History Blog

|

|

|

|

|

In May of 2022, the Hudson River Maritime Museum will be running a Grain Race in cooperation with the Schooner Apollonia, The Northeast Grainshed Alliance, and the Center for Post Carbon Logistics. Anyone interested in the race can find out more here. Grains, as we've seen, were historically and are today a very important agricultural commodity, transported around the world. The 18th century is an especially important time for Grain Shipments in the Northeast, as the current 8-state region in which this competition will take place was producing a large amount of grain exported all around the Atlantic World. New York sent large amounts of Flour and grains to the West Indies, alongside fish, vegetables, timber, and fruits. As the West Indies were essentially a monocrop sugar plantation run entirely with enslaved labor, they needed to import everything from elsewhere. Corn, wheat, and other grains were also sent to the Carolinas from New York, as explained in Peter Kalm's "Travels in North America." Additional grain trade to Europe took place from New York harbor. New England also sent large amounts of grains as exports, though less wheat as conditions were not as favorable for growing it as they were in the Mid-Atlantic colonies. However, grain was shipped from New York and New Jersey into the New England colonies and States, while Fish remained a major regional export. Coastal trading in farm surpluses did include a significant quantity of corn and flour moving into cities such as Boston and being sold there. In Charlestown, NH, the record books of Phineas Stevens' store in the 1740s and 1750s show many debts being paid off in Corn, which Stevens then shipped South into Massachusetts and Connecticut for sale in more densely populated areas. It was moved normally by Canoe down the Connecticut River, then by wagon from the river to a warehouse. The easy cultivation and transportability of grains, alongside their market value in cities made them a good cash crop where few others were available. Aside from the scattered records of individual ships, companies, and ports, there is little to trace direct shipments and the volume of trade in grains, but it was certainly considerable. In many ways, it was Fish, Flour, Rum, and Timber which pervaded the export economy of the Northeast, and were sold to the entire Atlantic World. Domestically, a large amount of grain cargo was moved, whether by pack animals, carts, canoes, or ships. These exports then paid for manufactured goods such as glass, lead, paint, tea, coffee, paper, and others. Taxes on many of these imported goods would lead to grievances over the long term, which eventually spiraled into the American Revolution. Grain in the 18th century was a very important commodity and remains so today. Then as now, the ability to export grain or the need to import it is a tool of foreign policy at peace and in war. While the Northeastern Economy is no longer based primarily on fishing and grains, there is a long tradition of producing and moving grains in the region on which we can draw as we move towards a carbon-constrained future. You can find more information on the Grain Race here. AuthorSteven Woods is the Solaris and Education coordinator at HRMM. He earned his Master's degree in Resilient and Sustainable Communities at Prescott College, and wrote his thesis on the revival of Sail Freight for supplying the New York Metro Area's food needs. Steven has worked in Museums for over 20 years. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

0 Comments

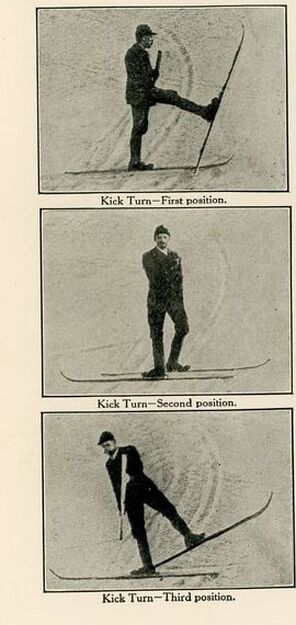

Editor's Note: The following is a verbatim transcription of a chapter from Spalding's Winter Sports by James A. Cruikshank, published in 1917 and part of the Ray Ruge Collection at the Hudson River Maritime Museum. Many thanks to volunteer Adam Kaplan for transcribing this booklet. That the spelling "skiis" is original to the text. There seems to be no doubt that the ski originated in Norway. But it is now to be found everywhere snow falls, from the extreme limits of Greenland to the summits of the Andes where South American Governments employ expert ski runners to carry mail. First as an implement of communication between nations otherwise snow bound, and now as the chosen toy of winter loving thousands it has finally come into its own. Probably no one plaything has so rapidly forged into a leading place among the sport tools of the northern races as these long and curious “planks,” as the Austrians call them. Ten years ago the ski was an interesting ethnological souvenir found only in museums; today it is hard to supply the demand for them. With that imitative and inventive skill characteristic of the Yankee, some of the best skis are now produced in the United States. They have improvements and changes peculiarly adapting them to the climate and the snow of the North American continent, and are to be preferred to the imported article in every respect. The experts of Europe, who are without doubt far in advance in the practical use of the ski, for either business or sport, have come to regard them as superior to the snowshoe for covering distance and general cruising. The armies of Northern Europe have almost exclusively adopted skiis after competitive trials of them with the Canadian snowshoe. While Norway and Austria have settled this matter by the adoption of the ski for Amy use, Canada still maintains the supremacy of the snowshoe. The battle is still on and the wise lover of winter will contribute his mite to the controversy by testing both, since there are delights to be had with each which the other does not supply. The ski is generally made of ash of the very best quality, or hickory. Some of the skiis of Northern Europe are made of elm, but the imported skiis of that wood have not proven satisfactory. Spruce has also been tried out, in Michigan, but without improvement over ash. Few of the implements for sport require such care in the making and such accuracy of design. While the expert can manage to get along on poor skiis, or crooked ones, it is the height of folly for the amateur who cares about perfecting himself in the sport to learn on anything but well made, correctly shaped and accurately balanced skiis.  "Kick Turn" first, second, and third position. Image from "Spalding's Winter Sports," by James A. Cruikshank, 1917. Ray Ruge Collection, Hudson River Maritime Museum. "Kick Turn" first, second, and third position. Image from "Spalding's Winter Sports," by James A. Cruikshank, 1917. Ray Ruge Collection, Hudson River Maritime Museum. Among the experts of the north the length of the ski is generally determined by stretching the hand over the head and selecting a pair that reach to the wrist. “Long” ski would be to where the fingers bend at the second joint; “short” ski to six inches over the head. For general use, hill climbing, touring, and even for jumping, the average or the short ski is the best. Short, stiff legged people should select a short ski, else the important kick turn cannot be executed, and on this movement depends much of the cruising ability of the ski devotee. Long skiis are best only on level stretches and flat country. There is a slight upturn at the toe of the ski made by steaming and bending the wood to a metal form. The farther north one goes, the higher this bend is generally carried. Four inches is a correct average for general use. The ski should be slightly wider at the front than at the tail. The wearer’s foot is placed about two-fifths of the distance from the tail of the ski, by which arrangement the bulk of the weight of the ski is forward of the foot. The groove is now almost universally used and runs either the full length of the bottom of the ski or to a place slightly forward of the foot. This groove tends to keep the ski straight, to steer it, so to speak, and is most important on hill descents. The foot binding is of the greatest importance. It must be rigid, yet not bind the muscles of the toes or ankle. A heavy boot is essential, or one with a very heavy sole, which is crowded or drawn firmly into the toe fastenings and then the straps fastened so they will not give. On the firmness and rigidity of the foot binding depends almost wholly the ability of the beginner to make rapid progress in the sport. There are two forms of foot bindings, the toe and the sole patterns. The sole pattern is almost unknown in the United States, although it is ranked very high by the experts of the Tyrol and the Norway chutes. The toe binding consists of a firm metal piece which is run through the ski, bent up on either side of the sole and fitted to hold the foot rigidly in place. Straps run from this metal piece over the toes and also back around the heel, being kept from slipping off the shoe by a small leather strap passing over the instep. This is the best of the toe fastenings. The usual accompaniment of the ski expert is one or sometimes two sticks used to press against the snow on the level or to steer or brake in descending hills. When but one stick is used it is generally from 6 to 8 feet in length and of bamboo; when two are used they should not be over 5 feet in length. All sticks should be equipped with leather wrist thongs and have spikes at the bottom and rings of wood firmly attached about 6 inches from the bottom. It is better for the beginner to learn with one long stick and occasionally, as he progresses in confidence, to discard the stick for considerable periods of time, so as to increase his perfection of balance. Contrary to general belief, Skiing does not require great muscular power. It is a matter of skill of balance, a knack such as one learns in swimming. For this reason it is much better to secure a teacher, if that be possible, who will at least start the beginner right and save him from learning many things which he must later unlearn. There are nice points in the sport which no type can convey, but which the eye will instantly perceive as they are executed by the expert. Failing the advantage of a teacher note these points: Do not try coasting or jumping the first thing. Much better to learn how to get up the hill, either by the hard and difficult “herringboning” method, the easier “tacking” or the simplest of all methods, “side stepping.” When you do come down remember that if the snow is damp and sticky you must lean back, while if it is dry and frozen you must lean forward. It has been wisely said that when man starts to go down hill all nature seems greased for the occasion. No man appreciates that as much as does the ski amateur. Every tree is a magnet, every stump and every rock beckons your unmanageable “planks” straight towards destruction. Study the snow, its condition, the effect of the sun on it; sometimes there is fine sport to be had on north slopes when none can be had elsewhere. Learn the sort of snow that makes for speed, for difficult climbing, for easy touring, and adapt your work for the day to the conditions. The expert ski runner knows the changing and changeableness of the snow as few men do. Snow with breaking crust is dangerous, for many reasons, while a solid crust is great sport. Avoid tracks made by others, especially in hill coasting. The fundamental things to learn in Skiing are: Darting, which simply means running downhill with skiis close together and parallel; Steering, which is done by leaning toward the side one wishes to go; Stemming, or Braking, which is done by skiis against the snow, and Slanting, which means taking a hill on an angle, a sort of “tacking downhill.” All of these movements are of almost equal importance, and should be practiced faithfully if the beginner would achieve a place in the sport or get the most fun out of it. Stemming needs but a simple diagram to explain its meaning, and Steering cannot be taught by any book; its balance is a thing which can only be learned by experience and many falls. No amount of book learning will make a ski runner expert at the sport, and the best of all the foreign books on the subject, published in the home of the sport, entirely evades the subject of Ski Jumping; nevertheless it is probable that some advice as to that important department of the sport will be welcomed. But the beginner must look more to practice than to advice. Start first without any take-off. Learn every balance with and without a pole; poles are never used in serious jumping. Gauge the stickiness of the snow and adjust your balance on arriving back on the snow after the jump to the resistance; if sticky snow, lean backward; if slippery, lean forward. Do not practice where the take-off lands you on flat ground; it is dangerous. There should be greater drop after the jump than before it. Hold your arms rigid while in the air. On touching the snow, the right foot, or one foot, should slightly precede the other.. Have the tails of the skiis touch the snow first, so as to act as rudders and get correct position. And expect ninety per cent. of falls to jumps for the first hundred jumps. Clothing for Skiing should be hard close-woven wool. Hairy goods catch the snow and soon become wet. Neck and wrists should be fitted tight and a puttee or binding of cloth about the shoe top, enclosing the long trousers or closing the opening for snow in the shoe tops is important. There is an adaptation of Skiing which is great fun and consists of employing a horse to drag the ski runners about the country, or to the top of a hill where they may coast down. Long strings of ski experts are thus met with in Norway and Switzerland, and the merriest of sport is associated with the novelty. Trips to nearby towns or places of interest can thus be made, where a meal can be had, and the return trip can be done cross country or again by horse power. AuthorJames A. Cruikshank was an expert on outdoors sports during the first half of the 20th century. Born in Scotland but spending most of his life in New York, he was the editor of The American Angler magazine, Field and Stream, and wrote numerous articles for a wide variety of other magazines and newspapers throughout his career, including the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. He also published at least three books: Spalding’s Winter Sports (1913, 1917), Canoeing and Camping (1915), and Figure Skating for Women (1921, 1922). He also contributed a chapter on artificial lures to The Basses: Freshwater and Marine (1905). In addition to his writing, Cruikshank was involved in public speaking, doing talks on outdoor sports sometimes illustrated by motion pictures. An avid photographer, Cruikshank’s photos often featured in his illustrated lectures, his articles, and his books, as he encouraged readers to take their own cameras out-of-doors. He had a home in the Catskills as well as a home and offices in New York City, and in the 1930s he helped found the Hudson River Yachting Association. At one point, he managed the Rockefeller Center ice skating rink, and another in Rye, NY. His wife Alice was also an avid camper and hiker, and they often traveled together. In 1909, Alice went “viral” in newspapers around the country by being the first person to blaze a trail between Mount Field and Mount Wiley in the White Mountains of New Hampshire (James brought up the rear). James and Alice eventually moved to Drexel, PA and were vacationing in Lake Placid in July of 1957 when James died unexpectedly at the age of 88. Skiers, what do you think? Does Cruikshank give good advice? Stay tuned for another chapter next week.

If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today! Today's Media Monday treat is all about ice boating! This short film, produced for British Pathe, shows ice boats speeding around Greenwood Lake, which is on the border between New York and New Jersey. Great footage of how the ice boats operated. The film was produced by British Pathe for the LNER (London North Eastern Railway) line in Britain, which had a cinema car on its trains designed to show short newsreels like this one for the entertainment of passengers. Yes, Greenwood Lake iceboats were being viewed in London! If you'd like to learn more about ice boats, be sure to visit the Hudson River Maritime Museum, which has two ice boats on display. You can also read and watch more by exploring the Ice Boats category on the history blog. To learn more about railroad cinema cars, check out "Inside the Cinema Train: Britain, Empire, and Modernity in the Twentieth Century" by Rebecca Harrison for Film History (2014), available on JSTOR. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

|

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 [email protected] Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |