History Blog

|

|

|

|

|

Happy New Year! And what a year it has been. To ring in 2022, we thought we'd celebrate with an old tradition involving Hudson River steamboats.

For years, Pratt Institute in New York City celebrated New Year's Eve by taking a collection of steam whistles, including many from historic Hudson River steamboats, hooking them up to the steam plant that heats the campus, and blowing them all at midnight. Check out the cacophony in the video below, from the 2012 celebration.

The whistles were from the collection of steam engineer and steam historian Conrad Milster, who worked for decades as the steam plant engineer for Pratt. Unfortunately, the celebrations came to a halt in 2015, but Milster continues to work in Pratt's steam plant, which is one of the oldest in the world.

Milster worked in the engine rooms of Hudson River Day Line boats as a young man, and has worked continuously at Pratt since 1958, although in recent years there have been efforts (unsuccessful) to force him into retirement. To learn more about Conrad Milster, his work at Pratt, and his extensive collections, check out the short documentary below (2019, Long Island Traditions).

To learn more about Milster's drive to collect recorded sounds, including Hudson River steamboat whistle and engine sounds, check out this audio interview with Sound & Story:

And whether you're ringing in the new year with the Times Square ball drop, attending a party, or going to bed early, play a steam whistle for us and we'll see you in 2022!

If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

0 Comments

Editor's Note: The following is a verbatim transcription of a chapter from Spalding's Winter Sports by James A. Cruikshank, published in 1917 and part of the Ray Ruge Collection at the Hudson River Maritime Museum. Many thanks to volunteer Adam Kaplan for transcribing this booklet. The modern skate, briefly described, is of two kinds and several patterns. One is intended for speed skating and the other for figure skating. The best pattern for speed skating consists of a very thin, extremely hard, flat, steel blade, tapered from one-sixteenth of an inch at toe to one thirty-second of an inch at heel, fourteen and one-half and fifteen and one-half inches in length, set in a hollow steel tube, from which hollow steel supports or uprights run to the metal foot-plates, which are in turn riveted to a thin, close fitting shoe having no heel. Some of the fastest speed skaters still use the old fashioned wood top skate screwed to the heel of the shoe when the ice is reached and fastened over the toes with straps; but this pattern is rapidly going out of vogue. The hockey skate, used in that game and now of great popularity among skaters of all ages and classes and sexes, whether they play hockey or not, consists of a flat blade, with either three or four uprights or stanchions running to the metal foot-plate screwed or riveted to the shoe. The length of the blade depends upon the length of the skater’s foot. This skate is generally very slightly curved where the blade rests upon the ice, making quick turns and sharp curves possible. It is an excellent skate with which to learn the art of skating, but after the beginner has learned to feel fairly safe should be changed for the rocker skate or figure skate, if further progress in the sport of Figure Skating is an object. It is unfortunate that so many young people take up the flat-blade skate, either of the hockey or racing pattern, and then persistently stick to that pattern, since no general advancement in the achievement of curves and patterns is ever possible to the user of the flat-blade skate. Undoubtedly the best pattern for the figure skate is that which was taken to Europe by Jackson Haines, the American skater, in 1865, and adopted by almost every European skater of fame from that day to this. With the revival of skating in the United States, and especially the Continental or “fancy” style, has come a demand for a skate best suited to the graceful figures that render this form of the art so attractive. This old, yet new, skate has but two uprights or stanchions from the blade to the foot or heel plates, the blade curves over in front so as almost to touch the shoe; there is considerably greater distance from the skater’s heel to the ice than in former patterns, and larger radius of the curve of the blade where it rests upon the ice. The blade is splayed, or wider in the middle than at the toe and heel, and there are deep knife edge corrugations at the toe for pirouettes and toe movements. This is the skate which is now being used by the best skaters of the world, and the only pattern on which the larger, freer, bird-like movements so characteristic of the best skaters of Europe, are possible. It is an interesting fact that this skate is now the recognized standard of the leading instructors and experts in Figure Skating in all the prominent rinks and in theatrical attractions in which ice spectacles are a feature. Skating, whether the beginner has in mind speed or figure work, is best learned without human aid. An old, strong chair, to the legs of which have been fastened wooden runners, is the best of all devices for starting the young skater on the right balance and contributing to his self reliance and confidence. Very early in the attempts at the sport, the beginner will decide whether he is interested in Speed or Figure Skating, and he is then urged to select the correct outfit rather than adopt habits which it will be difficult later to break. There are scores of skaters now using the flat blade hockey or racing skate who will never achieve satisfactory speed, but who are peculiarly adapted to success in Figure Skating. Speed Skating is interesting for a time, and hockey is a splendid athletic game, but the figure skater has a pastime and an athletic pursuit which will interest him for a lifetime, and in which there are intricacies as fascinating as a geometrical puzzle. There are excellent books on the new forms of Figure Skating now available, the latest of which, Mr. Irving Brokaw’s “Art of Skating” and “Figure Skating for Women,” published in the Spalding Athletic Library, should be in the hands of every lover of the sport. After the beginner has attained some measure of confidence, the skate sail will be found a most interesting diversion and addition to the sport. There are many patterns of skate sails. The simplest, as well as one of the best is the rectangular pattern, fashioned of two uprights at the fore and aft ends of the sail with a cross piece as spreader. The size of this sail will depend on the designer and the sport he seeks. The average size recommended for an expert skater would be 6 to 7 feet in height and 10 to 12 feet in width. The wooden spars at the bends should be of pine or spruce, squared, thicker in the middle than at the ends, and of one piece. The center spreader may be jointed or hinged. The best material for the sail is either unbleached muslin, which is very cheap, or the best sea island cotton, known as “balloon silk.” In the sail can be set an oval or circle of celluloid as a window through which the skate sailor may watch his course. The skate sail described can be made by almost any amateur, will cost less than five dollars, and will return more sport for its cost than almost any other winter sport implement. There are many other patterns of skate sails, the next best being the triangular or pyramid shape with the base of the pyramid parallel with the skater and the long end of the sail stretching out behind. The right dimensions for such a sail for the average person will be about 9 feet for the upright spar and 10 to 12 feet for the boom. The spars can be made of heavy bamboo, and by means of a small pulley over the forward end of the boom the sail can be stretched taut. There is another foreign pattern sail which has a boom stretching across the two end spars and projecting beyond them a foot or so. Such a model requires a larger field of ice than those which have been described. Uninformed advisers recommend the flat blade skate for Skate Sailing. They are wrong, because sharp turns and curves have to be made for successful Skate Sailing. The best skate for the sport is either the regulation figure skate or a hockey skate having a curved blade. The skate sail ought to be used only where there is ample freedom; it is not adapted to small skating ponds or rinks since high speed is frequently developed, even up to thirty miles an hour, and dangerous accidents may occur. Anyone can learn the use of the skate sail with a few hours’ practice. Unlike the ice boat, which it so much resembles, tacking is done exactly the same as with a small boat, with the exception that when the sailor is ready to “come about” he simply throws the sail up over his head, makes his right angle turn into the new course and the sail comes down in correct position. It is also possible to shift the sail forward while under full speed until it is past the center, then slip it from one side of the body to the other, make the turn into the new course, and continue on the new tack. Magnificent competitive sport can be had with the skate sail by organizing “one design classes,” just as in small boat sailing, so that every sailor has similar equipment and there are no odds. Differences in weight of the contestants will be about equalized by the advantage of weight in one position of sailing as against its disadvantages in another. Women pick up the sport readily and find it most interesting. Many a woman has learned from the skate sail, for the first time, that she really can handle a sail so that she is able to get back to the place from which she started by the otherwise incomprehensible route known in yachting as “tacking.” Warm gloves, tight fitting clothing, and some sort of face protection are advisable for this sport. AuthorJames A. Cruikshank was an expert on outdoors sports during the first half of the 20th century. Born in Scotland but spending most of his life in New York, he was the editor of The American Angler magazine, Field and Stream, and wrote numerous articles for a wide variety of other magazines and newspapers throughout his career, including the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. He also published at least three books: Spalding’s Winter Sports (1913, 1917), Canoeing and Camping (1915), and Figure Skating for Women (1921, 1922). He also contributed a chapter on artificial lures to The Basses: Freshwater and Marine (1905). In addition to his writing, Cruikshank was involved in public speaking, doing talks on outdoor sports sometimes illustrated by motion pictures. An avid photographer, Cruikshank’s photos often featured in his illustrated lectures, his articles, and his books, as he encouraged readers to take their own cameras out-of-doors. He had a home in the Catskills as well as a home and offices in New York City, and in the 1930s he helped found the Hudson River Yachting Association. At one point, he managed the Rockefeller Center ice skating rink, and another in Rye, NY. His wife Alice was also an avid camper and hiker, and they often traveled together. In 1909, Alice went “viral” in newspapers around the country by being the first person to blaze a trail between Mount Field and Mount Wiley in the White Mountains of New Hampshire (James brought up the rear). James and Alice eventually moved to Drexel, PA and were vacationing in Lake Placid in July of 1957 when James died unexpectedly at the age of 88. What do you think of James A. Cruikshank's encouraging women to take up ice skating? Did you ice skate as a kid? Do you still?

Stay tuned next week for our next chapter. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Today's Media Monday is a great story about being stranded on the Newburgh Beacon Ferry! When the weather gets colder, most boat traffic on the Hudson River ceases, except for commercial traffic in the shipping channel, which today is kept open by Coast Guard icebreakers.

Most historic boat traffic on the Hudson River was seasonal, too, mostly because the Coast Guard icebreakers are a 20th century invention. Because they traveled the same space frequently, most ferries tried to stay in service as long as possible in the days before bridges, and they were often the last vessels on the river each year. But it didn't always work out so well! Listen below for the full tale.

Brief summary: In the early 1950's, the Ferry got stuck in the ice on its 11:30 PM return trip to Beacon. Betty Carey remembers the story of one passenger who was stranded on the boat until rescued the next morning.

Have you ever gotten stranded because of snow or ice?

If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's Note: The following is a verbatim transcription of a chapter from Spalding's Winter Sports by James A. Cruikshank, published in 1917 and part of the Ray Ruge Collection at the Hudson River Maritime Museum. Many thanks to volunteer Adam Kaplan for transcribing this booklet. Pry yourself away from that steam radiator some snowy day and take a winter walk! Put behind you the mellow charm of the open fire; it will be even more delightful when you return. Hunt up a few old togs, woolen underwear, close woven woolen suit, heavy sweater, mittens, cap with ear tabs, and heavy waterproof shoes and sally forth on the quest for a new sensation. Never mind that overcoat; you will never miss it after that first half mile. And don’t forget to stuff a few crackers in your pocket for that utterly unexpected hunger which will be waiting your arrival somewhere along the road. Now, strike out! Immediately after warming up with the vigorous exercise, you feel perfectly sure that there is some sort of curious exhilaration which the air of summer never furnishes. Your imagination is not fooling you. There is one-seventh more oxygen in cold winter air than in warm summer air. That is the reason the “fire burns brighter.” And by the same token every human faculty is keener and sharper. Incidentally the falling snow carries to earth with it all floating impurities and you breathe the purest air to be found at any time of the year. You have made but a few rods when you discover that snow is the greatest artist of nature. That unsightly shack which so distressed you, has taken on forms of unknown beauty; even that ash heap, eyesore that it was, now furnishes curves of unsullied purity; the snow, like a mantle of charity, has transformed the ugly into the beautiful. Nor is its gift to the world merely pictorial. It is nature’s warm blanket. This cold, frozen thing saves the wheat and the grain from freezing; fills up the chinks between ground and farmhouse, window and frame and makes the home warmer than it was before. Close to your home, no matter where you live, the records on the snow will be found interesting and fascinating. The average city park is full of their strange story. To the open mind of the nature-lover they start all sorts of interesting speculations. Mouse, sparrow, squirrel, rabbit, fox, dog- which are they and what story do they tell? You may even find pathetic tragedies writ clear in the snow, if only you have learned to read the winter book of nature. Here see the wide sweeping record of the wings of an owl as they touched the snow on either side of the tiny tracks of a mouse. Then the prints of the wings become deeper and clearer, and here, where a little tuft of bloody fur is found, and the snow is beaten down all about, the trail suddenly ends. Perhaps the story of the fox that dined upon squirrel or partridge is spread out there full upon the ermine page of nature. Here, indeed, is a new chapter in your reading of nature’s secrets; it is stranger than any fiction and dramatic as a novel. Then sunset across the fields of white, nowhere more exquisitely beautiful. Great bloody stabs of crimson athwart the western sky. The very “souls of the trees,” as Holmes called them, when freed of their summer bodies. Across the tiny brook hurrying to sea under its arching canopy of snow-laden willow and alder. Then the open fire! No blaze so bright, no cheer so real as that which greets a winter rover fresh from a brave little ramble over the fresh snow. Take a winter walk! AuthorJames A. Cruikshank was an expert on outdoors sports during the first half of the 20th century. Born in Scotland but spending most of his life in New York, he was the editor of The American Angler magazine, Field and Stream, and wrote numerous articles for a wide variety of other magazines and newspapers throughout his career, including the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. He also published at least three books: Spalding’s Winter Sports (1913, 1917), Canoeing and Camping (1915), and Figure Skating for Women (1921, 1922). He also contributed a chapter on artificial lures to The Basses: Freshwater and Marine (1905). In addition to his writing, Cruikshank was involved in public speaking, doing talks on outdoor sports sometimes illustrated by motion pictures. An avid photographer, Cruikshank’s photos often featured in his illustrated lectures, his articles, and his books, as he encouraged readers to take their own cameras out-of-doors. He had a home in the Catskills as well as a home and offices in New York City, and in the 1930s he helped found the Hudson River Yachting Association. At one point, he managed the Rockefeller Center ice skating rink, and another in Rye, NY. His wife Alice was also an avid camper and hiker, and they often traveled together. In 1909, Alice went “viral” in newspapers around the country by being the first person to blaze a trail between Mount Field and Mount Wiley in the White Mountains of New Hampshire (James brought up the rear). James and Alice eventually moved to Drexel, PA and were vacationing in Lake Placid in July of 1957 when James died unexpectedly at the age of 88. Stay tuned next week for the next chapter of Spalding's Winter Sports.

If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today! Editor’s Note: The following text is a verbatim transcription of an article featuring stories by Captain William O. Benson (1911-1986). Beginning in 1971, Benson, a retired tugboat captain, reminisced about his 40 years on the Hudson River in a regular column for the Kingston (NY) Freeman’s Sunday Tempo magazine. Captain Benson's articles were compiled and transcribed by HRMM volunteer Carl Mayer. See more of Captain Benson’s articles here. This article was originally published December 17, 1973. Last summer a rather ramshackle old building on Abeel Street, directly opposite the Fitch bluestone building so recently and magnificently restored by James Berardi, was demolished. It was known as the Santa Claus Hotel and, at the time, questions were asked as to where the building had gotten its odd name. As far as I can determine, the old hotel was named after the steamboat “Santa Claus.” Way back in the 1840's, the community of Kingston was located inland where the uptown area of the city is today. Access to the Hudson River on Rondout Creek was over three roads. The longest road went through a swamp to what later became Kingston Point. Another came down a steep hill to the small but bustling hamlet of Rondout. The third, shortest and least steep was the road to Wilbur. Starting in 1848, a steamboat with the rather improbable name of “Santa Claus” began operating as a day steamer between Wilbur and New York. Since the steamer left Wilbur early in the morning, I have heard some enterprising individual shortly afterward built a hotel opposite the steamboat landing to provide accommodations for the travellers [sic] coming from inland to board the steamboat. Because ground transportation was primitive at best, many travellers would arrive the night before and stay at the hotel before embarking on their down river journey. Whether the fancy of the hotel's owner was caught by the steamer's name, or if the name was chosen solely to promote business is hard to say. In any event, it is my understanding the hotel was named for the steamboat. St. Nick Paintings The steamboat “Santa Claus” had been built in the early 1840's and first ran as a day steamer between New York and Albany. In 1847 the steamboat was used in a service between Piermont and New York, and then briefly returned to her old Albany run before starting her service from Wilbur in 1848. An unusual decorative feature of the steamboat were paintings of St. Nick himself going down a brick chimney with a bag full of all kinds of toys of the era which appeared on her paddle wheel boxes. During the early 1850's, the local landing of the “Santa Claus" was shifted from Wilbur to the fast growing and lusty village of Rondout. Operated by Thomas Cornell and commanded by David Abbey, Jr., she now ran as a night boat on opposite nights to the steamer “North America,” commanded by Jacob H. Tremper. The “Santa Claus" would leave Rondout for New York on Monday, Wednesday and Friday nights at 5 p.m. and return the following nights. During the latter part of the 1850 decade, Thomas Cornell withdrew the "Santa Claus” from the passenger trade, removed the passenger accommodations and converted the steamer to a towboat. During the winter of 1868-69, she was thoroughly rebuilt at South Brooklyn. When she came out in the spring of 1669, the name “Santa Claus" disappeared and on her name boards instead appeared the name “A. B. Valentine," in honor of the man who was the New York agent and pay master for the prospering Cornell Steamboat Company. Down River Tows As the "A. B. Valentine,” the sidewheel towboat was first used to pull the down river tow between Rondout and New York. But as some of the older boatmen told me their father had told them, she was not quite powerful enough for the large tows that were coming out of New York — sometimes with over a hundred canal boats and barges. Cornell then put more powerful side wheelers on the lower river and shifted the “A. B. Valentine" to towing between Rondout and Albany. On the upper river the “Valentine" ran opposite one of the best known towboats of them all, the old faithful sidewheeler “Norwich." I have been told their helper tugboats were the sister tugs “Coe F. Young” and “Thomas Dickson," the “Young” working mostly with the “Norwich” and the “Dickson" with the “A. B. [Valentine."] For many years a man lived in Sleightsburgh by the name of Fred Cogswell. He had been the pilot on the “A. B. Valentine" in her latter years. At the time the “Valentine” was withdrawn from service, Mr. Cogswell was a man well along in years and I am told S. D. Coykendall pensioned him off on a pension of $7 a month. He passed away in the early 1920's well into his nineties. At the turn of the century, the “A. B. Valentine" had outlived her usefulness and was layed up at Sleightsburgh at what later became known as the Sunflower dock. In the late fall of 1901 she was sold for scrapping. By a quirk of fate, on the day she was sold, the man for whom she was named, A. B. Valentine, died after serving as the New York superintendent of the Cornell Steamboat Company for half a century. The steamer left Rondout on Dec. 17, 1901 for Perth Amboy, N.J .where the steamboat built as the “Santa Claus” was finally broken up. Although there are a number of photographs of the steamboat as the "‘A. B. Valentine,” I know of no photos of her as the “Santa Claus,“ probably because during service under her original name photography was in its infancy. However, during the early 1930's there was a saloon on Abeel Street, just off Broadway, that had a lithograph of the "‘Santa Claus.” It was a broadside view with her Rondout to New York schedule imprinted on the sides. To my knowledge, this was the only likeness of the old steamer as the “Santa Claus." Now, this too, has long since disappeared. AuthorCaptain William Odell Benson was a life-long resident of Sleightsburgh, N.Y., where he was born on March 17, 1911, the son of the late Albert and Ida Olson Benson. He served as captain of Callanan Company tugs including Peter Callanan, and Callanan No. 1 and was an early member of the Hudson River Maritime Museum. He retained, and shared, lifelong memories of incidents and anecdotes along the Hudson River. If you'd like to learn more about the steamboat "Santa Claus," check out this extensive Wikipedia article.

If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today! Today's Media Monday post is another teaser trailer for our forthcoming documentary film, "Seven Sentinels: Lighthouses of the Hudson River." The museum is crowdfunding for this film on Indiegogo, so help us make it a reality and get some really cool perks in return. We have made significant progress toward our goal - will you help us reach it before January 13? "Ice Guardians" is a teaser trailer look at some of the amazing footage filmmaker Jeff Mertz got of the Hudson-Athens, Rondout, and Esopus Meadows Lighthouses last winter. As we approach the holiday season, it seemed apt to share the icy beauty with everyone. The drone footage also reveals how isolating life at a lighthouse in winter could be, and how the lighthouses themselves needed to be protected from the heavy floes of ice. If you missed the first trailer, catch up below! We have already received dozens of individual donations, as well as support from Ulster Savings Bank, Rondout Savings Bank, and Ulster County Cultural Services & Promotion Fund administered by Arts Mid-Hudson. But we've still got a ways to go before we reach our goal, and just under a month to do it in.

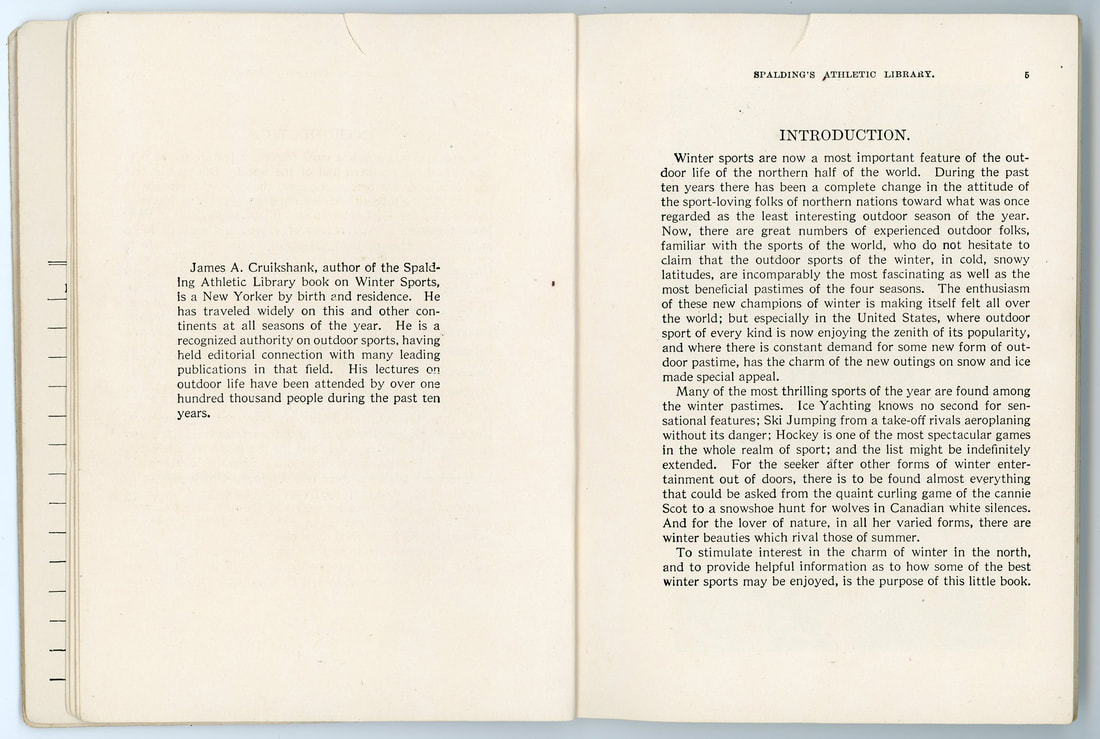

You can help by liking, commenting on, and sharing our social media posts, YouTube videos, and this blog post. If you'd like to do more to help, you can join our individual fundraiser contest, where you can get credit for donations from family and friends on Facebook and other platforms. Check out our latest campaign update to learn more. You can earn the same perks as higher level backers. And, if you'd like to donate to the film but don't want to do so online, you can always mail us a check! Send it to the Hudson River Maritime Museum, 50 Rondout Landing, Kingston, NY 12401 and write "Seven Sentinels" or "lighthouse film" in the check memo line. The Spalding Athletic Library and the American Sports Publishing Company were both founded by A.G. Spalding, owner of Spalding's Athletic Goods. Designed to produce affordable books on a wide variety of sports, rule books, and others, Spalding's conveniently included related catalogs and order forms for their goods in each inexpensive booklet. Published in 1917 and written by outdoor sports expert and author James A. Cruikshank, Spalding's Winter Sports is our featured artifact of the day, acquired by the Hudson River Maritime Museum as part of a collection of ice boating materials. And thanks to the transcription skills of volunteer Adam Kaplan, we'll be serializing each chapter of Winter Sports for the next several weeks. If you'd like to see the other sports booklets that Spalding offered (and there were hundreds), you can see some of their works digitized at the Library of Congress. The booklet features short articles on skating, skiing, snowshoeing, ice boating, tobogganing, hockey, and more. Be sure to join our mailing list to get updates and make sure you don't miss a chapter! The introduction starts below.  Interior pages of "Spalding's Winter Sports" by James A. Cruikshank, 1917. Ray Ruge Collection, Hudson River Maritime Museum. At left, the author's biography reads, "James A. Cruikshank, author of the Spalding Athletic Library book on Winter Sports, is a New Yorker by birth and residence. He has traveled widely on this and other continents at all seasons of the year. He is a recognized authority on outdoor sports, having held editorial connection with many leading publications in that field. His lectures on outdoor life have been attended by over one hundred thousand people during the past ten years." Winter sports are now a most important feature of the outdoor life of the northern half of the world. During the past ten years there has been a complete change in the attitude of the sport-loving folk of northern nations toward what was once regarded as the least interesting outdoor season of the year. Now, there are great numbers of experienced outdoor folks, familiar with the sports of the world, who do not hesitate to claim that the outdoor sports of the winter, in cold, snowy latitudes, are incomparably the most fascinating as well as the most beneficial pastimes of the four seasons. The enthusiasm of these new champions of winter is making itself felt all over the world; but especially in the United States, where outdoor sport of every kind is now enjoying the zenith of its popularity, and where there is constant demand for some new form of outdoor pastime, has the charm of the new outings on snow and ice made special appeal. Many of the most thrilling sports of the year are found among the winter pastimes. Ice Yachting knows no second for sensational features; Ski Jumping from a take-off rivals aeroplaning with its danger; Hockey is one of the most spectacular games in the whole realm of sport; and the list might be indefinitely extended. For the seeker after other forms of winter entertainment out of doors, there is to be found almost everything that could be asked from the quaint curling game of the cannie Scot to a snowshoe hunt for wolves in Canadian white silences. And for the lover of nature, in all her varied forms, there are winter beauties which rival those of summer. To stimulate interest in the charm of winter in the north, and to provide helpful information as to how some of the best winter sports may be enjoyed, is the purpose of this little book. Author James A. Cruikshank was a longtime New York resident and was an expert outdoorsman, writing and editing publications for American Angler magazine, Field and Stream, and more, as well as authoring books like Spalding's Winter Sports. He hiked, hunted, fished, boated, snowshoed, skied, ice skated, mountain climbed, camped, and more. He was also an avid photographer and gave public talks illustrated by his own photographs (which are also featured in "Spalding's Winter Sports") and even film reels. You can read a more extensive biography of him below. AuthorJames A. Cruikshank was an expert on outdoors sports during the first half of the 20th century. Born in Scotland but spending most of his life in New York, he was the editor of The American Angler magazine, Field and Stream, and wrote numerous articles for a wide variety of other magazines and newspapers throughout his career, including the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. He also published at least three books: Spalding’s Winter Sports (1913, 1917), Canoeing and Camping (1915), and Figure Skating for Women (1921, 1922). He also contributed a chapter on artificial lures to The Basses: Freshwater and Marine (1905). In addition to his writing, Cruikshank was involved in public speaking, doing talks on outdoor sports sometimes illustrated by motion pictures. An avid photographer, Cruikshank’s photos often featured in his illustrated lectures, his articles, and his books, as he encouraged readers to take their own cameras out-of-doors. He had a home in the Catskills as well as a home and offices in New York City, and in the 1930s he helped found the Hudson River Yachting Association. At one point, he managed the Rockefeller Center ice skating rink, and another in Rye, NY. His wife Alice was also an avid camper and hiker, and they often traveled together. In 1909, Alice went “viral” in newspapers around the country by being the first person to blaze a trail between Mount Field and Mount Wiley in the White Mountains of New Hampshire (James brought up the rear). James and Alice eventually moved to Drexel, PA and were vacationing in Lake Placid in July of 1957 when James died unexpectedly at the age of 88. Stay tuned next week for the next chapter in Spalding's Winter Sports (1917)!

If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today! In May of 2022, the Hudson River Maritime Museum will be running a Grain Race in cooperation with the Schooner Apollonia, The Northeast Grainshed Alliance, and the Center for Post Carbon Logistics. Anyone interested in the race can find out more here. Every game or race has rules: Not using the subway is a staple in Marathons, for example. The Northeastern Grain Race is no different, but, as with many games, if you pay close attention to the rules there's some clever ways to get ahead. The following ways to rules-lawyer yourself into a better score aren't exhaustive, but they might get you thinking. 1. You can use more than one vehicle. From farm to producer might entail using more than one vehicle, for example taking grain from the farm to a dockside by truck, then via ship to another dock, to be brought to its final destination by electric bike, as has been done by Schooner Apollonia in the past. This all counts as one voyage, from door to door, and fuel has to be logged for the entry to count from door to door. However, this also means that you could enter an entire cargo bicycle enthusiasts club as one voyage, and have them bring your cargo in a group ride. So long as it all happens at once and no one bike or biker makes more than one trip door to door, you'll qualify. This means you could also have the bike club do a couple loops as a segment of the cargo run, for example from a farm to a dock, and from the dock to the producer's door, provided it's different bike clubs on both ends. 2. You don't need to use the most direct route. The shipment must originate and terminate in the Northeast, but that's the only regional restriction included in the rules. You don't need to take the shortest route, and you don't need to be fast, as you have the entire month of May to complete the delivery if you want. While making a circumnavigation might be a bit absurd given the time constraint of the month of May, and you have to balance fuel and power use, taking a longer route will get you a higher number of ton-miles, and thus positive points. For example, for a very good score, you could ship grains from Bangor, Maine by sail to Troy, New York, all the way around the coast of New England and up the Hudson River. Since your fuel and energy inputs could be minimal or nothing in transit except through New York Harbor, docking, and undocking, you could rack up a very large score, even in a small vessel. If it takes you a week, you won't lose any points or place in the finish line, and with good planning you have up to a month. This also means that a path requiring the least climbing will also get you a better score. If you can use an electric vehicle with regenerative braking, and go principally downhill, you will decrease your grid-power requirements, and thus increase your overall score. If you are using a gas or diesel vehicle for even part of your voyage, using these efficiency-routed pathways of least resistance are similarly beneficial to your score: Every 7 fluid ounces of fuel is worth one point! 3. Charging From Isolated Sources Is "Free." While charging from the grid costs 5 points for each 10kWh of power used, charging from independent sources, such as isolated solar panels, wind generators, hand crank dynamos, or even micro hydropower generators costs nothing in points. While using a fossil-fueled generator or batteries charged from the grid to charge your vehicle would be disqualifying as simple attempts at avoidance and fraud, if the source of your power is fuel-free and not grid-connected, you can use it to an unlimited capacity without penalty. 4. People, Bikes, Pack Animals, and Sail Boats don't use fuel or grid power if well managed. Maybe something to note down, alongside the phone number to your local marina, bike club, and horse stables. 5. Woah, Slow Down Maurice! Speed requires extra energy, and this means more fuel burned. In fact, Extra-Slow Steaming is used on container ships when fuel is expensive because it saves so much fuel. A 10,000 TEU container ship burns about 325 tons of fuel per day at 24 knots, but only 100 tons per day at 16 knots. Simply by slowing down 33%, fuel consumption goes down by almost 70%. While slowing down will certainly save fuel, you will have to learn the ideal speeds for your own vehicle, as not all are the same. Depending on design factors, the most efficient speed for a particular arrangement of cargo and vehicle may be very different than what you expect, and may be found in a very narrow window. So, there's more than one way to get a better score in the grain race, without investing over half a million dollars in an electric Sail-Motorboat designed for Carbon-Neutral sail freight and a pair of electric trucks. In fact, many of these methods can be combined for even better scores in most cases. You can find more information on the Grain Race here. AuthorSteven Woods is the Solaris and Education coordinator at HRMM. He earned his Master's degree in Resilient and Sustainable Communities at Prescott College, and wrote his thesis on the revival of Sail Freight for supplying the New York Metro Area's food needs. Steven has worked in Museums for over 20 years. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

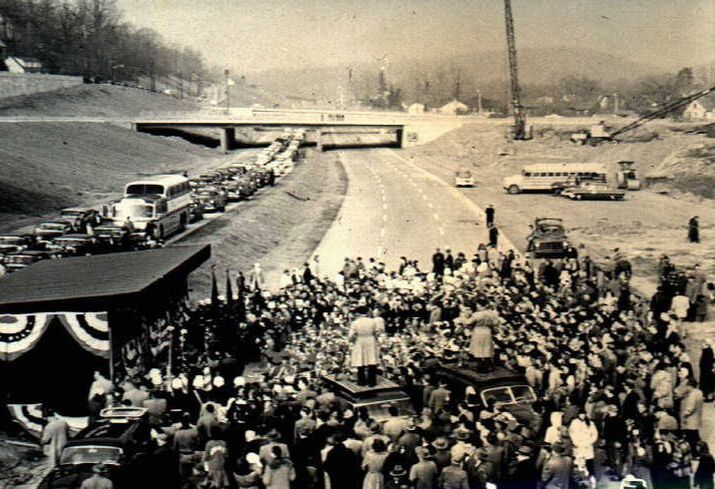

On December 15, 1955, the newly constructed Tappan Zee Bridge opened to the public. Construction began in 1952 and the bridge took 45 months to complete. It connected Nyack, NY in Rockland County on the west side of the Hudson River, and Tarrytown, NY in Westchester County on the east side of the river. It was part of a larger project constructing the Governor Thomas E. Dewey Thruway - one of the oldest interstate highway systems in the country and the longest toll road in the nation. Watch the film below, created in the 1950s and held by the New York State Archives, about the construction and opening of the bridge. The film features lots of historic footage of how construction battled and depended on water. The bridge opening was typical of many mid-20th century construction projects, featuring honored dignitaries giving speeches and throngs of people crowding to see and experience the new bridge first-hand.  December 15, 1955 South Nyack Celebration opening of the Thomas E. Dewey Thruway. Crowds gathered on a cold December 15, 1955 for the official opening of the Tappan Zee Bridge. There are flags, a color guard, and a band. Cameramen stand atop cars, surrounded by hundreds of spectators. Many cars and a bus are in line in the eastbound lane, ready to drive across the bridge. The bridge was named Tappan Zee after the Tappan tribe of Native Americans who once lived in the area - and for the Dutch zee, an open expanse of water. Later in 1994, the bridge would be renamed Governor Malcolm Wilson Tappan Zee Bridge in honor of the former governor. Photo by Dorothy Crawford, 1955. Nyack Public Library Local History Collection. The construction of the bridge dramatically changed the two communities it connected, both physically and demographically. Over 100 homes were removed or relocated via eminent domain in Nyack to make room for the Thruway and bridge, despite stiff opposition to the plan. Once the highway and the bridge were completed, both Nyack and Tarrytown, as well as neighboring communities, boomed with commuters and others seeking less expensive housing still within driving distance of New York City. To learn more about the controversies leading up to the construction of the bridge, a historical timeline, the architecture of the bridge, first-person accounts, and more, check out this online exhibit. The old Tappan Zee bridge was replaced with a new bridge and gradually demolished. Demolition was completed and the new bridge fully opened in 2018. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor’s Note: The following text is a verbatim transcription of an article featuring stories by Captain William O. Benson (1911-1986). Beginning in 1971, Benson, a retired tugboat captain, reminisced about his 40 years on the Hudson River in a regular column for the Kingston (NY) Freeman’s Sunday Tempo magazine. Captain Benson's articles were compiled and transcribed by HRMM volunteer Carl Mayer. See more of Captain Benson’s articles here. This article was originally published November 26, 1972. The lives of some steamboats are like people. They venture far from the land of their youth, never to return. This was the case with the steamboat “City of Kingston" which left the Hudson River to go all the way to the Pacific coast. The “City of Kingston” opened the season of 1889, as she had in her former years of service on the Hudson River, with a run up-river to Rondout shortly after the river was clear of ice. In 1889 this became possible on March 19. As events turned out, it was to be the start of her last season on the Rondout to New York run. During the summer of 1889, Captain D. B. Jackson, operator of the Puget Sound and Alaska Steamship Company, came east looking for a “propeller” suitable for his service. Apparently, the “City of Kingston” caught his eye and he made an offer to the Cornell Steamboat Company for her. The Price Was Right Cornell, it would appear, originally had every intention of operating the “City of Kingston" for many years more on her original route — and had made plans for a number of alterations to the steamer, including a new glass-enclosed dining room aft on the top deck. However, in those days of unfettered free enterprise, the Cornell Steamboat Company was not adverse to selling anything — if the price was right. The price apparently was right for at the end of September it was announced the “City of Kingston” had been sold for service on Puget Sound. The “City of Kingston", always a great favorite with Kingstonians, left Rondout at 6:05 p.m. on Sept. 30, 1889 on what was supposed to be her last trip. It was reported that a particularly large crowd gathered on the dock and gave her a hearty farewell. All the way down the river, her whistle was kept busy answering three blast - salutes of farewell from other steamboats. The following night, however, she came back in Rondout Creek briefly to unload supplies — and then went to Marvel's shipyard at Newburgh to be readied for her long voyage to the Pacific. At the shipyard, the red carpeting of the “City of Kingston’s” saloon was taken up and her furniture stowed. Her guards were reinforced with iron braces and heavy wooden slats to break up the force of ocean waves. Her open bow was enclosed, windows boarded up and water tight partitions installed on the main deck. Two large masts were stepped and rigged for sails. Before the Canal Finally, on Nov. 18, 1889 the “City of Kingston” passed New York City for the last time and headed down Ambrose Channel. Since 1889 was long before the digging of the Panama Canal, it meant the steamboat had to go down the entire coast of South America, through the Straits of Magellan at Cape Horn, and then up the west coast of South America, Central America, Mexico and all of the United States to reach her destination of Puget Sound. The “City of Kingston" arrived at Port Townsend, Washington, Feb. 27, 1890 after a safe and apparently relatively uneventful voyage. She had been 61 days at sea and her best 24 hour run had been one of 327 nautical miles. The remaining 30 days of her voyage had been spent in various ports taking on coal and supplies and at Valparaiso, Chile for engine repairs. Entering service on the west coast on March 15, 1890, her principal run was on the route between Tacoma, Seattle, Port Townsend and Victoria, B. C., although on occasion she also made runs to Alaska. The “City of Kingston” was to run successfully in this service for nine years. Early on a Sunday morning, April 23, 1899, the “City of Kingston’’ was inbound for Victoria from Tacoma, running through a light fog. At 4:35 a.m., just a few miles short of her destination, she was in a collision with the Scottish steamship "Glenogle’’ outbound for the Pacific. The “City of Kingston’’ was struck on the starboard side, aft of the fireroom and sank in three minutes. Boats from both vessels were put over and all 12 passengers and 60 crew members were saved. Her wooden superstructure, broken at two by the collision, floated off. A number of the “City of Kingston's” crew members when she was in service on the Hudson River went to Puget Sound and served on her there. One of these was John Brandow, second pilot on the steamer on her first trip to Rondout on May 31, 1884. By a quirk of fate, he was the pilot at the wheel at the time of her fatal collision 15 years later. Also, strangely, the steamboat's name remained unchanged during her years on the west coast. The steamboat named for the fine colonial city on the Hudson River proudly carried the name “City of Kingston” to ports 3,000 miles away and in service never envisioned at the time of her launching. After she sank, several of her crew members who had gone to the west coast returned to Kingston. One of them brought with him several small sections of her joiner work salvaged from the saloon of the sunken steamboat. The Cornell Steamboat Company, the “City of Kingston's” original owner, had several of these small panels put in oak frames and gave them to former officers of the steamer when she had been in service on the Hudson River. One of these was given to former First Pilot William H. Mabie. It is now in the possession of his grandson and my good friend, Roger Mabie of Port Ewen. AuthorCaptain William Odell Benson was a life-long resident of Sleightsburgh, N.Y., where he was born on March 17, 1911, the son of the late Albert and Ida Olson Benson. He served as captain of Callanan Company tugs including Peter Callanan, and Callanan No. 1 and was an early member of the Hudson River Maritime Museum. He retained, and shared, lifelong memories of incidents and anecdotes along the Hudson River. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

|

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 [email protected] Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |