History Blog

|

|

|

|

|

Today's featured artifact is a unique one. The museum has several of these tin foghorns in its collection, but this is one of the only ones with a name attached! This dark green tin foghorn belonged to the William S. Earl, often abbreviated to Wm. S. Earl, a Cornell Steamboat Company tugboat in operation on the Rondout from 1884 until 1947. Built in 1859 in Philadelphia, PA, she was seriously damaged by fire on three separate occasions - on December 1, 1881 in Greenbush, NY; on December 13, 1903 at Rondout, and on May 30, 1936 also at Rondout. Each time she was rebuilt and continued to operate. One of the oldest propeller tugs in the Cornell fleet, she was beaten in age only by the Terror, an aptly named tugboat built in 1854, purchased by Cornell in 1892, and condemned by steamboat inspectors as unsafe in 1910. The Wm. S. Earl was finally abandoned July 20, 1949 and scuttled in Port Ewen, NY at 90 years old. Her long life and frequent rehabilitation was attributed Edward Coykendall (grandson of Thomas Cornell), who considered the Wm. S. Earl a favorite. The foghorn itself appears designed to be blown by the mouth and the sound likely would not have traveled very far, but it would have been enough to notify other boats of the Wm. S. Earl's presence in a fog. Essentially, foghorns like this helped prevent boats from hitting each other! The Smithsonian National Museum of American History also has several tin foghorns, including this one, which was used on fishing dories off the Grand Banks in the 1880s. To learn more about the history of fog signals, check out this detailed article from the United States Lighthouse Society. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

0 Comments

Editor's Note: The following text is a verbatim transcription of an article written by George W. Murdock, for the Kingston (NY) Daily Freeman newspaper in the 1930s. Murdock, a veteran marine engineer, wrote a regular column. Articles transcribed by HRMM volunteer Adam Kaplan. The “Ansonia” was built for the New York-Derby, Conn., route in the year 1848, with George Deming, captain, Frederick Perkins, pilot, and John M. White, chief engineer. She was 190 feet long with a 28 foot beam, and ran on Long Island Sound on the Derby route until 1860, when she was purchased by Brett & Matthews of Fishkill Landing, refitted and renamed the “William Kent.” Under the name of the “William Kent,” this steamboat sailed the Hudson between Fishkill Landing and New York until 1861, when she was chartered by the government for the transportation of troops for the sum of $700 per day. She was employed by the federal government for a period of 77 days and was then discharged from service. About this time the government passed a law which said that unless a steamboat was entirely rebuilt, her name could not be changed. The purpose of the law was to protect the public who might think they were traveling on a new boat when in reality the only thing new would be the name. This law necessitated the name “Ansonia” being again emblazoned on the sides of the “William Kent,” and so under the original name of the “Ansonia” she plied the Delaware river between Philadelphia and Cape May in the year 1862. Following this sojourn at the Quaker City, the “Ansonia” was brought back to New York and placed in service on her former route between Fishkill Landing and the metropolis as a freight and passenger carrier under Captain J.T. Brett. Following this she was sold to the Saugerties Steamboat Company and began regular trips between Saugerties and New York. In the winter of 1892 the Ansonia was rebuilt at South Brooklyn, being lengthened to 205 feet, and her name was changed to the “Ulster,” with a tonnage rating of 780 gross tons or 580 net tons. On November 11, 1897, the “Ulster” ran on the rocks at Butter Hill, just below Cornwall-on-Hudson about midnight and rested there with her stern submerged in the water and her bow on the rocks. She slipped off the rocks and sunk in 30 feet of water. At the time of the accident she was heavily loaded with freight and carried 105 passengers, all of whom were safely landed on shore. A further account of this disaster tells of the “Ulster” leaving New York about seven o’clock in the evening on an exceedingly stormy night. When she reached Haverstraw Bay, a wind storm arose and blew down the river at a rate of about 30 miles an hour. The pilot hugged the west shore of the river so as not to face the full force of the gale. The river was very rough and when opposite Butter Hill, the “Ulster” was blown on the rocky shore and a hole stove in her hull. Most of the passengers were in their berths at the time but they were quickly aroused and gotten off with a minimum of confusion. The “Ulster” was raised and rebuilt and placed in service on her regular route, running until the fall of 1921, when she was taken up to Rondout creek to Hiltebrant’s shipyard and was there rebuilt in the winter of 1922. The Vulcan Iron Works of Jersey City constructed a new boiler for the steamer and her name was changed to the “Robert A. Snyder” in honor of the late Robert A. Snyder who was for many years the president and superintendent of the Saugerties and New York Steamboat Company. She ran on the Saugerties line in conjunction with the steamboat “Ida." On Friday, February 20, 1936, the “Robert A. Snyder” was crushed by the ice as she lay in the lower creek off Saugerties where she had been tied up with her sister ship, the “Ida”, since the Saugerties Line ceased operation some four years before. The water was shallow at that point and the remains of the once famous boat now lies rotting to pieces on the muddy bottom of the Saugerties Creek, a sight that will bring back many memories of the olden days on the Hudson river to any of the old boatmen who were active at the time when the “Robert A. Snyder” was running on her regular schedule. AuthorGeorge W. Murdock, (b. 1853-d. 1940) was a veteran marine engineer who served on the steamboats "Utica", "Sunnyside", "City of Troy", and "Mary Powell". He also helped dismantle engines in scrapped steamboats in the winter months and later in his career worked as an engineer at the brickyards in Port Ewen. In 1883 he moved to Brooklyn, NY and operated several private yachts. He ended his career working in power houses in the outer boroughs of New York City. His mother Catherine Murdock was the keeper of the Rondout Lighthouse for 50 years. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor’s Note: The following text is a verbatim transcription of an article featuring stories by Captain William O. Benson (1911-1986). Beginning in 1971, Benson, a retired tugboat captain, reminisced about his 40 years on the Hudson River in a regular column for the Kingston (NY) Freeman’s Sunday Tempo magazine. Captain Benson's articles were compiled and transcribed by HRMM volunteer Carl Mayer. See more of Captain Benson’s articles here. This article was originally published October 14, 1972. For a period of over 70 years prior to 1928, there was a steamboat service between Newburgh and Albany. At its peak there was a steamboat in each direction, carrying freight and passengers on a daily basis. The steamers would make landings at almost every city, village and hamlet along the banks of the upper river. During the latter part of the 19th century and the first part of the 20th century, the steamboats “Jacob H. Tremper” and “M. Martin” were the two steamboats providing the service. At the end of the 1918 season, the “Martin” had outlived her usefulness and for the next ten years the “Tremper’” carried on alone, going up one day and returning the next. As the 1920’s wore on, business on the line continued to dwindle. The “Tremper” stopped carrying passengers and in her final years was used to carry freight only. After over 40 years of service, the “Tremper" really showed her age. Her guards hung low above the water and eel grass would hang from her paddle boxes. One morning in the late summer of her final season, the steamer “Trojan” of the Hudson River Night Line was landing at Albany just as the “Jacob H. Tremper” paddled by one her down river trip. Three lady passengers were out on the upper deck watching her go by. As Captain George Warner of the “Trojan” came down from the bridge, one of the lady passengers said to him, “My goodness Captain, what old boat is that?” The Captain replied, “Why my good ladies, did you ever hear of the ‘Half Moon’?” "Yes,” said the lady, “Henry Hudson discovered this river with the ‘Half Moon’.” “Well,” the Captain said, “That is the other half of the ‘Half Moon’.” During the mid-1920’s when I was a teenage boy growing up in Sleightsburgh, it used to be quite a sight to see the old “Jacob H. Tremper” coming in Rondout Creek about 10:30 a.m. on her up trip and then about 3 or 4 p.m. the next day on her down trip. Her guards would nearly be dragging in the water, her forward deck would be loaded with freight, and water would be pouring out of the lattice work on her wheel houses. When it would be flood tide, she would come very close to Sleight’s dock at Sleightsburgh so as to turn and put her port bow to the dock, under the stern of the “Benjamin B. Odell” or “Homer Ramsdell,” at Rondout. At that time, Sleight’s store was still in operation adjacent to the old chain ferry slip. When the “Tremper” would pass close to the dock, some of the Sleightsburgh boys would get overripe tomatoes or rotten eggs from Sleight’s store and see how many letters in the name on her paddle box they could hit. Although I am somewhat reluctant to admit it now, I was one of them. How the mate would shake his fist and swear at us! Since the “Tremper” no longer carried passengers, her deck crew no longer bothered to scrub the white work. The splotches from the eggs and tomatoes would be on all summer and fall. She sure did look like a “Half Moon.” As a boy, it never occurred to me the “Tremper” was nearing the end of her career. In the eyes of a barefoot youth, time stood still and somehow it seemed summer would last forever. Then, it seemed impossible that in but a few short years the “Jacob H. Tremper” would no longer be coming in Rondout Creek, black soft coal smoke trailing from her tall, black smokestack, a white plume of steam rising skyward from her whistle as she blew off the Cornell coal pocket for the deckhands to get ready to handle her lines. AuthorCaptain William Odell Benson was a life-long resident of Sleightsburgh, N.Y., where he was born on March 17, 1911, the son of the late Albert and Ida Olson Benson. He served as captain of Callanan Company tugs including Peter Callanan, and Callanan No. 1 and was an early member of the Hudson River Maritime Museum. He retained, and shared, lifelong memories of incidents and anecdotes along the Hudson River. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Today's Media Monday post is this wonderful film from 1938 about the construction of the Lincoln Tunnel! First proposed in the 1920s as the "Midtown Hudson Tunnel," construction on the tunnel began in 1934, connecting Weekhawken, NJ and midtown Manhattan. The first tube opened in 1937, just a year before this film was produced. The Port Authority advertised the tunnel as "The Direct Way to Times Square" and in the first 24 hours over 7,500 vehicles used the tunnel, which officially opened December 22, 1937, just in time for the busy holiday season. Bus companies were especially happy to be allowed to use the tunnel - previously they had had to board ferries in Weehawken bound for New York City. Two more tubes were later added due to traffic increases, opening in 1945 and 1957, respectively. Construction of the second tube began almost immediately, as the equipment and personnel were already on site. Automobile tunnels under the Hudson River helped alleviate some of the congestion of bridges and ferries, changing New York City streets forever. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's Note: The following text is a verbatim transcription of an article written by George W. Murdock, for the Kingston (NY) Daily Freeman newspaper in the 1930s. Murdock, a veteran marine engineer, wrote a regular column. Articles transcribed by HRMM volunteer Adam Kaplan. The tale of the steamboat “Sarah E. Brown,” known for a period in her existence as the “fish market boat,” begins in 1860, travels through the Civil War and comes to the Rondout creek harbor, and finally ends as the wreckers tear apart the remains of the vessel which lost a battle with the ice in the creek and was wrecked beyond repair, in the year 1893. The wooden hull of the “Sarah E. Brown” was built at Brooklyn in 1860. She was 91 feet long, breadth of beam 19 feet five inches, depth of hold five feet eight inches. Her gross tonnage was listed at 45, with a net tonnage of 22, and she was propelled by a vertical beam engine with a cylinder diameter of 24 inches with a six foot stroke. As can be ascertained from the above dimensions, the “Sarah E. Brown” was a small side wheel steamboat, which was built for towing service in and around New York harbor. There were many vessels similar to the “Sarah E. Brown” in use for the same purpose at that period in steamboat history. Shortly after the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, the “Sarah E. Brown” was taken over by the war department and placed in service on the Potomac river, being used principally in places where the river was too shallow for the larger vessels to navigate safely. In 1865, at the close of the war, the “Sarah E. Brown” was brought north to the Brooklyn Navy Yard and tied up, and the following year she was sold to Thomas Cornell along with another side wheel steamboat, the “Ceres.” These two vessels, both painted black according to the practice of the federal government during the war, arrived at Rondout and were used for towing purposes in and around the Rondout creek. Under the command of Captain Sandy Forsythe, the “Sarah E. Brown,” with Peter Powell as chief engineer, became a familiar sight along the river in the vicinity of the mouth of the Rondout creek. The year 1869 marks the event which brought the nickname of the “fish market boat” to the “Sarah E. Brown.” A collision with an ice barge stove in the wheelhouse of the “Sarah E. Brown” carrying away much of the woodwork and leaving only the letters S.E.B. of her full name. Immediately some wag along the docks found the three letters could be the initial letters to the words “suckers,” “eels” and “bullheads,” and so the “Sarah E. Brown” came into the name of the “fish market boat.” During the winter of 1870 the “Sarah E. Brown” was rebuilt at Sleightsburgh by Morgan Everyone, and Major Cornell was asked what name he wished for the rebuilt craft. It is reported that Major Cornell in turn asked Captain Sandy Forsythe what name he thought would be appropriate, and the captain replied that the name “Sandy” would do. Thus the “Sarah E. Brown” became the towboat “Sandy.” The “Sandy” was in use around the Rondout harbor until the fall of 1892, and then it was an accident which occurred during the period when she was tied up for the winter, that brought the career of the “Sandy” to a close. N March 13, 1893, the ice in the upper section of the Rondout creek broke loose due to a spring freshet, and thousands off tons of ice rode the raging torrent down the creek. The onslaught of this mass swept many of the tied-up vessels from their moorings, and the side of the “Sandy” was crushed, causing the wrecked steamboat to sink. She was raised but was found to be in such condition that she was no longer of any use, and she was sold to Jacob Herold and broken up at Rondout. AuthorGeorge W. Murdock, (b. 1853-d. 1940) was a veteran marine engineer who served on the steamboats "Utica", "Sunnyside", "City of Troy", and "Mary Powell". He also helped dismantle engines in scrapped steamboats in the winter months and later in his career worked as an engineer at the brickyards in Port Ewen. In 1883 he moved to Brooklyn, NY and operated several private yachts. He ended his career working in power houses in the outer boroughs of New York City. His mother Catherine Murdock was the keeper of the Rondout Lighthouse for 50 years. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor’s Note: The following text is a verbatim transcription of an article featuring stories by Captain William O. Benson (1911-1986). Beginning in 1971, Benson, a retired tugboat captain, reminisced about his 40 years on the Hudson River in a regular column for the Kingston (NY) Freeman’s Sunday Tempo magazine. Captain Benson's articles were compiled and transcribed by HRMM volunteer Carl Mayer. See more of Captain Benson’s articles here. This article was originally published October 13, 1974. Ever since the rumble of summer thunder in the Catskills was attributed by Washington Irving to a form of bowling by his merry little men, the Hudson Valley has had a certain renown for its thunder and lightning storms. Many a boatman has been a witness to spectacular lightning displays, primarily because his boat has been in the middle of the river and he had, as a result, a particularly good vantage point. There have been a number of instances where river boats have even been struck by lightning, although I don’t know of a single instance where a boat has been seriously damaged as a result. This has probably been due, I suppose, to the fact the boat has been effectively grounded by the water on which it floated. When boats have been struck by lightning, almost always the target for the lightning bolt has been the flag poles. In some instances, a flag pole has been split right down the middle. In others, a flag pole has been snapped off like a matchstick. Events, such as I describe, I know have occurred to the Day Liners “Alexander Hamilton," "Hendrick Hudson" and “Albany.” Since the beginning of steamboating, steamers have always carried flagpoles and generally, a generous display of flags and bunting. If nothing else, the flags gaily flapping in the breeze helped attract attention to the steamer. Even at night or in the dreariest weather, one would always find a pennant or a wind sock flying from the forward flag pole, for this would help tell the pilot from which direction the wind was blowing. The Day Liners, in particular, always had a lot of flag poles. The big sidewheelers carried eleven flag poles — one at the bow from which on a good day would fly the union jack, one in back of the pilot house from which would fly the house flag, one at the stern from which would fly the national ensign, and eight side poles from which would fly smaller American flags. During their profit making years, a Day Liner would start the season with a complete set of new flags for sunny days, a complete set of older flags for rainy days, and a set of pennants for windy days. Prior to World War I, the side poles used to fly the flags of foreign countries, allegedly as a tribute to the diverse population of New York City and its reputation as the nation’s “melting pot," not to mention the possibility of perhaps attracting the people of these diverse backgrounds to ride the steamers. When lightning would strike a steamer’s flag pole, the jack staff - the one at the bow - seemed to be the greatest attraction. One one occasion in the 1930's, the “Alexander Hamilton” was in the lower river when she ran into a severe thunderstorm. The passengers scurried for cover. Shortly thereafter a bolt of lightning struck the jack staff, snapping it off. The pilot later related a ball of fire appeared to roll down the edge of the deck from the broken jack staff to about opposite the pilot house and then roll overboard, with no visible damage other than the broken bow flag pole. The "Hendrick Hudson” had a similar experience but without the accompanying fire-ball. The lightning bolt that struck the "Albany” did so in August 1926 while she lay along the Day Line pier at the foot of 42nd Street, New York during a heavy thunder shower. The lightning in this case struck the stern flag pole and split it down the middle so it lay open like a large palm. In both cases there was no other damage whatever. Perhaps the most spectacular damage from a thunderstorm to a river steamer occurred on June 20, 1899 to the well-known “Mary Powell.” Here, however, the damage was caused by tornado like winds accompanying the storm and not by lightning. Captain A. E. Anderson at the time said it was the worst storm he had encountered in his then 25 years of steamboating. The “Powell” was on her regular up trip from New York to Rondout. Going through Haverstraw Bay, there appeared to be two thunderstorms, one to the southwest and one to the north, both accompanied by generous displays of lightning. Near Stony Point the two storms appeared to meet with the “Mary Powell” right at the center. A cyclonic funnel of dust laden wind seemed to move out from the west shore straight toward the graceful steamboat. The wind caught the "Mary Powell” with great force and listed her sharply to starboard. The starboard smoke stack came crashing down toward the bow onto the paddle box, the stack’s guys snapped and the supporting rods twisted. A very short time later, the port smoke stack also toppled over athwart in this instance the aptly named hurricane deck. The resulting shower of sparks was doused by a deluge of rain that accompanied the storm. In about 15 minutes the storm abated and it was all over. In addition to the toppled smoke stacks, a sliding door had been blown in, the life boats had been lifted from their chocks and the davits bent, and quite a number of folding chairs had been blown overboard. The “Powell's” engineers started her blowers and the steamer continued on her way, making her regular landings at Cranston’s (later Highland Falls), West Point, Cornwall, Newburgh, New Hamburg, Milton, Poughkeepsie, Hyde Park and Rondout. At the time of the great storm, the "Mary Powell” had aboard approximately 200 passengers. Fortunately, none were injured although many were probably shaken by their experience. The “Mary Powell” must have presented a strange appearance as she steamed into Rondout Creek with her fallen smoke stacks. Repair crews had been alerted and as soon as she docked, the workmen commenced work. A gang of men worked throughout the night and it is said the steamer left Kingston the following morning for New York on her regular schedule. AuthorCaptain William Odell Benson was a life-long resident of Sleightsburgh, N.Y., where he was born on March 17, 1911, the son of the late Albert and Ida Olson Benson. He served as captain of Callanan Company tugs including Peter Callanan, and Callanan No. 1 and was an early member of the Hudson River Maritime Museum. He retained, and shared, lifelong memories of incidents and anecdotes along the Hudson River. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Perhaps you've taken a Metro North or Amtrak train to or from New York City and seen this ruined castle on the Hudson. Or maybe you've seen it from scenic route 218 along the face of Storm King Mountain. Or maybe you've seen it from the shores of Newburgh, NY. Either way, Pollopel Island has been host to this curious structure since the early 1900s. To learn more about Bannerman's Castle, check out the video below! Want to visit Bannerman's Castle? You can! The island and castle are managed by the Bannerman's Castle Trust, a non-profit friends group working hand-in-hand with New York State Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation to preserve, stabilize, and provide access to the castle. To book a program or support the Trust, visit their website at bannermancastle.org. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

In 1917 the steamboat Mary Powell took one of her last excursions. The above advertisement, published in June, 1917, gives Hudson Valley residents the opportunity to travel down to New York City to see Billy Sunday's Tabernacle.

Sunday was a former baseball star turned evangelical Christian and had been known for his fiery revivals. But although he once said Prohibition was a greater cause than the First World War, when the U.S. entered the war in April of 1917, he turned to his pulpit to decry Germany and Kaiser Wilhelm as tools of the Devil.

He arrived in New York City to enormous crowds just days after the U.S. entrance into the war. Thousands met him at Penn Station, where he required a police escort. Thousands more thronged into his custom-built Tabernacle where he preached fiery revivals with a patriotic tinge. The tabernacle included 16,000 seats. He gave revivals multiple times a week in New York City for over ten weeks.

Without amplification, Sunday used enormous gestures, a gregarious personality, and special acoustics along with music to make his points.

While in New York City in 1917, Sunday purportedly converted nearly 100,000 people to his brand of Christianity and was in the pages of the New York Times constantly during the ten weeks of the revival.

But like the Mary Powell, Billy Sunday's career waned after 1917, especially after the end of the First World War and the onset of Prohibition - his cause celebre - in 1920. He continued to preach the revival circuit, albeit to smaller and smaller crowds, until his death in 1935. The Mary Powell's 1917 season was her last. She was out of service in 1918, sidelined due to coal shortages thanks to the First World War, and sold in 1919 for scrap.

To learn more about the Mary Powell and her long career, visit our online exhibit, "Mary Powell: Queen of the Hudson."

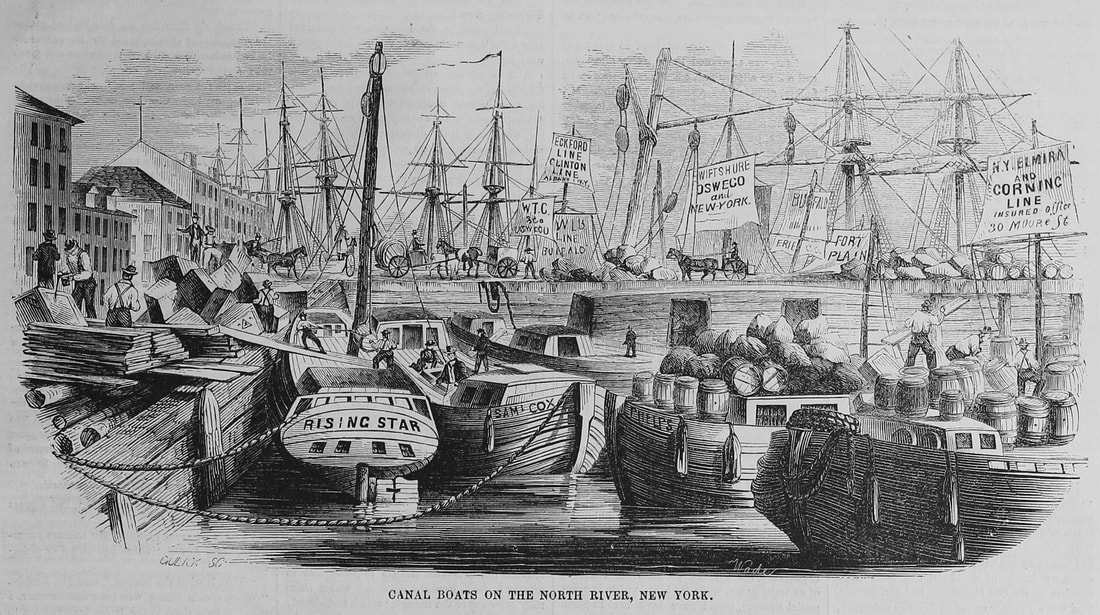

If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today! Editor's note: the following engraving and text were originally published in Gleason's Pictorial Drawing Room Companion, December 25, 1852. Thanks to volunteer researcher George A. Thompson for finding and cataloging this article. The article was transcribed by Sarah Wassberg Johnson, and includes paragraph breaks and bullets not present in the original, to make it easier to read for modern audiences.  "Canal Boats on the North River, New York" by Wade, "Gleason's Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion," December 25, 1852. Note the sail-like signs for various towing lines and destinations, as well as the jumble of lumber and cargo boxes on the pier at left, waiting to be loaded onto the canal boats (or vice versa). Next to the immense foreign export and import trade, comes the inland trade. The whole of the western country from Lake Superior finds a depot at New York. The larger quantity of produce finds its way to the Erie Canal, from thence to the Hudson River to New York. The canal boats run from New York to Buffalo, and vice versa. These boats are made very strong, being bound round by extra guards, to protect them from the many thumps they are subject to. They are towed from Albany to New York - from ten to twenty - by a steamboat, loaded with all the luxuries of the West. The view represented above is taken from Pier No. 1, East River, giving a slight idea of the immense trade which, next to foreign trade, sets New York alive with action. We subjoin from a late census a schedule of the trade; the depot of which, and the modus operandi, Mr. Wade, our artist, has represented in the engraving above, is so truthful and lifelike a manner. In 1840, there were

If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor’s Note: The following text is a verbatim transcription of an article featuring stories by Captain William O. Benson (1911-1986). Beginning in 1971, Benson, a retired tugboat captain, reminisced about his 40 years on the Hudson River in a regular column for the Kingston (NY) Freeman’s Sunday Tempo magazine. Captain Benson's articles were compiled and transcribed by HRMM volunteer Carl Mayer. See more of Captain Benson’s articles here. This article was originally published May 11, 1975. Sooner or later almost every boatman finds himself involved in the intricacies of maritime law, the courts and the questioning of lawyers. Generally the reason is a fog caused grounding, a collision, or some leaky old scow or barge that should have been retired from service many years earlier. Before the days of radar and years ago when New York harbor was much more crowded than it is today, it seemed the boatman’s days in court were more frequent. Court appearances could be unnerving to a boatman since this was not his bag of tricks. In some instances, however, a boatman could hold his own. Two instances come to mind. One such instance took place around 1921 and involved a deckhand on one of the tugboats of the Cornell Steamboat Company. The man was then about 40 years of age and had been a deckhand all his working life, at that time not having advanced to a pilot or captain. He was testifying in a lawsuit involving a collision between two tugs, each towing some scows. The deckhand was on the witness stand being questioned by the lawyer for the opposition. The lawyer was about the same age as the deckhand and during the questioning, apparently was not getting the answers he desired. It would appear the lawyer then decided to try another tack and attempted to discredit the competency of the witness. The lawyer started by asking the deckhand how long he had worked on tugboats, his age, all in a rather derogatory manner. Finally, the lawyer said, “You have been working on boats for over 20 years and you are still a deckhand?” The decky answered, “Yes Sir,” to which the lawyer shook his head and sort of snickered. With that, the deckhand turned to the judge and said, “Your Honor, could I please ask this man a question?” The judge, perhaps being a student of human nature, replied. “You may.” The deckhand then turned and said, “Mr. Lawyer, how long have you been practicing law?” The lawyer sort of threw out his chest and replied, “Since I was 23 years of age.” With that, the deckhand turned his palm upward towards the judge, and said, “Then why aren’t you on the bench like this man?” They say the judge just put his head down on his arms on his desk and shook with laughter — as did the whole courtroom. It may or may not have had anything to do with the deckhand's questions, but it is said the case was thrown out of court. The other instance could be called “The Case of the Wrong Log Book.” As I guess everyone is aware, every vessel keeps a log book of events as they happen, weather changes, etc. It is kept in the pilot house by the pilot on watch. On this occasion, many years ago, the Cornell Steamboat Company owned a tugboat named the “Eli B. Conine." She was involved in a collision in New York harbor with, I believe, a Delaware and Lackawanna Railroad tugboat towing a car float. There was quite a bit of damage to the port stern, railing and cabin of the “Conine." As time went on, the case came up on the court calendar. The lawyer for the railroad was a very highly dressed, very dignified person to look at. One would think from his looks he should be on the Supreme Court. The “Conine's" pilot, who had been on watch at the time of the accident was on the witness stand. All the regular questions were asked by the railroad’s lawyer. As the questioning went on, the lawyer was getting a little impatient with the pilot and his answers, as it seemed the pilot just could not recall, he forgot, etc. Finally, the lawyer literally grabbed one of two log books that had been impounded by the court, and said, “Is this your tug’s log book?” The pilot answered, “Yes Sir." Said the lawyer, “Is this your writing?” Answered the pilot, “Yes Sir." Queried the lawyer, “Did you make a report in your log book about this collision?” to which the pilot again replied, "Yes Sir." By this time the lawyer was raising his voice very high and, in an almost shrill command, ordered, "Well then show it to me.” The pilot started to leaf through the log book of a couple of hundred pages, taking his time, almost as if he were reading each entry and savoring his written word. The lawyer continued to fidget and grow ever more impatient and, in apparent exasperation, turned to the judge and said, "There, he can't even find it himself.” The judge, frowning on the pilot, said, "Are you not supposed to keep all events involving your tugboat recorded in your log?’’ The pilot said, "Yes, Your Honor, we do." “But," the judge said, “it seems this collision was not recorded. Why is that?" The pilot, keeping his face as sober as the judge’s and knowing he was getting the best of the railroad lawyer, replied, "Your Honor, this is the wrong log book.’’ The court, for a moment at least, was in disarray. It seems the collision took place just as one log book had been filled and a new one was being started. The events surrounding the collision were entered in the new book. Both log books had been brought into court, but the lawyer, in his exasperated state, had picked the wrong one to pin down the wily pilot.  In 1926 the "Eli B. Conine" had her steam engine and boiler removed, a diesel engine installed and her name changed to "Cornell No. 41." As a diesel tugboat, she remained in service until the old Cornell Steamboat Company went out of existence in 1958. "Cornell No. 41" is pictured here tied up at the Cornell Steamboat Company docks. Hudson River Maritime Museum Collection. AuthorCaptain William Odell Benson was a life-long resident of Sleightsburgh, N.Y., where he was born on March 17, 1911, the son of the late Albert and Ida Olson Benson. He served as captain of Callanan Company tugs including Peter Callanan, and Callanan No. 1 and was an early member of the Hudson River Maritime Museum. He retained, and shared, lifelong memories of incidents and anecdotes along the Hudson River. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

|

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 [email protected] Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |