History Blog

|

|

|

|

|

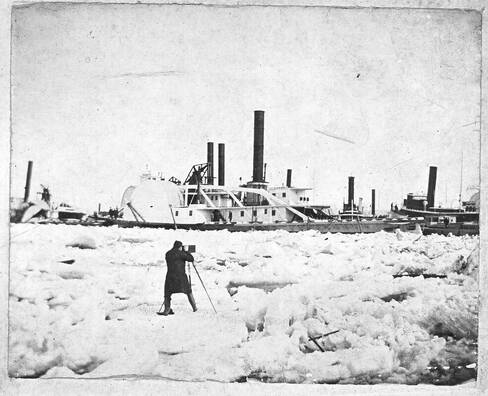

Editor’s Note: The following text is a verbatim transcription of an article featuring stories by Captain William O. Benson (1911-1986). Beginning in 1971, Benson, a retired tugboat captain, reminisced about his 40 years on the Hudson River in a regular column for the Kingston (NY) Freeman’s Sunday Tempo magazine. Captain Benson's articles were compiled and transcribed by HRMM volunteer Carl Mayer. See more of Captain Benson’s articles here. This article was originally published April 8, 1973.  Photographer capturing the Cornell Steamboat Company tug and towboat fleet after the freshet of 1893 washed the fleet out into the Hudson River. The freshet is a flood due to melting snow and rain. This one caused a late winter flood that broke an ice dam on the Rondout Creek and pushed the boats out into the Hudson River. Donald C. Ringwald Collection, Hudson River Maritime Museum The month of March has frequently been known for its capricious pranks of weather. On two occasions in particular —March 13, 1893 and March 12, 1936 — madcap March weather brought considerable excitement locally. On both dates, freshet conditions in Rondout Creek caused the ice covering the creek’s surface to go out with a rush, carrying everything in its path out towards the Hudson. On both occasions, the conditions were similar. The preceding winter months had been severe with heavy ice. During early March the weather turned warm causing runoffs from melting snow into the Wallkill River and upper Rondout Creek. Water and broken ice cascading over the dam at Eddyville backed up behind the solid creek ice creating considerable pressure. Finally, the solid ice below Eddyville began to crumble. Once the ice started to move, its movement accelerated rapidly, rushing down the creek with great force and speed. Anything in its path was swept along downstream. In both instances, this was mostly the fleet of the Cornell Steamboat Company. Those who witnessed the moving ice described it as an awesome sight. Mooring lines were snapped like strings. Vessels in the path of the grinding ice moved like ghosts down the creek and out into the Hudson River where they came to a stop in a jumbled mass against the solid ice of the river. In both instances, despite damage to the vessels involved, surprising there was only one reported personnel injury in 1893 and none in 1936. More Spectacular The freshet of 1893 was probably the more spectacular since more vessels were involved, including at least eight big side-wheel towboats. All told, approximately 50 vessels were swept out of the creek. In addition to the big side-wheel towboats, these included at least 15 Cornell tugboats and two dozen canal boats and barges. In 1893 melee of ice and boats set adrift occurred in the late afternoon on Monday, March 13. At about 4 p.m. a huge ice jam above Wilbur let go and the uncontrolled movement down Rondout Creek commenced. A Freeman reporter described the scene as follows: “It was a scene that will never be forgotten by those who witnessed the outgoing vessels, as they jammed against one another and against the docks, the noise of parting lines and cracking timbers being plainly heard a block or more away. The shouts of the men on the boats who like maniacs hauling in the lines, endeavoring to make the boats fast, and the cries of warning from people on the docks to the boatmen added to the excitement and the scene was one that words cannot picture.” At the time, the ferryboat ‘‘Transport’’ was coming across the river from Rhinecliff and was just inside the dikes of the creek when she was met by the outgoing ice and army of drifting vessels. She was enveloped by the advancing fleet and swept back into the river. Some of the ferry’s passengers were reported to have been panic stricken and to have leaped across floating blocks of ice to the solid ice of the Hudson. Apparently, they all successfully made it. Captain Injured The only reported injury was to Captain Charles Post of the Cornell tugboat “H. T. Caswell." His right foot was broken when caught between a mooring line and a cleat. A Dr. Smith and a Dr. Stern made their way across the ice in the river to the tugboat where they treated the injured boatman. He was later carried in a blanket across the ice to shore. In 1936 freshet was probably the more damaging since the Cornell tugs “Rob,” "Coe F. Young” and “William E. Cleary” were sunk and eight others fetched up along the south side of the creek opposite Ponckhockie, whereas in 1893 virtually all of the boats involved had floated out into the Hudson. The 1936 marine spectacular started at about 7:30 a.m. on Thursday, March 12. At that time, the ice started to move out of the creek below Eddyville and rapidly built up force and momentum as it moved toward the Hudson. As the ice surged past the C. Hiltebrant Shipyard at Connelly, it took along with it a small passenger steamboat, two tugboats, a derrick boat, and three or four barges and lighters that had been in winter quarters at the yard. Two scows tied up at Island Dock were swept away by the grinding ice and joined the growing armada of vessels moving downstream. The tug “Rob” had been tied up west of the Rhinecliff ferry slip on Ferry Street. A drifting barge caromed off the side of the “Rob,” heeled her over and sent her to the bottom of the creek. Eleven Cornell Tugboats that had been moored at Sleightsburgh all were set adrift by the advancing ice and started on their way down by the Rondout Creek. The Foggy Mark At the Cornell shops at Rondout, eleven out of twelve tugs tied up there were swept away. Snapping mooring lines sounded like guns going off. A heavy fog enveloped the area: and added to the ghostly appearance of the scene. At that point, some 30 tugs, barges and other vessels were moving down the creek and disappearing from sight into the foggy murk enveloping the creek and river. At the Sunflower dock at Sleightsburgh — further down creek — lay nine more Cornell tugboats and a steam derrick. The ice and moving vessels swept by these tugs and miraculously they remained in place. The outboard tug at the head of this group, however, the “Coe F. Young,” was holed and sunk and possibly this saved the remaining tugs from also moving along with the others. Two days later, the tug “William E. Cleary’’ — tied up with this group — rolled over and sank. When the fog lifted shortly before noon on March 12, eight of the tugboats that had been swept along from the neighboring Baisden shipyards at Sleightsburgh were strewn grounded along the south shore of the creek opposite the old Central Hudson gas house. All of the others were jumbled together out in the Hudson River off the Rondout lighthouse against the solid river ice. By a quirk of fate, the Cornell tugboat ‘‘J. C. Hartt” was the “hero” of both the 1893 and the 1936 freshets. In 1893 she was swept out into the Hudson and was one of the first tugs to get steam up and return the others to their berths. In 1936, after being set adrift, she moved down the creek stern first close along the Rondout docks. At Gill’s dock in Ponckhockie she hit a brick scow moored there. Ended Voyage The scow captain jumped aboard the “Hartt,’’ ran forward and was able to get a line ashore and end her unscheduled voyage at that point. Fortunately, at the time the “Hartt” was being made ready for the coming season. In short order, steam was raised on the tug and she soon was able to get underway and start the task of corralling the run-away fleet. By March 15, virtually all of the run-aways were back at their berths. The sunken “Rob” and “William E. Cleary” were subsequently raised. The sunken “Coe F. Young,” however, never was — and to this day what is left of the old tug is still on the bottom of Rondout Creek off the old Sunflower Dock where she met her end in the freshet of March 12, 1936. AuthorCaptain William Odell Benson was a life-long resident of Sleightsburgh, N.Y., where he was born on March 17, 1911, the son of the late Albert and Ida Olson Benson. He served as captain of Callanan Company tugs including Peter Callanan, and Callanan No. 1 and was an early member of the Hudson River Maritime Museum. He retained, and shared, lifelong memories of incidents and anecdotes along the Hudson River. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 [email protected] Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |