History Blog

|

|

|

|

|

Editor’s Note: The following text is a verbatim transcription of an article featuring stories by Captain William O. Benson (1911-1986). Beginning in 1971, Benson, a retired tugboat captain, reminisced about his 40 years on the Hudson River in a regular column for the Kingston (NY) Freeman’s Sunday Tempo magazine. Captain Benson's articles were compiled and transcribed by HRMM volunteer Carl Mayer. See more of Captain Benson’s articles here. This article was originally published August 14, 1977. Almost from the beginning of steam navigation, there have been shipyards along Rondout Creek. Probably the biggest day in the creek’s history occurred on September 30, 1918, when the largest vessel built along the Rondout hit the water for the first time. Back in World War I, steel was in short supply and the federal government decided to build oceangoing freighters of wood. Four of these were to be built at the shipyard on Island Dock. The first ship to be launched was named “Esopus” and the event, based on estimates made by the Daily Freeman at the time, was witnessed by 15,000 people — more than half the population of Kingston and the immediate surrounding area. In that era of nearly 60 years ago, Rondout Creek was a busy place. In addition to the ocean freighters being built at Island Dock, the C. Hiltebrant Shipyard at Connelly was building submarine chasers and the other yards were busy building barges to carry the Hudson’s commerce. The creek echoed with the sound of caulking hammers, the whine of band saws, and the whir of air drills and hammers. The "Esopus” was the largest vessel, then or since, to be built along the Rondout, and her size, together with the intensity of the war effort, created a great deal of local interest in the ship. It had been rumored the launching would take place in mid-September. When it did not, this only piqued the interest of area residents. Finally, it was announced in the Freeman that September 30 was to be the day. Spectators began to arrive early and crammed all vantage points. Grandstands had been erected and benches set up for the people lucky enough to get on the Island Dock. Up on Presidents Place and in the area known as the “Ups and Downs” at the end of West Chestnut Street, there were large groups of people to get a birds-eye view. Along the South Rondout shore, people were in rowboats and the steam launches and yachts of old. Even the abutment on which today stands the south tower of the Rondout Creek highway bridge, completed just prior to World War I, was crowded with people. It is my understanding there were even some doubting Thomases among the estimated 15,000 spectators. Some were of the opinion the "Esopus” was so big she would stick on the launching ways, while others thought she might tip over on her side when she hit the water, or go right across the creek and hit the South Rondout shore. I have heard there were even small bets among some people that one of these possibilities would occur. As the launching hour approached, the sound of music from the Colonial City Band, on hand for the occasion, filled the early autumn air. The music was punctuated by the sound of workmen’s mauls driving up wedges to remove the last remaining blocks from beneath the ship. The launching ways had been angled with the creek’s course to gain additional launching room. When all was in readiness, Miss Dorothy Schoonmaker, daughter of John D. Schoonmaker, president of the Island Dock shipyard, broke the traditional bottle of champagne on the ship’s bow, and the “Esopus” started to slide down the greased ways. As soon as she started to move, the gentle September breeze caused the ship’s flags and bunting to wave, and bedlam broke loose. It seemed as if every steam whistle along Rondout Creek was blowing at once. The Cornell tugboats “George W. Pratt,” “Rob” and “Wm. S. Earl" were on hand to take the “Esopus” in hand when she was waterborne. The steam whistles of this tugboat trio led the noisy serenade, together with the shipyard whistles at Island Dock and Hiltebrant’s, and the shrill whistles of the small old-time steam launches present for the event. The steeple bells of Rondout’s churches were also ringing and added to the festive air. It was a perfect launching and an impressive sight. It seemed that even nature smiled that day — so long ago that few today remember — for the weather was perfect. Even after the whistles quieted down, from way down the creek where the Central Hudson Line steamer "Homer Ramsdell” lay at her berth near the foot of Hasbrouck Avenue came the sound of her soft steam whistle still blowing a salute of good luck to the “Esopus.” And the ferryboats “Transport” and the little “Skillypot” were joining in. Finally, the “Pratt,” “Rob” and “Earl” had the "Esopus” securely moored at Island Dock, and peace and quiet returned to Rondout. As the crowds of people began to disperse, the band saws and air drills could again be heard as the shipyard workers resumed their work, both on the “Esopus” and on her sister ship that was to be called the “Catskill.” After several more weeks of completion work, the time came for the “Esopus” to leave the Rondout Creek forever. This occasion also drew crowds of people to the creek to witness her departure. The ship was completed at Kingston except for the installation of her engine and boilers. She was to be towed to Providence, Rhode Island, where these components would be installed and the vessel readied for sea. On the day of departure, people had started to gather at daybreak at vantage points along the creek and on top of the buildings along Ferry Street, for the newspaper had said she would leave early. However, it wasn’t until about 9 a.m. that the Cornell tugs “Rob” and “Wm. S. Earl” were seen heading up the Rondout to take the “Esopus” in tow. This pair of tugboats was to take the ship to the river, where the big Cornell tugboat “Pocahontas” was to take her to New York. The “Earl,” in charge of Captain Chester Wells, put her hawsers on the bow of the “Esopus” to pull her, and the “Rob,” in charge of Captain George “Bun” Gage, lay along her starboard quarter to both push her and act as a sort of rudder. As they pulled away from the yard of the builder of the “Esopus,” the steam whistle of the Island Dock began to blow farewell. Over in Connelly, the steam whistle of the Hiltebrant shipyard joined the serenade. As the “Esopus” moved sedately down Rondout Creek toward the Hudson, all the vessels along the creek with steam on their boilers joined in whistle salutes of goodbye and good luck. At the Central Hudson Line wharf between the foot of Broadway and Hasbrouck Avenue lay the big steamer “Benjamin B. Odell.” The “Odell’s” pilot, Richard Heffernan, was on top of the pilothouse as the “Esopus” passed, pulling on the cable connected to the large commodious whistle and he kept pulling it to the whistle’s full steam capacity. Even the trolley cars along Ferry Street were ringing their bells. At that time, Rondout Creek sort of resembled a home for old steamboats. At the foot of Island Dock lay the big sidewheel towboat “Oswego” built in 1848. At the Abbey Dock, east of Hasbrouck Avenue, lay the old Newburgh-to-Albany steamer “M. Martin,” which at one time during the Civil War had served as General Grant’s dispatch boat. Farther down the creek at the Sunflower Dock lay the old queen of the Hudson, the “Mary Powell.” Now, on all three, after over half a century of service on the Hudson, their boilers were cold and their whistles were silent. As the "Esopus" neared Ponckhockie, the large whistle on the U.& D. Railroad shops and the whistle of the old gashouse blew long salutes of goodluck and happy sailing. Finally, as she approached the mouth of the creek, Jim Murdock, the keeper of Rondout lighthouse, rang the big fog bell in a final farewell to the “Esopus." When she reached the Hudson, the “Pocahontas” took the “Esopus” in tow and started the trip to New York. Years later I was pilot on the “Pocahontas,” and her chief engineer, William Conklin, told me about the 1918 trip down the river. Chief Conklin was a great man for detail. He said that when they got to the Hudson Highlands, between Cornwall and Stony Point, it was the time of evening when the nightly parade of nightboats made its way upriver — the passenger and freight steamers bound for Kingston, Saugerties, Catskill and Hudson, Albany and Troy, as well as tow after tow. That was when the Hudson River was really busy with waterborne traffic. Bill went on to tell me the “Esopus” towed like a light scow, following the “Pokey” without any trouble at all. They arrived in New York in the early morning and a big coastwise tug was waiting for them at Pier 1, North River, to tow the “Esopus” out Long Island Sound. The orders from the Cornell office were for the “Pocahontas” to stay with the tow up the East River through Hell Gate and then call the Cornell office for further orders. After passing through the Gate, the "Pocahontas” let go, saluted the "Esopus" three times and returned to the Hudson. After that, I never knew for sure what became of the “Esopus.” It would be nice to be able to say she had a distinguished career in war and a long, profitable one in peace. Ships like the “Esopus,” however, had been an emergency measure. World War I was over before she saw much service and apparently they found little use in the years that followed. It is my understanding the “Esopus” was the only one of the four to be built on Island Dock that was completed. Her sister, the “Catskill,” was launched but never finished, and construction of the other two was stopped and they were dismantled. In the 1920’s and early 30’s there used to be ships like the “Esopus” in the backwaters of New York harbor lying on flats and abandoned, but I never saw any names on them. Gradually they rotted away with only a few watersoaked timbers remaining. If one of these should have been the bones of the “Esopus,” it would have been a sad end for a ship that was cheered by some 15,000 people when she was launched on Rondout Creek nearly 60 years before. AuthorCaptain William Odell Benson was a life-long resident of Sleightsburgh, N.Y., where he was born on March 17, 1911, the son of the late Albert and Ida Olson Benson. He served as captain of Callanan Company tugs including Peter Callanan, and Callanan No. 1 and was an early member of the Hudson River Maritime Museum. He retained, and shared, lifelong memories of incidents and anecdotes along the Hudson River. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

0 Comments

This coming Saturday is the Conference on Black History in the Hudson Valley, so we thought this Media Monday that we would share this award-winning documentary film. Completed in 2018, "Where Slavery Died Hard: The Forgotten History of Ulster County and the Shawangunk Mountain Region" is the creation of the Cragsmoor Historical Society and was co-authored by archaeologists Wendy E. Harris and Arnold Pickman. It is a common misconception that slavery did not exist in the North, or if it did, it "wasn't as bad" as in the South. This is false. New Amsterdam had enslaved people since the beginning, as slavery was a cornerstone of much of Dutch colonialism. And in the mid-18th century, more New Yorkers enslaved people than almost any other American colony. New York was one of the last Northern states to abolish slavery (New Jersey had "apprenticeships" until 1865). New York City was staunchly pro-slavery, even during the Civil War, but upstate New York was a hotbed of abolitionist activity, from Western New York to Albany. "Where Slavery Died Hard" chronicles the role of slavery in Ulster County, including the story of Sojourner Truth, who was enslaved in Port Ewen (just across Rondout Creek from the Hudson River Maritime Museum) and elsewhere in Ulster County. If you'd like to learn more about Black History in the Hudson Valley, you can attend the conference (in-person and virtual options available!), check out our past Black history blog posts, or visit the Hudson Valley Black History Collaborative Research Project and its in-process collection of Black history resources and research specific to the Hudson Valley. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

In May of 2022, the Hudson River Maritime Museum will be running a Grain Race in cooperation with the Schooner Apollonia, The Northeast Grainshed Alliance, and the Center for Post Carbon Logistics. Anyone interested in the race can find out more here. The Great Grain Races from Australia to England in the early 20th century were a relic of the Golden Age of Sail, and were informal races between sailing vessels plying the last economically viable trade route for Sail Freight. Lasting from the 1920s to the late 1940s, the Grain Races weren't quite as intensive as the Tea Races, which will be the subject of a later post, but still are a set of impressive achievements. Since these are what the current Northeast Grain Race is based upon, they are worth a bit of explanation. The Wheat Trade from Australia to England was a long distance trade which required a large amount of fuel for a steamer or motor vessel to undertake, meaning that the labor costs of a sailing vessel weren't an issue in competition. Further, the journey was going to be relatively slow no matter which method was used to transport the grain, so shippers and receivers would sacrifice speed for lower costs. Thus, sailing vessels, principally from Gustaf Erikson's fleet from the Aland Islands in Finland, could ply this trade profitably. From the 1920s to 1949, with the exception of the WWII years, the grain races were held informally. While not everyone started or ended at the same port, the goal was to have the shortest passage possible with the least cost in damaged equipment. The informal nature of the competition was due in large part to the lack of a bonus for arriving early with a cargo: The prize was principally fame for the ship and her crew, not fortune; those betting in coffee houses ashore stood to make more than the ship or sailors on any wagers. According to Georg Kahn's book The Last Tall Ships most of the passages were about 100 days from Australia around Cape Horn to England. The shortest was a passage of 83 days by the ship Parma in 1933, which is an impressive passage time. The fastest ship overall, with 7 voyages averaging 99 days each, was the Passat. This time period, however, was one of undermanned, mostly older vessels running this trade. While a fast passage was desirable, it was more important to avoid expensive repairs, whether that be to rigging, hull, or sails, because the margins for the trade were very narrow. Arriving late with a cargo of grains was not a great loss to the shipper or receiver in most cases, thus the ships could take up to 130 days or more to make the journey, if needed. The under-strength crew was partly an effort at cost savings as competition from what we would now consider "Conventional Shipping" became ever stronger, but also a result of the scarcity of skilled windjammer sailors. Standard Seamanship For the Merchant Service (page 13-17) from 1922 remarks upon this in the chapter on type of vessels, and the death of working sail is taken as essentially inevitable in that same manual: "Nowadays it is a hard problem to find enough able-bodied seamen to man a craft of this type properly. This accounts for the fact that many a square rigger loses half her canvas before a green crew is broken in…. The coming sailing vessel of the future, however, is the auxiliary; no matter what her rig may be. A vessel fitted with crude-oil engines, placed aft for convenience, offers a decided advantage to navigators and one that is beginning to be appreciated…. Many authors dismiss sail with a few sad words of farewell." Sail Freight had been slowly declining since the 1870s due to increased fuel efficiency and reduced cost in steam shipping, the proliferation of larger steam ships, and the opening of canals which shortened journeys for steam ships, but were unsuited to sailing vessels. The destruction of sailing ships by U-Boats in the First World War due to their limited ability to avoid torpedoes also contributed to the decline of Sail Freight in the Atlantic and Mediterranean. There are some lessons to be learned from these races. First, people will take interest in these types of competitions, and will rise to the challenges offered. Second, many sustainable transport systems will likely first find viability in very long distance transportation, as opposed to the short distance we are competing at in the current grain race. Where distances are long and fuel expensive, Sail Freight is likely to revive especially well. In cases where the addition of some modern technology to sailing vessels to automate or simplify crew functions, a smaller crew would mean lower expense for operation, making sail freight more competitive. With the addition of electric motors, moving through a calm or around areas like The Cape Of Good Hope where the winds can be contrary can be transited under power, likely shortening transit times, the main advantage cited in the manual above for auxiliary sailing craft. The Northeast Grain Race is a bit more of a game than a strictly-defined race, due to the points-based system and permissive rules on vehicles which can enter, but is very much in the spirit and tradition of the Great Grain Races of up to a century ago. By looking for inspiration in the past, we can certainly find models for making our future a sustainable and entertaining one. You can find more information on the Grain Race here. AuthorSteven Woods is the Solaris and Education coordinator at HRMM. He earned his Master's degree in Resilient and Sustainable Communities at Prescott College, and wrote his thesis on the revival of Sail Freight for supplying the New York Metro Area's food needs. Steven has worked in Museums for over 20 years. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's note: Many thanks to volunteer researcher George A. Thompson for finding and transcribing these articles describing early commuting. These articles were originally published in the Rockland County Journal. FACILITIES FOR TRAVEL. The facilities for travel along the Hudson next season will, by the addition of the trains of the West Shore road, be very large. We have only to refer to some of them to show that travel must indeed be very large in order that all the lines can be made to pay. In the lower Hudson there will be three lines of steamers between Peekskill, Nyack and New York, a steamer will run as usual between Haverstraw and Newburgh, a steamer will run two or three times a day between West Point and Newburgh, a steamer will run between Newburgh and Poughkeepsie, two steamers will run between Newburgh and Albany, three steamers will run between Poughkeepsie and New York, three steamers will run between Rondout and New York, one steamer will run between Saugerties and New York, two between Catskill and New York, two between Catskill and Albany, two between Coxsackie and New York, four between Troy, Albany and New York, also in addition the two day boats between New York and Albany. These make twenty-seven steamboats that will run night and day, saying nothing about handsome barges. Add to these twenty six trains on the N. Y. C. & H. R. R. R., and twenty trains on the West Shore R. R., making forty-six trains in all. The twenty seven steamboats have a carrying capacity of 10,000, and the trains, taking six cars to a train, a carrying capacity of 10,560, making a grand total of carrying capacity, by both cars and boats of 26,650 people. — Poughkeepsie Eagle. Rockland County Journal (Nyack, N. Y.), February 24, 1883 THE TRAVEL INCREASING. COMMUTERS ARE NOW COMING BACK TO NYACK. The Saturday Half Holiday Train Will Be Put on the Latter Part of May. Traveling is steadily increasing to and from Nyack, and in a few weeks at the most the trains and boats will be carrying their full quota of passengers. "The travel on the Northern Railroad," said Mr. William Essex, station agent at Nyack, to a reporter, "is now slightly increased over that of last year at this time, and I think the prospects are good for an increased number of passengers during the season. A number of commuters are already back from the city in their Nyack homes, and most of them travel up and down daily. A little later more cars will have to be put on the trains to accommodate the passengers. "I have not yet heard of any change in the time-table," continued Mr. Essex, "and I do not anticipate any. The present time table appears to give general satisfaction. The Saturday half-holiday train will be put on the latter part of May." Travel in other directions is also on the increase. The Chrvstenah carries a goodly number of passengers to and from the city daily, and the number is steadily growing larger. There are more daily passengers to and from the West Shore station at West Nyack than there have been during the past season, and the Nyack and Tarrytown ferry is also doing an increased business. Soon the tide of Summer travel will set in in every direction, and Nyack will probably have its full share of those who come and go. Rockland County Journal (Nyack, N. Y.), May 4, 1895 If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Relive the historic return of Charles Lindbergh to New York from the deck of the S.S. "Dewitt Clinton". Other vessels featured in this vintage film include the Steamboat "Hendrick Hudson", S.S. "Rochambeau", and the S.S. "Berlin". On June 13, 1927 25-year-old Charles Lindbergh returned to New York from the first solo transatlantic flight from New York. Lindbergh worked as a U.S. Postal Service pilot as well as a barnstormer. Barnstormers traveled the country performing aerobatic stunts and selling airplane rides. Lindbergh decided, with the backing of several people in St. Louis, to compete for the Orteig Prize—a $25,000 reward put up by French hotelier Raymond Orteig for the first person to fly an airplane non-stop from New York to Paris. Lindbergh, at the age of 25, and the Spirit of St. Louis took off from a muddy runway at Long Island’s Roosevelt Field on the morning of May 20, 1927. He left the plane’s side windows open so that cold air and rain would keep him alert on the 33-1/2 hour flight. The sleep-deprived Lindbergh later reported he had hallucinated about ghosts during the flight. Read more about Lindbergh and the flight here: https://www.history.com/topics/exploration/charles-a-lindbergh If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

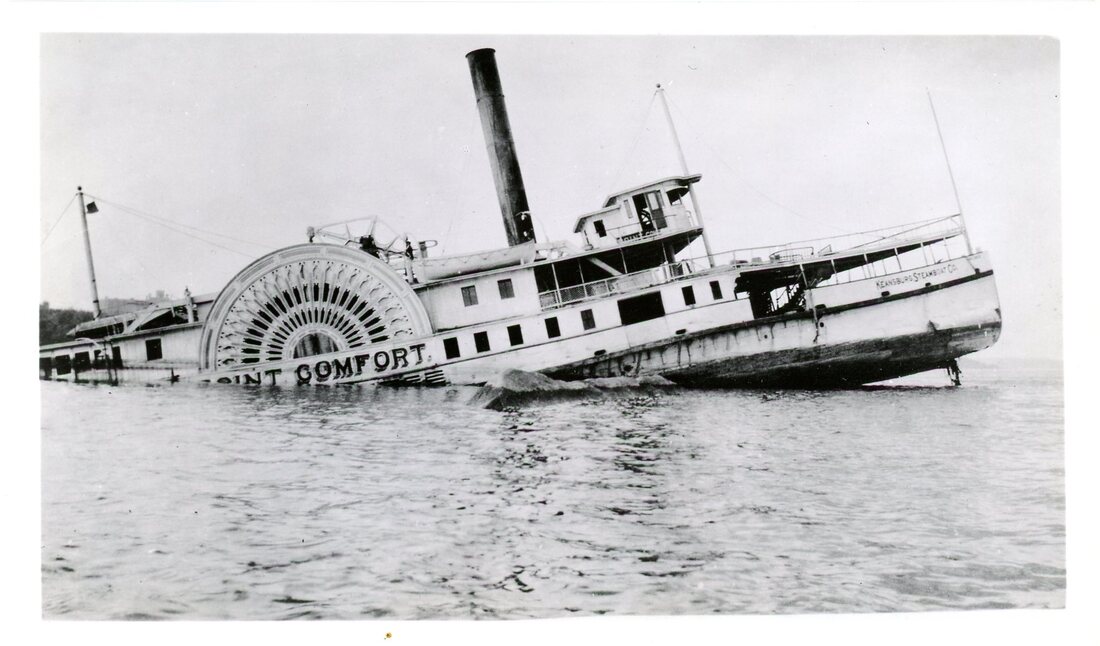

Editor’s Note: The following text is a verbatim transcription of an article featuring stories by Captain William O. Benson (1911-1986). Beginning in 1971, Benson, a retired tugboat captain, reminisced about his 40 years on the Hudson River in a regular column for the Kingston (NY) Freeman’s Sunday Tempo magazine. Captain Benson's articles were compiled and transcribed by HRMM volunteer Carl Mayer. See more of Captain Benson’s articles here. This article was originally published September 17, 1972  The "Point Comfort" wrecked on Esopus Island. When the steamer ran aground, she was headed due south. The ebbing tide, before the steamboat finally settled on the bottom, pivoted the vessel around 135 degrees — until she faced in a north-easterly direction. Donald C. Ringwald Collection, Hudson River Maritime Museum On the night of Sept. 17, 1919 —53 years ago tonight — the steamboat “Point Comfort" ran aground on Esopus Island and became a total loss. Her wreck remained there until it was finally removed in the early 1930's. On the night of the accident, the steamer had been bound for Catskill and her presence on the river was due to a great reduction in service by the Catskill Evening Line. The Catskill Evening Line was one of the first of the Hudson River steamboat companies to run into financial difficulties. In early 1916, control of the steamboat line was acquired by the Hudson River Day Line, which operated the company until the end of the 1917 season. During 1916 the Line's passenger steamers "Onteora’’ and “Clermont” ran to Troy and in 1919 were layed up, one steamer at Catskill and the other at Athens. The Catskill Evening Line did remain in business at a greatly reduced level, operating a single freight steamer — the “Storm King.” Some businessmen at Catskill, however, were dissatisfied with the service. They wanted service every night, which the "Storm King" by herself could not do. The group of businessmen banded together and chartered a steamboat from the Keansburgh Steamboat Company in New York harbor called the “Point Comfort." The “Point Comfort’’ had originally been named the “Nantucket" and had been built in 1886 for the route between New Bedford, Woods Hole, Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket. She operated on that route for 26 years, year round, and she had a reputation of being a very good boat in salt water ice. In 1913 she was purchased by the Keansburgh Steamboat Company, which changed her name to “Point Comfort” and — until 1919 — she was operated in and around New York harbor. A Trim Sidewheeler When purchased by her new owners in 1913, her second deck was extended out to the bow stem and other alterations were made to the steamer. She was a trim looking sidewheeler, looking somewhat like the Hudson River steamer “Jacob H. Tremper," with about the same speed. When the “Point Comfort” was chartered by the Catskill people in September 1919, she made one round trip to Catskill before her fatal accident. On her second trip, on Sept. 17, 1919, she left New York with a large load of sugar and other freight for Catskill and Athens. As told to me by a man who was on board the “Point Comfort” that fateful night, the day was one of those of late summer that had been very clear, the sun warm, but quite cool in the shade. On such a day, rivermen usually predict that after midnight banks of fog will start to appear where creeks run into the river and around flats. When the “Point Comfort” left the harbor, the other river night boats were also underway for Albany and Troy and the Central Hudson steamers to Newburgh, Poughkeepsie and Kingston. Being much faster, they soon left the “Point Comfort” astern. As it was related to me, banks of fog were encountered in the Highlands north of West Point and the night turned very cool. At first, the pilot house crew of the “Point Comfort" thought they would tie up at the recreation pier at Newburgh. At Newburgh, however, the weather cleared and they decided to keep on going. When they reached Crum Elbow, the steamer ran into another fog bank and they thought about tying up at the Hyde Park steamboat dock. The river, though, was up to its old tricks and off Hyde Park it again cleared. They keep going. Off Esopus Island the “Point Comfort" again ran into fog. About a half mile above the island, a decision was made to turn around and go back to Hyde Park until the fog lifted, since a good echo from a steam whistle is hard to get on going around Esopus Lighthouse, the lighthouse being so far from shore. On turning around in the fog, on board the steamboat they thought it was still flood tide. Instead it was slack water. On the way back down the river, it was the intention of the men in the “Point Comfort's” pilot house to pass to the west of Esopus Island. Because of the slack water, they were further downstream than they thought. They were also too far to the east. Going along at about 10 miles per hour reduced speed, the steamer piled up on the rocky reef just off the north end of the island. At the time they were headed due south. When the steamboat's stern settled in deep water and the ebb tide started to run, the tide turned her so bow pointed east, as if she had been going across the river instead of down stream. No one was injured in the mishap and the crew put over a life boat and rowed to Hyde Park. The ‘‘Point Comfort" lay in the position she ran aground and her wooden superstructure gradually disintegrated. Parts of it were removed by salvage men, some of it was later burned and the rest was chewed away by drifting winter ice. The “Point Comfort’s” boiler, remains of the engine and paddle wheels remained on the rocky ledge until about 1930. It was right off "Rosemont," the estate of the late Judge Alton B. Parker at Esopus, and was a recognized eyesore. At that time, Mrs. Parker wrote a letter to Franklin D. Roosevelt, then Governor of New York State, to ask if something could be done to remove the remains of the wreck. He was able to influence the Army Corps of Engineers to take action on the request. Gov. Roosevelt's reply to Mrs. Parker is, I believe, in the Governor's Room of the Senate House Museum on Fair Street. The Army Engineers removed the visible remains of the wreck of the “Point Comfort” and took them up to the Erie Barge Canal. There they were dumped behind Lock 10 at Cranesville, far from the salt water those old paddle wheels had churned in summer and winter on the old “Nantucket's” trips between Nantucket and the mainland of New England. Still today, at very low water, one can see parts of her old strong ribs, part of the keel and iron rods from her spars rusting away between the rocks on the north end of Esopus Island. AuthorCaptain William Odell Benson was a life-long resident of Sleightsburgh, N.Y., where he was born on March 17, 1911, the son of the late Albert and Ida Olson Benson. He served as captain of Callanan Company tugs including Peter Callanan, and Callanan No. 1 and was an early member of the Hudson River Maritime Museum. He retained, and shared, lifelong memories of incidents and anecdotes along the Hudson River. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's note: Many thanks to volunteer researcher George A. Thompson for finding and transcribing article describing a cruise on a Hudson River House-boat. This article was originally published as "A Cruise on a Hudson River House-boat" written by Jesse Albert Locke in the Godey's Magazine on August 5, 1893. A CRUISE ON A HUDSON RIVER HOUSE-BOAT. By Jesse Albert Locke ["Tom Perkins" invites "J. S. Wellington" to join him and two other friends on a cruise on a house-boat he has designed and built; Wellington declines, supposing it won't be much fun.] Two years ago a young physician in New York was trying to puzzle out the problem of his summer holiday, Where should he spend the two or three weeks he could take for recreation? On a certain hot afternoon in July, as he sat in his office thinking of the matter and longing for a breath of country air, an invitation to a decision arrived. It was in the form of the following note, characteristically laconic, from a friend who lived a few miles up the Hudson: Riverview-on-Hudson, July 20, 1893 Dear Wellington: I start August 5th on a house-boat cruise. Party of four. Will you join us? Say yes and say it soon. Come up here the night before. Yours cordially, Tom. This brought an immediate reply. "Riverview-on-Hudson, "July 22d. "My Dear Wellington: I am not at all willing to count me out. You must join us on our trip. You know how I hate letter-writing, so a proof of my desire for your company will be the long and full explanation which follows. In fact, I thought I had told you all about it before, but you are quite in the dark, I see. "I am inviting you to no experiment. I built my house-boat and made a trial-cruise in her last summer. It was a howling success. Jack Dunham, who went with me, is wild to go again. Let me tell you how I worked out my idea. "Living in a Hudson River town, I have been on the water a great deal ever since I was able to walk. I have had numerous sail-boats of different sizes, but for some time I had been wishing I had some sort of a craft roomy enough to cruise in with a small party of friends. A large yacht I could not afford, and so I conceived the idea of a house-boat, which I finally worked out to my satisfaction. "I found that to be a complete success my boat must have five points of advantage. First, it must be adapted to these waters. The English house-boats might do on a quiet stream like the Thames, but they would not be suitable for traversing the Hudson. The second thing to be secured was sufficient room. I wanted enough space to allow four or five persons to live aboard comfortably. Next, the boat (whatever it was) must be safe. I could not ask friends to sacrifice pleasure and peace of mind on a really dangerous craft. "It must also be, in some degree at least, self-propelling. This would enable me both to take advantage of the opportunities for being towed, and on the other hand to be independent of towing, when I wished. I wanted to be able to leave the channel and run into shallow water alongshore whenever desired. "Lastly, my boat (if it came into being at all) must be inexpensive. Some very costly house-boats have been built for Florida waters. One is said to have cost $40,000. It is rumored that a syndicate has been formed to build and rent house-boats for summer use, each boat to cost from $5,000 to $15,000. But these are not to be self-propelling. They must be towed to some one place and anchored there. Besides, I had to reckon in hundreds -- not thousands -- of dollars. "As to my success in realizing my ideal, I am happy to say that I have secured every one of these five points. My boat, Satan, only cost me $600, and it is roomy, safe, self-propelling, and easily navigated. Let me describe its construction in detail. "I first build a large flat hull, 27 feet 9 inches long, and 9 feet wide. Its draught of water is only 27 inches. An 18-inch heel runs the full length. On this hull I built the cabin, leaving deck-room fore and aft. There are six feet of head-room in the cabin. A heavy guard-rail or buffer, a foot wide, runs all around the boat to protect it in the necessary impact against canal-boat or dock. There are two spars, the mainmast having a lateen-sail, and the jigger the ordinary fore and aft rig. The steering is done by a tiller in the usual way. Under the forward deck slides an ice-box which will hold three hundred pounds of ice. Two large lockers also slide in like drawers. Under the stern deck is a bunker for charcoal on one side, and on the other a storage locker for tools, rope, putty, etc. The roof of the cabin forms an upper deck, and an awning is stretched over it while at anchor. There are two awnings also for the fore and after decks. "The Satan really could no be upset. The only danger, practically, is that of being becalmed in the channel at night, and so being in the way of the great steamers and the tows, which are constantly going up and down. But this can be avoided by a little forethought. It requires only one man beside the sailing-master to manage the boat. "You see how much I have secured. I have the cabin space of an eighty-foot yacht at the cost of only $600 instead of $5,000. I can go where yachts cannot go, in the swallow waters and lagoons alongshore. On the other hand, I am not bound to stay in any one place when circumstances make it desirable to more. If, for example, a cloud of mosquitoes settles upon us., we heed not suffer mild martyrdom because we cannot get towed off, as would be the fate of persons on one of the permanently anchored house-boats. We simply put up sail and go elsewhere. All the pleasures of out-door life -- the air, scenery, sport, etc. -- are ours, with enough novelty and change to keep up the interest. "If the wind fails it is very easy to get towed. There are three regular towing lines (besides some smaller ones) which start from New York every day on their way up the Hudson, and are due at certain places at certain definite hours. There are also steam canal-boats that will take one on. "There is quite a choice in routes. My boat is adapted to any large river like the Hudson, or to any lake or canal. In a canal, of course, the spars must be taken out. I intend this time to go up the Hudson to Troy, through the Champlain Canal to Lake Champlain and back again. "Think over all this, take a good look at the photographs of the Satan which I send, and then let me know whether we may expect you on the 5th. I feel sure you will come. "Yours cordially, "Tom Perkins," The doctor telegraphed his acceptance and went to buy some outing clothes. He left town, promising his medical chum (who was to look after his practice for him) some account of his new experience if he felt like writing. These were Dr. Wellington's letters. "Somewhere up the Hudson. "August 8, 1893. "Dear Chummy: You see how prompt I am. This is only our third day out. We are lying at anchor this morning will all the awnings spread. I don't know exactly where we are -- geographically -- but the little cove with its pebbly shore, the restful green of the wooded point, the shimmering river beyond, and above all, the delicious sense of its not making any difference in the world where we may be -- all this is enough to make it Elysium. City life and bricks and mortar belong to a stage of inferno from which we have escaped. "We have a jolly, tight little home in the Satan. Why Perkins, captain and owner, dubbed his craft thus is not apparent. There are no satanic qualities about the boat. Perhaps he had the Oriental idea of casting an anchor to windward, propitiating the genius of the underworld by an outward show of respect as a security against disaster. "Our cabin is one large room, from which a small corner has been cut off for a kitchen. There is a door at each end, one opening upon the fore and the other upon the after deck. Everything is very 'ship-shape.' The captain has mastered thoroughly the necessary nautical science of stowing things snugly. On the partition which cuts off the kitchen is a buffet where every cup and plate has its own place in a rack. Our dining-table is a folding affair, like a lady's cutting table, and is fastened flat against the wall between meals. There are two windows on each side, all having dark-green shades and dotted Swiss curtains. Between each set of windows is an upright locker, and above the latter a swinging brass yacht-lamp. The floor is covered with linoleum, and Japanese rush mats. Silk yachting flags, photographs, and Japanese fans adorn the walls. There are four camp-chairs -- with backs, fortunately. "The kitchen is a multum in parvo wonderfully worked out. Our stove is a miniature range, such as is made for boats, and has all the conveniences. It works to perfection. The fuel is charcoal, which costs a dollar a barrel. The captain says that it takes from one and a half to two barrels a week. The bunker holds four barrels. It is a great improvement upon an oil-stove, which is usually very disagreeable. The odor of the oil generally pervades the boat, and everything is covered with soot. "The kitchen utensils hang on hooks against the wall, and underneath them is canvas stuffed with cotton, so that when the boat is in motion one's nerves are not irritated by rattling and banging noises. Rows of canisters for flour, coffee, tea, etc., and a good assortment of canned goods find places on the corner shelves. "I am cook. We debated at first whether the office should be hold in rotation or not, and concluded that things would run more smoothly if each man had his own duties and stuck to them during the trip. I have had some experience in camp-cooking, and I took a few additional lessons from my landlady before I left town. I also invested in one of the simple cook-books intended for 'young housekeepers,' I have done very well. After an ineffectual attempt to make an impression upon one, the captain moved that they be reserved for ammunition in case we should be attacked by river pirates. This was quickly seconded and carried. That, however, has been my only failure. Otherwise I am a culinary success. "It is very easy to get provisions. We started with three hundred pounds of ice, and we can renew our supply at any time from the ice-houses along the river, or from the floating ice-barges which are constantly floating up and down. Fresh meat can be obtained at the villages and small town where we stop frequently for a little excursion ashore. "As to the rest, we need never want anything very long before three toots from a steam-whistle announce the approach of a 'bum-boat.' A bum-boat (should you not know the term) is really a country general store afloat -- a small steam-tug which cruises about, supplying the wants of the canal-boat men. The whistle has hardly died away before the bum-boat is fastened alongside, and we are invited aboard. All around the walls of the cabin are doors which, when flung open, reveal a complete stock of groceries neatly arranged on shelves. There are also miscellaneous articles and plenty of fresh vegetables which the bum-boat traders have obtained by barter from the farmers along the river. There is always a large stock of 'wet goods,' which the canal-men buy in great quantities. This, however, need not alarm the temperance enthusiasts, as the supply consists almost exclusively of ginger-ale and sarsaparilla. "Now for our daily routine. Breakfast is a movable feast. The rising hour means when the cook gets up, which is generally somewhere in the neighborhood of eight o'clock. We sleep on woven-wire cots, two feet two inches wide. Solid immovable berths are less comfortable and take up too much cabin-room. While I light the fire and begin to cook breakfast, 'Rocks" (as we have nicknamed Jack Dunham, who is always imagining that we are running on a reef) puts the cabin in order. The four cots, folded up and laid one upon another make a comfortable divan during the day. Four cretonne-covered pillows give it a cozy look. "After breakfast, the captain and Henry (the two assigned to outside work) wash the decks, hoist sail, get up the anchor, and we are off. Meantime I as chef, take my ease, while 'Rocks' washes the dishes and sweeps the cabin-floor. "If there is a good wind we then sit out on deck and take a morning smoke, while we bother the captain with ignorant nautical questions as to why he should point his course in such a direction, or where he expects to take us. If there is no wind, we lie at anchor, spread the awnings, read, talk, and amuse ourselves in various ways. "Lunch comes at one or two -- a cold meal if we happen to be sailing at the time. Then, generally, a siesta. At four o'clock all are overboard for a swim. Supper is always eaten by day-light, lest the lighting of lamps should draw in mosquitoes. We never sail at night, but always anchor near the shore before sundown. Supper sometimes has an elaborate dinner menu, and sometimes it is a very simple meal. You have no idea what delectable things I have been able to concoct on a chafing dish. 'Rocks' sighs daily for Welsh rabbits, but the captain is insistent about some things and will allow no cheese on board. He contends that it has such a penetrating quality that a single piece will make its presence felt for the rest of the voyage. "At night we sit on the upper deck, smoke, sing, listen to Henry's guitar, watch the night-boats on the river, and commiserate the poor devils like you who are sweltering in town. At 9:30 p. m. the cots go up, and all hands turn in for the night. "The cruise is a grand success. Vive le Satan! "Yours fraternally, "J. S. Wellington." ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- "In the Champlain Canal, "August 21, 1893. "Dear Chummy: My career has not come to a watery end in spite of my long silence. 'Time was made for slaves.' A holiday cruise without a lofty disregard for time would be as flat as an unsalted dish. "The last two weeks have been full of novel experiences. The life of the anal-boat people is full of picturesque interest. I had never come in contact with it before. On our way to Albany, the captain of the canal-boat by which we were being towed invited us to dinner. We found him, as we found most of the others of his class, somewhat bluff and rugged, but as manly, honest, and good-hearted a fellow as one could wish to meet. I was surprised to find that some of the canal-boat captains are women, who own their boats and manage them well. "At Albany a permit must be obtained at the Capitol for taking a pleasure-craft through the canal. There is no difficulty in obtaining this, however, and no charge is made. We are now on our way back, having been through the Champlain Canal, and having spent a few days in Lake Champlain. "The canal begins at West Troy, and the distance to Whitehall, where it enters the lake, is sixty-eight miles. There are twenty-six locks to pass through. The scenery was really very beautiful at times. In Lake Champlain we had some good fishing, taking a number of small bass, pickerel, and perch. We were only sorry that we had so little time to spend there. if our trip could have been a longer one, we could have passed through the Chambly Canal (at the upper end of Lake Champlain) into the Richelieu River and then into the St. Lawrence and on to the Thousand Islands. Next year we hope to go through the Erie Canal to Buffalo, which will give us the scenery of the beautiful Mohawk Valley, and then on as far, perhaps, as Montreal. "We had several very amusing experiences while we were in the canal. One evening we had laid up against the heel-path (the side opposite the tow-path) and the cabin-door had been closed for the night but not locked. 'Rocks' and Henry were asleep, while the captain and I were nearly ready for bed. "Suddenly there was a thud on the deck, the door was flung open, and in burst a thin, wiry, bustling little Yankee. With no more introduction than 'Hello, boys!' and without waiting to say another word, be began a tour of the whole boat, opening every locker, examining critically everything he came across, spelling out the names of the brands of canned goods, and commenting rapidly to himself on what he saw. His examination finished, he looked at the captain, remarked upon the thinness of the latter's legs, and with a 'Well, good-night, boys!' he disappeared in the darkness, and we never saw him again. We had been too utterly astonished during his brief, whirlwind-like visit to do or say anything whatever. We simply stared, motionless, until he had gone. "We are now approaching Troy. The canal runs along an upper level around the side of a hill, giving us a far-extended view over the Mohawk Valley and River, some five hundred feet below, and the Erie Canal stretching off to the west. I shall be sorry when our trip ends in a few days hence. It has been the most enjoyable outing I ever had. I shall probably tire you with my enthusiasm after I return. "Till then, believe me, "Yours, as ever, "J. S. W." The best part of this story of a summer outing is that none of it (except the names and dates) is fictitious. The Satan was built exactly as described, and is now ready for her third summer cruise. What Captain Perkins has accomplished is within the reach also of any other lover of life on the water, at the same modest expenditure and with the same happy results. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

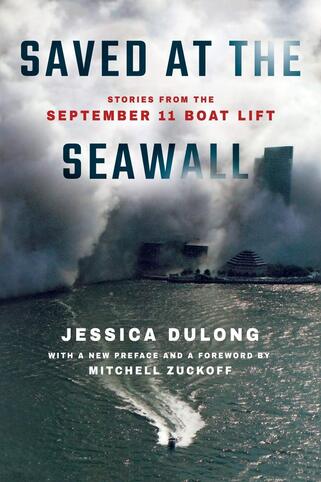

View this fascinating video detailing the history of the Esopus Creek. The history and community of Saugerties, New York, is interpreted through its relationship to the Esopus Creek and Hudson River. Directed by Katie Cokinos and Guy Reed. Original Music: Carl Mateo. Camera and Editorial: Alex Rappoport. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today! When the World Trade Center was attacked on the morning of September 11, 2001 and bridges and airports and trains were shut down, a fact that most people don't think about suddenly became abundantly clear - Manhattan is an island. Maritime tradition has a long history of duty to rescue. Since the Age of Sail, when vessels were on the open ocean for months and weeks at a time, far from land, sailors had to rely on each other in emergency situations. The duty to rescue is now codified in Congressional maritime law. But the community of mariners in and around New York Harbor didn't need a law to tell them what to do. When the U.S. Coast Guard put out the radio call to all vessels to assist with the evacuation of lower Manhattan, hundreds answered. Each year, on the anniversary of the September 11 attacks, we share this short documentary film. "Boatlift," narrated by Tom Hanks, gives a stirring account of the actions of ordinary people that day - Fred Rogers' "helpers" - who made a difference for hundreds of thousands of people. Sadly, like many of those who responded to 9/11, Vincent Ardolino, captain of the Amberjack V, passed away in 2018. But their stories live on.  A new book about the attack has recently been published. Saved at the Seawall Stories from the September 11 Boat Lift by Jessica DuLong (author of My Hudson River Chronicles and engineer-in-training aboard the John J. Harvey that fateful day) pieces together the story of the largest marine evacuation since Dunkirk through eyewitness accounts. DuLong will be speaking for the museum's lecture series in honor of the 20th anniversary. "Heroes or Humans: September 11th Lessons on the 20th Anniversary" will be held virtually on Wednesday, September 22, 2021 at 8:00 PM. The book will also be available for purchase at the museum store. In May of 2022, the Hudson River Maritime Museum will be running a Grain Race in cooperation with the Schooner Apollonia, The Northeast Grainshed Alliance, and the Center for Post Carbon Logistics. Anyone interested in the race can find out more here. The Grain Race Rules state the following: "Over the course of one Month (May for Grain, October for Pumpkins) participants may enter one cargo voyage." This may not be as clear as possible, and so this supplement to the rules is being issued. The One Voyage requirement will be satisfied so long as the cargo involves only one Point of Origin OR Destination. For example, a voyage from a single malt-house to three breweries in the same trip will qualify. Similarly, picking up Grains at more than one farm to deliver to one Producer would qualify as a single voyage. Cargo must be distinguished for each segment when accounting for ton-mile points. For example, a load of 3 tons from one point of origin dropped at three locations with one ton each can only count each ton from the start to its destination. While the first leg will gain 3 ton-miles per mile traveled, the second will only gain two, and so on. The same principle applies for multiple points of origin. What does not qualify as a single voyage is picking up cargo at more than one point and delivering at more than one point. Similarly, Voyages are one direction, not round trips, so return cargoes cannot be counted as part of the same voyage. Fuel accounting is not effected by multiple legs being involved in a voyage. All fuel burned or grid power used on all legs of a voyage must be accounted for. You can find more information on the Grain Race here. AuthorSteven Woods is the Solaris and Education coordinator at HRMM. He earned his Master's degree in Resilient and Sustainable Communities at Prescott College, and wrote his thesis on the revival of Sail Freight for supplying the New York Metro Area's food needs. Steven has worked in Museums for over 20 years. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

|

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 [email protected] Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |