History Blog

|

|

|

|

|

Editor's Note: This article was originally published on January 12, 1896 in the Chicago, Illinois The Daily Inter Ocean. The tone of the article reflects the time period in which it was written. New York, Jan. 10 – Special Correspondence. – The most popular new sport of the winter is golf on ice. This is like golfing on land, with a few important differences, but the persons who golf upon the ice are the same ones who golf on land. The popularity of the sport will not allow it to die during the months when the earth is covered with snow too deep for running across the links on land. In the neighborhood around New York the most popular place for ice golfing is the Hudson River when it is frozen stiff as a sheet of ice and is covered with snow, from up above the Palisades down to where the river finds the harbor. The way to play golf on ice is to mount upon skates and chase a ball over a certain course. So far it is like golf on land. The necessary attribute of golf on ice is that one should be a very expert skater, and that one has endurance and strength and can be comfortable in cold weather. When the Gould family went up to the ice carnival at Montreal just a year ago upon that memorial tour when Count de Castlane proposed to Anna Gould, one of the prettiest sights they saw was the Montreal ice golfers. Pretty English girls with warm clothes and red cheeks swung the golf sticks high in the air and made flying descents upon the ball, chasing it as though on wings. A game of golf on ice progresses faster than a game of golf on land, and more space is covered in one link than there is in a whole country golf course. The girls of the Hudson – those hearty daughters of millionaires who persisted in living along the banks of “the Rhine of America” most of the year – began ice golfing this winter. Their plan is to lay out links in the form of a course. The course is marked by a trail of fine dark sand, which is sprinkled upon the ice or upon the snow that covers the ice of the river. There isn’t over a handful in a mile of trail, but it is enough to mark the course. The “Tee” in a Pile of Snow The “teeing hole” lies upon the bank of the river. You start your ball along the trail, keep it going with as few strokes as possible on account of the score, and finally drive it ashore and into a “tee.” The second link lies farther on, and on the ice in this case is on the opposite shore of the river, maybe a mile across. All skate along to see fair play and the little caddy keeps close to the player’s heels. On the return course the trail lies down the middle of the river, and the tee is a pile of snow with a hole sunken in it for the ball. This is very difficult to “make,” as the smoothness of the ice and the smallness of the hole carries the ball on and around instead of in. But it can be done. The etiquette of the teeing ground is the same on ice as on land. Not a word must be spoken at the tee, until the ball has been safely landed in the hold. The length of a proper golf course on ice, instead of being the regulation distance of five miles, is always twenty-five. Those who do not care to skate can drive along the river bank, or upon the ice, and watch the game. If a millionaire could buy ice ponds with money it is sure that George Vanderbilt would have golfing on ice at the opening of his home, Biltmore, in North Carolina this week. Every other outdoor sport has been provided. There is a beautiful pond there that occasionally freezes over, but the crust is never thick enough for so many players and their spectators. But there are all things in readiness for golf on ice, and if the cold snap comes they will have it. The Seward Webbs, whose Shelbourne farms, in New England, is the ideal country place in the world, have a lovely winter golf course that lies over a frozen lake. When the land is passed and the player reaches the lake she has her caddy slip on skates, and the two strike out after the ball. The tools required for golf on ice are the oval and flat ones. The round and pointed sticks and clubs are not needed. There are no obstructions on the ice like fences, but there are snowdrifts that require a frequent lofting of the ball. In fact, for golf on ice a particular science is required. The average player would strike straight ahead and be obliged to come back and, finally, waste more time in returning than would be allowed for a good game. Back upon the Rockefeller country places that adjoin each other in the Tarrytown region there is a lovely spot that nestles quietly enough in the hills to tempt another Rip Van Winkle to lie down for a long slumber. To this spot the golf craze has penetrated, and a little house has been put up for the players. They gather in her as though in a clubhouse, get warm, eat little luncheons, and start out upon the chase across the ice. They can easily cover twenty-five miles in an afternoon’s golfing on ice. Expert Girl Golfers Hitherto the Meadow Brook Club people (who entertained the Duke of Marlborough on the hunt when he was here, and who bring their guests from the Pacific coast every fall for the hunting) have languished during the deep-snow season; but this fall the waters nearest them, the sound, the bay, the open bit of harbor, wherever there is a strip of ice, have been called into play for ice golfing. There may be as many links as one pleases, according to their newest rules, all to be decided the day before by a committee, which is governed by the state of the weather and the ice. Golfing upon the ice is a special sport with the young millionairesses and debutantes. They have opportunity for so many pretty poses. Nothing is more graceful than skating, and the playing of a game upon the ice is bewitchingly becoming. A very clever ice golfer is Miss Amy Bend, the very blond, baby-faced young woman, in her second or third season, who is reported engaged to Mr. Willie K. Vanderbilt. Miss Bend golfs in the Shelbourne Farms house parties and at the many country places where she is a guest this winter. Mrs. Ogden Mills and Mrs. Burke-Roche, both of which beautiful matrons are the mothers of twins, skate a great deal, with their children with them. Mrs. Burke-Roche, with her two sturdy boys, and Mrs. Mills, with her pretty little girls, can be seen skating every pleasant day. Their favorite spot is a club ground in New York City, upon which there will soon be built a set of golf links. The Western young women who own large country places, like Miss Florence Pullman, have a way of their own in planning links. A short time ago a professional golf linker who was engaged to lay out links at Lenox visited Miss Pullman’s country place in the West to get ideas from her. Her course is a very pretty one, and differs from others in having the tee holes situated in the prettiest portions of the ground. This is contrary to rule, as beauty of scenery is supposed to detract too much from one’s interest at the teeing time. If Miss Pullman follows the new winter golf fad, and has links upon the ice, she will doubtless invent a new way of making the golf links novel. There is a certain young heiress in this country. She is a Western girl, though cosmopolitan, having lived all over the world, and she is original in taste. A short time ago, when the lake upon her country place where she went for the December holiday began to freeze, she began lamenting that she could not play golf on ice. “I hear they are doing it at Fifi’s country place,” said she, mentioning the nickname of a girl well known in society, and I don’t see why I can’t do the same.” An Heiress’ Dream Straightway she had her landscape gardeners set to work to make a golf link upon the ice. The lake was a smooth, round sheet, and the course was to lay around it. The first obstacle planned was a mound of ice. This was made by packing snow upon the crust of the ice and pouring water upon it. The next obstacle was a miniature falls, with icebergs and icicles. This the gardener had his men make by pouring water slowly down upon the ice letting it freeze in midair as it would. After many tubs of water had been poured, the ice took on the appearance of a frozen falls. In playing golf upon the ice, where obstacles have been placed, the skill of the player is taxed to strike the ball just hard enough to lift it over the obstacle. He then skates around it and finds his ball upon the other side. This would be simple enough if he were sure of lifting the ball over the obstruction. But he can only “loft” with his full strength and then skate around. He not wait or the ball will have gone a mile ahead of him over the frozen surface, and a hundred feet past the tee, which is just the other side of the obstacle. There will have to be a new code of golf instructions written for those who golf upon the ice, because the summer golfing is different in everything but principle. But that will soon be done, as several young men who have fallen in love with the sport are at work upon it. HARRY GERMAINE.” AuthorThank you to Hudson River Maritime Museum volunteer George Thompson, retired New York University reference librarian, for sharing these glimpses into early life in the Hudson Valley. And to the dedicated museum volunteers who transcribe these articles. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

0 Comments

The Nantucket Girl's Song is a witty poem found in the journal kept by Eliza Brock, wife of Peter C. Brock, master of the Nantucket ship Lexington on a whaling voyage from May 1853 to June 1856. It sums up how many women felt about their husbands being off on whaling voyages for years at a time. Verse attributed to Martha Ford Russell, Bay of Islands, New Zealand, February 1855. Susan J. Berman, songwriter and interpreter at the Nantucket Historical Association, has set this poem to music and added a verse of her own NANTUCKET GIRL’S SONG - LYRICS By Susan J Berman (verse) Well I’ve made up my mind now to be a sailor’s wife, Have a purse full of money and a very easy life. For a clever sailor husband is so seldom at his home, That a wife can spend the dollars with a will that’s all her own. (chorus) So I’ll haste to wed a sailor and I’ll send him off to sea, For a life of independence is the pleasant life for me. Oh but every now and then I shall like to see his face, For it always seems to me to beam with manly grace. With his brow so nobly open and his dark and kindly eye, Oh my heart beats fondly whenever he is nigh. But when he says goodbye my love I’m off across the sea, First I’ll cry for his departure, then I’ll laugh because I’m free. (verse) I will welcome him most gladly whenever he returns, And share with him so cheerfully the money that he earns. For he is a loving husband, though he leads a roving life, And well I know how good it is to be a sailor’s wife. (chorus) So I’ll haste to wed a sailor and I’ll send him off to sea, For a life of independence is the pleasant life for me. Oh but every now and then I shall like to see his face, For it always seems to me to beam with manly grace. With his brow so nobly open and his dark and kindly eye, Oh my heart beats fondly whenever he is nigh. But when he says goodbye my love I’m off across the sea, First I’ll cry for his departure, then I’ll laugh because I’m free. (verse) So Nantucket girls please hear me and join in with this song, Hold fast to the tradition of great women brave and strong. For the women steer this island quite well there is no doubt And do the things most other girls can only dream about. (chorus) So I’ll haste to wed a sailor and I’ll send him off to sea, For a life of independence is the pleasant life for me. Oh but every now and then I shall like to see his face, For it always seems to me to beam with manly grace. With his brow so nobly open and his dark and kindly eye, Oh my heart beats fondly whenever he is nigh. But when he says goodbye my love I’m off across the sea, First I’ll cry for his departure, then I’ll laugh because I’m free. Oh yes, First I’ll cry for his departure, then I’ll laugh because I’m free. Source: https://susanjberman.com/track/1456721/the-nantucket-girl-s-song If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's Note: This account is from the December 1, 1878 St. Louis (Missouri) Globe-Democrat. The tone of the article reflects the time period in which it was written. A PAIR OF HEROINES. The Ladies Who Guard a Hudson River Lighthouse. Deeds That Would Honor Grace Darling or Ida Lewis. [From the New York Mercury.] ‘‘If the world knows little of its heroes, it knows less of its heroines.’’ So declared an old Hudson River pilot, who had for thirty years felt his tortuous way, night after night, along that serpentine stream in the pilot-house of one or another steamboat. And when he looked in that far-off-way, with his eyes turned inward, the writer knew he was thinking of something interesting, and the Mercury reporter said to him: "Come, out with it, Uncle John; tell me what you have reference to.’’ "I mean,’’ said he, with an emphatic knock given with his iron knuckles upon the table, ‘‘that while some chance incident, or the presence of a newspaper reporter at an opportune moment, gave the world the benefit of an adventure of Ida Lewis — which turned out to be merely the escapade of a masculine and hoydenish woman after all — the meritorious efforts of TWO REAL HEROINES, modest, retiring, made without any idea that the reporters were around — and indeed they were not, for a wonder — are never spoken of." "Who are the two heroines?’’ Well, they live in a lighthouse not over 120 miles from New York, on the Hudson River, keep it themselves, and I tell you they’re like the ten wise virgins in Scripture — their lamp is always trimmed and burning, and on a foggy night when the light is not visible you can hear one of them a mile off blowing a fog horn herself; for the Government has been too mercenary to give them one of the automatic new-fangled kind —and as for saving lives I know they’ve done it many a time. But if you want to know more about them, just you go down to the Government Lighthouse Bureau at Tompkinsville, on Staten Island, and they will tell you all about the heroines of Saugerties Light." The writer, with such promise of good things, could not resist the temptation to go to the Lighthouse Department, and when the object of his visit was made known to Maj. Burke, the chief clerk in the Inspector’s office, the latter said he had no doubt that the old pilot’s statements were true. ‘‘In fact,’’ said he, "there is no one connected with the lighthouses of the government whose general characteristics, daring, bravery and invincibility to fear, but withal natural modesty, would be so apt to include heroic action as MISS KATE C. CROWLEY, the mistress and keeper of Saugerties Lighthouse. While we have had no official report of her achievements, I have heard of them through other sources, and can say to you that she is capable of any daring deed involving danger or self-sacrifice; and it is the most natural thing in the world, as she is so modest that we should never receive official reports which could come only through her. As to the manner in which the lighthouse is kept, it is unexcelled by any other man or woman in the department. Accounts are always kept right, the light is always burning, and Miss Crowley is the very best kind of a keeper. Go and see her. She is a model watcher.’’ With such assurances the reporter could no nothing less than follow the advice, and he took the night boat for Catskill, which would reach Saugerties early in the morning. It was a bright, starlight night, and the writer sat in the pilot-house talking to the Steersman, who guided the steamer safely through the shadows of the frowning peak of the Highlands and answered questions or volunteered information between the rotations of the wheel. As we turned a bend in the river a light which looked like a star of the first magnitude twinkled and shown upon us far away in the distance. "That’s fifteen miles away," said the man at the wheel. ‘‘That’s Saugerties light. We'll lose it again a dozen times in the turns of the river. Do I know who keeps it? Well, no; not to speak to ’em, but know its two gals as has got grit enough, for I’ve seen ’em on the river many a time by daylight pulling away a great heavy row boat that no two river men would care to handle in one of them gales that comes sweepin’ down through the mountains like great flues in a big chimney. It ain’t like a tumultuous sea, hey? Well, that just shows how little you know about these North River storms. Why, when we get some of these hurricane blasts, they sweep down through these gaps from the north, and another current comes up from the south, and GOD, HELP ANY VESSEL that gets caught in the maelstrom when they meet. Well, it was on one of those occasions I was comin’ up the river on the old Columbus after she’d got out carryin’ passengers and took to the towin’ business. Let me see — that was about five years ago. We'd got a little north of Rondout, and I was all alone at the wheel; I heard a rumblin’ behind me, and I looked around, and when I saw a big cloud with thunder heads rushing up from the south I knew we were going to catch a ripper. This was nothing, however, to the heavy clouds that came sweeping down from he north, in an opposite direction; and then I saw that the two storms would meet. I hollered down the trumpet to the engineer to slower the engine, and made up my mind to keep headway and stay in the river, as it would be unsafe to try and make a landing or get fastened to a dock. In a few minutes the two storms struck us. The boat cavorted like a frisky horse, and in the foaming water plunged and reared, and shook in every timber, as if it had the ague. We were then pretty nearly abreast of Tivoli, and Saugerties’ Lighthouse was only about two miles ahead. A sloop loaded with blue-stone, which had just emerged from the mouth of Esopus Creek and was standing down the river, went over when the squall struck her as suddenly as if a great machine under the water had upset her; and soon I saw two men struggling in the water. Hardly a minute elapsed before TWO FEMALE FORMS were fluttering around the small boat by the lighthouse. In another minute it was launched and it bobbed up and down in the seething, foaming waters. The two girls, bareheaded, with a pair of oars apiece, began pulling towards the men in the water. The waves ran so high, the gale blew so madly, the thunder roared so incessantly and the lightning flashed in such blinding sheets, that it seemed impossible for the women ever to reach the men, to keep headway, or to keep from being swamped. But they never missed the opportunity of a rising billow to give them leverage, and they managed by steady pulling to get ahead until they reached the men in the water. The great danger was that the tossing boat would strike the sailors and end their career, but one of the gals leaned forward over the bow of the boat, braced her feet beneath the seat on which she had been sitting, stiffened herself out for a great effort, and as her sister kept the bow of the craft crosswise to the waves, caught one of the men beneath the arm as he struck out on top of a billow, lifted and threw him by main force into the middle of the boat, and then PREPARED FOR THE OTHER MAN. He had got hold of the sloop’s rudder, which had got unshipped and was floating on the water. He let go and swam toward the rowboat, and was hauled in also by the woman and his half-drowned comrade. I tell you,’’ said the pilot, ‘‘those gals are bricks, and no mistake. You couldn’t have got any river boatmen to do what they did.’’ It was just 4 o’ clock when the steamboat landed at the little insular dock which is called Saugerties, but which ought to be called Gideonstown, for there is only one house in it, and that is inhabited by a most estimable family by that name. The sight from the lighthouse, however, full a mile away, shone down upon it like the eye of a great ogre, illuminating the surrounding country, and enabling the writer to take observations. These, however, were more certain in the light of dawn which soon followed. From Mr. Gideon it was learned that the village of Saugerties was two miles away, and that there were many old residents in that place, where the parents of Miss Crowley formerly resided, and along the river front, who were familiar with the exploits of the young ladies. "Do I know them?’’ was his interrogative answer to the reporter’s question. "I should like to know who doesn’t know them hereabouts. They are always in their boat, and the people hereabouts have come to think that they REALLY BELONG TO THE WATER more than they do to the land, for the only time they are visible is when they are rowing to Saugerties or other places to get provisions for their household. They do that every day, rain or shine.’’ "Do they mind rain?’’ "Not at all, they make visits every day Saugerties or thereabouts. As for rowing, no boatman on the river can equal them. They feather their oars and make regular strokes independent of wind or tide." A trip to the village of Saugerties after much inquiry, led the reporter to a person who had been familiar with the lighthouse and its surroundings for many years. He is an old boatman and fisherman. He catches shad at the season of the year that they abound, and goes out duck shooting in the fall and early winter. He is acquainted with the history of all the inhabitants, and knows all about the occupants of the lighthouse since it was first built. THE TALE OF A LIGHTHOUSE. He said: ‘‘It is now twenty years since Mr. Crowley was appointed lighthouse keeper. The old light stood on a piece of masonry which was built midway in the river, upon a morass several feet above the surface of the water at high tide, but in a very unsubstantial way. When the early spring freshets brought down the ice, it was feared several times the lighthouse would be carried away, and the necessity of a new foundation and a new lighthouse soon became apparent. The old place, however, was newly supported, and about fifteen years ago he brought over his family from Saugerties to live in the building. His daughter Kate, a little girl then, from first seemed to be amphibious, and she would go out in a little skiff from the lighthouse alone, seeming to take such risks that every one prophesied that she would surely be drowned. Many a time her little craft upset, but SHE SWAM LIKE A DUCK, and always succeeded in reaching the lighthouse in safety. Her sister Ellen during these early years lived at her relatives in Saugerties, and did not join her sister until the new lighthouse was built. That was about nine years ago. Then Kate was fifteen years of age and Ellen about seventeen: In that year, Ellen was leaving Saugerties in a boat with her mother, and she saw a boy in swimming, but who had got beyond his depth, struggling for aid. She endeavored to reach him and her mother attempted to assist her, but, the latter being a woman weighing over 200 pounds, upset the boat, and the girl was thrown into the water in such a way that she came under the boat, which had capsized. Her mother was speedily rescued, but the daughter could not release herself from the peculiar position in which she was placed for several minutes and when rescued was found to have taken a considerable amount of water into her lungs. This seriously affected her health for some time afterwards. She has suffered more or less from that immersion, and malarial fever from that time to the present moment, and though she and her sister are said to take care of the lighthouse, and are always together in an emergency, the latter of late years has taken the responsibility of the place herself and runs the whole affair. Do I know of any case where these girls have saved life? Indeed I do. Three years ago last winter, A YOUNG MAN AND A LADY attempted to cross the ice to Tivoli. They had got about 100 yards from the lighthouse when the ice broke and they were precipitated into the water. Kate had rigged her boat with runners, so that, in her regular trips to main land, she was able in winter weather to make her way over the ice, or the latter gave way, through the water. She appears to be always on the lookout, and saw what had occurred, and in an incredible short space of time jumped upon the ice, pulling her boat after her, while her sister pushed it from the stern. They arrived at the scene of danger speedily and rescued the young man, but his companion had disappeared. Kate saw a fragment of her dress floating on the water, and knew that she was under a cake of ice. It took but a moment for Kate to rush forward, throw herself into the opening and withdraw the woman from her perilous position. The latter was limp and senseless, and it took several minutes to restore her to consciousness. Meanwhile the ice was breaking up all around the boat, the young man was precipitated into the water, and it required the UNITED EFFORTS OF THE TWO SISTERS to recover him also and place him in the boat. During this time gorges of ice had broken up above, and had carried all of them far below, and it was by the utmost efforts of the sisters that they succeeded in reaching a point two miles below the lighthouse. It is only about two-years since a steamer ran into a sloop nearly abreast of the lighthouse, cutting the latter in two and throwing all on board into the water. The sisters immediately launched their boat and put off to the assistance of the men in the water. Two of the sailors could swim, and in a few moments succeeded in reaching the bar, but two others were struggling for life. One of them had gone down twice and was rescued as he rose the third time. A fourth one was hanging to a piece of the wreck, when he was TAKEN INTO THE HEROINES’ BOAT. "These circumstances,’’ declared our informant, "have come under my personal observation, but there are many other cases well substantiated, in which these girls have saved life, but the particulars of which I am not informed.’’ AT THE LIGHTHOUSE. The writer, returning to the long dock, was conveyed to the lighthouse in a row-boat by Mr. Gideon. The place consists of a frame house and an adjoining lighthouse, erected upon a stone foundation built upon the flats. There are no grounds around the house, and consequently no opportunity for raising anything. Stone steps extend in the south side of the masonry to the water, and up these the writer ascended. Several raps at the front door failed to meet with any response, and the reporter walked around the narrow stonework to a side door. A single knock at this brought to the door a young lady, who was evidently surprised at the presence of the visitor. The latter asked for Miss Kate Crowley. The young lady replied that she was the person asked for, and invited the visitor into the front room, which was used as a parlor, and was plainly but neatly furnished. It hardly seemed possible that the modest appearing, FAIR-HAIRED, BLUE-EYED YOUNG LADY could be the heroine spoken of, but there seemed to be no question of doubt, and the reporter suggested that as he had ascertained she had been instrumental in saving life, he should pleased to get the particulars from her lips. She seemed exceedingly loth to say anything about herself, especially in the way of exploits, and when the reporter mentioned the instances spoken of above, she turned them off as of no account, or not worth elaboration. Considerable of her history was gleaned independent of her life-saving exertions. She said that when she was a little girl her father took the old lighthouse, and she had such a fondness for the water that she used to be on it all the time in a little skiff. She liked also to take charge of the light, see that the oil was in good condition, and attend to all lighthouse matters, so that her father by the time she was fifteen years of age had come to depend entirely upon for the care of the lighthouse. About nine years ago, when the new lighthouse was built - work which she had watched at every stage of its progress with a great deal of interest - her FATHER SUDDENLY BECAME BLIND from cataract of the eyes. Her mother was unable to take charge of the lighthouse, and since that time she been compelled to assume the whole management herself with some assistance from her sister, who has always been in poor health. They row daily to the neighboring village to get their provisions and receive $560 a year as their remuneration. They have to find everything except oil and necessaries for keeping the lamp in order. They have some very severe storms sometimes, and in the spring the ice comes down and threatens their little house; but she is never afraid, and thinks it a pleasure when any one is in danger to do what she and her sister can to relieve them. During the conversation her sister came into the room. Never were two sisters more unlike. ELLEN IS A BRUNETTE, tall, slim, with dark eyes and dark hair. When Kate is animated she is exceedingly pretty. She displays a row of milk-white teeth and shows dimpled checks, and looks at you with a pair of large eyes full in the face. She introduced her sister to the reporter, explaining his visit. The new-comer was quite as indisposed to seek notoriety as the other, and said: ‘‘We are simply two girls trying to do our duty here in this quiet place, taking care as we best can of our blind father aged mother. We are always on the lookout for vessels that may get out of their course and are sure to have our lamp in good order. We have not the opportunity of making ourselves heroines as we have learned another woman, Ida Lewis, has, but we do what we can in our feeble way.’’ The writer insinuated that their romantic spot would be apt to induce visitors to call upon, them, but they declared that theirs was a most solitary life. The inhabitants of Saugerties had come to regard the lighthouse as an old institution, possessing no interest whatever; there was nothing to attract visitors but their plain house, which was certainly unattractive, and the only time they saw any one was when they made their visits to the mainland for provisions. They had an idea, too, that the locality was unhealthy. Every summer for the past nine years they had SUFFERED FROM MALARIAL FEVER, arising from the surrounding lowlands, and only a few months ago they had buried a beloved brother. The only pleasure they had in life was to row in the river, keep the lighthouse in good trim, and do the best they could for any one in trouble on the river. They introduced the reporter to their aged parents, who understood only dimly and vaguely (after repeated efforts on the part of their children to make them comprehend what the object of his visit was), and at parting, the heroic sisters asked that they might not be given too much publicity. The writer promised that he would not say anything concerning them which they did not merit, and, as he was told still more of their humane efforts after he had left their island home, he feels that he has not violated his promise. AuthorThank you to HRMM volunteer Carl Mayer for sharing and transcribing this article and for the glimpse into nineteenth century life in the Hudson Valley. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

History of the Water Song: There are many women’s water songs from many different cultures, and they all have deep meaning and beauty. The Water Song in this video has a lyric that is easy to learn and does not take a long time to sing. At the 2002 Circle of All Nations Gathering, at Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg in Ottawa, Canada, Grandfather William Commanda asked Irene Wawatie Jerome, an Anshinabe/Cree whose family are the Keepers of the Wampum Belt to write a song that women attending the gathering would learn and spread it throughout the world. Grandmother Louise Wawatie taught the Water Song to Grandmother Nancy Andry so she could begin her mission of spreading this powerful practice. Recently, in 2017, although Grandfather William and Grandmother Louise have crossed over, Grandmother Nancy met with the Elders again in Canada, and they were unified in agreement that a video of the song should be made to hasten the teaching and widen the circle of women singing it because of the increasingly grave dangers our waters are facing. The Wawatie and Commanda families gave permission to record the song on this video. For more information go to: https://www.singthewatersong.com/ If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

Editor's Note: This article is from June 5, 1887 Washington Post. Belledoni’s Latest Fad. New York Girls Now Make Trips In Canoes and Become Heroines. Special Correspondence of The Post. New York, June 3. – The canoe threatens to become femininely fashionable. A woman and a canoe – the two ought to go well together, for ever since there were women and canoes they have both had the reputation of being cranky. “The fact of the matter is, the canoe has been slandered,” said a belle, in talking about canoing for women, “until it has got the reputation of being unsafe. That is what makes it popular among the more dashing of our girls.” She and her brother have made the trip up the Hudson to Albany and back, camping out on the way, and otherwise taking advantage of all the opportunities for roughing it. “What did you wear? And what did you do with your clothes?” I asked. “You surely didn’t take Sunday bonnet along.” “I wore a blue flannel dress made all in one piece, with a blouse waist, no drapery, the skirt reaching to the tops of a pair of extra high boots. It weighed a pound and a half. I wore a sailor hat and carried a light jacket, to be ready for changes of weather. Our canoe is rather small to be used as a tandem – it measures fourteen feet by thirty inches – so that one could not have taken much luggage if we had wished. All that we carried weighed only about thirty pounds, and of this our photographic materials, plates, camera, etc., weighed between fifteen and twenty pounds.” “What did you do at night, sleep on the ground and cover with your canoe, or go to a hotel?” “We started with the intention of camping out every night, but camping places between here and Albany are not numerous and we sometimes had to stop at a hotel. But we did camp out about two-thirds of the time. We carried a small tent – made of sheeting, so that it would be of less weight than one of canvas – a blanket apiece and a rubber blanket to spread on the ground. We had a tin pail apiece, and a tin cup, tin plate and a knife each, and a few other primitive and strictly necessary articles. Then we carried a few canned meats, but not much in that line, as we expected to be able to buy most of what we would want at our camping places. In that we were sometimes badly disappointed. One evening we camped near Esopus, tired and hungry after paddling all day, and walked over the hill to the country store to find something to eat. But all that was to be had was a loaf of baker’s bread and a bundle of wilted beets. On another occasion all that we could get was some bread and milk and green plums. But usually we fared reasonably well. Then the numerous ice houses along the Hudson and the ice barges constantly going up and down made it easy to keep a tin pail full of ice chips, which seemed quite a luxury.” “You did not feel afraid tossing about in all that wind and water in such a tiny shell of a boat?” “Not in the least. I knew the canoe, and I felt just as safe there as I would on dry land. If the persons in a canoe know how to handle it and are reasonably prudent in their actions there is absolutely no danger. If they only sit still in the bottom of the boat they can’t overturn it if they try. One day we went aboard a brick barge, and the astonishment the men who ran the big, clumsy thing showed over our tiny craft was quite amusing. They considered us miracles, of course, because we were willing to go on the water in such a cockle shell and were absolutely sure that we would be upset in less than half an hour. And as for me, they could hardly believe the evidence of their eyes that I had been aboard the canoe, and nothing could have convinced them that there was another woman on the face of the earth who would dare venture in on the water.” So the belle in a canoe is something of a proud heroine. – Clara Belle AuthorThank you to HRMM volunteer George Thompson, retired New York University reference librarian, for sharing these glimpses into early life in the Hudson Valley. And to the dedicated HRMM volunteers who transcribe these articles. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

On September 22, 1897, Mrs. Edith Gifford boarded a yacht on the Hudson River along with other members of the New Jersey State Federation of Women’s Clubs (NJSFWC) and male allies from the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society (ASHPS). The goal of this riverine excursion was to assess the horrible defacement of the Palisades cliffs by quarrymen, who blasted this ancient geological structure for the needs of commerce—specifically, trap rock used to build New York City streets, piers, and the foundations of new skyscrapers. All on board felt that seeing the destruction firsthand, with their own eyes, was the first step in galvanizing support for a campaign to stop the blasting of the cliffs. The campaign that followed was successful: Women from the NJSFWC lobbied Governor Foster Voorhees, while men from the ASHPS found support in their own Governor Theodore Roosevelt. Their efforts led to the creation of the Palisades Interstate Park Commission (PIPC) in 1900 through an act to "preserve the scenery of the Palisades." Under President George Perkins, the Commission purchased or received successive tracks of land to save the Palisades from quarry operators, resulting in iconic recreational areas such as Bear Mountain State Park. When the Palisades Interstate Park opened in 1909, few could imagine that it would become one of the most popular public parks in the entire nation. A landscape marked by resource extraction became a landscape of recreation, environmental education, and nature appreciation. The yacht trip characterized the collaborative nature of this critically important conservation story. What brought these groups and others together was not only a shared interest in the value of scenic beauty and recreation, but also a desire to save the trees growing along the base and top of the cliffs—an issue tied to other environmental initiatives at the time, especially the creation of a public park in the Adirondacks to protect the sources of the Hudson River. Women from the NJSFWC, especially Mrs. Edith Gifford, joined leading forestry experts like Gifford Pinchot and Bernhard Fernow in calling for the protection of the Palisades woodlands and other forested areas across New Jersey. Unlike scientific foresters, however, Mrs. Gifford and other women focused on public pedagogy. Through their efforts, the NJSFWC prepared the way for civic education, nature study, and environmental stewardship in Palisades Interstate Park and beyond. Seeing the Forest from the Rocks In the mid-1890s, as people on both sides of the Hudson began advocating for the preservation of the Palisades cliffs, many scientists and politicians were also beginning to recognize the importance of forests to water supplies. The publication of George Perkins Marsh's bestselling book Man and Nature in 1864 generated public discussion of the potentially disastrous consequences of large-scale deforestation: When trees are destroyed, Marsh warned, the ground loses its ability to hold moisture, and the disturbed ground becomes more susceptible to erosion. Deforestation threatened entire watersheds, impacting commerce, navigation, and public water supplies. His conclusions influenced emerging forestry experts, businessmen, and politicians, ultimately leading to the creation of a Forest Preserve in 1885, Adirondack Park in 1892, and the addition of the “Forever Wild” clause to New York State’s constitution in 1894. Just as in the Adirondacks, scientific foresters in New Jersey raised concerns about the impact of deforestation on the state’s water supplies. As urban and suburban populations across New Jersey swelled, many felt that preserving water supplies and spaces for recreation was more valuable, and more feasible, than reviving timber revenues. In 1894, the NJ State Legislature ordered that a survey of the state’s forests be included in the State Geological Survey. The survey’s purpose was to determine the possibility of creating a network of forest reserves across the state to satisfy needs for water and recreation. It highlighted how the forests of the Palisades were composed of high quality, old-growth trees, vital to the protection of water supplies in the Hackensack Valley below. The survey also noted the Palisades’ value for future students of forestry. “This beautiful forest,” the report stated, “has almost as good a claim to future preservation as the escarpment of the Palisades.” The State Forester of New Jersey at the time was Dr. John Gifford, husband of NJSFWC member Mrs. Edith Gifford. Both had been active members of the American Forestry Association and shared a passion for trees. Dr. Gifford was the founding editor of New Jersey Forester, which ultimately became American Forestry, the journal of the U.S. Forest Service. Mrs. Gifford was active in numerous urban reform and environmental campaigns. After the establishment of the NJSFWC in 1894, she worked to bring the issue of forestry into the discourse surrounding the preservation of the Palisades from quarrying. A newspaper report described her this way: “Mrs. Gifford is a New Jersey woman who makes a special study of forestry for the NJSFWC when not engaged in household duties. She can tell you all about the management of European forests…[and] pathetic tales of wanton destruction of beautiful forests in this country.” In 1896, she was appointed Chair of a new Committee on Forestry and Protection of the Palisades at the NJSFWC. While scientific foresters focused on reports and surveys, Mrs. Gifford devoted herself to educating the public. At a NJSFWC meeting in 1896, which was attended by numerous state legislators and some of the nation's leading foresters, she showcased a traveling forestry library and exhibition, intended to educate the public, and especially children, about the importance of forests and forestry. The exhibition included contrasting images of ‘pristine’ forests and those ravaged by lumber dealers for economic profit; depictions of trees in art and leaf charts by Graceanna Lewis; maps of New Jersey forests and their connection to the state's geology; portraits of notable trees; and examples of erosion caused by deforestation in France and other European countries. The library consisted of a bookcase made of oak, encased in “a traveling dress of white duck.” Other women’s groups, libraries, and schools across the state could apply for the privilege of hosting it for a month. It included major forestry textbooks of the day, including What is Forestry? by Bernhard Fernow; Franklin Hough’s Elements of Forestry; tree planting manuals; and pamphlets on forestry’s importance to watershed protection and timber supplies. Sargent attended the meeting and wrote a rave review in his journal, Garden and Forest. Applauding the role of women in increasing public literacy about trees, forests, and forestry, he linked their efforts directly to policy making. "No comprehensive forest policy," he wrote, "can even be devised without a more cultivated public sentiment." The exhibition and traveling forestry library were not merely didactic tools, Sargent explained; they encouraged a sentimental connection between trees and people. The "cultivation of a sympathetic love of trees," for Sargent, was the basis for citizen involvement in forestry, forest preservation, and nature appreciation. “The arrangement of this exhibit," Sargent remarked, "was so effective that it seemed a pity that it must be transient, and the suggestion that every library and schoolroom should have something of this kind…was felt by all who saw it.” In the wake of this meeting, Mrs. Gifford’s traveling forestry library circulated in women’s clubs across the state. Clubs applied for the privilege of hosting the oak bookcase for a month at their own expense and used it to generate public discussion of forestry issues. Explaining the necessity of such a library as well as other forms of outreach—including reading circles and exhibitions—Gifford stressed the centrality of pedagogy to policy making: “Much education is needed to bring about necessary legislation and progressive methods,” she argued. Going further, Mrs. Gifford took the cause of public education and forestry to the national level. At a General Federation of Women’s Clubs meeting in 1896, of which the New Jersey State Federation was a part, she urged members across the country to take a pledge to forestry by declaring among themselves, “We pledge ourselves to take up the study of forest conditions and resources, and to further the highest interests of our several States in these respects.” Copies of the document were sent out to all 1500 local GFWC clubs as well as the press, augmenting both women’s role in forest protection and public awareness of the problem. The pledge in its entirety was published in her husband's journal, The Forester, shortly afterwards, ensuring widespread media attention. Mrs. Gifford was not the NJSFWC’s lone forestry advocate. Mrs. Katherine Sauzade, for instance, included the value of the Palisades woodlands in her 1897 speech calling for the preservation of the Palisades. Whereas Mrs. Gifford stressed the importance of healthy forests to healthy waterways, Mrs. Sauzade instead emphasized the role of trees in creating the “wild, rugged character” of their beloved Palisades. In this instance, trees functioned as part of the scenic beauty of the area; their value was not as parts of an invisible system, but as part of the visual splendor of the place. For Sauzade, destroying the scenic beauty of the trees as well as the cliffs was an attack on civilization itself. “We cannot escape,” she wrote, “the disgrace, nor the just censure of the civilized world if we permit, by further neglect, the continued defacement of these grand cliffs.” By the time the yacht set sail on the Hudson in September 1897, therefore, forestry was already a dominant interest at the NJSFWC and elsewhere in the state. On deck, watching the blasting of the cliffs of the Palisades at the Carpenter Brother’s quarry, Mrs. Gifford declared that “the forestry interest…exceeds the interest of preserving the bluffs.” Reminding her colleagues of her studies of the Palisades woodlands, she remarked that “in some places, the Palisades look exactly as they did when Hendrick Hudson sailed up the river. That is a very remarkable thing to find a primeval forest near the heart of a great metropolis.” Mrs. Gifford’s statement was supported by Joseph Lamb of the ASHPS, who built one of the first resorts on the Palisades in the 1850s. “The Palisades,” he stated on the yacht, “are perhaps more valuable as woodlands than anything else.” At a national GFWC meeting in 1898, NJSFWC President Cecelia Gaines (later Cecilia Gaines Holland), raised the issue of forestry and the protection of the Palisades once again: “There are utilitarian reasons for the protection of the Palisades,” she told club members. “The valleys at their feet are covered with farms and small towns whose water supplies are drawn from sources in the Palisades. Disturb or remove these sources by blasting and the dwellers below suffer in consequence.” From Nature Study to Nature Appreciation Despite the essential role of the NJSFWC in the creation of the Palisades Interstate Park Commission in 1900, women were excluded from the commission itself on the basis of their gender. This, however, did not stop their involvement in Palisades conservation or in forestry more generally. In 1905, GFWC President Lydia Phillips Williams declared in a speech at the American Forestry Congress that “[The GFWC’s] interest in forestry is perhaps as great as that in any department of its work…[forestry committees] are enthusiastically spreading the propaganda for forest reserves and the necessity of irrigation.” By 1912, however, women were excluded once again, this time from the American Forestry Association—the organization that Mrs. Gifford had once been a part. Environmental historian Carolyn Merchant suggests that this shift was due to the full-fledged institutionalization of scientific forestry, which was not accessible to women, or to their opposition to Hetch Hetchy. With the creation of the PIPC in 1900, interest in protecting the forests of the Palisades for water supplies continued. At the opening ceremony for Palisades Interstate Park in 1909, New York Governor Charles Evans Hughes stated that he hoped that the creation of the park was the first step in “[safeguarding] the Highlands and waters…The entire watershed which lies to the north should be conserved.” George Frederick Kunz, a curator at the American Museum of Natural History, echoed this sentiment in his own address. Pointing to the example of the Adirondacks, he said, “It must be borne in mind that without your forests you would have no lakes…until we have reforested our hills, we will not have proper water for this river.” Reforesting the Palisades through tree planting was part of the growth of the park itself. Students at newly created professional forestry programs at Yale and the New York State College of Forestry in Syracuse contributed to this process—in 1916 alone, students planted 700,000 trees. In the 1930s, the Civilian Conservation Corps managed wooded areas in Palisades Interstate Park, planted trees, and constructed new infrastructure. Forestry students also used the woodlands of the Palisades as a laboratory, studying the area’s vegetation, conducting ecological surveys, and developing forest management plans. Yet, as Palisades Interstate Park grew, the social and recreational aspects of forestry were stressed more than its importance for water or timber supplies. Given their close proximity to New York City, the value of the Palisades’ woodlands to public welfare and urban reform—key tenets of the Progressive Era—could not be ignored. In 1920, the New York State College of Forestry at Syracuse published a bulletin that outlined the value of “recreational forestry” in the Palisades. “The Palisades Interstate Park of New York and New Jersey,” it stated, “on account of its proximity to the American metropolis, is, and should be, dominated by the needs of the people in the vicinity of this great city.” In a section called “Forests versus City Streets,” the author addressed how forestry camps could improve the well-being of New York City’s low-income residents. “Outdoor influences,” he wrote, “…curb and counteract tendencies of other environments which fail to promote the ultimate good of these juvenile elements of society.” He continued, “Impossible it is to estimate the aggregate of all the impressions of associations that stir the dull soul…and influences that prompt to effort and incite nobler living.” Similarly, an ecological survey of Palisades Interstate Park in 1919 included an entire section on “The Relation of Forests and Forestry to Human Welfare.” While the survey began by discussing social forestry initiatives in Palisades Interstate Park, it concluded by addressing the public needs that inspired National Parks: “The moment that recreation…is recognized as a legitimate Forest utility the way is opened for a more intelligent administration of the National Forests. Recreation then takes its proper place along with all other utilities.” Far from city streets, park visitors experienced the wonder of the Palisades woodlands firsthand through excursions and nature study. When they left, they brought back a new appreciation for nature of all kinds. Mrs. Gifford’s pedagogical mission, therefore, was ultimately realized in the park itself. Few could have predicted in the 1890s how much of an impact the introduction of trees to a campaign to save an ancient geological structure would have. Recognition of the importance of an informed public shaped not only the growth of the park itself, but also the future of environmentalism in the United States. AuthorJeanne Haffner, Ph.D., is a landscape historian and associate curator of “Hudson Rising” (March 1 - August 4, 2019) at the New-York Historical Society. She previously taught environmental history and urban planning history and theory at Harvard and Brown Universities, and was a postdoctoral fellow in Urban Landscape Studies at Dumbarton Oaks (Harvard). This article was originally published in the 2019 issue of the Pilot Log. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

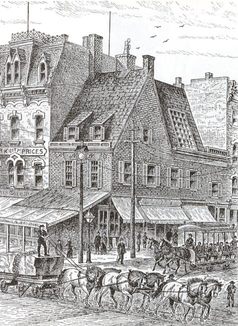

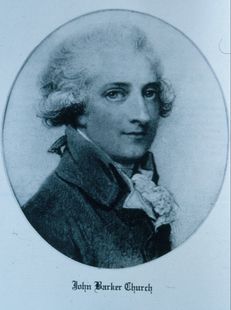

Schuyler Mansion State Historic Site has been open to the public since October 17, 1917 and will be celebrating its 100th anniversary this season. The home was built between 1761 and 1765 by Philip Schuyler of Albany who, after serving in the French and Indian War, went on to become one of four Major Generals who served under George Washington during the American Revolution. Prominent for his military career, as a businessman, farmer, and politician, Philip was the main focus of the museum when it opened in 1917. Over the last hundred years, however, the narrative told by historians at the site has expanded to emphasize the roles of Philip’s wife Catharine Van Rensselaer Schuyler, their eight children (five daughters; three sons), and nearly twenty enslaved men, women, and children owned by the Schuylers at their Albany estate. Since March was Women’s History Month, I am pleased to set aside Philip Schuyler, and instead bring you the history of the women of Schuyler Mansion – Catharine Schuyler and her five daughters Angelica, Elizabeth, Margaret, Cornelia, and Catharine (henceforth Caty to avoid confusion with her mother). Some of those names will sound familiar to fans of the Broadway show Hamilton: An American Musical. The oldest daughters, Angelica, Elizabeth, and Margaret “Peggy” Schuyler, born in 1756, ‘57, and ‘58, feature heavily in the plot because second daughter Elizabeth married Alexander Hamilton, America’s first Secretary of the Treasury, in 1780. It is largely through Elizabeth’s efforts that so much information exists about Alexander Hamilton, Philip Schuyler, and the rest of the family. Women were often the family historians of their time, collecting letters and documents. Elizabeth was particularly tenacious in this role. Unfortunately, since women’s actions were not considered relevant to the historical narrative (and perhaps due to some degree of modesty from the female collectors), sources by and about women were not always preserved. Through careful inspection of the documents that remain, however, we can piece together quite a lot about these six women.  Philip Schuyler's childhood home - a 17th-Century Dutch structure where the eldest daughters were raised before moving to Schuyler Mansion. Albany in the 18th-Century still reflected its' Dutch roots more than its' English government. Philip Schuyler's childhood home - a 17th-Century Dutch structure where the eldest daughters were raised before moving to Schuyler Mansion. Albany in the 18th-Century still reflected its' Dutch roots more than its' English government. For the Schuylers, documentation started young, with receipts and letters describing the girls’ education. In the period, core literacy was most often taught at churches where basic reading and writing were a means to an end in teaching scripture. This holds true for the Schuylers. In 1764, when Angelica was 8 years old, Philip purchased “cathecism books more for Miss Ann”. Philip additionally paid for lessons in French, dancing, geography, history, writing, and arithmetic. In combination with references to music, ornamental embroidery, and the “women’s work” which the girls most likely learned from Catharine, these lessons constituted every subject deemed appropriate for women by contemporary educational philosopher Benjamin Rush, and more. This family was well educated even amongst their peers. Catharine’s education, however, remains mysterious as no letters in her handwriting exist. Given her social status, it is unlikely that she was illiterate. However, it is possible that she was literate only in Dutch, as approximately half of Albany still spoke Dutch as their first language. Anne Grant (a contemporary of Catharine’s) described in A. Kenney’s Gansevoorts of Albany: “In the 1750s girls learned to read the Bible and religious works in Dutch and to speak English more or less, but a girl who could read English was accomplished; only a few learned much writing.”  This portrait of youngest daughter Catharine Schuyler shows Caty at about 12-15 years old. She is sitting in front of a piano forte. Instruments were expensive, but music was considered a fine accomplishment for ladies in families who could afford it. This portrait of youngest daughter Catharine Schuyler shows Caty at about 12-15 years old. She is sitting in front of a piano forte. Instruments were expensive, but music was considered a fine accomplishment for ladies in families who could afford it. Knowing women’s childhood education is critical to our understanding of their adult lives. Even today, education molds children to fit the ideals of the culture they live in and therefore shows parents’ aspirations for their children. In the 18th Century, the ideal for women of this social class can be defined by four main roles: wife, mother, household manager, and social manager. By educating his daughters in dance, music and etiquette, Philip Schuyler prepared them for the wealthy social scene where they would meet potential suitors. By having them learn French, they could read philosophies and poetry and other refined subjects that would be impressive to the educated elite that Schuyler hoped those suitors would be. Meanwhile, Catharine taught them the household work that would be required of them once married. Historically, women have been defined primarily by their spouses. It is a mistake to do so, however, marriage was exceptionally important for women in the 18th-Century. Under English government, women had no political rights and very limited legal, economic, or property rights. An adult woman’s power came from the influence she had over her spouse, and the influence she had over the next generation through the training of her sons. As such, at the start of the 1700s, 93% of women in the Northeast were married. This declined to 78% by century’s end, which likely correlated with a growing population of women, rather than declined need or desire to marry. While arranged marriages were fading out of style with non-nobility by the mid-18th-Century, wedding arrangements still looked quite different from today. In more liberal households, as the Dutch tended to be, a woman had a fair amount of say in who she was to marry, but only so long as she was marrying from within an appropriate social circle. Parental permission was still required and a suitor who brought in political or property assets was preferred. Romantic love (or attraction - the term “romantic” was not yet used as we think of it today) as a prerequisite for marriage was gaining popularity, but was not considered necessary. Marriage was often treated as an economic pact. If love existed or developed, it was a bonus. There are two marriages in the Schuyler family that are key to understanding this family’s dynamics - Philip Schuyler’s marriage to Catharine Van Rensselaer in 1755, and eldest daughter Angelica’s marriage to John Barker Church in 1777.  Catharine grew up in the heart of the Van Rensselaer property in Greenbush, now the city of Rensselaer. Her parents' home, Crailo, still stands as another New York State Park. Catharine grew up in the heart of the Van Rensselaer property in Greenbush, now the city of Rensselaer. Her parents' home, Crailo, still stands as another New York State Park. Philip and Catharine’s marriage mostly fit the cultural ideal described above. Both were fourth generation Dutch, meaning that their great-grandparents were the first to come from the Netherlands in the mid- 1600’s. Philip’s family made its fortune in the beaver fur trade and supplemented their income through land speculation and marriage. Meanwhile, Catharine’s family came over as part of the Dutch Patroon system. Akin to a feudal system in some ways, Patroonships gifted land to wealthy Dutch families in order to colonize New Netherland, which later became New York. By the time of Catharine’s birth, her father owned more than one hundred and fifty thousand acres of land throughout the colony. Not only was the couple from the same wealthy elite social circle and approved of by both families, they had a seemingly romantic courtship. In letters before their marriage, Schuyler asked his friend Abraham Ten Broeck to pay his regards to “Sweet Kitty VR” if he should see her.  Philip and Catharine likely expected their children would also marry with wealth, education, and family approval in mind. Angelica’s marriage broke those expectations when, in 1777, she married an elegant young commissar who called himself John Carter. Carter came to the home to settle military accounts with Philip Schuyler. While Carter looked the part of the wealthy, well-educated man, Philip knew nothing of Carter’s family and worried about his connection with Angelica. No one could tell Philip more about “Carter”, because this was an assumed identity. The man was actually John Barker Church, a broker from a prominent family in England. Church fled to the colonies to escape gambling debt, and possibly fallout from a duel. Either unconcerned with her suitor’s background, or uninformed of it, Angelica married John Barker Church without parental permission. As a result, she was disowned and forced to take up residence with her maternal grandparents in Greenbush. She stayed with them only two weeks before her grandfather coaxed Philip and Catharine to meet with the couple and forgive them. It is unclear if Church revealed his identity to the Schuylers at that time, as the couple continued to be known as the “Carters” until the end of the war. After this marriage, Philip no longer had the confidence that his children would marry under the ideals of the time, and because he was so quick to forgive Angelica, his children saw this as precedence. At least three more of the eight children eloped. Second daughter Elizabeth married with permission, but Angelica’s elopement clearly still weighed heavily on Philip’s mind when he responded to Alexander Hamilton’s request for Elizabeth’s hand in February of 1780: “Mrs. Schuyler[...] consents to comply with your and her daughter’s wishes. You will see the impropriety of taking the dernier pas [fr: last step] where you are. Mrs. Schuyler did not see her eldest daughter married. That gave me also pain, and we wish not to experience it a second time.”  The formal parlor at Schuyler Mansion where Elizabeth Schuyler married Alexander Hamilton on December 14, 1780. The formal parlor at Schuyler Mansion where Elizabeth Schuyler married Alexander Hamilton on December 14, 1780. The formal parlor at Schuyler Mansion where Elizabeth Schuyler married Alexander Hamilton on December 14, 1780 Hamilton was far from Schuyler’s ideal. He was an orphan raised in poverty in the Caribbean with no land, money, or family ties. And yet, Schuyler hesitantly said yes. Perhaps it was only Hamilton’s military career under George Washington that earned Philip’s approval. Or, perhaps the question lurked at the back of Philip’s mind: “if I say ‘no’… will they marry anyway?” Philip maintained control over the situation by asking the pair to marry at Schuyler Mansion, forcing them to wait until Hamilton could take military leave. The couple married in the formal parlor of Schuyler Mansion on December 14, 1780. The next in line was Margaret, nicknamed Peggy. Unlike her sisters, Peggy married close to home in 1783. Stephen Van Rensselaer was a cousin on her mother’s side. The relationship was very near the ideal set forth by their parents. It strengthened the family’s connection with one of the wealthiest Dutch families in Albany. In fact, after inheriting the bulk of the Van Rensselaer estate at 21 years old, including his land holdings - approximately 1/40th of New York State – and accounting for inflation, Stephen ranks 10th on Business Insider’s list of the wealthiest Americans of all time. There are rumors that Peggy and Stephen eloped, but very little evidence to support it. A relative of Stephen’s reacted with surprise that Stephen, then 19, married so young, especially since his bride was 25, but there was no surprise or outrage from either parents. There was no question that this was a powerful match. The next Schuyler daughter, Cornelia, was 17 years younger than Peggy, but despite the age gap, the influence of Angelica’s marriage still held power. Cornelia eloped in 1797 with Washington Morton, an attorney from New York who appears to have attempted to gain parental permission but, in his own words: "Her mother and myself had a difference which extended to the father and I had got my wife in opposition to them both. She leapt from a Two Story Window into my arms and abandoning every thing [sic] for me gave the most convincing proof of what a husband most Desire [sic] to Know that his wife Loves him."  Washington Morton fit the economic expectations of the Schuylers, but his irreverent sense of humor & flippant behavior diminished his worthiness in Philip’s eyes. Washington Morton fit the economic expectations of the Schuylers, but his irreverent sense of humor & flippant behavior diminished his worthiness in Philip’s eyes. This description is hyperbole, since Cornelia more likely snuck out a door than leapt out a window. It is possible that Angelica gave her young sister advice or even direct aid with her elopement. Angelica had recently returned from Europe and Morton wrote that they were married by the same Judge Sedgwick who had married Angelica to John Barker Church. Philip forgave Cornelia quite quickly, but never really found a place in his heart Morton, who became Schuyler’s least favorite in-law. Philip wrote to his son of Morton: Washington Morton fit the economic expectations of the Schuylers, but his irreverent sense of humor & flippant behavior diminished his worthiness in Philip’s eyes. "his conduct, whilst here has been as usual, most preposterous. Seldom an evening at home, and seldom even at dinner - I have not thought it prudent to say the least word to him[...]as advice on such an irregular character is thrown away." Young Caty did better in Schuyler’s estimation, but her marriage was also an elopement. She married attorney Samuel Bayard Malcolm not long after her mother’s death in March of 1803. However, given descriptions of the big reveal, it is likely that the couple has already married, but Catharine’s death prevented Caty from being able to tell her father. Schuyler accepted Malcolm soon after, so when Schuyler died the next year, Caty would have had a clean conscience. Unfortunately, Malcolm died in 1817. So as not to remain a powerless widow, Caty remarried in 1822 to James Cochran, a prominent attorney and politician who was the son of Washington’s personal physician. Cochran was also her first cousin. Marrying a cousin was seen as a safe match, particularly for widows and widowers, as it consolidated wealth amongst family and one could trust that one’s children would be accepted since the new spouse was kin.  The Schuyler women had birthing rates similar to the averages for their time period. Margaret and Cornelia Schuyler died young (42, and 32 respectively). Caty's reflect two marriages, as her first husband died while she was still of child-birthing age. The Schuyler women had birthing rates similar to the averages for their time period. Margaret and Cornelia Schuyler died young (42, and 32 respectively). Caty's reflect two marriages, as her first husband died while she was still of child-birthing age. The Schuyler women had birthing rates similar to the averages for their time period. Margaret and Cornelia Schuyler died young (42, and 32 respectively). Caty's reflect two marriages, as her first husband died while she was still of child-birthing age. For women, a marriage contract provided necessary economic stability. Spending too long outside of the contract resulted in a lack of security for oneself and one’s family. By marrying well, men could also gain economic ground and benefit from the production of heirs. A woman could have a lot of influence on the early education of these heirs since she was the main caretaker until a child was old enough to go outside the home. For women, childrearing was an all-consuming part of their life after marriage. On average, women in the mid to late 18th century gave birth once every other year from her marriage until death or menopause, whichever came first. Infant mortality rates were high, with approximately half of children dying before reaching the age of 3. Even with this mortality rate, birthrates still averaged eight surviving children per mother! Towards the end of the century, women began having fewer births with slightly lower infant mortality rates – averaging 6 surviving children per mother. Catharine Schuyler fit these averages. According to the family bible, Catharine gave birth to fifteen children. Eight survived to adulthood. Her last child came when she was 47 years old. In other ways, Catharine was unusual - among the seven children who didn’t survive infancy, there was one set of twins and one set of triplets. Multiple births were rare, and the fact that Catharine survived those dangerous births was a testament to her health. As one can imagine this pattern was both physically and emotionally devastating for women. The majority of their lives were spent being pregnant, recovering from pregnancy, and taking care of young children, many of whom did not survive. Throughout this cycle, the Schuyler women were also managing the household and the social affairs of the family. Catharine thrived as a manager and Philip seemed to put a great deal of trust in her logistic abilities. She made purchases for the home, received orders, and was responsible for decisions concerning the estate in Schuyler’s absence. Aided by Schuyler’s military mentor John Bradstreet, she also acted as overseer for the initial construction of Schuyler Mansion while her husband was on business in England.  Schuyler Mansion once had 125 total acres with 80 acres of farmland and a series of back working buildings. Catharine was often placed in charge of the property in Schuyler's absence and managed the slaves who worked in the household. Schuyler Mansion once had 125 total acres with 80 acres of farmland and a series of back working buildings. Catharine was often placed in charge of the property in Schuyler's absence and managed the slaves who worked in the household. Schuyler Mansion once had 125 total acres with 80 acres of farmland and a series of back working buildings. Catharine was often placed in charge of the property in Schuyler's absence and managed the slaves who worked in the household. While attending to business, political, and military affairs, men were not home to prepare for or entertain high caliber guests whose support was often needed to maintain said business, political and military affairs. It fell on Catharine and the girls to foster a social atmosphere for their home. They threw parties, called on other households, and were ready to receive unexpected visitors at any time – including, for instance, the more than twenty military visitors sent to the home when Burgoyne was taken “prisoner guest” after his surrender to General Gates at the Battle of Saratoga. Catharine also acted as an overseer for the unsung women of Schuyler Mansion – the enslaved servants. The head servant Prince, the enslaved women including Sylvia, Bess and Mary, and the children like Sylvia’s children Tom, Tally-ho, and Hanover, who helped serve within the home, all reported directly to Catharine. These women did the majority of labor within the home – cooking, cleaning, mending, laundry, acting as nannies when the girls travelled, and perhaps even producing the materials used for these tasks – like rendering soap and dipping candles. All this was done while raising their own families. Sources on the enslaved women of the Schuyler household are even sparser, of course, but we tell the stories we have and hope that we will someday know more. Documents do not always allow us to tell the full range of stories we would like to tell. Thankfully, the Schuyler women were accomplished. Though they did not always fit the ideals of their society perfectly, they made themselves a prominent part of it. They married well, managed their family’s social connections and households, and very importantly, raised children who valued history and valued preserving their family’s legacy. While there are many questions that we at Schuyler Mansion still wish to answer about these women, we are fortunate to have the sources to interpret their lives, not just during Women’s History Month, but year round. To get more stories about these women, visit Schuyler Mansion’s blog or visit Facebook for information on our upcoming “Women of Schuyler Mansion” focus tour. AuthorDanielle Funiciello has been a historic interpreter at Schuyler Mansion since 2012. She earned her MA in Public History from the University at Albany in 2013 and has been accepted into the PhD Program in History for Fall 2017. She will be writing her dissertation on Angelica Schuyler Church. |

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

May 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 info@hrmm.org Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |