History Blog

|

|

|

|

|

Editor's note: The following text was originally published in an undated published booklet "Ice Yachting Winter Sailboats Hit More Than 100 m.p..h.. by John A. Carroll with additional information from the "New York Times" article from February 8, 1978. The language, spelling and grammar of the article reflects the time period when it was written. For information about current ice boating on the Hudson River go to White Wings and Black Ice here. Ice yachting easily qualifies as the fastest winter sport in the world. Skiing? The ice yacht moves twice as rapidly. Bob-sledding? Nearly 25 m.p.h. faster. And ice yachts, unlike bob-sleds, do not have brakes. According to Ray Ruge, president of the Eastern Ice Yachting Association, the world ice yacht speed record over a measured course with flying start stands at 144 m.p.h. At Long Branch, N.J., Commodore Elisha Price in Walter Content's "Clarel" set the mark in February 1908, by covering one mile in 25 seconds. The time was clocked by five stop watches. The speed has been exceeded unofficially on several occasions. "From - Feb 6, 1978 - New York Times: Outdoors: Slipping Silently over the Ice by Fred Ferretti: One of the first lessons taught when you take up the speedy and somewhat dangerous sport of iceboating is to watch out for Christmas trees. Christmas trees mark thin ice or ice that has holes in it, that is rough and heavily pitted or that is overlaid with an invisible layer of water. These hazards can be disastrous to the spruce or fiberglass boats that tear across frozen rivers and lakes, sometimes at speeds of more than 100 miles an hour." While speed records remain a goal for winter sailors, most American ice yachtmen now center their attention on competitive racing and the annual regattas that have become an important part of the cold weather sports scene. Keen spectator and participant interest in this old sport are comparatively recent developments. Ice yachting, of necessity, has a limited appeal. There are few sections in the country where cold weather and hard-frozen lakes make the sport practicable. Moreover, the high cost of constructing the large yachts popular at the turn of the century restricted the sport to the very wealthy. The weather factor has remained fairly constant and ice yachting still is confined to a few choice locations - mainly in the American-Canadian border states and provinces. However, the financial requirement has undergone a radical change. The organization of the International Skeeter Association in 1939 is, to a large degree, responsible for the current boom in the sport. The "Skeeters," which are limited to 75 square feet of sail and cost as little as a few hundred dollars to build, outraced the larger boats in most of last year's major regattas. Approximately 75 per cent of all present ice boat construction follows this design. There are still large boats on the ice, although initial building expenses and prohibitive transportation costs have held construction to a minimum during the last few years. The two largest yachts currently in active competition are “Deuce”, owned by Clare Jacobs of Detroit and piloted by Joe Snay of the same city, and “Debutante”, owned by the Van Dyke family of Wisconsin and skippered by John Buckstaff of Oshkosh. Both yachts carry 600 sq. ft. of heavy Wamsutta sail cloth, but the “Deuce” is the longer of the two. The Detroit yacht, which is a thing of picturesque beauty with its huge jib-and-mainsail rig, is 52 feet in length and carries a 52-foot high mast. Its solid, springy runner plank measures 30 feet across.  The Last of the Stern-Steerers: A starting lineup on Lake Winnebago at Oshkosh, Wisconsin. Left to right: “Debutante III”, Oshkosh I.Y.E., “Deuce”, Detroit I.Y.C. and “Flying Dutchman”, Oshkosh I.Y.E. Race won by “Deuce” shod with 8 ft. runners because of soft ice. Ray Ruge Collection, Hudson River Maritime Museum. To the non-scientist, it seems unbelievable that any craft backed only by a stiff wind, can hit 100 miles an hour or better. The secret is the reduction of surface friction to just a few inches of sharp steel runner slipping across the ice, plus the small air resistance offered by a streamlined fuselage. Once an ice boat gets underway, the friction becomes almost negligible. And the speed is created by a partial vacuum of air currents ahead of the sail which pulls the craft forward until the boat is traveling from three to six times the velocity of the wind. Little is known of the origin of ice boats, although it has been established that Scandinavians in the Middle Ages were using a workable craft. Chapman's "Architecture Navalis Mercatoria" of 1768 mentions the sport by describing an ice yacht with a converted hull, a cross piece and a runner at each end. The Poughkeepsie Ice Yacht Club, an organization leaning to men of wealth and leisure, was organized in 1861. Using large, expensive craft, the club members specialized in racing trains along the river banks. The engineer tooted the whistle and passengers cheered, as the yachtsmen accepted the challenge and a contest was on. At the turn of the 20th century, new and more complete organizations began to take place. In 1912, new sportsmen formed the Northwestern Ice Yachting Association at Oshkosh, Wis., to embrace clubs in 'the Illinois, Michigan and Wisconsin region. Sail expanse classifications were drawn up to promote competition. As interest in the sport drew and new boats were built in greater numbers, new classifications were established. The Northwestern Association now lists the following: Class A, up to 350 square feet of sail; Class B, up to 250; Class C, up to 175; Class D, 125; Class E, 75.  Sailing preparations are underway in the yacht basin at Hamilton, Ont., as enthusiasts ready their boats for the day's activity. Yachtsmen pray for blustery, windy weather to ensure higher racing speeds. The sport, which is aging in new followers every year, attracted an estimated 3,000 participants this winter. Ray Ruge Collection, Hudson River Maritime Museum. Patterning itself after the Northwestern, a group of eastern ice yachting enthusiasts met in 1937 at the Larchmont (N.Y.) Yacht Club to form the Eastern Ice Yachting Association. There are, however, a few differences in classification. The eastern body calls the up-to-250 square-foot group Class X, instead of Class B, and the newer organization lists an up-to-200 square-foot sail area as Class B, a type not recognized by the Northwestern. In addition to the standard classifications, the Scooter and the D.N. 60 (Detroit News, 60 square feet of canvas) attract considerable attention. The Scooter, a remarkable amphibian which sails serenely on ice or in water, is the pride and joy of the South Bay Scooter Club, a member of the Eastern Association. It is believed that Coast Guardsmen, tired of long winter walks across ice for supplies, developed the first Scooter. They put runners on the bottom of one of their flat-bottomed sailboats and it worked. The boat has no rudder for water sailing and no movable runner for steering on ice. Direction is controlled only by shifting weight and sail handling. The D.N. 60 sprang from that Detroit newspaper's hobby shop, as an economical boys' sailing craft. It has turned out to be another case of the parents playing with their kids' electric trains. Adults love them. Their surprising speed and easy construction resulted in the building of almost 100 in the Detroit area alone. And the News now sponsors annual competitions on Lake St. Clair for their popular “baby.” The skeleton of an ice yacht is T-shaped, with the fuselage forming the long part, and a cross-piece or "runner plank" the horizontal. There are three runners or skates. The ones at each end of the runner plank are fixed. The steering runner, at the end of the fuselage, is moveable. Originally, all yachts were stern steerers. The runner plank was forward, the steering skate in the rear, behind the yachtsman's seat. Stern steerers have one pleasant advantage: boats using this design do not capsize easily. But the winter sailors wanted speed, and in the 1920's the Meyer brothers of Wisconsin began experimenting with bow-steering. Boats with bow-steering have the runner plank crossing the rear seat. The steering runner is at the front end of the fuselage. The bow steerer is faster - much faster. And sufficient pressure is kept on the steering runner to afford traction and maneuverability. But to counteract these advantages, the bow steerer spills more readily. Championship regattas of both the Northwestern and Eastern Associations are run in three-heat series to determine the champion of each class. The Northwestern winds up with a Free-for-All in which all classes are eligible. The Eastern concludes with an Open Championship limited to class titlists. With the present pre-eminence of the Skeeter, the International Skeeter Association Championship Regatta now is widely regarded as the "World Series" of the sport. The I.S.A. runs a five-heat series, weather permitting. The international character of the organization stems from the fact that it has member clubs in both the United States and Canada. Winners are determined on a point basis. Ice yachting's man of the year for 1947 probably was Jim Kimberly of Chicago, formerly of Neenah, Wis. Kimberly, who took his first ice boat ride at the age of five, won last year's International Skeeter Association title and the Northwestern Free-for-All. The 40-year-old executive is seeking additional titles this season in his 22-foot Skeeter, “Flying Phantom III”, one of several boats he owns. In racing, all boats are staggered at the starting line to give each entry unbroken wind. Lots are drawn for post positions and the order is reversed in successive heats. Races begin from a standing position, and here the yachtsman discovers the importance of a good pair of legs. At the crack of the gun he must take off like a sprinter for 25 to 50 feet, pushing his yacht to get "way" on her. Once underway, he needs all his skill to keep the boat moving. Inept handling stops the boat and the runners take a freezing grip on the ice. Then, out steps the yachtsman to give another starting push. This, of course, means a tremendous loss of face for the winter sailor. The sport is dangerous and thrilling. The most exciting moments come at the turning markers around which racers try to cut as sharply as possible. When one yacht overtakes another at this point, the leader is required to leave "stake room" (sufficient space) for the overtaking yacht to pass between him and the marker. Sometimes the cry is not heard, or a racer figures he has left sufficient room. Then the spectator sees two strong-willed ice yachtsmen tacking toward the stake at 90 miles an hour on sheer ice with no brakes to soften any possible collision. To make matters worse from the yachtsmen's point of view, the slightest touch of craft to marker means automatic disqualification from the race. Even pleasure cruising has its hazards. Good natural ice surfaces of sufficient size are rare. And these are subject to pressure ridges, weak ice and stretches of open water caused by currents and thaws. A quick plunge into icy water in the middle of winter with the nearest helping hand miles distant, is a sobering consideration for any frost-bitten sailor. The Detroit Ice Yachting Club has fostered one of the more exclusive organizations in the world - the Hell Divers. To be eligible, a yachtsman merely has to take the plunge and survive to tell the story. While the Skeeter pilots crow about their superiority over the larger boats, they frankly admit that the speed record probably will remain in the hands of Class A men. Speed runs are made over a straight measured course, under ideal wind and ice conditions and from a flying start. It is under the varying conditions of ice and wind in competitive racing - where maneuverability is at a premium - that the big boats are left behind. THE END Editor's Note: A future History Blog will discuss the Hell Divers. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

0 Comments

Editor's Note: The following essay is by author and steamboat scholar Richard V. Elliott (1934-2014). His two volume history of Hudson River Steamboats "The Boats of Summer" is coming soon from Schiffer Publishing. More information about hospital ships can be found here. While "Dean Richmond" was being torn apart at Boston in 1909, the City of Yonkers ventured to consider purchasing the old steamer for possible conversion into a floating hospital. At the time, certain officials wanted a craft for use in providing quarantined care of convalescing children and contagiously diseased patients. Yonkers' Mayor Warren wrote to Alexander M. Wilson of the Boston Association for the Relief and Control of Tuberculosis, asking his advice about purchasing the "Richmond" for hospital duties. An Equity of $3,000 and a Sad State Mr. Wilson went to the yards of Thomas Butler in Boston, where the once well respected steamer was being dismantled, took a good look at her and sent his appraisal to May Warren. In a rather ambivalent manner, Wilson reported: "I have just returned from an inspection of the "Dean Richmond", and I must confess that I feel incompetent to render a judgement as to its value to you. It is difficult to determine just what you are to secure for $4,000 …. As the boat stands, it is in a sad state of disorder … would cost another $1,000 to tow her to New York …" Wilson was particularly impressed with the "Richmond's" hull, reporting that the copper plating of the hull was worth $3,000 alone, and exclaimed, "there is an equity of $3,000 in the boat if you take the bare hull." He then went on to say, "The hull, however, is apparently in good condition, it has not needed to be pumped out since July 2 … and if you are limited to a floating hospital, I should think that you could not secure so much room for so little money in any other hulk that you might find." His report came to Yonkers July 26. Yonkers Declines Offer The 'high cost' of acquiring the remains of the steamer, even though she hadn't leaked appreciably for 24 days, was the reason expressed by the City Mayor in declining the opportunity to purchase the "Dean Richmond's" hull. After reading Wilson's report, Mayor Warren stated, "…it would now seem that that (this floating hospital) was impracticable, because the cost to the city would be too great, and the same amount of money could be used to better advantage in the establishment of a land camp." Thus, with this last hope for further service dashed, the scrappers continued their job of dismantling. So ended the life of "Dean Richmond." If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

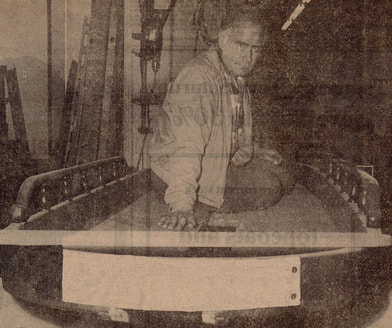

Editor's Note: This post is prepared from newspaper articles from The New York Times, Sunday, January 28, 1973, By Woody N. Klose; Hudson Register Star, February 17, 1976 and Soundings December 1972 by Elizabeth Manuele. The language, spelling and grammar of the article reflects the time period when it was written. For information about current ice boating on the Hudson River go to White Wings and Black Ice here. The New York Times, Sunday, January 28, 1973, By Woody N. Klose It is because of Franklin Delano Roosevelt's abiding love for the river and its winter ice that a slice of Hudson Valley history could be reconstructed last year in an 80‐foot‐long basement in a house high on a bill overlooking Newburgh. There, in the house of contractor, Robert R. Lawrence, a band of devoted valley men reconstructed the legendary gaff‐rigged ice yacht "Jack Frost". Had it not been for Roosevelt, the "Jack Frost" would long ago have become just another part of the rich valley earth. Commodore Archibald Rogers of Hyde Park owned the original Jack Frost, an iceboat of staggering dimensions. Built in 1883, the original "Jack Frost" carried 760 square feet of sail and measured 49½ feet from bow to stern along the backbone. In 1938 when the boathouse in which the "Jack Frost" was stored was destroyed by a hurricane, Roosevelt, concerned about the future of iceboating, gave the huge boat to Richard Aldrich of Barrytown. Aldrich had done much to keep alive the spirit of iceboating and, in the process, had amassed a sizable collection of antique ice yachts of Hudson River design, with the steering runner in the stern. Unfortunately, the original backbone, cockpit and runnerplank of the "Jack Frost" had been left in the open, near the remains of the boathouse, where they disintegrated and disappeared. But the hollow spars and much of the hardware were saved, and using dimensions on file in the archives of the Roosevelt Library, the "Jack Frost" was born again. Under the supervision of Ray Ruge, a foremost ice yacht expert, and Lawrence, the "Jack. Frost" was reconstructed, incorporating the pieces of the original boat. However, the craftsmen did not reconstruct the original "Jack Frost", designed and built in 1883 but refashioned the one of 1900, a slightly different model. As was the custom then, during all the modifications she never lost her name. While the owner might have a new backbone constructed or alter the size of sails or runners, he would not change the name of his prize boat. So the name, "Jack Frost", was transferred from boat to boat over two decades and down through half a century as the ice‐yacht was created, modified, almost destroyed and eventually reconstructed.  Cockpit Box - Commodore Robert Lawrence of the Hudson River Ice Yacht Club tries out the partially restored cockpit box of the "Jack Frost". The box is made of Honduras mahogany, oak, whitewood and trimmed with brass. A crew will man this cockpit when the famous 19th century iceboat, the “Jack Frost” is completed. Photo by Robert Richards from the Ray Ruge archives. Hudson River Maritime Museum. It was a problem, locating and buying timbers large enough to reconstruct her. The Hudson River Ice Yacht Club procured 10 pieces of Sitka spruce from the West Coast. Sitka spruce grows only in Alaska and British Columbia and is especially prized for its uniform character and long, straight grain. The club paid $1,000 for this valuable wood. The racing history of the "Jack Frost" is as unusual as the craft itself. Sailing for the Poughkeepsie Ice Yacht Club in 1883, her maiden year, she won the Ice Yacht Challenge Pennant of America, beating sailors and boats from North Shrewsbury, N.J. She won again in 1887, under the colors of the Hudson River Ice Yacht Club. In 1893, she took on the Orange Lake Ice Yacht Club for the pennant, and the result was the same. There were two races for the pennant in 1902 and "Jack Frost" sailed home with the trophy both times. Since then, the race for the challenge pennant and even the "Jack Frost" have almost become forgotten. They began to be “things that can wait till next year.” By World War I, ice yachting on the Hudson had all but vanished. Thanks to the leadership of Ruge, Lawrence, Aldrich's son, Ricky, and many others, iceboating on the Hudson River is coming back strong. Hudson Register Star, January 17, 1976 Historic Ice Yacht Glides Down Hudson River Again “Jack Frost”, four-time winner of the ice yacht Challenge Pennant … was taken off the ice for many years. It was launched on Orange Lake in 1973 after the Hudson River Ice Sailing Club spent three years restoring it. In was put back on the Hudson (River) in January 1976 off Croton. In February it was trucked to Barrytown when the ice off Croton began to break up. It needs at least six inches of ice to support its 2,500 pound weight. Robert Bard of Red Hook, a Hudson River Ice Sailing Club member, said the restoration was completed by the combined effort of many persons who often met Tuesday evening after work to lavish attention on the boat. Reid Bielenberg of Red Hook assisted with the rigging, and Bard helped mix adhesive. Other local men who helped in different stages were Dick Suggat of Rhinebeck, Earl A’Brial of Red Hook, Bob Fennel of Barrytown and Rick Aldrich of Barrytown. Bard said the craft was launched at Barrytown with some difficulty, because of its weight and size. Its mast is more than 30 feet tall and seven inches in diameter. The boom is 33 feet long, and its main runners are 28 feet long. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's Note: The following text is a verbatim transcription of an article written by George W. Murdock, for the Kingston (NY) Daily Freeman newspaper in the 1930s. Murdock, a veteran marine engineer, wrote a regular column. Articles transcribed by HRMM volunteer Adam Kaplan. For more of Murdock's articles, see the "Steamboat Biographies" category. The “Empire of Troy” was constructed in 1843, being 307 feet long, and was one of the leading Hudson river boats of her time, running in line with the steamboat “Troy” on the New York-Troy route. She was the second large steamboat built for the Troy Line and was supposed to be called the “Empire” but her owners feared that she might be mistaken for an Albany boat so they had the name “Empire Of Troy” painted in large, black letters on her paddle-wheel boxes. These owners had plenty of reason to be proud of their vessel because she was the largest of her type that had been built up to that time. However, despite her size and construction, she turned out to be a rather unfortunate craft, meeting with many mishaps. In April of 1845, she met with a most peculiar accident. During a dense fog she ran into the pier at the foot of 19th street in the North River. Although this pier was constructed of solid, ballasted crib-work, the impact was so great the steamer’s hull cut through the pier for a distance of 30 feet, doing little or no damage to the vessel but completely wrecking the pier. On the night of May 18, 1849, the “Empire of Troy” left New York bound for Troy. While proceeding up Newburgh Bay at 10 o’clock at night, she was in a collision with the sloop “Noah Brown”. The “Empire of Troy” began to settle immediately and the steamer “Rip Van Winkle” which was following the ill-fated vessel, succeeded in rescuing a great number of passengers, but even at that some 24 lives were lost. The “Rip Van Winkle” towed the “Empire of Troy” over to the flats on the eastern side of the river where she settled on the bottom. She was later raised and repaired, and continued to run on the Troy route until another accident of a similar nature eventually put her out of service. This second accident which wrote “finis” to the steamer’s career happened between two and three o’clock in the morning of July 16, 1853, of New Hamburgh. The pilot of the “Empire of Troy” saw the sloop “General Livingston” trying to beat across his bow. He threw over his wheel so as to give the sloop leeway, but the “General Livingston suddenly sheered off and struck the “Empire of Troy” on the larboard side, throwing her boiler from its anchorings and staving in the guards and paddlebox. The passengers, alarmed by the terrific crash and the noise of escaping steam, rushed from their berths and staterooms into the upper cabin and saloon, only to be submerged in the cabin and scalded in the saloon. A chambermaid, frightfully scalded, jumped overboard and was drowned. Captain Smith ordered the bell rung to call help but before any aid arrived, the vessel had careened to the leeward and was rapidly filling. The sloop “First Effort” and the propellor-driven “Wyoming” then came alongside and took off the passengers, and later the “Wyoming” pushed the “Empire of Troy” into the shallows on the eastern shore where she sank in eight feet of water. The accident caused the death of eight people and injured 14 others. Those that were scalded were given first aid at the residence of Mr. Van Renssaleer at New Hamburgh. The “Empire of Troy” was finally raised but it was found that her hull was badly damaged and so she was dismantled after a record of only 10 years service. AuthorGeorge W. Murdock, (b. 1853-d. 1940) was a veteran marine engineer who served on the steamboats "Utica", "Sunnyside", "City of Troy", and "Mary Powell". He also helped dismantle engines in scrapped steamboats in the winter months and later in his career worked as an engineer at the brickyards in Port Ewen. In 1883 he moved to Brooklyn, NY and operated several private yachts. He ended his career working in power houses in the outer boroughs of New York City. His mother Catherine Murdock was the keeper of the Rondout Lighthouse for 50 years. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor’s Note: The following text is a verbatim transcription of an article featuring stories by Captain William O. Benson (1911-1986). Beginning in 1971, Benson, a retired tugboat captain, reminisced about his 40 years on the Hudson River in a regular column for the Kingston (NY) Freeman’s Sunday Tempo magazine. Captain Benson's articles were compiled and transcribed by HRMM volunteer Carl Mayer. This article was originally published January 23, 1977. Tugboats in some respects are like people. Some have long lives, some short ones. Some during the course of their lifetime change greatly in appearance. And some seem to be more accident prone than others. All tugboats, especially in the old days, had their share of mishaps, which were caused by any number of things. River traffic was greater then, and there were fewer buoys, beacons and other navigational aids. It was a time of no radar, which today permits the pilot to “see” where he is in the fog, blinding snow or rain storm. In addition, of course, there were and are always those mishaps caused by human error or folly. The debacles that befell the tugboat “Hercules” of the old Cornell Steamboat Company are perhaps typical. Some of the incidents were not without a touch of humor. Others have a bit of pathos. The “Hercules” — a good name for a tug — was a member of the Cornell fleet during its heyday. She was built in 1876 and remained in active service until 1931. "Herk," as they often called her, was smaller than the large tugboats that used to pull the big flotillas of barges, but also larger that the helper tugs that regularly assisted every big tow. As a result, she was used for a lot of special tasks: towing dredges, expressing special barges or lighters, pulling steamboats from winter lay up to a shipyard, etc. "Herk" also had a reputation as an ice breaker and was used often for this purpose - particularly in the spring. To help her in the ice, she had extra stout oak planking and steel straps all around her bow. One day in the summer of 1917, the "Hercules" was running light to Rondout. Her pilot was off watch, asleep in his bunk, and the captain was dog tired. Since it was a clear summer’s day, the captain decided to grab a nap and let the deckhand steer. After he went below for his nap, a heavy thunder shower came up off Esopus Meadows lighthouse. The decky altered course, and — thinking he was on the proper heading — kept her hooked up. A few minutes later, "Herk" came to a slow stop and raised partly out of the water. When she listed, the captain woke up and ran to the pilot house. But the heavy rain was coming down in sheets. He couldn’t see a thing. All he knew for sure was that his tug was aground and the tide was falling. When the rain stopped a few hours later, the problem was obvious. The deckhand had turned too much towards the northwest, going aground directly off the old Schleede’s brickyard at Ulster Park. The “Hercules” had plowed right over the Esopus Meadows, coming to rest with her bow on the north bank and her stern on the south bank, straddling the cut channel between the Meadows and the brickyard. The tide was ebbing and, unsupported as she was in the middle, her crew was afraid the Herk would either break her back or roll over on her side. But as the water fell, she listed only a trifle and sat there— just as she had run aground. “Herk" must have been made of good stuff to stand that ordeal. The next high tide, Cornell sent down the tugs “Harry", “G. C. Adams” and “Wm. S. Earl” and pulled her off, none the worse for the experience. The deckhand who put her there lived in Port Ewen. For years afterward, he took a lot of ribbing for trying to put his tug up in his own backyard. Two years later — in 1919 — the “Hercules" had another mishap. For this one, her pilot was fired. At that time, "Herk" was expressing a coal boat from New York to Cornwall. She was off Jones Point at about 1:30 in the morning, when the pilot, who used to so some fishing, said to the deckhand, “Steer her a little while. I’m going down to the galley and knit on my fish nets.” While the pilot knitted, the decky dozed off at the wheel, and the “Hercules” hit a rock near Fort Montgomery. It put a sizable hole in her hull, she sank in 45 feet of water. The salvage company later located her by her hawser, which was still attached to the coal boat, and floated her like a big buoy. “Herk” was raised and repaired, and she ran for another 12 years. After the accident, the president of the Cornell Steamboat Company is said to have called the pilot into his office to ask him how it happened. The pilot was truthful, telling him where he was and what he'd been doing, whereupon Cornell’s president is supposed to have said: “Well,”(calling the pilot by name),"now you can go home for the rest of your life and knit nets to your heart’s content." And he never worked on a Cornell tugboat again. In 1924, the “Hercules" had another near accident— but this one ended on a happier note. The tug was running light in the upper river on her way to Albany. It was the era before three crews manned each boat, and the captain was off for the weekend. Peter Tucker, the pilot, was in charge and standing a double watch. At the time, it was early morning and breakfast was ready. The cook claimed he had a Hudson River pilot’s license and came up to the pilot house saying, "Now Pete, go down and enjoy your bacon and eggs. I'll steer for you.” Pete said, “‘Are you sure you know the channel?", to which the cook replied, "Yes, yes I know all about it." So pilot Tucker went down to the galley to have his oatmeal, bacon and eggs. At that point, "Herk” was off the Stuyvesant upper lighthouse. A little while later, she was at the junction of the Hudson and Schodack Creek. Given a choice, the poor cook thought he was to go up the shallow Schodack, instead of west and up the Hudson. Ned Bishop, the chief engineer, came out of the galley just in time to see where they were heading. Yelling to pilot Tucker, he said, “Pete, where is this guy going?" The pilot looked out of the galley, and there they were, headed up Schodack Creek. Pete started to run up the forward stairway to the pilot house, hollering to Ned Bishop as he ran, "Full speed astern!" The chief reversed the throttle just in time. The "Hercules" slid up on the bank and right off again. If he hadn’t been so quick, "Herk" would probably be there yet. Going into the pilot house, Pete said to the cook, “I thought you knew the river." The cook (rather sheepishly) replied, "Well, that’s the way I always went.” The pilot retorted, "What’s the use? Go down and start dinner. Now!” And so ended another incident of the many in the long life of the "Hercules." AuthorCaptain William Odell Benson was a life-long resident of Sleightsburgh, N.Y., where he was born on March 17, 1911, the son of the late Albert and Ida Olson Benson. He served as captain of Callanan Company tugs including Peter Callanan, and Callanan No. 1 and was an early member of the Hudson River Maritime Museum. He retained, and shared, lifelong memories of incidents and anecdotes along the Hudson River. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

|

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 [email protected] Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |