History Blog

|

|

|

|

|

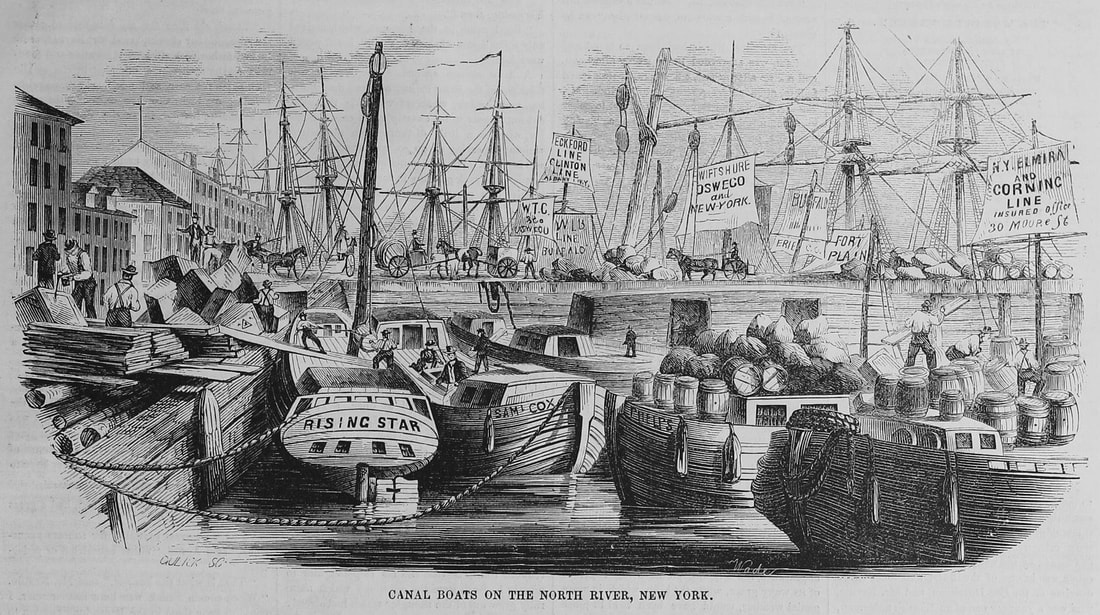

Editor's note: The following excerpts are from the January 3, 1875 issue of the "New York Times". Thank you to Contributing Scholar George A. Thompson for finding and cataloging this article. The language, spelling and grammar of the article reflects the time period when it was written. Loading Her Up. Scenes on the Docks. The Shipping Clerk – The Freight – The Canal-Boat Children. I am seeking information in regard to the late 'longshoremen's strike, and am directed to a certain stevedore. I walk down one of the longest piers on the East River. The wind comes tearing up the river, cold and piercing, and the laboring hands, especially the colored people, who have nothing to do for the nonce, get behind boxes of goods, to keep off the blast, and shiver there. It was damp and foggy a day or so ago, and careful skippers this afternoon have loosened all their light sails, and the canvas flaps and snaps aloft from many a mast-head. I find my stevedore engaged in loading a three-masted schooner, bound for Florida. He imparts to me very little information, and that scarcely of a novel character. "It's busted is the strike," he says. "It was a dreadful stupid business. Men are working now at thirty cents, and glad to get it. It ain't wrong to get all the money you kin for a job, but it's dumb to try putting on the screws at the wrong time. If they had struck in the Spring, when things was being shoved, when the wharves was chock full of sugar and molasses a coming in, and cotton a going out, then there might have been some sense in it. Now the men won't never have a chance of bettering themselves for years. It never was a full-hearted kind of thing at the best. The boys hadn't their souls in it. 'Longshoremen hadn't like factory hands have, any grudge agin their bosses, the stevedore, like bricklayers or masons have on their builders or contractors. Some of the wiser of the hands got to understand that standing off and refusing to load ships was a telling on the trade of the City, and a hurting of the shipping firms along South street. The men was disappointed in course, but they have got over it much more cheerfuller than I thought they would. I never could tell you, Sir, what number of 'longshoremen is natives or aint natives, but I should say nine in ten comes from the old country. I don't want it to happen again, for it cost me a matter of $75, which I aint going to pick up again for many a month." I have gone below in the schooner's hold to have my talk with the stevedore, and now I get on deck again. A young gentleman is acting as receiving clerk, and I watch his movements, and get interested in the cargo of the schooner, which is coming in quite rapidly. The young man, if not surly, is at least uncommunicative. Perhaps it is his nature to be reticent when the thermometer is very low down. I am sure if I was to stay all day on the dock, with that bitter wind blowing, I would snap off the head of anybody who asked me a question which was not pure business. I manager, however, to get along without him. Though the weather is bitter cold, and I am chilled to the marrow, and I notice the young clerk's fingers are so stiff he can hardly sign for his freight, I quaff in my imagination a full beaker of iced soda, for I see discharged before me from numerous drays carboys of vitriol, barrels of soda, casks of bottles, a complicated apparatus for generating carbonic-acid gas – in fact, the whole plant of a soda-water factory. I do not quite as fully appreciate the usefulness of the next load which is dumped on the wharf – eight cases clothes-pins, three boxes wash-boards, one box clothes-wringers. Five crates of stoneware are unloaded, various barrels of mess beef and of coal-oil, and kegs of nails, cases of matches, and barrels of onions. At last there is a real hubbub as some four vans, drawn by lusty horses, drive up laden with brass boiler tubes for some Government steamer under repairs in a Southern navy-yard. The 'longshoremen loading the schooner chaff the drivers of the vans as Uncle Sam's men, and banter them, telling them "to lay hold with a will." The United States employees seem very little desirous of "laying hold with a will," and are superbly haughty and defiantly pompous, and do just as little toward unloading the vans as they possibly can thus standing on their dignity, and assuming a lofty demeanor, the boxes full of heavy brass tubes will not move of their own accord. All of a sudden a dapper little official, fully assuming the dash and elan of the navy, by himself seizes hold of a box with a loading-hook; but having assert himself, and represented his arm of the service, having too scratched his hand slightly with a splinter on one of the boxes, he suddenly subsides and looks on quite composedly while the stevedore and 'longshoreman do all the work. Now I am interested in a wonderful-looking man, in a fur cap, who stalks majestically along the wharf. Certainly he owns, in his own right the half-dozen craft moored alongside of the slip. He has a solemn look, as he lifts one leg over the bulwark of a schooner just in from South America, and gets on board of her. He produces, from a capacious pockets, a canvas bag, with U.S. on it, and draws from it numerous padlocks and a bunch of keys. He is a Custom-house officer. He singles out a padlock, inserts it into a hasp on the end of an iron bar, which secures the after-hatch, snaps it to, gives a long breath which steams in the frosty air, and then proceeds, with solemn mein, to perform the same operation on the forward hatch. Unfortunately, the Government padlock will not fit, and, being a corpulent man, he gets very red in the face as he fumbles and bothers over it. Evidently he does not know what to do. He seems very woebegone and wretched about it, as the cold metal of the iron fastening makes it uncomfortable to handle. Evidently there is some block in the routine, on account of that padlock, furnished by the United States, not adapting itself to the iron fastenings of all hatches. He goes away at last, with a wearied and disconsolate look, evidently agitating in his mind the feasibility of addressing a paper to the Collector of the Port, who is to recommend to Congress the urgency of passing measures enforcing, under due pains and penalties, certain regulations prescribing the exact size of hatch-fastenings on vessels sailing under the United States flag.  "Canal Boats on the North River, New York" by Wade, "Gleason's Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion," December 25, 1852. Note the sail-like signs for various towing lines and destinations, as well as the jumble of lumber and cargo boxes on the pier at left, waiting to be loaded onto the canal boats (or vice versa). I return to my schooner. By this time the wharf is littered with bales of hay, all going to Florida. I wonder whether it is true, as has been asserted, that the hay crop is worth more to the United States than cotton? I think, though, if cotton is king, hay is queen. Now comes an immense case, readily recognized as a piano. I do not sympathize with this instrument. Its destination is somewhere on the St. John's River. Now, evidently the hard mechanical notes of a Steinway or a Chickering must be out of place if resounding through orange groves. A better appreciation of music fitting the locality would have made shipments of mandolins, rechecks, and guitars. Freight drops off now, and comes scattering in with boxes of catsup, canned fruits, and starch. Right on the other side of the dock there is a canal-boat. She has probably brought in her last cargo. And will go over to Brooklyn, where she will stay until navigation opens in the Spring. There is a little curl of smoke coming from the cabin, and presently I see two tiny children – a boy and a girl – look through the minute window of the boat, and they nod their heads and clap their hands in the direction of the shipping clerk. The boy looks lusty and full of health, but the little girl is evidently ailing, for she has her little head bound up in a handkerchief, and she holds her face on one side, as if in pain. The little girl has a pair of scissors, and she cuts in paper a continuous row of gentlemen and ladies, all joining hands in the happiest way, and she sticks them up in the window. This ornamentation, though not lavish, extends quite across the two windows, the cabin is so small. Having a decided fancy, a latent talent, for making cut-paper figures myself, I am quite interested, as is the receiving clerk. I twist up, as well as my very cold fingers will allow, a rooster and a cock-boat out of a piece of paper, and I place them on a post, ballasting my productions with little stones, so that they should not blow away. The children are instantly attracted, and the little boy, a mere baby, stretches out his hands. My attention is called to a dray full of boxes, which are deposited on the wharf for our schooner. Somehow or other the receiving clerk, without my asking him, tells me of his own accord what they contain – camp-stools. I can understand the use of camp-stools in Florida: how the feeble steps of the invalid must be watched, and how, with the first inhalation of the sweet balmy air, bringing life once more to those dear to us, some loving hand must be nigh, to offer promptly rest after fatigue. I return to my post, but alas my rooster and cock-boat have been blown overboard; the wind was too much for them. I kiss my hand to the little girl, who smiles with only one-half of her face; the stiff neck on the other side prevents it. The little boy points to the post and makes signs for more cock-boats. Snow there happens to come along on that wharf an ambulant dealer with a basket containing an immense variety of the most useless articles. He has some of the commonest toys imaginable, selected probably for the meagre purses of those who raise up children on shipboard. There are wooden soldiers, with very round heads but generally irate expressions, and small horses, blood-red, with tow tails and wooden flower-post, with a tuft of blue moss, from which one extraordinary rose blossoms, without a leaf or a thorn on the stem. On that post for ten cents that ambulant toy man put five distinct object of happiness, when the shipping clerk interfered. "It's a swindle, Jacob," he said. That young man was certainly posted in the toy market along the wharves. "You ain't going to sell those things two cents a piece, when they are only a penny? You must be wanting to retire after first of the year. Bring out five more of them things. Three more flower-pots and two more horses. The little girl takes the odd one. What's this doll worth? Ten cents! Give you five. Hand it over. Now clear out. I see you, Sir, watching them children. Poor little mites. No mother, Sir. Father decent kind of fellow; says their ma died this Spring. Has to bring 'em up himself, and is forced to leave them most all day. He is only a deck-hand and will be the boat-keeper during Winter. Been noticing them babies ever since I have been loading the schooner – most a week – and been a wanting to do something for their New-Year's. A case of mixed candies busted yesterday, and they got some. They have been at the window ever since, expecting more; but nothing busted. You can't get in; the cabin is locked, but I can manage it through the window." So my young friend climbed on board, with the toys in his pocket, lifted up the sash, and passed through the toys one by one, the especial rights of proprietorship having been carefully enjoined. Presently all the soldiers and the follower-pots were stuck in the window, and the little girl was hugging the doll. "Loading her up; taking in freight for a vessel of a Winter's day on a wharf isn't fun," said the young gentlemen sententiously. "I shouldn't think it was," I replied. "In fact, there ain't much of anything to see or do on a wharf which is interesting to a stranger." "You are from the country, ain't you?" asked the young man with a smile. "Never seen New-York before? Wish you a happy New Year, anyhow." I did not exactly how there could be any reservation as to wishing me a happy New Year whether I was from the country or not, but supposing that this singularity of expression arose from the general character of the young man, or because he was uncomfortable from the frosty weather, I returned the compliment, inquiring "whether a stiff neck was not very hard on children," and not being a family man, added, "They all get it sometimes, and get over it, don't they ?" "It ain't a stiff neck, it's mumps. Mother sent me a bottle of stuff for the child three days ago, and her father has been rubbing it on, and she's most over it now. When I was a little boy," added the clerk reflectively, "toys cured most everything as was the matter with me." "Just my case," I replied, as we shook hands and I left the wharf. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

0 Comments

Editor's Note: The following text is a verbatim transcription of an article written by George W. Murdock, for the Kingston (NY) Daily Freeman newspaper in the 1930s. Murdock, a veteran marine engineer, wrote a regular column. Articles transcribed by HRMM volunteer Adam Kaplan. Oseola The steamboat “Oseola” was one of the Hudson river vessels which were in service in the early days of steam navigation on the river and were then taken to other rivers, passing from the pages of Hudson river steamboats. Records of river-craft contain little information about the “Oseola,” but one fact that is evident throughout the sparse recordings of this vessel was her ability to sail up and down the river at a faster pace than most of the other steamboats of her size at that particular time in the river’s history. The wooden hull of the steamboat “Oseola” was constructed by William Brown at New York in the year 1838. She was built for the celebrated Alfred DeGroot, at that period a brilliant figure in the activities of the Hudson river, and was scheduled for service on the waters discovered by Henry Hudson in his quest for a short route to India. Known to rivermen as one of the “clippers of her day,” the “Oseola” was placed in service between New York and Fishkill- running as a dayboat and making landings at intermediate points along the river. The only indication as to the size of the “Oseola” comes from a recorded observation that she was “one of the fastest small boats on the river,” but her actual dimensions have been lost in the maze of steamboat histories that have come down through the years of steamboat navigation. After making numerous trips on the New York-Fishkill route, the “Oseola” established a name for herself as a fast vessel, and her trips were extended up the river to Poughkeepsie. She plied the waters between New York and Poughkeepsie for the balance of her first season. In the spring of 1839 the “Oseola” was placed in service between the city of Hudson and New York, under the command of Captain Robert Mitchell. She left New York at the foot of Chambers street every Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday at four o’clock for Hudson, and made landings at Caldwell’s, West Point, Fishkill, New Hamburgh, Milton, Poughkeepsie, Hyde Park, Thompson’s Dock, Kingston, Red Hook, Bristol and Catskill. On her trip down the river the “Oseola” left Hudson every Monday, Wednesday and Friday morning at 6 o’clock, and made the same landings on her return trip. At Hudson she landed at the old State Prison wharf at the foot of Amos street where both freight and passengers were discharged or taken aboard. The steamboat “Oseola” plied the waters of the Hudson river for several years and was then taken to the Delaware river. The length of her service on the Hudson river, or how long her career continued. after she appeared on the Delaware river, is unknown, as the record of her service closes with her transfer to the Delaware river. AuthorGeorge W. Murdock, (b. 1853-d. 1940) was a veteran marine engineer who served on the steamboats "Utica", "Sunnyside", "City of Troy", and "Mary Powell". He also helped dismantle engines in scrapped steamboats in the winter months and later in his career worked as an engineer at the brickyards in Port Ewen. In 1883 he moved to Brooklyn, NY and operated several private yachts. He ended his career working in power houses in the outer boroughs of New York City. His mother Catherine Murdock was the keeper of the Rondout Lighthouse for 50 years. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's note: The following excerpts are from the "Jamestown (NY) Journal" 1858-1859.. Thank you to Contributing Scholar George A. Thompson for finding, cataloging and transcribing this article. The language, spelling and grammar of the article reflects the time period when it was written. How we smile now at the bungling expedient for rapid traveling that prevailed twenty years ago. By canal boats from Troy through the nine locks at a cent and a half a mile, and board yourself. By packet from Schenectady west, drawn by three horses, on a slow trot, and three days to Buffalo. And up and down yonder hill crept the first railroad, with cars hung on thoroughbraces, and seats for nine inside, and some outside, which were dragged up an inclined place one hundred and eight feet to the half mile, by a stationary engine, and then over the sand plains to the head of State street in Albany. And this was then such a triumph of engineering. What a change! where our fathers crept we fly. The mountains they climb, we tunnel. The hills they toiled up, we level, or divide by a deep cut, thrown arches over ravines at them impassible. . . . Jamestown Journal (Jamestown, N. Y.), July 16, 1858, p. 2 Correspondence of the Journal. VACATION LETTERS, . . . NO. 4. To New York over the Erie Rail Road -- Sleeping Cars -- New York to New Haven . . . . *** On arriving at Dunkirk, we boarded the Night Express, and took our seats in the luxuriously furnished sleeping car, determining to try the virtue of this boasted institution. Lodgings were furnished at 50 cents a man. My little girl who accompanied me was stowed in without extra charge. There were 40 berths in the car, four in each tier, one double birth at the bottom and two above. The upper berths were cane seated frames, the ends of which were fixed into sockets, while the bottoms of the lower were of wood. All were covered with nice hair mattresses, and pillows enclosed by damask curtains, making a very handsome appearance. About nine o'clock the chambermaid who was a buxom, round faced laddie [sic], made up the berths and we turned in. There were about thirty sleepers in the car. *** Think of sleeping in a car, rushing at the rate of thirty miles an hour, along the brink of lofty precipices, leaping black ravines, threading deep cuts, mounting lofty viaducts, and careering through some of the most splendid scenery in the world. ** Jamestown Journal (Jamestown, N. Y.), September 2, 1859, p. 2 [Editor's Note: He remembers the Green Mountains of his childhood] Yet when I visit that place it is all changed. The old forest is gone, the speckled trout have forsaken the pools; the streams are dried up, or flow in straight spade-cut channels, the roaring branch is trained through sluices, or broken over water-wheels. *** Jamestown Journal (Jamestown, N. Y.), July 16, 1858, p. 2 If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's note: The following are excerpts from NY Herald, September 7, 1857, p. 1, cols. 1-5 -- The New York Ferries. Thank you to Contributing Scholar George A. Thompson for finding, cataloging and transcribing this article. The language, spelling and grammar of the article reflects the time period when it was written. THE NEW YORK FERRIES. Visit of Inspection of One of the Herald Reporters to each Boat and Ferry Landing, and what he saw there -- Condition of Boats, and Means taken for Life Saving *** EAST RIVER. EIGHTY-SIXTH STREET OR HELL GATE FERRY. This ferry has but two boats, the Astoria, of 119 tons, built in 1840, and the Sunswick, of 129 tons, built in 1848. They are both built after the same primitive style of the Hoboken ferry boats. . . . *** Wednesday of every week this ferry is almost entirely converted into a cattle ferry, a large number crossing on almost every boat, which renders it anything but pleasant or agreeable for foot passengers. *** GREENPOINT, TENTH AND TWENTY-THIRD STREET FERRIES. THE TRIPS. The Tenth street ferry has two boats on from four o'clock in the morning until nine o'clock at night, so that one boat leaves the slip on either side of the river every ten minutes during those hours. From nine o';clock until quarter past one at night there is but one boat on, making twenty minute trips, after that hour, up to four o'clock in the morning, no boat runs. On the Twenty-third street ferry there is but one boat running from six o';clock in the morning up to ten o'clock at night, making fifteen minute trips. . . . THE LIGHTS. This company have set an example worthy of following by some of the other companies in respect to lighting their ferry slips, bridges and passenger ways at night, there being ten large gas lights inside of the ferry gates, two of them being at the end of each bridge. The boats all present a neat and clean appearance, the ladies cabins all being well cushioned. . . . *** Most of the business done by the ferry . . . is by the crossing of country wagons. . . . A very large number of funerals, also cross this ferry daily on their way to Calvary Cemetery. The foot passing over these ferries is as yet quite insignificant, owing in great measure to the fact that there is no shipbuilding or other mechanical business of any account going on at Greenpoint at present, and the fact that fever and ague abounds in the village of Greenpoint to a greater or less extent during the warm weather. HOUSTON STREET FERRY. *** The boats are usually kept in cleanly and comfortable condition, with the exception of lights in the cabins at night, which are very deficient, they being scarcely sufficient for passengers, sitting opposite each other to discern the precise complexion of their neighbor's countenance, much less to read by. . . . Two boats are kept running from five o'clock in the morning until ten o';clock at night. . . . After ten o'clock at night there is but one boat running until five in the morning. . . . *** PECK SLIP, DIVISION AVENUE AND GRAND STREET FERRIES. [Editor's Note: long discussion of the lack of accommodations] THE JAMES SLIP AND SOUTH TENTH STREET FERRY. [began running last May] The boats of this ferry are the "George Law", of 400 tons, one year old, and "George Washington", 400 tons, the same age, both of which are double decked, clean, commodious and well cushioned. *** The bridges on each side of the river are forty feet long, and thirty feet wide, on floats. The houses each have two fine sitting rooms for ladies and gentlemen, the seats in all of which are handsomely cushioned, the same as the ladies; cabins on the boats. *** The pilots employed on the boats of this company are quite too careless and reckless of human life. . . . *** UNION FERRY COMPANY. [Fulton Ferry: 4 boats; Wall street Ferry: 2 boats; Atlantic, or South street Ferry, 3 boats; Hamilton Avenue Ferry, 4 boats; Roosevelt street Ferry, 2 boats; Catherine street Ferry, 2 boats] *** South ferry run three boats every five minutes from 5 in the morning until 10 o'clock at night, and two up to 12 o';clock, after which there is one untill 5 in the morning. The Hamilton avenue ferry runs four boats during the day and one all night, as fast as they can be run. The Fulton ferry has four boats on all day and two on all night. The Catherine and Roosevelt street ferries have two boats on all day, and one all night at the Catherine ferry, and one on up to nine o'clock on the Roosevelt street ferry. The Wall street ferry has two boats on during the day, and one on from six in the evening until twelve at night, when both are drawn off until four o'clock in the morning. [a new boat is being built, that will have gas lights in the cabins] JERSEY CITY FERRY. *** [among the boats on this ferry is the] "John S. Darcy", built in 1857, tonnage 700, and one hundred horse poser engine. . . . This boat has just been put on the ferry, and is a perfect floating palace. She is lit up with gas, which is introduced in tanks . . . ; these tanks being filled and taken on board as often as necessary. *** Three boats are run on the Jersey city ferry from 4 o'clock in the morning until half-past 10 o'clock, making about ten minute trips. From half-past ten at night until four in the morning two boats are run, making half hour trips. THE HOBOKEN FERRIES. This ferry being the principal breathing outlet to the city, especially for women and children, who desire to take a sail during the warm weather, and the thousands who daily visit Hoboken, of all sexes and ages for pleasure, it is something to be regretted that the present owner of the several ferries, Edwin A. Stevens, Esq., does not take more active means to provide against any accident of emergency which is so liable to arise at any moment, especially on boats so continually crowded as those are with females and children. *** The following are the names and ages of the boats owned on these ferries: -- BARCLAY STREET FERRY James Watts, built in 1851, tonnage 312 31-95. Patterson, built in 1854; tonnage 360 62-95. CANAL STREET FERRY John Fitch, built in 1845, tonnage 125 75-95. CHRISTOPHER STREET FERRY Phoenix, registered in the custom house as Fairy Queen, built in 1826, and subsequently cut in two, and about 70 feet added to her middle. She is 141 81-95 tons burden. SPARE BOATS. Chancellor Livingston, built in 1852; tonnage 457 61-95. Newark, built in 1827; tonnage 175 17-95. Hoboken, built in 1822; tonnage 322 20-95 These boats are all built in the primitive style, with but one carriage way, and no separate passage for foot passengers. [their life boats] The John Fitch has a metallic life boat the proper length. The Hoboken, which issued on the Christopher street ferry as a cattle boat, is without any boat, corks, boat hooks, ladders, floats, or any conveniences whatever for saving life, with the exception of one old cork life preserver, hung on the upper deck. The boats on the Newark and Phoenix are miserable concerns and unfit for use. . . . Those on the other four boats are better, but not such as should be provided, with the single exception of the metallic boat. Each of the six boats, are otherwise supplied with from five to six cork buoys, only one of which on either boat is supplied with a lanyard, and one pike pole, all of which are kept tied to braces on the upper decks of the boat, and consequently would be of . . . little purpose . . . in the event of an unlooked for accident. . . . The Phoenix is said by those who should know to be unsafe, and entirely unfit for use as a ferry boat. *** The ferry bridges are for the most part swing bridges, the only suitable ferry house being that at the foot of Barclay street. On the Hoboken side carts and wagons are driven in every direction at hap hazard, inside of the gates promiscuously among the passengers, rendering it anything but agreeable or safe for foot passengers, especially during the busy portions of the day. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

|

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 [email protected] Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |