History Blog

|

|

|

|

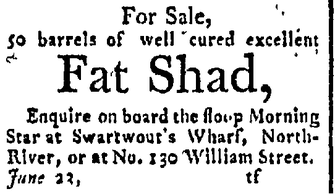

June 26, 1794 newspaper advertisement for barrels of cured shad. From the newspaper American Minerva. June 26, 1794 newspaper advertisement for barrels of cured shad. From the newspaper American Minerva.

By Sarah Wassberg, Director of Education and Allynne Lange, Curator

Much has been made of the American shad. A large, silvery herring, this celebrated fish was once one of the three most often commercially caught fish in the Hudson River. Shad is an anadromous fish, meaning that like salmon it is born in fresh water, lives its adult life in the ocean, and comes back up Atlantic coast rivers to spawn. Unlike salmon, shad do not then die but rather swim back out to sea to live and breed again. Although shad begin their runs up rivers as early as March, April is usually the month in which shad return in significant numbers to the Hudson, their arrival heralded by the blooming of the “shad bush,” also known as the serviceberry or Saskatoon. The shad run generally lasts until the end of May or early June. Shad are a prey fish for many larger fish such as striped bass, as well as food for humans. Ever since humans first lived in the Hudson Valley, the annual spring shad run provided much-needed protein after the long winter. Shad are valued for their tasty flesh, which has almost twice the levels of omega 3s as salmon, as well as for their rich eggs or roe. Although delicious, as a herring shad is very bony, taking eleven cuts to fillet. Traditionally, the female or “roe” shad was much more desirable than the male or “buck” shad due to its eggs and larger size. Roe was either harvested by gently squeezing it out of the female or by gutting the fish and removing the whole egg sack, which was generally lightly battered or floured and fried in bacon fat for an extra-rich dish. Shad roe was historically considered a spring delicacy in the Hudson Valley. Although you can sport fish for shad, they have traditionally been caught with stake nets in the lower Hudson and drift nets in the mid-Hudson and north. The stake nets were long, rectangular nets affixed to long wooden poles in the shallower areas of the Hudson River. Drift nets, also long and rectangular, were cast from the shad boats on a favorable tide. As the tide flowed the fish were caught in the nets which hung vertically like curtains with weights on the bottom edge. Nets must be pulled up and fish removed by hand before the tide changes. If left in the nets too long the shad will die or, as happened to fisherman Edward Hatzmann, eels will go up inside the live roe shad and eat the eggs right out of them. Over the past ten or more years, the yearly shad run has dwindled dramatically, and shad is now considered endangered and may not be caught. Reasons for this change are many, including predator fish like the striped bass, as well as offshore fishing. Whatever the reasons, the shad, once the harbingers of spring, are much missed. Shad boats are specially designed rowboats (later powered by outboard motors) which are wide with a relatively shallow draft. Working two or more men to a boat, one man would row while the other would run out the nets in the morning, and then collect the net a few hours later, generally removing the shad to the bottom of the boat as the nets were pulled in. A special wooden platform at the stern of the boat made it easier to pile the nets and remove the shad. You can see a restored shad boat in the East Gallery of the museum. Port Ewen fisherman George Clark recounts working in all weather. Fishing for shad commercially was hard work. Often fishermen were up as early as 3 or 4 AM and worked one or sometimes both tides. Because shad was a seasonal fish, most fishermen had other jobs. A good shad run meant extra income during a lean time of year, but fishermen in the 20th century rarely made enough money to do much more than break even, especially the larger operations which hired on extra men. George Clark tells of a fish dealer who tries to buy shad from his father for a penny a piece. Historically shad has been an important food fish, especially during times of hardship. During World War II all fishing was banned in New York Harbor. Fisherman Frank Parslow recounts the impact of rationing and the harbor fishing ban on Hudson River fishermen. To learn more about shad fishing from Hudson River fishermen, check out our digitized oral history collection, available onwww.hrvh.org.

2 Comments

|

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 [email protected] Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |