History Blog

|

|

|

|

|

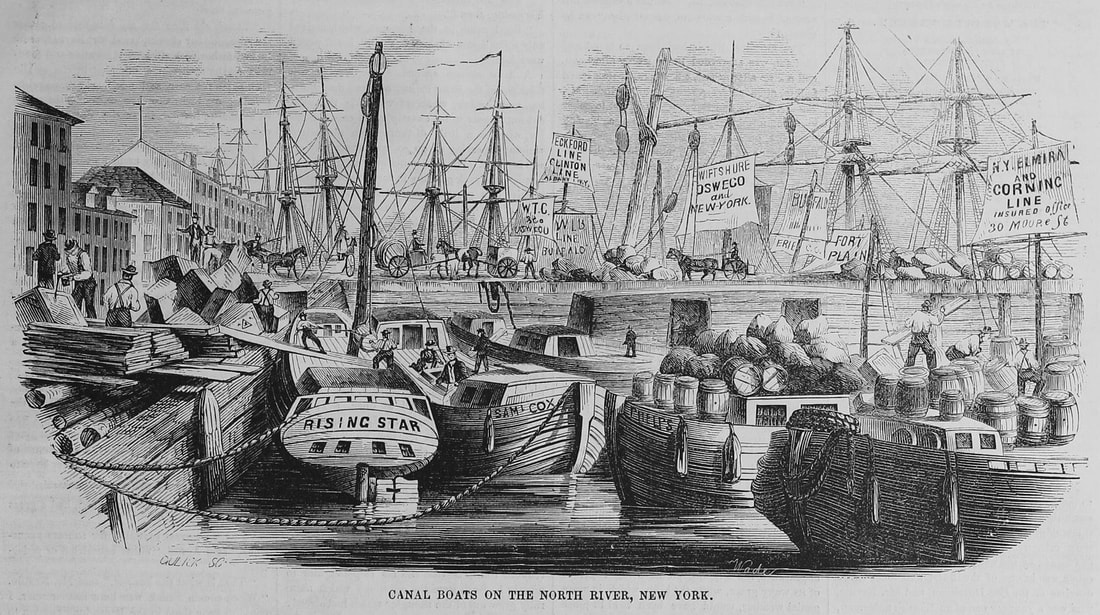

Editor's note: The following excerpts are from the January 3, 1875 issue of the "New York Times". Thank you to Contributing Scholar George A. Thompson for finding and cataloging this article. The language, spelling and grammar of the article reflects the time period when it was written. Loading Her Up. Scenes on the Docks. The Shipping Clerk – The Freight – The Canal-Boat Children. I am seeking information in regard to the late 'longshoremen's strike, and am directed to a certain stevedore. I walk down one of the longest piers on the East River. The wind comes tearing up the river, cold and piercing, and the laboring hands, especially the colored people, who have nothing to do for the nonce, get behind boxes of goods, to keep off the blast, and shiver there. It was damp and foggy a day or so ago, and careful skippers this afternoon have loosened all their light sails, and the canvas flaps and snaps aloft from many a mast-head. I find my stevedore engaged in loading a three-masted schooner, bound for Florida. He imparts to me very little information, and that scarcely of a novel character. "It's busted is the strike," he says. "It was a dreadful stupid business. Men are working now at thirty cents, and glad to get it. It ain't wrong to get all the money you kin for a job, but it's dumb to try putting on the screws at the wrong time. If they had struck in the Spring, when things was being shoved, when the wharves was chock full of sugar and molasses a coming in, and cotton a going out, then there might have been some sense in it. Now the men won't never have a chance of bettering themselves for years. It never was a full-hearted kind of thing at the best. The boys hadn't their souls in it. 'Longshoremen hadn't like factory hands have, any grudge agin their bosses, the stevedore, like bricklayers or masons have on their builders or contractors. Some of the wiser of the hands got to understand that standing off and refusing to load ships was a telling on the trade of the City, and a hurting of the shipping firms along South street. The men was disappointed in course, but they have got over it much more cheerfuller than I thought they would. I never could tell you, Sir, what number of 'longshoremen is natives or aint natives, but I should say nine in ten comes from the old country. I don't want it to happen again, for it cost me a matter of $75, which I aint going to pick up again for many a month." I have gone below in the schooner's hold to have my talk with the stevedore, and now I get on deck again. A young gentleman is acting as receiving clerk, and I watch his movements, and get interested in the cargo of the schooner, which is coming in quite rapidly. The young man, if not surly, is at least uncommunicative. Perhaps it is his nature to be reticent when the thermometer is very low down. I am sure if I was to stay all day on the dock, with that bitter wind blowing, I would snap off the head of anybody who asked me a question which was not pure business. I manager, however, to get along without him. Though the weather is bitter cold, and I am chilled to the marrow, and I notice the young clerk's fingers are so stiff he can hardly sign for his freight, I quaff in my imagination a full beaker of iced soda, for I see discharged before me from numerous drays carboys of vitriol, barrels of soda, casks of bottles, a complicated apparatus for generating carbonic-acid gas – in fact, the whole plant of a soda-water factory. I do not quite as fully appreciate the usefulness of the next load which is dumped on the wharf – eight cases clothes-pins, three boxes wash-boards, one box clothes-wringers. Five crates of stoneware are unloaded, various barrels of mess beef and of coal-oil, and kegs of nails, cases of matches, and barrels of onions. At last there is a real hubbub as some four vans, drawn by lusty horses, drive up laden with brass boiler tubes for some Government steamer under repairs in a Southern navy-yard. The 'longshoremen loading the schooner chaff the drivers of the vans as Uncle Sam's men, and banter them, telling them "to lay hold with a will." The United States employees seem very little desirous of "laying hold with a will," and are superbly haughty and defiantly pompous, and do just as little toward unloading the vans as they possibly can thus standing on their dignity, and assuming a lofty demeanor, the boxes full of heavy brass tubes will not move of their own accord. All of a sudden a dapper little official, fully assuming the dash and elan of the navy, by himself seizes hold of a box with a loading-hook; but having assert himself, and represented his arm of the service, having too scratched his hand slightly with a splinter on one of the boxes, he suddenly subsides and looks on quite composedly while the stevedore and 'longshoreman do all the work. Now I am interested in a wonderful-looking man, in a fur cap, who stalks majestically along the wharf. Certainly he owns, in his own right the half-dozen craft moored alongside of the slip. He has a solemn look, as he lifts one leg over the bulwark of a schooner just in from South America, and gets on board of her. He produces, from a capacious pockets, a canvas bag, with U.S. on it, and draws from it numerous padlocks and a bunch of keys. He is a Custom-house officer. He singles out a padlock, inserts it into a hasp on the end of an iron bar, which secures the after-hatch, snaps it to, gives a long breath which steams in the frosty air, and then proceeds, with solemn mein, to perform the same operation on the forward hatch. Unfortunately, the Government padlock will not fit, and, being a corpulent man, he gets very red in the face as he fumbles and bothers over it. Evidently he does not know what to do. He seems very woebegone and wretched about it, as the cold metal of the iron fastening makes it uncomfortable to handle. Evidently there is some block in the routine, on account of that padlock, furnished by the United States, not adapting itself to the iron fastenings of all hatches. He goes away at last, with a wearied and disconsolate look, evidently agitating in his mind the feasibility of addressing a paper to the Collector of the Port, who is to recommend to Congress the urgency of passing measures enforcing, under due pains and penalties, certain regulations prescribing the exact size of hatch-fastenings on vessels sailing under the United States flag.  "Canal Boats on the North River, New York" by Wade, "Gleason's Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion," December 25, 1852. Note the sail-like signs for various towing lines and destinations, as well as the jumble of lumber and cargo boxes on the pier at left, waiting to be loaded onto the canal boats (or vice versa). I return to my schooner. By this time the wharf is littered with bales of hay, all going to Florida. I wonder whether it is true, as has been asserted, that the hay crop is worth more to the United States than cotton? I think, though, if cotton is king, hay is queen. Now comes an immense case, readily recognized as a piano. I do not sympathize with this instrument. Its destination is somewhere on the St. John's River. Now, evidently the hard mechanical notes of a Steinway or a Chickering must be out of place if resounding through orange groves. A better appreciation of music fitting the locality would have made shipments of mandolins, rechecks, and guitars. Freight drops off now, and comes scattering in with boxes of catsup, canned fruits, and starch. Right on the other side of the dock there is a canal-boat. She has probably brought in her last cargo. And will go over to Brooklyn, where she will stay until navigation opens in the Spring. There is a little curl of smoke coming from the cabin, and presently I see two tiny children – a boy and a girl – look through the minute window of the boat, and they nod their heads and clap their hands in the direction of the shipping clerk. The boy looks lusty and full of health, but the little girl is evidently ailing, for she has her little head bound up in a handkerchief, and she holds her face on one side, as if in pain. The little girl has a pair of scissors, and she cuts in paper a continuous row of gentlemen and ladies, all joining hands in the happiest way, and she sticks them up in the window. This ornamentation, though not lavish, extends quite across the two windows, the cabin is so small. Having a decided fancy, a latent talent, for making cut-paper figures myself, I am quite interested, as is the receiving clerk. I twist up, as well as my very cold fingers will allow, a rooster and a cock-boat out of a piece of paper, and I place them on a post, ballasting my productions with little stones, so that they should not blow away. The children are instantly attracted, and the little boy, a mere baby, stretches out his hands. My attention is called to a dray full of boxes, which are deposited on the wharf for our schooner. Somehow or other the receiving clerk, without my asking him, tells me of his own accord what they contain – camp-stools. I can understand the use of camp-stools in Florida: how the feeble steps of the invalid must be watched, and how, with the first inhalation of the sweet balmy air, bringing life once more to those dear to us, some loving hand must be nigh, to offer promptly rest after fatigue. I return to my post, but alas my rooster and cock-boat have been blown overboard; the wind was too much for them. I kiss my hand to the little girl, who smiles with only one-half of her face; the stiff neck on the other side prevents it. The little boy points to the post and makes signs for more cock-boats. Snow there happens to come along on that wharf an ambulant dealer with a basket containing an immense variety of the most useless articles. He has some of the commonest toys imaginable, selected probably for the meagre purses of those who raise up children on shipboard. There are wooden soldiers, with very round heads but generally irate expressions, and small horses, blood-red, with tow tails and wooden flower-post, with a tuft of blue moss, from which one extraordinary rose blossoms, without a leaf or a thorn on the stem. On that post for ten cents that ambulant toy man put five distinct object of happiness, when the shipping clerk interfered. "It's a swindle, Jacob," he said. That young man was certainly posted in the toy market along the wharves. "You ain't going to sell those things two cents a piece, when they are only a penny? You must be wanting to retire after first of the year. Bring out five more of them things. Three more flower-pots and two more horses. The little girl takes the odd one. What's this doll worth? Ten cents! Give you five. Hand it over. Now clear out. I see you, Sir, watching them children. Poor little mites. No mother, Sir. Father decent kind of fellow; says their ma died this Spring. Has to bring 'em up himself, and is forced to leave them most all day. He is only a deck-hand and will be the boat-keeper during Winter. Been noticing them babies ever since I have been loading the schooner – most a week – and been a wanting to do something for their New-Year's. A case of mixed candies busted yesterday, and they got some. They have been at the window ever since, expecting more; but nothing busted. You can't get in; the cabin is locked, but I can manage it through the window." So my young friend climbed on board, with the toys in his pocket, lifted up the sash, and passed through the toys one by one, the especial rights of proprietorship having been carefully enjoined. Presently all the soldiers and the follower-pots were stuck in the window, and the little girl was hugging the doll. "Loading her up; taking in freight for a vessel of a Winter's day on a wharf isn't fun," said the young gentlemen sententiously. "I shouldn't think it was," I replied. "In fact, there ain't much of anything to see or do on a wharf which is interesting to a stranger." "You are from the country, ain't you?" asked the young man with a smile. "Never seen New-York before? Wish you a happy New Year, anyhow." I did not exactly how there could be any reservation as to wishing me a happy New Year whether I was from the country or not, but supposing that this singularity of expression arose from the general character of the young man, or because he was uncomfortable from the frosty weather, I returned the compliment, inquiring "whether a stiff neck was not very hard on children," and not being a family man, added, "They all get it sometimes, and get over it, don't they ?" "It ain't a stiff neck, it's mumps. Mother sent me a bottle of stuff for the child three days ago, and her father has been rubbing it on, and she's most over it now. When I was a little boy," added the clerk reflectively, "toys cured most everything as was the matter with me." "Just my case," I replied, as we shook hands and I left the wharf. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 [email protected] Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |