History Blog

|

|

|

|

|

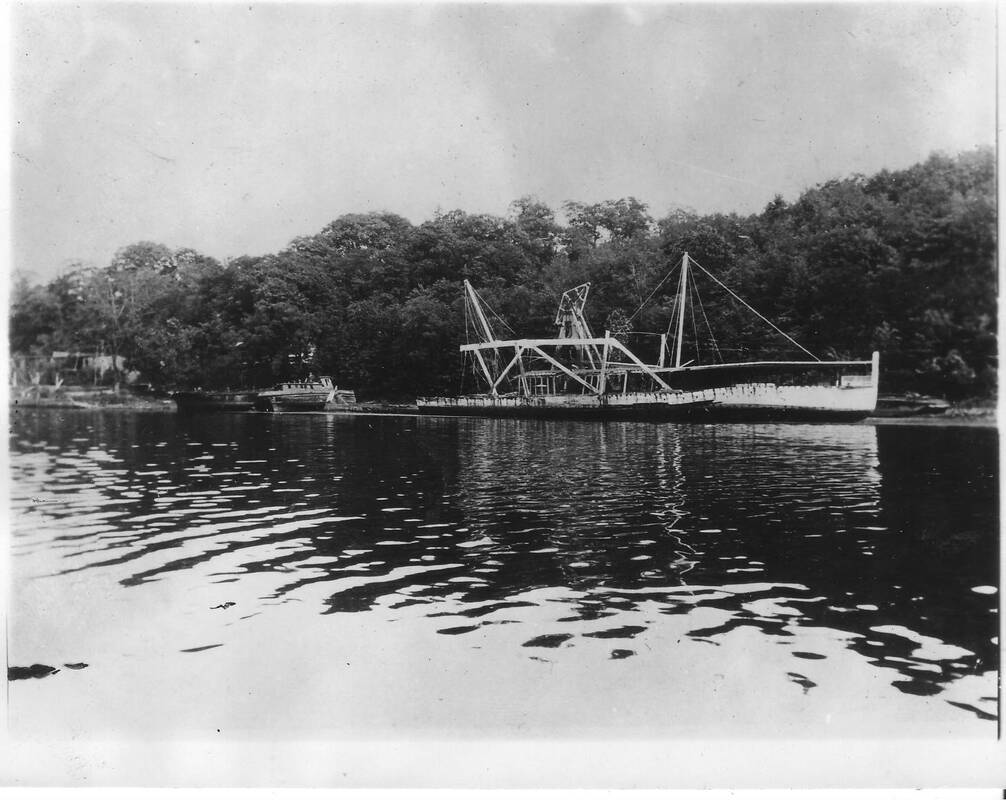

Editor’s Note: The following text is a verbatim transcription of an article featuring stories by Captain William O. Benson (1911-1986). Beginning in 1971, Benson, a retired tugboat captain, reminisced about his 40 years on the Hudson River in a regular column for the Kingston (NY) Freeman’s Sunday Tempo magazine. Captain Benson's articles were compiled and transcribed by HRMM volunteer Carl Mayer. See more of Captain Benson’s articles here. This article was originally published February 27, 1972. During the winter of 1920, both the “Mary Powell” and the “Albany” lay at the Sunflower Dock on Rondout at Sleightsburgh. The “Mary Powell” had been there since her last trip under her own power on Sept. 5, 1917. On Saturday, shortly before the ice went out of the creek, my brother Algot and I took my father’s lunch over to him on the “Albany” where he was working as a ship’s carpenter. Rumor was that just as soon as the ice broke up, the “Powell” would be towed to South Rondout to be broken up. Knowing this, my brother said, “Come on Bill, let’s take a walk over on the ‘Powell.’ It will probably be the last we ever be on her.” Cold and Dark We went aboard the gangway right aft of the engine room. All her fine machinery was black from the grease that had been put on the engine when she layed up so it would not rust. All steamboat engineers always coated the bright work with grease in this manner when their boat was laid up at the end of the season. Everything was cold and dark and still. When we went back to the dining room at the rear of the main deck. Most of the tables and chairs had already been removed. Everything was very dusty. Up on the saloon deck, most of the carpeting had been taken up, with a few pieces remaining here and there. A few of the big easy chairs in the saloon where still there but most were gone. Some of the plate glass windows were cracked, and others broken - with canvas tacked over the openings. When we went up on the hurricane deck, my brother had to use a screwdriver to pry open the door to the pilot house. It was jammed, probably due to the fact that the “Powell's” stern rested on the bottom at low tide. The east end of the dock had been filling in and hadn’t been dredged since the “Powell” stopped running. An Old Time Table In the pilot house, there was a long, low locker across the back. The top of the locker could be raised so that things like flags, pennants and pilot house supplies could be put inside. I found an old Catskill Evening Line time table, with a picture of the steamer “Clermont” on the cover, which I took with me. There were no chairs, since these had already been removed. The old side curtains on the pilot house windows were still in place. They would be pulled down on the side the sun would leaving Rondout on her flying trip to the metropolis to the south, or when the sun was going down behind the western hills on the up trip. The canvas that had covered her pilot house windows from the strong icy winds and snows, had been removed. The interior of the “Powell’s” pilot house was all varnished and it has turned very dark from the passing years and added coats of varnish. The big, hand steering wheel was only about half showing, most of the bottom half being concealed in a well in the deck. The top reached almost to the overhead of the pilot house. I noticed how the round turned spokes of the steering wheel were flattened out on both sides near the rim. I asked my brother what caused this. He said it came from the wear on the spokes caused by the pilot climbing the wheel like a ladder in order to turn the boat in a hurry. The old “Powell” never had a steam steering gear like the more modern steamboats. He Walked the Wheel “The pilot of the ‘Powell’ would have to climb the wheel coming into the Rondout Creek from the river on a flood tide,” Algot said. “When it is flood tide, there’s a very strong eddy at the mouth of the creek. The tide sets up strong and when it hits the south dike, it forms a half moon about 75 feet out from the south dike and then starts to set down. To keep steerage way on the ‘Powell’ the had to keep her hooked up until she entered the creek, because a side wheeler running slow or just drifting would have no rudder power. So the pilot in order to get the rudder hard over to port or starboard in a hurry would have to walk right up the steering wheel.” Algot, who had been quartermaster on the “Mary Powell” in her last years, pointed out that when the pilot got the steering wheel hard over he would then put the becket on the wheel to hold it. When the becket was taken off, the wheel would spin right back to midships. He added with a smile, “At times like that, the fatter and heavier the pilot, the easier the job.” Algot went on to point out to me the same act of walking up the steering wheel would take place on going around West Point and Anthony’s Nose and rounding up in New York harbor. In those long ago days when going down through the harbor on an ebb tide, a pilot had to get around very quick and find a hole in the heavy steamboat, tugboat, ferryboat and steamship traffic. On a steamboat like the “Mary Powell” with a hand steering gear, when going up or down through New York harbor, the pilot house was always fully manned. The captain or first pilot would be at the steering wheel, the second pilot standing with his hands on the bell pulls to the engine room or ready to grab the whistle cord, and the quartermaster as lookout on the forepeak.  The mostly dismantled "Mary Powell" at Connelly, c. 1925. Her walking beam engine and the forward hogging trusses are still visible, but the pilot house and upper decks have been removed, and nearly the entire back half of the vessel is gone to the waterline. Donald C. Ringwald Collection, Hudson River Maritime Museum. Leaving Their Marks Later in life when I saw the hand steering wheels of the “Jacob H. Tremper” and the steamer “Newburgh” of the Central Hudson Line, the spokes were all worn down and loose the same way. It showed how former pilots and captains left their marks on their steamboats long after they were gone. We left the old Queen of the Hudson after out farewell visit in the bright sunshine of the late winter afternoon. On April 20, she was towed by the tug “Rob” on her final trip to South Rondout where she was dismantled. AuthorCaptain William Odell Benson was a life-long resident of Sleightsburgh, N.Y., where he was born on March 17, 1911, the son of the late Albert and Ida Olson Benson. He served as captain of Callanan Company tugs including Peter Callanan, and Callanan No. 1 and was an early member of the Hudson River Maritime Museum. He retained, and shared, lifelong memories of incidents and anecdotes along the Hudson River. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 [email protected] Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |