History Blog

|

|

|

|

|

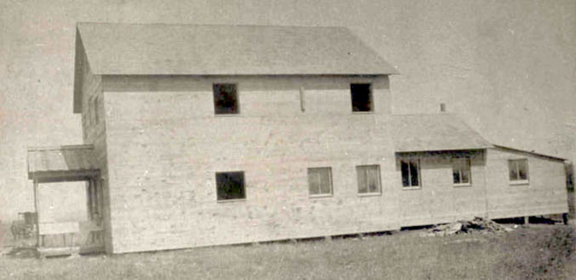

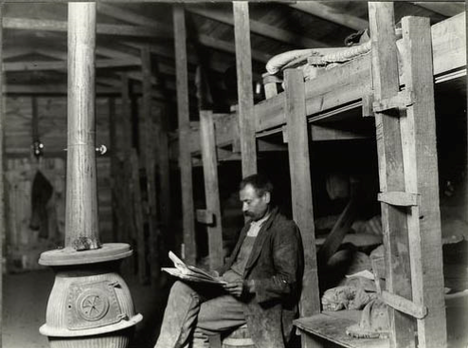

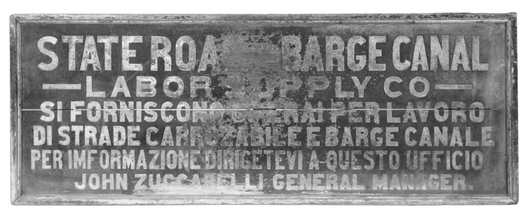

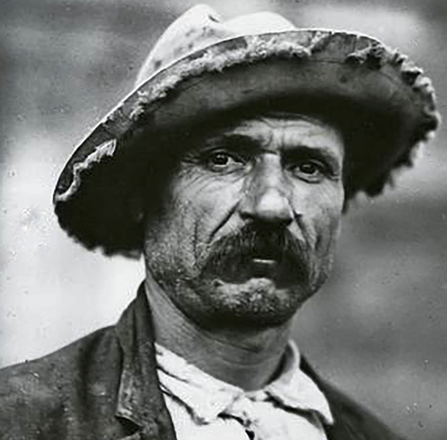

EDITOR’S NOTE: In 2018, the Hudson River Maritime Museum opened the Hudson River and its Canals exhibit to help celebrate the 200th anniversary of the construction of the Erie and Champlain canals between 1817 and 1825. These canal led to far reaching economic and social changes for the areas adjacent to these canals but also for New York City and the Hudson River upon which this system ultimately depended. The Barge Canal system, the backdrop for Paul Schneider’s article, was, completed little more than 100 years ago. Built upon the work of the earlier canals, it was conceived instead on the use of motive power versus animal power. And yet much of the construction still depended upon human labor. Paul Schneider’s article provides important insight into the labor practices and culture surrounding this enormous public works undertaking. On a dreary November day three women and a photographer trudged through rain to examine conditions in a construction labor camp on the state’s barge canal. In one of the unkempt shacks housing workers, they “came upon an Italian who seemed to feel the camp[’s] desolation. He sighed as he said to us: ‘This, America?’” After proudly sharing photographs, pulled from his bunk, of Rome and of his children, “he pointed again to the waste of mud and water [outside]. ‘This, America?’ he said, ‘All for nine dollars a week.’”1 This encounter occurred in 1909. The building of the barge canal system had been underway for four years. An additional nine years would pass before the massive undertaking spanning the state was completed. Now in its 101st year of operation, the New York State Barge Canal System is most easily recognizable by the enormous concrete structures that define it: hulking locks punctuated by gigantic steel gates, immense dams spanning and transforming the Mohawk River, and distinctive powerhouses once generating the electricity to operate each lock and the valves that filled and emptied it. Designated a National Historic Landmark in 2017 as “an embodiment of the Progressive Era emphasis on public works,” the barge canal was further recognized as “a nationally significant work of early twentieth century engineering and construction.”2 In 2015, the American Society of Civil Engineers named the five locks at Waterford, New York as a Historical Civil Engineering Landmark representing “the greatest series of high lift locks in the world … elevating boats through a height of 169 feet."3  As this photograph of a boarding house for workers employed on the Champlain section of the barge canal illustrates, housing conditions varied according to the contractor responsible for a specific phase of work. Although appearing neatly built and a great improvement of over the shacks visited by the investigating committee, it is quite possible that this house was intended for skilled workers rather than unskilled immigrant laborers. Handwritten annotations on the bottom of this image state that the house was taken down after the project was completed. Courtesy of the Mechanicville District Public Library. Largely overlooked in the superlatives emphasizing engineering and construction prowess are the thousands of un-skilled laborers – many of them immigrants – whose back-breaking and often dangerous work made its construction possible. There are no monuments to them. No preserved shacks or reconstructed labor camps to reveal to modern visitors the conditions in which these laborers lived and worked. The four unannounced callers to that unspecified construction camp were making an automobile tour – an arduous undertaking itself in that early era of auto travel – visiting similar camps associated with major governmental construction projects. In addition to the state barge canal system, New York City’s Board of Water Supply was, by damming the Esopus Creek in Ulster County, constructing the immense Ashokan Reservoir, linking it by a 120-mile long aqueduct to deliver an increased supply of water to the city.4 The small group of intrepid travelers included two members of the New York State’s Commission of Immigration, Lillian D. Wald and Frances A. Kellor. They were accompanied by Mary Dreier and photographer Lewis W. Hine. A founder of the Henry Street Settlement House (which celebrated its 125th anniversary in 2018) in New York City, Lillian Wald was forty-two years old. While focusing her dynamic energies in the Lower East Side, she had expanded her advocation for improving the health, education, working and living conditions of the poor and immigrant communities to a state and national level. She invited the then serving Republican governor, Charles Evans Hughes, to Henry Street in 1908 and persuasively made her case regarding the exploitation of immigrants. In response, Governor Hughes appointed both she and Frances A. Kellor to the nine-member commission mandated by the state legislature to "make full inquiry, examination and investigation into the condition, welfare and industrial opportunities of aliens in the State of New York."5 Frances A. Kellor, described as a “hard-driving personality,” was thirty-six, had earned a law degree from Cornell University Law School in 1897, studied the newly emerging fields of sociology and social work at the University of Chicago, where she lived in Jane Addams Hull-House, and then in 1903 moved to New York City and the Henry Street Settlement House, where she concentrated her attention on the “difficulties of immigrants and other minorities in gaining equal treatment and opportunity in U.S. society.”6 Mary Dreier, age thirty-four, was at the time, the president of the New York Women’s Trade Union League. Characterized as “an ally of workers,” she, like Kellor, “believed that reform was best achieved by investigation, analysis, and legislation."7 The fourth member of the group, the photographer Lewis Wickes Hine, was the youngest at thirty-two. Writing of Hine’s work, American photographer, Walter Rosenblum suggests that, “the social turmoil of the Progressive period of American history was the fabric of his vision.” The work camp conditions he saw through his 5 x 7 view camera became part of that vision.8 What the lone Italian laborer sitting in the dismal surroundings of his work camp must have thought when these four suddenly trooped in unannounced is not recorded. Certainly, he must have been surprised by the fact that three of them were women. Wald, in her 1915 book, The House on Henry Street, records the meeting with a bit more detail: In a shack that held three tiers of bunks, occupied alternately by the day and night shifts, with a cook-stove in a little clearing in the middle, we found a homesick man, who chanced not to be on the works, reading a book. When we engaged in conversation with him he pointed contemptuously to the bunks and their dirty coverings, and said, "This America! I show you Rome," and produced from under his bed a photograph of the Coliseum.9  The homesick Italian laborer who Wald, Kellor, Dreier and Hine encountered in a state barge canal work camp in November 1909. Black and white photograph by Lewis Wickes Hine. Courtesy of the New York Public Library, Digital Collections, the Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection. The photograph shown above is of that same “homesick” laborer quoted above. This photograph was one of twenty taken by Hine that graphically illustrated Wald and Kellor’s report on the findings of their investigation published in the January 1910 issue of The Survey. Wald’s criticisms of what she, Kellor, Dreier, and Hine discovered are blunt: [The state] takes great care to prevent the freezing of cement, but permits any kind of houses to be used for its laborers. It is wholly indifferent as to how they are ventilated, lighted, or heated, how many men sleep in them, or whether the sleeping quarters are also used for cooking and eating and the bunks as cupboards. Neither does it care whether the men can keep themselves or their clothes clean.10 Quoting a New York Times article, The Albany Evening Journal of Tuesday, January 4, 1910 noted that the investigators discovered that “the mules were found to be housed in better quarters than the laborers.” Further, the reprinted article stated that, “One entire state camp consists of five buildings. The largest about 50 by 20 feet, contains 52 bunks in a double tier and has a small stove for heating and cooking. The windows are closed tightly and there is one door. This building is set flat upon the side of the canal, upon swampy ground in the midst of mud so deep that on the day of the visit it was necessary to wear rubber boots.”11 Wald and Kellor in their published report articulated their belief that “here in a democracy, in our greatest creative achievements, we can set standards which will make for democracy and not for petty despotism, immorality and physical deterioration. State and city can set standards for life and labor in the construction camps, and see that they are enforced, as easily as they can determine the grade of stone used and the tensile strength of steel.”12 Particularly in the state barge canal camps, however, what they found fell far short of such standards. “With one exception, they found state and city personified, so far as the immigrant workers were concerned, by the padrone whose largest profits are to be drawn from the vice, drunkenness, instability and ignorance of the men …. In state camps they found the padrone in full control, supplying job, bed, board and drink; they found a building with sixty-five cots for a hundred men, another with bunks in the dark cellar; they found state camps wholly dependent upon any spring, well or pump in the neighborhood; they found nuisances committed without restriction, the grounds filthy, and no means for recreation.”13 Who was the “padrone” Wald and Kellor referred to so vehemently? The word had its origins in fourteenth century Italy according to the Oxford English Dictionary. At that time, it referred to the master of a ship. The term came to be associated in the United States with “an exploitative (usually Italian) labor contractor, who employs unskilled Italian immigrants.”14 On the state and city government construction projects that Wald, Kellor, Dreier and Hine were investigating during their auto tour, the padrone acted as the intermediary between the construction contractor and the unskilled laborers that contractor required. This freed the governmental agencies responsible for these massive projects from having to recruit, care for, administer, manage, and supervise the huge temporary workforce needed to turn plans and specifications into physical and monumental reality.  Detail of a Lewis Wickes Hine photograph published with their 1910 investigative report. Its caption read in part: “A Camp Bar. Connecting through a store with the sleeping quarters… The other furnishings consist of tables for card playing and gambling. The ‘commissaire’ (the padrone owner) of this establishment was asked if he needed policemen to keep order. ‘Me the sheriff,’ he said. Courtesy of the New York Public Library, Digital Collection, the Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection. In 1909 the padrone system was already decades old: a proven method of acquiring cheap labor needed to construct dams, railroads, canals, and roads in addition to mining operations of all types throughout the United States.15 It was extremely exploitive of those unskilled workers on whom it depended. John Koren in an 1897 report he wrote for the federal Department of Labor described in detail how it worked. The American contractor, wishing to secure the cheapest possible labor wherewith to carry out some new enterprise, would apply to a resident Italian immigration agent (soon to be dignified by the name ‘banker’) for a stated number of men. The latter, having through subagents in Italy collected as many as required, shipped them across on prepaid tickets, for which he received a stipulated commission. On arrival of these immigrants the agent would make an additional profit by boarding them at exorbitant prices until they could be sent to their destination, the expense being deducted from their prospective wages. The further privilege of supplying them with food and shelter while at work was also commonly granted the agent, and if a banker, he could from time to time add to his profits by charging unreasonable rates for sending the scanty savings of the laborer to Italy. Finally, he had in prospect a commission on the return passage to Italy when the contract expired, for the immigration then as now, was chiefly of a migratory character. Few remained here beyond the time of their contract….16 The lonely Italian laborer encountered by Wald, Kellor, Dreier, and Hine had undoubtedly undergone something very similar to find himself sitting in that work camp shack in November 1909. While Hungarians and immigrants from Slavic countries were also caught up in the clutches of the padrone system, the majority of unskilled laborers came from Italy, specifically from southern Italy. In a report published in 1907 for the federal Bureau of Labor, Frank J. Sheridan included numerous tables of statistical information clearly showing the higher percentage of unskilled laborers immigrating into the United States and especially into New York State were southern Italians. For example, in the span of a year ending in June of 1906, 117,119 immigrants from southern Italy versus just 12,984 from northern Italy came to New York.17 The historic causes that created this late-nineteenth through early-twentieth century geographic wave are far too complex to address in this article. However, Sheridan presents three primary reasons driving “common laborers” to leave their native countries: “(1) primary necessity; (2) to escape compulsory military service and other burdens; (3) to become self-supporting.”18 Another compelling reason was unremitting poverty. Historian Michael La Sorte writes, “by the decade of 1910 Italians in the United States were sending home large sums of money …. for some families back home, this money represented a large portion of their total income.”19 Wald and Kellor echo this in the opening sentence of their 1910 report on the work camps: “Word has gone down the line and across the water that New York state is ‘America’ and that a ‘harvest is on.’ Thousands of alien laborers, writing home or returning to Italy or Austria, have told their countrymen of ‘America’ as they have seen it …”20  Large exterior sign advertising for laborers to work on both state roads and the barge canal. The Auburn Citizen newspaper for Monday, April 25, 1910 ran a notice under the headline, “Work for Italians,” that “John Zuccarelli, the general manager of the Barge Canal Italian Laborers’ Supply Company with headquarters at No. 26 Jefferson Street, has secured the contract from Morris Kantrowits of Albany, N.Y. to furnish 160 men of whom 50 will be set to work at once.” The sign is in the collections of the New York State Museum. Image is provided courtesy of the New York State Museum, Albany, NY. The expectations raised by such words going “down the line,” were often dampened by the reality immigrants found. For not only were the living conditions many were forced to endure terrible, but often their very presence was resented. The construction of the barge canal itself had faced considerable opposition from those who saw it has an enormous expenditure by the state in an outmoded form of transportation. A printed circular advancing opposition arguments was published in May 1903, asserting in part that, “if the policy of the State requires the expenditure of the State’s moneys for the purpose of creating facilities for transporting freight in competition with the existing railroads, why should it not be better for the State to construct a four track railroad from Buffalo to Albany along the present route of the Erie canal?”21 The same circular also pressed home an anti-immigrant labor contention: “if carried through, the enterprise is sure to injure the laboring population now employed to the upmost and to bring … tens of thousands of foreign laborers of the lowest type, who will remain when the work is done a drag on our own civilization and a menace to our native workers.”22 Obviously, the opposition challenges to the barge canal’s construction failed, but criticism remained as the actual work proceeded slowly. The Buffalo Times newspaper for Sunday, August 22, 1909, for example, reported on the findings of a tour of inspection a group of state legislators had just completed. Senator Henry W. Hill of Buffalo was quoted as saying, “we found the work progressing very satisfactorily in most places and the contractors generally entering into the work with enthusiasm.” He also asserted that the “undertaking …. in some respects is more difficult than the building of the Panama Canal, because the New York waterways involve so many more engineering and hydraulic problems.”23 Within such an atmosphere, it seems fair to conclude that both state officials in charge of the work and the contractors hired to implement it were under pressure to pursue construction with as much speed and economy as possible. Tellingly, the 1910 inspection tour by the legislators did not mention the laborers toiling across the state or the conditions under which they lived and worked. Did Lillian Wald or Frances Kellor or Mary Dreier or Lewis Hine – each of whom were well versed in the plight of immigrants coming into New York – tell the lonely Italian laborer they met in that barge canal work camp, that his experience was far from unique? We will never know, unless some written record of their visit eventually is found. His fellow countryman, Napoleone Colajanni, writing in 1909 bitterly observed that “the Americans consider the Italians as unclean, small foreigners who play the accordion, operate fruit stands, sweep the streets, work in the mines or tunnels, on the railroad or as ‘bricklayers.’”24 In fact, far more Italian immigrant laborers were employed on railroad construction in the northern states than on both the city and state construction projects Wald and her party were visiting. The living and working conditions of these workers were similar if not worse in some cases.25 It is from the experiences of those Italians in railroad construction work camps reported by Frank Sheridan that we finally hear the actual voices of some of these men. Sheridan writes that their declarations were given in evidence of the abuses they had undergone while working on railroad construction projects. He also notes that their words “are translations from the statements made in Italian by each of the laborers.”26 Below is just a portion extracted from one such statement. Names and locations were deleted in the original. "During the summer of 1903 I was working on the _________ Railroad in the gang of ______, and was lodged at the shanties conducted by [the padrone] at _________. On account of the unhealthy conditions of the shanties, the rottenness of the groceries sold in the store therein, and the exorbitant prices charged, I couldn’t live there and I quitted work. I had to sleep on a handful of straw [charged 25 cents], pay $1 monthly for rent of the shanty, 25 cents per month for lamp and light, 50 cents monthly for coal, beer 6 cents per bottle, 1 ½-pound loaf of bread 10 cents, macaroni 8 cents per pound, tomatoes 14 cents a can, cheese 36 and 40 cents per pound …. and not only that, but bound to spend at least $10 per month, and with such high prices $10 was not enough to keep a man in shape for work fifteen days. Further, to secure work on the _______Railroad at such conditions, I had to pay to [the padrone] $10 [$5 per time] otherwise he wouldn’t allow me to work.27" Today, we might think such prices remarkably cheap until we are reminded that unskilled Italian laborers were typically charged amounts that “were never less than two to four times the prevailing market prices.”28 So, for example, if a consumer paid $2.35 for a loaf of fresh white bread today in 2019, the immigrant buying that same loaf from the padrone run store in a work camp might be charged anywhere from $4.70 to $9.40. It is small wonder that workers sometimes simply walked away looking for better work and living conditions, sometimes scrimped together enough money to return to Italy, sometimes tenuously managed to establish themselves in the communities near where they worked, and sometimes simply had enough and attacked the padrone or his representatives. Late in April of 1908 this is exactly what happened in Waterford, New York. The Wyoming County Herald ran a story datelined April 29, Troy, which reported that: “a riot occurred among the Italians employed on the barge canal work at Waterford. The padrone who places men at work, it is charged, gets $5 from each man and then if the man does not trade at the supply store conducted by the padrone, that person is discharged, and another is hired. Several hundred Italians descended upon the store and there was a free fight in which clubs and fists were freely used. The Italians prevented all work at the section. Deputy sheriffs were necessary to quell the riot.29" What happened to either the padrone or the rioting laborers is not reported, but it illustrates the sheer frustration and anger that could build-up in the confines of the laborer camps. While not all canal construction workers lived in such camps, they represent what was an indispensable component in the creation of the barge canal system; a massively re-imagined and re-engineered waterway that served the state’s and nation’s urgent needs for the shipment of materials, fuel, and equipment during both World Wars I and II.  Detail of Lewis Wickes Hine famous portrait of an Italian laborer on the NYS Barge Canal. Hine has captured the rough-hewn character, weariness, and dignity of this individual. Courtesy of the New York Public Library, Digital Collection, the Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection. Today’s barge canal is characterized by pleasure boats, kayaks, tour boats, and leisurely piloted rental canal boats carrying visitors eager to experience its beauty and to explore the villages, towns, and cities it connects. Walkers, joggers, and bicyclists ply its banks along paved towpaths, the original need for which was eliminated by the self-powered vessels and towing tugs that replaced horses and mules from the pre-barge canal era. In the reigning tranquility of the canal today, its users hear no echoes of the shouts, groans, cries of pain or anger, laughter, insults, name calling, curt orders, hammers, squeaking wheel barrow wheels, dynamite detonations, shrill whistles and exhaust blasts from steam dredges and locomotives, and the myriad of other sounds that heralded its birth. The physical remains of those flimsy structures composing the work camps where thousands temporarily lived amid those sounds are long gone, but the human lives they barely sheltered are woven into the fabric of the history of the state. 1 Lillan D. Wald and Frances A. Kellor, “The Construction Camps of the People: The Findings of an Automobile Tour of Investigation of Camp Conditions Along the Line of New York State’s New Barge Canal and New York City’s New Aqueduct,” The Survey, January 1, 1910, 460 (hereafter cited as Wald, “Construction Camps”). The Survey was published by the Charity Organization Society of New York City, founded in 1882 and characterized as “one of the most influential philanthropic organizations in New York City.” For this quote see Anne M. Filiaci, “Lowell and the Charity Organization Society of New York,” accessed 30 December 2018, http://www.lillianwald.com/?page_id=216. 2 National Historic Landmark, A National Honor” Erie Canal National Heritage Corridor website, accessed 27 December 2018, https://eriecanalway.org/resources/NHL. 3 “Flight of Five Locks,” ASCE American Society of Civil Engineers, Historic Landmarks, accessed 27 December 2018, https://www.asce.org/project/flight-of-five-locks/. 4 Edward Hagaman Hall, The Catskill Aqueduct and Earlier Water Supplies of the City of New York […] (New York: The Mayor’s Catskill Aqueduct Celebration Committee, 1917), 112. “The length of the aqueduct from Ashokan to this reservoir [Silver Lake Reservoir in Staten Island] is 119 miles, to be exact, but it is called 120 miles in round numbers.” 5 Report of the Commission of Immigration of the State of New York (Albany, NY: J. B. Lyon Company, 1909), 1. For an overview of the history of the Henry Street Settlement House and Lillian D. Wald visit its website at: https://www.henrystreet.org/about/our-history/exhibit-the-house-on-henry-street/ and especially view the short video there “Baptism of Fire – The House on Henry Street.” 6 Allison D. Murdach, “France Kellor and the Americanization Movement,” Social Work 53, no.1 (January 2008): 93. 7 Ann Schofield, "To do & to be": portraits of four women activists, 1893-1986 (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1997), 50, 60. 8 Walter Rosenblum, foreword to America & Lewis Hine: Photographs 1904-1940 (New York: Aperture, 1997), 12, 15. 9 Lillian D. Wald, The House on Henry Street, with a new introduction by Eleanor L. Brilliant, (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 1991). First published 1915 by Henry Holt and Company. 295, (hereafter cited as Wald, House on Henry Street). 10 Wald, House on Henry Street, 296. 11 “Barge Canal Labor,” The Albany Evening Journal (Albany, NY), January 4, 1910. 12 Wald, “Construction Camps,” from the Foreword, unpaginated, following page 448 13 Wald, “Construction Camps,” from the Foreword, unpaginated, following page 448 14 “padrone,” Oxford English Dictionary online, accessed February 9, 2019, http://www.oed.com.dbgateway.nysed.gov/view/Entry/135946?redirectedFrom=padrone#eid. The plural of padrone is padroni. 15 Edwin Fenton asserts that the padrone system dates to the 1840s, while John Koren, writing about it for the Department of Labor in 1897, says its origins “are not easily traced” but seems to have come into prominent use after the Civil War during industrial recovery and growth during “which capital sought labor with almost reckless eagerness.” See Edwin Fenton, Immigrants and Unions, A Case Study: Italians and American Labor, 1870-1920 (New York: Arno Press, 1975), 77, and John Koren, "The Padrone System and Padrone Banks," Bulletin of the Department of Labor 9, March 1897 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1897), 113, hereafter cited as Koren, “The Padrone System.” 16 Koren, “The Padrone System,” 114. 17 Frank J. Sheridan, “Italian, Slavic, and Hungarian Unskilled Immigrant Laborers in the United States,” Bulletin of the Bureau of Labor 72, September 1907 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1907), 409. 18 Sheridan, “Immigrant Laborers,” 406. 19 Michael La Sorte, La Merica: Images of Italian Greenhorn Experience (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1985). 5. 20 Wald, “Construction Camps,” 449. 21 This circular is quoted in Henry Wayland Hill, “An Historical Review of Waterways and Canal Construction in New York State,” Buffalo Historical Society Publications, 12 (Buffalo: Buffalo Historical Society, 1908), 346. 22 Hill, “Historical Review,” 347. 23 “Four Years Yet on Barge Canal, Says H. W. Hill,” The Buffalo Times (Buffalo, NY), August 22, 1909. The Senator Hill quoted in the news article is very likely the same Henry W. Hill who wrote the 1908 article quoted in footnote 21. 24 This quotation is from Napoleone Colajanni, Gli Italiani negli Stati Uniti (Napoli: Rivista Popolare, 1909), 44, translated and cited in La Sorte, La Merica, 61. 25 In a table included with Frank Sheridan’s 1907 report illustrated the numbers and percentages of various immigrant nationalities (dominated by Italians, Slavs, and Hungarians) employed in various occupations in both northern and southern states. In the North fully 75.93 percent of those immigrants engaged in railroad construction and repairs were Italians. Those immigrants in occupations categorized as “canal construction laborers” or “dam and waterworks construction,” were quite small by comparison. Sheridan’s breakdown of occupations may distort his results. For example, “excavating laborers, ditching laborers, and concrete and cement laborers” could all have been employed on either the barge canal or the Ashokan Reservoir projects. Also, his numbers are based on immigrants sent to these occupations by New York Employment Agencies and very likely do not reflect those hired out through the difficult to regulate padrone system. See Sheridan, “Immigrant Laborers,” 420. 26 Sheridan, “Immigrant Laborers,” 445. 27 Sheridan, “Immigrant Laborers,” 447. 28 La Sorte, La Merica, 81. 29 “Riot Among Barge Canal Laborers,” Wyoming County Herald (Arcade, NY), May 01, 1908. AuthorPaul G. Schneider, Jr. is an independent historian and a member of the National Coalition of Independent Scholars. This article was originally published in the 2019 issue of the Pilot Log. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 [email protected] Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |