History Blog

|

|

|

|

|

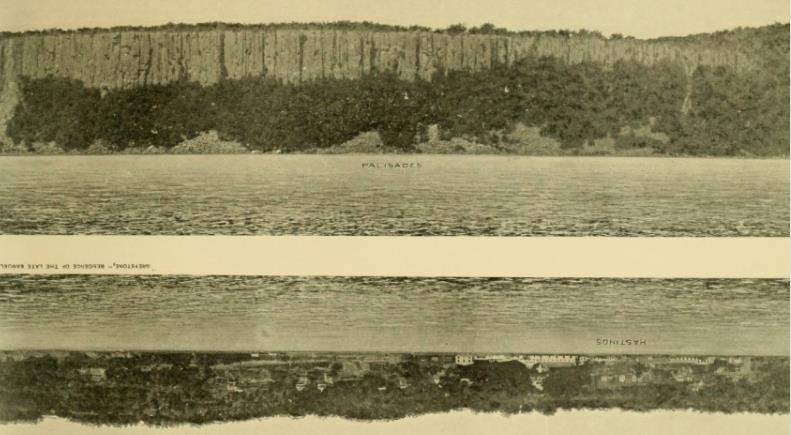

During the summer of 1884, Black veterans of the Civil War gathered on piers in Manhattan and what was then the independent city of Brooklyn. The steamboat John Lenox pulled up, towing a barge, and soldiers who served in a battalion named for abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison climbed aboard along with their families. This flotilla steamed through the New York Harbor and up the Hudson River, landing at a spot on the New Jersey banks that was called Excelsior Grove.[1] The veterans could spend the day swimming, hiking towards the Palisades rock formations that towered above, picking pimpernel flowers and wild strawberries, resting in the shade under oak and tulip trees, and listening to music.[2] Chatting with former comrades in arms and practicing military drills, Black soldiers remembered fighting in the battles that ended slavery.[3] This was one of many “excursions” to give city people without much spare change the chance to escape for a day from their dense and crowded urban neighborhoods. Getting out of the city was more than a matter of relaxation and recreation during this era, when most believed that bad smells were what made them sick.[4] Urban sanitation systems had not caught up with the rising population and rank odors wafted from overflowing outhouses and piles of uncollected garbage that festered in the streets.[5] On the decks of steamboats and in leafy waterfront groves, city people breathed deeply, hoping that the fresh air would fortify their weary bodies. At least sixty-nine lush excursion destinations with cool breezes, refreshing shade, and gorgeous views opened within a forty-nine mile radius of lower Manhattan between 1865 and 1900. This map shows the approximate locations of excursion groves that I have found. Everyone who lived in the densest, most impoverished, and least sanitary parts of the city yearned for a change of air and scenery, but excursions were especially meaningful to Black New Yorkers during the tense Reconstruction Era. While people of African descent were working to transform emancipation into an opportunity to finally secure full political and social equality, white neighbors adapted white supremacy for a nation without slavery. In New York, Black people faced harassment by the police, severe economic discrimination, and violence at the polls.[6] Intimidation and threats met them in the city’s parks, where they tried to claim their equal right to public space.[7] “Sable soldiers” were “drilling (in the dark) in one of our public squares,” reported the New York Herald in 1867. It was not safe to display Black “martial glory” in the parks except under the protective cover of nightfall because many white men considered military service to be their exclusive honor.[8] But outside the city in places like Excelsior Grove, soldiers like those who served in the William Lloyd Garrison Post No. 107 could wear their uniforms with pride, in safety. On chartered steamboats and in privately rented groves, Black New Yorkers could enjoy blooming landscapes together, away from the judgmental eyes and clenched white fists that greeted them whenever they went outdoors in the city. Excursions offered Black people the chance to breathe—and not just the fresh air that was scarce in Manhattan.  Excursionists came from one of the densest and most polluted spots on the planet to experience this scenery near Dudley’s Grove on the New York side of the Hudson and Excelsior and Alpine Groves on the New Jersey banks. Wallace Bruce, Panorama of the Hudson (New York: Bryant Union Publishing Co., 1906) New Yorkers of African descent were able to access these getaways starting in the 1870s because at least some white owners of steamboats and groves would accommodate any party with money to spend. These entrepreneurs got rich as excursionists bought cheap refreshments and pooled their pennies to rent the leafy grounds and the flotillas that carried them there. Orville Dudley was one of the businessmen whose eagerness for profit outweighed his racism when he decided whether or not to rent his grove in Hastings-on-Hudson to city people of African descent. A Black social club called the Green Horns visited Dudley’s Grove in August of 1870 and the Bethel African Church arrived the following summer. Dudley used the worst racist slur to describe these excursionists in his recordkeeping book. He called one party “a mean lot” and wrote of the other, “rough don't want them again.”[9] But Dudley loved money and Black people from the city had it, so he continued renting the grove to their excursion parties.[10] By the 1880s, Black churches, militia companies, and mutual aid associations visited destinations owned by other entrepreneurs too, like Excelsior and Riverside Groves and Iona Island.[11] Excursions opened a previously closed window for Black New Yorkers eager to get out of doors and out of the city. During the early nineteenth century, people of African descent were not welcome to join white patrons who gazed at flowers, ate ice cream, and sipped alcohol in the shade at commercial “pleasure gardens” in what was then the outskirts of New York.[12] Black entrepreneurs tried to open their own gardens in the 1820s, but faced racism on top of the usual business risks of bad weather and fire. The police ordered the closure of one of the gardens, while three others lasted for just one summer.[13] Near mid-century, beer gardens began opening in forested spots of upper Manhattan, but German American proprietors kept people of African descent out, decorated the grounds with racist imagery, and hosted offensive minstrel shows, where white actors with darkened skin performed gross stereotypes. By excluding and ridiculing people of African descent, these immigrant entrepreneurs—who themselves faced bias and prejudice in a nativist society—shored up their own access to white privilege.[14] After the turn of the century, amusement parks like Coney Island often had segregated facilities and were full of racist games like “African Dodger” and “Kill the Coon,” which beckoned visitors to throw balls at the heads of employees who were either Black or wearing blackface.[15] But between the eras of commercial gardens and amusement parks, steamboat excursions offered Black New Yorkers a rare chance to escape from the city with safety and dignity. In green refuges along the Hudson, Black residents of the metropolitan area strengthened social and political ties. New York’s Black community was growing at a rate more than double that of the white population in the 1870s, fueled in part by migrants fleeing white terrorism in the South.[16] But white supremacy shaped northern cities too, so Black New Yorkers who could not count on equal access to goods and services created their own institutions to care for one another, fundraising for these efforts by holding excursions. The Good Samaritan Home Association, for example, financed mutual aid work by selling fifty-cent tickets for an excursion to Dudley’s Grove. Funds raised at this grove also supported the Progressive American, an autonomous Black newspaper that offered a counter voice to the white supremacist media of the time.[17] Excursions for churches, militia companies, and social clubs stopped in New York and Brooklyn, uniting newcomers with longtime residents of both cities to build a metropolitan Black community.[18] Excursions forged connections between people of African descent at an important political turning point. Municipal leaders had rarely considered people of African descent as constituents before the Fourteenth Amendment made Black Americans citizens in 1868 and then the 1870 ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment promised all male citizens the right to vote.[19] Excursions helped consolidate the Black community as unprecedented access to the ballot box presented new opportunities to shape urban politics. Excursions were further politicized because Black leisure was controversial in a society rooted in slavery. Myths that people of African descent were devious, sneaky, and born to work circulated widely to justify an institution that relied on surveillance, control, and forced labor. During the Reconstruction Era, Black Americans who seized chances to leisure resisted the ideology that had rationalized slavery. By going on excursions, Black residents of New York, Boston, Wilmington, and Washington, D.C. insisted that they were deserving of pleasure, relaxation, comfort, and ease.[20] Whites responded by doubling down on the trope that people of African descent were dangerous when left to their own devices.[21] Along with racist images, stories, and performances, newspaper coverage of excursions made the case against Black leisure. Black excursions rarely made the news unless something went wrong.[22] Plenty of excursions passed peacefully, but white readers eagerly consumed sensationalized news of violence. The New York Times cast an 1887 Good Samaritan Home excursion as a scene of chaos, where “the razor went flashing through the air, the beer mug rose on high, a cane whirred overhead, and then the blood flowed.”[23] A score of other papers published their own accounts of the damage wrought by these “Implements of War” as the steamboat chugged away from Dudley’s Grove, back towards the city.[24] But this “riot lasted” for only ten minutes, admitted the Times, while the Tribune called the event “almost a riot,” rather than a full blown rebellion.[25] Newspapers exaggerated scuffles on excursions for white readers ready to believe that people of African descent had violent tendencies.[26] As Black excursionists left urban hardships behind, racist ideology followed in their wake. Despite biased coverage, excursions offered Black residents of the metropolitan area some respite from the intense racism that they experienced in daily life. Boarding steamboats with members of their growing community, excursionists traded provocations by white neighbors and harassment by the police on dusty and filthy urban streets for verdant views, salty breezes, and the dignity of autonomous Black spaces. Excursions posed a stark contrast to Manhattan, both in terms of environment and atmosphere. For Black people navigating white supremacy in a dense, polluted, and divided city, the Hudson River was a pathway towards relief that was all too brief. ENDNOTES: [1] “Fight at a Picnic,” New York Times, August 29, 1884, 5. [2] Details of Excelsior Grove’s environment come from “The Children’s Excursions,” New York Times, June 23, 1873, 8. [3] On veterans getaways, see C. Ian Stevenson, Vacationing with the Civil War: Maine’s Regimental Summer Cottages,” Civil War History 63, no. 2 (June 2017): pp. 151-180. [4] For the perceived ill effects of bad smells on health, see Melanie A. Kiechle, Smell Detectives: An Olfactory History of Nineteenth-Century Urban America (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2017). [5] Martin V. Melosi, Garbage in the Cities: Refuse, Reform, and the Environment (Homewood, IL: Dorsey Press, 1981); David Stradling, The Nature of New York: An Environmental History of the Empire State (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2010). [6] David Quigley, “Acts of Enforcement: The New York City Election of 1870,” New York History 83, no. 3 (Summer 2002): 271-292; Craig Steven Wilder, In the Company of Black Men: The African Influence on African American Culture in New York City (New York: New York University Press, 2001); Khalil Gibran Muhammad, The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2010). [7] For police harassment of Black parkgoers, see “One Policeman’s Deserts,” New York Herald, July 3, 1891, 9. [8] “A Negro Regiment” New York Herald, August 26, 1867, 7. For white opposition to Black soldiers during the Civil War, see Eric Foner, The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2010), 202, 214-215, 250-251. [9] Orville Dewey Dudley’s Daybook for Dudley’s Grove, Hastings Historical Society, Hastings-on-Hudson, August 22, 1870, August 10, 1871. [10] “Boss Tweed’s Butler Robbed,” September 15, 1872, 10; “Westchester County,” New York Times, September 14, 1879, 5; “Arraigned on the Charge of Murder,” New York Times, September 25, 1877, 8. [11] “A Colored Lad’s Suicide, New York Times, July 9, 1885, 2; “A Negro Picnic,” The Auburn, July 22, 1887, 1; “Bound for Riverside Grove,” Brooklyn Daily Standard Union, August 16, 1888, 2; “They Had a Nice Time,” New York Times, July 27, 1888, 5. [12] “Vauxhall Garden,” New-York American for the Country, May 4, 1826, 2. [13] “African Amusements,” National Advocate, September 21, 1821, 2; Marvin McAllister, White People Do Not Know How to Behave at Entertainments Designed for Ladies & Gentlemen of Colour: William Brown’s African and American Theater (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2003); “NICHOLAS PIERSON,” Freedom’s Journal, June 8, 1827; “MEAD GARDEN,” Freedom’s Journal, April 28, 1828. [14] For the transformation of European immigrants from racial others to privileged whites, see Noel Ignatiev, How the Irish became White (New York: Routledge, 1995); Thomas A. Guglielmo, White on Arrival: Italians, Race, Color, and Power in Chicago, 1890-1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004). [15] David E. Goldberg, The Retreats of Reconstruction: Race, Leisure, and the Politics of Segregation at the New Jersey Shore, 1865-1920 (New York: Fordham University Press, 2017), 3-9; “Gambling at North Beach,” New York Times, August 2, 1897, 1; Jon Sterngass, First Resorts: Pursuing Pleasure at Saratoga Springs, Newport & Coney Island (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001), 105. Kara Schlicting recovers a Black entrepreneur’s many efforts to establish an amusement park in the East River and on the Long Island Sound for people of African descent, but racism blocked him at every turn. Kara Murphy Schlicting, New York Recentered: Building the Metropolis from the Shore (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019). [16] Graham Russell Hodges, Root & Branch: African Americans in New York & East Jersey, 1613-1863 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999), 270. [17] “Boss Tweed’s Butler Robbed,” September 15, 1872, 10; “Westchester County,” New York Times, September 14, 1879, 5; “Arraigned on the Charge of Murder,” New York Times, September 25, 1877, 8. [18] “A Negro Picnic,” The Auburn, July 22, 1887, 1. [19] When New York State legislators enacted universal male suffrage in 1821, they added a qualification that required Black men to own a large amount of property in order to access the ballot. By 1840, only 90 Black men could vote out. Leslie M. Harris, In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626-1863 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 118-119; Leslie M. Alexander, African or American? Black Identity and Political Activism in New York City, 1784-1861 (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2008), 103. [20] Andrew Kahrl, “‘The Slightest Semblance of Unruliness’: Steamboat Excursions, Pleasure Resorts, and the Emergence of Segregation Culture on the Potomac River,” Journal of American History 94, No. 4 (March 2008), 1109-1110, 1134, 1121, 1123. [21] David R. Roediger, The Wages of Whiteness: Race and the Making of the American Working Class (London: Verso, 1991), 167-180. [22] For accounts of “riots” on Black excursions, see “Colored Picnicker in a Row: Charges of Theft Almost as Numerous as Blows,” New York Times, August 23, 1895, 2; “An Excursion Lands for Police,” New-York Tribune, July 28, 1899, 8; “Riot at a Negro Picnic: Several Stabbed or Shot on a Barge,” New York Times, June 20, 1907, 8; “Fight at a Picnic,” New York Times, August 29, 1884, 5. [23] “Razors Flashing Fast,” New York Times, July 22, 1887, 5. [24] “A Negro Picnic: A Free Fight in which Razors, Beer Mugs and Clubs Play a Promiscuous Part,” The Auburn, July 22, 1887, 1; “Razor and Beer Mugs: Implements of War Used by Colored Excursionists,” Syracuse Weekly Express, July 27, 1887, 6. [25] “Almost a Riot on an Excursion Barge,” New-York Tribune, July 22, 1887, 5. [26] Historian Andrew Kahrl analyzes negative portrayals of Black excursions from Washington, D.C. to a destination that the press called “Razor Beach” in the late nineteenth century. Biased and inaccurate reporting led to increased policing of the waterfront and an unjust targeting of people of African descent. Kahrl, “The Slightest Semblance of Unruliness,” 1121, 1136, 1119, 1122-1126. AuthorMarika Plater is a PhD Candidate in History at Rutgers University who studies environmental inequality in nineteenth century New York City. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 [email protected] Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |