History Blog

|

|

|

|

|

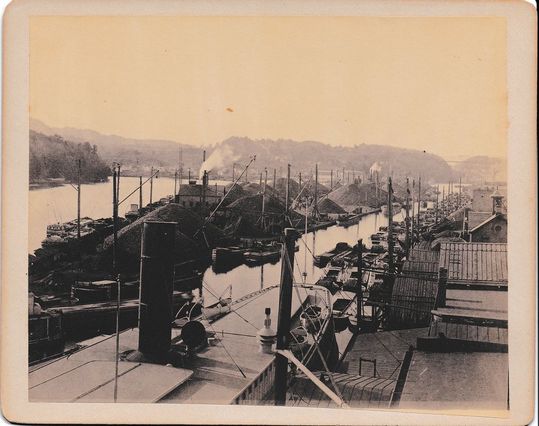

Editor's Note: This article originally appeared in the Hudson River Maritime Museum's 2017 issue of the Pilot Log. The Hudson River was integral to the development of the Delaware and Hudson Canal. The Canal was conceived by Philadelphia dry goods merchants Maurice and Charles Wurts in the second decade of the 19th century, in order to transport anthracite coal from Pennsylvania mines to New York City. The coal traversed the 108-mile-long Canal, winding through the Lackawaxen, Delaware, Neversink, Bashakill, Sandburgh and Rondout valleys before arriving at the Hudson River near Kingston, NY. From there, the cargo would travel south on the Hudson for over eighty miles to supply the primary market in New York City. Coal was also shipped north to Albany—about forty-five miles—and from there it could be transported on the Erie Canal to support the westward expansion of the population.  Island Dock in the Rondout Creek showing coal loader machines made by the Dodge Coal Storage Co. of Philadelphia. The canal boats behind the steamboat have had their rear compartments 'hipped', the addition of higher sidewalls to accommodate a greater load, and appear to possibly rafted together to be towed by the steamboat. D&H Canal Historical Society Collection, #73.22. Benjamin Wright (the chief engineer of the middle section of the Erie Canal) oversaw the original plans for the D&H Canal, which date from 1823. He believed that “the Canal boats may navigate the Hudson. A steam boat of 50 horse power will tow ten of them, and if double manned will perform the trip to New York and back in 2 days, the distance 100 miles.”[1] However, the earliest canal boats, which were 75 feet long and 9 feet wide, with a capacity 30 tons, proved unsuitable for travel on the river. As a result, coal had to be offloaded from canal boats to other vessels at Rondout for transport on the Hudson River—a time-consuming and costly process. In Steamboats for Rondout Donald Ringwald writes, “...the canalboats obviously had to be small size and because of this and a need to keep them on their regular work, they generally did not go beyond the Company works on Rondout Creek.”[2] By 1831, the Company had begun purchasing barges for use on the Hudson. The first two were the Lackawanna (146 feet in length) and the James Kent (135 feet in length), and to tow them, the D&H Canal Company “chartered and then purchased an elderly sidewinder named Delaware.”[3] As the Canal Company prospered, the Canal was enlarged. In the 1840s, the depth was incrementally increased from four to five feet, with no change in the original width of thirty-two feet. In 1847, anticipating increased traffic from a deal with the Wyoming Coal Association (which later became the Pennsylvania Coal Company) to transport their coal on the D&H Canal, the company enlarged the waterway, which reached its final depth of six feet and width of forty to fifty feet by 1850. The new dimensions of the Canal accommodated boats that were ninety-one feet long, fourteen and a half feet wide, and could carry up to 130 tons of coal.[4] Safe navigation of the Hudson was considered so important that, in a letter dated January 21, 1852 from head engineer Russel Farnum Lord to President John Wurts, a discussion of the new boats for the enlarged canal noted: “The Birdsall Lattice Boats derive their advantage of carrying the largest cargoes, mainly, if not entirely, from the difference in their weight when light – Their plan of construction however is such that there is a reason to doubt their durability and substantial ability for use on the river.”[5] Later, referring to boats from a different builder, he wrote: “From the experience had, it is evident that the Round Bow Section Scows are, and will be, the best and most desirable for the Coal Canal business – With them an important and permanent reduction in the rate of freight may be established – The only draw back is, whether they will be competent for the river transportation.”[6] The cost of handling the coal at Rondout was uppermost in their minds and the larger boats that the company ordered proved Hudson River – worthy. Throughout the 19th century and into the 20th, rafts of up to 100 canal scows were frequently encountered on the Hudson. On August 18, 1889 The New York Times wrote: Very few persons who journey up or down the Hudson River either upon the palatial steamers or upon the railway trains that run along both banks of this great waterway know how great an amount of wealth is daily floated to this city on the canalboats and barges that compose the immense tows that daily leave West Troy, Lansingburg, Albany, Kingston, and other points along the river bound for this city…. From Kingston, which is the tide-water outlet of the Delaware and Hudson Canal, another class of merchandise is shipped in the same manner. From the mouth of the Rondout Creek, which forms the harbor of the thriving and busy city of Kingston, can be seen emerging every evening huge rafts of canalboats, tall-masted down-Easters, and barges of various sorts, laden with coal, ice, hay, lumber, lime, cement, bluestone, brick, and country produce. Many of these craft have received their cargoes at the wharves of Kingston, while others have come from the coal regions about Honesdale and Scranton, in Pennsylvania, all bound for this port and consigned to, perhaps, as many different persons as there are boats in the tow.”[7] From its opening in 1828 through the closing of most of the canal in 1898—and even through 1917, when the section from Rosendale to Rondout finally stopped carrying cement—the Delaware and Hudson Canal was responsible for vast amounts of traffic on the Hudson River. Indeed there would not have been a Delaware and Hudson Canal without the Hudson River! Notes: [1] H. Hollister M.D., History of the Delaware and Hudson Canal Company. Unpublished MS c1880. p. 22. [2] Donald C. Ringwald, Steamboats For Rondout, Passenger Service Between New York and Rondout Creek, 1829 Through 1863. Steamship Historical Society of America, Inc. 1981. p. 17. [3] Ibid. [4] Larry Lowenthal, From the Coalfields to the Hudson. Purple Mountain Press. 1997. pp. 142-48. [5] The letters of Russell F. Lord, chief engineer of the Delaware and Hudson Canal Company, June 1848 to October 1852. D&H Canal Historical Society collection #2016.01.01. Transcribed by Audrey M. Klinkenberg. [6] Ibid. [7] New York Times, August 18, 1889. AuthorBill Merchant is the historian and curator of the D&H Canal Historical Society in High Falls, NY. He lives in a canal side, canal era house in High Falls with his wife Kelly where he also works as a double bass luthier and antique dealer.

0 Comments

Editor's Note: The following text is a verbatim transcription of an article written by George W. Murdock, for the Kingston (NY) Daily Freeman newspaper in the 1930s. Murdock, a veteran marine engineer, wrote a regular column. Articles transcribed by HRMM volunteer Adam Kaplan. For more of Murdock's articles, see the "Steamboat Biographies" category at right No. 11- ALIDA The “Alida,” 265 feet in length, was built as a dayboat for the Hudson river traffic, and commenced her regular trips on April 16, 1847 between New York and Albany. During her career as a passenger carrier, she was always a favorite with the traveling public. The speed of the “Alida” was over 20 miles an hour, and her best time between the two termini of her regular route was made on May 6, 1848, when a trip including seven landings was made in eight hours and 18 minutes. She continued in service on the Albany route for a few years and then was put on regular schedule from Rondout to New York, making a round trip each day. Eventually she was again placed on the entire run between Albany and New York. In November, 1855, Alfred Van Santvoord purchased the “Alida,” and the following season he ran her the entire distance of the river with the steamboat “Armenia” as a consort. The new owner, better known as Commodore Van Santvoord had long been identified with river freight and towing business but had not been previously interested in the passenger carrying line. The “Alida” was his first venture into this department of river travel. Later, in the year 1860, he launched the “Daniel Drew,” and then began to use the “Alida” as a passenger boat between Poughkeepsie and New York, making a round trip daily. This venture into the passenger carrying business must have appeared to the Commodore as being quite successful, because in the year 1863, he associated himself with several other rivermen, added the “Armenia” to his fleet which now numbered three boats- the “Alida,” “Daniel Drew” and the "Armenia"- and so laid the foundations of the Albany Dayline which is now known as the Hudson River Dayline. The “Alida” was eventually converted into a towboat, and in the late sixties, when the Commodore vacated his position in the towing business, he sold the “Alida” to Robinson & Betts Towing Company of Troy. The converted towboat operated for this firm between Troy and New York until 1874 when the firm itself ceased operation, and the “Alida” was purchased by Thomas Cornell of Rondout in the winter of 1875. The “Alida” only made one trip for the Cornell line, that in December of 1875. On the first of that month, the passenger boat “Sunnyside” was sunk at West Park, and it was decided to use the engine of the “Alida” in a new boat. The “Alida” was towed to New York by the “Norwich,” but her engine was found to be too small for the designed boat so she was hauled back to Port Ewen and laid up there until the summer of 1880 when she was bought by Daniel Bigler and broken up off Port Ewen. [Editor's Note: The tow cabin from the "Alida" is on the campus of the Hudson River Maritime Museum.] AuthorGeorge W. Murdock, (b. 1853-d. 1940) was a veteran marine engineer who served on the steamboats "Utica", "Sunnyside", "City of Troy", and "Mary Powell". He also helped dismantle engines in scrapped steamboats in the winter months and later in his career worked as an engineer at the brickyards in Port Ewen. In 1883 he moved to Brooklyn, NY and operated several private yachts. He ended his career working in power houses in the outer boroughs of New York City. His mother Catherine Murdock was the keeper of the Rondout Lighthouse for 50 years. |

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 [email protected] Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |