History Blog

|

|

|

|

|

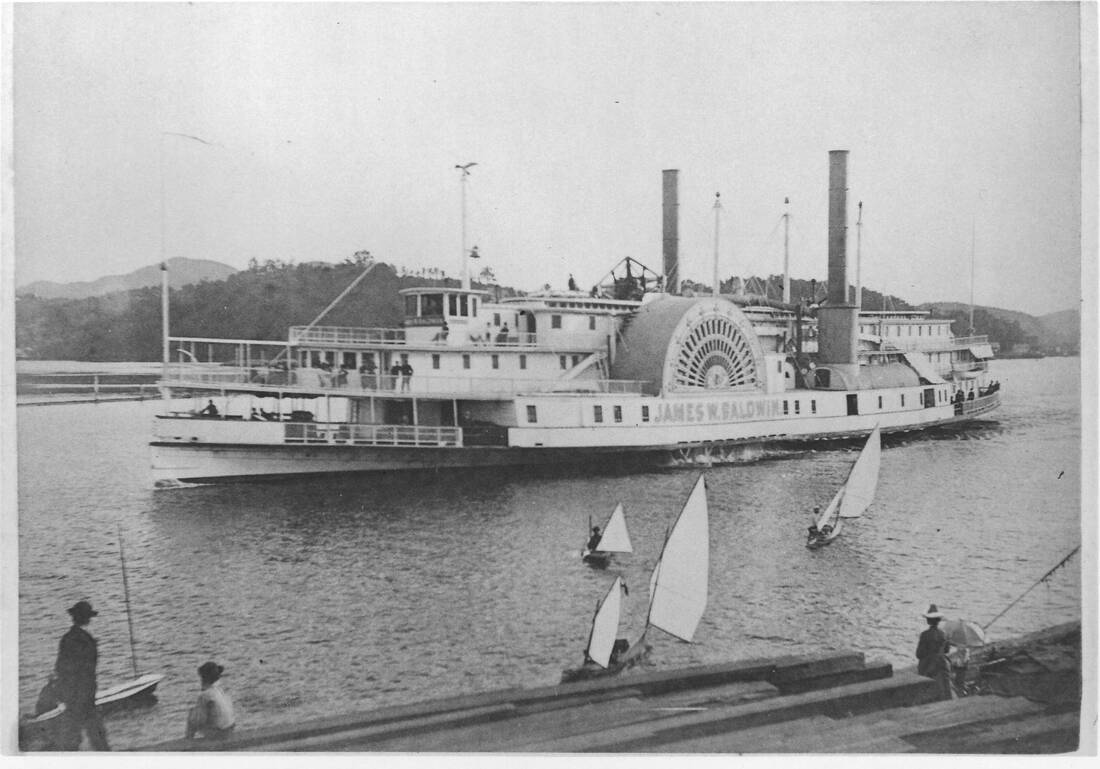

Editor’s Note: The following text is a verbatim transcription of an article featuring stories by Captain William O. Benson (1911-1986). Beginning in 1971, Benson, a retired tugboat captain, reminisced about his 40 years on the Hudson River in a regular column for the Kingston (NY) Freeman’s Sunday Tempo magazine. Captain Benson's articles were compiled and transcribed by HRMM volunteer Carl Mayer. See more of Captain Benson’s articles here. This article was originally published May 7, 1972.  The steamer “James W. Baldwin” was a nightboat out of the Rondout. It was built in 1860 in the same shipyard in New Jersey as the “Mary Powell”. Here, c. 1880s, a group of small sailboats catch the evening breezes on the Rondout as the “Baldwin” heads out to New York City. Donald C. Ringwald Collection, Hudson River Maritime Museum. Within a few years after the introduction of steamboating on the Hudson River, Rondout Creek soon developed into the leading port between New York and Albany. This was due principally to the fact that it was the eastern terminus of the D. & H. Canal. Shipments of Ulster County blue stone. Rosendale cement, lime, the concentration of brickyards along the river north of Kingston, and the natural ice industry also all played major parts in the growth of Rondout harbor. As activity along the creek grew, so did the size of the steamboats serving Rondout. Any steamboat serving Rondout, obviously had to be able to turn around in the creek. The width of the creek, as a result, had some bearing on the design of the steamboat, particularly its length. I suppose this factor also had a direct bearing on the location of the steamboat docks as well as the early growth of Rondout itself. The creek is at its navigable widest just south of where the Freeman Building is now located and this was where the steamboat wharves and docks were located — between the foot of Broadway east to the foot of Hasbrouck Avenue. Steamboats in regular service out of Rondout almost always turned around as soon as they entered the creek, prior to the unloading of passengers and freight. This fact is borne out by old time photographs of steamers berthed at Rondout. Of the many photographs have seen, all but one show the steamboats facing downstream. The sole exception is a photo of the “Mary Powell”, and in this one photograph only she lies head up. Rondout’s Largest For years, the largest steamboat sailing out of Rondout Creek was the “Thomas Cornell,” built in 1863 and 310 feet long. Other larger steamboats out of Rondout were the famous “Mary Powell” at 288 feet, the “James W. Baldwin” at 275, and the “Benjamin B. Odell” at 264. The longest one of all to sail regularly out of Rondout was the Day Liner “Albany,” 326 feet long, which replaced the “Mary Powell” on the Rondout to New York run during the season of 1914 through 1917. I, have been told the “Albany,” on occasion, used to use the steam yacht “C. A. Schults” — that once ran between Rondout and Eddyville — to help pull her bow around. All of the, others turned unassisted. For many years, Ben Johnston owned a drug store on East Strand. Johnston told me when the “Benjamin B. Odell” turned around in the creek, at times the vibrations set up by her turning propeller would shake bottles off the shelves in his drug store. This was due to the fact that all the land along the Strand was filled-in land. It is my understanding that the area all along the Strand was once a dandy beach — and the old sloop and schooner captains would beach, or strand, their vessels on this beach at high tide. Then, when the tide went out, they would make bottom repairs or caulk under-water leaking seams on their boats exposed by the drop in tide. When the tide came back in, they would float their sloops and schooners. I have been told this act of stranding their vessels on this beach is what gave the Strand its name when the area was filled in and the beach was developed into a street.  The small passenger steamer, “C.A. Schultz”, was one of a group of boats operating on the Rondout Creek, 1880s to 1920. She would leave from Rondout and stop at hamlets like Wilbur, Eddyville and South Rondout. This was certainly a pleasant way to travel from one hamlet to another. Donald C. Ringwald Collection, Hudson River Maritime Museum An old boatman also once told me about an incident that took place when the “Benjamin B. Odell” was turning around off her Rondout wharf. Normally, she would come along-side the dock, can her bow out from the dock and put a stern line from the port quarter out to a bollard on the dock. Then, she would go ahead slow and swing around like a slowly moving giant pendulum. Captain George Greenwood would be up on the bridge and the mate down on the main deck in charge of the deckhands tending the lines. On this particular day, just as the “Odell” got broadside in the creek, the stern line snapped. The mate had a police whistle and blew a series of toots on it to let the captain know the line had snapped. Before the mate could get another line out, the “Odell” started to move across the creek. Except for stopping the engine, Captain Greenwood gave no indication anything was wrong. The mate in the excitement didn’t notice the engine had stopped and continued to blow his police whistle. After several series of excited toots and getting no response from the captain, the mate bounded up the companionways at the stern of the “Odell” to the top deck. There, Captain Greenwood stood calmly on the bridge watching the slowly approaching south shore of the creek. Captain Greenwood let the “Odell’s” bow slowly drift right onto the creek’s south shore and the incoming tide carry her stern up stream. When the angle was right, Captain Greenwood backed down, put the “Odell’s” port quarter close to the Rondout dock, got out a spring line, went slowly ahead and brought his steamer alongside the dock so perfectly he wouldn’t have broken an egg had one been between the steamboat and the dock. The old time captains, like Captain Greenwood, were superb ship handlers. They knew exactly what their steamboats would do in any combination of wind and tide. They were true masters of their trade, made the difficult look easy, and rarely got the recognition they deserved. It seems the only time anyone took notice of them was in the rare event something went wrong. And, then, it was often due to something over which they had little control, such as a mechanical failure, rarely an error in judgment. AuthorCaptain William Odell Benson was a life-long resident of Sleightsburgh, N.Y., where he was born on March 17, 1911, the son of the late Albert and Ida Olson Benson. He served as captain of Callanan Company tugs including Peter Callanan, and Callanan No. 1 and was an early member of the Hudson River Maritime Museum. He retained, and shared, lifelong memories of incidents and anecdotes along the Hudson River. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support more history blog content, please make a donation to the Hudson River Maritime Museum or become a member today!

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorThis blog is written by Hudson River Maritime Museum staff, volunteers and guest contributors. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

Hudson River Maritime Museum

50 Rondout Landing Kingston, NY 12401 845-338-0071 [email protected] Contact Us |

GET INVOLVED |

stay connected |