again move the tow. Shortly after daylight the snow storm abated and the wind moderated. As the "'Hercules" and the "Hedges" moved further down river, the ice became more floes than solid ice. However, before arriving in New York, they were overtaken by the "Ramsdell" again the following night off Manhattanville. After the crews’ long battle with ice and snow and on arriving in New York, their reward was to have their tugs tied up and to be layed off for the winter. In those days their pay was extremely modest. As a matter of fact, the pay of deckhands and firemen was a bunk, food and a dollar a day, — for a twelve hour day, seven days a week. As the boatmen used to say. "Thirty days and thirty dollars." AuthorCaptain William Odell Benson was a life-long resident of Sleightsburgh, N.Y., where he was born on March 17, 1911, the son of the late Albert and Ida Olson Benson. He served as captain of Callanan Company tugs including Peter Callanan, and Callanan No. 1 and was an early member of the Hudson River Maritime Museum. He retained, and shared, lifelong memories of incidents and anecdotes along the Hudson River. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

The winter of 1934 was a particularly bad one for New York and most of the Northeast. We'll be learning more about the record-breaking temperatures in subsequent posts, but check out this footage of the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter "Manhattan" breaking ice up the Hudson River in 1934. There have been several U.S. Coast Guard vessels named "Manhattan," the first of which was built in 1873. It's not clear if the replacement "Manhattan" was built in 1918 or 1921, but that is likely the vessel shown in this film. The second "Manhattan" was decommissioned and sold in 1947, her ultimate fate unknown. The SS "Manhattan" was another famous ice breaker. Originally built as an oil tanker, she was the first commercial vessel to successfully navigate the Northwest Passage in 1969. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

|

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 [email protected] Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |