History Blog

|

|

|

|

|

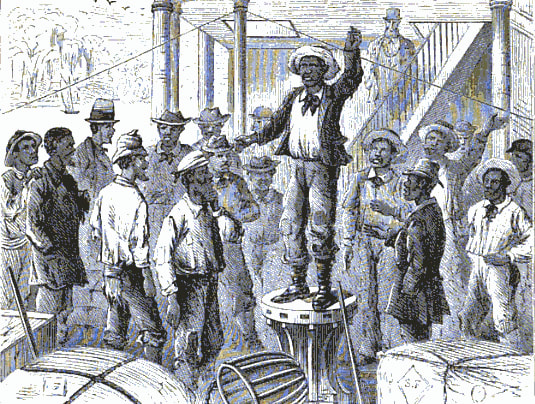

You may have seen sea shanties in the news lately. CNN has talked about them. And NPR. Our friends at SeaHistory did a lovely writeup, too. For some reason, these historic maritime songs have struck a chord with folks around the world. Shanties may have started their modern revival with the 2019 film, Fishermen's Friends, based on a true story about a group of Cornish fishermen whose work song chorus catapulted them to unexpected stardom in the UK. The film became available to American audiences via streaming giant Netflix in 2020. Sea songs and shanties are two different things, according to experts interviewed by JSTOR daily and Insider.com. Shanties are work songs, often designed for call-and-response. Sea songs are those about the sea, but not designed to be sung while at work. Both evoke a bygone era the lends itself to romanticism, even as the real life experience was less than ideal. "The Wellerman" and ShantytokSo why "The Wellerman" and why did Shantytok become a thing? Scottish postal worker Nathan Evans (he's since quit his job with a record deal in hand) posted a video of his acapella version of "The Wellerman," a 19th century New Zealand whaling song to TikTok with the hashtag #seashanty on December 27, 2020. Kept home by the pandemic lockdown, along with many other people around the world, Evans' version went viral. The next day, Philadelphia teenager Luke Taylor used TikTok's duet feature to add a harmonizing bass line to Evans' video. That version, too, went viral, and other TikTok users from around the world kept adding harmonies and instrumentals to build on Evans' original song. "The Wellerman," also known as "Soon May the Wellerman Come," is a song based in real life. Joseph Weller was a wealthy Englishman suffering from tuberculosis. A doctor recommended a sea voyage, and Weller and his family found their way to Australia in 1830. The next year, they purchased a barque and established a whaling station in nearby New Zealand - likely without the permission of the local Maori, who raided the station several times. The Wellers persisted until Joseph died in 1834. His sons continued whaling for several years, but sold out in 1840 and returned to Sydney. In later years the station also doubled as a general store supplying other whaling ships as well as their own. When the Wellers sold out, the station continued as a general store. So from the chorus of the song the lines, "Soon may the Wellerman come and bring us sugar and tea and rum" are likely a direct reference to the Weller family store supplying whaling ships. Read more about the history of "The Wellerman" and a biography of the Wellers. Unlike the sort of whaling practiced in Nantucket and made famous by Moby Dick (fun fact - Herman Melville actually worked on a Weller whaling ship), whaling in New Zealand in the 1830s was done from shore and was developed in response to declining sperm whale populations (learn more about shore-based whaling). Maori people in New Zealand also practiced whaling, and the crews of whaling vessels and stations were likely racially and ethnically diverse. Edward Weller himself married a Maori woman (learn more about Maori whaling traditions and the Weller connection). "The Wellerman" LyricsThe above version of "The Wellerman" is by the Irish Rovers and was filmed in 1977 aboard a sailing ship off of New Zealand. 1. There was a ship that put to sea, The name of the ship was the Billy of Tea The winds blew up, her bow dipped down, O blow, my bully boys, blow. Chorus: Soon may the Wellerman come And bring us sugar and tea and rum. One day, when the tonguin' is done, We'll take our leave and go. 2. She had not been two weeks from shore When down on her a right whale bore. The captain called all hands and swore He'd take that whale in tow. 3. Before the boat had hit the water The whale's tail came up and caught her. All hands to the side, harpooned and fought her When she dived down below. 4. No line was cut, no whale was freed; The Captain's mind was not of greed, But he belonged to the whaleman's creed; She took the ship in tow. 5. For forty days, or even more, The line went slack, then tight once more. All boats were lost (there were only four) But still the whale did go. 6. As far as I've heard, the fight's still on; The line's not cut and the whale's not gone. The Wellerman makes his regular call To encourage the Captain, crew, and all. Shanty v. ChanteyYou may have seen it spelled "chantey" or "chanteys" before, based on the French word "chanter" meaning "to sing" or "chantez" meaning "Let's sing" (both pronounced "shawn-tay"). Although most dictionaries now agree that the "correct" spelling is "shanty," "chantey" has held on in many American communities. Perhaps to differentiate it from the waterfront shack also known as a "shanty?" (that word also derives from the French - this time the French-Canadian "chantier," meaning a lumber camp shack). Or perhaps because Americans are more likely to adopt foreign words wholesale into the lexicon. Any way you spell it, chantey, chanty, shanty, or shantey - all are technically correct. The African Connection ORIGINAL CAPTION: "At the bow of the boat were gathered the negro deck-hands, who were singing a parting song. A most picturesque group they formed, and worthy the graphic pencil of Johnson or Gerome. The leader, a stalwart negro, stood upon the capstan shouting the solo part of the song, the words of which I could not make out, although I drew very near; but they were answered by his companions in stentorian tones at first, and then, as the refrain of the song fell into the lower part of the register, the response was changed into a sad chant in mournful minor key." Illustration from “Down the Mississippi” by George Ward Nichols, Harper’s New Monthly Magazine 41 (246) (November 1870). Some have questioned whether the reference in "The Wellerman" to "bring us sugar and tea and rum" was a reference to slavery. But given that "The Wellerman" is set in New Zealand, it was far more likely that the reference was about delivering sailors' rations, rather than a direct connection to slavery. However, sea shanties do have a direct connection to Africa and slavery. Call and response style work songs were common in West Africa, where many people were captured and sold into slavery for hundreds of years. Enslaved people brought these work song traditions with them when they were forced into labor in the Americas. Slaves worked in fishing, on sailing ships, and even on steamboats. Slaves who loaded and unloaded steamboats often sang a style of work song that came to be known as "roustabout" songs. When combined with dance, this song style was known as "coonjine" (learn more). Singing was one way that enslaved people could push back against the brutal domination of enslavers. Some references even indicate that Black and enslaved people themselves were once called "chanteys," reflective of their singing talents. New York singer and historian Vienna Carroll (who we've featured before), has also helps preserve New York's Black maritime history through song. Her version of "Shallow Brown" recounts an enslaved man, Shallow Brown, being sold away from his wife to work on a whaling ship in the North. Whaling in particular offered opportunities for free Black sailors and whalers in the United States. As whaling shifted to the Pacific and the Arctic, Black mariners were able to escape the harsher racism of the Caribbean and the American South. You can learn more about enslaved and free Black mariners in a previous blog post by historian Craig Marin. As anyone who has ever tried to raise a sail knows, singing "Haul Away Joe" can help you work in tandem with others. Keeping a rhythm helps with hauling, rowing, pulling in nets, loading cargoes, and any other heavy task that requires more than one person to work in rhythm with another. Singing also keeps the mind occupied, but focused on the task at hand. The West African call-and-response style became integral to shanties and was quickly adopted and adapted by sailors of all ethnicities. Sources & Further ReadingShanties:

New Zealand Whaling and The Wellers:

Black Mariners and Shanties:

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 [email protected] Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |